Review Article

Review Article

Love-Object Set Against Sex-Object: Appraising Two Associated Objects

Saeed Shoja Shafti*

Department of Psychiatry, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Razi Psychiatric Hospital, Iran

Saeed Shoja Shafti, Professor of Psychiatry, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Razi Psychiatric Hospital, Tehran, Iran.

Received Date: April 27, 2020; Published Date: June 16, 2020

Summery

During counselling or psychotherapeutic sessions, there are a lot of persons that introduce their partner as their absolute sweetheart and companion, while criticize them, as well, regarding their incompetence with respect to gratification or provision of anticipated sexual or romantic desires. Many of them may describe their partner as asexual, hypoactive or dishonest, while their own displeasure or jealousness may have root in a mismatch between sensual yearnings and spiritual longings.

Now a question may arise that whether sex-object is equal to love-object, or they are unalike things with different intentions and tasks. Developmentally, while the sex-object may or may not be at the same time a love-object, the love-object can not be anything except than an ultimate item derived from sex-drive, though in a more sublimated shape. If we see sex-object and love-object as unalike items with diverse goal lines, such a distinction may assist patients toward achievement of better insight with respect to their judgments, object-related conflicts and ambivalences, which possibly will guide their expectations towards more realistic objectives and less bewilderment as regards their constant displeasures.

Keywords:Object; Sex-object; Love-object; Sexuality

Introduction

One of the major interesting questions in the realm of emotive behavior and psychodynamic analyses involves assessment of object-related cathexis and the specific atten\tion that is paid to object’s sensual or loving aspects [1,2]. During counselling or psychotherapeutic sessions, there are a lot of patients that introduce their partner as their absolute sweetheart and companion, while criticize them, as well, regarding their incompetence with respect to gratification or provision of anticipated sexual or romantic desires. Many of them may describe their partner as asexual, hypoactive or dishonest, while their own displeasure or jealousness may have root in a mismatch between sensual yearnings and spiritual longings.

Now a question may arise that whether sex-object is equal to love-object, or they are unalike things with different intentions and tasks, which have been nominated by way of evolution thru history. If so, then how therapist or counselor can help their clients to gain insight regarding their mate and correct or modify their expectations according to their genuine desires and partner’s competencies. Essentially, is such a separation possible? Is it sensible to reduce, conceptually, companion’s position from an adoring lover to merely an actor of sexual role? For enlightenment of query, some review of associated concepts seems valuable.

Background

In general, the basic assumption of contemporary object relations theories is that all internalizations of relationships with significant others, from the beginning of life on, have different characteristics under the conditions of peak affect interactions and low affect interactions [3]. Under conditions of low affect activation, reality-oriented, perception-controlled cognitive learning takes place, influenced by temperamental dispositions (i.e., the affective, cognitive, and motor reactivity of the infant), leading to differentiated, gradually evolving definitions of self and others [3].

These definitions start out from the perception of bodily functions, the position of the self in space and time, and the permanent characteristics of others. As these perceptions are integrated and become more complex, interactions with others are cognitively registered and evaluated, and working models of them are established. Inborn capacities to differentiate self from non-self, and the capacity for cross-modal transfer of sensorial experience, play an important part in the construction of the model of self and the surrounding world [4]. The capacity for mutually satisfying relationships has been traditionally attributed to the ego, although self-other relationships are more properly a function of the whole person, the self, of which the ego is a functional component [5].

Significance of object relationships and their disturbance - for normal psychological development and a variety of psychopathological states - was fully appreciated relatively late in the development of classical psychoanalysis [6]. The evolution in the child’s capacity for relationships with others, progressing from initial relations with maternal and other caretaking figures to social relationships within the family and then to relationships within the larger community, is related to this capacity [6]. Development of object relationships may be disturbed by retarded development, regression, or conceivably by inherent genetic defects or limitations in the capacity to develop object relationships, or impairments and deficiencies in early caretaking relationships [7].

The earliest manifestations of infantile sexuality arose in relation to bodily functions that had been regarded as basically nonsexual, such as ‘feeding and development of bowel and bladder control’. But Freud saw that these functions involved degrees of sensual pleasure which he interpreted as forms of psychosexual stimulation, and divided them into a succession of developmental phases, each of which was thought to build on the completion of the preceding phases namely the oral, anal, and phallic phases. Urethral, latency, and genital phases were added, later, to complete the picture [8].

For each of the stages of psychosexual development, Freud delineated specific erotogenic zones that gave rise to erotic gratification. Freud’s basic schema of the psychosexual stages was modified and refined by Karl Abraham, who further subdivided the phases of libido development, dividing the oral period into a sucking and biting phase, and the anal phase into a defectiveexpulsive (anal sadistic) and a mastering-retaining (anal erotic) phase. Finally, he hypothesized that the phallic period consisted of an earlier phase of pre-genital love, which was designated as the true phallic phase and a later, more mature, genital phase [8]. From the very beginning of the child’s development, Freud regarded the sexual instinct as “anaclitic,” in the sense that the child’s attachment to the feeding and mothering figure is based on the child’s utter physiological dependence on the object [9].

This view of the child’s earliest attachment would seem consistent with Freud’s understanding of infantile libido based on his discovery that sexual fantasies of even adult patients were typically centered on early relationships with their parents. Specifically, he postulated that the choice of a love object in adult life and the love relationship itself were dependent on an important degree on the nature and quality of the child’s object relationships during the earliest years of life [9]. On the other hand, while psychoanalysts generally theorize that paraphilia represent a regression to or a fixation at an earlier level of psychosexual development, resulting in a repetitive pattern of sexual behavior that is not mature in its application and expression [10], behaviorists suggest that the paraphilia begins via a process of conditioning and nonsexual objects can become sexually arousing if they are frequently and repeatedly associated with a pleasurable sexual activity. Anyhow, development of a paraphilia is not usually a matter of conditioning alone; there must usually be some predisposing factor, such as difficulty forming person-to-person sexual relationships or poor self-esteem [11].

Current theories, largely resulting from direct empirical and experimental observations of children in child analyses and developmental studies rather than merely relying on the reconstruction of childhood experiences based on the data from adult analyses, are inclined to focus less on libidinal phase specificity, with the further supposition of programmatic progression of libidinal stages, progressing through the sequence of stages from oral to genital in prescribed order, and place greater emphasis on the complex integration of multiple developmental influences, including maturational factors, temperamental dispositions, object relations involvements and vicissitudes, affective development, cognitive development, language acquisition, and so on [12]. There is accordingly a greater inclination to view libidinal stages as more loosely organized, intermingled, and not necessarily rigidly sequential [13].

Discussion

In the realm of sexual behavior, sex-object is an entity (animate or inanimate, total or in part) that initiates the psychosexual processes and speed up achievement of orgasm, as the final stage of psychosexual excitement, whether in a heterosexual, homosexual or bisexual person or essentially in a person with paraphilia. Typically, and disregard to its known or unknown roots, it has a fixed and specific character, along with subjective significance, in everyone. One of its peculiar characteristics is the obsessed gravity with which it inspires or preoccupies person’s thoughts, usually unintentionally, in reality or imaginarily. Therefore, it has a quality similar to an overvalued idea, not obsessive idea, because it is alloplastic and ego-syntonic and so satisfactory, not ego-dystonic and stressful. Without that and in the realm of sexual activities, fulfilment of orgasm is impossible or so difficult or delayed. In general, it acts as a link between sensual orientation and erotic actions, which can be displaced or substituted according to the psychosexual developmental stages.

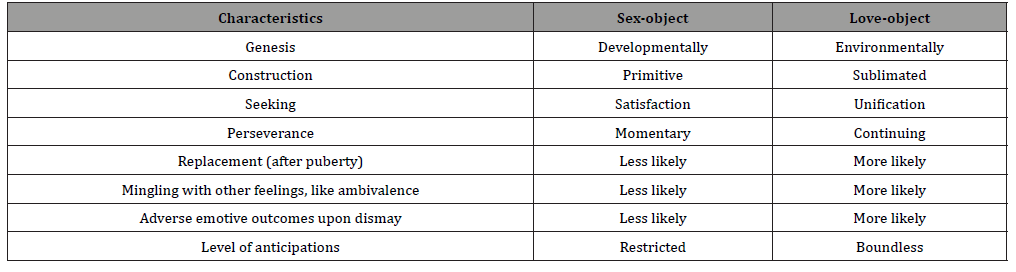

On the other hand, love-object is usually acknowledged by intellectuals and poets in the ground of romance, though many times it may be recognized by people as equal to sex, eroticism or sexual love. It usually pertains to animate people, whether male or female objects, and can be reinforced by sexual performance. It is the main subject of many of novelists or lyricists, who commonly describe love as sublimation of spirits or enhancement of human feelings, a process that starts with the appearance of love-object during social and interpersonal relationships. As like as sex-object, it is also usually an involuntary process and substitutable and may change according to the surroundings and happenings, though with more emotional sequels. For example, in contrary to the first one, it can be mingled with ambivalence or turned more easily into its opposite pole (animosity or hatred), while such a thing is not imaginable with respect to the sex-object, which may stay alive even after changeover (like persistence of masturbation in a married person). Also, love-object can be survived during an apparently asexual route, like a passionate rapport between unconsummated couples, or in spite of presence of sexual dysfunctions (hypoactive sexual desire disorder, sexual aversion disorder, orgasmic disorder, erectile disorder, vaginismus, dyspareunia, etc.). So, while the sex-object is, in general, free from social interactions or external pressures, and totally dependent on internal drives and specific item or process, the love-object is not free from societal communications and surroundings forces (Table 1).

Table 1: Major differences between sex-object and love-object.

In addition, while the sex-object is directly and essentially linked with sexual fulfilments, the love-object may or may not be concluded to sensual accomplishments. Developmentally, while the sex-object may or may not be at the same time a love-object (love object can be in the continuation of sex-object), the love-object can not be anything except than an ultimate item derived from sex-object, though in a more sublimated, less sexualized, and extra spiritualized shape. Persons with paraphilia, like pedophilia, exhibitionism, voyeurism, frotteurism, transvestic fetishism, sexual masochism, sexual sadism, fetishism, and zoophilia, are typically and obsessively in search of erotic gratification and do not feel love towards their favored objects, and after attainment of desired sensual pleasure and orgasm leave them behind easily. Persons with alexithymia or obsessive-compulsive personality traits, as well, usually do not feel love towards others, at least straightforwardly and knowingly (consciously).

But then again, persons who fall in love, habitually, asks for unification and perseverance of relationship and do not tolerate separation effortlessly. Hence, in keeping with the aforesaid facts we may conclude that sex-object and love-object are two unalike items with unalike goal lines. Acknowledgement of this fact by counselor or analyst may help clients, too, to discern these two from each other. For sure, such a distinction may assist patients toward achievement of better insight [14,15] with respect to their judgments, objectrelated conflicts and ambivalences, which possibly will guide their expectations towards more realistic objectives and less bewilderment with respect to their constant displeasures. In this regard, firstly, the partners should have insight regarding their peculiar desires; are they in search of more sexy pleasures or higher sophisticated psychic happiness? Secondly, are their wishes comparable (analogous) to their partner’s cravings? If not, after probing by counselor or psychotherapist, so may they adjust their yearnings accordingly? Thirdly, disregard to plausible genderbased differences that demands specific studies, is principally thorough assimilation of these two possible? Theoretically and evolutionarily it seems conceivable because psychoanalytically and chronologically a direct and continual association between sex-object and love-object is supposable and both of them are end product of sexual instinct; but practically and ultimately it is not so feasible, because historically the sociocultural evolution of human being has been faster or broader than obvious biological evolution [16,17]. Since sexuality, as well, is scientifically a psychosexual process, not simply an organic act, so it is not independent from psychosocial variables [18,19]. Unfortunately, an individual who may not appreciate this point and may not separate different objects from each other may possibly be condemned to feel persistent cheerlessness and in need of recurrent revision concerning the obtainable objects. Auspiciously, the said understanding, disrespect to presumable unconscious origins, is definitely obtainable in the realm of conscious or semi-conscious analysis [20,21].

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shoja Shafti S (2019) Bafflement and Ineffectuality in Apprentices: Indispensible Outcome of Evading Freud and Orthodox Psychoanalysis. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychology Research 3(1): 110-117.

- Shoja Shafti S (2019) Traditionalism and Analytical Thinking: A Potential Incompatibility in Psychoanalysis. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychology Research 3(1): 130-134.

- Person ES, Cooper AM Gabbard GO (2005) Textbook of psychoanalysis.American Psychiatric Publishing Washington, USA.

- Hinshelwood RD (1991) A Dictionary of Kleinian Thought. Free Association Books, London, UK.

- (1999) Attachment research and psychoanalysis. 1. Theoretical considerations. 2. Clinical implications. In: Diamond D, Blatt SJ (eds.), Psychoanal Inquiry 19: 4.

- (2003) Attachment research and psychoanalysis. 3. Further reflections on theory and clinical experience. In: Diamond D, Blatt SJ, Lichtenberg J (eds.), Psychoanalytic Inquiry 23: 1.

- Greenberg JR, Mitchell SA (1983) Object Relations in Psychoanalytic Theory. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, USA.

- Tyson P, Tyson RL (1990) Psychoanalytic Theories of Development. Yale University Press, New Haven, USA.

- Meissner WW (2003) The Ethical Dimension of Psychoanalysis: A Dialogue. State University of New York Press, Albany, USA.

- Briken P, Kafka M (2007) Pharmacological treatments for paraphilic patients and sexual offenders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 20(6): 609-613.

- Kafka M (2012) Axis I psychiatric disorders, paraphilic sexual offending and implications for pharmacological treatment. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 49 (4): 255-261.

- Shapiro T, Emde RN (1993) Research in psychoanalysis: Process, development, outcome. J Amer Psychoan Assn 41(Suppl): 1-424.

- Richards AD, Tyson P (2000) Psychoanalysis, development and the life cycle. J Amer Psychoan Assn 48 (4): 1045-1618.

- Shoja Shafti S (2018) Self-understanding: An analytic end-result of self-absorption. International Journal of Psychoanalysis and Education 10 (1): 61-72.

- Shoja Shafti S (2019) Classical Approach as an Operative Outlet to Clinical Psychoanalysis in Evolving Societies. International Journal of Psychoanalysis and Education 11(1): 5-18.

- Vygotsky LS (1978) Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, USA.

- Shoja Shafti S (2018) Review of Cultural-Historical Psychology. Qoqnoos Publishing Company, Tehran.

- Shoja Shafti S (2003) An Introduction to Sociobiology (Neo-Darwinism). Qoqnoos Publishing Company, Tehran.

- Shoja Shafti S (2016) An Introduction to Clinical Sociobiology: Evolutionary Psychology, Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. Qoqnoos Publishing Company, Tehran.

- Shoja Shafti S (2016) Practicing psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapies in developing societies. American Journal of Psychotherapy 70: 329-342.

- Shoja Shafti S (2018) Psychoanalytic Analysis of Psychopathology. Jami Publishing Company, Tehran.

-

Saeed Shoja Shafti. Love-Object Set Against Sex-Object: Appraising Two Associated Objects. On J Complement & Alt Med. 4(3): 2020. OJCAM.MS.ID.000587.

-

Object; Sex-object; Love-object; Sexuality, Spiritual longings, Psychotherapeutic sessions

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.