Case Report

Case Report

A Review on Removable Partial Dentures

Edgardo Pineda Taladriz1, Loreto Canto Contreras2, Verónica Palacios3, Diego Ramírez Villalobos4 and Sebastián Lazo Ruedlinger1

1Maxilofacial Surgery Resident, Universidad del Desarrollo, chile

2Maxilofacial Surgeon, Complejo Hospitalario Dr. Sotero del Rio, Puente Alto, Santiago, Chile

3Maxilofacial & Oral Pathologist, Complejo Hospitalario Dr. Sotero del Rio, Puente Alto, Santiago, Chile

4Maxilofacial Surgery Resident UEA Complejo Hospitalario Dr. Sotero del Rio, Puente Alto, Santiago, Chile

Diego Ramírez Villalobos, Complejo Hospitalario Dr. Sotero del Rio, Puente Alto, Santiago, Chile.

Received Date: April 26, 2024; Published Date: June 13, 2024

Abstract

Vascular malformations are injuries derived from blood and lymphatic vessels that presents heterogeneous variety of symptoms, and imaging and histological characteristics, resulting in differential diagnostics and varied treatments. In order to correctly diagnose these lesions, it is recommended to do complementary exams such as Doppler echography, flux study, computerized tomography, and magnetic resonance. We present the case of a 29 year old patient with an increased submental volume, whose initial physical and imaging examination suggested an epidermoid cyst. After lesion resection and further histological study, the latter showed it consisted of a vascular malformation and not an epidermoid cyst. Here we discuss the importance of complementary imaging examinations to more precisely and differentially diagnose these lesions.

Keywords: Vascular malformations; Venous malformations; Epidermoid cyst; Submental region

Introduction

Vascular injuries affect lymph and blood vessels, among which are 2 large groups: vascular malformations and neoplasia. These anomalies involve a vast diversity of entities that can commit several parts of the body [1, 2].

The etiology of these anomalies is vast and complex, having some theories described as dependent on the entity kind. That’s how tissue hypoxia factor, placenta blood vessel vascularangiogenesis may be involved, which has been previously studied in child hemangiomas [3].

It is of utmost importance to know the classification and clinical characteristics of these vascular anomalies because it enables proper patient treatment [1]. Vascular malformations are characterized by a normal endothelial renewal and growth proportional to the individual, without spontaneous regression [1, 4, 5]. These malformations can also be histologically subclassified according to the predominant blood vessel: capillaries, arteries, lymphatic or mixed [1, 2, 4, 5]; therefore, vascular malformations are classified as capillary, arterial-venous, venous, lymphatic, or mixed [1, 6-8].

The diagnosis of these anomalies is basically clinical, but complementary exams play a fundamental role in their study, classification, and differential diagnosis. Crucial for the latter are imaging studies, which gives us information on the malformation size, activity, flux, and relationship with adjacent tissues, enabling to evaluate the response to procedures [1, 6].

To handle these anomalies, it is not only necessary to have an accurate diagnosis, but also the involvement of a multidisciplinary team [6]. There are different treatments, which will depend on the vascular anomaly type. Among these treatments are surgical resolution and non-surgical (conservative) treatments, such as cryotherapy, laser, sclerosing agents, corticoids, and embolization [1, 6].

Here we show a clinical case of vascular malformation disguised as an epidermoid cyst (EC) in the submental region.

Patient Clinical Background

In this manuscript we present a case of a 29 years-old female with morbid type 2 diabetes mellitus under control with 850mg/ day metformin and previous cesarean section without further complications. She Assisted to the Complejo Asistencial Dr. Sótero Del Río Emergency room to evaluate a volume increase in the submental zone with a 3-year evolution. Patient indicated that it was initially of a “small” size, but that during the last year the volume had increased, and exacerbated disconformities.

Physical examination showed a well-delimited increase in volume in the submental region that extended up to the beginning of the bilateral submandibular region. It had a firm-soft consistency, almost non-displaceable, painful upon local pressure as related by the patient, of approximately 5x7cm (about 2.76 in), with neither skin commitment nor regional adenopathy.

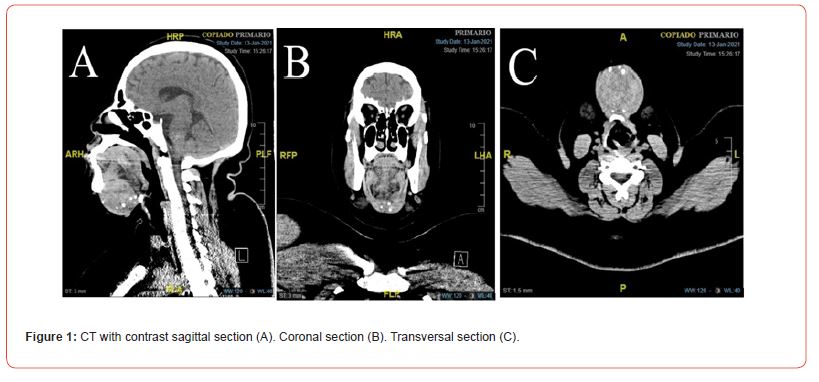

A Computed tomography (CT) of the submental region showed, between the digastric muscles, a well-delimited mass of 4.8 x 4.7 x 3.9 cm (about 1.54 in) in anteroposterior, transverse and longitudinal length respectively. It was predominantly dense, with some patched round areas of less density, and presented multiple thick and round calcifications of up to 5mm (about 0.2 in) inside. The mass was in contact with the submental muscles generating a volume increase that lightly displaced the region tissues (Figure 1).

With the compiled information, clinical record, physical examination and imaging study, the diagnosis was hypothesized as an epidermoid cyst (EC). It was decided to do a full excision of the lesion through cutaneous access.

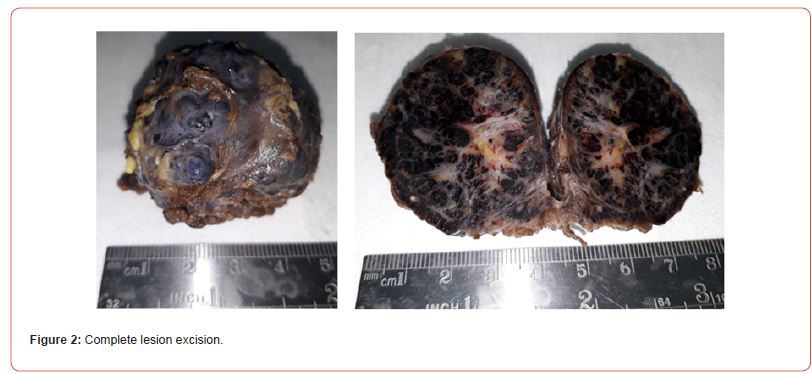

Under general anesthesia, a horizontal submental cutaneous incision was performed over the lesion, followed by a careful detachment identifying vascular structures and preserving them to the muscle plane, followed by full exision following the cleavage plane (Figure 2). Strict hemostasis was controlled, noble elements checked indemnity followed by stitching, the surgery ended without complications.

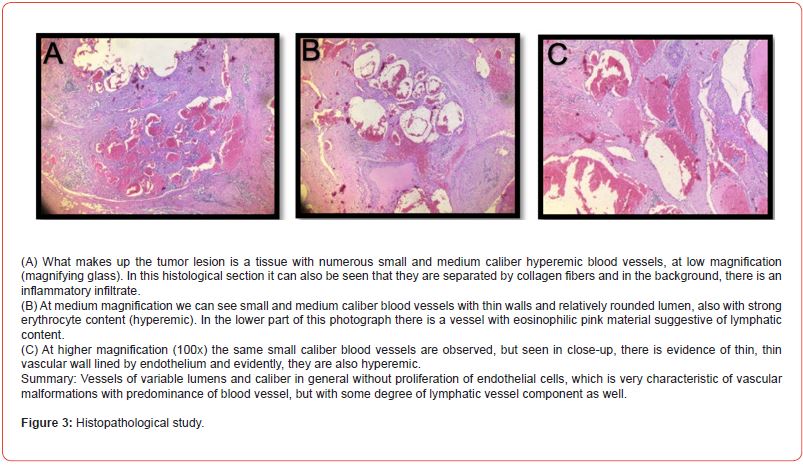

A macroscopic histopathologic study showed white tissue tumor formation, with a round-oval shape of 5 cm (about 1.97 in) major axis, blackish surface, with 3-4mm (about 0.16 in) small round nodules on the surface, like small buddings. Upon cut its solid, dark brown, with partitions and a white reticular organization. Microscopic analysis showed well-delimited tumor formation, constituted by numerous small and medium caliber hyperemic blood vessels, all of them thin walled and separated forming lobes. Between the blood vessels there was striated muscle tissue, dissected by these vessels. Some of these blood vessels had clear eosinophil content, clearly suggesting they were lymph vessels. Therefore, the definitive diagnosis, given the histopathological findings, corresponds to a mixed vascular malformation with a cavernous predominance (Figure 3).

Discussion

Vascular anomalies are lesions of a wide clinical spectrum of two large groups: vascular neoplasia and vascular malformation. These lesions derive from blood or lymph vessels, occasionally showing symptoms, varied imaging and histologic characteristics, increasing their diagnose and treatment complexity [6, 7]. The physical exams of vascular anomalies are crucial: it enables us to determine the characteristics of the lesion, such as its size, localization, evolution, appearance, and its proximity and relation with neighboring structures. Depending on such characteristics it is possible to determine the most appropriate imaging exams [1, 6, 7-10].

Venous malformations are benign lesions secondary to a defective vascular development, formed by venous channels with capillary bed and normal arteries. These are often congenital lesions, do not spontaneously involute as hemangiomas do, and progressively develop with age. They are the most common among vascular lesions, taking about 2/3 of cases. Approximately 40% of these lesions develop on head and neck regions, and are not genderassociated [6, 8, 11-13].

Lymphatic malformations are the second most common among venous malformations [6, 11]. These are congenital lesions, approximately 65% of these are diagnosed at birth and 90% before 2 years old. 90% of them localize on head and neck and do not present involution phases [6, 11]. Lymphatic malformations are secondary to defects on lymphatic vessels morphogenesis, are of variable aspect and may present channels or multiple cystic spaces separated by a fibrous septum, where the walls are made of a single flat layer endothelia and may be surrounded by irregular thickened smooth muscle [6, 11].

Among the most used traditional treatments are surgical resection, sclerotherapy and embolization [6, 8]. In some cases these malformations may be large, infiltrate adjacent tissues, and require multimodal treatments, combining the conservative endovascular (sclerotherapy or embolization) and surgical, obtaining better results, as it reduces risks and complications associated to surgical interventions alone [13]. Surgical interventions are considered adequate when there is spontaneous pain, mechanical allodynia, or when the lesion starts building a malformation due to its extension [6, 12].

recommended Doppler echography, CT and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). CT and NMR are powerful tools to establish the type of vascular malformation, and offers excellent definition to determine the lesion size, detect non-visible components and the lesions involvement with neighboring anatomic structures. Doppler echography is a non-invasive, innocuous, accessible, lowcost and useful tool for hard-to-handle patients, as it provides hemodynamic anatomic information, thus information about blood flow speed and direction, enabling to confirm if the lesion is high-flux (arteriovenous) or low-flux (venous) [1, 6, 11]. In this case, only CT was used as complementary exam to evaluate size, spatial location and the involvement with neighboring anatomic structures of the lesion. Doppler echography was not ordered as previously described clinical and imaging characteristics indicated it corresponded to an epidermoid cyst (EC).

In this case the vascular malformation emulated an EC because of its clinical and imaging characteristics, and its location. The epidemiology of EC indicates that they can appear at any age, commonly in young adults, but rarely on younger people (between 1st and 3rd decades) [14, 15]. The prevalence of the EC on head and neck is between 1,6% to 6,9%, with a prevalence that goes from higher to lower under the tongue, tongue, lips and oral mucous membrane [14].

Among the clinical characteristics of the lesion in the patient, an increase in the volume of the submental region was observed after 3 years, of slow and progressive evolution, with a firmsoft consistency, without committing the skin or any regional adenopathy. That matches the clinical description by Romero F, et al. [16], who describes an EC as an asymptomatic increase in volume, of slow and progressive growth, fluctuating consistency (doughy consistency), and well encapsulated [16]. On the other hand, when the EC appears in the submandibular zone it may show different clinical manifestations, which will depend on its location relative to mylohyoid muscle. If it grows on top of the muscle, the volume increase in the oral cavity may induce dysphagia, dyspnea and dysphony since it pushes the tongue upwards or backwards, and its extension down towards the mylohyoid muscle may produce a double chin appearance [15-17].

The CT imaging study of the lesion showed the presence of a well-defined mass in the submental region, between de digastric muscle, predominantly dense with round less dense patched areas, the presence of several round thick calcifications, which coincides to what was described by Gómez K, et al. [18] relative to de CT study, where a RC is observed as a well-defined and encapsulated structure, with a heterogeneous density, which may present calcifications within [18].

Because of the previous background and the EC diagnostic, it was decided to surgically intervene through a submenta cutaneous access, proceeding to the full exision of the lesion following the adequate cleavage plane. This was chosen because of the initial diagnostic hypothesis, because the previous lesion characteristics (both clinical and imaging) suggested it was an EC. After the proper histopathologic study, this hypothesis was refuted, and the lesion corresponded to a vascular malformation. Nevertheless, the treatment for this new diagnostic would be the same, as previously described by Matsuski T, et al. [8], where surgical treatment would be adequate when the lesion begins producing a malformation, in accordance with what the patient described: that within the last year the lesion had grown, enough to concomitantly increase the nuisances [8].

There is a wide variety of pathologies that affect the head and neck regions that may show similar characteristics, thus, to differentially discard diagnoses, clinical and radiological aspects must be taken into consideration, along with lesion localization. Such diagnostics are mainly EC, ranula, infection-related lesions, thyroglossal cyst, lipoma and saliva gland tumors [16]. Because of these distinct differential diagnoses, it is key to thoroughly analyze the clinical history to determine the possible etiology of the pathology and its evolution, as well as proceed with complete and thorough imaging studies, along with adjuvating exams, to accurately have a definitive diagnose and a treatment plan to follow.

Conclusion

Vascular malformations are a group of vascular anomalies thar generally require multidisciplinary treatment. Venous malformations may be misdiagnosed with other lesions such as EC because of common characteristics in various clinic and image modalities. Therefore, imaging studies are fundamental to proceed with an adequate diagnosis of these pathologies, followed by proper and specific treatments based on such diagnostic, and to discard different pathologies that show similar clinical and imaging characteristics, as with the clinical case described above.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Flors L, Park AW, Norton PT, Hagspiel KD, Leiva Salinas C (2019) Soft-tissue vascular malformations and tumors. Part 1: classification, role of imaging and high-flow lesions. Radiologia 61(1): 4-15.

- Guerra Cobián Orlando, Pupo Triguero Raúl Jorge, Sarracent Pérez Humberto (2012) Treatment of orofacial vascular malformations due to endoluminal sclerosis with laser diode. Rev haban medical science. 11( 4 ): 511-518.

- Janmohamed SR, Madern GC, de Laat PCJ (2015) Educational document: Pathogenesis of infantile hemangioma. Eur J Pediatr 174: 97-103.

- Jackson IT, Carreño R, Potparic Z, Hussain K (1993) Hemangiomas, vascular malformations, and lymphovenous malformations: classification and methods of treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg 91(7): 1216-1230.

- Gavín C Marina A, Mur T Andrea, Simón S Mª Victoria, Jariod F Úrsula Mª, Saura F Esther (2017) Arteriovenous malformation in the oral cavity: About a case and review of the literature. Rev Otorhinolaryngol Cir Head Neck 77(1): 69-72.

- Torres M Coral, Santana L Josefina, Bravo A Rodrigo, Mardones M Marcelo (2020) Vascular Anomalies of the Oral Cavity: Review of the Classification and Treatment Applied to Two Clinical Cases. Int J Odontostomat 14( 1 ): 48-54.

- Elias G, McMillan K, Monaghan A (2016) Vascular Lesions of the Head and Oral Cavity-Diagnosis and Management. Dent Update 43(9) :859-860, 862-4, 866.

- Takashi Matsuki, Kouki Miura, Yuichiro Tada, Tatsuo Masubuchi, Chihiro Fushimi, et al. (2019). Venous malformation of the parapharyngeal space: Two surgical case reports and a literature review. Otolaryngology Case Reports 13: 100130.

- Medeiros Jr R, Silva IH, Carvalho AT (2015) Nd:YAG laser photocoagulation of benign oral vascular lesions: a case series. Lasers Med Sci 30: 2215-2220.

- Jiménez Cesar E, Randial Leonardo, Silva Iván, Hossman Manuel, Rueda Juan David, et al. (2020) Treatment of vascular malformations and tumors, in a reference center in Bogotá. Rev Colomb Cir 35(4): 647-658.

- Arce V José D, García B Cristian, Otero 0 Johanna, Villanueva A Eduardo (2007) Vascular Anomalies of Soft Parts: Diagnostic Images. Rev Chil Radiol 13(3): 109-121.

- CM Tomblinson, GP Fletcher, TK Lidner, CP Wood, SM Weindling, et al. (2019) Oropharyngeal spatial venous malformation: a mimicking image of pleometic adenoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 40(1): 150-155.

- Wang D, Su L, Han Y, Wang Z, Zheng L et al. (2017) Direct intralesional ethanol sclerotherapy of extensive venous malformations with oropharyngeal involvement after a temporary tracheotomy in the head and neck: Initial results. Head Neck 39(2): 288-296.

- Sanz Lorena, Gamboa Francisco J, Rivera Teresa (2010) Epidermoid cysts of the floor of the mouth: presentation of two cases and review of the literature. Rev Esp Cirug Oral y Maxilofac 32(3): 115-118.

- Canto C Loreto, Pintor W Fernanda, Fernández T María de Los Ángeles, De La Fuente A Matteo, Bahamondes A Carlos (2016). Giant Hourglass Epidermoid Cyst of the Floor of the Oral Cavity. Int J Odontostomat 10(3): 507-512.

- Romero FJ, Pacheco RG (2016) Epidermoid cyst of the oral cavity. Case report and literature review. Rev Mex Cir Bucal Maxilofac 12(3): 80-85.

- Cruz V Marcia B, Cruz V Ludy, Castel B María I (2018) Unusual presentation of dermoid cyst in the floor of the mouth: case report and literature review. Square Hosp Clín 59(2): 50-54.

- Gómez Hernández KA, Morales Mercado R, Olmedo Campos BM, Tello Paniagua P (2021) Epidermoid cyst in parotid region. Case report and literature review. Odontol Sanmarquina 24(3): 277-284.

-

Edgardo Pineda Taladriz, Loreto Canto Contreras, Verónica Palacios, Diego Ramírez Villalobos and Sebastián Lazo Ruedlinger. Vascular Malformation Disguised as an Epidermoid Cyst in the Submental Area: Regarding A Clinical Case. On J Dent & Oral Health. 8(1): 2024. OJDOH.MS.ID.000678.

-

Oral cavity, Tongue, Mylohyoid muscle, Epidermoid cyst, Head and neck regions, Lymph vessels, Tissue tumor formation, Corticoids, Computerized tomography

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.