Research Article

Research Article

The Role of Spirituality and 12 Step Groups in Addressing Treatment Fear and Worry Among Head and Neck Cancer Patients

Heather M Wallace, Department of Public Health, Grand Rapids, MI, USA.

Received Date: October 01, 2019; Published Date: October 16, 2019

Abstract

Diagnosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) presents a multifarious problem. Because of uncertainty regarding appropriate clinical treatment, as well as the high potential for disfigurement and functional loss resulting in diminished quality of life (QOL), satisfactory patient participation in quality decision-making is critical. Previous research has consistently revealed that older adults frequently defer decisionmaking to their physician and make decisions more quickly than younger adults. Research also suggests that lay health beliefs, past experiences and various strategies of emotional regulation, based on perceptions of the quantity and quality of remaining time till death, may influence the decisionmaking process. This qualitative study sought to explore the treatment decision making experience of adults with newly diagnosed head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, including laryngeal, esophageal, and oral cancers (N=41). In depth interviews were conducted at the time of diagnosis and after treatment completion. Interviews were transcribed and analyzed using the constant comparative method. Participants cited negative changes in appearance, resources, or relationships as well as pain, suffering, and the development or exacerbations of other health concerns as the most feared or worrisome aspect of treatment. Additionally, spirituality and spiritual practices as learned through 12 step group programs assisted participants in alleviating these fears and worries and provided a framework for navigating treatment decisions and the overall lived cancer experience. Principles of 12 step programs such as life review and reconciliation may provide valuable and useful benefits to patients across the illness experience.

Keywords:Cancer; Treatment decision making; Spirituality; 12 step group

Introduction

The collective term “head and neck cancer” refers to a constellation of malignant, clinically and biologically diverse tumors of the upper aero digestive tract, including the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx. Approximately 90 to 95% of all cancers in this anatomical region are squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) and share similar etiologic origin, epidemiology, treatment and prognosis 9 [1]. Most individuals presenting with HNSCC are men over the age of 65 with a history of tobacco and alcohol use [2]. The historical use of alcohol and tobacco, as well as abuse of other substances should raise concern and consideration for health care providers. Patients may enter the illness experience while using or abusing substances, may experience co-morbidities related to or exacerbated by substance use, or may deter or avoid health services in effort to avoid detection of substance use. Likewise, it should be noted that many patients with past or current addiction, may have experience with 12 step group programs that may impact treatment seeking and decision making.

As compared to other cancer populations, HNC patients are more frequently diagnosed at advanced stages, exhibit higher rates of smoking and alcohol use, have higher levels of mental illness, are at higher risk of developing secondary cancer sites, and are the most likely among all cancer populations to commit suicide within three years of diagnosis [3,4]. Additionally, HNC rates are rising in European and other Western countries, where rates were once among the lowest in the world [5]. Likewise, certain populations with previously low prevalence, such as older white men, have experienced significant increases in prevalence and mortality that are expected to continue to increase. Finally, HNC treatment is particularly traumatic, often producing physical, mental, and psychosocial problems for patients and their families. Despite improvements in diagnosis and local management, long term survival rates in head and neck cancer have not increased significantly over the past 40 years.

This qualitative study sought to explore and describe the cancer treatment experience specific to older head and neck cancer patients by identifying and describing factors that may be central to that experience. Of interest was the role of past or current addiction, including how cessation and drug rehabilitation programs, such as Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12 step programs may influence treatment decision making and or impact the overall cancer experience. Because Head and Neck cancer (HNC) often imparts overwhelming consequences to quality of life and physical functioning and because of increased risk of death and secondary tumor occurrence, improved understanding of the experience may lead to improvements in the detection and treatment of cancer while also improving patient satisfaction with care.

As rates of HNC continue to climb and mortality rates fail to decrease, researchers, public health professionals and practitioners must endeavor to identify both the causal mechanisms of HNC development and how patients respond to symptoms and make decisions throughout the illness experience. This study identifies fears and worries related to treatment that may prevent or deter optimal treatment and describes how principles of the 12- step model can be used as a complimentary approach to cancer treatment.

Materials and Methods

A qualitative approach was used to address the relatively unexplored process of decision-making within an older HNSCC population. The use of qualitative methods is well suited to the exploration of naturalistic decision-making and provides in depth identification and exploration of the most salient aspects of real-life decision making. Participants were recruited from the Department of Otolaryngology at a large medical teaching facility. Individuals over the age of 18, presenting to the clinic with a newly diagnosed HNSCC, and able to speak and understand English were invited to participate in the study. Eligible patients (N=41) were identified through the Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancer Nursing Coordinator and/or the treating head and neck oncologic surgeon. The study was approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board. Two semi-structured interview guides were developed to collect study data: (a) a pre-treatment interview guide, and (b) a post-treatment interview guide. Each guide was developed specifically for this study and was designed to facilitate an exploration of the HNC treatment experience. The average length for each interview was 74 minutes. The first interview was completed within 2 weeks of the patient receiving a new HNC diagnosis. As part of the first interview, participants were asked: 1) What is the most worrisome part of having your condition? And, 2) What things scare you or do you worry about regarding your condition? The second interview was completed after either treatment had ended or the patient had decided to stop undergoing treatment. Interviews were tape recorded and transcribed following each interview. Transcriptions were then coded and themed. A code book was kept that organized the codes into categories and subcategories and could be linked to concepts and emergent themes. A combination of explicative techniques as well as qualitative data analysis techniques suggested by Creswell [6] were used to identify themes related to treatment decision making among head and neck cancer patients.

Results

Fear and worry

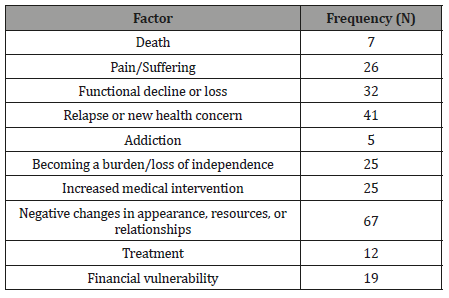

HNC treatment often brings significant physical and functional impairment. Previous studies have reported that patients fear changes that threaten aspects of self- identity such as changes to vocal tone or loss, feeding tubes, facial disfigurement, and or the ability to eat or talk [7]. At interview 1, participants reported the most worrisome aspects of their condition see Table 1. The frequencies and issues recorded in the table reflect a count of each type of worry identified by participants. For example, one participant said that “I might not get better. This might be the best I’ll ever be, right now.” He also worried about his appearance, stating “those stomas… I’ve seen others with one. That scares me a little I don’t want to look that way.” His responses are counted under functional decline or loss as well as under negative changes in appearance. Some issues were worrisome because they required more effort from the patients. For example, one patient worried that her condition would require her to attend more medical appointments, take more medication, and pay more attention to her health. Other things were worrisome because they represented loss of life, income, time or independence. Of the 41 participants, three indicated that they could not say or did not know what was most worrisome.

Table 1: Categories of Issues Reported as Most Worrisome (N = 41).

Participants also were asked what scared them. Interestingly, participants seemed to delineate fear from worry based on future health threats. In other words, many of the “worrisome” factors were linked to things that they perceived as threatened by the lifestyle consequences of their condition, rather than the condition itself. For example, radiation and surgery would no doubt influence work and/or pay which was worrisome, but there was perceived potential for long-term financial recovery. In addition, worrisome events often were events or issues that held uncertainty. In the above example, radiation and treatment may influence work and pay, but it was not a certainty. A person could survive treatment and return to a pre-diagnosis work status. On the other hand, future health threats like relapse, metastatic cancer, loss of function, and death can prevent social/instrumental recovery, which seemed to be the most feared attributes of having HNC. Fearful issues were frequently discussed as imminent or inevitable, rather than a potential possibility. One participant explained:

The thing that scares me the most is problems with being able to eat like I have in the past. We have dinner at our house every Sunday after church and anybody’s welcome. It’s usually the kids, you know. Food is good, it’s what keeps a family together, shows people you love them. When times are hard it’s the go to thing that keeps us connected. I really enjoy that time and I think that not knowing how all this will make me feel or keep, you know able to smell, taste, even eat, and be comfortable around food. I just want to be able to be a part of all of it having cancer is bad because of what it takes away from you if you survive.

In another interview, a participant reminisced about her worst fears regarding her health status in general. When asked about her tonsil cancer she told me that she was dealing with her fear like she had dealt with other problems.

I sit myself down and write a letter to the higher power. Somehow putting the words on paper makes it more real. I write down all the things that scare me about whatever I’m worried about, so I can figure out how to overcome it, and the number one is always the same: being a burden because I can’t take care on my own. It’s not about if I’m going to live or not, but how I’m going to do it.

One might imagine that hope associated with treatment would eradicate or at least allay significant worries and fears. When asked what participants hoped or wanted their doctor to do in order to help them, many (n = 17, 41.4%) simply replied that they wanted help “getting better,” to “provide a cure” or “manage pain.” An additional 13 participants (31.7%) said they didn’t know or weren’t sure what they wanted their doctor to do. Only nine participants (21.9%) provided detailed responses outlining specific actions, treatments, or outcomes.

Spirituality and 12 step programs

Spirituality grows out of hope and self-assessment, and grounds the sense of self internally, thus enabling patients to transcend their disease. For example, John, a gentleman in his early fifties, was devastated to learn of his diagnosis. He was very active and reported that he was very healthy and strong. During his treatment, he participated in a cancer support group where he met others who openly shared their fears and triumphs. It was at one of these meetings where he met a soldier who had survived the loss of his leg only to be diagnosed with testicular cancer 3 years later. John admired the soldier because he was so “brave confident and always humble,” characteristics that John came to believe he lacked in himself despite his physical strength and self-proclaimed success at hunting, fishing, and playing sports. The soldier offered to teach the support group members how to meditate and do guided imagery to help cope with their cancer. John agreed. During our second interview, John told me that he had first imagined himself as an eagle with a broken wing, unable to fly, belittled, vulnerable, and outraged. Eventually, after many months of imagery and meditation on the source of this initial image, John developed a new image of himself. It was a phoenix, the mythical bird that rises from the ashes to begin a new life. With this image of himself, John explained to me that he had found the freedom to love life as it comes, to love himself and to be respectful of the “blessings of life.”

Many participants in this study discussed aspects of spirituality that helped them to cope with their cancer and its treatment. Being mindful of one’s own strengths while also being humble was a particularly common spiritual component. Participants prayed, meditated, and “looked inside” of themselves, for answers and guidance and encouragement. Another way in which participants nourished their spirituality was by “doing for others.” People created opportunities to help others, such as taking time to be available to help a friend or family member; or volunteering time or resources to some cause. Of interest was the number of participants (n = 27) who intentionally sought ways to interact and assist others with similar problems. Unlike with breast and colon cancer, there are very few HNC support groups, and even fewer for specific cancers such as laryngeal. Twelve participants shared their stories with other substance users at cessation programs or 12-step programs. Eight reported that they had found and offered help in online blogs and chat rooms specific to their type of cancer. “I just wanted to share my story because when I got sick, I didn’t know anything or anyone who had had it, and when I found someone it made me feel like I wasn’t the only person with this,” remarked one participant. Others attended grief and cancer related workshops or groups, contributing their own “gifts” of knowledge or service.

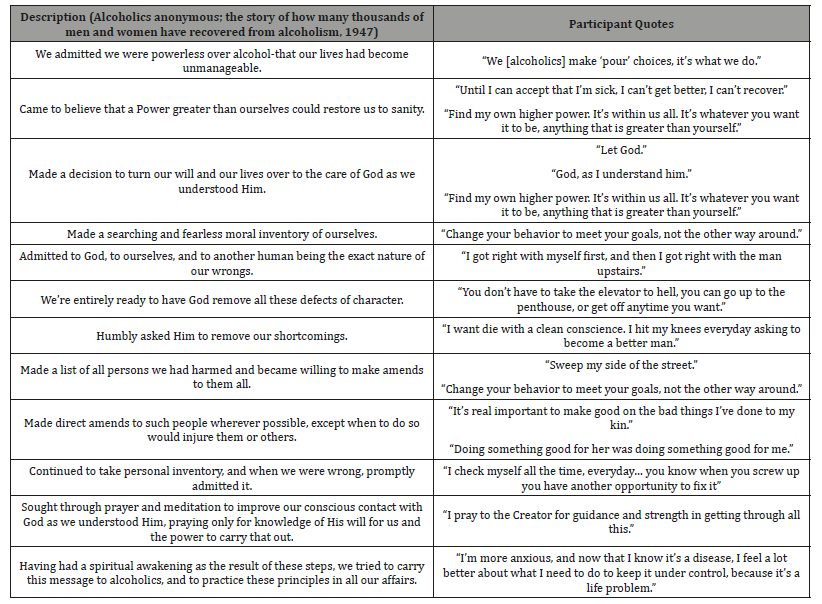

One of the most interesting patterns that emerged during data collection was the exposure to and or knowledge of 12- step programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). Thirty-one participants (76% of the study population) either directly identified AA experience or invoked 12-step language during the interviews. Twelve-step programs, commonly referred to as twelve-step groups (TSGs) are autonomous, self-help, community-based support groups for individuals who are addicted to substances (i.e., alcohol, cocaine, narcotics) or behaviors (i.e., gambling, sex, video games) [8]. TSGs are the most prolific resource for addiction recovery in the United States. In fact, it is estimated that there are at least 18 million AA members in the United States alone [9]. These programs generally rest on three pillars: unity, in the form of fellowship and tradition; service, to the organization/fellowship; and recovery [10]. Recovery is perhaps the most well-known aspect of 12-step programs and consists of “working” through the 12 steps (Table 2). Participation in a 12-step program is free, voluntary, anonymous, and independent of formal corporate, or organizational oversight [11]. While there is no formal recognition of a specific religious deity or body, TSGs are spiritual by design, encouraging participants to seek and rely upon a “higher power.” Table 2 identifies the 12 steps of Alcoholics Anonymous and participant quotes that relate to each.

Table 2: 12 Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous and Related Participant Quotes.

Discussion and Conclusion

TSGs have been consistently shown to be an efficacious intervention for cessation and sobriety. The mechanism by which success is achieved has been linked to enhanced self-efficacy [12], as well as social support and social networks [13]. A recent theory regarding AA and other TSGs is that the process of working the steps, as well as social support, facilitates the negotiation of grief and loss that accompany cessation and recovery from addiction [14].

In the present study, participants used TSG experience to navigate the treatment decision making experience broadly, and specifically in managing and overcoming their fears and worry related to cancer and cancer treatment decision making. The Twelve step model used by AA and other TSG’s relies heavily on the spiritual foundation of belief in a higher power and on undertaking personal reflection, personal responsibility, and personal acceptance and awareness, which may help patients to cope. Like alcoholism and other addiction, cancer creates profound uncertainty, limits choice, and may impede self-efficacy. The application of the 12 steps provided a useful and known framework for working with a problem (cancer and cancer related fears and worries), thereby offering participants a means to alleviate some of the personal fears that are not easily nor commonly acknowledged or managed by clinical medical practice and treatment.

It should be noted that many patients continue substance use after diagnosis and throughout treatment. In this study, several patients indicated that they were smokers or drinkers and that their addictions would be or had been a factor in their treatment experience. Services for cancer patients, particularly those with HNC, should include a formal means of identifying, addressing and supporting patients with co-occurring addictions to tobacco, alcohol, and/or other substances. TSG’s may serve as a valuable framework, and complimentary health approach to treatment, that provides meaningful support for head and neck cancer patients throughout their treatment and illness experience. Future research should be undertaken to explore how 12 step principles such as belief in a higher power, reconciliation, prayer and or meditation, and moral inventory may be translated and applied to cancer and other chronic, and complex health conditions.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study suggests a novel and innovative complimentary health approach that may be useful in alleviating some of the challenges, fears, and worries of head and neck cancer patients. This patient population experiences disparities in depression, treatment outcomes, and mortality. While clinical treatment options exist, few alternative and complimentary approaches have been identified and applied within this patient population. Future research should be undertaken to better understand the mechanisms by which TSG’s may influence treatment decision making and to explore how a broader array of patients may be served through TSG principles.

Acknowledgement

None

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Marur S, Forestier AA (2008) Head and neck cancer: Changing epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 83(4): 489-501.

- Siegel Rl, Miller KD, Jemal A (2019) Cancer Statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 69(1): 7-34.

- Haddad R, Annino D, Tishler RB (2008) Multidisciplinary Approach to Cancer Treatment: Focus on Head and Neck Cancer. Dent Clin of North Am 52(1): 1-17.

- Reid BC, Warren JL, Rozier G (2004) Comorbidity and early diagnosis of head and neck cancer in a Medicare population. Am Journal of Prev Med 27(5): 373-378.

- Franceschi S, Bidoli E, Herrero R, Munoz N (2000) Comparison of cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx worldwide: etiological clues. Oral Oncol 36(1): 106-115.

- Creswell JW, (2009) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches (2 ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Smith LK, Pope C, Botha JL (2005) Patients' help-seeking experiences and delay in cancer presentation: A qualitative synthesis. Lancet 366(9488): 825-831.

- Alcoholics anonymous; the story of how many thousands of men and women have recovered from alcoholism. (1947) New York: Works Pub.

- Gould M, (1999) Staying sober tips for working a twelve-steps program of recovery. from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=42760

- Ashenberg Strausner SL, Byrne H (2009) Alcoholics anonymous: Key research findings from 2002-2007. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 27(4): 349-367.

- Minnick AM, (1997) Twelve step programs: A contemporary American quest for meaning and spiritual renewal. Westport, Conn.: Praeger.

- Bogenschutz MP, Tonigan S, Miller WR (2006) Examining the effects of alcoholism typology and aa attendance on self-efficacy as a mechanism of change. J Stud Alcohol 67(4): 562-567.

- Laudat AB, Morgen K, White WL (2006) The role of social supports, spirituality, religiousness, life meaning and affiliation with 12-step fellowships in quality of life satisfaction among individuals in recovery from alcohol and drug problems. Alcohol Treat Q 24(1-2): 33-73.

- Streifel C, Servaty-Seib HL (2009) Recovering from alcohol and other drug dependency: Loss and spirituality in a 12-step context. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 27(2): 184-198.

-

Heather M Wallace. The Role of Spirituality and 12 Step Groups in Addressing Treatment Fear and Worry Among Head and Neck Cancer Patients. On J Complement & Alt Med. 2(3): 2019. OJCAM.MS.ID.000537.

-

Quality of life, Decision-making, Lay health beliefs, Principles of 12 step programs, Head and neck cancer, Squamous cell carcinomas, Tobacco and alcohol, Diagnosis

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.