Research Article

Research Article

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors Association with Bruxism Among East Carolina Population

Amna Hasan*, Ashley Nethercutt, Julianne Yuziuk, Danish Hasan, Jamie Bloss, Iquebal Hasan, Gerard Camargo and Robert Keim

Department of Surgical Sciences, Division of Orofacial Pain, ECU School of Dental Medicine, USA

Amna Hasan, Department of Surgical Sciences, Division of Orofacial Pain, ECU School of Dental Medicine, USA.

Received Date: February 14, 2022; Published Date: March 14, 2022

Abstract

Bruxism affects roughly 5-20% of the adult population. It can be defined as a repetitive jaw-muscle activity characterized by clenching or grinding of the teeth and can occur during as a sleep-related disorder or during the daytime. Bruxism can irreversibly damage dentition and restorations and can also lead to temporomandibular joint disorders and headaches. The purpose of this study is to analyze the association of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) with bruxism among patients at East Carolina University School of Dental Medicine. This test population included 33,430 patients who were categorized by demographic and analyzed using IBM SPSS Version 27 to calculate distributions, frequencies, logistic regression, and Pearson’s Chi-Square analysis. SSRI and SNRI use were found to be a significant predictor of self-reported bruxism. Additionally, results indicated that male, Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Mixed, and other race were significantly less likely to report bruxism compared to reference categories of female and White. Female gender was found to be a significant predictor for self-reported bruxism. Limitations of this study included self-reporting bias from data recorded in the patient’s electronic health records, as well as the cross-sectional nature of the data collection preventing the monitoring of medication use and timing of symptoms. Future studies are needed to analyze the relationship between these medications and bruxism, especially regarding specific characteristics associated with each class of medications.

Introduction

Bruxism has been defined as a repetitive jaw-muscle activity characterized by clenching or grinding of the teeth and/or bracing or thrusting of the mandible during sleep or during wakefulness [1]. Sleep bruxism is recognized by the International Classification of Sleep Disorders as a sleep related movement disorder [1]. It may cause irreversible damage to dentition, damage to restorations, temporomandibular joint disorders, and headaches [2]. Approximately 5-20% of the adult population is affected by sleep bruxism and/or daytime bruxism [2-4]. While it’s exact physiology is currently unknown, there are several proposed mechanisms [2]. Studies have investigated a correlation between genetics and bruxism. However, most studies have not been able to prove causation due to bias, confounding variables, and inconsistent study methods [2]. Malocclusion has been another proposed cause of bruxism; however, many of these claims are expert opinions without evidence based backing [2]. Additionally, there is speculation that variations in neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, histamine, GABA, noradrenalin, acetylcholine are associated with the pathophysiology [2].

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) were created in the 1980s as a treatment for low serotonin levels, which was the proposed physiological cause of depression [5]. There are more than 14 varieties of serotonin receptors throughout the body [5]. The three main types of serotonin receptors are 5HT1A, 5HT2A/C, and 5HT3 [5]. The 5HT1A and 5HT2 receptors are thought to modulate mood, anxiety, and temperature [5]. In addition, the 5HT2 receptors are thought to modulate sexual function, sleep, compulsions, eating behaviors, panic attacks, hallucinations, and psychosis [5]. The 5HT3 receptors are believed to play a part in the regulation nausea, vomiting, appetite and gastrointestinal motility [5]. Presynaptic serotonin transporters have multiple binding sites for sodium, serotonin and SSRIs [5]. When the SSRI binds to the transporters, it creates negative allosteric modulation, decreasing the reuptake of serotonin from within the synapse back into the presynaptic neurons [5]. The increased levels of serotonin within the synapse increases binding to the serotonin receptors [5]. Over time, increased levels of serotonin due to SSRI function can lead to the desensitization of two of the three major serotonin receptor families, 5HT1A and 5HT2A [5].

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) are prescribed for many different conditions. While their primary use is to manage anxiety and depression, they can also be prescribed for various neurological, muscle, and skeletal pains as well as posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and dysmorphic disorders [6-8]. SNRIs block presynaptic serotonin and norepinephrine transporters from reuptake increasing the presence of the serotonin and norepinephrine between the synapses for stimulation of postsynaptic receptors [6]. SNRIs effect on serotonin receptors 5HT1A, 5HT2A/C, and 5HT3 is similar to SSRIs while the SNRI has the added effect on the norepinephrine alpha-2 adrenergic receptors [9].

SSRIs are the number one prescribed medication due to their ability to treat depression, obsessive compulsive disorders, eating disorders, anxiety disorders, and post traumatic stress disorder [5]. Systematic review of case reports supports an association between SSRI use and bruxism, although the current mechanism is unknown [3]. Bruxism, as a side effect of SSRI use, typically begins to appear three to four weeks after initiation of treatment, indicating adaptation of receptors as a possible cause [3]. One proposed mechanism of SSRI induced bruxism is that the increased levels of serotonin result in an increased level of dopamine release from the mesocortical tract [10-12]. This dopamine increase can increase the amount of disinhibition of movement in muscles throughout the body, including muscles of mastication [10-12]. Buspirone, a 5HT1A partial agonist, has been used successfully as a treatment for SSRI induced bruxism, further suggesting desensitization of the receptor as a cause [3]. Buspirone is known to increase dopaminergic neuron firing and the release of dopamine, which supports the idea that SSRIs cause bruxism by decreasing the effects of dopamine on the mesocortical tract [4].

SNRIs affect serotonin reuptake similar to SSRIs with the additional inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake. While the specific mechanism of action for SNRI induced bruxism is unknown, it is thought that, like SSRIs, increased levels of serotonin result in increased dopamine release from the mesocortical tract [12]. The effect of norepinephrine reuptake on bruxism is unknown [12]. While there are several different SNRIs, Venlafaxine shows the largest number of associated bruxism reports [12-14]. Venlafaxine is known to be thirty times more selective for serotonin reuptake inhibition than other SNRIs, supporting the proposed mechanism of action of increased serotonin levels leading to increased dopamine, thus resulting in increased muscle disinhibition [12, 15].

Since SSRIs and SNRIs are commonly prescribed medication for depression and the effects of bruxism are damaging, it is important to continue to search for an association between SSRI/SNRI use and bruxism. The aim of this study is to evaluate the correlation between SSRI/SNRI use and self-reported parafunctional habits to aid in clinical decision making.

Materials and Methods

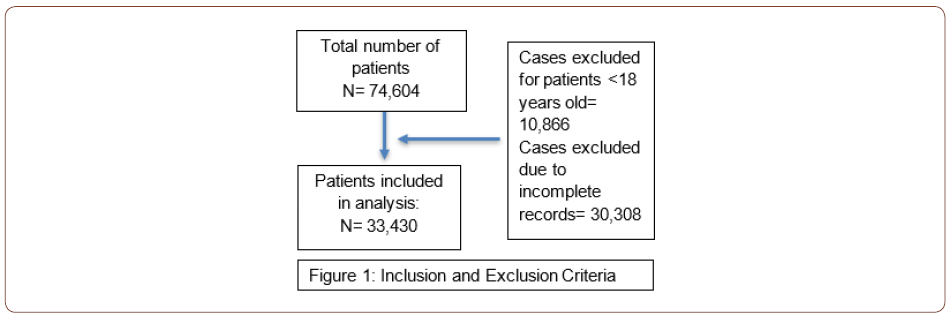

This study was certified exempt by the East Carolina University and Medical Center Institutional Review Board (20-001528). Participants include all East Carolina University School of Dental Medicine patients 18 years or older at the Ross Hall clinic and Community Service Learning Clinics. Inclusion criteria includes patients seen between April 12, 2013 and January 1, 2021, patients ≥18 years of age. Exclusion criteria include patients below the age of 18 and patients whose electronic health record did not have an answer for the questions on parafunctional habits (Figure 1). Data was retrieved de-identified from electronic health record (EHR) on the dental school’s software axiUm v7.04.08. Electronic health record data is added to a patient’s axiUm charts by dental students, assistants, residents, and faculty. A faculty dentist then approves and certifies the recorded data.

SSRI use was defined as a patient taking one or more of the following medications: Fluoxetine (Prozac, Selfemra, Rapiflux, Sarafem), Paroxetine (Brisdelle, Paxil, Paxil CR, Pexeva), Sertraline (Zoloft), Fluvoxamine (Luvox, Luvox CR), Citalopram (Celexa), Escitalopram (Lexapro), Vilazodone (Viibryd). SRNI use was defined as the patient taking one or more of the following medications: atomoxetine (Strattera), desvenlafaxine (Pristiq, Khedezla), duloxetine (Cymbalta, Irenka), levomilnacipran (Fetzima), milnacipran (Savella), venlafaxine (Effexor XR). Bruxism was defined as a self-reported yes answer to the question “habits: (tongue, finger, thumb, pacifier, bruxism, clenching)” in addition to a typed response including: bruxism, clenching, grinding, brux, clench, grind.

Results

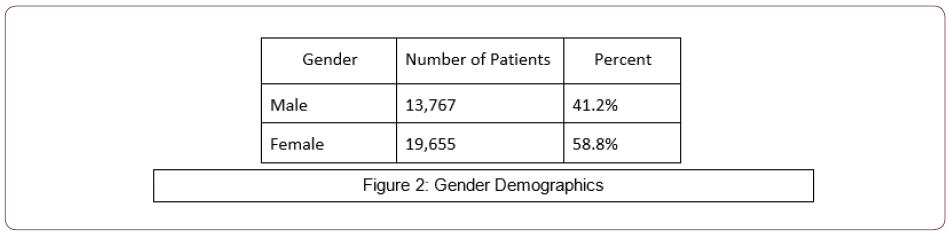

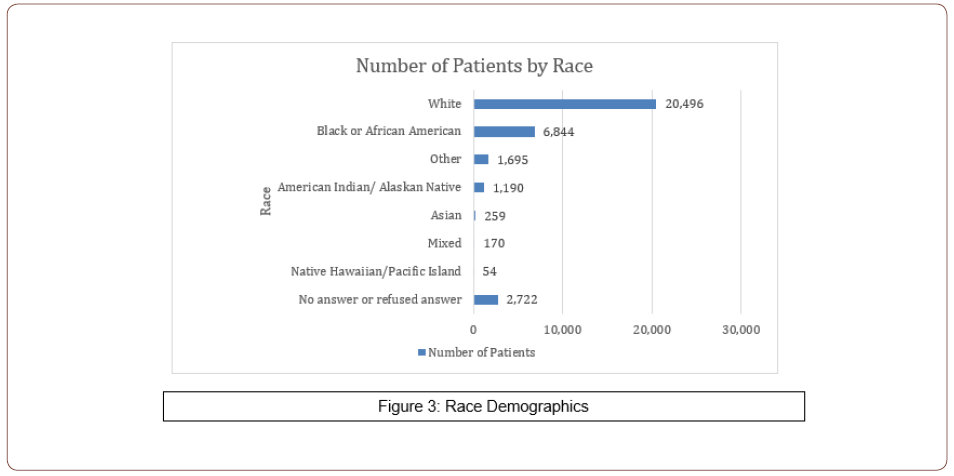

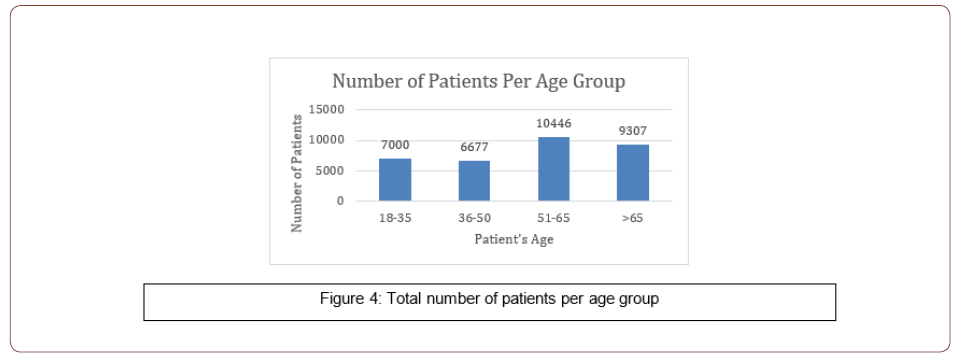

Demographics of the 33,430 test population included 41.2% male patients (13,767), 58.8% female patients (19,655), and 8 patients chose not to report (Figure 2). Self-reported demographics included 61.6% white (20,496), 20.5% black or African American (6,844), 5.1% other (1,695), 2.6% American Indian/Alaskan Native (1,190), 0.8% Asian (259), 0.5% Mixed (170), 0.2% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Island (54) and 8.1% not reported or refused reported (2,722) (Figure 3). Participants were categorized by age into the following groups: 18-35, 36-50, 51-65, and >65 years of age (Figure 4).

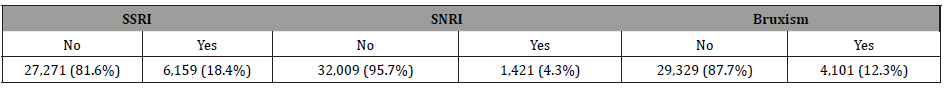

The data was analyzed using IBM SPSS Version 27 for calculating distributions, frequencies, logistic regression and Pearson’s Chi- Square analysis (Table 1).

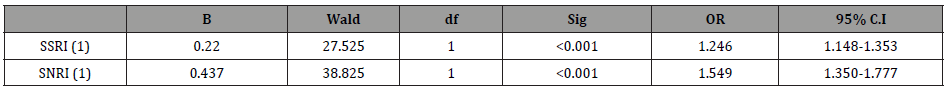

Potential associations between independent variables: SSRI, SNRI, sex, and race and the dependent variable: self-reported bruxism were explored using a logistic regression analysis. Results of the logistic regression analysis found SSRI use and SNRI use to be a significant predictor of self-reported bruxism (Table 2). Those taking SSRIs were 1.4x more likely to self-report bruxism than those who were not taking SSRIs (95% CI 1.33-1.563). Patients taking SNRIs were 1.7x more likely to self-report bruxism than those who were not taking SNRIs (95% CI 1.513-1.989). Results found male, Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Mixed, and other to be significantly less likely to report bruxism compared to the reference categories of female and white (Table 2).

Table 1: Frequencies of responses for SSRIs, SNRIs, and Bruxism.

Table 2: Logistic regression analysis results for SSRI and SNRI and self-reported bruxism among adult dental school patients. Reference categories were selected as the category with the majority of responses: SSRI-No, SNRI-No.

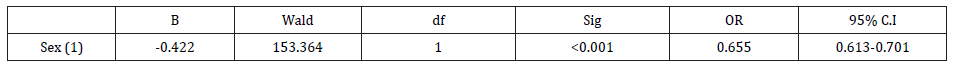

Results found female gender was a significant predictor for selfreported bruxism (Table 3). Female were 1.5x more likely to selfreport bruxism than males (95% CI 1.377-1.589) (Table 3).

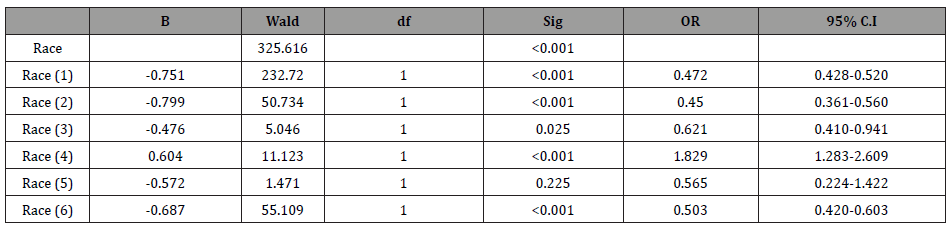

Results found Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, and other to be significantly less likely to report bruxism compared to the reference category White 9 (Table 4). Results found Mixed race as a significant predictor of bruxism compared to the reference category of White (Table 4). Results were not significant as protective or predictive for Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (Table 4). Black patients were 0.5x less likely to report bruxism than white patients (95% CI 0.428-0.520). American Indian and Alaskan Native patients were 0.5x less likely to report bruxism than white patients (95% CI 0.361-0.560). Asian patients were 0.6x as likely to report bruxism than white patients (95% CI 0.410-0.941). Mixed race patients were 1.8x more likely to report bruxism than white patients (1.283-2.609). Patient who selected other for their race were 0.5x less likely to report bruxism than white patients (95% CI 0.420-0.603) (Table 4).

Table 3: Logistic regression analysis results for sex and self-reported bruxism among adult dental school patients. Reference category was selected as: Sex-Female.

Table 4: Logistic regression analysis results for race and self-reported bruxism among adult dental school patients. Reference category was selected as the category with the majority of responses: Race-White. Race (1)-Black, Race (2)-American Indian/Alaskan Native, Race (3)-Asian, Race (4)-Mixed, Race (5)-Native Hawaiian/Pacific Island, Race (6)-Other.

Further post hoc bivariate testing was completed to search for associations between each variable. Chi-square analysis results found a significant association between self-reported bruxism and SSRI use (chi-square= 148.007, p< 0.001). Additionally, results found a significant association between self-reported bruxism and SNRI use (chi-square= 156.423, p< 0.001). There is a significant association between self-reported bruxism and sex (chi-square=179.572, p<0.001). There is a significant association between self-reported bruxism and race (chi-square=561.836, p<0.001).

Discussion and Conclusion

Results showed a significant association between SSRI use and self-reported bruxism as well as SNRI use and self-reported bruxism among dental school patients in North Carolina. These results should facilitate further discussion between dental clinical providers and primary care physicians to minimize the detrimental side effects of medications. While these results were significant, there were also significant associations found among sex and race data. These results show that the relationship between SSRI/SNRI and bruxism likely has many confounding variables which should be further evaluated to facilitate interdisciplinary discussions.

While these results found a significant association between SSRI/SNRI use and self-reported bruxism, there are limitations to this study. One limitation is results were based on self-reported symptoms of bruxism by patients allowing for reporting bias in patients reporting falsely one way or another. Results were recorded in the patient’s electronic health record by dental students, faculty, and staff. It was an attempt to limit reporting bias by excluding records where the question of parafunctional habits was not recorded. Another limitation of the study is that data was collected at a cross-sectional point in time. Results do not allow for monitoring when patients started these medications and when their bruxism began.

Further research is needed to explore relationships between specific medications within each class and bruxism. Additionally, longitudinal research could be conducted to analyze bruxism as it relates to when the medication was prescribed, the dosage of medication, and length of time the medication was being used. Further research could also be completed to explore potential relationships between these medications and clinical signs of bruxism. Until further research is completed, no changes should be made in the way these medications are being prescribed; however, these results should be a cause for further interdisciplinary conversation.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Lobbezoo F, Ahlberg J, Glaros AG, T Kato, K Koyano, et al. (2013) Bruxism defined and graded: an international consensus. J Oral Rehabil 40(1): 2‐4.

- Lavigne GJ, Khoury S, Abe S, Yamaguchi T, Raphael K (2008) Bruxism physiology and pathology: an overview for clinicians. J Oral Rehabil 35(7): 476‐494.

- Garrett AR, Hawley JS (2018) SSRI-associated bruxism: A systematic review of published case reports. Neurol Clin Pract 8(2): 135‐141.

- Uca AU, Uğuz F, Kozak HH, Haluk Gümüş, Fadime Aksoy et al. (2015) Antidepressant-Induced Sleep Bruxism: Prevalence, Incidence, and Related Factors. Clin Neuropharmacol 38(6): 227‐230.

- Stahl SM (1998) Mechanism of action of serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors. Serotonin receptors and pathways mediate therapeutic effects and side effects. J Affect Disord 51(3):215‐235.

- Nelson C, Roy-Byrne P, Solomon D (2020) Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): Pharmacology, administration, and side effects. UpToDate.

- Norris S, Blier P (2017) Duloxetine, milnacipran, and levomilnacipran. In: The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology, Fifth Edition, Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (Eds.), American Psychiatric Association Publishing, Arlington, VA, P: 529.

- Thase ME (2017) Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine. In: The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology, Fifth Edition, Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (Eds.), American Psychiatric Association Publishing, Arlington, VA P: 515.

- Yuen EY, Qin L, Wei J, Liu W, Liu A, et al. (2014) Synergistic regulation of glutamatergic transmission by serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors in prefrontal cortical neurons. J Biol Chem 289(36): 25177-25185.

- Falisi G, Rastelli C, Panti F (2014) Psychotropic drugs and bruxism. Expert Opin Drug Saf 13: 1319-1326.

- Chen WH, Lu YC, Lui CC (2005) A proposed mechanism for diurnal/nocturnal bruxism: hypersensitivity of presynaptic dopamine receptors in the frontal lobe. J Clin Neurosci 12: 161-163.

- Rajan R, Sun YM (2017) Reevaluating Antidepressant Selection in Patients with Bruxism and Temporomandibular Joint Disorder. J Psychiatr Pract 23(3): 173-179.

- Kuloglu M, Ekinci O, Caykoylu A (2010) Venlafaxine-associated nocturnal bruxism in a depressive patient successfully treated with buspirone. J Psychopharmacol 24: 627-628.

- Chang JP, Wu CC, Su KP (2011) A case of venlafaxine-induced bruxism alleviated by duloxetine substitution. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 35: 307.

- Montgomery SA (2008) Tolerability of serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressants. CNS Spectr 13: 27-33.

-

Amna Hasan, Ashley Nethercutt, Julianne Yuziuk, Danish Hasan, Jamie Bloss. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors Association with Bruxism Among East Carolina Population. On J Dent & Oral Health.5(4): 2022. OJDOH.MS.ID.000616. DOI: 10.33552/OJDOH.2022.05.000616.

-

Teeth, Sleep bruxism, Eating disorders, Mesocortical tract, Anxiety disorders, Vomiting, Pathophysiology, Sleep-related disorder, Bruxism.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.