Case report

Case report

Radicular Cyst in a Child: A Potential Complication of Dental Trauma - A Case Report

Loubna Benkirane1*, Ayoub Bouaalam2, Mahamadou Konate3 and Samira El Arabi1

1*Pediatric Dentistry Department, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Hassan II University, Casablanca, Morocco

2Prosthodontics Department, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Hassan II University, Casablanca, Morocco

3Department of Oral Medicine and Oral Surgery, Mohamed VI University of Health Sciences, Casablanca, Morocco

Loubna Benkirane, Pediatric Dentistry Department, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Hassan II University, Casablanca, Morocco.

Received Date: May 23, 2025; Published Date: July 02, 2025

Abstract

Introduction: Radicular cysts are benign odontogenic tumors that typically arise as a result of chronic inflammatory stimuli, often linked to dental trauma or infection. Although they are less frequent than developmental cysts in children, they are not negligible and require appropriate management to prevent complications.

Case Report: A 13-year-old girl presented with an intraoral swelling in the anterior maxillary region. Clinical and radiological examination,

revealed a cyst associated with infected necrosis of tooth 21, which had a history of trauma 6 years prior.

Results: Cone beam computed tomography helped determine the dimensions and relationships of the lesion with surrounding structures,

facilitating surgical planning. Histological analysis confirmed the diagnosis of radicular cyst. Postoperative follow-up showed satisfactory mucosal

healing and progressive bone regeneration.

Discussion: Radicular cysts can be diagnosed late due to their slow and asymptomatic growth. This particularity is especially problematic

in prepubertal patients, where delayed diagnosis and intervention can lead to significant damage to bone height. In this context, it is essential to

adopt a personalized and rigorous approach to managing these cysts, taking into account the size of the lesion, its relationship with adjacent noble

structures, and patient cooperation.

Conclusion: Radicular cysts can be a potential complication of neglected or untreated dental trauma in children. Rapid post-traumatic

consultation, adequate management, and rigorous follow-up are essential to prevent these potentially serious complications..

Keywords: Radicular cyst, Dental trauma, Children, Adolescent, Histological diagnosis, Surgical management

Abbreviation:DCTC: Dental Consultation and Treatment Center, CBCT: Cone Beam Computed Tomography

Introduction

Radicular cysts, also known as apical periodontal cysts or periapical cysts, are benign odontogenic tumors presenting as pathological intra-osseous cavities lined with epithelium of odontogenic origin and containing liquid or semi-liquid material. They account for 52.3% to 68% of odontogenic cysts in adults and primarily affect the anterior region of the maxilla [1-5]. In children (0-15 years), they are less frequent than developmental cysts [6], but their occurrence is not negligible.

They are generally triggered by chronic inflammatory stimuli, often linked to advanced carious lesions or dental trauma, leading to the proliferation of Malassez epithelial remnants present in the periodontal ligament.

According to their nature, there are two types: true apical cysts with a closed cavity and pocket cysts, open to the root canals [7]. Their growth is usually slow and asymptomatic, and their discovery is often fortuitous during radiological examinations. They become symptomatic in case of acute inflammation or when they reach a significant size, which can complicate the prognosis and management of the patient.

This article presents a case of a radicular cyst occurring in a child following neglected trauma on tooth 21. We will describe in detail the diagnostic and therapeutic approach, highlighting evidencebased practices to manage this case. Finally, we will emphasize the importance of early detection, appropriate management, and rigorous follow-up of dental trauma in children.

Case Report

A 13-year-old girl presented to the pediatric dentistry department of the dental consultation and treatment center (DCTC) (affiliated with the Ibn Rochd University Hospital Center in Casablanca) for an anterior maxillary intraoral swelling that had appeared two weeks prior. The patient’s history did not reveal any previous pain or swelling in the same region. However, a history of trauma in the same region dating back six years was noted. The patient had recently consulted a dentist who referred her to the DCTC.

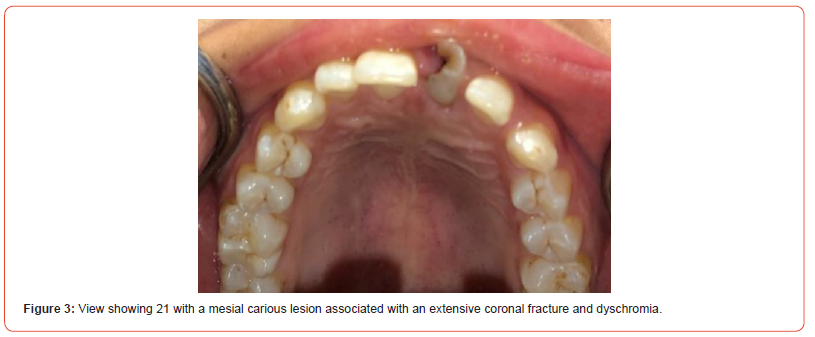

The extraoral examination did not show any visible swelling or facial asymmetry (Figure 1). Intraorally, no purulent discharge was observed. Upon palpation, a painless vestibular swelling, firm in consistency, non-fluctuant, and non-pulsatile, accompanied by a thinning of the external vestibular cortical bone in relation to tooth 21, was noted. This area was associated with inflammation and a gingival polyp (Figure 2). Oral hygiene was insufficient. Tooth 21 presented with a mesial carious lesion, an extended and complicated corono-radicular fracture, dyschromia, and mobility (Figures 3).

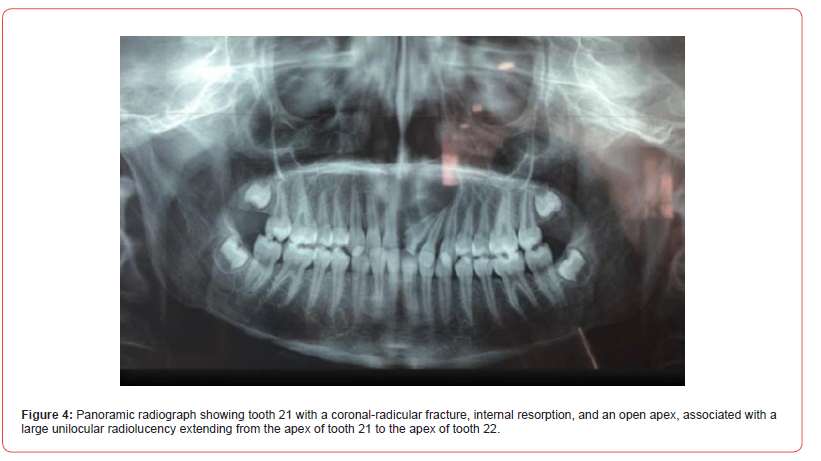

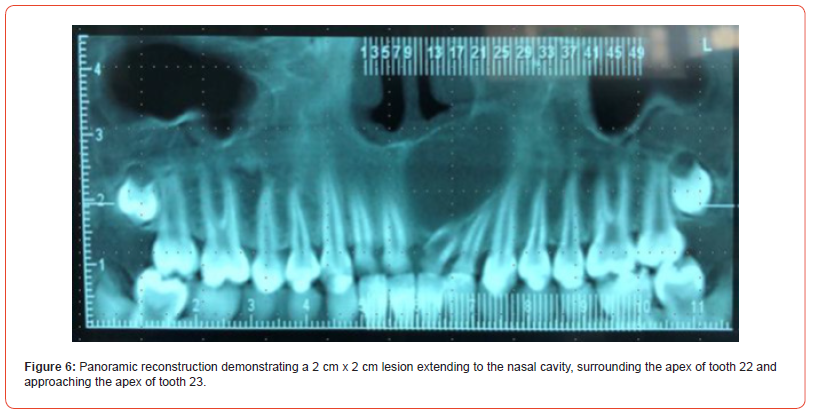

The orthopantomogram showed a significant deviation of tooth 21, an enlarged root canal with very thin walls over twothirds of the root, a juxtaosseous corono-radicular fracture, and an incompletely closed apex. A unilocular, oval, and supra-centimetric radiolucent image, associated with a well-defined radio-opaque border, encompassed the apex of tooth 21 and extended to the apex of tooth 22 (Figure 4).

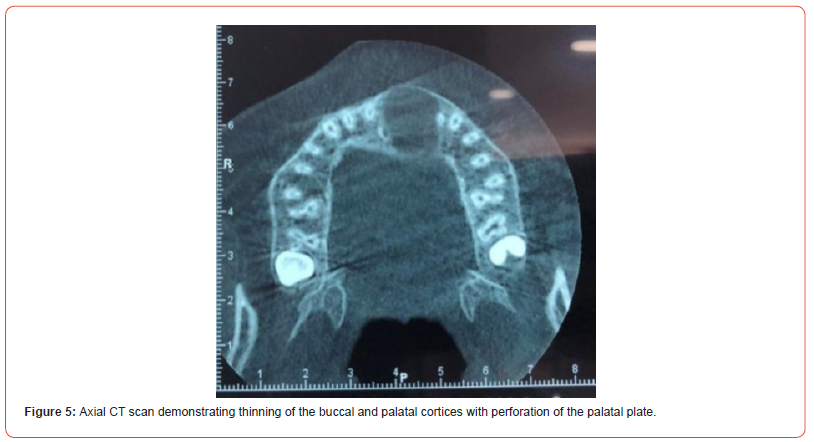

To determine the dimensions and relationships of the lesion with surrounding structures, cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) was indicated. The axial section revealed thinning of the vestibular and palatal bone tables, with maintenance of the continuity of the vestibular table but rupture of the palatal table (Figure 5). The panoramic section (Figure 6) highlighted a lesion measuring approximately 2cm x 2cm, extending upwards to the nasal cavity, encompassing and exceeding the apex of tooth 22 to approach that of tooth 23. Internal resorption of the root canal of tooth 21 was also observed.

Given the extent of the lesion, a cold sensitivity test was performed on tooth 22, which was negative. From a clinical and radiological point of view, the diagnostic hypotheses retained were an inflammatory odontogenic cyst of radicular type (lateral or apical), a paradental cyst, or a keratocyst. The definitive diagnosis could only be established after histological examination.

The presumptive diagnosis retained was a radicular cyst in the deformation phase, likely linked to chronic infected necrosis following untreated trauma occurring during immature permanent dentition.

After discussion with the patient and her parents, it was

decided to proceed with surgical enucleation of the cystic lesion

under local anesthesia. Antibiotic therapy was started the day

before the intervention and continued for 10 days. The treatment

consisted of enucleation of the cyst associated with extraction of

tooth 21, performed under local anesthesia. The operative steps

were as follows:

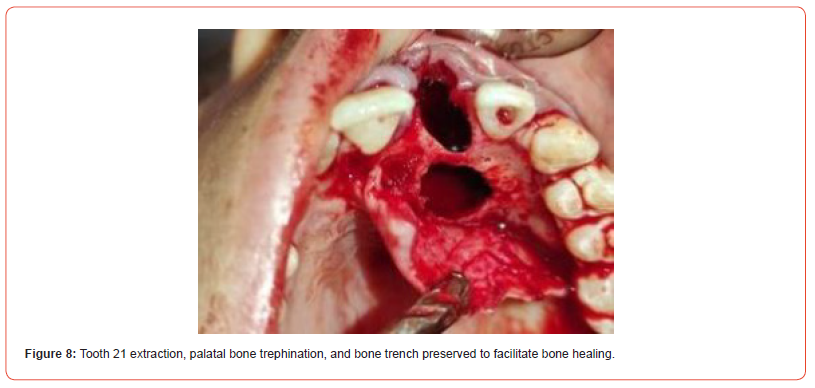

- Anesthesia targeting the incisive nerve.

- Intrasulcular mucoperiosteal incision from tooth 12 to 23

(Figure 7).

- Bone trephining through the palatal table to create access to

the cystic lesion.

- Extraction of tooth 21 to allow detachment and complete

enucleation of the Cyst.

A bone trench was left in place to support the flap and promote bone healing (Figure 8). Histological analysis revealed a cystic wall lined with stratified squamous epithelium and a dense inflammatory infiltrate, compatible with a radicular cyst.

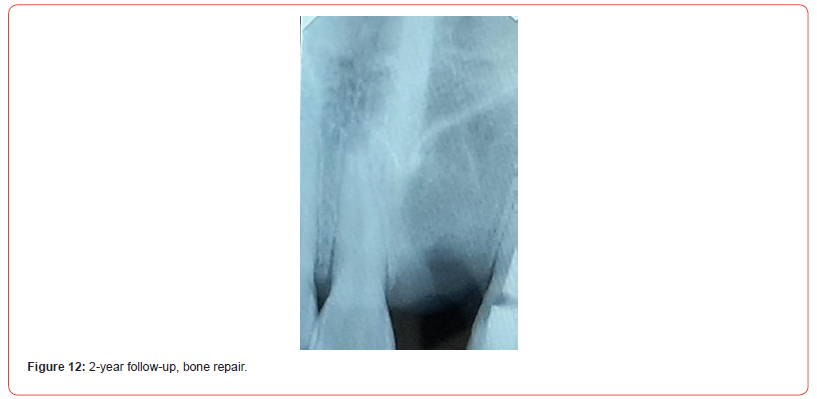

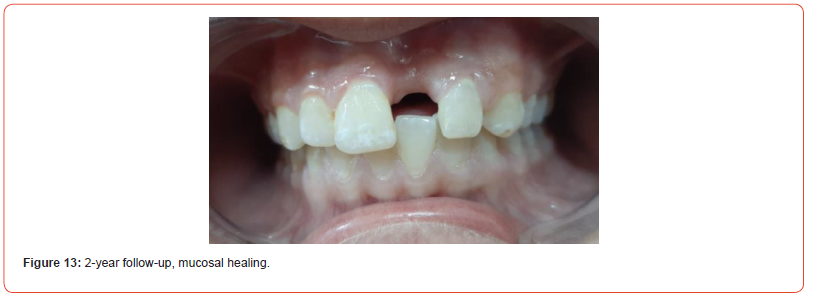

The postoperative follow-up showed satisfactory mucosal healing at 10 days, despite vestibular gingival collapse secondary to bone loss. The palatal bone trench had supported the palatal mucosa. For tooth 22, given the negative sensitivity test and trephining confirming the absence of pulp parenchyma, endodontic treatment with Gutta Percha was performed after canal decontamination with calcium hydroxide. A 4-month follow-up showed good mucosal healing (Figure 10). Clinical and radiological monitoring continued at 10 months (Figure 11) and 2 years, with repair and reconstitution of alveolar bone tissue filling the radiolucent image completely observed (Figures 12 and 13).

Discussion

Periradicular cystic lesions of endodontic origin are a common pathology in clinical practice, often discovered incidentally or after an acute infectious episode revealing a chronic inflammatory process that has been asymptomatic for a long time. The delay in diagnosis is a determining factor for the prognosis of healing.

During their evolution, radicular cysts, like all other jaw cysts,

go through four stages (8):

1. Latency phase: often asymptomatic. If signs of

desmodontitis do not alert the clinician, it is radiology of the

non-vital tooth that reveals the lesion. Painful phenomena only

occur with exacerbation of the inflammatory process.

2. Deformation phase: marked by a swelling of the external

table due to the progressive increase in cystic volume. The

overlying mucosa is generally of normal appearance (as in the

case of our patient).

3. Extrusion phase: clinically, a depressible mass is palpable.

It is fluctuant and painless. Puncture yields a clear yellow,

citrine, sometimes bloody, chocolate-brown liquid containing

cholesterol flakes.

4. Fistulization phase: the bone table is lysed, and only

the mucosa remains, which gradually thins until fistulization

occurs. The fistula discharges a serious or sero-hemorrhagic

fluid.

The initial radiographic diagnosis is generally based on an orthopantomogram revealing a unilocular radiolucent lesion bordered by a sclerotic cortex. When lesions increase in size, relationships of contiguity are established with the apices of neighboring roots, making it sometimes difficult to determine the apex of the causal tooth, which implies testing the sensitivity of all teeth in the region considered [9].

However, this type of image has limitations in precisely delimiting the lesion, justifying the use of more efficient volumetric examinations, such as cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), which allows better evaluation of the origin and extension of the lesion [10].

Although these examinations offer better evaluation of the lesion’s extension, their main limitation is exposure to a high dose of radiation. To put this into perspective, an intraoral radiograph exposes to an effective dose of less than 1.5μSv, while a panoramic radiograph exposes to a dose of 2.7 to 24.3μSv. CBCT investigations have doses that vary between 11-1073μSv depending on the area examined [11].

According to the American Association of Endodontists (AAE), CBCT should only be used when conventional low-dose imaging methods or other imaging modalities do not adequately answer the question posed [12].

Radiographically, inflammatory changes in periradicular tissues can be detectable as early as three months, but the time required for the lesion to fully develop and form a clear radiolucent image is variable and imprecise. According to estimates by Piette E, et al., a radicular cyst can grow at a rate of approximately 5 mm per year [13]. Radicular cysts, characterized by slow growth, generally do not reach very large dimensions [14]. However, the reported case illustrates an evolution over more than six years, explaining the significant size of the cystic cavity.

Cystic lesions have overlapping clinical and radiological aspects, which poses a diagnostic problem and makes it necessary to collect an anatomopathological diagnosis of the surgical specimen. Anatomopathologically, the radicular cyst is characterized by a stratified squamous epithelial lining whose thickness varies according to the degree of inflammation. The cyst wall is fibrous and often inflammatory, with immune cells and deposits of cholesterol and hemosiderin [15].

Regarding the therapeutic aspect, while surgery remains the standard for all developmental cysts, the literature agrees on the good response of radicular cysts to endodontic treatment, with a success rate of 85 to 90% [16]. In general, lesions smaller than 1 cm are treated conservatively with canal treatment, with a follow-up of at least one year before considering surgery in case of failure [17]. In contrast, the treatment of larger lesions is still debated. Some authors advocate for complete enucleation for cysts smaller than 3 cm [18, 19], while marsupialization, aimed at reducing the size of the lesion, is suggested for larger lesions. Despite its limitations, including the need for patient cooperation, non-compliance with endodontic treatment principles in terms of preventing bacterial contamination, and potential risks such as prolonged treatment duration, the need for two-stage surgery, and a theoretical risk of malignant transformation of the epithelium, this treatment modality deserves consideration [20], particularly in mixed dentition, where cystic pressure can lead to deviation of developing dental buds and, in some cases, inclusion of permanent teeth.

These conservative techniques of decompression or marsupialization, although effective in reducing the size of the lesion by relieving internal pressure, have a healing rate that remains difficult to estimate precisely. Complete enucleation of the cystic capsule remains the best therapeutic option when possible, offering a favorable prognosis and limiting risks, particularly malignant transformation of residual cystic cells. The cystic wall is separated from its internal bone surface and removed, allowing the cavity to fill with blood clot.

According to Yim and Lee [21], healing time varies according to the size of the lesion. A bone defect smaller than 30 mm will heal in approximately 12 months, while bone losses greater than 30mm can take 24 months to regenerate. Children have a superior regeneration potential compared to adults, offering faster and better-quality healing. A mucoperiosteal flap repositioned on solid banks associated with antibiotic treatment allows physiological organization of the blood clot and its transformation into stable bone tissue.

For the patient, enucleation avoided potential complications such as extension to the nasal floor or maxillary sinus without requiring general anesthesia. Additionally, the poor condition of tooth 21, characterized by an extended corono-radicular fracture, infection, tooth mobility, and very thin radicular walls, justified extraction. However, performing this extraction during puberty on bone already weakened by a cyst increases the risk of bone collapse due to active bone growth and remodeling at this age, which is precisely the case for our patient.

Finally, it is essential to recall the major distinction between true cysts and pseudocysts. The latter, communicating with the radicular apex, may sometimes not respond to adequate endodontic treatment, while true periapical cysts, isolated from the radicular canal, generally require surgical management [22].

The choice of treatment should be guided by several factors, including the extension of the lesion, its relationship with adjacent noble structures, the origin and clinical characteristics of the lesion, as well as patient cooperation and general condition. Furthermore, verifying the pulp status of teeth bordering the cyst and ensuring rigorous follow-up are essential to guarantee complete healing.

Conclusion

In conclusion, radicular cysts can be potential complications of neglected or untreated dental trauma occurring in immature permanent teeth. Infection can evolve insidiously, with a clinical examination often being non-specific, highlighting the importance of radiology in discovery and therapeutic planning. The definitive diagnosis is based on anatomopathological data. The management of radicular cysts requires a personalized and rigorous approach, taking into account several key factors, particularly in children. Rapid post-traumatic consultation, adequate management, and rigorous follow-up are essential to prevent these potentially serious complications.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Bouaalam for his significant contribution to the patient’s management and for his valuable input in drafting this article. We also extend our gratitude to Dr. Konate for performing the cystic enucleation surgery. Special thanks to the patient and her parents for their excellent adherence to care despite the remote location of their residence. We would also like to express our sincere gratitude to Pr El Arabi, Head of the Pediatric Dentistry Department, for his review of the article’s draft.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest or financial interest related to this article.

References

- Shear M, Speight P (2007) Cysts of the Oral Regions, Wright, Bristol, UK, 4th

- Killey HC, L W Kay, GR Seward (1977) Benign Cystic Lesions of the Jaws, Their Diagnosis and Treatment. (3rd) Edinburgh; New York: Churchill Livingstone; New York: distributed in U. S. by Longman.

- Regezi JA, Sciubba, J Oral Pathology (2016) Clinical Pathologic Correlations, (7th).

- Philip Sapp J, Wysocki GP, Eversole LR (2004) Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Elsevier (2nd).

- De Souza LB, Gordon Nunez MA, Nonaka CF, de Medeiros MC, Torres TF, et al. (2010) Odontogenic cysts: demographic profile in a Brazilian population over a 38-year period. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 15(4): e583-590.

- Serra VG, Conde DM, Marques RVCF, Freitas CVS, Lopes FF, et al. (2012) Odontogenic cysts in children and adolescents: A 21-year retrospective study. Brazilian Journal of Oral Sciences 11(2): 81-83.

- Nair PN (1998) New perspectives on radicular cysts: do they heal? Int Endod J 31(3): 155-160.

- Le Breton G (1998) Treatise on semiology and odonto-stomatological clinic Paris: CAP.

- Lasfargues JJ (2001) Clinical diagnosis of apical periodontitis. Clinical realities 12(2):149-62

- Ferreira Junior O, Damante JH, Lauris JR (2004) Simple bone cyst versus odontogenic keratocyst: differential diagnosis by digitized panoramic radiography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 33(6): 373-378.

- Allison JR, Garlington G (2017) The Value of Cone Beam Computed Tomography in the Management of Dentigerous Cysts - A Review and Case Report. Dent Update 44(3): 182-184, 186-188.

- American Association of Endodontists; American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology. (2011) Use of cone-beam computed tomography in endodontics Joint Position Statement of the American Association of Endodontists and the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 111(2): 234-237.

- Piette E, Reychler H (1991) Traite de pathologies buccale et maxillo-faciale. De Boeck Universite.

- El Ouarti I, Sakout M, Abdallaoui F (2019) Periradicular lesions of endodontic origin: Diagnostic and therapeutic issues. African journal of dentistry and implantology. Journal of dental medicine No15: 55-66

- Benyahya I, Bouachrine F (2002) Clinical and pathological aspects of odontogenic cysts. Dentist's Mail January 16-22.

- Kammer PV, Mello FW, Rivero ERC (2020) Comparative analysis between developmental and inflammatory odontogenic cysts: retrospective study and literature review. OMS 24(1): 73-84.

- Torres Lagares D, Segura Egea JJ, Rodríguez Caballero A, Llamas Carreras JM, Gutierrez Perez JL (2011) Treatment of a large maxillary cyst with marsupialization, decompression, surgical endodontic therapy and enucleation. J Can Dent Assoc 77: b87.

- Sauveur G, Ferkdadji L, Gilbert E, Mesbah M (2006) Maxillary cysts. EMC - Odonto-Stomatology 22-062-G-10.

- Ramachandra P, Maligi P, Raghuveer H (2011) A cumulative analysis of odontogenic cysts from major dental institutions of Bangalore city: A study of 252 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 15(1): 1-5.

- Martin SA (2007) Conventional endodontic therapy of upper central incisor combined with cyst decompression: a case report. J Endod 33(6): 753-757.

- David S (2017) Therapeutics of maxillary odontogenic cysts with intra-sinus extension (Doctoral thesis in dental surgery - Denis Diderot University) - Paris 7. N°5133/2017.

- Nair PN, Sundqvist G, Sjogren U (2008) Experimental evidence supports the abscess theory of development of radicular cysts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 106(2): 294-303.

-

Loubna Benkirane*, Ayoub Bouaalam, Mahamadou Konate and Samira El Arabi. Radicular Cyst in a Child: A Potential Complication of Dental Trauma - A Case Report. On J Dent & Oral Health. 9(1): 2025. OJDOH.MS.ID.000703.

-

Dental trauma, Odontogenic tumors, Anterior maxillary region, Periodontal cysts, Tooth, Extraction of tooth, Gingival collapse, Inflammatory process, Computed tomography, Cavity

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.