Research Article

Research Article

Determinants of Health-Related Quality of Life among Black Individuals with Low-Incomes, Excess Weight, and Comorbid Chronic Conditions

Carolyn M. Tucker1*, Kirsten Klein1, Lakeshia Cousin2, Kelly Folsom3, Shruti Kolli3, Juanita Miles Hamilton4 and Guillermo M Wippold5

1Department of Psychology, University of Florida, USA

2College of Nursing, University of Florida, USA

3College of Medicine, University of Florida, USA

4UF Health Cancer Center’s Community Partnered Cancer Disparities Research Collaborative, University of Florida, USA

5Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina, USA

Carolyn M Tucker, Department of Psychology, University of Florida, USA.

Received Date: August 23, 2024; Published Date: September 24, 2024

Abstract

Purpose: Black adults experience low health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Formative research is urgently needed to inform the development and implementation of tailored interventions to improve HRQoL among Black adults, particularly those with low incomes and chronic health conditions. The current study examined literature-derived socio-behavioral predictors of HRQoL among Black adults with low-incomes, multiple chronic conditions, and who have overweight/obesity.

Design: Cross-sectional design.

Setting: Participants were recruited at four Black/African American congregations.

Subjects: Participants were 243 Black adults with a mean age of 63.10 and the majority with household incomes below $50,000.

Measures: Demographic Questionnaire, Strain Questionnaire (to assess forms of stress), Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (to assess depression), Health-Promoting Lifestyles Profile II (to assess engagement in healthy eating and physical activity), World Health Organization Quality of Life (to assess HRQoL), and height/weight.

Analysis: Linear regressions using least squares estimation.

Results: Levels of engagement in physical activity (β = .257, p < 0.001), physical stress (β = -.311, p < 0.001), and depression (β = -.261, p < 0.001) were significant predictors of physical HRQoL. Depression (β = -.182, p < 0.05) was a significant predictor of psychological HRQoL.

Conclusion: The present study highlights strategies to promote HRQoL among these Black adults. Efforts based on such strategies may curb the impact of low HRQoL on premature morality and promote health equity.

Keywords: health-related quality of life; well-being; Black; African American; adults; low-income; social determinants of health

Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a multidimensional and subjective indicator of an individual’s physical, psychological, and social well-being [1,2]. This indicator of health has been a target of international and national public health campaigns since the 1990s [3]. That is because this indicator of health is strongly associated with premature mortality [4,5] and small improvements in HRQoL have been associated with meaningful health improvements [6]. Although efforts to improve HRQoL are needed, it is recommended that such efforts are population-specific and recognize the unique social determinants of health experienced by the priority population [7,8]. Thus, such efforts should be based on formative research among, and in partnership, with members of the priority population [9].

Disparities in Health and Well-Being

There are well-documented disparities in HRQoL. Surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that Black adults in the United States (US) have among the lowest HRQoL of any racial/ethnic group in the US [1]. This is reflected in the lower life expectancy of Black adults – these adults live 12.1 years less than their Asian counterparts, 5.9 years less than their White counterparts, and 6.4 years less than their Hispanic counterparts [10]. For many Black adults, the risk of low HRQoL on premature morality is compounded by the fact that individuals with low-incomes and those with chronic health conditions (e.g., overweight/obesity) are particularly at-risk for low HRQoL [11,12]. This is alarming because it is estimated that greater than 60% of non-Hispanic Black adults will have at least one chronic condition in the by 2050 [13]. Furthermore, currently, nearly 1 in 2 Black adults (48.6%) have a body mass index (BMI) of 30kg/m2 or greater [14] and 18.8% live in poverty [15]. Research indicates that there is a strong negative impact of chronic health conditions and socioeconomic status on HRQoL [16]. Despite the increase risk of adverse HRQoL among Black adults in the US, few interventions have been developed and implemented to improve this indicator of health [17].

Mechanisms Creating and Maintaining These Disparities

There are systemic mechanisms (e.g., discriminatory practices) that create and maintain these racial and socioeconomic disparities in health and well-being. For example, systemic discriminatory practices shape and maintain the social determinants of health that are known to impact HRQoL [18]. It is well established that marginalized communities, such as those who are Black and have low-incomes, experience adverse social determinants of health (e.g., access to health food otions, poorer interactions with health care services, limited opportunities for financial security) that result in poor health outcomes [19-21]. For example, these social determinants of health are associated with adverse mental health outcomes (e.g., stress, depression), [22] adverse physical health outcomes (e.g., increased body mass index), [23] and fewer opportunities to engage in health promoting behaviors (e.g., engagement in healthy eating and physical activity) [24]. With that being the case, it is unclear whether these mechanisms impact HRQoL among Black communities, though the impact of social determinants of health and adverse mental health on HRQoL has been found among Black adults [25,26].

Health Promotion among Black Communities

It is important to understand mechanisms that impact HRQoL among Black communities because not only do individuals from these communities endorse low HRQoL and experience high rates of premature mortality, but there are well-documented difficulties recruiting, retaining, and producing meaningful healthrelated changes among Black adults [9]. That is because few health promotion programs are tailored to the individual values, preferences, and perspectives of Black communities [9,27]. Health promotion efforts among Black adults have been criticized for being too narrow in scope and focusing on unidimensional indicators of health [28]. There is robust evidence indicating that Black adults have holistic conceptualization of health [29-31] – one that aligns well with the multidimensional nature of HRQoL. Thus, developing and implementing a health promotion program among Black adults that addresses multidimensional health is likely to recruit, retain, and produce meaningful health-related changes, ultimately decreasing premature mortality rates among these individuals.

Purpose of the Present Study

Although the need to develop and implement such an intervention is needed, there has been limited research exploring physical and psychological HRQoL in Black communities [17,25,32,33]. The present study is rooted in the biopsychosocial model of health [34]. This study seeks to understand the impact of health outcomes experienced by Black adults with low-incomes on HRQoL and at least one chronic health condition in addition to being overweight/obese. Specifically, the current study examines levels of stress (i.e., behavioral stress, physical stress, and cognitive stress), depression, engagement in healthy eating, engagement in physical activity, and BMI as predictors of physical HRQoL and psychological HRQoL among a sample of Black adults with low-incomes who have multiple chronic conditions that include overweight or obesity and at least one other chronic condition. An enhanced understanding of the socio-behavioral factors in HROL among multiply marginalized communities can aid in the creation and implementation of culturally sensitive health promotion interventions in these communities [35].

Method Participants

A total of 243 participants living in a mostly low-income Black community within a small city located in the Southeastern region of the United States participated in the study. Inclusion criteria for study participants were the following: (a) self-identifying as Black/American, (b) being ages 40 years or older, and (c) being able to communicate in English. Additionally, participants must have had overweight (BMI of 25kg/m2 to 29.9kg/m2) or obesity (BMI of 30kg/m2 or greater) and at least one of the following chronic conditions: (a) regularly smoke cigarettes, (b) regularly consume alcohol, (c) is a cancer survivor, and/or (c) at-risk for cancer because of having at least one close relative (i.e., mother, father, grandmother, grandfather, sister, or brother) who is a cancer survivor or has died from cancer to qualify for the present study. The status for each of these chronic conditions was self-reported; however, overweight or obesity were assessed using BMI scores, which were calculated based on measured height and weight.

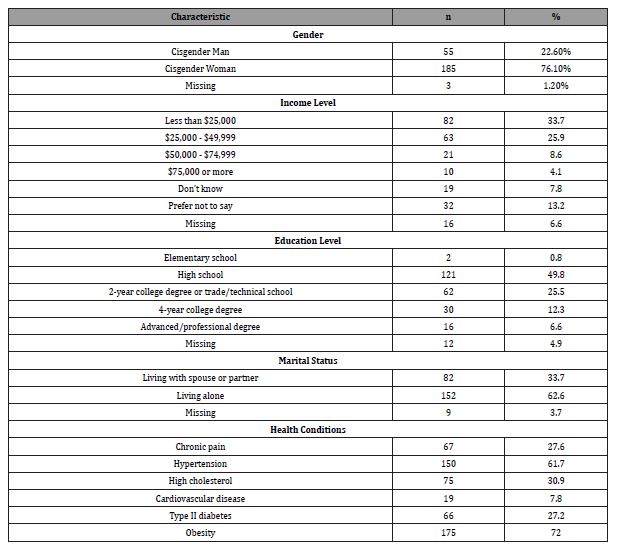

The age of participants ranged from 40 years to 88 years old (M = 63.10, SD = 10.25). Most of the participants (76.1%) identified as women. All participants identified as cisgender. Almost two-thirds of participants (62.6%) reported living alone rather than living with a spouse or partner. Many participants (49.8%) reported having completed high school as their highest level of education. Onethird of participants (33.7%) reported household incomes of less than $25,000 per year. Participants’ BMI ranged from 25kg/m2 to 66.5kg/m2 (M = 34.6, SD = 6.57). The majority of participants were classified as having obesity (72%), while the remaining participants were classified as overweight (28%). Many participants reported having chronic conditions that were not among those listed as study participation criteria, including chronic pain (27.6%), high blood pressure (61.7%), high cholesterol (30.9%), type 2 diabetes (27.2%) or cardiovascular disease (7.8%). See Table 1 for further participant description information.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of sample (N = 243).

Measures

All study participants completed an assessment battery. Below is the name and description of each questionnaire constituting this battery.

Demographic and Health Information Questionnaire (DHIQ): The DHIQ is a 43-item questionnaire developed by our study researchers to assess sociodemographic information including gender, age, annual household income, household size, and marital status. The questionnaire also types of chronic conditions.

Strain Questionnaire (SQ): [36] This 48-item questionnaire is utilized to measure participant’s overall levels of self-reported stress. The SQ has three subscales: behavioral, cognitive, and physical stress. It utilizes a 5-point Likert scale based on days/ weeks that participants experience the specified symptoms: Not at all (0 days), rarely (1–2 days), sometimes (3-4 days), frequently (5-6 days), and every day (7 days). The instruction on the SQ is to use the provided scale to rate the frequency of stress-related symptoms in the past week. Examples of these symptoms include backaches, nausea or upset stomach, headaches, and feelings of unreality. The SQ has been shown to have good internal consistency in diverse populations [37,38].

Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ): [39] The PHQ is an 8-item questionnaire used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms over the past two weeks. Higher scores indicate higher levels of depressive symptoms. Items correlate with DSM criteria for diagnosing a major depressive disorder. Participants respond to each item on a 4-point Likert scale from; Not at all, several days, more than half the days, and nearly every day. Examples of these items include poor appetite or overeating, little interest or pleasure in doing things, and feeling tired or having little energy. The PHQ has been utilized in Black populations [40,41].

Health-Promoting Lifestyles Profile II (HPLP-II): [42] The HLPLP-II is a 52-item inventory that measures participant’s engagement in health promoting lifestyle behaviors. This inventory assesses items across six subscales: spiritual growth, health responsibility, physical activity, nutrition, interpersonal relations, and stress management; however, the present study only utilized the physical activity and nutrition (healthy eating) subscales. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale from; Never, sometimes, often, and routinely. Sample items include: “How often do you eat 6-11 servings of bread, cereal, rice and pasta each day? and “How often do you follow a planned exercise program?”.

World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief Form (WHOQOL-BREF): [43] The WHOQOL-BREF is a 13-item questionnaire used to assess self-reported quality of life, defined by the WHO as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the cultural and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns”. There are four subscales: psychological health, physical health, social relations and environment. For the purpose of this study, only the physical health and psychological health related quality of life subscales were utilized. Responses to subscale items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from with the following scale ratings: Not at all, a little, a moderate amount, very much, and an extreme amount. Sample items include: “How much do you enjoy life?” and “How well are you able to get around?”.

Height and Weight Measurement: Each participant’s height and weight were measured in-person by the data enrollment team at specific enrollment sites. Height was collected in feet using a standard height rod, while weight was measured in pounds using a clinical weight measurement scale.

Procedure

Recruitment and Training of the Study Staff: The principal investigator and her university research team received study approval from the Institutional Review Board at the university where the principal investigator works. This study was part of a larger study that focused on physical and mental health status and health-related knowledge among Black adults living in a mostly low-income community. The study was conducted at four churches located in the low-income, primarily Black areas of a small city in the southeastern United States. The pastor and a member at each of these churches served as a pastor scientist and community scientist. These individuals and the university researchers formed the study team, and all members of this study team participated in training by the university researchers on participant recruitment and enrollment and data collection procedures. The university researchers also trained the pastor scientists/community scientists only to use iPads for data entry and data storage on REDCap (i.e., a protected data storage system at the university where the principal investigator works). Weekly meetings were held for all study staff to discuss study progress and related questions.

Participant Recruitment, Enrollment and Data Collection: Once the community scientists/pastor scientists were trained, recruitment of participants began. IRB-approved participant recruitment flyers were disseminated at various community events and locations (e.g., the four churches where the study was conducted and other local churches in the same areas as these churches, barber shops and community centers). Participants were also recruited in-person by the community scientists at local businesses, supermarkets, and churches. Pastor scientists disseminated information about the study via their social media and encouraged their congregants to talk with their community scientists about enrolling in the study. The snowball recruitment method ensued, which involves asking enrolled participants to disseminate flyers about the study to their peers. Interested individuals contacted study staff via a phone number listed on the recruitment flyer. Once community scientists verified via this phone call that the interested individual met inclusion criteria, an in-person enrollment meeting was scheduled.

Participants were able to choose the time and location of their enrollment and data collection appointment at their preferred data collection site. These data collection sites included the four participating churches and the principal investigator’s research lab—an enrollment site where a community scientist came to enroll participants who preferred this site. Each community scientist was provided with an iPad and cleaning materials to facilitate safe and efficient participant enrollments and collections.

At the enrollment and data collections appointments, community scientists reviewed and discussed informed consent with the telephone-prescreened potential study participants. Once participants signed study informed consent forms, their height and weight were measured and recorded. Participants then completed the earlier described assessment battery, which took 1-2 hours to complete. Participants were provided with the option to complete this assessment battery in-person via iPad or remotely via a REDCap survey link that was provided by the community scientist. To minimize respondent fatigue, all participants were encouraged to take 10-minute breaks after each 30 minutes of completing parts of the assessment battery. After completion of the assessment battery, participants were thanked for study participation and given a $60 Visa debit card for their participation time.

Results

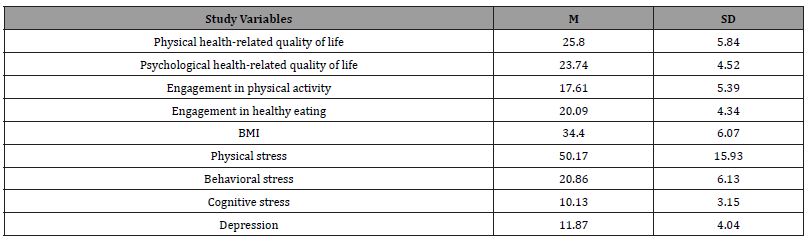

The data were first inspected for outliers. Scores greater than |3| standard deviations were deemed outliers and were then removed. Next, data were inspected for excessive skewness and kurtosis. Following this inspection, data were Blom transformed. Finally, the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance values were examined to assess potential multicollinearity. These values were deemed appropriate (i.e., VIF < 10; tolerance > 0.2)[44-46].See Table 2 for means and standard deviations of the study variables. Two linear multiple regressions were conducted to address the aims of this study.

Table 2: Means and standard deviations of study variables.

A linear multiple regression was conducted with BMI, depression, behavioral stress, physical stress, cognitive stress, engagement in healthy eating, and engagement in physical activity as predictor variables. The criterion variable was physical healthrelated quality of life. Overall, the predictors significantly predicted physical health-related quality of life, F (7, 219) = 31.178, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.48. Specifically, BMI (β = -.140, p < 0.01), engagement in physical activity (β = .257, p < 0.001), physical stress (β = -.311, p < 0.001), and depression (β = -.261, p < 0.001) were statistically significant predictors of physical health-related quality of life. Engagement in healthy eating (p = 0.430), behavioral stress (p = 0.077), and cognitive stress (p = 0.750) were not statistically significant predictors of physical health-related quality of life.

A linear multiple regression was conducted with BMI, depression, behavioral stress, physical stress, cognitive stress, engagement in healthy eating, and engagement in physical activity as predictors variables. The criterion variable was psychological health-related quality of life. Overall, the predictors significantly predicted psychological health-related quality of life, F (7, 220) = 8.062, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.28. However, only depression (β = -.182, p < 0.05) was a statistically significant predictor of psychological health-related quality of life. BMI (p = .434), engagement in physical activity (p = 0.273), engagement in healthy eating (p = 0.094), physical stress (p = 0.851), behavioral stress (p = 0.203), and cognitive stress (p = 0.080) were not statistically significant predictors of psychological health-related quality of life.

Discussion

Black adults experience low HRQoL – an indicator of health strongly associated with premature mortality [5]. The risk is compounded for Black adults who are living with low-incomes, have overweight/obesity, and have other chronic health conditions. Guidance from national and international organizations indicate that efforts to promote HRQoL should be tailored for the priority community [7]. Such tailoring should be based on formative research. The present study identified mechanisms that are associated with HRQoL among Black adults living with low-incomes and at least one chronic health conditions. The mechanisms identified in the present study can be the target of tailored intervention efforts to promote HRQoL among these Black adults – a group at-risk for low HRQoL.

The results of the current study indicate that lower levels of BMI, physical stress, and depression, and higher engagement in physical activity were found to be significantly associated with improved physical HRQoL, and lower depression was found to be significantly associated with increased psychological HRQoL. These findings highlight the importance of modifiable socio-behavioral factors that influence HRQoL among Black adults with obesity or who are overweight, have a chronic health condition, and who have low-incomes. Such modifiable variables can serve as the targets for interventions to improve HRQoL among these adults.

There is evidence linking stress, depression, and engagement in physical activity to HRQoL among Black men [26]. The results from the present study confirm this previous finding among a genderdiverse sample of Black adults who are overweight, have lowincomes, and are living with at least one chronic health condition. The present study builds on this previous study and contributes to the literature in two important ways: (1) the previous study found a significant association of perceived stress on HRQoL, whereas this study found a significant association of physical stress on physical HRQoL; and (2) the previous study was conducted among an internet-recruited sample of Black men, whereas this study was conducted among a community-based sample. These findings contribute to a nuanced understanding of promoting HRQoL among Black adults.

Notably, engagement in healthy eating was not a significant predictor of HRQoL in the present findings despite other studies indicating that improving diet quality can reduce the risk of health concerns and should be considered in health promotion interventions [47]. Similar studies have also found that engagement in healthy eating is not a significant predictor of HRQoL among Black Americans [26]. Additionally, research is needed to understand the relationships between engagement in healthy eating and HRQoL among Black adults. It should be noted that the present study and previous studies have found a statistically non-signfiicant association between engagement in health eating and HRQoL among Black adults when using the HPLP measure. Thus, additional research should investigate if the statistically non-significant is an artifact of the measure used.

The results of the current study should be viewed in conjunction with its strengths and limitations. The strengths of this study include involvement of a sample of Black Adults who are overweight or have obesity, have low-incomes, and at least one other chronic condition—a sample underrepresented in HRQoL research and health research in general and historically difficult to recruit. Furthermore, examining socio-behavioral contributors to HRQoL in our study is needed as understanding of these contributors will help inform health promotion interventions that are culturally tailored to improve overall HRQoL in mostly lowincome Black communities [48]. Another strength of the present study is the examination of types of stress (physical, behavioral, and cognitive stress) rather than overall stress as a predictor of HRQoL. Doing so builds on previous research [25,26] and contributes to a nuanced understanding of the predictors of HRQoL among Black adults. Some limitations of the present study include the crosssectional design which produces data from which causality cannot be inferred. Additionally, the study sample consisted of volunteer rather than randomly selected participants from one mostly lowincome Black community, which may limit the generalizability of the findings in this study. The reports from the demographic questionnaire indicating that 76.1% of the the study participants are cisgender females also limits the generalizability of the findings in this study to Black men.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study can inform strategies to promote HRQoL among Black adults with low incomes, who are overweight, and have at least one chronic health conditions. These adults are at-risk for low HRQoL – an indicator of health strongly associated with premature mortality [4,5]. Although efforts are urgently needed to promote HRQoL among these adults, such efforts must be based on formative research with the priority community. That is because health promotion efforts have welldocumented difficulties recruiting, retaining, and producing meaningful health-related changes among Black adults [9]. HRQoL is a conceptualization of health that is well-aligned with the holistic conceptualization of health endorsed by Black adults who have participating in focus group discussions [30]. These results have promising implications for efforts to promote health equity among Black adults with low incomes, who are overweight, and who have chronic health conditions – individuals who are at-risk for advese health outcomes.

Funding Statement

Carolyn Tucker received funding for this study from the University of Florida Health Cancer Center. Guillermo Wippold is funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (K23MD016123). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jonathan Licht, Director the University of Florida Health NCI Designated Cancer Center, for his strong support of this research.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Zack MM (2013) Health-related quality of life - United States, 2006 and 2010. MMWR Suppl 62(3): 105-111.

- Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM (1993) The rand 36‐item health survey 1.0. Health Economics 2(3): 217-227.

- Hennessy CH, Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Scherr PA, Brackbill R (1994) Measuring Health-Related Quality-of-Life for Public-Health Surveillance. Public Health Reports 109(5): 665-672.

- DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, He J, Muntner P (2006) Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question: A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 21(3): 267-275.

- Nevarez-Flores AG, Chappell KJ, Morgan VA, Neil AL (2023) Health-Related Quality of Life Scores and Values as Predictors of Mortality: A Scoping Review. J Gen Intern Med 38(15): 3389-3405.

- Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW (2003) Interpretation of Changes in Health-related Quality of Life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Medical Care 41(5): 582-592.

- Bakas T, McLennon SM, Carpenter JS, Buelow JM, Otte JL, et al. (2012) Systematic review of health-related quality of life models. Health Qual Life Outcomes 10: 134.

- Wilson IB, Cleary PD (1995) Linking Clinical Variables with Health-Related Quality of Life. JAMA 273(1): 59-65.

- Wippold GM, Frary SG, Abshire DA, Wilson DK (2021) Improving Recruitment, Retention, and Cultural Saliency of Health Promotion Efforts Targeting African American Men: A Scoping Review. Ann Behav Med 56(6): 605-619.

- Arias E, Xu J (2022) United States Life Tables 2020. Natl Vital Stat Rep 71(1): 1-64.

- Zhang S, Xiang W (2019) Income gradient in health-related quality of life — the role of social networking time. International Journal for Equity in Health 18(1): 44.

- Isobel TMH, Michelle LH, Mary FL, Timothy LF (2009) How do common chronic conditions affect health-related quality of life. British Journal of General Practice 59(568): e353-358.

- Ansah JP, Chiu CT (2022) Projecting the chronic disease burden among the adult population in the United States using a multi-state population model. Front Public Health 10: 1082183.

- Prevention CfDCa (2019) Normal weight, overweight, and obesity among adults aged 20 and over, by selected characteristics: United States, selected years 1988–1994 through 2015–2018.

- Bureau USC (2020) Poverty Rates for Blacks and Hispanics Reached Historic Lows in 2019.

- Wippold GM, Roncoroni J (2020) Hope and health-related quality of life among chronically ill uninsured/underinsured adults. Journal of Community Psychology 48(2): 576-589.

- Tucker CM, Wippold GM, Roncoroni J (2022) Impact of the Health-Smart Holistic Health Program: A CBPR Approach to Improve Health and Prevent Adverse Outcomes for Black Older Adults. Journal of Prevention and Health Promotion 3(4): 589-607.

- Hagan K, Javed Z, Cainzos-Achirica M, Hyder AA, Mossialos E, et al. (2023) Cumulative social disadvantage and health-related quality of life: national health interview survey 2013–2017. BMC Public Health 23(1): 1710.

- Feagin J, Bennefield Z (2014) Systemic racism and U.S. health care. Soc Sci Med 103: 7-14.

- Gravlee CC (2020) Systemic racism, chronic health inequities, and COVID-19: A syndemic in the making. Am J Hum Biol 32(5): e23482.

- Frieden TR (2015) CDC health disparities and inequalities report - United States, 2013. MMWR Suppl 62(3):1-2.

- Alegría M, NeMoyer A, Falgàs Bagué I, Wang Y, Alvarez K (2018) Social Determinants of Mental Health: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Curr Psychiatry Rep 20(11): 95.

- Braveman P, Gottlieb L (2014) The social determinants of health: it's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep 129(2): 19-31.

- Manderson L, Jewett S (2023) Risk, lifestyle and non-communicable diseases of poverty. Globalization and Health 19(1): 13.

- Wippold GM, Tucker CM, Roncoroni J, Henry MA (2021) Impact of Stress and Loneliness on Health-Related Quality of Life Among Low Income Senior African Americans. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 8(4):1089-1097.

- Wippold GM, Frary SG (2022) Predictors of Health-Related Quality of Life Among African American Men. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 9(6): 2131-2138.

- Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL (1999) Cultural sensitivity in public health: Defined and demystified. Ethnicity and Disease 9(1):10-21.

- Gilbert KL, Ray R, Siddiqi A, et al. (2016) Visible and Invisible Trends in Black Men's Health: Pitfalls and Promises for Addressing Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Inequities in Health. Annual Review of Public Health 37:295-311.

- Hankerson SH, Suite D, Bailey RK (2015) Treatment disparities among African American men with depression: Implications for clinical practice. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 26(1):21-34.

- Griffith DM, Cornish EK, Bergner EM, Bruce MA, Beech BM (2018) "health is the Ability to Manage Yourself Without Help": How Older African American Men Define Health and Successful Aging. Journals of Gerontology - Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 73(2):240-247.

- Taylor TR, Mohammed A, Harrell JP, Makambi KH (2017) An examination of self-rated health among African-American men. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 4(3): 425-431.

- Wippold GM, Frary SG (2022) Predictors of Health-Related Quality of Life Among African American Men. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 9(6): 2131-2138.

- Wippold GM, Garcia KA, Frary SG (2023) The role of sense of community in improving the health-related quality of life among Black Americans. Journal of Community Psychology 51(1):251-269.

- Engel GL (1977) The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 196(4286): 129-136.

- Tucker CM, Arthur TA, Roncoroni J, Wall W, Sanchez J (2015) Patient-Centered, Culturally Sensitive Health Care. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 9(1): 63-77.

- Lefebvre RC, Sandford SL (1985) A multi-modal questionnaire for stress. Journal of Human Stress 11(2): 69-75.

- Tucker CM, Marsiske M, Rice KG, Nielson JJ, Herman K (2011) Patient-Centered Culturally Sensitive Health Care: Model Testing and Refinement. Health Psychology 30(3): 342-350.

- Brown SL, Schiraldi GR, Wrobleski PP (2009) Association of Eating Behaviors and Obesity with Psychosocial and Familial Influences. American Journal of Health Education 40(2): 80-89.

- Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, et al. (2009) The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord 114(1-3): 163-173.

- Huang FY, Chung H, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL (2006) Racial and ethnic differences in the relationship between depression severity and functional status. Psychiatr Serv 57(4): 498-503.

- Lee HY, Lee LH, Luo Y, et al. (2022) Anxiety and Depression amongst African-Americans Living in Rural Black Belt Areas of Alabama: Use of Social Determinants of Health Framework. The British Journal of Social Work 52(5): 2649-2668.

- Walker S, Sechrist K, Pender N (1995) Health Promotion Model - Instruments to Measure Health Promoting Lifestyle: Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile [HPLP II] (Adult Version). Journal of Nursing Research.

- World Health O. WHO (2012) QOL User Manual L.

- Myers RH (1990) Classical and Modern Regression with Applications. PWS-KENT.

- Bowerman BL, O'Connell RT (2000) Linear Statistical Models: An Applied Approach. Duxbury.

- Menard S (2002) Applied Logistic Regression Analysis. In: Thousand Oaks, California.

- Zhao Y, Araki T (2024) Diet quality and its associated factors among adults with overweight and obesity: findings from the 2015-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Br J Nutr 131(1): 134-142.

- Kauffman KS, Dosreis S, Ross M, Barnet B, Onukwugha E, et al. (2013) Engaging hard-to-reach patients in patient-centered outcomes research. J Comp Eff Res 2(3): 313-324.

-

Carolyn M. Tucker*, Kirsten Klein, Lakeshia Cousin, Kelly Folsom, Shruti Kolli, Juanita Miles Hamilton and Guillermo M Wippold. Determinants of Health-Related Quality of Life among Black Individuals with Low-Incomes, Excess Weight, and Comorbid Chronic Conditions. On J Cardio Res & Rep. 7(5): 2024. OJCRR.MS.ID.000675.

-

Angioplasty, PTCA, NSTE-ACS, LAD, Coronary syndrome, Heart, Drug-eluting

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.