Research Article

Research Article

15-Minute City: Echoes of 1960s Suburbia

Vaattovaara Mari* and Joutsiniemi Anssi

Department of Geosciences and Geography, Professor of Urban Geography, Director of the Institute of Urban and Regional Studies, Finland

Vaattovaara Mari, Department of Geosciences and Geography, Professor of Urban Geography, Director of the Institute of Urban and Regional Studies, Finland

Received Date:November, 13, 2023; Published Date:January 11, 2024

Abstract

This study offers a critical examination of the 15-minute city concept within the Helsinki metropolitan area, juxtaposing the theoretical ideals of compact, local living with the practical realities of urban development. Drawing from three recent projects and national studies, it scrutinizes the evolution of Helsinki’s high-rise suburbs built in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as contemporary planning documents. Despite the popularity of the 15-minute city model as a strategy for ecological and social sustainability, the findings reveal a significant gap between the promoted ideals and actual urban development. The analysis underscores a continued reliance on old planning concepts under new guises, questioning the efficacy of current practices in achieving genuine change.

Additionally, the study explores the role of real estate investors, developers, and urban planners in sustaining these utopian visions, underscoring the need for empirical evidence and post-occupancy evaluations. It points out the similarity between the ideals of 1960s compact development and the modern 15-minute city model, yet it observes a pronounced lack of substantive change in actual planning practices. Moreover, the paper discusses the impact of political rhetoric and conceptual ambiguity in shaping urban policy, arguing that the 15-minute city concept has become a platform for oversimplified ecological goals and densification strategies that fail to address socio-economic disparities or genuinely enhance local living conditions.

The authors call for a recalibration of urban planning, underscoring the importance of harmonizing national policies with local community involvement, and critically assessing the 15-minute city model’s potential to foster disconnected urban enclaves.

Keywords:15-Minute City; Urban Planning; Helsinki Metropolitan Area; Sustainable Development; High-Rise Suburbs; Urban Density; Segregation; Social Sustainability; Ecological Goals

Introduction

The concept of local living in rapidly expanding urban areas originated with the creation of the neighborhood unit in the early 1900s. Furthermore, the construction of high-rise concrete suburbs globally during the 1960s and 1970s was based on similar principles of a compact city, where services are located nearby, thereby reducing the necessity for extensive travel. This “urban ideal,” which has manifested in various forms over the last decade, also carries the promise of preserving nature and enhancing local living qualities. The most recent iteration of this local living ideal is embodied in the concept of a ‘15-minute city’ and its underlying principles (Moreno et al. [1,2]). The circulated concept (see, for example, Kissfazekas [3], Norvasuo [4], Pozoukidou & Chatziyiannaki [5], Lu & Diab [6]) is can be seen as an attempt to modify old theories of accessibility and catchment areas. It also focuses on local quality and increased construction, representing a trend that has been ongoing for some time. As Moreno et al. [2] express, “It is then a matter of bringing the resident’s demand closer to the offer that is proposed to them, ensuring functional mixing by developing social, economic, and cultural interactions, and ensuring a significant densification…” . In further developing the 15-minute city model, it is anticipated that this will improve residents’ neighborhood quality and “maximize their local public spaces, green spaces, and other public infrastructures.” (Moreno [1]).

Moreno et al.’s concept draws on principles that have been explored in economic and transportation geography since World War II, including studies of catchment areas and gravitation modeling tradition (see, for example, Lösch [7], Hoover [8] Isard [9]). However, the distinctive feature of the 15-minute city model is the assumption that these varying spatial interactions can be scaled down in favor of hyper-local spatial interaction, incorporating a clearly articulated sustainable mode of transport. The assumptions include several significant uncertainties related to both the nature of catchment areas for various activities/amenities and the actual behavior of economic agents: residents, shopkeepers, and other stakeholders in the planning process.

These uncertainties translate into three critical challenges in applying the model to planning practice. Firstly, as an operational planning model, it requires normative judgment about what amenities should be included within this 15-minute catchment area. Secondly, the area within a 15-minute catchment in any metropolitan area is too diverse and broad to be prescriptive in any practical sense. There are evidently more central and more peripheral areas that are perceived differently from location to location. This leads to a third difficulty: the model does not anticipate how people ultimately make decisions in a broader accessibility landscape - how they allocate their time between local and non-local activities, how they develop their businesses and provide services, or how decisions at the detailed planning level balance public and private neighborhood interests.

Ecologically, the model tends to overemphasize the benefits derived from changes in transportation and density while sidelining several recently recognized issues related to social and economic sustainability, the carbon emissions of construction, and disturbances in natural processes at both local and planetary levels. It is even suggested that the lack of rigor and loose conceptualization only encourages physical determinism instead of true measures to meet the initial targets. (Pozoukidou & Chatziyiannaki [5]) Additionally, this reinvented concept of hyper-local living, the 15-minute city, has faced criticism for potentially contributing to segregation and gentrification, rather than delivering the promised benefits of better health and a more sustainable city. As Edward Glaeser [2021] wrote: “Cities should be machines for connecting humans – rich and poor, black and white, young and old. Otherwise, they fail in their most basic mission and they fail to be places of opportunity.”

Despite its potentially problematic implications, which include altering the classical theoretical framework of accessibility and challenging the logic of multiple catchment areas, the 15-minute city concept has garnered significant enthusiasm. Multiple actors are keen to have stakes in the planning and construction of the “new 15-minute city”. Not surprisingly, the real estate business is excited (Kostiainen [10-12]; NREP [13]). As Catella [14], one of the leading property investment management companies in Europe, presents:

“Anyone following the evolution of this development should be reassured, because a new movement is finding more and more supporters across Europe: the ‘15-Minute City’. Cities, municipalities, project developers, and the bicycle faction find their pleasure in it. … by bike or walking, the essential retail infrastructure, doctors, local recreation, education, and gastronomy/culture can then ideally be found. The aim is to focus on decentralized services …And to develop pedestrian, bicycle, and traffic-friendly routing within the city quarters”.

Not only representatives of real estate and construction companies but also many planners have embraced the imaginaries promised by the concept, and it is now also in Finland being incorporated into official planning documents (City of Helsinki [15], City of Espoo [16]). In Helsinki, for instance, one of the very new plans was advertised to be planned further ahead by using these principles (Helsingin Sanomat). Thus, it is important to explore the assumptions, possibilities, and planning principles embedded in the idea of living locally in a 15-minute city.

Materials and Methods

This paper derives its analysis from the study of urban development in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. The results presented stem from three distinct projects completed in the past year, aimed at understanding both policy objectives and actual urban developments. Both authors have decades of experience analyzing the development of the HMA. The perspectives of our doctoral dissertations on social and spatial differentiation of the Helsinki metropolitan area (Vaattovaara [17]) and spatio-temporal accessibility analysis (Joutsiniemi [18]) have informed our analysis of the patterns and directions of change in the city region. In this article, we reference three recently completed studies: a study on the development of Finnish high-rise suburbs (Vaattovaara et al. [19]), one on alternatives to pathologically developed construction sectors (Vaattovaara et al. [20]), and a post-occupation study (Vaattovaara & Vuori [21]). Additionally, our conclusions draw upon three national-level studies in urban and planning policy (Vaattovaara et al. [22], Häkkänen et al. [20], Joutsiniemi et al. [23]). Conducted in Finnish, these recent studies and this summary may hold value for similar comparative research.

Results and Discussion

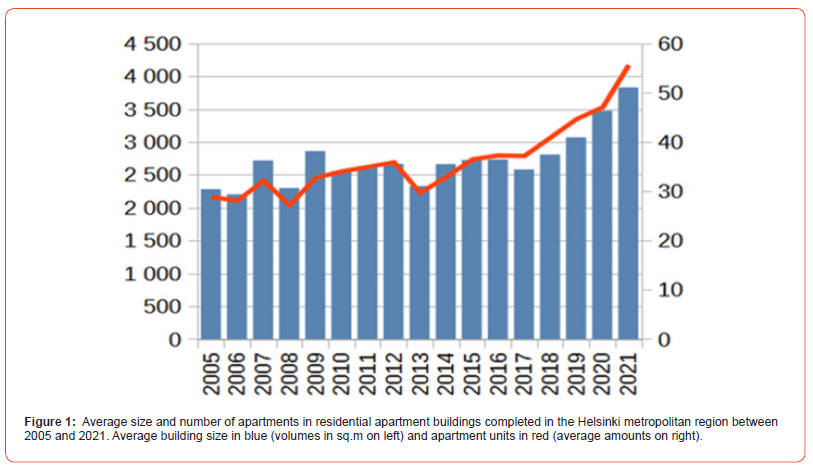

Our initial observation highlights a rapid increase in the size of individual buildings. During the 1990-2000 period, the average size of an apartment building was 2500 sq.m., which has now doubled. Similarly, the number of apartments in a building has increased from approximately 30 to nearly 60, with some buildings in these locations now housing over 120 apartments. Despite the increase in building scale, the size and quality of apartments are decreasing (Pelsmakers et al. [2012], Vaattovaara & Vuori [21]). The assumption that densification leads to improved outcomes is, in fact, misleading (Figure 1)..

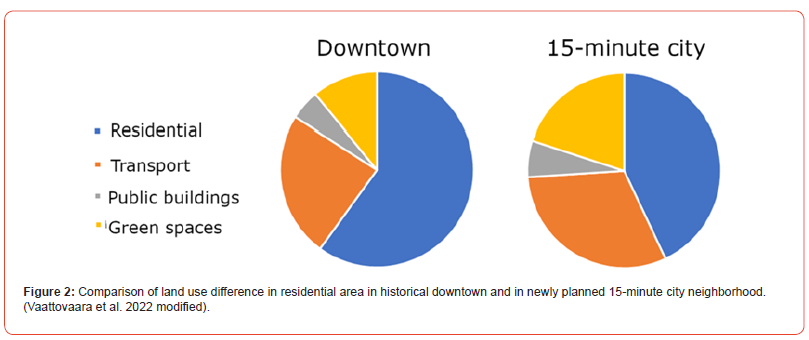

Contrary to expectations, the adoption of sustainable modes of transport hasn’t notably altered the fundamental land use patterns. The second research observation indicates an increase in land use for transportation: the width of right-of-way reserves in urban area has approximately doubled in 70 years. Despite intentions to build dense, walkable urban areas with nearby services, the result is often the opposite. Our analysis of the recently approved 15-minute city development plan in Kera, Espoo, reveals less land used for housing, with a greater area allocated for traffic (Vaattovaara et al. [24]). In Figure 2, the land use shares of different land uses are compared to downtown neighborhoods. At first glance, it appears that the amount of green space has increased, but further analysis shows this is due to categorizing several leftover spaces as parks (ibid., 29-32). Thus, the promise of improved public spaces and infrastructure is not evident in realized plans.

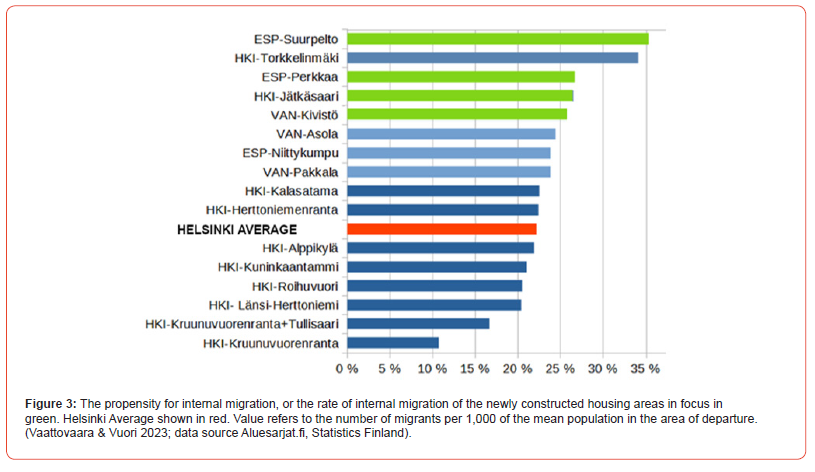

The third point of discussion addresses the social dynamics in the newly constructed housing areas within the Helsinki metropolitan area. The rapid turnover of population, as measured by internal migration rates in these outlying areas, disconnected from the existing urban structure, poses a risk of unrest, selective migration, and rapid segregation (Figure 3). Unlike the urban core, exemplified by the HKI-Torkkelinmäki area, these new housing developments are becoming increasingly vulnerable. Our research shows that these areas are already skewing towards immigrant-dense housing, diverging from the ideal socio-economic balance, suggesting the need to re-evaluate the planning concept (Vaattovaara & Vuori [21]).

Lastly, our fourth observation concerns services: there appears to be no correlation between urban amenities and the densified neighborhoods in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area (HMA). We tracked the development trend over several decades, noting that shopping centers continue to cluster outside these localized areas. The services are not evenly spread across the HMA or adjacent to new major housing developments, but are concentrated in areas with the highest accessibility decile within a 3-8 km radius. It also shows a negative correlation between locations of optimal local network accessibility and residential density, contradicting the local scale ideal promoted by the 15-minute city concept (Vaattovaara et al. [19], 59-66). Therefore, the idealized and promoted features such as “essential retail infrastructure, doctors, local recreation, education, and gastronomy/culture” are not obviously present in the densified areas either.

Conclusion

Our empirical analysis, focusing on the development of highrise suburbs from the 1960s and 1970s as well as recent detailed planning documents, reveals a significant discrepancy between the promoted ideal of a compact city and local living and the actual urban development. The endorsement of these recycled utopian visions by real estate investors, developers, and urban planners should be critically examined through empirical evidence and post-occupancy evaluations. The risk of repackaging old concepts in new attire is substantial.

The urgency to respond to global climate challenges is immense. While the 15-minute city approach isn’t entirely novel, it suggests a shift based on same assumption as earlier theories. However, the the institutional baggage of various stakeholders appear to uncritically seek new justifications for existing practices. Implementing this novel 15-minute city concept would require at least 1) defining and measuring proximity to key urban amenities explicitly, 2) understanding the existing location choices of different services and 3) emphasize the needs of residents and other stakeholders over the path dependency of formal decision-making. Since there is a striking similarity between the 1960s compact development ideals and this new model, any actual changes in planning practices are hard to discern.

In our report for the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland, we highlight the shift in the discourse surrounding urban planning. Recent political rhetoric, hollow concepts, and superficial development narratives illustrate how a prevalent contemporary aspect of Western culture - namely, the practice of bullshitting - is infiltrating urban policy. Philosopher Harry G. Frankfurt differentiates bullshitting from outright lying, describing it as closer to bluffing and nonsense. Modern bullshitting thrives on creating illusions, seizing initiative, and overwhelming opposition with finesse and captivating wordplay. The bullshitter capitalizes on conceptual ambiguity and an ideology-poor environment to further their own goals (Häkkänen et al. [20], Frankfurt [25-29]).

The 15-minute city concept provides a loosely defined and uncritically accepted basis for a new urban development model, primarily fixated on an oversimplified assumption about achieving ecological goals. In Finnish urban development, efforts to increase density have not effectively realized ecological or social sustainability. This approach has inadvertently contributed to socio-economic disparities and a potential rise in societal stratification. The change in suburb populations and service structures align poorly, especially when viewed from the perspective of traditional welfare state ethos. A recalibration of urban planning is necessary, advocating for a synergy of national policy and local community engagement to improve living conditions. Additionally, the 15-minute city concept is critically assessed for its risk of fostering urban enclaves, deviating from the essential urban function of connecting diverse communities. This aligns with Edward Glaeser’s critique of the concept’s potential to compromise the fundamental inclusivity and connectivity of urban environments.

References

- Moreno C, Allam Z, Chabaud D, Gall C, Pratlong F (2021). Introducing the ‘15-Minute City’: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 4(1): 93-111.

- Moreno C (2016) La ville du quart d'heure: pour un nouveau chrono-urbanisme [The 15-minute city: for a new chrono-urbanism]. La Tribune.

- Kissfazekas K (2022) Circle of paradigms? Or ‘15-minute’ neighbourhoods from the 1950s. Cities, 123.

- Norvasuo M (2021) Lähiöiden uudistaminen ja viidentoista minuutin kaupunki [Renovation of suburbs and the fifteen-minute city].

- Pozoukidou G, Chatziyiannaki Z (2021) 15-Minute City: Decomposing the New Urban Planning Eutopia. Sustainability 13(2): 928.

- Lu M, Diab E (2023) Understanding the determinants of x-minute city policies: A review of the North American and Australian cities’ planning documents. Journal of Urban Mobility 3.

- Lösch A (1967) The Economics of Location. John Wiley & Sons.

- Hoover EM (1963) The Location of Economic Activity. McGraw-Hill.

- Isard W (1960) Methods of Regional Analysis: An Introduction to Regional Science. MIT Press.

- Kostiainen J (2023) 15 minuutin kaupunki -konsepti auttaa jäsentämään yhdyskuntasuunnittelua [15-minute city concept helps to structure urban planning].

- Kostiainen J (2020a) Mitä koronan jälkeen – paluu Nurmijärvelle vai 15 minuutin tiiviiseen kaupunkiin? [What after the corona - return to Nurmijärvi or a dense 15-minute city?].

- Kostiainen J (2020b) Palvelut 15 minuutin kaupungissa [Services in a 15-minute city].

- NREP (2022) Nrep yhteistyöhön maailmanlaajuisen C40-pormestariverkoston kanssa – tavoitteena luoda pilotteja 15 minuutin kaupungeista [Nrep in collaboration with the global C40 mayors' network - aiming to create pilots of 15-minute cities].

- Catella (2021) Catella Infographic: The 15-Minute City.

- City of Helsinki (2023) Keski-Viikin kaavarunko [Planning framework of Central Viikki]

- City of Espoo (2022) Kalajärvelle suunnitellaan vartin kaupunkikylää [15-minute city is to be planned to Kalajärvi, Espoo].

- Vaattovaara M (1998) Pääkaupunkiseudun sosiaalinen erilaistuminen: Ympäristö ja alueellisuus [Social differentiation in the capital region: Environment and regionality]. Helsingin kaupungin tietokeskus.

- Joutsiniemi A (2010) Becoming Metapolis. Tampere University of Technology.

- Vaattovaara M, Joutsiniemi A, Bernelius V, Page M, Rönnberg O, et al. (2023) Re: Urbia - Lähiöiden segregaatiohaaste ja tulevaisuus.

- Häkkänen M, Joutsiniemi A, Seuri O, Vaattovaara M (2022) Kaupunkipolitiikan uusi alku? Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland.

- Vaattovaara M, Vuori P (2023) Asuntorakentamisen muutokset pääkaupunkiseudulla ja Tampereella vuosina 2015–2021.

- Vaattovaara MK, Joutsiniemi A, Airaksinen J, Wilenius M (2021) Kaupunki politiikassa: Yhteiskunta, ihminen ja ihana kaupunki [City in politics: Society, human and wonderful city]. Vastapaino.

- Joutsiniemi A, Vaattovaara, MK, Airaksinen J (2021). Empowered by planning law: Unintended outcomes in the Helsinki region. Buildings & Cities 2(1): 837-855.

- Pelsmakers S, Saarimaa S, Vaattovaara M (2022) Avoiding Macro Mistakes: Analysis of Micro-Homes in Finland Today.

- Frankfurt H (2005) On Bullshit. Princeton University Press.

- Glaeser E (2023). The 15-minute city is a dead end-cities must be places of opportunity for everyone.

- Helsingin Sanomat (2023). Viikkiin suunnitellaan asuntoja 7 000 ihmiselle, tavoitteena ‘15 minuutin kaupunki’ [Housing for 7,000 people planned in Viikki, aiming for '15-minute city'].

- O’Sullivan, F. (2021). Where the ‘15-Minute City’ falls short.

- Vaattovaara M, Joutsiniemi A, Jama T (2022) Pientalot kaupungissa – Asuntopolitiikan ja kaavoituksen käyttämätön resurssi [Prefabricated detached houses in the city - The unused resource of housing policy and planning]. University of Helsinki.

-

Golam Rabbani*, Anindita Hridita, Johayer Mahtab Khan and Khandker Tarin Tahsin. Exploring Climatic Hazards and Adaptation Responses to Address Problems of Climate Migrants in Selected Urban Areas in Bangladesh. Online J Ecol Environ Sci. 1(4): 2023. OJEES. MS.ID.000518.

-

Climate migrants, Vulnerabilities, Adaptation, CBF, Bangladesh, Population movement, Climatic hazards, Urban areas, Storms, Cyclones, Floods, Natural disasters`

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.