Research Article

Research Article

Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Managing Chronic Pain and Preventing Analgesic Misuse in the Community

Feng Feng1*, April Horstman-Reser2, Jeanine Kernen3, Dean Manternach4, Harsha Sharma5 and Courtney Caron6

1Arts and Sciences Division, Nebraska Methodist College, 720 North 87th Street, Omaha, Nebraska 68114.

2Arts and Sciences Division, Nebraska Methodist College, 720 North 87th Street, Omaha, Nebraska 68114

3Arts and Sciences Division, Nebraska Methodist College, 720 North 87th Street, Omaha, Nebraska 68114.

4Arts and Sciences Division, Nebraska Methodist College, 720 North 87th Street, Omaha, Nebraska 68114.

5Arts and Sciences Division, Nebraska Methodist College, 720 North 87th Street, Omaha, Nebraska 68114.

6Student, Nebraska Methodist College, 720 North 87th Street, Omaha, Nebraska 68114.

Dr Feng Feng, Arts and Sciences Division, Nebraska Methodist College, 720 North 87th Street, Omaha, Nebraska 68114, USA.

Received Date: October 22, 2020; Published Date:January 05, 2021

Abstract

Background: Chronic pain is one of the top causes of disability in the US. Repeated use and large dosages of analgesic medications increase the risks of side effects, misuse, and dependency. When the pain control cannot be achieved at a satisfactory level, patients may seek complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). There is a dearth of evidence-based practice research showing the effectiveness of CAM in reducing analgesic use.

Objective: This pilot study provides evidence to increase awareness of CAM to improve community health and offers nonpharmacological interventions in pain management along with the prevention of analgesic misuse.

Methodology: This quantitative research recruited 16 participants in an underserved community in Omaha for phase I sampling, 15 participants for beginning of phase II sampling. The participants from phase I received an education session and completed a survey. Phase II participants received six sessions of CAM education and treatments. The attitude, knowledge level, pain scores, and analgesics usages were collected and analyzed after six sessions.

Results: Most health issues likely to be addressed with CAM were chronic pain. Participants increased communication about CAM practice with their providers after completion of phase II. Participants overall pain score and analgesics usage significantly decreased after six weeks of CAM education and treatment.

Conclusion: After six sessions of CAM education and treatments, participant pain level and analgesic usage decreased significantly. This study is a good example of a successful intervention in an underserved community population about the effectiveness of CAM approaches on chronic pain and analgesic misuse management.

Keywords:Complementary and alternative medicine, chronic pain, analgesic use

Introduction

Chronic pain, one of the leading causes of disability, affects populations across the world. There are 20.4% (50 million) of US adults with chronic pain and 8% (19.6 million) of US adults with high-impact chronic pain according to Center for Disease Control and Prevention [1]. Most patients in the US who complain about low back pain, headache, and neck pain are initially managed by the over the counter NSAIDS. However, the modalities are quickly switched to opioids, skeletal muscle relaxants, antidepressants, membrane stabilization agents, and benzodiazepine [2]. The greatly increased medical care cost and lost productivity affect populations in chronic pain. Weeks has advocated to provide insurance coverage of nonpharmacologic approaches to manage pain, and better deal with the opioid crisis [3]. Despite advanced pharmacological interventions, many patients continue to deal with ongoing pain that is not fully addressed by the medication offered to them. Meanwhile, increased risk of adverse effects, analgesic misuse, and opioid abuse become an epidemic issue around the nation. The interest in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among patients is high, and the number of effective treatments available for chronic pain are few [4-7]. More than 30% of adults and about 12% of children in the U.S. use CAM. CAM is defined as a non-mainstream practice used together with conventional medicine (complementary medicine), or in place of conventional medicine (alternative medicine) [8]. There are three major types of CAM being widely used in modern medical practice: natural products, manual healing, and mind, body, and spirit practices. Other complementary approaches also have been used such as Ayurvedic medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, homeopathy, and naturopathy [8]. There are limited evidence-based CAM treatments that have been adequate in controlling chronic pain, but not much on analgesic reduction [9] (Table 1).

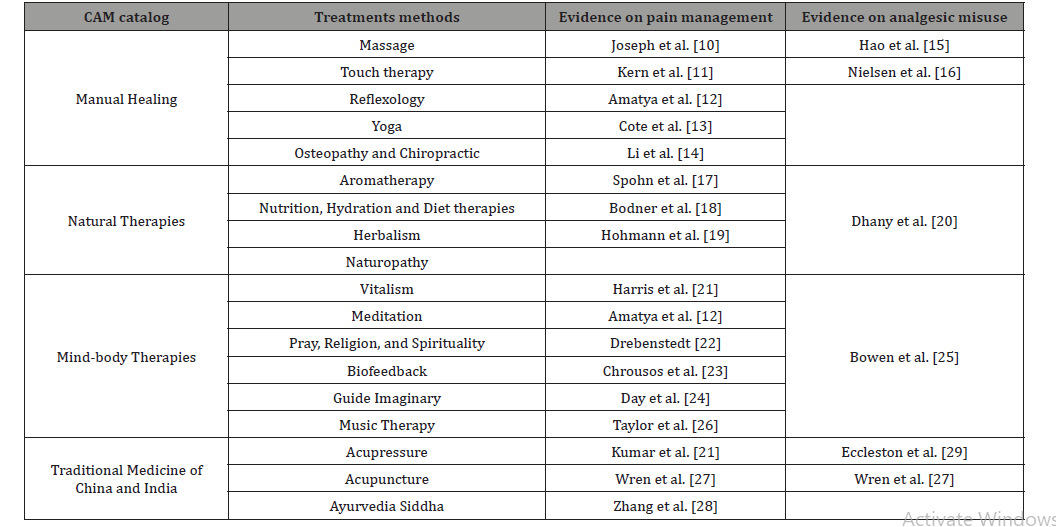

Table 1: Systemic review on CAM for chronic pain management and analgesic misuse.

Summarizes most of CAM modalities used for chronic pain management and analgesic misuse prevention. Our study provides an evaluation of the effectiveness and limitations of CAM treatments in the prevention and treatment of chronic pain and analgesic reduction.

Methods

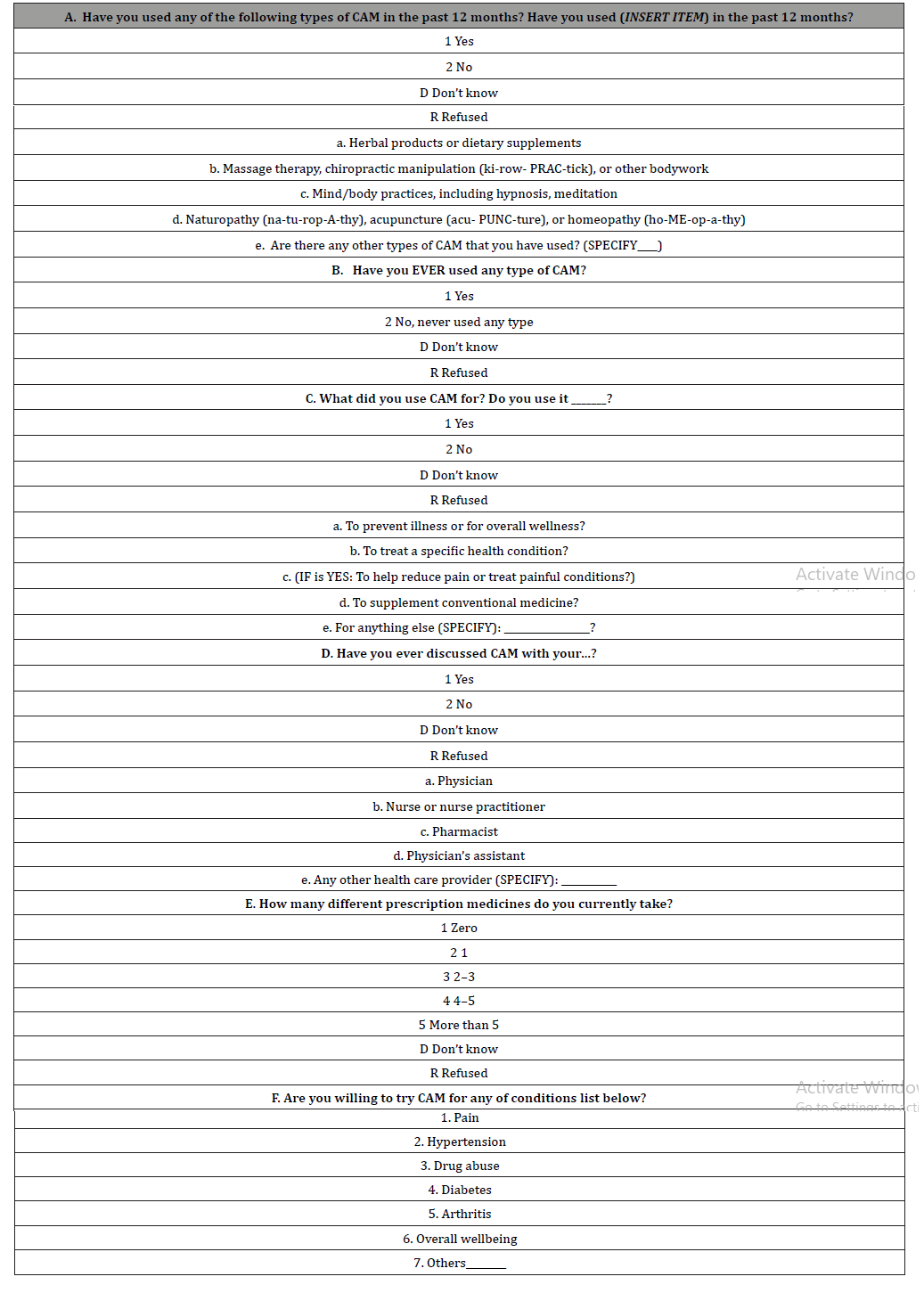

Table 2: Survey questions for phase I.

This study was designed as comparative, community-based participatory research. The study was performed at In Common Development Community in Omaha, NE, between December 2018 and March 2019. In Common Development Community is a midtown community with a large Hispanic and low-income population. There were two phases in this study. In phase I, we offered a presentation of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use for the low-income US adults. All participants from age 19-90 years old were welcome and completed an anonymous survey to identify CAM approaches being used among this population. Concurrently, we investigated current chronic pain and analgesic use in this group (Table 2).

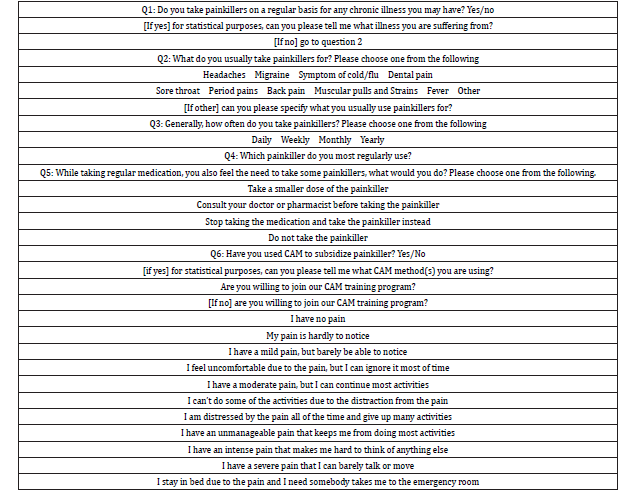

The response rate was 100% resulting in a total of 16 participants (n=16). Phase II started with a recruited group of 15 participants given written informed consent before the inclusion. Inclusion criteria were participants who have experienced chronic pain with using analgesics on a regular basis. The numerical rating pain scale and an anonymous questionnaire administered to 15 qualified participants is shown in (Table 3) (n=15).

Table 3: Phase II pre-and post-questionnaire and scale of pain severity.

All participants then received six sessions of education and treatments on the following: acupressure, guided imagery, music therapy, aromatherapy, Yoga, diet, hydration and supplemental vitamins, reflexology, biofeedback, meditation, and prayer approaches. The same questionnaire and numerical rating pain scale were re-measured after completion of six sessions. The response rate of phase II was 73% resulting in a total of 11 participants completing the study (n=11). The Institutional Review Board of Nebraska Methodist College approved all procedures. Inform consent forms were reviewed and signed by all participants at the beginning of Phase II.

Data analysis

Feedback from phase I and phase II was elicited, and Fisher’s exact and two-tail t-tests were used to examine differences in responses of pre- and post-treatment/education on phase II data.

Results and Discussion

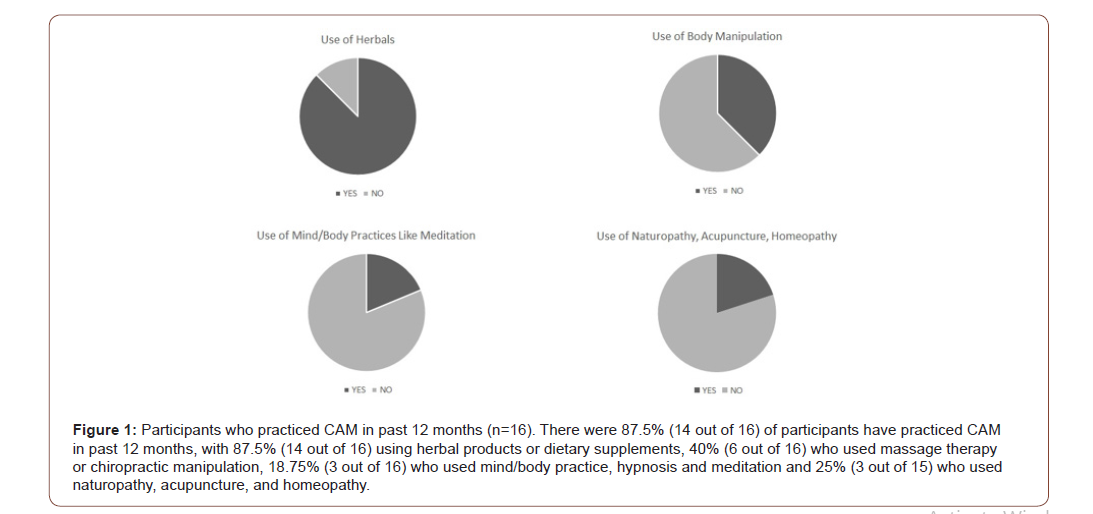

Analgesics are widely used to treat chronic pain, but may lead to misuse, side effects and dependency. When CAM therapies have been accepted among the chronic pain population, the implementation, consistency and techniques are not always addressed. Therefore, there is not adequate evidence on the effectiveness of CAM’s impact on chronic pain and analgesic reduction. Our project started with a general questionnaire asking about attitudes of CAM use and knowledge level of CAM and analgesic use. In our sample, 87.5% (14 out of 16) of participants have practiced CAM in past 12 months, with 87.5% (14 out of 16) using herbal products or dietary supplements, 40% (6 out of 16) who used massage therapy or chiropractic manipulation, 18.75% (3 out of 16) who used mind/ body practice, hypnosis and meditation and 25% (3 out of 15) who used naturopathy, acupuncture, and homeopathy (Figure 1).

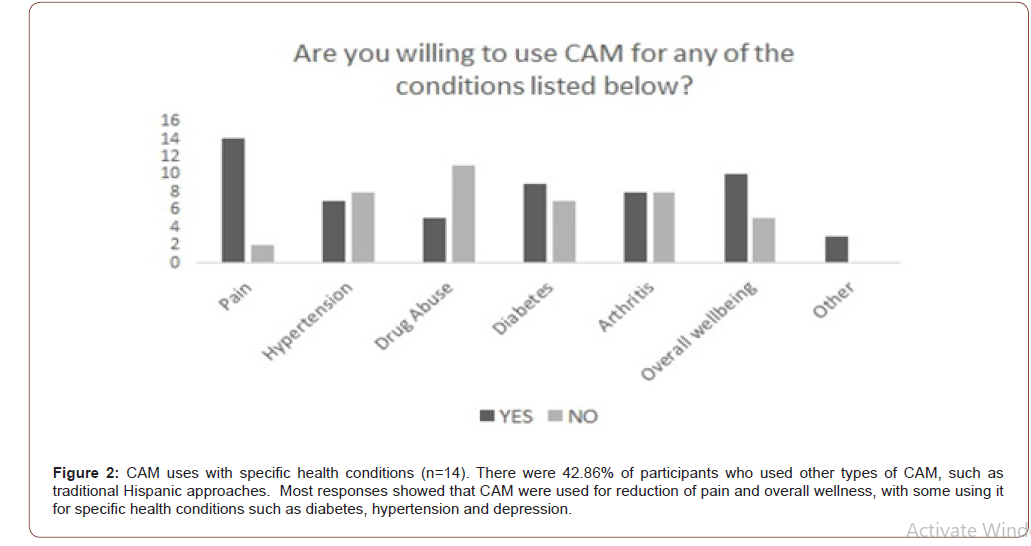

There were 42.86% of participants who used other types of CAM, such as traditional Hispanic approaches. Most responses showed that CAM were used for reduction of pain and overall wellness, with some using it for specific health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and depression (Figure 2).

These data lined up with the previous research findings that CAM has been used in place of traditional therapies, especially on pain management [9,30].

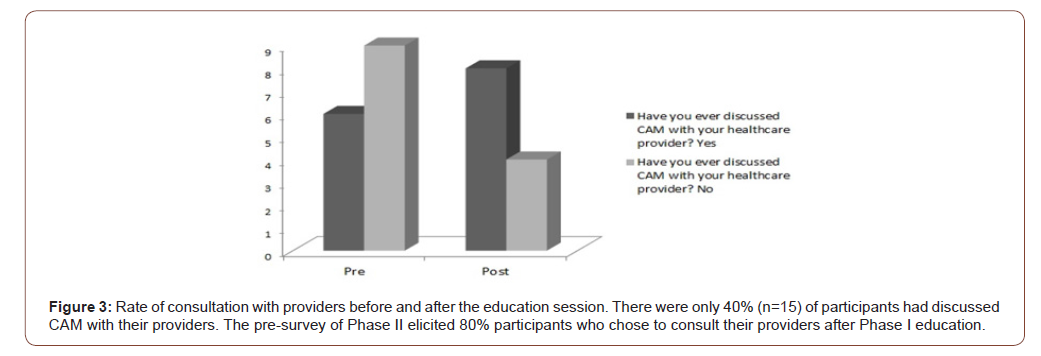

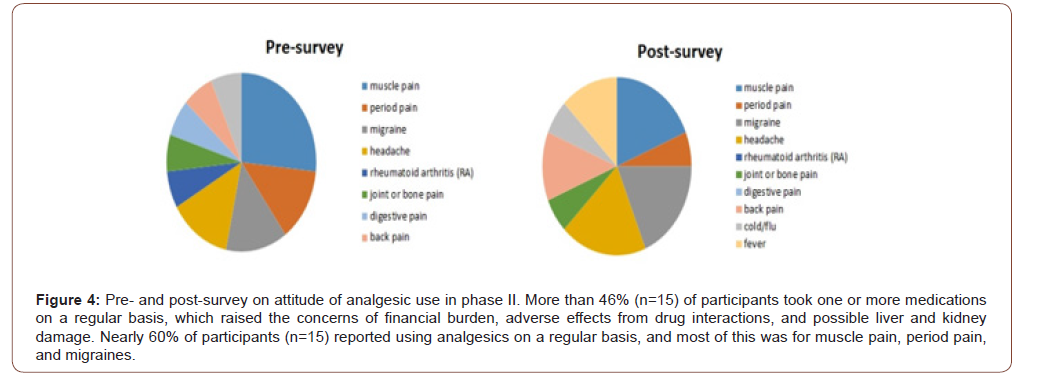

It has been an issue that patients do not discuss their CAM use with health providers. Our data showed that only 40% (6 out of 15) of participants had discussed CAM with their providers. However, the data from the pre-survey of Phase II elicited 80% participants who chose to consult their providers after Phase I education (Figure 3). More than 46% (7 out of 15) of participants took one or more medications on a regular basis, which raised the concerns of financial burden, adverse effects from drug interactions, and possible liver and kidney damage (Figure 4).

Although many patients accept CAM concepts and approaches, and often practice CAM on their own, the health provider should be the first one to educate the patient and guide them. Our education sessions addressed the importance of communications between patients and providers to evaluate risks and benefits, and ultimately to guide patients in making evidence-based, well informed decisions about whether to use such therapies.

Our data reported that most of participants in phase I were interested in trying CAM for pain control, hypertension, drug abuse, diabetes, arthritis, and overall wellbeing (Figure 2). All these participants were invited for the phase II study. Even though a CAM therapy has a limited evidence of efficacy on chronic pain management in publications, we believe patients can still improve their daily life quality as well as the increased knowledge of untapped potential benefits with its use. A new theory would elicit a collaborative framework combining evidence-based CAM with modern medicine that derives the benefits of a healing context, ritual, and interpersonal expectations in response to treatments [30]. Therefore, the attitude of acceptance of CAM integration may help to refine the patient’s treatments and outcomes.

Nearly 60% of participants in phase II (9 out of 15) reported using analgesics on a regular basis, and most of this was for muscle pain, period pain, and migraines. However, analgesics are broadly taken for any type of pain, but no fever as shown by the data (Figure 4). Among nine participants who took the analgesic on a regular basis, three of them took it daily, three of them took it weekly, and another three took it monthly. The medications that have been taken by the group vary, such as Ibuprofen, Aspirin, Tylenol, Codeine and Diclofenac. Our data surprisingly show that four participants took Codeine, and two participants took Diclofenac on a regular basis.

The opioid epidemic is increasing due to opioid prescription, and related misuse, abuse, and resultant death in the United States [31]. Even the acetaminophen misuse rate is increasing in our society [32]. The effort to decrease analgesic misuse without compromising pain management is a challenge for both practitioners and patients.

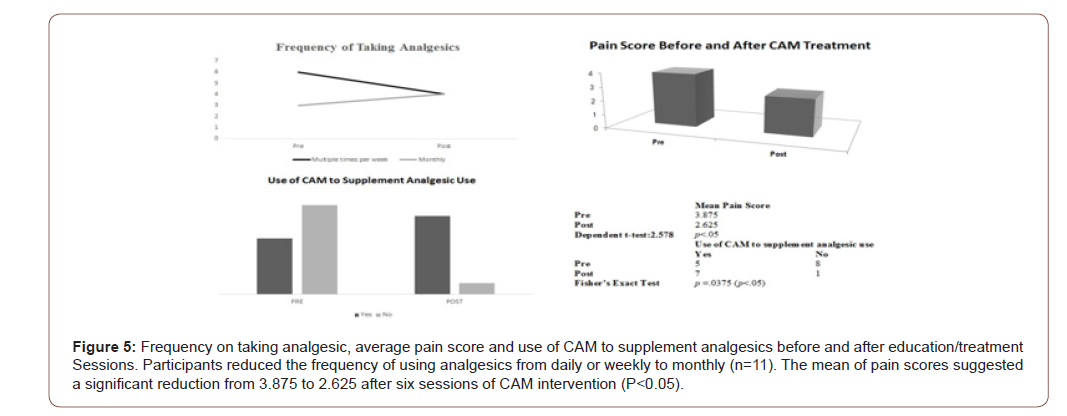

The post-survey data demonstrated that the participants still took analgesics for chronic pain; however, the increased usage on the chart was for fever (Figure 5). The significant change was frequency of analgesics taken from pre to post data; the participants reduced the analgesic usage after six sessions of CAM treatment and education. The data suggested that some participants reduced the frequency of using analgesics from daily or weekly to monthly (Figure 5). The mean of pain scores suggested a significant reduction from 3.875-2.625 after six sessions of CAM intervention (Figure 5). Meanwhile, use of CAM to supplement analgesic use after training has been significantly increased (Figure 5). The results shed light on CAM potential positive effects on chronic pain management and further limiting analgesic misuse that were found in some research [13,16,27].

Herbal or dietary supplements, massage therapy, or other manipulation were identified as the most frequently used modalities on all participants (Figure 1) before and after the training. Herbal and dietary supplements, as well as massage, are easy to practice at home and well accepted by the participants in our sample. Many other types of CAM practice are still considered an obstacle for communities, especially the underserved population.

Limitation

There were limitations with this quantitative research. Although every rigorous recruiting effort was made, it was challenging for participants to attend all the six sessions due to personal reasons; in phase II the number of participants dropped to eight. In some instances, participants did not answer all the questions on the questionnaire since the surveys are anonymous. In addition, there is no control group being selected; however, the data provide valuable insights into CAM approaches that added to modern medicine improve chronic pain management and prevention of analgesic misuse.

Conclusion

Overall, our findings contribute to the growing body of literature exploring the role of CAM on chronic pain management and analgesic misuse prevention. We ascertain that this underserved community gained knowledge and positive attitude after CAM training. The education provided benefited them well as evident by implementation of CAM approaches. After the sessions, the participants realized the importance of communication with their providers, and the risk and benefits before and after they adopt CAM. After six sessions of CAM education and treatments, participant pain level and analgesic usage decreased significantly. The outcomes of this study are a good example of a successful intervention in an underserved community population that contribute to the debate about the effectiveness of CAM approaches on chronic pain and analgesic misuse management.

Implications and future directions

After reviewing the research database, there is a clear indication that little is known about CAM approaches on chronic pain management, especially on analgesic misuse prevention among underserved communities. The plan is to recruit more community partners and increase the study sample size for future research study. In addition, we will still use these multidomain strategies as an intervention tool. However, we will add more strategies to assess the relationship between the use of each modality and its outcome, and as well as to identify the best modalities.

Acknowledgement

Methodist Foundation provided grant funds to initiate the research.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, Nahin R, Mackey S, et al. (2018) Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults United States 2016. 67(36): 1001-1006.

- Hsu E (2017) Medication overuse in chronic pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep 21(1): 2.

- Weeks J (2016) Influential U.S. Medical Organizations Call for Insurance Coverage of Non-Pharmacologic Approaches to Pain. J Altern Complement Med 22(12): 947-949.

- Hart J, Pastore G, Jones M, Barker A, Khosa J, et al. (2016) Chronic orchialgia after surgical exploration for acute scrotal pain in children. J Pediatr Urol 12(3): 168.

- Penney LS, Ritenbaugh C, Elder C, Schneider J, Deyo RA, et al. (2016) Primary care physicians, acupuncture and chiropractic clinicians, and chronic pain patients: a qualitative analysis of communication and care coordination patterns. BMC Complement Altern Med 16: 30.

- Chou L, Ranger TA, Peiris W, Cicuttini FM, Urquhart DM, et al. (2018) Patients' perceived needs for medical services for non-specific low back pain: A systematic scoping review. PLoS One 13(11): e0204885.

- Teut M, Ullmann A, Ortiz M, Rotter G, G Rotter, et al. (2012) Pulsatile dry cupping in chronic low back pain a randomized three-armed controlled clinical trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 18(1): 115.

- (2017) NCCIH. Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What is in a Name?

- Hamlin AS, Robertson TM (2017) Pain and Complementary Therapies. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 29(4): 449-460.

- Joseph LH, Hancharoenkul B, Sitilertpisan P, Pirunsan U, Paungmali A (2018) Effects of Massage as a Combination Therapy with Lumbopelvic Stability Exercises as Compared to Standard Massage Therapy in Low Back Pain: a Randomized Cross-Over Study. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork 11(4): 16-22.

- Kern C, McCoart A, Beltranm T, Martoszek M (2018) The Benefits of Reflexology for the Chronic Pain Patient in a Military Pain Clinic. J Spec Oper Med 18(4): 103-105.

- Amatya B, Young J, Khan F (2018) Non-pharmacological interventions for chronic pain in multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12(12): CD012622.

- Côté P, Yu H, Shearer HM, Randhawa K, Wong JJ, et al. (2019) Non-pharmacological management of persistent headaches associated with neck pain: A clinical practice guideline from the Ontario protocol for traffic injury management (OPTIMa) collaboration. Eur J Pain 23(6): 1051-1070.

- Li Y, Li S, Jiang J, Sue Yuan (2019) Effects of yoga on patients with chronic nonspecific neck pain: A PRISMA systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 98(8): e14649.

- Hao J, Lucido D, Cruciani RA (2014) Potential impact of abrupt opioid therapy discontinuation in the management of chronic pain: a pilot study on patient perspective. J Opioid Manag 10(1): 9-20.

- Nielsen S, Campbell G, Peacock A, Smith K, Bruno R, et al. (2016) Health service utilization by people living with chronic non-cancer pain: findings from the Pain and Opioids IN Treatment (POINT) study. Aust Health Rev 40(5): 490-499.

- Spohn D, Musial F, Rolke R (2013) Naturopathic reflex therapies for the treatment of chronic pain - Part 2: Quantitative sensory testing as a translational tool. Forsch Komplementmed 20(3): 225-230.

- Bodner K, D’Amico S, Luo M, Sommers E, Goldstein L, et al. (2018) A cross-sectional review of the prevalence of integrative medicine in pediatric pain clinics across the United States. Complement Ther Med 38: 79-84.

- Hohmann CD, Stange R, Steckhan N, Robens S, Ostermann T, et al. (2018) The Effectiveness of Leech Therapy in Chronic Low Back Pain. Dtsch Arztebl Int 115(47): 785-792.

- Dhany AL, Mitchell T, Foy C (2012) Aromatherapy and Massage Intrapartum Service Impact on Use of Analgesia and Anesthesia in Women in Labor: A Retrospective Case Note Analysis. J Altern Complement Med 18(10): 932-938.

- Harris JI, Usset T, Krause L, Schill D, Reuer B, et al. (2018) Spiritual/Religious Distress Is Associated with Pain Catastrophizing and Interference in Veterans with Chronic Pain. Pain Med 19(4): 757-763.

- Drebenstedt C (2018) Nonpharmacological pain therapy for chronic pain. Z Gerontol Geriatr 51(8): 859-863.

- Chrousos GP, Boschiero D (2019) Clinical validation of a non-invasive electrodermal biofeedback device useful for reducing chronic perceived pain and systemic inflammation. Hormones (Athens) 18(2): 207-213.

- Day MA, Ward LC, Ehde DM, Thorn BE, Burns J, et al. (2019) A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Mindfulness Meditation, Cognitive Therapy, and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain. Pain Med 20(11): 2134-2148.

- Bowen S, Somohano VC, Rutkie RE, Jacob A Manuel, Kristoffer L (2017) Rehder Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention for Methadone Maintenance: A Feasibility Trial. J Altern Complement Med 23(7): 541-544.

- Taylor SL, Herman PM, Marshall NJ, Qing Zeng, Anita Yuan, et al. (2019) Use of Complementary and Integrated Health: A Retrospective Analysis of U.S. Veterans with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain Nationally. J Altern Complement Med 25(1): 32-39.

- Wren AA, Ross AC, D Souza G, Christina Almgren 4, Amanda Feinstein, et al. (2019) Multidisciplinary Pain Management for Pediatric Patients with Acute and Chronic Pain: A Foundational Treatment Approach When Prescribing Opioids. Children (Basel) 6(2): 33.

- Zhang XC, Chen H, Xu WT, Song YY, Gu YH, et al. (2019) Acupuncture therapy for fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Pain Res 12: 527-542.

- Eccleston C, Fisher E, Thomas KH, Hearn L, Derry S, et al. (2017) Interventions for the reduction of prescribed opioid use in chronic non-cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11(11): CD010323.

- Bauer AB, Tilburt JC, Sood A, Li GX, Wang SH (2016) Complementary and Alternative Medicine Therapies for Chronic Pain. Chin J Integr Med 22 (6): 403-411.

- Shipton EA, Shipton EE, Shipton AJ (2018) A Review of the Opioid Epidemic: What Do We Do About It? Pain Ther 7(1): 23-36.

- Brass EP, Burnham RI, Reynolds KM (2019) Poison center exposures due to therapeutic misuse of nonprescription acetaminophen-containing combination products in the United States 2007-2016. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 57(5): 350-355.

-

MSN Gokgoz N, Pinar G. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Menopause Symptoms and Its Effect on Quality of Life Among Turkish Women. On J Complement & Alt Med. 5(3): 2020. OJCAM.MS.ID.000614.

-

CAM, Traditional Chinese medicine, Homeopathy, Naturopathy, Aspirin, Tylenol, Codeine, Opioid prescription, Complementary medicine alternative medicine

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.