Research Article

Research Article

Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease Among University Employees

Laura C Dobler1 and Kenneth R Ecker2*

1Department of Health and Human Performance, University of Wisconsin, River Falls, WI USA

2Department of Kinesiology, Pacific University, Forest Grove, OR USA

Kenneth R. Ecker, Ph.D., FACSM, Department of Kinesiology, Pacific University, Forest Grove, OR 97116.

Received Date: May 24, 2020; Published Date: June 17, 2020

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to compare cardiovascular disease risk among university administration and faculty employees (N = 47) with the general public as per National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data and American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommendations.

Methods: Health and wellness assessments were performed on public university employees comprised of body compositional analysis, blood lipid and glucose panels, dietary recalls, and blood pressure and then compared with the results of current NHANES data and ACSM recommendations using a one-way t-test and descriptive analysis.

Results: Descriptive results indicated that the sample’s means were above recommended values for male age, body fat percentage, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, and a diet too high in sodium and too low in calcium, fiber, and vitamin D. A one-way t-test indicated that the sample also had significantly higher diastolic blood pressure (p = .0008) and High Density Lipoprotein (p = .0005) and significantly lower blood glucose (p = .00001) than the national average.

Conclusion: These results indicate that the university employees were at significant risk for some cardiovascular disease risk factors and dietary choices, which indicates that they would benefit from health promotion programs that target those specific risk factors.

Keywords:Dyslipidemia, Body mass index, Cardiovascular disease

Short Communication

Cardiovascular disease is on the rise in the United States of America and around the world [1,2]. Approximately 1 in 4 deaths in the United States are caused by some form of cardiovascular disease [1,2]. Cardiovascular disease is extremely dangerous due to its often sudden onset and high mortality rate. One of the main reasons that cardiovascular disease is on the rise is because many of the risk factors for the disease are on the rise as well. Some risk factors are outside of one’s control, such as age, gender, and genetics. However, many risk factors for the disease can be modified through lifestyle changes and medical intervention. Modifiable risk factors include physical activity level, hypertension, prediabetes, dyslipidemia, diet, and obesity. It has been found that people of different socioeconomic classes, races, education levels, and geographic locations have different risks of cardiovascular disease [2]. Some research has been done to determine if there are differences in cardiovascular disease by occupation, however many of these studies are epidemiological and have only looked at overall mortality or determined how many people in certain occupations have been diagnosed with the disease. The majority of studies do not delve into rates of specific risk factors among occupations [1]. Additionally, those studies that do focus on occupations, focus on high risk or high stress occupations such as firefighters, police officers, laborers, etc. There are a lack of studies focusing on cardiovascular disease risk factors among jobs that are considered to be “white collar.”

White collar jobs are generally considered to be ones where the employees spend the majority of their day in an office or cubicle environment. While it may seem obvious that sedentary jobs such as these may cause an increase in cardiovascular disease risk due to their physically inactive nature, it is unclear if this is actually the case. Research has shown that an educational level often has an inverse relationship with cardiovascular disease risk (2). Many of the “white collar” jobs generally require a high education level. This leads to questions regarding if the benefits of having a higher education level outweigh the risks of having a sedentary job?

The purpose of this study was to examine cardiovascular disease risk factors among university employees, and to compare these results with standardized norms based on age and gender. In addition, this study will also be used to help guide programmatic offerings in health and wellness within the university. The following risk factors of cardiovascular disease were studied: age, gender, body composition, blood pressure, blood glucose, blood lipids, and diet.

Methods

Participants

In this study, there were 47 participants, 14 males and 33 females, ranging in age from 26 to 65 years. All participants were employed by the University of Wisconsin-River Falls in River Falls, Wisconsin, United States of America and volunteered for participation in the study to gain a better understanding of their personal health. Volunteers filled out a 3-day dietary recall and had resting blood pressure, body composition, fasting blood lipids, and fasting blood glucose measured. Fourteen volunteers failed to return their three-day dietary recall leaving 33 subjects available for dietary analysis.

Instrumentation and procedures

All participants were employed by the University of Wisconsin- River Falls in River Falls, Wisconsin, United States of America and volunteered for participation in the study to gain a better understanding of their personal health. Volunteers filled out a 3-day dietary recall and had resting blood pressure, body composition, fasting blood lipids, and fasting blood glucose measured. Fourteen volunteers failed to return their three-day dietary recall leaving 33 subjects available for dietary analysis.

Dietary recall

Subjects were asked to write down all the foods and beverages and amounts for three non-consecutive or consecutive days, depending on the subjects choosing. One day had to be a weekend day and two days had to be weekdays. Subjects were instructed to select days that were typical for them, this excludes days that they believe were atypical such as days where they consumed holiday meals or were sick and did not have their normal appetite. Subjects were given a standardized form for recording their dietary recall. Nutritionist Pro (Axxya Systems LLC, Redmond, Washington, United States) was used to analyze dietary recalls.

Body composition & BMI

Body composition and BMI were measured via the COSMED Bod Pod (COSMED USA, Concord, CA). The Bod Pod was calibrated between participants fully and participants were instructed to wear tight fitting clothing in order to ensure accuracy.

Resting blood pressure

Blood pressure was taken using a standard sphygmomanometer and stethoscope per the guidelines established by the American College of Sports Medicine in 2013 [3].

Blood lipid and glucose profile

Blood lipid and glucose profiles were measured using an Alere Cholestech LDX machine (Abbott Diagnostics, Livermore, CA). To maintain accuracy in the results, subjects were required to fast 12 hours prior to administration of the test but were instructed to consume ample water in order to maintain hydration.

Data analysis

The investigation was a descriptive study where mean and standard deviation values for male and female cardiovascular disease risk factors were assessed. These data points were then compared with national age and gender specific standardized norms and recommendations using a one-way t-test. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, United States) version 24.0 was used for statistical analysis. An alpha value of .05 was used to determine significance. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) [4] 2013- 2014 data was used for comparing the university employee physiologic data to that of the general public. The U.S Department of Health and Human Services and U.S Department of Agriculture (USDA) recommendations were used for dietary recommendations5.

Results

Physiologic data

Variables found to be, on average, within the ACSM Risk Factor range for cardiovascular disease [3] were female age, BMI, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure**, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol**, triglycerides, and blood glucose*.

Variables found to be, on average, higher than the ACSM Risk Factor range for cardiovascular disease [3] were male age, body fat percentage, and LDL cholesterol.

** = significantly higher * = significantly lower than the national average (p<.05).

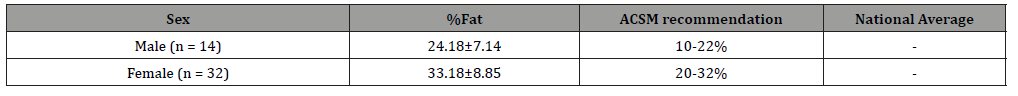

Body Composition

Table 1 shows the mean body fat percentage values for male and female participants. The participants were divided between male and female for these measurements because the ACSM recommended different values for male and female populations. This table also compares the sample’s means with the recommendations of the ACSM and those of the general population as described in NHANES 2013-2014. The sample of female UWRF employees had an average body fat percentage of 33.18 ± 8.85. This was greater than the ACSM recommendation of 20-32% fat (3). Out of the 32 female individuals, 15 (46.88%) were over 32% fat. Additionally, 1 of the individuals (3.125%) was under fat (<20% body fat). The sample of male UWRF employees had an average body fat percentage 24.18 ± 7.14. This was greater than the ACSM recommendation of 10- 22%9. Out of the 14 male subjects, 9 were over 22% fat (64.29%). Additionally, 1 individual (7.14%) was under fat (< 10% fat). Because there was no national data available in the NHANES data set for body fat, there is no statistically significant data available.

Table 1: Note: All values are described as Mean ± Standard Deviation. %Fat = Body Fat3. NHANES data unavailable for body fat percentage.

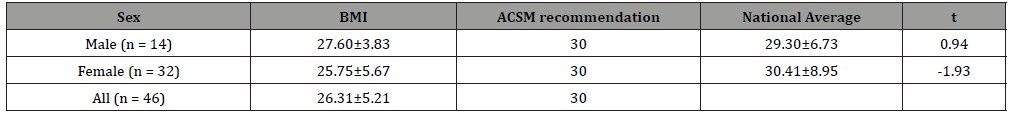

The sample of female UWRF employees had an average BMI of 25.75 ± 5.67 which did not put them in the risk factor range for cardiovascular disease. Only 4 out of the 32 (12.5%) subjects had a BMI of greater than 30 kg/m2. This was less than the national average (30.41 ± 8.95). However, there was no statistically significant difference between the sample and the national data (p = .054). The sample of male UWRF employees had an average BMI of 27.60 + 3.83 which did not put them at risk for cardiovascular disease. However, 3 out of the 14 (21.43%) subjects had a BMI of greater than 30 kg/m2. This was less than the national average 29.30 ± 6.73. Yet, there was no significant difference between the sample and the national data (p = .35).

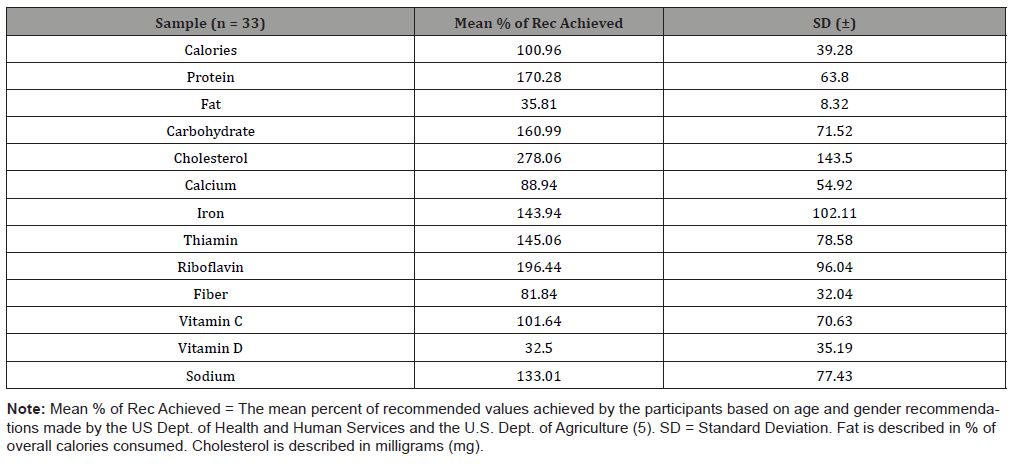

Three-day dietary recall

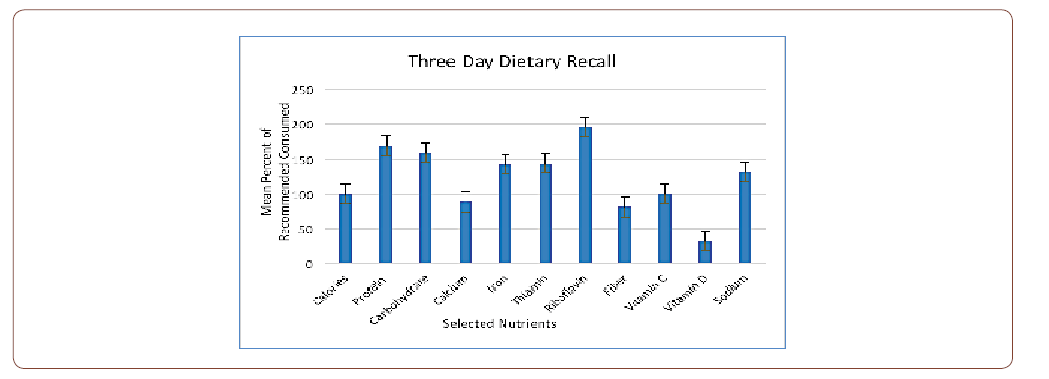

Table 3 shows the mean values of the subjects’ dietary recalls. Subjects recorded all food consumed for three days and the means were taken of these three days. Data is being compared to recommendations made by U.S Department of Health and Human Services and U.S Department of Agriculture (USDA) [5]. There were no data available from the NHANES data set and so there was no point of comparison to national averages. There appears to be excess consumption of many macro and micronutrients (protein, carbohydrates, sodium, cholesterol, iron, thiamin, riboflavin, and fat) and inadequate consumption of some micronutrient (calcium, fiber, and vitamin D) (Table 4).

Table 2: Note: All values are described as Mean ± Standard Deviation. BMI = Body Mass Index. All measures are described as body weight in kilograms/ height in m2. p <.05* (3).

Table 3:

Table 4:

Table 5:

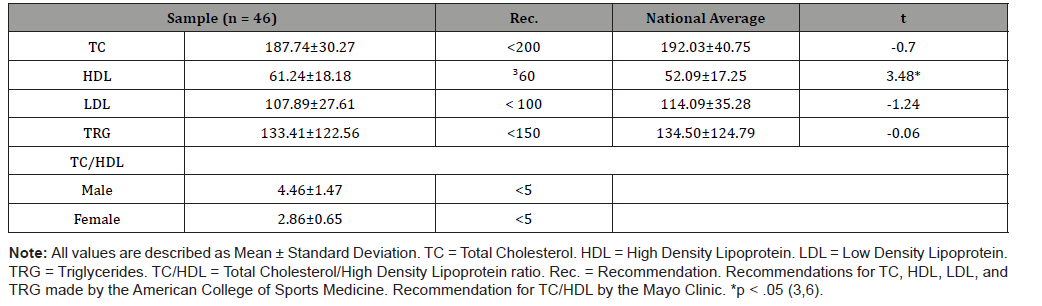

Blood lipids

Table 3 shows the mean values of Total Cholesterol (TC), High Density Lipoprotein (HDL), Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL), Triglycerides, and Total Cholesterol/High Density Lipoprotein ratio (TC/HDL). The table also compares these numbers with recommendations made by the ACSM and with those of the general population as described in NHANES 2013-2014.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine cardiovascular disease risk factors among university employees, and to compare these results with standardized norms based on age and gender. In addition, this study will also be used to help guide programmatic offerings in health and wellness within the university.

Body composition

While we found that the majority of our sample was within normal limits for BMI, they were above recommended limits for body fat percentage. This may be due to the fact that some of the participants may have had a normal body weight for their height, but a high percentage of fat. This is likely because BMI is a measure that does not differentiate between muscle mass and fat mass. It was found to be extremely helpful to measure both BMI and body fat in this study in order to learn of the obesity status of individuals. It may be possible that other studies may have had similar results if they would have measured body fat as well. It is likely that many of our participants who were found to have normal BMI, but above recommended percent fat have normal body weights, but less muscle mass than recommended. This information is highly helpful because it can help to determine that future health promotions at the university level should incorporate resistance training exercises (weightlifting, resistance training, plyometrics, etc.) into their program.

Due to the sedentary nature of white-collar jobs [7], these results were not unexpected. Body fat percentage that is above recommended values can be caused by a variety of factors including, but not limited to, sedentary lifestyle, poor diet (above recommended consuming of calories and other nutrients or below recommended amounts of some nutrients), genetics, and certain medications. In the future it would be extremely helpful to additionally study physical activity trends in the sample to help determine the causes of these rates of obesity. Some of the groups (when divided between age and gender) exhibited above normal calorie consumption, which may have contributed to this trend.

Body mass index

Gu et al. [8] studied obesity rates in different types of occupations using BMI. They found that 16.8% of male employees measured who were employed as post-secondary educators were classified as obese [4,9]. This is 5% less than what we saw in our sample; however, this is most likely due to small sample size. For females, 16.1 % were classified as obese. This is higher than what we found by 4%. This is also likely due to our small sample size limitation. In Gu et al. [8], there were 465 males and 470 females. In our study, there were 32 females and 14 males. Alkhatib [9] found that his 34 subjects had a mean BMI of 25.1 + 4.3 kg/m2 5. Our sample had a mean BMI of 26.31 + 5.21, slightly higher than that of Alkhatib [9]. These numbers are close, however, and both are within the ACSM’s recommendation of less than or equal to 30 kg/ m2 [3].

Body fat

Alkhatib [9] found that their 15 male subjects had a mean body fat percentage of 26.2 + 5.0 and their 19 females had a mean of 32.4 + 6.8 9. Our male subjects had body fat percentages of 24.18 + 7.14, 2% lower than Alkhatib’s subjects. Conversely, our female subjects had a mean value of 33.18 + 8.85, 1% higher than Alkhatib’s subjects. Although these values were 1 and 2 percent different between the two studies, they were both above the ACSM’s recommended values.

It is concerning that our sample was found to be over the recommended percent body fat range because, as previously stated in the literature review, having a high percent fat can be a contributing factor for many diseases, not just cardiovascular disease [10]. Overall, about 52% of our sample was considered to be overweight or obese by body fat percentage. While this is less than the believed rate of obesity and the overweight condition in the US, two thirds of those living in the US are considered overweight or obese [11]. It is still a cause for concern because this put half of our sample to be at an increased risk for cardiovascular disease. This is a very large number. It is a possibility that many of these people take their health for granted, and don’t know the exact dangers of being overweight or obese. Therefore, educational sessions may help those affected to have a greater desire to lose weight.

Three-day dietary recall

In the dietary recall portion of the study, only 33 out of the 47 (70.2%) total participants returned their diet information, this may have been due to many factors, including, but not limited to time availability, memory issues, desire to complete, motivation level, and embarrassment. However, we were not able to survey individuals about their reasons for not completing, so plausible reasons are only speculative. In the future, it may be helpful to incentivize the dietary recall portion of the study by offering follow up appointments to go over the results of the subjects’ recalls and suggest possible dietary modifications. When dividing the subjects into groups by age and gender necessitated by the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services and Agriculture, the groups became very small (between 3 and 11 subjects per group) to the point where there could certainly be error.

Macronutrients

While the mean amount of calories consumed for all subject was 100.96 ± 39.28 of the recommended amount for age and gender, two groups were on average above the recommended amount and two groups were on average below the recommended amount. Males from ages 31 to 50 consumed about 200 more calories on average than recommended, and females over age 51 consumed about 150 calories more calories on average than their recommended amount. Generally consuming excess calories is due to overeating in the diet. Females ages 19 – 30 consumed about 550 calories per day less than recommended on average. This was not unexpected because these are common ages where women feel pressure to have a slim figure, and these young women may have been intentionally eating less in order to keep their weight down. In addition, men over the age of 51 under-consumed around 250 calories for their dietary needs on average. A cause for this may be that some men may not like to cook or prepare meals where this may lead to a deficit in caloric intake. Under consuming calories can be caused by a variety of factors such as misinformation about the body’s caloric needs, caloric content of foods and possibly a desire to lose weight.

Micronutrients

In the dietary recall portion of this study, there were many variables in which the subjects obtained adequate amounts of the nutrients they required. Overall, subjects consumed adequate amounts of iron, thiamin, riboflavin, and vitamin C. There major exceptions for some nutrients. Women between the ages of 19 and 30 years require 18 mg of iron per day and only consumed 12.33 ± 1.15 mg on average. Women of this age are recommended to consume extra iron because they are of childbearing age. The amount may be difficult for them to consume in adequate amounts due to many factors including dietary preferences, lack of knowledge of iron containing foods, and lack of knowledge of the need for iron in the diet. Decreased dietary consumption can lead to symptoms such as lethargy. Men between the ages of 31 and 50 were deficient in consuming adequate amounts of vitamin C. They required 90 mg per day and only consumed a mean amount of 65.50 ± 62.76 mg. This may also have been caused by a lack of knowledge of the need for iron in the diet, no desire to consume vitamin C containing foods, or a possible error due to the small sample size (n = 4).

Other micronutrients where age and gender groups did not consume adequate amounts were calcium, fiber, and vitamin D. The reasons for not consuming these in adequate amounts are speculative, as we did not survey individuals on their food choices or follow up with individuals about food knowledge and preferences.

Females between the ages of 19 and 30 years and those more than 51 years old also did not consume adequate amounts of calcium. Women between the ages of 19 and 30 consumed, on average about 200 mg less than the recommended amount of 1000 mg, while women more than 51 years of age consumed on average almost 400 mg less than their recommended amount of 1200mg. This is noteworthy because women are at greater risk for developing osteoporosis than men, and thus need more calcium in their daily diet [12]. All age and gender groups’ mean values, except for women more than 51 years of age, were deficient in their fibre intake. This may be due to dietary choice such as a lack of choosing whole grain foods (the USDA recommends that Americans consume half of their grains in as whole grains [5]. This may also be due to lack of knowledge of what foods are good sources of fibre.

There were some micronutrients where age and gender played a role in consuming very high amounts of sodium and cholesterol. All groups consumed excess sodium. However, males between the ages of 31 and 50 consumed sodium the most. They averaged 4064.25 ± 433.50 mg on average. The recommended amount for all groups was less than 2300 mg per day. Between all groups, the average sodium consumption was 133.01% of recommended or about 3059.23 grams per day. This may be due to consuming overly processed foods or possibly adding more salt to their food choices. Research has found that high sodium diets are linked to an increased risk for cardiovascular disease [13].

The U.S. Department of Agriculture and Department of Health and Human Services recommend that dietary cholesterol be monitored for a healthy diet [5]. Men between the ages of 31 and 50 years consumed the most dietary cholesterol (354.50 + 177.51 mg), followed by women over the age of 51 (247.33 +77.49 mg), females between the ages of 31 and 50 (271.42 + 146.38 mg), males over the age of 51 (247.33 + 77.49 mg), and females between the ages of 19 and 30 (243.00 + 34.70 mg). The general recommendation for dietary cholesterol is less than 300 mg a day [5]. According to this standard, all groups studied in this investigation, except men between the ages of 31 and 50 years, would fall into the acceptable range. Dietary cholesterol comes from animal products, and thus the consumption of dietary cholesterol in excess may be due to excess consumption of animal products in these groups.

Blood lipids

Other studies that focused on faculty and staff of universities did not include data on all cholesterol consumption. The studies that did provide information on cholesterol mainly focused on total cholesterol [9]. Because of this, it is difficult to draw conclusions based on comparison points found in other studies. In this investigation no subjects reported taking any prescribed lipid lowering medications.

The UWRF sample had a mean total cholesterol of 187.74 ± 30.27 mg/dl. This was in the ACSM recommended value of <200 [3]. This was less than the national average of 192.03 ± 40.75 mg/ dl. However, it was not significantly less (p = 0.48). One study did provide information on total cholesterol but did not provide High Density Lipoprotein (HDL), Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL), or Triglyceride levels [9]. Alkhatib [9] found that his subjects had a mean total cholesterol level of 189.48 ± 27.07 mg/dl. These numbers were extremely close to what we found in our subjects. These healthy cholesterol levels are extremely encouraging to see because dyslipidemia is often referred to as a silent killer due to its relationship to the possible development of coronary artery disease [9]. Healthy mean total cholesterol values can be determined by a variety of factors including a healthy diet, regular physical exercise, and genetic factors.

The UWRF sample had a mean HDL value of 61.24 ± 18.18 mg/dl. This was significantly higher than the national average of 52.09 ± 17.25 mg/dl (p = 0.0005). It was also higher than the ACSM recommendation value of 60 mg/dl [3]. Our sample may have had a higher mean HDL level due to the higher number of women in the sample than men. According to the American Heart Association, women frequently have higher HDL levels than their male counterparts, due to their higher levels of estrogen (the female sex hormone that can raise HDL [14]). This was very encouraging because HDL cholesterol is linked to a lower rate of cardiovascular disease when the level is > 60 mg/dl [3]. Maintaining a high HDL level is extremely important factor for cardiovascular health.

The UWRF sample had a mean LDL value of 107 ± 27.61mg/ dl. This is lower than the ACSM recommended value of <130 mg/dl [3], and it is not significantly different than the national average of 114.09 mg/dl (p = 0.21). The UWRF sample had a mean triglyceride level of 133.41 ± 122.56 mg/dl. This was less than the ACSM risk factor value of <150 mg/dl [3]. The sample’s population was very comparable with the national average (134.50 mg/dl ± 124.79 mg/dl). The groups were not significantly different (p = 0.95). The UWRF male sample had a mean of 4.46 ± 1.47 for their Total Cholesterol/High Density Lipoprotein (TC/HDL) ratio. The female UWRF sample had a mean of 2.86 ± 0.65 for their TC/HDL ratio. These mean ratio values are within the Mayo Clinic’s recommended value of less than five [6]. There was no national data available for this information, so there is no statistically significant analysis available for this data.

Conclusion

While some of the variables in this study appeared to be significantly under control within the sample’s current lifestyles, some fell short. These short comings may be due to lifestyle or genetic factors. In future investigations, it would be informative to study lifestyle choices via survey to determine the reason behind these results.

In addition, it would be of interest to survey for past medical history, tobacco use, and physical activity level to more fully determine total risk for cardiovascular disease among this population.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- (2015) Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2013 on CDC WONDER Online Database, Released 2015. Data Are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2013, as Compiled from Data Provided by the 57 Vital Statistics Jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. CDC, NCHS, Web.

- (2015) Heart Disease Facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Web.

- Pescatello, Linda S (2013) ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. In: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health, (10th edn), Philadelphia, USA.

- (2016) The National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "NHANES 2013–2014." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Web.

- (2015) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 8th

- Chandler, Stephanie (2016) Understanding the Cholesterol Ratio. The Nest.

- Schroer S, J Haupt, C Pieper (2014) Evidence-based Lifestyle Interventions in the Workplace--an Overview." Occup Med 64(1): 8-12.

- Gu Ja K, Luenda E Charles, Ki Moon Bang, Claudia C Ma, Michael E Andrew, et al. (2014) Prevalence of Obesity by Occupation Among US Workers. J Occup Environ Med 56(5): 516-528.

- Alkhatib Ahmad (2013) Sedentary Risk Factors across Genders and Job Roles within a University Campus Workplace: Preliminary Study. J Occup Health 55(3): 218-224.

- Eckel RH (1997) Obesity and Heart Disease: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals from the Nutrition Committee, American Heart Association. Circulation 96(9): 3248-3250.

- Flegal, Katherine M, Margaret D Carroll, Brian K Kit, Cynthia L Ogden (2012) Prevalence of Obesity and Trends in the Distribution of Body Mass Index Among US Adults, 1999-2010. JAMA 307(5): 491-497.

- (2016) What Women Need to Know - National Osteoporosis Foundation. National Osteoporosis Foundation.

- Strazzullo P, L D'elia, NB Kandala, FP Cappuccio (2009) Salt Intake, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Disease: Meta-analysis of Prospective Studies. BMJ 339: b4567.

- (2016) American Heart Association. Women and Cholesterol.

-

Laura C Doble, Kenneth R Ecker. Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease Among University Employees. On J Complement & Alt Med. 4(3): 2020. OJCAM.MS.ID.000589.

-

Dyslipidemia, Body mass index, Cardiovascular disease, Physical activity level, Hypertension, Prediabetes, Dyslipidemia, Diet, Obesity

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.