Research Article

Research Article

Medical Cannabis: Attitudes and Practices of Providers and Patients in Vermont

Kitty Victoria*, Jessica Lyon, Kim Dittus, Maura Barry and Shelly Naud

University of Vermont Medical Center, USA

Kitty Victoria, University of Vermont Medical Center, 111 Colchester Ave Burlington, Vermont 05401, USA.

Received Date: March 20, 2020; Published Date: April 20, 2020

Introduction

With greater decriminalization of cannabis, attitudes of the general public, patients and healthcare providers are changing. Along with attitudes changing, more research is emerging demonstrating the potential therapeutic value of cannabis. The potential of cannabis as an adjunctive medication for chronic pain or potentially as an opioid replacement is now of special interest in light of the opioid epidemic. A Pew Research Center study reported that the majority (62%) of Americans now support legalization of marijuana, this represents a more than doubling of the percentage of Americans supporting cannabis legalization over the last twenty years [1].

Vermont law

In 2004 Vermont became the 9th state to approve medical cannabis (MC) for persons with severe illness. Subsequently, in 2011, Vermont enacted legislation allowing dispensaries to provide MC to patients. Qualification for MC use varies by state, but generally requires an application with verification of a qualifying condition by a certified medical professional. In Vermont, a healthcare professional must verify that the patient has a qualifying condition and has a “bone fide healthcare professional-patient relationship.” Bone fide relationship is defined as greater than three months (except in the case of a terminal disease). Qualifying conditions in Vermont include cancer, multiple sclerosis, HIV, AIDS, Crohn’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, glaucoma, PTSD (which requires a Mental Health Care Provider Form), and chronic medical conditions that are debilitating, and produce one or more of the following intractable symptoms: cachexia or wasting syndrome, chronic pain, severe nausea, or seizures [2]. Recent years have seen an exponential increase in the number of patients belonging to the medical marijuana registry. On July 1, 2018, recreational marijuana became legal in Vermont. Adults 21 and older can possess up to one ounce of cannabis or two mature plants. Vermont has yet to establish any regulatory framework for retail sales.

The rise of cannabidiol (CBD)

In September 2018, we saw the first rescheduling of whole plant derived CBD, Epidiolex® by the FDA for refractory pediatric seizure disorder, classified as schedule V4. The reclassification of CBD to Schedule V only applies to Epidiolex®; CBD from other sources remains schedule I [4]. This is an unusual situation as schedule I is defined as “substances, or chemicals defined by the federal government as drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” The disconnect exists in that the CBD and Epidiolex® share similar chemical composition and biological activity, however Epidiolex® is labeled as schedule V while the CBD remains schedule I. Despite confusing legal implications, demand for CBD from patients for a variety of indications including insomnia, anxiety, pain, neuropathy, headaches, spasm and seizures continues to rise.

Lack of Research and Education: Lack of research prevents gathering evidence, therefore evidence based medical education cannot progress. This leads to reliance on resources that have little reliability which hampers the discussion between health professionals and patients in regard to treatment recommendations. An article in the Clinical Journal of Oncology reported that while 80% of oncologists have discussed MC with their patients, only 29.4% of surveyed physicians feel knowledgeable enough to recommend medical marijuana to patients, and among those that have recommended medicinal cannabis 56.4% did not feel informed enough to do so comfortably [5]. Studies have shown that greater than 80% of physicians believe education on MC should be incorporated into medical education and that further research is needed [6-8]. Healthcare providers remain somewhat handicapped by the paucity of clinical research in MC with which to guide their patients. Federal Schedule 1 status poses a barrier to research for both MC and CBD as it requires a lengthy process of DEA licensing and site visits.

We report on the results of an online survey of physicians and nurse practitioners/advanced practitioners (NP/AP) as well as a paper survey of oncology patients in Vermont conducted from April to June of 2018. Information regarding attitudes, formal education, perceived uses, benefits and disadvantages of MC was collected.

Methods

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Vermont (UVM) Institutional Review Board.

Instrument

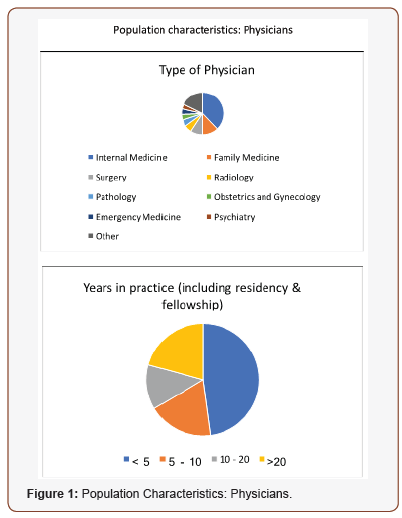

For the physicians and AP/RN survey we utilized a 15-item questionnaire which was based on questions used in other similar studies, expert opinion from a panel of MC educators, oncologists at UVM, and patient advocates. Two versions of the survey were designed with slight modifications for physicians and advanced practitioners. The first section focused on characteristics of the responders and the second section asked general questions about MC and CBD (Figure 1).

We designed an 11-item patient survey asking questions pertaining to use of MC, types of MC used, indications, frequency of use, whether they are enrolled in the registry, source of information, and if they have discussed MC with their doctor. The items were based on questions asked in similar studies and feedback from oncologists, patient advocates, and nursing staff (Figure 2).

Study Participants and Data collection

Participants for the email survey were residents, fellows, physicians and AP/RN in Vermont. For the paper survey, participants were oncology patients at the UVM outpatient clinic. Surveys were left in an optional patient survey area next to registration.

Recruitment

Recruitment for the email survey was done via university email lists and the Vermont Medical Society membership email list. We also had a link and small description published in a university online journal.

Recruitment for the paper survey was done during registration of patients at the university oncology clinic.

Analysis

The chi-square test was used for most group comparisons. Fivepoint scales were collapsed into three for the analysis. Several of the health conditions had very low endorsement rates, therefore we collapsed endorsements across all products (medical cannabis, THC, CBD, THC/CBD) and used Fisher’s exact test. The software used for the analyses was SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Physicians and APs:

141 physicians and 60 advanced practitioners filled out the email survey. As in Figure 1A, the population of physicians had more females than males, median time in practice was 5 years, the majority was from internal medicine and family medicine. The AP and nurse group was almost half NP and half AP from a wide range of specialties. Median time in practice was 10 years (Figure 3).

From the physician group, 90% had been asked about marijuana and 96% had been asked about CBD from a patient or family member. In the AP/NP group, 96% had been asked about both marijuana and CBD. For the question “do you believe that MC has important health benefits”, we utilized a Likert scale with 5 choices (strongly disagree to strongly agree). Five percent of the physicians fell into the disagree, over 50% in the strongly agree and agree, and the remainder were neutral. In the AP/PA group, 75% fell in the strongly agree or agree categories, none chose disagree (Figure 4).

We took the physician group and sectioned it into “have” and “have not” had education in MC. Attitudes towards MC were highly correlated with health professionals having had formal education (Figure 5). 75% of physicians and 68% of AP/RN had no formal education in MC. Physicians who had formal education were much more likely (p= 0.0073) to think that MC had health benefits than those without (87% vs 55%). Regarding the follow up question, which asked participants to identify which products they felt had important health benefits, those with education chose CBD and high CBD/low THC products as having the most health benefits more frequently than those without teaching (p < 0.001). Residents and fellows were less likely to recommend MC than faculty physicians (57% vs 37%, p = 0.0004).

Physicians were asked for which indications they would recommended a cannabis product. Sixty-nine percent of physicians with education in MC selected chronic pain vs 23% of those without education. Additionally, 48% with education chose nausea, appetite and musculoskeletal pain vs 19%, 24% and 15% respectively. MC was chosen by both groups as the top recommended product rather than THC, CBD, or THC-CBD, but overall, 58% chose “I do not recommend any specific product.”

Lack of education stood out as the greatest barrier to recommending MC followed by were legal implications, safety concerns, and side effects. Eighty-five percent of physicians surveyed and 87% of APs surveyed agreed that education on MC should be formally incorporated into medical education (Figure 6).

Patients

Fifty patients filled out the paper surveys. Patients were evenly spread across many cancer types, with the majority having breast, colorectal, and lung cancers. Out of the total, 56% were actively using MC, but only 34% were enrolled in the registry. Forty-six percent of patient respondents reported daily use. Fifty six percent had discussed MC with a physician while 76% answered yes to desiring more information about MC from a medical professional. However, only 24% had received their information about MC from a physician, with 58% citing friends/family as their information source.

Discussion

The results of our study show that of the Vermont medical providers surveyed (about 20% of Vermont physicians), many are in favor of more formalized education in MC. Additionally, this article highlights that having had formal education in MC does affect recommending patterns of medical providers. The physicians with education were more likely to answer that MC has health benefits and more likely to recommend MC overall for a number of indications. As in prior studies, we show that lack of education is the greatest barrier to recommending MC [5]. More physicians with education on MC chose pain as their primary indication for MC, consistent with previous survey results [9-11] (Figure 7).

This is the first study that we know of to ask specifically about different formulations of cannabis products (CBD, MC, THC, high THC/low CBD, low CBD/high THC). Previous studies have demonstrated knowledge gaps in medical providers regarding the various products at dispensaries and their respective uses [11]. This is exemplified in our results showing that 58% do not recommend any specific product. Additionally, those with education felt that CBD and high CBD/low THC had the greatest health benefit, even though the efficacy of CBD is currently supported by the least amount of clinical data as compared to other forms of MC [12].

The majority of both the AP/RN and physician groups had no formal education in MC. A 2017 survey of US medical schools found that 85% of medical students had not had any education in MC and that only 9% of medical schools were reporting some sort of education in their curriculum [7]. Studies published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine and the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine both report that greater than 80% of physicians believe education on marijuana should be incorporated into medical school and residency education and an almost unanimous desire for further research on cannabis exists among surveyed medical students9-11. This emphasizes the ongoing difficulty physicians experience in being improperly prepared to counsel their patients on the appropriate uses of MC. These issues become especially important when physicians are not aware of potential drug interactions in patients on multiple pharmaceutical medications, particularly in those patients receiving therapies with low therapeutic index or high potential for toxicity.

In our small survey of oncology patients, we see that over half are actively utilizing MC. However, a much smaller proportion are discussing this with their physicians despite a desire to do so. Twenty-two percent of the patients actively using MC are not enrolled in the registry, and therefore they are not receiving their MC from a dispensary. This will likely be a more common occurrence in states that legalize recreational cannabis as pricing, physician biases, paperwork involved, and time to become enrolled often serve as obstacles for patient registry initiation. A similar result was seen in a Colorado study of cancer patients. Almost all surveyed patients expressed a desire to learn more about cannabis, with 74% of patients reporting their preferred educational resource as their physician. However, only 15% received their information on medical marijuana from their healthcare team. The most common resources reported among patients were family/friends (as in our study), web and print media, and other patients [12].

This study and numerous others show that the overwhelming majority of healthcare providers are being asked about MC by their patients, and this study showed that 96% of medical providers are also being asked about CBD. Given that whole plant CBD has recently been FDA approved in the form of Epidiolex® and that the FDA has declared that all cannabinoids are in the category of “drug”, there is a need for greater research and education regarding marijuana and its constituents. We will undoubtedly see an exponential increase in the use of cannabis, number of formulations, variety of delivery systems, and breadth of indications. We must begin preparing medical providers to help guide patients with correct evidenced based knowledge. As previous studies indicate, the medical community and the American public supports the down scheduling of cannabis. We can only hope that this will allow for more uniformity across state lines, better integration into medical education, and easier access for researchers (Figure 8).

Limitations of our study include the fact that only fully licensed physicians are able to sign MC registration forms, whereas residents, fellows, and AP/RN are not permitted to do so. As patients are often aware of this requirement, it may alter their patient experience. Additionally, in Vermont medical providers do not formally prescribe or recommend any specific MC product; they merely qualify the patient for clearance to join the registry. When signing the marijuana registration form, physicians are simply verifying that patients have a qualifying condition and not supporting the usage of MC for that condition. This is a common practice in many states as physicians fear the implications of recommending a federally illegal drug. As a result, patients are often advised on dosing, formulation, and indication by the dispensary staff and not a medical professional. There could be a selection bias in the medical providers that decided to fill the survey out in that they may be intrinsically more interested in the topic. We had a greater proportion of women and internal medicine/family medicine healthcare providers, therefore these results cannot be generalized to all Vermont medical practitioners.

Even with the limitations, our study provides valuable information that may assist in decisions related to medical education in MC, need for greater access to research, and policy.

Acknowledgement

We received no funding for this studys

Author Disclosure Statement

Author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Geiger A, Hartig H (2019) 62% of Americans favor legalizing marijuana. Pew Research.

- Registry D (2019) Medical and Mental Health Professionals.

- Service CR (2018) Hemp Farming Act of 2018, In 115th

- Drug Enforcement Administration (2018) Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Certain FDA-Approved Drugs Containing Cannabidiol; Corresponding Change to Permit Requirements. In Federal Register: The Daily Journal of the United States Government National Archives.

- Braun IM, Wright A, Peteet J, Meyer FL, Yuppa DP, et al. (2018) Medical Oncologists' Beliefs, Practices, and Knowledge Regarding Marijuana Used Therapeutically: A Nationally Representative Survey Study. J Clin Oncol 36(19): 1957-1962.

- Kondrad E, Reid A (2013) Colorado family physicians' attitudes toward medical marijuana. J Am Board Fam Med 26(1): 52-60.

- Evanoff AB, Quan T, Dufault C, Awad M, Bierut LJ (2017) Physicians-in-training are not prepared to prescribe medical marijuana. Drug Alcohol Depend 180: 151-155.

- Chan MH, Knoepke CE, Cole ML, McKinnon J, Matlock DD (2017) Colorado Medical Students' Attitudes and Beliefs About Marijuana. J Gen Intern Med 32(4): 458-463.

- Carlini BH, Garrett SB, Carter GT (2017) Medicinal Cannabis: A Survey Among Health Care Providers in Washington State. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 34(1): 85-91.

- Abrams DI (2016) Integrating cannabis into clinical cancer care. Curr Oncol 23(2): S8-S14.

- Uritsky TJ, McPherson ML, Pradel F (2011) Assessment of hospice health professionals' knowledge, views, and experience with medical marijuana. J Palliat Med 14(12): 1291-1295.

- Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, Di Nisio M, Duffy S, et al. (2015) Cannabinoids for Medical Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 313(24): 2456-2473.