Research Article

Research Article

A 10 Week Study to Determine the Effects of Live Vs Virtual Delivery of Transitions Program on Body Image

Terry Eckmann1, Heather Golly1*, Warren Gamas1, and Lesley Magnus2

1Department of Teacher Education and Kinesiology, Minot State University, USA

2Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Minot State University, USA

Terry Eckmann, Department of Teacher Education and Kinesiology 500 University Ave W, Minot State University Minot, ND 58707, United States.

Received Date:May 28, 2021; Published Date:July 08, 2021

Abstract

Home exercise regimens and digital streaming of exercise programs have become increasingly popular. The purpose of this study was to determine the impact of a 10 week delivery of in-person versus virtual delivery of the WELLBEATS™ Transitions group exercise class on body image. The study was conducted with sedentary women between the ages of 40 and 65 who volunteered for the study. The results indicated that a repeated measures GLM revealed a significant multivariate within group effect for participation in both exercise programs (pre-posttest), Wilks’ λ = .335, F (10, 30) = 5.96, p <. 001, partial eta squared = .665 indicating that participation in Transitions Live and Virtual fitness exercise programs impact participants’ perceptions on body image, body weight, eating issues, and physical appearance. Based on the findings in the current study either an in-person or virtual exercise program lasting 10 weeks can have a positive impact on body image in sedentary middle-aged women.

Keywords:Body Image; Exercise; Virtual

Abbreviations:MBSRQ: Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire

Introduction

The COVID pandemic has changed the face of the fitness industry in many ways, the closure of fitness centers meant the end of group exercise classes for over a year. Group exercise classes became a popular exercise option for adults over the past 40 years. Group exercise classes that were once scheduled at prime times in many fitness centers internationally were shut down. Providing group exercise classes to meet the scheduling needs of a diverse population was challenging for a variety of reasons; individuals with nontraditional schedules want to participate in a class at a time that is not popular enough to justify hiring a qualified fitness instructor, there can be difficulty in finding qualified fitness professionals, and there are instances in which fitness instructors are unable to teach a class due to illness or family issue and a substitute instructor is not available. The COVID pandemic halted group exercise classes altogether.

The American College of Sports Medicine’s 15th annual worldwide survey identified online training as number one and virtual training as number six top in top trends [1]. According to Thompson [2], “online training was developed for the at-home exercise experience” (p. 13). Online training uses digital data that is streamed through the internet to provide exercise programming that can be utilized for individuals or groups or for online exercise rehabilitation programs. The digital content can be watched live or prerecorded and downloaded for use. Thompson [2] describes that for the purpose of the Worldwide Survey of Fitness Trends for 2021 “virtual training was defined as the fusion of group exercise with technology” so workouts could be done when it worked for varied schedules (p.15). Virtual trainings are typically played on a large screen in fitness centers or other venues. They differ in that they are filmed rather than live.

Before, during and after the COVID pandemic, health and fitness providers seek cutting-edge ways to deliver group exercise classes for people to become more physically active. Research supports the many benefits of exercise on physical and mental health [3-5].

This research project is designed to explore the effects of the virtual training approach to group fitness on body image following WELLBEATS™ Live and Virtual Transition group exercise programming. To determine impact of WELLBEATS™ Live vs. Virtual Transitions on body image the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ), a self-report survey for the assessment of body image, was administered before and after the 10-Week Transitions intervention.

There were no studies found on the effects of virtual group exercise classes vs. live group exercise classes on body image. This research was designed to increase our understanding of how WELLBEATS™ Transitions live group instruction vs WELLBEATS™ Transitions virtual group exercise programs compare in regard to helping improve body image. The results will help health and fitness providers to make decisions about the viability of virtual group exercise programming and types of exercise to recommend to their clients. Along with adding to the scientific literature, the project provided directly benefit the participants. Participating in the study will give females age 45+ to 65 years of age who exercise sporadically or do not exercise the opportunity to improve their overall health and fitness.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Study Protocol

Sedentary female volunteers aged 45 to 65 years were selected to be in live or virtual groups for a 10 week time frame: WELLBEATS ™ Transitions live group or WELLBEATS™ Transitions virtual group. The researchers gained approval through the Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Research Subjects for study protocols. Volunteers were recruited through local television networks and social media announcements. Selected participants were required to provide a signed physician waiver indicating they were able to complete the requirements of the study protocol. The 10 week program required participants in the WELLBEATS™ Transitions live group and the WELLBEATS™ Transitions virtual group to participate two different formats of transitions classes three days a week. Subjects were considered untrained if they exercised sporadically (2 or 3 times a month, some months of the year) or had not participated in structured exercise over the past year which may have included yoga, flexibility, resistance or aerobic training. Prior to initiating the study and after the 10 week training program participants completed the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire. The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire was purchased and terms and conditions of use were followed [6].

Body Image Assessments: MBSRQ

The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ) is a self-report inventory for the assessment of body image which has been validated for the use with individuals 15 years of age and older [7]. The reliability of the MBSRQ subscales in females is high for initial testing, Cronbach’s alpha 0.73-0.90, and at a one-month retest, 0.74-.94 [7]. The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire as:

Body Image Assessments: MBSRQ

The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ) is a well-validated self-report inventory for the assessment of body image. Body image is conceived as one’s attitudinal dispositions toward the physical self. As attitudes, these dispositions include evaluative, cognitive, and behavioral components. Moreover, the physical self encompasses not only one’s physical appearance but also the body’s competence or “fitness” and its biological integrity or “health/illness.” The MBSRQ is intended for use with adults and adolescents (15 years or older) [5,6].

The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire subscales are described as:

MSBQR Subscales: Interpretations

Appearance Evaluation: Feelings of physical attractiveness or unattractiveness; satisfaction or dissatisfaction with one’s looks. High scorers feel mostly positive about their physical appearance; low scorers have a general unhappiness with their physical appearance.

Appearance Orientation: Extent of investment in one’s appearance. High scorers place more importance on how they look, pay attention to their appearance, and engage in extensive grooming behaviors. Low scorers are apathetic about their appearance; their looks are not especially important to them; they don’t spend much effort to “look good”.

Fitness Evaluation: Feelings of being physically fit or unfit. High scorers see themselves as fit and place high value on fitness. Low scorers do not value fitness.

Fitness Orientation: Extent of investment in being physically fit. High scorers value fitness and are physically active. Low scorers do not value physical fitness and don’t exercise.

Health Evaluation: Feelings of physical health or freedom from illness. High scorers feel in good health and low scorers feel unhealthy.

Health Orientation: Extent of investment in a physically healthy lifestyle. High scorers make healthy lifestyle choices and low scorers are apathetic about their health.

Illness Orientation: Extent of reactivity to being or becoming ill. High scorers feel in good health and low scorers feel unhealthy.

Body Area Satisfaction Scale: Similar to Appearance Evaluation except it taps satisfaction with discrete aspects of one’s appearance. High scorers indicate contentment with most areas of the body and low scorers are unhappy about size or appearance of several areas.

Overweight Preoccupation: This scale assesses a construct reflecting fat anxiety, weight vigilance, dieting, and eating restraint.

Self-Classified Weight: This scale reflects how one perceives and labels one’s own weight from underweight to overweight [5,7,8].

Results and Discussion

A repeated measures GLM revealed a significant multivariate within group effect for participation in both exercise programs (pre-posttest), Wilks’ λ = .335, F (10, 30) = 5.96, p <. 001, partial eta squared = .665 indicating that participation in Transitions Live and Virtual fitness exercise programs impact participants’ perceptions on body image, body weight, eating issues, and physical appearance. The type of exercise delivery of did not significantly change the perceptions on body image, body weight, eating issues, and physical appearance, Wilks’ λ = .805, F (10, 30) = 0.727, p = .693, partial eta squared = .195.

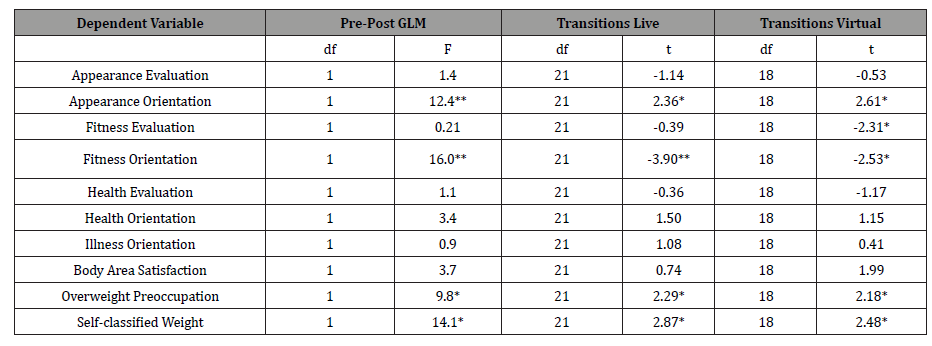

Table 1:

The results show that participation in Transitions Live and Transitions Virtual exercise programs made significant changes in Appearance Orientation, Fitness Orientation, Overweight Preoccupation, and Self- Classified Weight as measured by the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire. There were no significant differences in perceptions found between the two types of exercise deliveries.

Conclusion

This research indicates that Transitions Live and Transitions Virtual exercise can play a positive role in appearance orientation. Participants improved feelings of attractiveness and satisfaction with personal appearance. Participants in both groups also significantly improved fitness orientation, indicating an increase in their interest in investing time and effort to be more physically fit. Transitions live and virtual participants also improved their self-perception of being at a healthy weight as measured by the overweight and self- classified weight measures on the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire. These findings that individuals participating in either the Transitions Live or Transitions Virtual agree with the findings by Kohlstedt S, et al. [9], that studied self-efficacy, affect, and life satisfaction. These results suggest that participating in group exercise with a live or virtual instructor may have positive effects on body image.

McGuire A, et al. [10], performed survey research identifying barriers to exercise in middle- aged Australian women. The findings of their study indicated that this age group of women, which is similar to the current study, identify exercise self-efficacy, physical and mental well-being as barriers to exercise.

This lends to the importance of the findings in this study where participants who completed the exercise program had improvements in self-reported scores on appearance orientation, fitness orientation, overweight preoccupation, and self-classified weight regardless of the mode of exercise. Programming similar to either of those used in this study may help individuals to overcome these barriers to become regular exercisers. With steaming of fitness programming becoming popular during the social distancing era of the Covid pandemic the current research provides support for the efficacy of the digital format for improving body image and the factors associated with exercise self-efficacy [11].

Acknowledgement

No.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- American College of Sports Medicine (2021) The power of physical activity. Physical Activity: A prescription for health.

- Thompson, Walter R (2020) FACSM Worldwide Survey of Fitness Trends for 2021. ACSM's Health & Fitness Journal 25(1): 10-19.

- Blake H, Mo P, Malik S, Thomas S (2009) How effective are physical activity interventions for alleviating depressive symptoms in older people? A systematic Clin Rehabil 23(10): 873-887.

- Centers for Disease Control (2021) Benefits of physical Covid-19: How to be physically active while social distancing.

- Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS (2006) Health benefits of physical activity: the CMAJ 174(6): 801-809.

- Cash TF (2020) The multidimensional body-self relations questionnaire. MBSRQ Users’ Manual (3rd edn). Old Dominion University Press, VA, USA.

- Cash TF (2012) Body Image Research Consulting.

- Brown TA, Cash TF, Mikulka PJ (1990) Attitudinal body image assessment: factor analysis of the Body-Self Relations Questionnaire. J Pers Assess 55(1-2): 135-144.

- Kohlstedt S, Weissbrod C, Colangelo A, Carter M (2013) Psychological Factors influencing Exercise Adherence among Psychology 4(12): 917-923.

- McGuire A, Seib C, Anderson D (2016) Factors predicting barriers to exercise in midlife Australian Women. Maturitas 87: 61-66.

- Schmitz K, Campbell A, Stuiver M, Pinto B, Schwartz A, et al. (2019) Exercise is medicine in oncology: Engaging clinicians to help patients move through CA Cancer J Clin 69(6): 468-484.

-

Craig Triplett, Michelle Triplett, Nathan Deichert, Molly Graesser, Corey Selland, Ashley Pfeiffer, Dan Jensen. The Effects of Strengthening the Lumbar Multifidus and Transverse Abdominis in Healthy Individuals Using an Augmented Feedback System: A Randomized Control Trial. On J Complement & Alt Med. 6(4): 2021. OJCAM.MS.ID.000644.

-

Body Image; Exercise; Virtual; Virtual Delivery; Transitions Program; Body Image; Exercise regimens; Exercise programs; Virtual fitness; Physical appearance; Fitness instructors; Family issue; Illness; Virtual training

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.