Research Article

Research Article

Evaluation of a Topical Phenytoin on Gingival Wound Healing

Dr. Mehdi Honarparvar, Centro Escolar University Graduate School Manila, Philippine, USA, Email: mehdi.honarparvar@yahoo.com.

Received Date: December 20, 2019; Published Date: January 21, 2020

Abstract

The study aimed to evaluate the wound healing activity of topical phenytoin on gingival wound healing. In particular, 24 rabbits with the same gender, race and diet were kept in the same environment and were divided into two groups: Twelve (12) for the experimental group and another (12) for the control group. Each rabbit was prepared for surgery. The study focused on the clinical analysis in terms of color, size and gross appearance of the sound. Likewise, it also focused on the histopathological appearance of the wound for 1, 2 and 4 weeks with regard to polymorphonuclear cells, fibroblast and epithelialization.

Findings related that in terms of color, no significant differences were observed during the 1st, 2nd, and 4th week on both control and experimental group A because the pink color was consistently present. Significant improvement in size from the 1st to 4th week of the control and experimental group occurred because significant decrease in size from the 2nd to the 4th week. Meanwhile there was a significant difference in the gross appearance from the 2st to 4th week of the control group because the edema became normal on the 2ndand 4th weeks. It was therefore concluded that the experimental group is effective in 1st week decreasing the size, normalizing the gross appearance, decreasing of polyphon clear cells and increasing epithelialization. On the other hand, it cannot lessen the fibroblast. Finally effect of experimental is almost similar with control after 4th week.

Introduction

Proper wound healing processes are important in the prevention of complications (i.e. post-operative infection) which may lead to the formation of scar tissue that compromises esthetics. This would indicate that the acceleration of wound healing might be an important target in medicine. In dentistry, gingival wound healing comprises a series of sequential responses that allow the closure of breaches in the masticatory mucosa. This process is of critical importance to prevent the invasion of microbes or other agents into tissues, avoiding the establishment of a chronic infection. Wound healing may also play an important role during cell and tissue reaction to long-term injury [1]. Wound healing is very important and should always address the needs of the patient, promote normal healing and prevent complications. Dressings applied to acute wounds may require review by the patient themselves so clear instructions are necessary on what to do, when to do it and what should be raised as a concern. Surgical wounds are usually left covered for up to a week after surgery. In the case of graft donor sites, the dressing is left for up to 2 weeks [2].

Phenytoin is an example of agent that has been widely studied for its supposed benefits albeit controversial effects in wound healing. Oral phenytoin is used widely for the treatment of convulsive disorders, particularly as an effective anticonvulsant against tonic-clinic and partial seizures. A common side effect with phenytoin treatment of is the development of fibrous overgrowth of gingival tissues. This apparent stimulatory effect of phenytoin on connective tissue suggests the possibility for its use in wound healing, promoting numerous investigations on its contribution to wound healing processes [3].

Method of Research

This study utilized the experimental method of research. This methodology relied on random assignment and laboratory controls to ensure the most valid, reliable results. Although the researcher recognized that correlation does not mean causation, experimental designs produce the strongest, most valid results.

Procedures of data gathering

The test animals in the study were composed of 24 rabbits divided equally into two groups (experimental and control). For the experimental group, 6 rabbits underwent horizontal incision on the upper maxillary anterior labial part while 6 rabbits underwent horizontal incision on the lower mandibular anterior labial part. General anesthesia was then administered in 10 to 15 minutes to the rabbits. After this, sterile water was utilized in cleaning the affected area and then 1% phenytoin was applied. The same protocol was applied for the control group except for the topical PHT application. For the first, second and fourth weeks, 24 test animals respectively were sent to the laboratory. Likewise, per any week 4 rabbits from the experimental as well as 4 other rabbits from the control group were introduced. They were all observed from first to four weeks in the laboratory for histological and clinical analysis.

Phenytoin preparation

Preparation of phenytoin mucoadhesive paste 1% Phenytoin mucoadhesive paste 1% was prepared. As part of the preparation of this, 1 mg of phenytoin capsule was mixed with 100 mg of mucoadhesive paste compositions (including polyethylene LD, liquid paraffin, gelatin powder, lemon pectin powder, sodium carboxy methylcellulose powder, equal from each one). The resulting paste was deposited into 100mg tubes [4].

Results

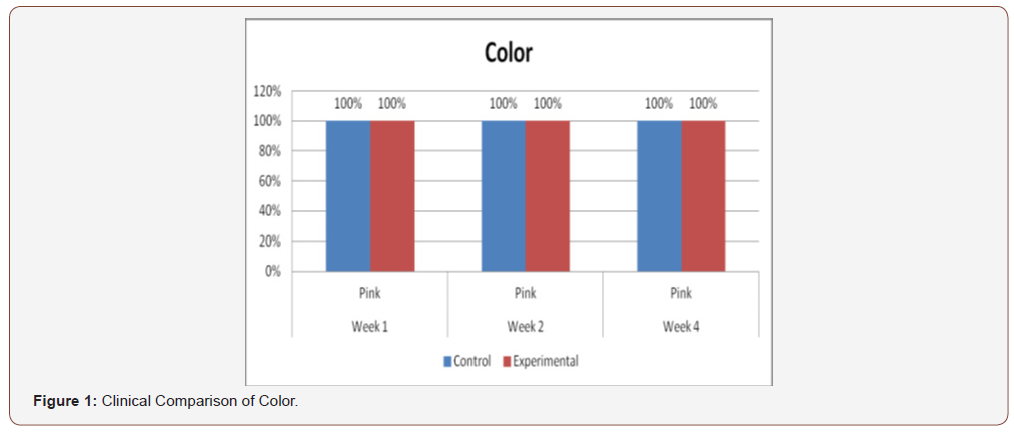

(Figure 1) demonstrates the comparison of clinical analysis of color between control and experimental groups on the 1st, 2nd, and 4th weeks’ observation. No significant differences were observed with p-value above 0.05 (p=1.00) at all observations.

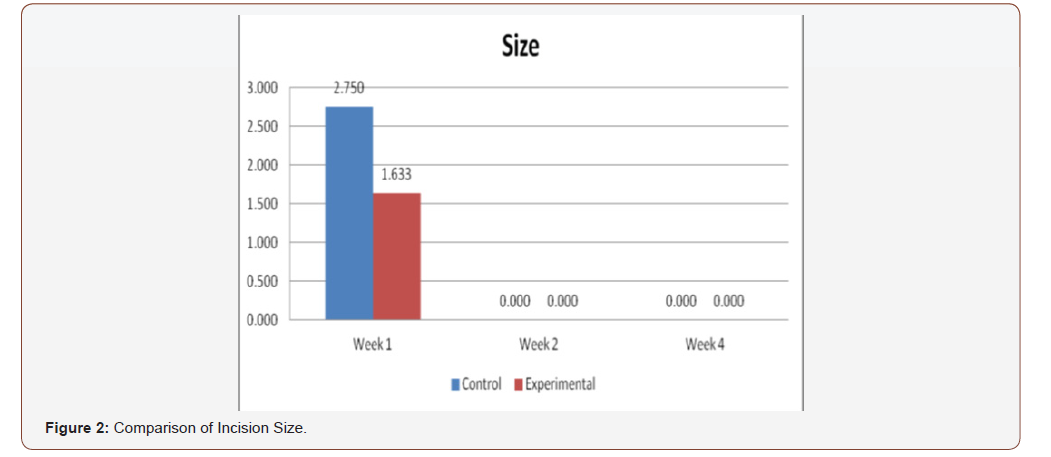

(Figure 2) displays the comparison of clinical analysis of size between control and experimental groups on the 1st, 2nd, and 4th week’s observation. No significant differences were observed on 2nd and 4th week with p-value above 0.05 (p=1.00). However, significant differences were observed on week 1 (p=0.017).

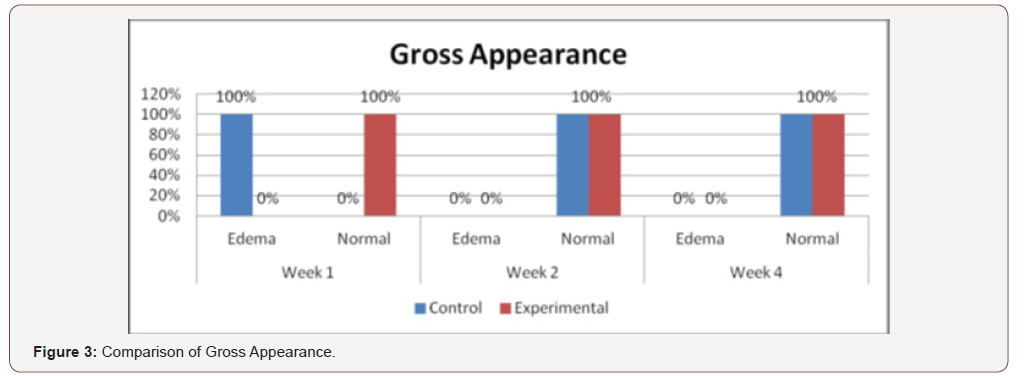

(Figure 3) shows the comparison of clinical analysis of gross appearance between the control and experimental groups on the 1st, 2nd and 4th week’s observation. No significant differences were observed on 2nd and 4th week with p-value above 0.05 (p=1.00). Statistically significant differences were observed on week 1 (p=0.005) only.

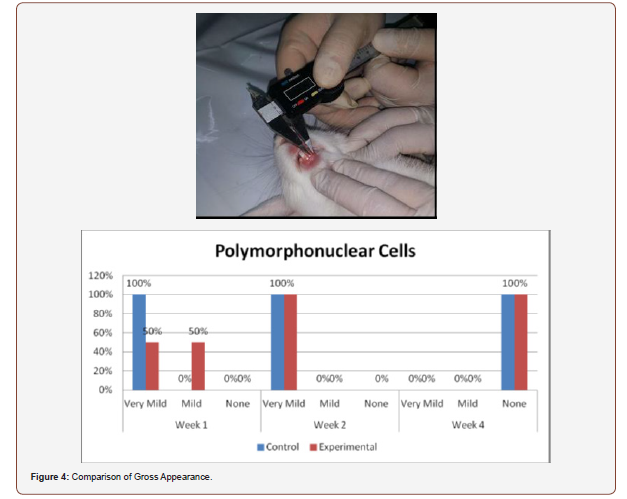

Figure 4) shows the comparison of histologic counts of polymorphonuclear cells between the control and experimental groups on the 1st, 2nd and 4th weeks’ observation. No significant differences were observed within all the observation periods (p =0.102, 1.000, 1.000).

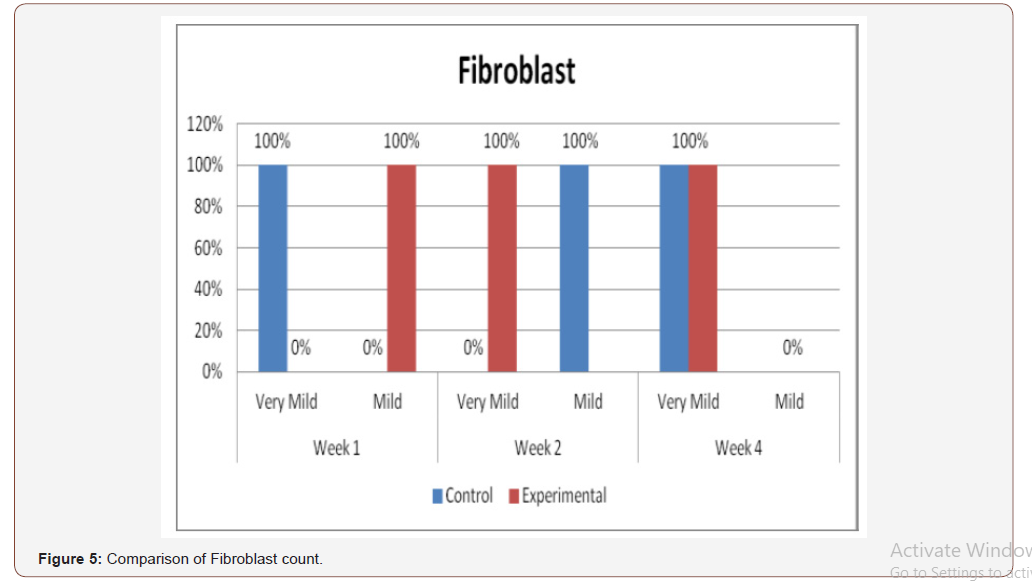

(Figure 5) presents the comparison of histologic analysis of fibroblast count between the control and experimental groups on 1st, 2nd and 4th weeks observation. Significant differences on fibroblast numbers were seen between the 2 groups on the 1st and 2nd weeks of observation (p=0.005).

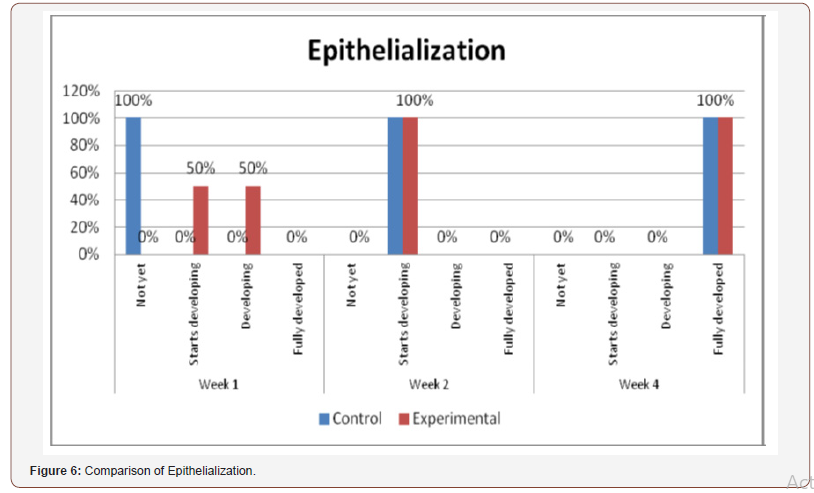

(Figure 6) shows the comparison of histopathological analysis of epithelialization between control and experimental groups on 1st, 2nd and 4th weeks observation. No significant differences were observed on 2nd and 4th weeks (p=1.00). Significant differences were only observed on week 1 (p=0.018) (Figures 7-12).

Histological Analysis

Inconsistent results were seen in the analysis of the fibroblast presence. For the control group, an expected increase in fibroblast count was noted from the 1st to the 2nd week, in accordance with physiologic remodeling of the epithelium following injury. But on the 3rd week, very minimal fibroblasts were seen compared to the previous (2nd) week. A comparison of the fibroblast count of the 1st week shows a significant difference (p = 0.005) in favor of the PHT-treated group. This phenomenon can be attributed to PHT’s well-documented induction of hyperproliferation of fibroblast cells, with concomitant increase in collagen production (Ghanpachi 2013) [5-13]. However, more fibroblasts were seen on the control group on the 2nd week. The inability of the test group to maintain the increased fibroblast production might be due to the localized (i.e. non-systemic) and single-dose application of PHT, leading to minimal concentrations of the drug, with an accompanying short duration of activity [14-21]. Analysis of the samples showed an expected decrease (albeit minimal) in the numbers of polymorphonuclear cells (PMN) for both control & test groups following incision (from the 1st to the 2nd week), followed by a sharp reduction, with no histologically visible cells in the 4th week. However, no differences in the amount of the said decrease in PMN cells were found between the 2 groups, despite the findings of some studies that document phenytoin’s immunosuppressive activity (Przegl Lek 2008) [21-30]. PHT’s reported acceleration of healing of epidermal wounds has been associated with its interaction with glucose transporter protein-1 (GLUT-1) presence in the epidermal basal layer. Oral epithelium lacks this said protein, which might in turn affect the longevity and/or effect of PHT on wound healing of this particular epithelium [3].

Clinical Analysis

Clinical analysis of the color of the tissues surrounding the incisions show no differences between the 2 groups at all weekly intervals (p = 1.00). Several studies on PHT’s acceleration of wound healing on the epidermis characterize the said wounds as either being the result of traumatic injuries (i.e. accidents) or pathologies (i.e. leprosy). The experimental wounds in this study were single linear incisions made by a scalpel blade for both control and test groups; the surrounding tissues were not subjected to any form of trauma. As such, the gross appearance of the surrounding tissues appeared to be of the same quality clinically, despite the increased fibroblast proliferation in the test group (as seen histologically at the first week of observation) [31-36].

Comparison of the size of the incisions show a significant difference in the decrease in size between both groups at the 1st week (p = 0.017), with the test group exhibiting a shorter incision 1 week post-operatively. A possible mechanism behind this is PHT’s stimulation of fibroblast proliferation with accompanying reduction of collagenase activity (Ghanpachi 2013). No differences were seen among the 2 groups at the 2nd and 4th week observation period since by that time, all the wounds have already healed superficially (i.e. clinically). Further analysis of the gross appearance of the incisions at the same observation periods reveals the same pattern. During the 1st week, all samples from the control group showed clinical signs of edema compared to the PHT group (p = 0.005) [37-42].

Conclusion

Within the limitations of this study, although there were initial differences in epithelialization, number of polymorphonuclear cells and fibroblasts, color, size and gross appearance, both groups displayed essentially the same features with regards to their wound healing capacities after 4 weeks. Within this context, a single application of 1% topical phenytoin shows improved efficacy on wound healing.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Smith PC, Cáceres M, Martínez A, Oyarzún A, Martínez J (2015) Gingival Wound Healing an Essential Response Disturbed by Aging? J Dent Res 94(3): 395-402.

- Bishop A (2015) The importance of effective wound care.

- Mashhadane F, AM (2011) The Clinical Effect of Phenytoin on Oral Wound Department of Dental Basic, MSc (Lec) College of Dentistry, University of Mosul, Iraq.

- Parizi GAN, Mohammadi M, Seifsafari M (2012) Effect of topical phenytoin on creeping attachment of human gingiva: A pilot study JOHOE/Summer & Autumn 1(2).

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, et al. (2002) ibroblasts and Their Transformations: The Connective Tissue Cell Family. Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th edn).

- Aly MM (2007) Valuation of The Efficacy of Topical Phenytoin in Management of Different Types of Skin Ulcers El-Minia Med. Bull, 18(2).

- Anstead GM, Hart LM, Sunahara JF, Liter ME (1996) Phenytoin in wound healing. Ann Pharmacol 30(7-8): 768-775.

- Arya R, Gulati S, Kabra M, Sahu JK, Kalra V (2011) Folic acid supplementation prevents phenytoin-induced gingival overgrowth in children. Neurology 76(15): 1338-1343.

- Bhatia A, Prakash S (2004) Topical Phenytoin for wound Healing. Dermatol Online J10(1): 1-5.

- Bhatia A, Nanda S, Gupta U, Gupta S, Reddy BS (2004) Topical phenytoin suspension and normal saline in the treatment of leprosy trophic ulcers: a randomized, double‐blind, comparative study. J Dermatolog Treat 15(5): 321-327.

- Baharvand M, Mortazavi A, Mortazavi H, Yaseri M (2014) Re-evaluation of the first phenytoin paste healing effects on oral biopsy ulcers. Ann Med Health Sci Res 4(6): 858-862.

- Baharvand M, Sarrafi M, Alavi K, Jalali, Moghaddam E (2010) Efficacy of topical phenytoin on chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis; a pilot study. Daru 18(1): 46-50.

- Bhattacharya R, Xu F, Dong G, Li S, Tian C, et al. (2014) Effect of Bacteria on the Wound Healing Behavior of Oral Epithelial Cells. PLoS One 9(2): e89475.

- Carriel V, Garzón I, Alaminos M, Cornelissen M (2014) Histological assessment in peripheral nerve tissue engineering. Neural Regen Res 9(18): 1657-1660.

- Firmino F, De Almeida AMP, Silva RDJG, Alves GDS, Grandeiro DS, et al. (2014) Scientific production on the applicability of phenytoin in wound healing. Rev Esc Enferm USP 48(1): 166-173.

- Flanagan M (2003) Improving accuracy of wound measurement in clinical practice. Ostomy Wound Manage 49(10): 28-40.

- Gan L, Fagerholm P, Kim HJ (1999) Effect of Leukocytes on Corneal Cellular Proliferation and Wound Healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 40(3): 575-581.

- Hallmon WW, Rossmann JA (2000) The role of drugs in the pathogenesis of gingival overgrowth A collective review of current concepts. Periodontology 21: 176-96.

- Hasamnis AA, Mohanty BK, Muralikrishna, Patil S (2010) Evaluation of Wound Healing Effect of Topical Phenytoin on Excisional Wound in Albino Rats. J Young Pharm 2(1): 59-62.

- Hemmati AA, Forushani HM, Asgari HM (2014) Wound Healing Potential of Topical Amlodipine in Full Thickness Wound of Rabbit. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod 9(3): e15638.

- Kadkhodazadeh M, Khodadoustan A, Seif N, Reza Amid R (2012) Effects of 1% Topical Phenytoin Suspension on the Donor Site Pain and Wound Size after Free Gingival Grafts. Journal Dental School 29(5): 366-372.

- Kamalinejad A, Ibrahimov R (2013) Evaluation of a topical application containing Phenytoin and Solcoseryl on gingival surgical wound healing. Journal of Indian Dental Association 7(6).

- Kapoor R (2015) Phenytoin May Have Applications for Multiple Sclerosis, Neurology Advisor, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London.

- Lazarus GS, Cooper DM, Knighton DR, Margolis DJ, Percoraro RE, et al. (1994) Definitions and guidelines for assessment of wounds and evaluation of healing. Arch Dermatol 130(4): 489-93.

- Légaré JF, Oxner A, Heimrath O, Issekutz, T (2007) Infiltration of polymorphonuclear cells into the post-ischaemic myocardium is dependent on β2 and α4 integrins. Int J Exp Pathol 88(4): 291-300.

- Lodha SC, Lohiya ML, Vyas MCR, Sudha Bhandari, Goyal RR, Harsh MK (1991) Role of phenytoin in healing large abscess cavities. Br J Surg 78: 105-108.

- López N, Cervero S, Jiménez MJ, Sánchez JF (2014) Cellular Characterization of Wound Exudate as a Predictor of Wound Healing Phases. Wounds 26(4): 101-107.

- Mandal A (2016) What are Fibroblasts? News Medical Life Sciences.

- Mathew M, Dhillon MS, Nagi ON, Sen RK, Nada R (2006) The effect of local administration of phenytoin on fracture healing: an experimental study. Acta Orthop Belg 72(4): 467-473.

- Meena K, Mohan AV, Sharath B, Somayaji SN, Bairy KL (2011) Effect of topical phenytoin on burn wound healing in rats. Indian J Exp Biol 49(01): 56-59.

- Morgan N (2012) Measuring Wounds. Wound Care Advisory.

- Mullins M, Thomason SS, Legro M (2005) Monitoring pressure ulcer healing in persons with disabilities. Rehabil Nurs 30: 92-99.

- Pastar I, Stojadinovic O, Yin NC, Ramirez H, Nusbaum AG, et al. (2014) Epithelialization in Wound Healing: A Comprehensive Review. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 3(7): 445-464.

- Pharmacother, A (2001) Topical phenytoin treatment of stage II decubitus ulcers in the elderly.

- Rolls G (2016) Steps to Better Grossing. Leica Biosystems. Advancing Cancer Diagnostics Improving Lives.

- Rozenfeld H (2012) A clinical review of wound healing.

- Shafer WG (1961) Effect of Dilantin sodium on cell lines in tissue culture. Pro Soc Exp Biol Med 106: 694-696.

- Simşek G, Ciftci O, Karadag N, Karatas E, Kizilay A (2014) Effects of topical phenytoin on nasal wound healing after mechanical trauma: An experimental study.

- Simon APE, Meyers AD (2016) Skin Wound Healing.

- Shaw J, Hughes CM, Lagan KM, Stevenson MR, Irwin CR, et al. (2011) The effect of topical phenytoin on healing in diabetic foot ulcers: a randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med 28(10): 1154-1157.

- Subbanna PK, Margaret Shanti FX, George J, Tharion G, Neelakantan N, et al. (2007) Topical phenytoin solution for treating pressure ulcers: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Spinal Cord 45: 739-743.

- Steinberg AD (1981) Clinical management of phenytoin-induced gingival overgrowth in handicapped children. The American Academy of Pedodontics.

- Tauro LF, Shetty P, Dsouza NT, Sucharitha SMS (2013) A Comparative Study of Efficacy of Topical Phenytoin vs Conventional Wound Care in Diabetic Ulcers. International Journal of Molecular Science 3(8).

- Umeki H, Tokuyama R, Ide S, Okubo M, Tadokoro S, et al. (2014) Leptin Promotes Wound Healing in the Oral Mucosa.

- Wiksman LB, Solomonik I, Spira R, Tennenbaum T (2016) Novel Insights into Wound Healing Sequence of Events. Toxicol Pathol 35(6): 767-779.

- Younes AA, Younes NA, Badran DH (2006) Topical phenytoin ointment increases autograft acceptance in rats. Saudi Med J 27(7): 962-926.

-

Dr. Mehdi Honarparvar. Evaluation of a Topical Phenytoin on Gingival Wound Healing. On J Dent & Oral Health. 2(4): 2020. OJDOH. MS.ID.000545.

-

Polymorphonuclear cells, Fibroblast, Epithelialization, Wound healing, Controversial effects, Upper maxillary, Mucoadhesive paste, Phenomenon, Basal layer.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.