Research Article

Research Article

Living Standards of 75 Hospitalized Black African Patients with Peripartum Cardiomyopathy. Study at Sikasso Hospital (Sikasso, Mali)

Traore-Kissima Abdoulaye1, Coulibaly Siaka1, Haidara Ousmane1, Cenac Arnaud2*, Cissouma Assetou3, Dembele Ahmadou4, Soumaila Alama Traore5 and Dade Ben Sidi Haidara6

1Department of Cardiology, Sikasso hospital, Mali

2UFR of Medicine, University of Western Brittany, France

3Pediatry Department, Sikasso hospital, Mali

4Department of Ear-Nose-Throat, Sikasso hospital, Mali

5Gynecology Department, Sikasso hospital, Mali

6Hospital Manager, Sikasso hospital, Mali

Cenac Arnaud, UFR of Medicine, University of Western Brittany, Brest, France.

Received Date:November 10, 2022; Published Date:November 23, 2022

Definition:Peripartum cardiomyopathy is the onset of heart failure with no identifiable cause within the last month of pregnancy or within 5

months after delivery.

Aims: To study the living standard of patients hospitalized with peripartum cardiomyopathy in Sikasso (Mali).

Method: Inclusion criteria: hospitalized patients with heart failure beginning during the last month of pregnancy or during the five months

after delivery, with echocardiography. Known prior heart disease is an exclusion criterion. The evaluation of the living standard is as follows: high,

medium, low. The notions of food satiety, intense work during pregnancy, level of schooling are the criteria. This information was obtained by personalized

interview in the language of the patients, with their oral agreement.

Results: From March 1, 2019 to February 28, 2021, 1144 patients were hospitalized in the Cardiology department of Sikasso hospital (Sikasso,

Mali). The diagnosis of heart failure was made in 456 patients (39.8%). Seventy-five (75) corresponded to the diagnosis of peripartum cardiomyopathy

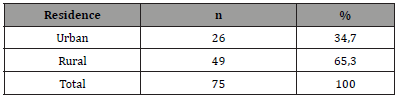

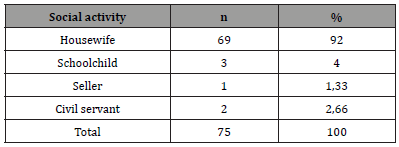

(6.6%). Two out of three patients (65.3%) were of rural origin. Four out of five (77.3%) had 2 or more deliveries at time of diagnosis. A very

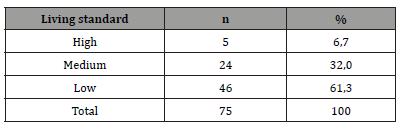

large majority (92.0%) were homemakers, without salary. The results of the living standard assessment are as follows: high = 6.7%, medium = 32%,

low = 61.3%.

Conclusion: A large majority of patients with peripartum cardiomyopathy have a low standard of living and belong to underprivileged social

classes. These results confirm identical facts previously reported in publications. The prevention of dilated cardiomyopathy must call upon an improvement

in the standard of living, in particular of African women living in rural areas.

Keywords:Peripartum cardiomyopathy; African woman; Living standard; Sikasso

Introduction

Peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is the onset of heart failure with no identifiable cause within the last month of pregnancy or within 5 months after delivery [1]. This cardiac disease is very rare in Europe [2, 3], less rare in the USA [4] and frequent in Africa, especially in West Africa, in the sudanese-sahelian area [5-7]. In a previous study, we discussed the living conditions of African women with PPCM [4]. The clinical experience of the authors allows them to affirm that these patients belong to underprivileged social classes. The aim of this study is to clarify the living standard of patients hospitalized with peripartum cardiomyopathy in Sikasso (Mali).

Patient and Method

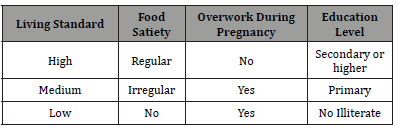

Inclusion criteria of patients: hospitalized African women with heart failure beginning during the last month of pregnancy or during the five months after delivery, with echocardiography. Known prior heart disease is an exclusion criterion. The evaluation of the living standard is as follows: high, medium, low. The notions of food satiety, intense work during pregnancy, level of schooling are the criteria (Table 1). These informations were obtained by personalized interview in the language of patients, with their oral agreement.

Table 1:Criteria used for evaluation of living standard.

Result

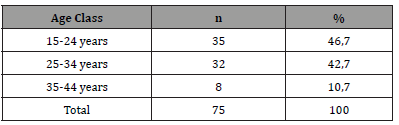

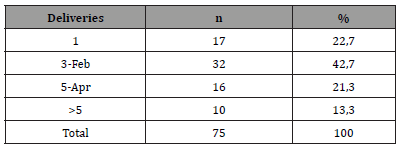

From March 1, 2019 to February 28, 2021, 1144 patients were hospitalized in the Cardiology department of Sikasso hospital (Sikasso, Mali). The diagnosis of heart failure was made in 456 patients (39.8%). Seventy-five (75/1144, 6.6%) corresponded to the diagnosis of peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM). Among them, a very large majority (67/75, 89.4%) were aged under 35 at diagnosis (Table 2). A minority of patients (17/75, 22.7%) developed PPCM during or after their first pregnancy (Table 3). Near four out of five (77.3%) had 2 or more deliveries at time of diagnosis. Two out of three patients (49/75, 65.3%) were of rural origin (Table 4). A very large majority (92.0%) were homewifes, without salary (Table 5). The results of the living standard assessment are as follows: high = 6.7% (5/75), medium = 32% (24/75), low = 61.3% (46/75) (Table 6)..

Table 2:Age class of patients with PPCM.

Table 3:Groups of patients according to the number of deliveries. (32+16+10=58/75 [77,3%] had more then 2 deliveries).

Table 4:Residence of patients.

Table 5:Social activity of patients.

Table 6:Standard living of patients with PPCM.

Discussion

CMPP is a frequent disease in Sudano-Sahelian Africa [4-8], whereas it is exceptional in European countries, particularly in France [2, 3]. A large African minority, originating from the Sudano- Sahelian world, lives in France “protected” from this pathology [4]. This fact prompted us to analyze the living conditions of the populations concerned in Mali. Knowing the standard of living of patients is an interesting step in understanding their daily experience. We chose the oral interview technique because most of these illiterate patients could only communicate orally in the vernacular. The questionnaire, simple, was organized in such a way that the answers are binary: yes or no. In a previous study [4] two of us (AC, ATK), analyzing data from the literature, showed that some of these patients lived in difficult conditions. But, in the publications analysed, the majority of the authors do not talk about the living conditions of the patients: a conclusion is therefore impossible. Our present work aims to fill this gap.

Our results (Tables) clearly indicate that in Sikasso, CMPP is almost always diagnosed in housewives (92%), with little or no schooling (93%), living in rural areas (65%), most often multiparous (77 % have had at least two previous deliveries). As for their age, 67/75, or almost 90%, are in the 15-35 age group. A low standard of living concerns 46/75 patients (table 6) or 61%: that is to say that almost two thirds of them do not eat enough, do heavy work throughout their pregnancy, and are illiterate. Patients with a “high” standard of living, according to our criteria, are very much in the minority (5/75 or 6.7%). These results support the hypothesis that PPCM is not a disease but a syndrome involving several more or less associated risk factors [9]. Pregnancy itself increases the work of the heart which must irrigate the placenta and fetus. These increases in work and flow peak at the end of pregnancy, during the weeks before delivery [10]. During delivery, cardiac output should quickly return to normal. Several factors, already present or in the process of setting up, and associated in different ways, will cause CMPP: climatic, hormonal, nutritional, auto-immune, infectious, inflammatory factors.

Climate

The effects of climate and heat have been detailed by Ford, et al. [6] in Zaria, northern Nigeria, where PPCM has a particularly high incidence. Parturients, installed on heated litters, absorb large quantities of natron. This Hausa tradition is found, in another form, among other ethnic groups in the region [8]. Seasonal variations in the incidence of new cases are described: during the rainy season (July to October), the number of new cases diagnosed doubles in Niamey (Niger) [8]. This hot and humid season causes peripheral vascular dilation and cardiac volume overload [8, 11-12].

Physical effort

Rural African women, following tradition, pound millet (a pestle weighs 15 kg), fetch water from the well and wood for the fire needed to prepare meals. In addition, they take care of young children and breastfeed. That is a major energy expenditure in a context of climatic heat immersion [11].

Hormones

The possible role of prolactin has been demonstrated experimentally in a mouse model of PPCM [13, 14]. The detrimental effect of prolactin results from the myocardial upregulation of cathepsin-D, which in turn cleaves prolactin into a 16 kDa fragment (vasoinhibin) with anti-angiogenic and pro-apoptotic properties altering the development of the system heart vascular.

Nutrition

Our results highlight the insufficiency of calorie intake in most of the 75 patients studied. Seventy (93%) do not experience daily satiety while preparing meals. A systematic increase in sodium intake (in the form of natron), in the postpartum period, is a tradition found among the Hausa and Djerma-Songhaï ethnic groups [6, 8]. She explains the frequent clinical pictures of anasarca observed during hospitalization. A case-control study in Niamey revealed lowered plasma albumin and pre-albumin in patients with PPCM [15], biological signs of protein malnutrition. Low plasma selenium, a sign of a deficiency in this essential trace element in the management of oxidative stress, has been described in case-control studies in Niamey, Niger [15, 16] and Bamako, Mali [17]. Such a result was not found in patients with PPCM in Cotonou [18].

Inflammation and autoimmunity

The hypothesis of myocarditis, often mentioned, has been proven by endomyocardial biopsies (EMB) revealing characteristic histological signs [19-22]. This concerns only a limited number of cases, in patients living in developed countries (where the practice of EMB is possible), with a social context different from that of the Sudano-Sahelian region of Africa. Autoimmune myocarditis, evoked on the argument of postpartum immunological rebound, was treated with immunosuppressants. Histological remission was achieved [19, 20]. But the systematic search for humoral signs of autoimmunity, carried out on patients from Niamey, by case-control study, was negative [23]. These contradictory facts led to the search for the responsibility of infectious agents.

Infection

Enteroviruses, suspected first, were ruled out by a case-control study [24]. Chlamydophila pneumoniae (Cpn), an intracellular infectious agent, has been studied in patients from Niamey [25]. In this case-control study, a statistical association IgA anti-Cpn was demonstrated between a group of patients with PPCM and a group of healthy African women who had recently given birth. These anti- Cpn IgA antibodies are in favor of an active infection. In addition, the rate of these antibodies observed at the time of diagnosis has a prognostic value: patients with the highest levels of anti-Cpn IgG and IgA have a more severe prognosis [26]. These facts are in favor of a role of Cpn in the genesis of the PPCM. Inflammation. If there is an infectious component during the PPCM, an inflammatory syndrome must accompany it and be extinguished in the event of remission. Such a scenario has been demonstrated by a study comparing the plasma level of NT-ProBNP (N-terminal-pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide), a biological sign of heart failure, and the ultrasensitive C-reactive protein (CRPus) (sign of inflammation). These 2 signs evolve in parallel: they normalize when the clinical signs disappear [27].

Conclusion

A low living standard is therefore a risk factor for PPCM in Sikasso because African women belonging to this group often combine the various factors described above: hot environment, physical work throughout pregnancy, food insufficiency, excessive intake sodium, intervention of prolactin on the myocardium during lactation, possibly autoimmune myocarditis or infectious recurrence due to Chlamydophila pneumoniae.

Preventive action can be proposed, by improving diet or limiting physical effort during pregnancy, being aware that this is an upheaval in the social order among mostly unschooled African women.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Pearson GD, Veille JC, Rahimtoola S, Hsia J, Oakley CM, et al. (2000) Peripartum cardiomyopathy: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Office of Rare Diseases (National Institutes of Health) workshop recommendations and review. JAMA 283(9): 1183-1188.

- Barrillon A, Batiste M, Grand A, Gay J, Gerbaux A (1978) Myocardiopathie de la grossesse chez la femme blanche. Arch Mal Cœur (Paris) 71: 406-413.

- Ferrière M, Sacrez A, Bouhour JB, Cassagnes J, Geslin P, et al. (1990) La myocardiopathie du péripartum: aspects actuels. Étude multicentrique: 11 observations. Arch Mal Cœur (Paris) 83: 1563-1569.

- Cenac A, Traore-Kissima A (2019) Yes, we can prevent peripartum cardiomyopathy, but. SL Clinical and Experimental Cardiology 2(1): 117.

- Cénac A, Mounio OM, Develoux M, Soumana I, Lamothe F, et al. (1985) Les cardiopathies de l’adulte à Niamey (Niger). Enquête épidémiologique prospective. A propos de 162 observations. Cardiol Trop 11: 125-134.

- Ford L, Abdullahi A, Anjorin FI, Danbauchi SS, Isa MS, et al. (1998) The outcome of peripartum cardiac failure in Zaria, Nigeria. Q J Med 91: 93-103.

- Cenac A, Djibo A (1998) Postpartum cardiac failure in sudanese-sahelian Africa. Clinical prevalence in Western Niger. Am J Trop Med Hyg 58: 319-323.

- Cénac A, Gaultier Y, Soumana I, Develoux M (1989) La myocardiopathie post-partum en région soudano-sahé Etudes clinique et épidémiologique de 66 cas. Arch Mal Cœur (Paris) 82: 553-558.

- Cénac A, Gaultier Y, Soumana I, Harouna Y (1990) La myocardiopathie dilatée péripartum : maladie ou syndrome? L’Information cardiologique 14: 779-786.

- Hunter S, Robson SC (1992) Adaptation of the maternal heart in pregnancy. Br Heart J 68(6): 540-543.

- Cenac A, Djibo A, Simonoff M, Diarra B, Toure K, et al. (2010) Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Results of 3 West Africa studies (Bamako, Cotonou, Niamey). First International Congress on Cardiac Problems in Pregnancy. Valencia pp. 25-28.

- Sanderson JE, Adesanya CO, Anjorin FI, Parry EHO (1979) Postpartum cardiac failure - heart failure due to volume overload? Am Heart J 97: 613-621.

- Denise Hilfiker-Kleiner, Karol Kaminski, Edith Podewski, Tomasz Bonda, Arnd Schaefer, et al. (2007) A cathepsin D-cleaved 16kDa form of prolactin mediates postpartum cardiomyopathy Cell 128(3): 589-600.

- Clapp C, Thebault S, Martinez de la Escalera G (2007) Hormones and postpartum cardiomyopathy. Trends Endocrinol Met 18: 329-330.

- Cenac A, Simonoff M, Djibo A (1996) Nutritional status and plasma trace-elements in peripartum cardiomyopathy. A comparative study in Niger. J Cardiovasc Risk 3: 483-487.

- Cenac A, Simonoff M, Moretto Ph, Djibo A (1992) A low plasma selenium is a risk factor for peripartum cardiomyopathy. A comparative study in Sahelian Africa. Int J Cardiol 36: 57-59.

- Cenac A, Diarra MB, Sanogo K, Sergeant C, Jobic Y, al. (2004) Plasma selenium and peripartum cardiomyopathy in Bamako (Mali). Méd Trop 64: 151-154.

- Cenac A, Sacca-Vehounkpe J, Poupon J, Dossou-Yovo-Akindes R, D’Almeida-Massougbodji M, et al. (2009) [Serum selenium and dilated cardiomyopathy in Cotonou, Benin]. Med Trop 69: 272-274.

- Melvin KR, Richardson PJ, Olsen EGJ, Daly K, Jackson G (1982) Peripartum cardiomyopathy due to myocarditis. N Engl J Med 307: 731-734.

- Midei MG, DeMent SH, Feldman AM, Hutchins GM, Baughman KL (1990) Peripartum myocarditis and cardiomyopathy. Circulation 81(3): 922-928.

- Rizeq MN, Rickenbacher PR, Fowler MB, Billingham ME (1994) Incidence of myocarditis in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 74: 474-477.

- Felker GM, Jaeger CJ, Klodas E, Thiemann DR, Hare JM, et al. (2000) Myocarditis and long-term survival in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J 140: 785-791.

- Cenac A, Beaufils H, Soumana I, Vetter JM, Devillechabrolle A, et al. (1990). Absence of humoral autoimmunity in peripartum cardiomyopathy. A comparative study in Niger. Int J Cardiol 26: 49-52.

- Cenac A, Gaultier Y, Devillechabrolle A, Moulias R (1988) Enterovirus infection in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Lancet 2: 968-969.

- Cénac A, Djibo A, Sueur JM, Chaigneau C, Orfila J (2000) Infection à Chlamydia et cardiomyopathie dilatée péripartum à Niamey (Niger). Méd Trop 60: 137-140.

- Cenac A, Djibo A, Velmans N, Sueur JM, Chaigneau C, et al. (2003) Are anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae antibodies prognosis indicators for peripartum cardiomyopathy? J Cardiovasc Risk 10: 195-199.

- Cenac A, Tourmen Y, Adehossi E, Couchouron N, Djibo A, et al. (2006) The duo low plasma brain natriuretic peptide and C-reactive protein indicates a complete remission of peripartum cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 108: 269-270.

-

Traore-Kissima Abdoulaye, Coulibaly Siaka, Haidara Ousmane, Cenac Arnaud*, Cissouma Assetou, Dembele Ahmadou, Soumaila Alama Traore and Dade Ben Sidi Haidara. Living Standards of 75 Hospitalized Black African Patients with Peripartum Cardiomyopathy. Study at Sikasso Hospital (Sikasso, Mali). On J Cardio Res & Rep. 6(5): 2022. OJCRR.MS.ID.000650.

-

Peripartum cardiomyopathy, African woman, Living standard, Sikasso, Heart failure, Heart failure, Cardiac disease, Climatic, Hormonal, Nutritional, Auto-immune, Infectious, Inflammatory factors

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.