Short Communication

Short Communication

Oral Cavity and HIV Infection

Marcelo Corti1,2*

1Chief of HIV/AIDS Department, Infectious Diseases F. J. Muñiz Hospital, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2Head of Medicine Department, Infectious Diseases Orientation, University of Buenos Aires, School of Medicine, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Marcelo Corti, Department of HIV/AIDS, Infectious Diseases F. J. Muñiz Hospital, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Received Date: June 17, 2020; Published Date: July 06, 2020

Introduction

The immunosuppression associated with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and its consequence the Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), predisposes to a large series of opportunistic infections (OI) and neoplasms, such as Kaposi´s sarcoma (KS) and non-Hodgkin lymphomas [1,2]. These clinical complications are named as AIDS-defining diseases. AIDS defining illnesses include a group of pathologies whose incidence in the HIV individuals is much bigger compared with the general population. Oral cavity is a frequent engagement site in all stages of the natural history of HIV infection. The knowledge of these oral cavity clinical manifestations should suggest to the dentist the possibility of HIV infection and to investigate the serological status of the patient. For this reason, oral cavity should be carefully examined in all patients. Oral cavity manifestations of HIV infection should be classified in two groups; nonspecific clinical lesions and those directly related with the progressive immunosuppression.

Unspecific Lesions

Unspecific clinical lesions include the periodontal disease affecting the gums and dental support structures. These diseases have been classified as gingivitis, when limited to the gums, and periodontitis, when they spread to deep tissues. The linear gingival erythema (Figure 1), frequently observed in HIV/AIDS patients, is characterized by a red linear in the gingiva, near the dental arch. In patients with advanced stages of the retroviral disease ulcerative and necrotizing gingivitis can be observed. Clinical manifestations include fetid breath, gingival erosions, enamel alterations and tooth loosening [3]. HIV-infected patients can present different ulcerative lesions in the oral cavity. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis is characterized by single or multiple painful ulcerative lesions on the lateral edge of the tongue, oral mucosa and lips. These lesions can be treated with corticosteroids or thalidomide [4].

Sexually Transmitted Diseases with Oral Involvement

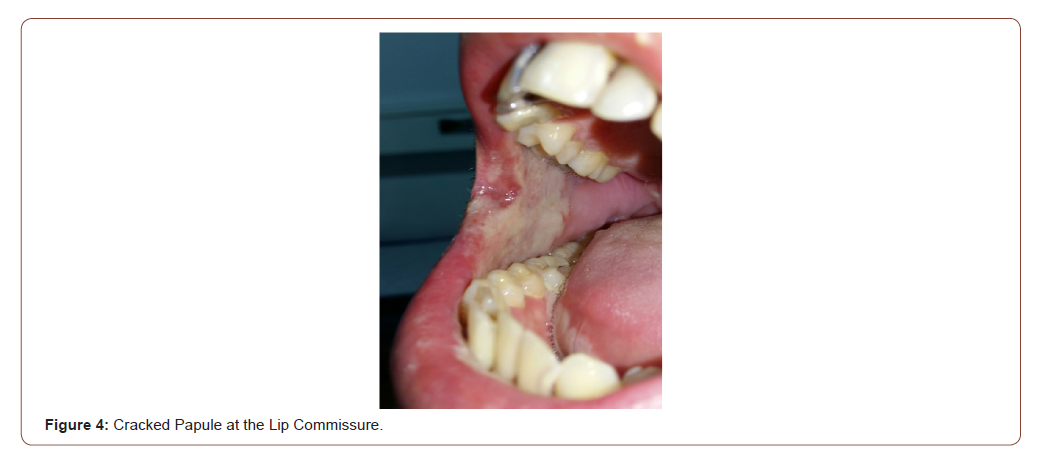

All the sexually transmitted diseases (STD) may have expression in the mouth; the mouth may be the site of frequent location of the syphilitic chancre (extragenital chancre) and the oral cavity can be the site of the secondary syphilis lesions. Mouth syphilitic chancre can be located anywhere into the mouth, including the tongue (Figure 2), the lips, the gums, the pharynx and the tonsils. Generally, syphilitic chancre is a single and painless lesion, but in conditions of immunodeficiency, as the HIV infection, the chancre lesions can be multiple. Symptoms of secondary syphilis include skin rash, swollen lymph nodes, fever and systemic symptoms. Secondary syphilis has multiple manifestations in the oral cavity, as the tongue papular lesions, the lichenoid lesions (opaline syphilis) (Figure 3), lingual depapilation, cracked papule at the lip commissure (Figure 4) and erosions in the oral mucosa [5].

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is the etiologic agent of the most common sexually transmitted infection, named as genital warts or condylomata. Infection by the human papillomavirus (HPV) can also present intraoral warts (Figure 5) generally located in the oral mucosa [6]. Additionally, HPV is related with the pathogenic of 45% to 90% of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma [7,8]. Generally, these malignancies appear after a long period of HIV infection; previous studies showed that HAART has not reduced the prevalence of HPV infection and has not declined the incidence of high grade anal, cervical or oral squamous epithelial lesions [9]. Gonococcal pharyngitis should be recognized and treated to avoid a reservoir of the Neisseria gonorrhoae.

Acute Primary HIV Infection

Acute primary HIV infection or acute HIV retroviral syndrome is symptomatic in more than 60% of patients. The most common clinical manifestation is a mononucleosis- like-syndrome with fever, headache, malaise, myalgia, arthralgia, a diffuse erythematous rash and a pseudomembranous or erithematous pharyngitis. Cervical symmetrical lymphadenopathy is also frequent. Mucocutaneous oral ulcerations and oral candidiasis have been reported in rare cases [10,11].

Opportunistic Infections of Oral Cavity

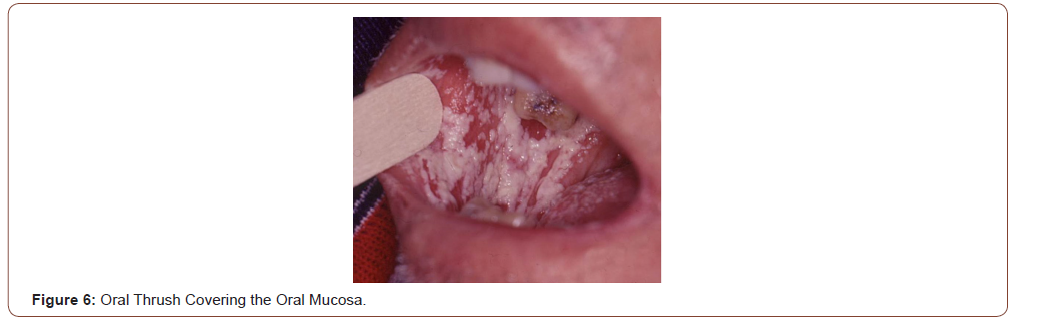

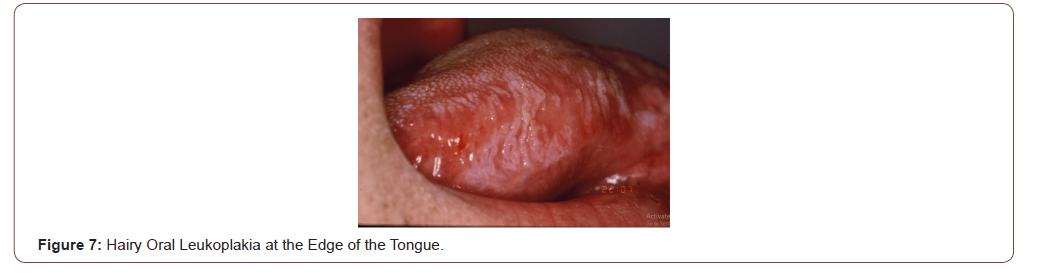

OI that can be seen in the oral cavity include bacterial, fungal, viral and parasitic diseases. The most frequent OI related with HIV is the oral thrush. Oral thrush is caused by an overgrowth of the fungus Candida albicans. Candidiasis is a prominent manifestation of HIV disease. This OI can be asymptomatic or produce dysphagia; is characterized by white or yellow patches of bumps on the inner cheeks, tongue, tonsils, gums, or lips (Figure 6); in some cases, oral thrush can affect the esophagus. Oral thrush is a manifestation of immunodeficiency in HIV individuals and should always make the suspicious of HIV status [12]. Same as the oral thrush, the hairy oral leukoplakia is other non-AIDS-defining disease with oral manifestation as a white lesion typically located at the edges and the tip of the tongue (Figure 7). Hairy oral leukoplakia is strongly related with the immunodeficiency of HIV infection and it can be seen in patients with less than 400 CD4 T-cell counts. Oral hairy leukoplakia is a condition related with the Epstein-Barr virus in his pathogenesis [13].

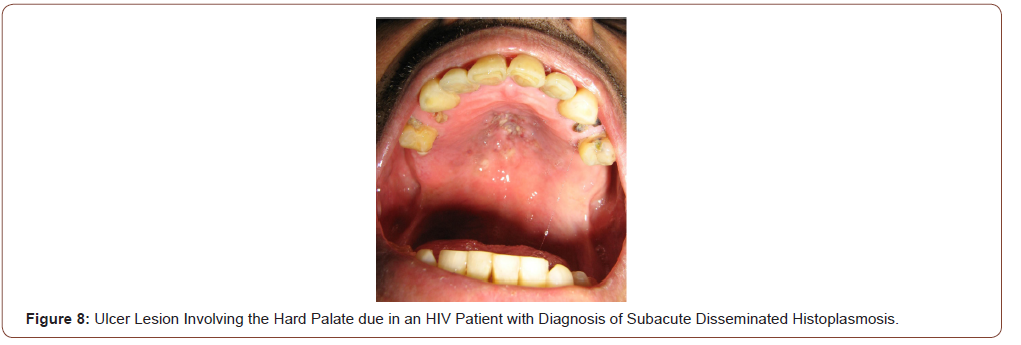

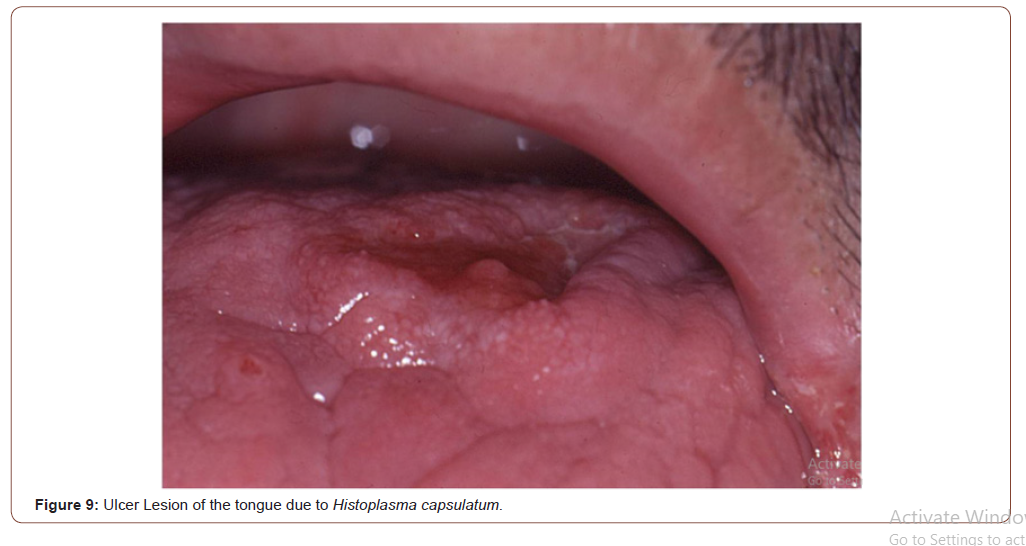

Histoplasmosis is an endemic mycosis caused by a dimorphic fungus, Histoplasma capsulatum. Histoplasmosis is a fungal disease most prevalent in patients with advance HIV/AIDS disease and CD4 +T cell counts less than 100 cells/μL. Acute and subacute disseminated forms of the disease result from reactivation of latent infection and are much more severe in patients with AIDS compared with other immunodeficiencies. The disseminated forms of the disease, affects the immunocompromised patients, especially HIV subjects with a CD4 T-cell count below 200 cell/μL, and may affect multiple organs: lungs, bone marrow, spleen, adrenal glands, liver, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, skin and oral mucosa. In some cases, oral lesions appear to be the only primary manifestation of the disease and may compromise the tongue, palate or the oral mucosa (Figure 8, 9).

Prolonged fever, bilateral lung involvement, papules and ulcerative cutaneous lesions and frequent oral mucosal lesions are generally observed. Oral cavity lesions can involve hard palate, uvula, tongue, gingival, tonsils and pillars with painful ulcers for several weeks. Diagnosis can be rapidly confirmed by the scarification or the biopsy of these lesions. Histologic findings of histoplasmosis with hematoxylin and eosin stain typically show diffuse lymphohistiocytic infiltrates with fungal elements about 2-4 μm in size detected within the cytoplasm of histiocytes and macrophages compatible with yeats of H. capsulatum. Well-formed granulomas are generally rare in HIV patients. Special stains, such as Grocott methenamine silver and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) methods are also useful in visualizing the fungal elements and highlight the fungal organism cell wall. The clinical differential diagnosis of oral histoplasmosis is broad and ranging from non-specific ulcers to malignancy [14].

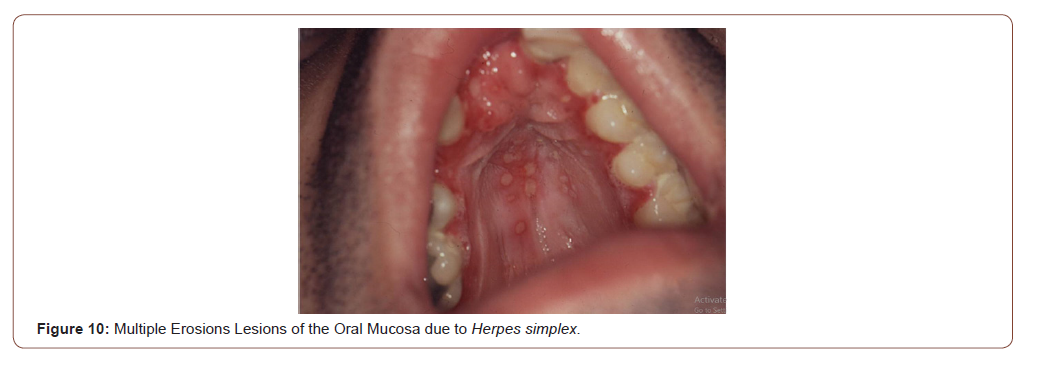

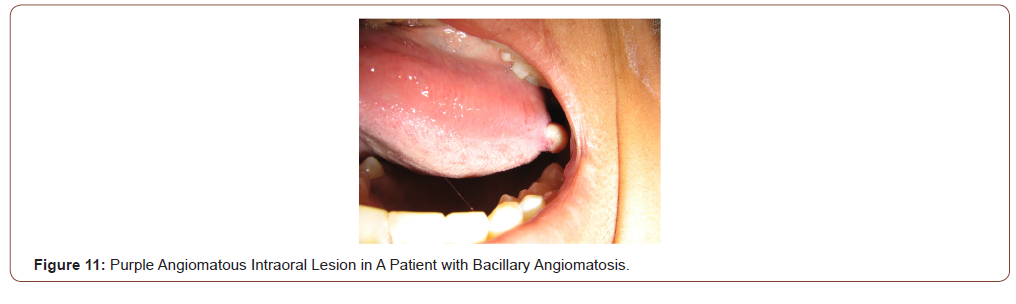

Viral infections such as Herpes simplex type I or II are to be considered in the differential diagnosis of erosive or ulcerative lesions that compromise the oral mucosa (Figure 10). Generally, the Tzanck cytodiagnosis demonstrate classic viral cytopathic effect, known as ballooning degeneration (viral syncics). Tzanck test is a quick and useful method in the diagnosis of different mucocutaneous conditions [15,16]. Bacillary angiomatosis is an unusual infectious disease, with angioproliferative lesions, typical of immunocompromised patients especially advanced HIV/AIDS disease. It is caused by Bartonella quintana and Bartonella henselae, two infectious agents of the genus Bartonella, which a variable clinical manifestations, including cutaneous vascular and nodular or tumor cutaneous violaceous lesions, regional lymphadenopathy, and even a systemic disease with visceral involvement. Purple angiomatous lesions can also locate in the oral cavity and the rhinopharynx (Figure 11). These lesions must be differentiated of the oral KS [17].

Parasitic infections, such as mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, may be rare in HIV patients, but should be investigated to exclude this unusual infection. The Tzanck cytodiagnosis can bring out amastigotes of Leishmania spp within the macrophages [14,16].

Neoplastic Diseases with Oral Involvement

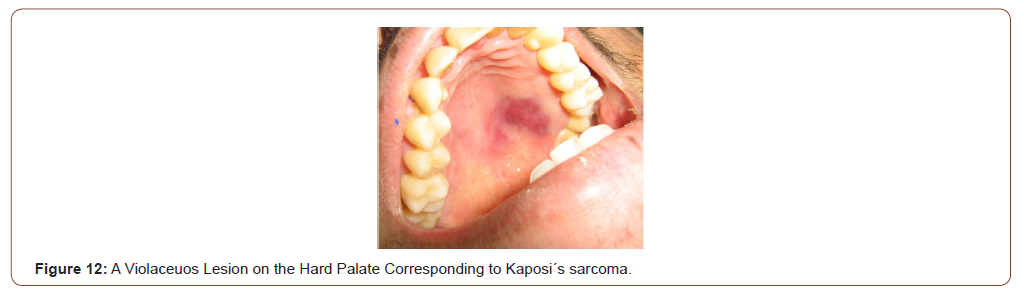

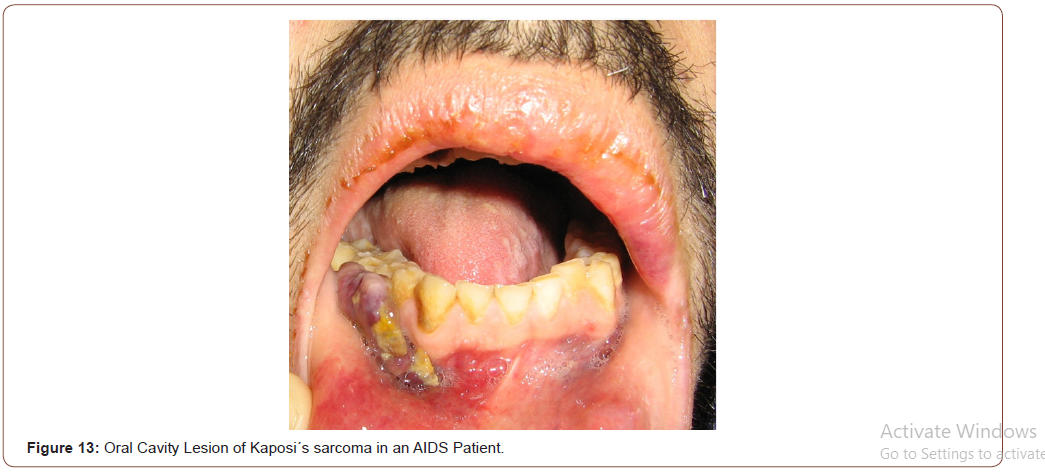

KS is a malignant neoplasm, strongly associated with Human Herpes Virus 8 (HHV-8) in its pathogenesis. Lesions of KS can disseminate rapidly in severely immunocompromised HIV patients, with cutaneous, mucosal and visceral involvement. In advanced HIV/ AIDS disease, KS has a very aggressive clinical course with frequent involvement of lymph nodes, the lungs and the gastrointestinal tract in 50% of the cases. Lungs involvement occurs in 20% of the patients and is the most frequent cause of mortality. In the oral cavity, the most common sites involved by KS are the hard palate and the gums (Figure 12, 13). An intraoral examination generally revealed non-ulcerated, purple nodular lesions [18,19].

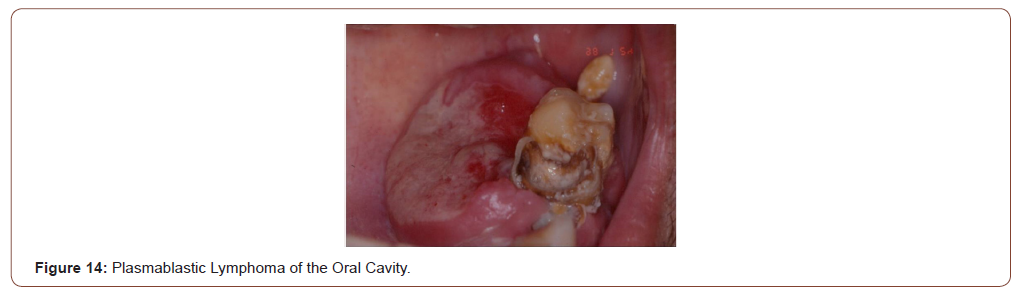

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a common complication of the disease caused by the HIV. The involvement of the digestive tract, from the oral cavity to the anus region, is very frequent [2]. Gastrointestinal tract involvement is also frequent in HIV-infected patients account 15% to 75% of all cases [1,2,20]. More than 40% of extranodal NHL involve the digestive tract. Oral cavity is a frequent site with a highest commitment [21]. NHL of the oral cavity can involve the tongue, gingiva, hard palate, Waldeyer’s ring, palatine and lingual tonsils, and can present clinically as mass lesions covered by an intact or ulcerated mucosa [22-24]. In HIV-infected patients, the most frequent subtypes include diffuse large B-cell lymphoma DLBCL), Burkitt lymphoma (BL) and plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL).

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a rare entity typically described in the oral cavity of HIV-infected patients [25,26] (Figure 14). The World Health Organization (WHO) classified the PBL as a diffuse proliferation of large neoplastic cells in which the majority of the tumour cells show the immunophenotype of plasma cells (CD138 and VS38c positive) [27]. PBL seems closer to DLBCL; the differential diagnosis between DLBCL and PBL is performed on a clinical, morphological and phenotyphical findings. PBL accounts for approximately 3% of all HIV-related non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL) and is strongly associated with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in its pathogenesis [27-29].

Conclusion

Oral lesions are common findings in HIV-infected patients especially in those with CD4+ cell counts <200 cells/μL. In a recent study, 60.0% of the oral lesions were diagnosis in patients with CD4+ T-cell counts <200 cells/μL [30]. The most common oral lesion identified in this kind of patients is the oral candidiasis as OI and the KS of the oral cavity as tumor lesion. The main factor associated with the development of oral lesions is the CD4+ T-cell count less than 400 cell/μL. A diagnosis of certain oral lesions should make the condition suspect of HIV positive serological status. Progression of infection is associated with a high prevalence of certain oral lesions, including oral thrush, hairy leukoplakia, and neoplasms.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Danzig JB, Brandt LJ, Reinus JF, Klein RS (1991) Gastrointestinal malignancy in patients with AIDS. Am J Gastroenterol 86: 715-718.

- Heise W, Arastéh K, Mostertz P, J Skörde, W Schmidt et al. (1997) Malignant gastrointestinal Lymphomas in patients with AIDS. Digestion 58: 218-224.

- Rowland RW, Escobar MR, Friedman RB (1993) Painful gingivitis may be an early sign of infection with the human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 16: 233-236.

- Mac Phail LA, Greenspan D, Greenspan JS (1992) Recurrent aphthous ulcers in association with HIV infection: Diagnosis and treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 73: 283-288.

- Baughn RE, Musher DM (2005) Secondary syphilitic lesions. Clin Microbiol Rev 18: 205-216.

- Corti M (2017) Relation between HPV Infection and the Pathogenesis of the Extra Anogenital Squamous Cell Carcinomas in HIV Positive and Negative Patients. Austin J HIV/AIDS Res 4: 1035-1037.

- De Vuyst H, Clifford GM, Nascimento MC, Madeleine MM, Franceschi S (2009) Prevalenceand type distribution of human papillomavirus in carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva, vagina and anus: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 124: 1626-36.

- Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S (2005) Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14: 467-475.

- Severini A (2011) Anal intraepithelial neoplasia in men living with HIV in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 52: 1182-1183.

- Cooper DA, Gold J, Maclean P (1985) Acute AIDS retrovirus infection. Definition of a Clinical illness associated with seroconversió Lancet 1: 537-540.

- Fox R, Eldred LJ, Fuchs EJ, R A Kaslow, B R Visscher, et al. (1987) Clinical manifestations of acute infection with human immunodeficiency virus in a cohort of gay men. AIDS: 35-38.

- Greenspan D, Greenspan JS (1987) Oral mucosal manifestations of AIDS. Dermatol Clin 5: 733-737.

- Feigal DW, Katz MH, Greespan D, J Westenhouse, W Winkelstein, et al. (1991) The prevalence of oral lesions in HIV-infected homosexual and bisexual men: three San Francisco epidemiological cohorts. AIDS 5: 519-525.

- Folk G, Nelson BL (2017) Oral histoplasmosis. Head and Neck Pathol 11: 513-516.

- Tzanck A (1947) Le cytodiagnostic immediate en dermatologie. Bull Soc Fr Dermat Syph 7: 68.

- Bianchi M, Santiso G, Lehmann E, Walker L, Arechavala A (2012) Usefulness of Tzanck cytodiagnosis test in an infectious diseases hospital, in Buenos Aires city, Argentina. Dermatol Argent 18: 42-46.

- Uribe P, Balcells E, Giesen L, Cárdenas C, García P, et al. (2012) Angiomatosis bacilar por Bartonella quintana como primera manifestación de infección por VIH. Rev Med Chile 140: 910-914.

- Corti M, Correa J, Nano M, Saccheri C, Lewi D, Campitelli AL (2018) Disseminated Kaposi’s sarcoma as primary manifestation of AIDS. Clin Oncol 3: 1532-1533.

- Corti M, Villafañe MF, Metta H, Trione N, Baré P, Gilardi L (2016) Detection of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated human herpes virus type 8 DNA in biopsy smears of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Glob Dermatol 3: 238-240.

- Mitrou PS, Serke M, Pohl C (1991) Malignant lymphomas associated with HIV infection. Dtsch med weekly 116: 1217-1223.

- Boddie AW, Mullins JD, West G, Bouda D (1982) Extranodal lymphoma: surgical and other therapeutic alternatives. Curr Probl cancer 6: 1-63.

- Corti M, Villafañe MF, Valerga M, Sforza R, Bistman A (2015) Burkitt’s lymphoma of the oral cavity in a female with AIDS. Case report and literature review. Rev Esp Cir Oral Maxilo Fac 37: 44-47.

- Pérez G, Maquera-Afaray J, Linares S, Castillo R (2017) Burkitt’s lymphoma of the tonsil in HIV patient, associated to occipital tumor and osteolytic lesions in the cranial vault. Acta Med Peru 34: 52-56.

- Corti m, Villafañe MF, Cermelj M, Candela M, pérez Bianco R, et al. (2000) Cavum lymphoma in a hemophilic patient with AIDS. Medicina (Buenos Aires) 60: 351-353.

- Delecleuse HJ, Anagnostopopous I, Dallencbach F, M Hummel, T Marafioti, et al. (1987) Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood 89: 1413-1420.

- Cioc AM, Allen C, Kalmar JR, Saul Suster, Robert Baiocchi, et al. (2004) Oral plasmablastic lymphomas in AIDS patients are associated with human herpesvirus 8. Am J Surg Pathol 28: 41-46.Kane S, Khurana A, Parulkar G, Tanuja Shet, Kumar Prabhash, et al. (2009) Minimum diagnostic criteria for plasmablastic lymphoma of oral/sinoseal region encountered in a tertiary cancer hospital of a developing country. J Oral Pathol Med 38: 138-44.

- Guan B, Zhang X, Ma H (2010) A meta-analysis of highly active anti-retroviral therapy for treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma. Ann Saudi Med 30: 123-128.

- Corti M, Villafañe MF, Bistman A, Campitelli A, Narbaitz M, et al. (2011) Oral cavity and extra-oral plasmablastic lymphomas in AIDS patients: report of five cases and review of the literature. Int J STD & AIDS 22: 759-763.

- Berberi A, Aoun G (2017) Oral lesions associated with human immunodeficiency virus in 75 adult patients: a clinical study. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 43: 388-394.

-

Marcelo Corti. Oral Cavity and HIV Infection. On J Dent & Oral Health. 3(2): 2020. OJDOH.MS.ID.000556.

-

Neoplasms, Oral cavity, Gingivitis, Tongue, Oral mucosa, Thalidomide, Oral squamous, Neisseria gonorrhoae, Parasitic diseases, Oral leukoplakia.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.