Research articles-div

Research articles-div

The Perspective for Luminescent Transition Metalbased Theranostic Probes

Samuel Imeh-Nathaniel1, Emmanuel Imeh-Nathaniel1, Olufeyisayo Odebunmi2, Adeola Olubukola Awujoola2, Patrick Olumuyiwa Sodeke2, Marvin Okon3 and Adebobola Imeh Nathaniel4*

1Riverside High School, USA

2Department of Public Health, East Tennessee State University, USA

3Department of Medicine and Surgery, Obafemi Awolowo University, Nigeria

4Department of Biology, North Greenville University, USA

Adebobola Imeh Nathaniel, Department of Biology North Greenville University, Tigerville South Carolina, USA.

Received Date: January 30, 2020; Published Date: February 11, 2020

Abstract

This study investigates dietary intake between urban and rural secondary school students in a low-income country to provide information on an important target group for dietary interventions. A cross-sectional survey was conducted in a representative sample of 180 senior secondary school classes 1-3(SSS1-SSS3) that comprise of 13–18 years students in the rural and urban areas of Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Student’s t-test was used to compare the average weight of subjects with different age categories in the rural and urban settings, while ANOVA compared different types of dietary intake for breakfast, lunch and dinner and the amount of carbs, protein and fats for the SS1-SS3 classes in urban and rural schools. Dietary intake for carbs, protein and fats for the students in SS1 [F (2, 10) = 61.84, P<0.001], SS2, [F (2, 10) = 113.67, P<0.001] and SS3 [F (2, 10) = 55.32, P <0.001] were significantly different for students in the urban and rural schools. There was no significant difference (P>0.05) for the types of food taken for breakfast, lunch and dinner between the rural and urban schools. Average weight for all age groups were generally higher in the rural schools than the urban schools [T = (1) =4.24, df = 2, P = 0.05)]. Our findings indicate that dietary intake differs in young secondary school students in rural and urban settings. Higher consumption patterns for high starch content root tubers dominated the dietary intake for rural students, while protein and fats were the dominant foods for urban students.

Keywords: Africa, Carbohydrates, Protein, Fats, Diet, Secondary school

Introduction

Dietary food intake is a major risk factor that can be improved to prevent weight gain, improve health and reduce overall disease risk of students irrespective of whether they live in rural or urban setting [1]. Therefore, the assessment of the dietary food intake in both rural and urban secondary school populations provides a holistic assessment of nutrient appropriateness and provides insight into the impact of diet on weight gain and health outcomes [2]. While urban-rural differentials in students’ anthropometric status have been reported in several countries [3-7], little is known about the differences in the dietary intake between urban and rural secondary school students, and especially how these differences may contribute to differences in weight gain. Differences in diet intake between urban and rural secondary school students may reveal differences in the macro or micronutrient consumption patterns, which may show higher carbs, protein or fats intake among rural students. Findings may help to inform the development of targeted programs to improve nutrition in secondary school students to prevent weight gain and reduce the risk for ill health and chronic diseases. Our aim was to assess whether diet quality intake differs between urban and rural secondary school students in a low-income country. We analyzed differences in carbs, protein and fats food intake for breakfast, lunch and dinner and compared weight as an anthropometric measure of the dietary food intake between secondary school students in rural and urban settings. Our findings from the assessment of diet intake in this study population reveal that secondary school students were an important target population for future dietary interventions aiming to improve diet quality.

Method

Area of study

The study was conducted in Ile-Ife located within latitudes 7028 N and 7046 N, and longitudes 4036 E and 4056 E. Ile-Ife is an ancient Yoruba town in southwestern Nigeria. Evidence of Ile- Ife’s urbanization is dated back to 500 AD [8], and it is presently one of the prominent towns in Osun state, extending over parts of Ife Central, Ife East and Ife North Local Government areas with a population of 3501,100 inhabitants((NPC) 2014). The sociocultural group is the Yoruba ethnic group, one of the largest ethnic groups in Africa [9]. Ile-Ife is an agricultural area with a rural setting and inhabitants who are involved in farming of food crops like, yam, cassava, maize, orange, kola, cocoa, vegetables etc.

Data collection

Experimental design: The study consists of students selected from 2 randomly selected secondary schools in urban and rural areas of Ile-Ife. This was a descriptive cross-sectional study on rural and urban secondary school adolescents in South-Western Nigeria. A randomized sampling technique was used to select participants from public secondary schools stratified by rural or urban location. Data were collected from students in Senior secondary school classes 1-3(SSS1-SSS3). Two classes of about 30 students in each were randomly selected (lottery method) from the senior class. In total, 180 secondary school students in the rural and urban areas of Ile-Ife provided complete and useable data for the study.

Sociodemographic characteristics: Questionnaires were administered individually to the students to complete. The respondents were not allowed to fill in the instruments until they clearly understood the procedure. Enough time was allowed for all the respondents to finish. Questionnaires were collected from the students after completion on the spot. Section A of the questionnaire collected data on sociodemographic characteristics, including information on age, gender, household activities, parental occupation and education level. Section B focused on type of food for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Students also completed sections based on the names of local food, which was later categorized to carbohydrate, protein and fats in the data analysis.

Data on anthropometric measurements: We obtained the weight of all the participants before administering the questionnaire. All anthropometric measurements were performed by trained researchers using an electronic scale calibrated prior to weighing [10-13]. The weight was recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg (Tanita WB110AZ). The body mass index (BMI) of each student was calculated as body weight divided by the square of height (kg/m2).

Dietary intake

Dietary intake was measured using a self-administered, semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) for Epidemiological Studies [14]. The FFQ covers at least three types of core food groups including carbohydrate, protein and fats [14]. Participants were asked to answer questions regarding their usual dietary intake for breakfast, lunch and dinner and to indicate how frequently they consumed these foods per day. The FFQ also contained pictures of meals for participants to identify their usual portion size and the food category as carbs, protein or fats which was also included in the final dietary analysis. Dietary intake data were collected and analyzed using standard approach [15].

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted in SPSS 24.0 for Windows. Raw data were used to calculate the descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation). Age groups and average weight of subjects were expressed in percentages to compare urban and rural students. Student’s t-test was used to compare the average weight of subjects in different age categories in the rural and urban settings, while ANOVA compared the types of dietary intake for breakfast, lunch and dinner and the amount of carbs, protein and fats for SS1-SS3 classes in urban and rural schools .

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the institutional review board for Health institutional committee for ethics (approval number: 00052571).

Results

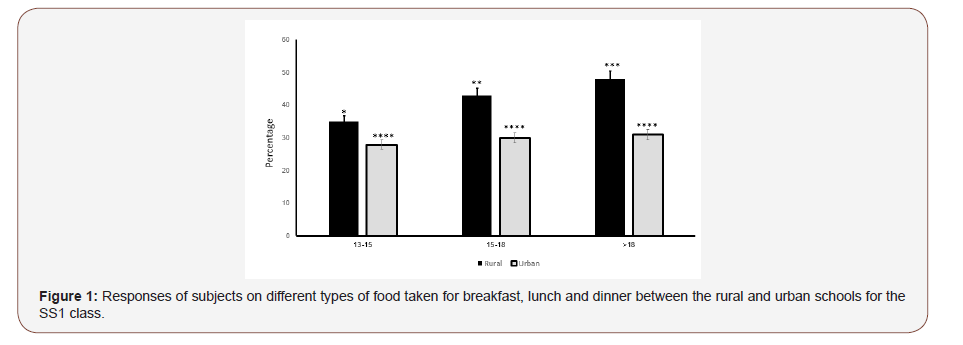

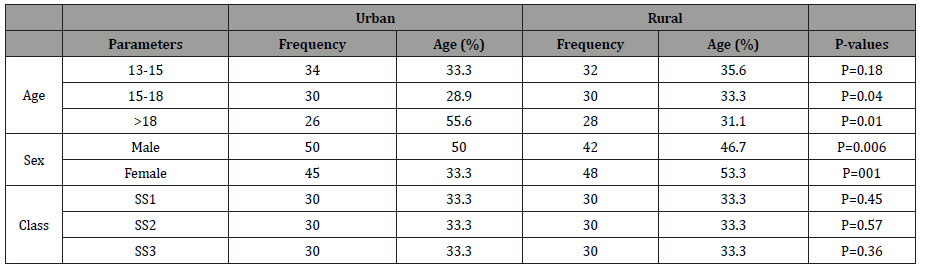

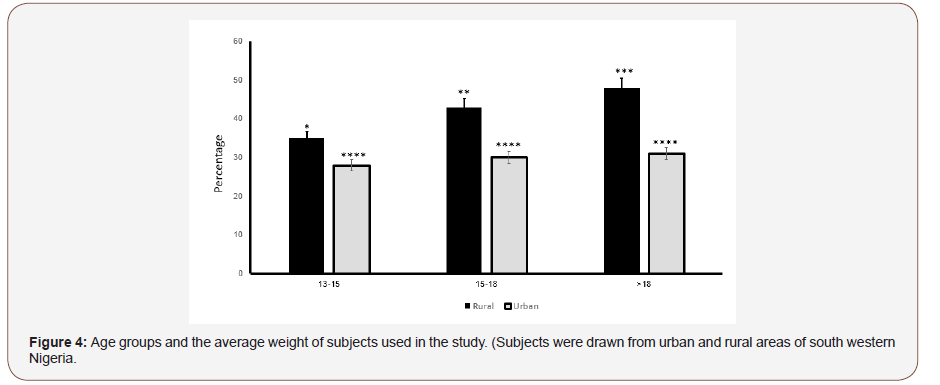

urban schools. The 13-15 age groups were not significantly different between rural and urban schools (P=0.18), the 15-18 (P=0.04). However, the >18 age groups (P=0.01) were significantly different between rural and urban schools. The male (P=0.006) and female (P=0.01) students’ population were significantly different between urban and rural schools, but the different class groups (SSS1-SSS3 were not significantly different (P>0.05) between rural and urban schools. ANOVA found a non-significant difference for the types of food taken for breakfast, lunch and dinner between rural and urban schools [F (5,17) = 0.03, P =0.99], but a significant difference in the intake of carbs, protein and fats for urban and rural schools [F (2,10) = 61.84, P<0.001] for the SS1 class (Figure 1) (Table 1).

Table 1: Table showing the demographic characteristics of respondents in the urban school.

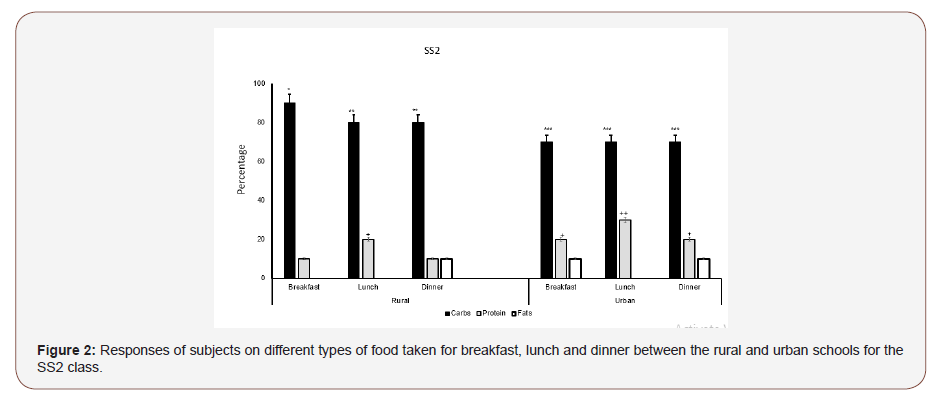

Post-hoc analysis revealed the highest intake of carbs for dinner(P<0.001) was found in students from the rural school, while the highest protein intake was during breakfast for students in the urban school (P<0.001). The highest intake for fats was during lunch and dinner for students the urban school. (P<0.05). For the SS2 (Figure 2), the types of diet for breakfast, lunch and dinner were not significantly different in the urban and rural schools [F (5,17) = 0.05, P =0.85]. There was a significant difference [F (2,10) = 113.67, P<0.001] in the amount of carbs, protein and fats for urban and rural schools. Post-hoc analysis revealed the highest intake of carbs was at breakfast (P<0.001) in the rural school. The highest protein intake was at lunch in the urban school (P<0.001), while the amount of fats was not significantly different (P>0.05) for urban and rural schools.

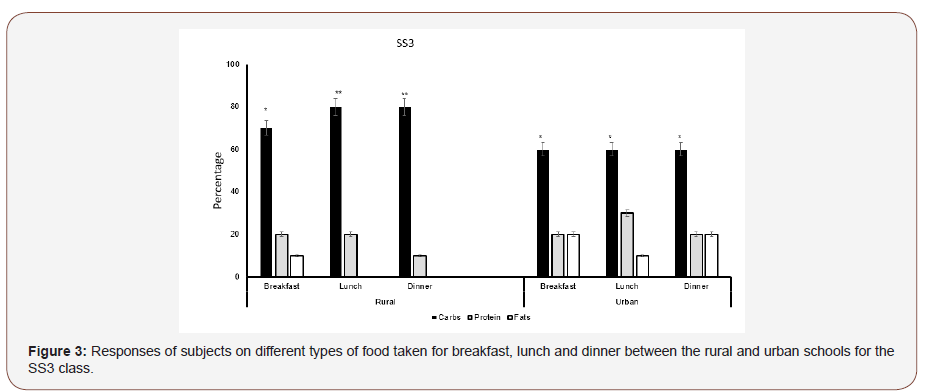

The types of diet for breakfast, lunch and dinner were not significantly different [F (5,17) = 0.05, P=0.21], but the amount of carbs, protein and fats significantly differed [F (2,10) = 55.32, P <0.001] for urban and rural schools of the SS3 class (Figure 3). Post-hoc analysis revealed the highest intake of carbs was at lunch and dinner (P<0.001) in the rural school. The highest protein intake was during lunch in the urban school (P<0.001), while the amount of fats was highest at lunch and dinner (P<0.05) for the urban school. Fig 4 presents the average weight of subjects with different age categories. Students-t-test [ t = (1) =4.24, df = 2, P = 0.05) (Figure 4).

Discussion

The major findings in this study were that, the 15-18, and >18 age groups were significantly different between the rural and urban schools. Also, the male and female student populations were significantly different between urban and rural schools, but the different class groups were not significantly different between the rural and urban schools. Furthermore, there was a significant difference in the intake of carbs, protein and fats for urban and rural schools for the SSS1-SSS3 classes during breakfast, lunch and dinner. Finally, the average weight for all age groups was generally higher in the rural schools than the urban schools. Different types of dietary intake have a strong effect on students’ weight [16- 20] and can be analyzed to assess changes in the urban-rural differentials in diet and weight in different populations. In this study, we observed a general high intake of carbs for breakfast, lunch and dinner for students in the rural school compared to students in the urban school. The highest intake for protein and fats-rich food was observed at lunch and dinner for students in the urban schools. This finding identifies heavy starchy root tuber carbs as the major dietary intake for rural school students while protein and low amount of fats constitute the major dietary intake for urban students. This reveals that differences exist in diet quality among students in urban and rural settings. Although the type of diet (carbs, protein and fats) did not differ in urban and rural students, a higher macronutrient consumption pattern was related to a higher starchy root tuber carbohydrate dominated by cassava, plantain and yam flour in rural students. Our finding is supported by other recent studies [21-26], suggesting that different strategies are needed in rural and urban areas to identify and improve healthy dietary intake for populations at risk of diet-related diseases.

It is well known that fat is far more efficient at expanding fat store than protein or carbohydrate [27]. The estimated metabolic cost of storing carbohydrate as body fat requires 23% of its energy content as opposed to 3% for dietary fat [27]. It then implies that if the body’s metabolism remains constant, it is very likely that specific sources of energy in the diet may differentially affect weight gain [28]. Hence, suggesting that dietary fat may be associated with obesity independent of the energy intake [29]. Other recent studies have identified that different levels of carbohydrate in the diet could prevent metabolic changes from occurring [30-33], such that weight loss may be prevented. Highly processed carbohydrates like refined breads, crackers, cookies, and sugars cause energy from the food to be stored more easily as fat, and may increase hunger and food cravings, lower energy expenditure, and promote weight gain [30]. While the simple act of eating carbohydrates does not cause weight gain, eating too much carbohydrate or fat or protein can lead to weight gain [34]. The consumption of excessive amount of carbohydrates is converted to fat and stored in adipose tissue through lipogenesis, resulting in weight gain [35,36]. In our study, it can be inferred that the high intake of heavy starchy root tuber carbs among rural school students resulted in excess circulating glucose. This is converted to triglycerides and stored in adipose tissue resulting in more weight gain in rural students compared to those in urban schools who had a balanced amount of carbs, protein and fats.

Diet is one risk factor that can be modified to prevent weight gain, improve health and reduce overall disease risk [1]. Assessing dietary intake in this study involving student populations provides a holistic assessment of nutrient adequacy, which provides insight on the impact of diet quality on weight gain [2]. Existing studies have measured diet quality in younger, reproductive aged women and studies in higher-risk settings including rural populations, compared to urban settings. Some findings reveal better diet quality in urban population compared to their rural counterparts [37,38], while others report insignificant differences [39,40]. In a population of rural and urban secondary school students with different socioeconomic environment, our findings indicate starchy carbs as the major dietary intake for rural school students while protein and low amount of fats constitute the major dietary intake for urban students revealing differences in diet quality among students in urban and rural settings. Moreover, the average weight for all age groups was generally higher in the rural school than the urban school. Findings suggest improvement of students’ nutrition in the rural setting which would close the urban-rural gap in nutritional status of secondary school students [41,42].

Conclusion

Our results show that the diet intake did not differ in urban and rural students; however, a higher macronutrient consumption pattern was potentially related to a higher starchy root tuber carbohydrate dominated by cassava, plantain and yam flour in rural students. Differences between developed and developing countries may, in part, account for the differences reported. These findings reveal that dietary intake differs in young secondary school students in the rural and urban settings. This assessment of dietary intake in rural and urban student populations may better inform the development of targeted weight gain prevention programs for secondary school students in rural areas of low-developing countries.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Pedroza Tobias AL, Hernandez Barrera N, Lopez Olmedo A, Garcia Guerra S, Rodriguez Ramirez I, et al. (2016) Usual Vitamin Intakes by Mexican Populations. J Nutr 146(9): 1866-1873.

- Bojar I, Owoc A, Humeniuk E, Fronczak A, Walecka I (2014) Quality of pregnant women's diet in Poland-macro-elements. Arch Med Sci 10(2): 361-365.

- Ervin PA, Bubak V (2019) Closing the rural-urban gap in child malnutrition: Evidence from Paraguay, 1997-2012. Econ Hum Biol 32: 1-10.

- Liu H, Fang H, Zhao Z (2013) Urban-rural disparities of child health and nutritional status in China from 1989-2006. Econ Hum Biol 11(3): 294-309.

- Liu H, Rizzo JA, Fang H (2015) Urban-rural disparities in child nutrition-related health outcomes in China: The role of hukou policy BMC Public Health 15: 1159.

- Sharaf MF, Mansour EI, Rashad AS (2019) Child nutritional status in egypt: a comprehensive analysis of socioeconomic determinants using a quantile regression approach. J Biosoc Sci 51(1): 1-17.

- Zhang N, Becares L, Chandola T (2016) Patterns and Determinants of Double-Burden of Malnutrition among Rural Children: Evidence from China. PLoS One 11(7): e0158119.

- Mabogunje A (1968) Urbanization in Nigeria. University of London Press, London.

- Adedini SA, Odimegwu C, Imasiku ENS, Ononokpono DN (2015) Ethnic differentials in under-five mortality in Nigeria. Ethn Health 20(2): 145-162.

- Cuttler R, Evans R, McClusky E, Purser L, Klassen KM, et al. (2019) An investigation of the cost of food in the Geelong region of rural Victoria: Essential data to support planning to improve access to nutritious food. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 30(1): 124-127.

- Palermo C, McCartan J, Kleve S, Sinha K, Shiell A (2016) A longitudinal study of the cost of food in Victoria influenced by geography and nutritional quality. Aust N Z J Public Health 40(3): 270-273.

- Rossimel A, Han SS, Larsen K, Palermo C (2016) Access and affordability of nutritious food in metropolitan Melbourne. Nutrition & Dietetics 73(1): 13-18.

- Williams P (2010) Monitoring the Affordability of Healthy Eating: A Case Study of 10 Years of the Illawarra Healthy Food Basket. Nutrients 2(11): 1132-1140.

- Ashton MM, Dean OM, Marx WG, Mohebbi M, Berk M, et al. (2020) Diet quality, dietary inflammatory index and body mass index as predictors of response to adjunctive N-acetylcysteine and mitochondrial agents in adults with bipolar disorder: A sub-study of a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 54(2): 159-172.

- Cantoni M, Paffenbarger RS, Krueger DE (1961) Methods of dietary assessment in current epidemiologic studies of cardiovascular diseases. Am J Public Health Nations Health 51: 70-75.

- Blaine RE, Kachurak A, Davison KK, Klabunde R, Fisher JO (2017) Food parenting and child snacking: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 14(1): 146.

- Burnett AJ, Worsley A, Lacy KE, Lamb KE (2019) Moderation of associations between maternal parenting styles and Australian pre-school children's dietary intake by family structure and mother's employment status. Public Health Nutr 22(6): 997-1009.

- Haines J, Haycraft E, Lytle L, Nicklaus S, Kok FJ, et al. (2019) Nurturing Children's Healthy Eating: Position statement. Appetite 137: 124-133.

- Llanaj E, Adany R, Lachat C, Haese MD (2018) Examining food intake and eating out of home patterns among university students. PLoS One 13(10): e0197874.

- Scaglioni S, Cosmi De V, Ciappolino V, Parazzini F, Brambilla P, et al. (2018) Factors Influencing Children's Eating Behaviours. Nutrients 10(6): E706.

- Choy CC, Desai MM, Park JJ, Frame EA, Thompson AA, et al. (2017) Child, maternal and household-level correlates of nutritional status: a cross-sectional study among young Samoan children. Public Health Nutr 20(7): 1235-1247.

- Kosaka S, Suda K, Gunawan B, Raksanagara A, Watanabe C, et al. (2018) Urban-rural difference in the determinants of dietary and energy intake patterns: A case study in West Java, Indonesia. PLoS One 13(5): e0197626.

- Liu HQ, Hall JJ, Xu XY, Mishra GD, Byles JE (2018) Differences in food and nutrient intakes between Australian- and Asian-born women living in Australia: Results from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health. Nutr Diet 75(2): 142-150.

- Mattei J, Malik V, Wedick NM, Hu FB, Spiegelman D, et al. (2015) Reducing the global burden of type 2 diabetes by improving the quality of staple foods: The Global Nutrition and Epidemiologic Transition Initiative. Global Health 11: 23.

- Sievert K, Lawrence M, Naika A, Baker P (2019) Processed Foods and Nutrition Transition in the Pacific: Regional Trends, Patterns and Food System Drivers. Nutrients 11(6): E1328.

- Zeba AN, Yameogo MT, Tougouma SJB, Kassie D, Fournet F (2017) Can Urbanization, Social and Spatial Disparities Help to Understand the Rise of Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Bobo-Dioulasso? A Study in a Secondary City of Burkina Faso, West Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(4): E378.

- Galgani J, E Ravussin (2008) Energy metabolism, fuel selection and body weight regulation. Int J Obes (Lond) 32: 109-119.

- Doucet E, Tremblay A (1997) Food intake, energy balance and body weight control. Eur J Clin Nutr 51(12): 846-855.

- Mendoza JA, Drewnowski A, Christakis DA (2007) Dietary energy density is associated with obesity and the metabolic syndrome in US adults. Diabetes Care 30(4): 974-979.

- Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Klein GL, Wong JMW, Bielak V, et al. (2018) Effects of a low carbohydrate diet on energy expenditure during weight loss maintenance: randomized trial. BMJ 14: 363.

- Martens EA, Gonnissen HK, Gatta Cherifi B, Janssens PL, Westerterp Plantenga MS (2015) Maintenance of energy expenditure on high-protein vs. high-carbohydrate diets at a constant body weight may prevent a positive energy balance. Clin Nutr 34(5): 968-975.

- Veldhorst MA, Westerterp KR, Van Vught A, Westerterp Plantenga MS (2010) Presence or absence of carbohydrates and the proportion of fat in a high-protein diet affect appetite suppression but not energy expenditure in normal-weight human subjects fed in energy balance. Br J Nutr 104(9): 1395-1405.

- Westerterp Plantenga MS, Lemmens SG, Westerterp KR (2012) Dietary protein - its role in satiety, energetics, weight loss and health. Br J Nutr 108: S105-112.

- Hall KD, Ayuketah A, Brychta R, Cai HY, Cassimatis T, et al. (2019) Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake. Cell Metab 30(1): 67-77.

- Bartelt A, Weigelt C, Cherradi ML, Niemeier A, Thodter K, et al. (2013) Effects of adipocyte lipoprotein lipase on de novo lipogenesis and white adipose tissue browning. Biochim Biophys Acta 1831(5): 934-942.

- Grobe JL, Venegas Pont M, Sigmund CD, Ryan MJ (2009) PPAR gamma differentially regulates energy substrate handling in brown vs. white adipose: focus on "The PPAR gamma agonist rosiglitazone enhances rat brown adipose tissue lipogenesis from glucose without altering glucose uptake. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 296(5): R1325-R1326.

- Potter JL, Collins CE, Brown LJ, Hure AJ (2014) Diet quality of Australian breast cancer survivors: a cross-sectional analysis from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health. J Hum Nutr Diet 27(6): 569-576.

- Tsigga M, Filis V, Hatzopoulou K, Kotzamanidis C, Grammatikopoulou MG (2011) Healthy Eating Index during pregnancy according to pre-gravid and gravid weight status. Public Health Nutr 14(2): 290-296.

- Gardner CD (2019) Preventing weight gain more important than weight loss and more realistic to study in cohorts than in randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr 110(3): 544-545.

- Lombard CB, Harrison CL, Kozica SL, Zoungas S, Keating C, et al. (2014) Effectiveness and implementation of an obesity prevention intervention: The HeLP-her Rural cluster randomised controlled trial.” BMC Public Health 14: 608.

- (NPC) NPC (2014) [Nigeria] 2006 Population and Housing Census of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. Abuja, Nigeria: National Population Commission; 2006.” NPC (2): 236-651.

- Kaviani S, Van Dellen M, Cooper JA (2019) Daily Self-Weighing to Prevent Holiday-Associated Weight Gain in Adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 27(6): 908-916.