Research Article

Research Article

Mortality Risk and Intensive Care Unit Treatment in Patients with Down Syndrome and Intellectual Disability Hospitalized with COVID-19

Verena Hofmann1* and Dagmar Orthmann Bless2

1Department of special education, University of Fribourg, Switzerland

2Department of special education, University of Fribourg, Switzerland

Verena Hofmann, Department of special education, University of Fribourg, Switzerland Rue St-Pierre-Canisius 21, CH-1700 Fribourg, FR, Switzerland

Received Date:July 14, 2025; Published Date:July 24, 2025

Abstract

People with Down syndrome and other forms of intellectual disability are particularly at risk for severe COVID-19 progression, due to their high prevalence of comorbidities and genetic predispositions. Using medical statistics of Swiss hospitals (2020-2022), we investigated whether the risk of mortality and ICU admission for people with Down syndrome and people with intellectual disabilities differed by year of hospital admission, and whether it differed from older patients and patients without identified risks. Results indicate a higher mortality risk in patients with intellectual disabilities and older patients at the beginning of the pandemic. A similar effect was found regarding ICU admission in patients with Down syndrome. These effects were no longer significant when older patients were excluded from the disability groups. Since more conservative analyses did not find any decreased risk over the course of the pandemic, this raises the question of better protective measures for people with disabilities.

Keywords:Intellectual Disability; Down Syndrome; COVID-19; Mortality; Intensive Care Unit Treatment

Introduction

Individuals with intellectual disabilities were particularly impacted by COVID-19 with regard to increased risk of infection, barriers in accessing and understanding information, and risk of developing mental health problems [1,2]. This study investigated the physical vulnerabilities related to COVID-19 of people with Down syndrome and people with an intellectual disability. The analyses were based on medical statistics from hospital admissions of individuals diagnosed with COVID-19 in Switzerland between 2020 and 2022. The two groups with disability were compared to older patients, who also represent a risk group (for an overview see, [3], and to patients under age 65 and without an intellectual disability. People with Down syndrome are assumed to be particularly at risk for COVID-19, due to their high prevalence of medical complications and genetic predispositions that are thought to be related to an increased risk of severe disease progression [4,5,8]. Hence, during the pandemic, the Swiss government assigned people with Down syndrome a special status as a separate risk group. Some of these comorbidities also apply to people with intellectual disabilities not further specified [9,10]. This population was not listed as a special risk group but may have had this status indirectly if they suffered from one of the pre-existing conditions relevant to COVID-19. However, people with intellectual disabilities represent a very heterogeneous group, which is difficult to clearly categorize. Improved insights into the vulnerability of people with intellectual disabilities as well as those with specific syndromes could allow health protections to be adapted more precisely to the needs of these people in future pandemics. An earlier study by the authors (Hofmann & Orthmann Bless, 2024), which examined combined data from 2020 and 2021 (not a longitudinal assessment), found evidence of increased likelihood of infection and more severe disease progression, especially a higher risk of mortality, in people with Down syndrome compared to hospitalized individuals without Down syndrome. In order to expand on these results, a second group of patients with intellectual disabilities (but without Down syndrome) was included in the current study, and potential change over three years of the pandemic was investigated. Change over time was compared to patients without intellectual disabilities.

Risk Factors Among People with Intellectual Disabilities

People with Down syndrome are more likely to have comorbidities that are risk factors for severe disease progression of COVID-19 [5-8], including obesity, cardiac and respiratory disease, and diabetes. Additional risk factors are increased prevalence of immune dysregulation caused by Trisomy 21 and other genetic specificities that facilitate infection with SARS-CoV-2 [4,6,11,12]. International studies have confirmed this increased risk: A recent systematic review, which included 55 articles from 24 countries, found that people with Down syndrome are more susceptible to COVID-19 infections and severe disease progression due to comorbidities, immunological factors, and residential situation [13]. Further, studies have found that people with Down syndrome are more likely to require intensive care unit (ICU) treatment and to receive invasive mechanical ventilation after a COVID-19 infection [14,15,16]. These findings might be due to the fact that people with Down syndrome are more susceptible to pulmonary diseases, including pneumonia [17,18]. In addition, there is evidence that sepsis resulting from COVID-19 infection is more common in people with Down syndrome compared to people without Down syndrome [16]. Abnormal inflammatory responses have also been observed in Down syndrome, suggesting that the course of the disease may differ from that of the general population [19]. Furthermore, individuals with Down syndrome are at significantly increased risk of mortality following hospitalization with COVID-19, an increase that varies from approximately two to ten times [14,15,20,21]. People with Down syndrome who died from COVID-19 were younger and had a higher incidence of superinfections, autoimmune disease, obesity, and dementia, compared to people without Down syndrome [22]. However, a large variation was also found within the population with Down syndrome. This variation was particularly due to age differences: people with Down syndrome and higher age were at significantly higher risk of mortality than younger people with Down syndrome [23].

While studies among individuals with Down syndrome almost consistently indicate an increased risk of severe disease progression, the situation is far more complex in intellectual disabilities of other etiologies. Comorbidities associated with increased risk of severe outcomes related to COVID-19 infection can also be assumed in this population, although people with intellectual disabilities are not at higher risk regarding all potential risk factors. A large-scale study from the UK investigated the prevalence of a variety of physical and mental conditions in people with intellectual disabilities compared to those without intellectual disability [24]. As with people with Down syndrome, a larger proportion of individuals with an intellectual disability was found to be overweight compared to people without intellectual disabilities. Gastrointestinal conditions were more common as well. In contrast to people with Down syndrome, cardiovascular diseases and non-type 1 diabetes were not more prevalent in people with intellectual disabilities compared to the typical population. There were, however, slightly higher rates of type 1 diabetes. Apart from physical comorbidities, the social context in which people with Down syndrome and people with intellectual disabilities live also matters. For example, it is more difficult for people with lower intellectual functioning to understand and comply with protective measures such as mask wearing and physical distancing [25] making them more reliant on the support of caregivers. On the other hand, persons with more severe intellectual disability who lived in social medical institutions, were subject to more stringent protective measures than private households during the pandemic [26] which might have reduced their risk of infection. Furthermore, social differences between people with Down syndrome and people with other forms of intellectual disability are likely, although these have rarely been investigated. These include, for example, the overrepresentation of people with intellectual disabilities in lower social classes [27,28] whereby lower social class is associated with a host of risks; in contrast, Down syndrome occurs independent of social class. However, since this dataset cannot provide information on this variable, the present paper focuses on physical vulnerability.

COVID-19 Policies in Switzerland and Change Over the Years

In the context of a pandemic, both national health protection policies and the quality and characteristics of the health care system (e.g., financial, spatial, and staff resources; knowledge; priorities; treatment approaches; the availability of prevention and treatment measures) must be considered. Therefore, we first provide basic information on Swiss health policy regarding COVID-19 as context for our study Switzerland uses a federal system, whereby the federal government and cantons (i.e., districts) share responsibility for population health. Shared responsibility also exists for pandemic management. However, in the case of a special emergency situation (Art. 6 of the Epidemic Law, EpG SR 818.101), the federal government can order measures that must be implemented in all cantons.

In September 2020, the federal government created a COVID-19 Law and a COVID -19 Ordinance Special Situation (SR 818.101.26). Federal COVID-19 policy was guided by the principles of subsidiarity, effectiveness, and proportionality. Uniform federal regulations were established with respect to vaccination, testing, and recovery records. Categories of persons at particular risk were defined by the [26] Federal Office of Public Health (2021). Persons with Down syndrome age 16 and older were one of four specially designated risk groups, along with persons age 65 and older, persons with chronic diseases age 16 and older, and pregnant women. People with intellectual disabilities were not automatically defined as a risk group but could belong to a risk group if they had any of the listed diseases. Designation as a special risk group had several implications, including prioritization for vaccines. Vaccinations were strongly recommended but not mandatory for any population group. In addition, the federal government recommended and temporarily mandated special measures for social medical institutions (including institutions for persons with disabilities). These measures included, for example, visitation and contact restrictions, strict hygiene rules, and isolation measures in case of infection. As in other countries, COVID-19 measures in Switzerland changed over the course of the pandemic. Although restrictions tended to be milder than in other countries, there were periods of stricter measures from spring 2020 onwards, including the closure of stores and a near shutdown of public life (albeit without a curfew), which alternated with periods of reopening. By 2021, complete shutdowns ceased to be mandated, although far-reaching measures were still in place, such as the closure of restaurants. The vaccination campaign began in spring 2021 and prioritized vaccinating risk groups, which was subsequently accompanied by a gradual reduction in restrictions. From summer 2021, it was primarily major events that continued to be constrained. In 2022, no COVID-19 measures were in effect in Switzerland, except for specific recommendations such as follow-up vaccinations (especially for people at risk), wearing masks in certain situations, and isolating if experiencing COVID-19 symptoms. It can be assumed that the change in restrictions, the vaccination campaign, and the way people responded to the pandemic impacted which groups were hospitalized with COVID-19, how their disease progressed, and the mortality rate in specific populations. For example, a recent study demonstrated that vaccination had a significant protective effect against mortality in people with Down syndrome [29]. Given that people with Down syndrome were considered a risk group in Switzerland and thus given priority in the vaccination campaign, these factors could have contributed to a reduction in the risk of severe disease progression that would be noted in the data beginning in 2021, or 2022 at the latest. It is unclear to what extent this trend can also be expected for people with intellectual disabilities without Down syndrome, as they only indirectly belonged to the prioritized groups in cases of pre-existing conditions or old age.

Objectives of The Current Study

The purpose of this study was to investigate risk of mortality and ICU treatment among patients with Down syndrome and patients with other forms of intellectual disability, to understand how this risk changed over the years 2020, 2021, and 2022. We used data from the Medical Statistics of Swiss Hospitals. We further sought to compare mortality risk and ICU treatment between patients with Down syndrome, patients with other forms of intellectual disability, older patients, who have been considered a high-risk group throughout the pandemic [3], and patients without one of these risk factors (i.e., under age 65, no genetic syndrome, and no intellectual disability). It was not possible to exclude other potential risk factors in the latter group, because not all pre-existing conditions are registered on hospital admission.

We examined the following research questions:

(1) What is the frequency of mortality for both the 3-year

period (2020, 2021, 2022) and for each year, among patients

with Down syndrome and patients with other forms of

intellectual disability who are diagnosed with COVID-19?

(2) Does year of admission predict risk of mortality, and

are there differences between patients with Down syndrome,

patients with other forms of intellectual disability, older

patients, and patients with none of these risk factors (i.e., under

age 65)?

(3) What is the frequency of ICU treatment for both the 3-year

period and for each year, among patients with Down syndrome

and patients with other forms of intellectual disability who are

diagnosed with COVID-19?

(4) Does year of admission predict ICU treatment, and are

there differences between patients with Down syndrome,

patients with other forms of intellectual disability, older

patients, and patients with none of these risk factors (i.e., under

age 65)?

Materials and Methods

Medical Statistics of Swiss Hospitals

Data from the Medical Statistics of Swiss Hospitals consist of mandatory reports documenting all treatment cases dating back to 1998. A treatment case is defined as an inpatient hospital stay from entry until exit. Thus, the statistics always refer to a stay and not to a person. If a person is repeatedly admitted to the hospital, then a new entry is made upon each admission. Reported statistics include demographic data (e.g., age, sex, nationality) and information on hospital stay (e.g., type of admission, length of stay). All diagnoses are coded according to the International Statistical Classification Of Diseases And Related Health Problems, 10th revision, German Modification (ICD-10-GM, 2012). All treatments are coded according to the Swiss Operation Classification [30] (Federal Statistical Office, 2021). We entered in a data usage agreement for three years of data (2020 - 2022) with the Swiss federal government, as represented by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office. Some data was removed or further encrypted to protect data privacy (e.g., date of birth).

Data Preparation and Sampling Procedure

The initial data set consisted of all hospital admissions in 2020, 2021, and 2022 where a COVID-19 diagnosis (ICD-10 code of U07.1! COVID-19, virus detected; N = 147,959) was recorded. Of these, the cases that involved a person with Down syndrome (ICD- 10 code of Q90.0 – Q90.9) or another form of intellectual disability (ICD-10 code of F70 – F79: mental retardation) were identified. A total of 180 admissions of people with Down syndrome and 539 people with an intellectual disability were found. Based on the larger group (N = 539), a random sample of cases without chromosomal abnormality and without intellectual disability was drawn. Proportional stratification by year was applied, as the number of admissions with a COVID-19 diagnosis varied by year (2020: N = 35,993; 2021: N = 39,696; 2022: N = 71,551). The final sample comprised 540 cases.

Data Analyses

We first examined the demographic data of the final sample. The frequencies of mortality and ICU treatment among patients with Down syndrome and patients with other forms of intellectual disability were analyzed descriptively, in total and by year (2020, 2021, and 2022). Descriptive comparisons with older patients and younger patients without intellectual disabilities were conducted as well. Logistic regression analyses were then used to examine whether year of admission significantly predicted the relative probability of mortality and ICU treatment for each group and whether these effects differ between people with Down syndrome, other forms of intellectual disability, age 65 and older, and without any of these risk factors.

We further conducted sensitivity analyses to test whether the effects remain stable when older age is excluded in the two disability groups. This excluded 9 people with Down syndrome who were age 65 and older, and reduced the sample from 180 to 171. Among the patients with other forms of intellectual disability, however, there were 187 people age 65 and older, thus this sample was reduced from 539 to 352.

Results and Discussion

Sample Demographics

The following demographics refer to the total sample of people with Down syndrome and other forms of intellectual disability, as well as the random sample of people without Down syndrome, who were hospitalized between January 1, 2020 and December 31, 2022 and had a COVID-19 diagnosis (N = 1,259). Demographic data was determined by the way in which they were recorded in the Medical Statistics of Swiss Hospitals. Age was coded categorically using 20 levels (each covering five years). The lowest age category consisted of patients age 0 - 4 years and the highest category was 95 years and older. Gender was assessed using a binary variable (male, female).

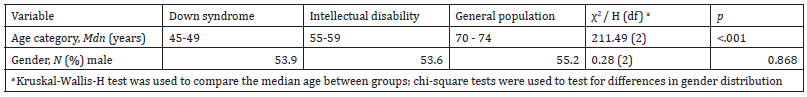

As can be seen in Table 1, the median age category of patients with Down syndrome who were hospitalized (45 - 49 years) was lower than that of patients with other forms of intellectual disability (55 - 59 years) and the hospital population without intellectual disability (70 – 74 years). These differences were significant (p < .001). In contrast, the gender distribution was homogeneous between groups (p = .868) with slightly more men in all groups (from 53.6 to 55.2 %) (Table 1).

Table 1:Sample Demographics (N = 1,259).

Main Results

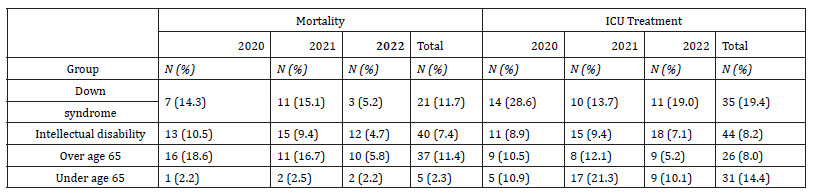

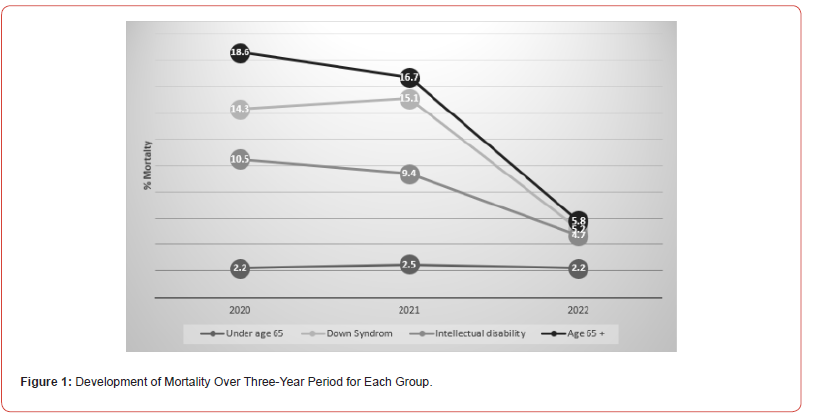

As can be seen in Table 2, 21 patients with Down syndrome (11.7 %) who had a COVID-19 diagnosis died between 2020 and 2022. On a descriptive level, there was a small increase from 2020 (14.3 %) to 2021 (15.1 %) and a greater decrease from 2021 to 2022 (5.2 %; see also Figure 1). Among people with intellectual disabilities without Down syndrome, 12 patients (4.7%) died. Again, the highest percentage was in 2021 (9.4%), but with a less pronounced decrease in 2022 (4.7 %) than for Down syndrome. In the random sample without Down syndrome or intellectual disability, there has been a continuous decrease in the percentage among people age 65 and older (declining from 18.6 % in 2020 to 5.8 % in 2022) as well as a consistently low level among people under 65 (between 2.2 % and 2.5 %, with the highest percentage in 2021) (Table 2) (Figure 1).

Table 2:Mortality and ICU Treatment Frequencies for all Groups Over the Three-Year Period.

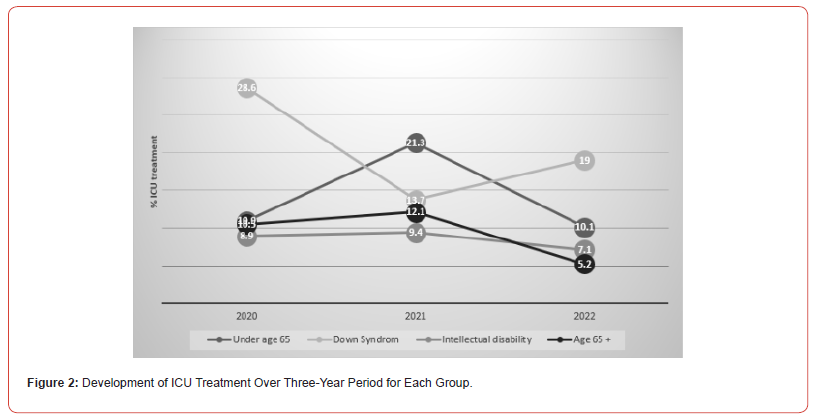

In total, 35 (19.4%) patients with Down syndrome received ICU treatment, as did 44 (8.2%) patients with intellectual disabilities. People with Down syndrome were most frequently treated in the ICU in 2020, with the frequency dropping in 2021 (13.7%) before rising in 2022 (19.0%; see also Figure 2). The proportion of people with intellectual disabilities was 9.4 % in 2021, and this rate was only slightly lower in 2020 (8.9 %) and in 2022 (7.1 %). For patients age 65 and older, the highest rate of ICU treatment was likewise recorded in 2021 (12.1%), and for patients under 65 this rate peaked in 2020 (21.3 %) (Figure 2).

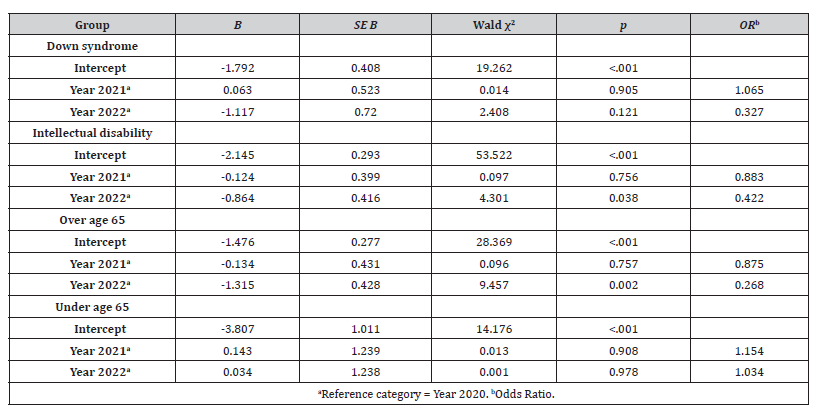

Logistic regression analyses were used to examine whether year of hospital admission predicted relative risk of mortality (see Table 3). For patients with Down syndrome, there were no significant differences between the years, thus it can be assumed that probability of mortality is not dependent on year of hospitalization, despite the descriptive differences mentioned above. However, people with intellectual disabilities experienced a significant difference between 2020 and 2022 (p = .038), which indicates that their relative risk for mortality was 57.8 % lower in 2022 (OR = .422). The same difference was found for people age 65 and older, but even more pronounced with a decrease in risk of 73.2 % from 2020 to 2022 (p = .002, OR = .268). In line with the descriptive stability of low levels of mortality in the group under 65 years (and without intellectual disability), there were no significant differences between the years in this group (Table 3).

Table 3:Logistic Regression Analysis to Predict Mortality by Year for Each Group.

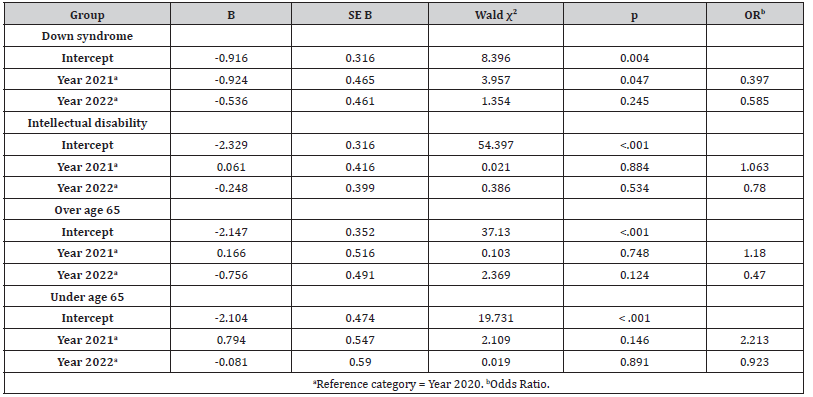

The same procedure was used to examine whether probability of ICU treatment depended on year of admission (see Table 4). People with Down syndrome were treated significantly less frequently in the ICU in 2021 than in 2020 (i.e., the probability was reduced by 60.3 %; p = .047, OR = .397). However, no significant differences were observed in patients with intellectual disabilities or in older and younger patients without intellectual disabilities. To conduct additional sensitivity analyses, all persons age 65 and older were excluded from the groups of patients with Down syndrome and intellectual disability, in order to make the groups even more distinctive and to avoid potential confounding effects of age. After doing so, the non-significant effects remained; However, the observed decrease in mortality risk in 2022 compared to 2020 disappeared once older people were excluded from the sample (B = -1.071, SE = 0.723, Wald (1) = 2.197, p = .138, OR = .343). The same occurred for the significantly lower ICU treatment for people with Down syndrome in 2021 compared to 2020: Here, the exclusion of persons age 65 and older meant that the boundary to significance was narrowly missed (B = -0.904, SE = 0.466, Wald (1) = 3.761, p = .052, OR = .405) (Table 4).

Table 4:Logistic Regression Analysis to Predict ICU Treatment by Year for Each Group.

Discussion of Results

As expected, the mortality rate of the three risk groups (Down syndrome, intellectual disability, older age) was elevated compared to that of the group without identified risk. This was evident both overall and within individual years. Although descriptive statistics found a downward trend in mortality for all three risk groups over the three-year period, the inferential statistical results revealed no significant differences in risk of mortality among people with Down syndrome by year of hospital admission. The same was true for people without identified risk factors, whose risk of mortality was constantly low. However, among patients with intellectual disabilities as well as those age 65 and older, a decreased risk of mortality from year 2020 to 2022 was observed. This could be a first indication that both people with intellectual disabilities and older adults might have been at higher risk at the beginning of the pandemic, and that this risk decreased with better treatment options, the availability of vaccines, and increasing immunization rates in the community. Yet, when older people were excluded from the analyses, year of admission no longer predicted mortality risk among patients with intellectual disabilities. This could mean that older age is the most decisive factor affecting mortality risk for people with intellectual disabilities, above and beyond the relevance of other vulnerabilities associated with intellectual disabilities. This finding makes sense given that older age was always considered one of the most important risk factors for severe COVID-19 progression [3]. It can therefore be assumed that among people with intellectual disabilities, older people were likewise most at risk.

When considering ICU treatment frequencies, the pattern differed from that for mortality. Since treatment in the ICU is an indicator of severe disease progression, yet also represents the chance of recovery, the proportion of people without identified risk was even higher at times. In addition, no continuous decrease was observed over the study period for people with Down syndrome and those without an identified risk. For example, the highest rate of ICU treatment among people without an identified risk was observed in 2021, whereas the opposite was true for people with Down syndrome, whose highest percentage occurred in 2020. The only statistically relevant effect was for people with Down syndrome in 2020 compared to 2021, whereas ICU treatment frequency did not differ significantly over the years among all other groups. Thus, it appears that patients with Down syndrome were particularly susceptible to severe disease progression at the beginning of the pandemic, to the point of requiring treatment in the ICU. This finding corresponds with studies on the increased vulnerability of patients with Down syndrome due to comorbidities, which became less critical as the pandemic continued. However, it remains unclear why this effect was not also seen in mortality and why the largest decrease in ICU treatment occurred in 2021 and not in 2022, when vaccination and general immunization had progressed even further. Of note, the effect in patients with Down syndrome was no longer statistically significant when people aged 65 and older were excluded from the analyses. As with mortality risk in people with intellectual disabilities, age may have a stronger influence than other aspects related to Down syndrome. This result is consistent with studies that have found a higher risk with increasing age in the Down syndrome population [23], although the study findings related to mortality and not to ICU treatment.

Year of admission was not a reliable predictor of mortality and ICU treatment and there was no clear pattern that suggested year of admission affected people with Down syndrome and people with intellectual disabilities compared to patients without such a diagnosis. An earlier paper by the authors (Hofmann & Orthmann Bless, 2024) found evidence for a generally increased risk of severe disease progression in Down syndrome, especially a higher risk of mortality. Yet, the current results indicate that the risk for people with Down syndrome or intellectual disability was not more strongly dependent on the course of the pandemic, treatment options, and immunization than was the case for the general hospital population. One explanation for this finding may be that older age appears to have a stronger explanatory effect than disability. In addition, the relatively small group sizes, especially in patients with Down syndrome, may have impacted on our study’s power to detect significant effects.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Overall, there was a tendency toward lower risk in the later years of the study period, although profiles between groups were more heterogeneous for ICU admission. This decreased risk is not surprising, as it coincided with more efficient measures against severe disease progression (e.g., new medications and vaccines) and increased community immunity. However, given that the statistical significance of our results disappeared when more conservative analyses were conducted, the decrease should not be overestimated. We could argue that there should have been a stronger decrease over time in risk for vulnerable groups, such as people with disabilities, since they were especially protected and prioritized in the vaccination campaign. On the other hand, risk status does not disappear even with high levels of protection and medical interventions. Earlier analyses by the authors (Hofmann & Orthmann Bless, 2024) found that general risk of mortality among patients with Down syndrome in the first two years of the pandemic was highly elevated compared to patients without Down syndrome, a result that was comparable to findings from other countries. It could therefore be assumed that increased mortality and an increased risk of complications in the risk groups cannot be completely eliminated with protections and medical prioritization. At the same time, the importance of providing vulnerable groups with special protections should be emphasized, as the situation would otherwise presumably be far less favorable.

Since the present study also has limitations, there are perspectives that should be addressed in future research projects. The current data, which was based on national mandatory statistics collected from all Swiss hospitals over three years, allowed us to investigate the entire population of people with Down syndrome who were admitted to a Swiss hospital during a three-year span of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, with regard to people with intellectual disabilities (without Down syndrome), not all those hospitalized with COVID-19 may have been identified and coded as having an intellectual disability. Although the ICD-10 includes codes for mild, moderate, and severe intellectual disability (without further details), it is still possible that in cases of severe disease, a mild disability was not recognized and therefore might not have been coded. This possibility is less likely in Down syndrome due to the syndrome’s clearly visible characteristics. It can therefore be assumed that unrecognized intellectual disability might be present in the data. Further, it was not possible to link data from the Medical Statistics of Swiss Hospitals with statistics on patient cause of death, thus it is unclear whether a person died with or from COVID-19. Studies that can provide more precise information about the cause of death or severe disease progression among people with Down syndrome or intellectual disability would help fill this research gap. One methodological limitation is the relatively small sample size of persons with disabilities, especially those with Down syndrome. Although all available data was used and reliable coding in the medical statistics is assumed, the total number of hospital admissions for people with Down syndrome was low, and the number of patients who died or received ICU treatment was even lower. This small sample size decreased the power of our analyses and could have contributed to the lack of significant findings. Replicating these results with a larger sample of patients with Down syndrome could be beneficial.

Funding

The study was funded by the Department of Special Education of the University of Fribourg, Switzerland, and by the Curative Education Center Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

- Bakaniene I, Dominiak-Świgoń M, Meneses da Silva Santos MA, Pantazatos D, et al. (2023) Challenges of online learning for children with special educational needs and disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 48(2): 105-116.

- Courtenay K, Perera B (2020) COVID-19 and people with intellectual disability: Impacts of a pandemic. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine 37(3): 231-236.

- Levin AT, Hanage WP, Owusu-Boaitey N, Cochran KB, Walsh SP, et al. (2020) Assessing the age specificity of infection fatality rates for COVID-19: systematic review, meta-analysis, and public policy implications. European Journal of Epidemiology 35(12):1123-1138.

- Bensussen A, Valcarcel A, Álvarez-Buylla ER, Díaz J (2022) ORF8 and health complications of COVID-19 in Down syndrome patients. Frontiers in Genetics 13:1-4.

- Bakaniene I, Dominiak-Świgoń M, Meneses da Silva Santos MA, Pantazatos D, Grammatikou M, et al. (2023) Challenges of online learning for children with special educational needs and disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 48(2): 105-116.

- Capone GT, Chicoine B, Bulova P, Stephens M, Hart S, et al. (2018) Co-occurring medical conditions in adults with Down syndrome: A systematic review toward the development of health care guidelines. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 176(1):116-133.

- Espinosa JM (2020) Down syndrome and COVID-19: A perfect storm? Cell Reports Medicine 1(2): 1-8.

- Illouz T, Biragyn A, Frenkel-Morgenstern M, Weissberg O, Gorohovski A, et al. (2021) Specific susceptibility to COVID-19 in adults with Down syndrome. NeuroMolecular Medicine 23(4): 561-571.

- Hofmann V, Orthmann Bless D (2024) COVID-19 in patients with Down syndrome: Characteristics of hospitalisation and disease progression compared to patients without Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 49(3): 353-361.

- Nankervis K, Chan J (2021) Applying the CRPD to People With Intellectual and Developmental Disability With Behaviors of Concern During COVID-19. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 18(3): 197-202.

- Perera B, Laugharne R, Henley W, Zabel A, Lamb K, et al. (2020) COVID-19 deaths in people with intellectual disability in the UK and Ireland: descriptive study. BJPsych Open 6(6): 1-6.

- Evangelho VGO, Bello ML, Castro HC, Amorim MR (2022) Down syndrome: The aggravation of COVID-19 may be partially justified by the expression of TMPRSS2. In Neurological Sciences 43:789-790.

- Majithia M, Ribeiro SP (2022) COVID-19 and Down syndrome: The spark in the fuel. In Nature Reviews Immunology 22(7): 404-405.

- da Silva MVG, Pereira LRG, de Avó LR da S, Germano CMR, Melo DG (2024) Enhancing understanding of SARS-CoV-2 infection among individuals with Down syndrome: An integrative review. Sao Paulo Medical Journal, 142(2): 1-10.

- Boschiero MN, Lutti Filho JR, Ortega MM, Marson FAL, et al. (2022) High case fatality rate in individuals with Down syndrome and COVID-19 in Brazil: A two-year report. Journal of Clinical Pathology 75(10): 717-720.

- Emami A, Javanmardi F, Akbari A, Asadi-Pooya AA, et al. (2021) COVID-19 in patients with Down syndrome. Neurological Sciences 42(5): 1649-1652.

- Malle L, Gao C, Hur C, Truong HQ, Bouvier NM, et al. (2021) Individuals with Down syndrome hospitalized with COVID-19 have more severe disease. Genetics in Medicine 23(3): 576-580.

- Aparicio P, Barba R, Moldenhauer F, Suárez C, Real de Asúa D (2023) What brings adults with Down syndrome to the hospital? A retrospective review of a Spanish cohort between 1997 and 2014. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 36(1): 143-152.

- Chicoine B, Rivelli A, Fitzpatrick V, Chicoine L, Jia G, et al. (2021) Prevalence of common disease conditions in a large cohort of individuals with Down syndrome in the United States. Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews 8(2): 86-97.

- Granholm ACE, Englund E, Gilmore A, Head E, Yong WH, et al. (2024) Neuropathological findings in Down syndrome, Alzheimer’s disease and control patients with and without SARS-COV-2: preliminary findings. Acta Neuropathologica 147(1): 1-21.

- Boschiero MN, Palamim CVC, Ortega MM, Marson FAL (2022) Clinical characteristics and comorbidities of COVID-19 in unvaccinated patients with Down syndrome: First year report in Brazil. Human Genetics, 141(12):1887-1904.

- Clift AK, Coupland CAC, Keogh RH, Hemingway H, Hippisley-Cox J (2021) COVID-19 mortality risk in Down syndrome: Results from a cohort study of 8 million adults. Annals of Internal Medicine174: 572-576.

- Villani ER, Carfì A, Di Paola A, Palmieri L, Donfrancesco C, et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of individuals with Down syndrome deceased with CoVID-19 in Italy-A case series. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part A 182(12): 2964-2970.

- Pitchan Velammal PNK, Balasubramanian S, Ayoobkhan FS, Mohan GVK, Aggarwal P, et al. (2024) COVID-19 in patients with Down syndrome: A systematic review. Immunity, Inflammation and Disease 12(3): 1-8.

- Perera B, Audi S, Solomou S, Courtenay K, Ramsay H, et al. (2020) Mental and physical health conditions in people with intellectual disabilities: Comparing local and national data. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 48: 19-27.

- Fujino H, Itai M (2023) Disinfection behavior for COVID-19 in individuals with Down syndrome and caregivers’ distress in Japan: A cross-sectional retrospective study. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 35(1): 81-96.

- Federal Office of Public Health (2021) COVID-19: Informationen und Empfehlungen für sozialmedizinische Institutionen wie Alters- und Pflegeheime.

- Neuhäuser G, & Steinhausen HC (2013) Geistige Behinderung: Grundlagen, Erscheinungsformen und klinische Probleme, Behandlung, Rehabilitation und rechtliche Aspekte. Kohlhammer.

- Nussbeck S (Ed.), Biermann A, (Ed.), AdamH (Ed.). (2008) Sonderpädagogik der geistigen Entwicklung. Hogrefe.

- Sánchez Moreno B, Adán-Lirola L, Rubio-Serrano J, Real de Asúa D (2024) Causes of mortality among adults with Down syndrome before and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 68(2): 128-139.

- Federal Statistical Office (2021) Swiss classification of surgical interventions (CHOP): Systematic index-version 2021.