Research Article

Research Article

Specific Factors Influencing Child Custody Evaluations

Alexandra Massimillo Webster*, Stephen E Berger and Laird Bridgman

The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, USA.

Alexandra Massimillo Webster M.A, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, USA.

Received Date: May 03, 2022; Published Date: June 03, 2022

Abstract

Child custody evaluations are often ordered by a judge when there is a disagreement between parents on what is in the best interest of their children. Psychologists are often the mental health professionals who get appointed to conduct these evaluations, and as such, there is an expectation that these assessments are made in an objective manner, free from the interference of explicit or implicit bias. While the importance of child custody decisions and the presence of biases have been studied separately in the literature, research has largely ignored how biases may play a role in child custody evaluations. Specifically, the literature has yet to investigate whether or not psychologists who conduct child custody evaluations are influenced by their own unconscious biases regarding race and gender. Thus, the current study sought to quantitatively assess for bias of licensed psychologists who do conduct child custody evaluations and licensed psychologists who do not conduct child custody evaluations. Results suggest there were few differences between the two groups. Additionally, the fact that so few differences between these two groups were found may indicate that the basic training and education that all clinical psychologists are exposed to during their doctoral programs and their continuing education are clearly fundamental to the profession.

Keywords: Child Custody: Bias; Evaluations; Parent qualities

Introduction

A divorce is a significant life event whose possible negative impact may be exacerbated by the need to have child custody decisions decided by a court. After a divorce, approximately 6 to 20% of child custody disputes are decided by the court [1]. Within this percentage of child custody disputes handled by the courts, approximately 10% are determined to have the need for a child custody evaluation [2].

The most common referral reasons for a child custody evaluation include those cases in which one parent is alleged to have a mental disorder or mental instability, when there are allegations of abuse or neglect, when there is parental conflict, and when there are allegations of alcohol or substance abuse [3].When judges and attorneys were surveyed regarding the top reasons a child custody evaluation may be implemented, both groups agreed that cases of mental instability or the presence of a mental disorder on the part of one or both parents, and allegations of abuse or neglect were the most common referral reasons [3]. While these are shown to be the most common reasons for the need for a child custody evaluation, they are not the only reasons. There are many other reasons the court may request a child custody evaluation, ranging from geographic distance between the parents, to facilitating a child’s relationship with the other parent to impaired parenting skills [3].

When child custody is disputed, and there is, based on the situation, a need for a referral for a child custody evaluation, the court will rely on a mental health professional to conduct the evaluation. These professionals may include psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers [4]. While these professionals may vary on their training and expertise regarding child custody evaluations, the legal profession expects those conducting child custody evaluations to be objective and unbiased in their work [5]. While child custody decisions have significant and long-lasting effects on children (and the family system at large), the actual influence of a child custody evaluation on the judge’s final ruling is unknown, as it has not been assessed in the literature [4]. However, judges are more likely to take into consideration the report of an evaluator if they presume that the evaluator has conducted their assessment in a scientific and objective manner [3,4]. A significant legal consideration regarding expert testimony is whether the expert should render an opinion on what the outcome should be, which is called: the ultimate issue. In other words, the ultimate outcome/decision technically is in the hands of the judge, but what role should the expert play in offering an opinion on the “ultimate issue” has been a hotly debated issue in the legal arena. For example, after the John Hinkley trial (attempted assassination of President Reagan), U.S. federal law was changed so that experts could no longer express an opinion on the “ultimate issue” of whether a defendant was legally insane at the time of an attempted crime. Additionally, in regard to child custody evaluations, while it is debated whether evaluators should or do address the ultimate issue (i.e., recommending which parent should receive custody), Bow and Quinnell found that approximately 94% of psychologists included in the sample stated that they do address the ultimate issue for the court [3].

For these reasons, the importance of a child custody evaluation can be substantial as it can be used to inform the judge’s decision regarding custody and time allocation with each parent. Especially with younger children, recommending a child be with one parent over the other may affect the child’s ability to form healthy attachment(s) to either or both parents. Custody decisions, in general, can have a negative impact on the entire family system [6,7]. Because of this, it is crucial to understand how child custody evaluator’s own implicit, unconscious biases may be impacting their ability to make an objective decision.

Psychologists are, at the end of the day, inherently human, and therefore no more or no less potentially susceptible to bias than any other individual in the world. However, psychologists have an ethical duty to be aware of these biases, according to the Ethics Code of the American Psychological Association’s (APA). In 1994, the APA introduced Guidelines for Child Custody Evaluations in Family Law Proceedings that aspired psychologists who perform child custody evaluations to embody specific and extensive competency in relation to child custody evaluations. The current Guidelines espouse that psychologists have a greater understanding of how biases may impact their work [8].

Problems arise when psychologists are not aware of these biases or are aware and do not take steps to rectify them. In particular, psychologists are susceptible to cognitive biases and unconscious biases that may arise out of countertransference [9-11]. Regarding cognitive biases, the literature has shown that psychologists (like other human beings) are susceptible to biases related to representativeness, which refers to the propensity for an individual to subjectively estimate the probability of an event or sample based on how similar it is to other events or samples, availability, which refers to the tendency for an individual to overestimate how likely an event may occur based on how easily they are able to recall similar events, and anchoring, which refers to the idea that an individual may be more prone to be influenced by information that is gathered in the beginning of their assessment as opposed to information that is gathered later on [9]. Specific to psychologists, however, the biases that psychologists may be susceptible to are confirmatory bias or confirmation bias, hindsight bias, and familiarity bias [9,10]. These are implicit, or unconscious biases, which may affect how the data one gathers is interpreted [9,10]. Pickar discussed that because of the nature of a psychologist’s work, they may also be susceptible to biases caused by countertransference [11].

Pickar argued that due to the very nature of a child custody evaluation being a significant and often emotional experience not only for those who are being evaluated but potentially also for the evaluator, child custody evaluators may be particularly susceptible to having unconscious feelings activated throughout the process [11]. The effect of countertransference may vary depending on the psychologist’s own life experiences and how the current evaluation is aligning with these life experiences.

Biases are often rooted in prejudicial ideas regarding race and gender [12,13]. Gender bias has a long-standing history and there are several common biases that emerge [14]. Historically, these include: women are more likely to be diagnosed with histrionic personality disorder than males even when presenting with the same symptoms, males are more likely than women to be diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder even when presenting with the same symptoms, and women are more likely to be diagnosed with depression while men are more likely to be diagnosed with an “organic mental disorder” even when presenting with the same symptoms [15]. Additionally, one study found that women may be viewed to be less competent to make their own decisions when compared to their male counterparts [14]. It is also important to consider the impact of the interaction between gender and race, particularly regarding African American females. Negative stereotypes of African American women often portray them as being “jezebels,” “welfare queens,” and angry [16,17]. Considering that one of the main referral reasons for a child custody evaluation is the mental instability of a parent, understanding how gender biases may be impacting child custody evaluators is incredibly important to ensure that any clinical conclusions regarding diagnosis of the parents is based in reality and not due to unconscious gender bias.

Another realm of bias that can be relevant in a given case is racial bias. Racial bias has also been studied substantially within the field of psychology. However, there are, as with gender bias, several salient biases that have been consistently found regarding the perception of African American males. African American males are often thought and portrayed to be angry, aggressive, and violent [18-20]. These negative stereotypes have been shown to exist across public opinion and the media, to the point where “African American male” has become synonymous with “criminal” [18,20,21]. Spector discussed that African Americans are more likely than Whites to be perceived as uncooperative and disturbed, and are therefore, more likely to be restrained in inpatient settings [22]. This perception, in particular, is an example of how unconscious bias may be creeping into the diagnosis and treatment of African Americans due to stereotypes of African Americans being angry and aggressive.

It is also important to note that child custody disputes and evaluations have, historically, been shown to be biased based on the zeitgeist, especially toward mothers. Fabricus, Braver, Diaz, and Velez reported that 83% of the public perceives the system to favor mothers [23]. This may be due to the fact that one of the oldest standards for child custody decisions was the “tender years” doctrine, whereby mothers were granted custody automatically to young children based on the belief that young children needed their mothers [24]. The current standard, which effectively was supposed to counter the bias perceived by the tender rule’s doctrine, is to make a custodial decision based on the best interests of the child [25]. The APA has also weighed in on the standard for which to make custodial decisions and dictates that the evaluator must decide based on the psychological best interest of the child [8]. However, the best interest standard has also been criticized as being biased against mothers such that after a divorce, many mothers become single parents and have less economic resources than the fathers [25]. Given that the system as a whole has historically been shown to exude biases in its child custody decisions, it is that much more important that the psychologists who perform child custody evaluations are preparing an evaluation and ultimately giving recommendations that are based on fact and are not unconsciously influenced by their own biases.

Statement of the Problem

The primary purpose of this study is to quantitatively assess how psychologists’ conscious or unconscious biases based on the race and gender of the individual in question may affect the judgment of several salient factors that are common issues in child custody evaluations. This area of research is of particular importance first because it has not been studied in the literature. Second, because of the huge impact a child custody evaluation will likely make on a child’s (and family’s) future. With approximately 94% of child custody evaluators answering the ultimate issue for the court (i.e., making explicit recommendations about who should have custody), it is imperative that they reach these conclusions at the end of an unbiased assessment [3]. Considering child custody evaluations should be assessing for what will ultimately be in the best interest of the child, it is of utmost importance that evaluators are objective in their work.

This study not only assessed for potential biases of psychologists who routinely conduct child custody evaluations, but also included psychologists who do not perform child custody evaluations. While all psychologists should embody competence and be aware of their own biases, those who conduct child custody evaluations are required to obtain a higher degree of competency relating to their role as a child custody evaluator. After the American Psychological Association’s 1994 publishing of Guidelines for Child Custody.

Evaluations in Family Law Proceedings (updated in 2010), those psychologists who routinely conduct child custody evaluations should have specialized competence in this area [8]. Their competence should extend to a greater ability to remain unbiased, and thus would be expected to be less vulnerable to biases than psychologists who do not do child custody evaluations. As the APA Guidelines for Child Custody Evaluations in Family Law Proceedings denote, bias on the part of child custody evaluators is “likely to interfere with data collection and interpretation and thus with the development of valid opinions and recommendations” [8].

In order to evaluate for potential racial and gender biases, 50 licensed psychologists who do and do not conduct child custody evaluations were randomly assigned to a vignette about a hypothetical parent who is requiring a child custody evaluation. There were four vignettes, all of which contained the same information. However, the gender and race of the parent was varied. Therefore, the participant was randomly assigned to one of the following conditions: White parent, Black parent, male parent, or female parent. The participant would then rate how positive the person depicted is on several factors in their evaluation of that person in the child custody case, using a 7-point Likert scale. The factors rated come from Bow and Quinnell’s study, which is based on the Michigan Best Interests of the Child Criteria [3]. It is these factors that remain constant throughout the vignettes.

While the literature has examined racial and gender bias within the treatment and diagnosis of psychological patients at large, as well as how child custody proceedings as a whole may be biased, there is a significant paucity of research that examines biases specifically in relation to child custody evaluators. While a couple of studies did look at bias in child custody evaluators, the only biases considered were cognitive biases and the implicit, unconscious effects of countertransference [10,11]. In addition, those studies are over a decade old. Further, those were qualitative commentary and not quantitative studies.

It was the intention of this current study to fill that gap in the literature. First, the current study adds quantitative data to the existing body of literature regarding biases of psychologists in general. Second, the current study considers two major areas of potential bias that have not previously been examined in relation to child custody evaluators: race and gender. Third, the current study not only evaluates for bias of psychologists who routinely conduct child custody evaluations but also evaluates for biases of psychologists who do not conduct child custody evaluations, allowing for comparisons between the two that have yet been made. Such examination allows a determination of whether such biases, if they exist, are common to psychologists or are not an issue for those doing child custody evaluations. By gaining a better understanding of what biases may be present for psychologists who routinely conduct child custody evaluations, the current study contributes to the field by providing a starting point for a larger discussion of how these biases may be impacting custody decisions. Additionally, if these implicit biases become explicit, they can begin to be addressed and mitigated.

Methods

Participants

Fifty psychologist participants were included in this study. The respondents were required to be licensed psychologists in the state of California. There were no restrictions to age, gender, or ethnicity. The sampling procedure used was a convenience sample. A summary of the study with inclusion criteria and a link to the survey was posted on the Orange County Psychological Association website, the Los Angeles County Psychological Association Listserv, and the San Diego Psychological Association website. The researcher requested permission to post on these ListServs and obtained written permission from each Association expressing this permission. In addition, the public lists of psychologists on the Family Court panels for child custody evaluations was accessed, and individual letters of recruitment were sent to these professionals. Additional recruitment letters were sent to psychologists on the public list of court approved custody evaluators addressed to them in their county. The mean age of these participants was 56.85 (SD=14.632, Range=30 – 88). Other demographic information is provided below. Possibly due to the small sample size, no differences were detected for any of the following demographic variables.

Ethnicity of Participants: Forty-four participants identified as Caucasian/White, two participants identified as Asian/Asian American, and one participant identified as Hispanic. Three participants did not respond to this demographic question.

Degrees Held by Participants: Thirty-six participants indicated they held a Ph.D. and 10 participants indicated they held a Psy.D. Four participants did not respond to this demographic question.

Counties in Which Participants Currently Practice: Twentyeight participants currently practice in Los Angeles County and nine participants currently practice in Orange County. One participant currently practices in each of the following counties: San Bernardino County, Contra Costa County, Sonoma County, Santa Clara County, and San Diego County. One participant indicated only that they practice in the United States of America. Seven participants did not respond to this demographic question.

Diplomate Status of Participants: Six participants hold American Board of Professional Psychology (ABPP) diplomate status, 41 do not hold ABPP diplomate status, and four participants did not respond to this demographic question. Only two participants indicated that they are Board Certified Forensic Psychologists. All fifty participants indicated that they belong to at least one Psychological Association.

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire: The respondents were asked to complete a demographic questionnaire that was included as part of the online survey and was given following a vignette. This is so that the participants were not primed to age and gender prior to responding to the vignette. The demographic questionnaire asked for gender, ethnicity, years practicing as a licensed psychologist, whether or not they conduct child custody evaluations, how many years they have been conducting child custody evaluations (if applicable), and how many such evaluations they estimate they have conducted if they have conducted evaluations.

Vignette: Four vignettes were constructed that vary in one detail only. The vignettes were about one of the parents in a child custody dispute. The parent was either described as a woman, a man, an African American or a Caucasian. The vignette included information that is commonly considered in child custody evaluations. The participants then rated how positive the person depicted is on several factors in their evaluation of that person in the child custody case. The factors rated come from Bow and Quinnell’s [3] study, which was based on the Michigan Best Interests of the Child Criteria. Therefore, the vignette referenced education, employment, disciplining behavior, alcohol use, attachment with the child(ren), willingness to facilitate the parent-child relationship, presence and impact of family violence, and mental health status. All four vignettes contained the same information about the parent. There were four conditions (4 variations of the description of the parent): White parent, Black parent, Male parent, and Female parent.

Procedures

The psychologists who respond to the recruitment letter by accessing the SurveyMonkey link in the recruitment letter saw the Informed Consent. Their consent to participate was indicated by clicking “I consent,” which then presented them the vignette. After the Informed Consent message, they were presented a vignette and associated questions. After completing the questions, they were asked to complete a demographic questionnaire. They were then presented with the Debriefing Statement. The demographic questionnaire and vignette took approximately 15 - 20 minutes to complete.

In addition, all the information that is gathered was anonymous; no identifying information was obtained, and the demographic questionnaire was separated from the general survey information. All information collected was kept on a password protected. In addition, the data will be kept for a minimum of five years after completion per APA guidelines, and then subsequently destroyed via uploading all relevant data onto a flash drive, thereby removing it from the computer’s hard drive, and then destroying the flash drive. Upon completion of the survey, each respondent received a digital debriefing statement with the senior researcher’s contact information. This debriefing statement was included as the final portion of the online survey and contained follow-up referrals and researcher’s contact information. Also, respondents were notified that their voluntary participation in this research study resulted in a $5.00 donation to the Orangewood Foundation for Children for each completed survey as a token of appreciation for their participation.

Results

Personal Characteristics Affecting Assessment of the Parents

There were nine Personal Characteristics that could have affected the psychologists’ assessment of each parent. Each characteristic was evaluated by a pair of questions: How heavily would you weigh that characteristic, and how much did it hurt or help the parent. The results have been organized into 3 major sections, each with several sub-sections. These sections are titled: Parent Demographic Variables (Age, Education, and Occupation), Parent-Child Interaction Variables (Use of Corporal Punishment and Parents’ Verbal Argument), and Parent Mental Health Variables (Alcohol Use, Depression, Treatment Compliance, and Remission).

Almost all of the significant findings related to how much weight the psychologist participant indicated they would give to a particular characteristic. There were only two areas in which there were significant effects regarding the ratings the participants gave as to how much a characteristic helped the parent: Occupation and medication compliance. Between these two areas, there were three significant main effects and 12 significant interaction effects. Therefore, those fifteen significant effects on how much the differentially weighted characteristic helped will be inserted where they coincide with the characteristic being rated as being differentially weighted.

To anticipate the Discussion Chapter, and to give a possible overriding structure to the many significant effects, the reader may discern that it seems as though the psychologist participants thought that a number of parent characteristics should be weighed heavily, but rarely did that weighting mean that the characteristic by itself helped or hurt the parent. Thus, it is almost as though the participants were saying: These are important characteristics for this parent, and so it is as if they go into some unspecified formula to be completed/computed later.

Because of the small number of participants who have conducted child custody evaluations, there is concern about missing possible significant differences (Type II Errors: Concluding that a difference does not exist when one does exist). Therefore, p levels less than .06 will be reported, rather than being confined to the more traditional .05 level. Also, because of the small number of participants who have conducted child custody evaluations, there is one cell of the experimental design in which there are not any participants. The final consequence of the small number of participants who have conducted child custody evaluations is that it was possible to conduct 2-way interaction effects, such as having conducted evaluations in combination with gender of the psychologist, to further specify some of the significant main effects, but 3-way interactions, such as having conducted evaluations, gender of the psychologist and gender or ethnicity of the parent, could not be computed, and so that degree of specificity was not possible.

Parent Demographic Characteristics

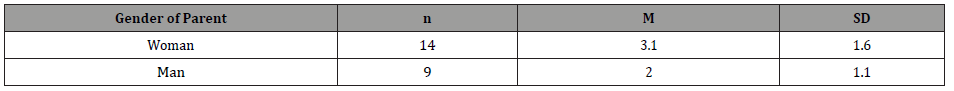

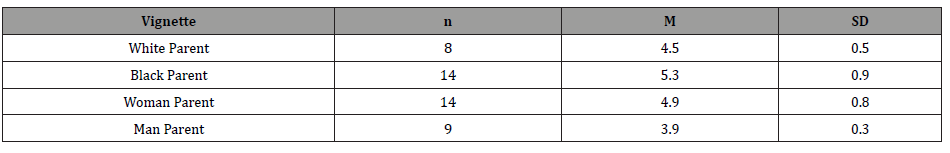

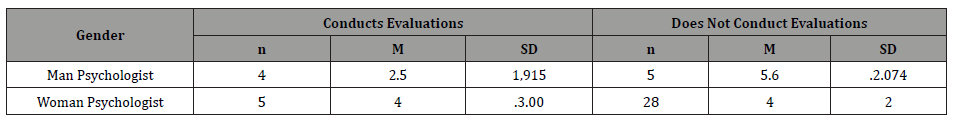

Parent’s Age: How Heavily Was It Weighed: There was a main effect of vignette on how heavily age was weighed (F (3,41)=2.69, p=.059). Post hoc analyses revealed that there were no significant differences regarding how heavily age was weighted between whether the parent was described as Black or White. There was, however, a significant difference on how heavily age was weighted when the parent was described as a Man or Woman (p=.052). The means and standard deviations can be seen in Table 1. It can be seen in Table 1 that the age of the parent was weighed significantly more heavily when the parent was described as being a Woman (M=3.1) than when the parent was described as being a Man (M=2 .0).

Table 1: Means and Standard Deviations for How Heavily the Participant Weighted the Gender of the Parent’s Age

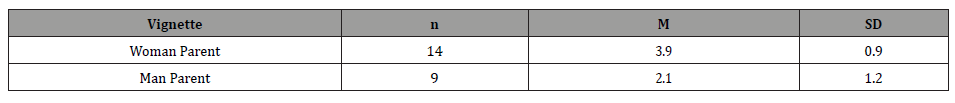

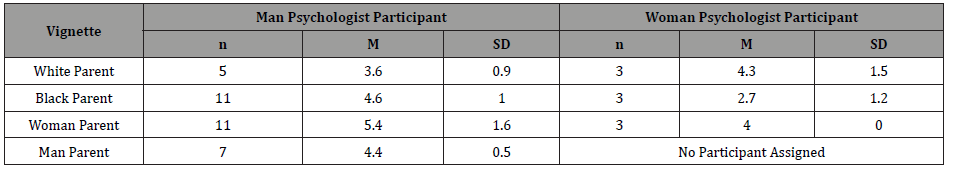

Parent’s Education: How Heavily Was It Weighted: There was a main effect of vignette on how heavily the parent’s education was weighed (F (3,41)=4.16, p=.012). Post hoc analyses revealed there was not a significant difference between whether the parent was described as Black or White as to how heavily parent’s education was weighted, but there was a significant difference regarding how heavily education was weighted between whether the parent was described as a Man or a Woman (p=.052). The means and standard deviations can be seen in Table 2. It can be seen in Table 2 that the parent’s education was weighted more heavily when the parent was described as being a Woman (M=3.9) than when the parent was described as being a Man (M=2.1).

Table 2: Means and Standard Deviations for How Heavily the Participant Weighted the Gender of the Parent’s Age

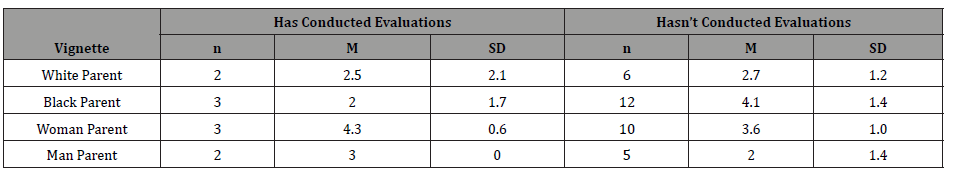

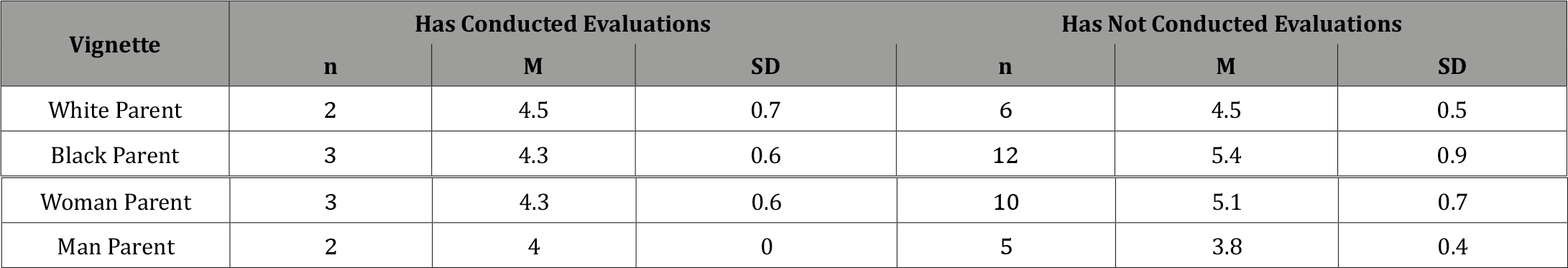

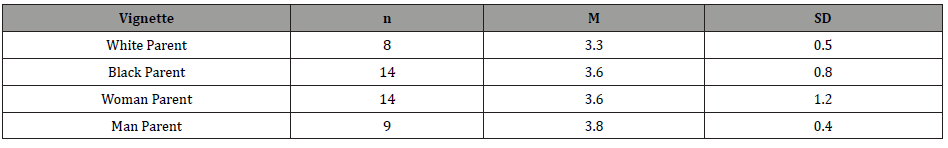

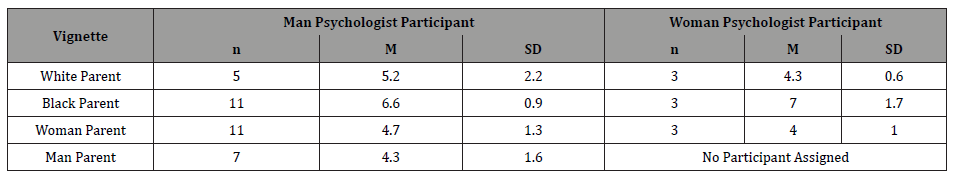

Interaction of Gender of Parent and Experience Doing Child Custody Evaluations on Weighting of Education: There was an interaction effect of whether or not the participant had conducted child custody evaluations and the vignette on how heavily parent’s education was weighed (F (7,35)=2.58, p=.029). Post hoc analyses revealed several significant differences between combinations of whether or not the psychologist has conducted child custody evaluations and the specific vignette. The means and standard deviations of the eight combinations of having done child custody evaluations and specific vignettes can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3: Means and Standard Deviations for Combinations of Whether the Psychologist Participant Has Conducted Child Custody Evaluations and Vignette on How Heavily Parent Education Weighted.

Parent Gender and Child Custody Evaluation Experience: In regard to gender of the parent, psychologists who have conducted child custody evaluations and responded to the Woman parent vignette weighed parent’s education (M=4.3) significantly more heavily (p=.016) than psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations and who responded to the Male parent vignette (M=2.0). Psychologist participants who have not conducted child custody evaluations and responded to the Woman parent vignette (M=3.6) weighed parent’s education significantly more heavily (p=.027) than psychologist participants who have not conducted child custody evaluations and responded to the Male parent vignette (M=2.0).Thus, for these psychologist participants, gender of the parent was a factor for them when the parent is described as a Woman compared to when the parent is described as a Man.

Ethnicity of Parent and Child Custody Evaluation Experience: It can be seen above in Table 3 that psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations and responded to the Black parent vignette (M=4.1) weighed parent’s education significantly more heavily (p=.031) than psychologist participants who have not conduct child custody evaluations and responded to the White parent vignette (M=2.7), and rated education more heavily (p=.015) than those psychologists who have conducted child custody evaluations and responded to the Black parent vignette (M=2.0). Thus, education of the parent was deemed as a heavier factor by those who have not conducted child custody evaluations and read the Black parent vignette than did those who have not conducted child custody evaluations and read the White parent vignette, and more heavily than those who have conducted child custody evaluations and read the Black parent vignette.

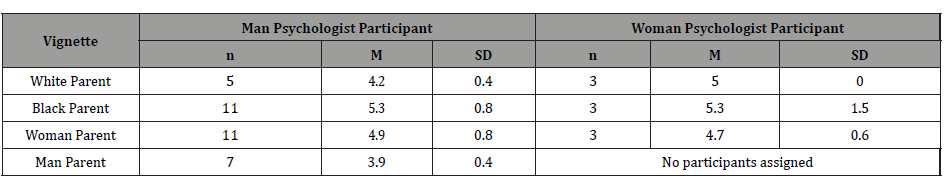

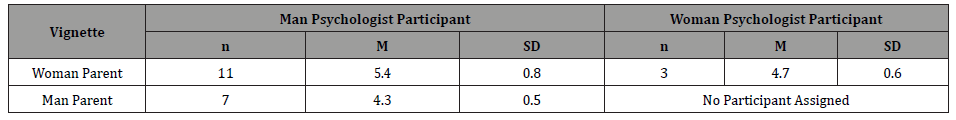

Parent Education Ratings, Vignette and Gender of Psychologist: There also was an interaction effect of gender of psychologist participant and vignette on how heavily parent’s education was weighed (F (6,36)=3.11, p=.015). Post hoc analyses revealed several significant differences between combinations of gender of participant and the specific vignette. The means and standard deviations for each of the eight combinations of gender of the psychologist participant and each of the four vignettes are presented in Table 4.

Table 4: Means and Standard Deviations for Combinations of Gender of the Psychologist Participant and Vignette on Weighting of Education.

Gender of Psychologist and Ethnicity of the Parent on Weighing Parent’s Education: It can be seen in Table 4 above that Men psychologists who responded to the Black parent vignette weighed parent’s education (M=4.4) significantly more heavily (p=.011) than Men psychologists who responded to the White parent vignette (M=2.2), and significantly more heavily (p=.018) than Women psychologists who responded to the Black parent vignette (M=2.0).

Gender of the Psychologist and Gender of the Parent on Weighing Parent’s Education: Also, in regard to gender of the parent, it can be seen in Table 3 above that Men psychologists who responded to the Woman parent vignette (M=3.7) weighed the Woman parent’s education significantly more heavily (p=.022) than men psychologists who responded to the Man parent vignette (M=2.3). Similarly, women psychologists who responded to the Woman parent vignette (M=4.3) also weighed parent’s education significantly more heavily (p=.022) than men psychologists who responded to the Man parent Vignette (M=2.3). Thus, both the Men and Women psychologist participants rated the Woman parent’s education more heavily than did the Men psychologists rating of the parent described as a Man.

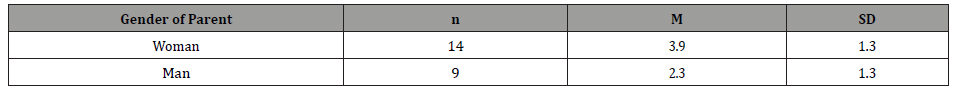

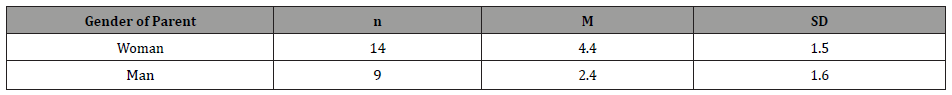

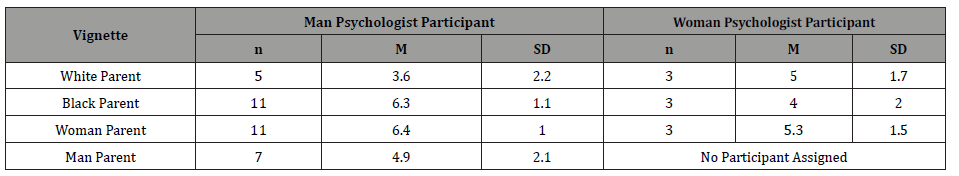

Parent’s Occupation: How Heavily Was It Weighted: There was a main effect of vignette on how heavily parent’s occupation was weighted (F (3, 41)=2.83, p=.050). The means and standard deviations can be seen in Table 5. Post hoc analyses revealed that there were significant differences between whether the parent was described as a Woman or Man on how heavily parent’s occupation was weighed (p=.015). It can be seen in Table 6 that the parent’s occupation was weighted significantly more heavily when the parent was described as a Woman (M=3.9) than when the parent was described as a Man (M=2.1). As will be repeated below in greater detail and presented in Table 6, parent’s occupation was also rated as being more helpful when the parent was described as a Woman (M=3.9) than when the parent was described as a Man (p=.019).

Table 5: Means and Standard Deviations for Occupation as to How Heavily the Participant Weighted the Gender of the Parent.

Table 6: Means and Standard Deviations for How the Participants Rated the Helpfulness of Occupation for the Gender and Ethnicity of the Parent.

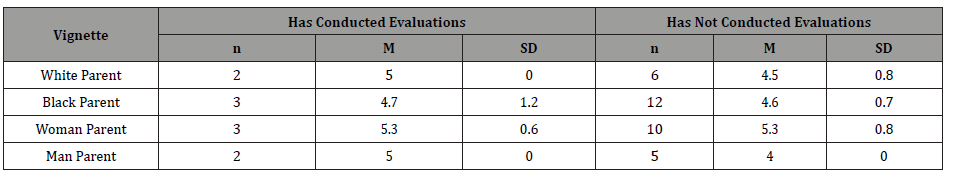

How Much Did Parent’s Occupation Help or Hurt? There was a main effect of vignette on how much parent’s occupation helped or hurt (F(3,41)=7.22, p=.001). The means and standard deviations can be found in Table 6. Post hoc analyses of how much the parent’s occupation helped revealed significant differences between whether the parent was described as a Woman or a Man (p=.019), as indicated above and whether the parent was described as Black or White (p=.003). It can be seen in Table 6 that the parent’s occupation was rated as helping significantly more when the parent was described as a Woman (M=4.9) than when the parent was described as a Man (M=3.9). Parent’s occupation also helped significantly more when the parent was described as Black (M=5.3) than when the parent was described as White (M=4.5). Thus, both the ethnicity and gender of the parent being described were factors in how much the parent’s occupation helped in the ratings by the psychologist participants. In other words, the occupation assigned to the parent was rated as more helpful to the Woman parent and to the Black parent.

Interaction of Experience Doing Child Custody Evaluation and Parent Ethnicity on Helpfulness of Parent Occupation: In addition to the main effect of ethnicity on how helpful the parent’s education was, there was also an interaction effect of whether or not the participant has conducted child custody evaluations and ethnicity of the parent on how much parent’s occupation helped (F (7,35)=3.82, p=.003). The means and standard deviations of the eight combinations of having done child custody evaluations (yes or no) and the four specific vignettes are presented in Table 7. Post hoc analyses revealed several significant differences between combinations of whether or not psychologist participants have conducted child custody evaluations and the specific vignette.

It can be seen in Table 7 that psychologist participants who have not conducted child custody evaluations and responded to the Black parent vignette rated occupation (M=5.4) as helping significantly more (p=.015) than psychologist participants who do not conduct child custody evaluations and responded to the White parent vignette (M=4.5). Thus, for these psychologists who do not conduct child custody evaluations, the ethnicity of the parent was a factor when the parent was described as Black, but not when the parent was described as White. Specifically, these psychologists who have not conducted custody evaluations rated that the occupation was more helpful to the Black parent than it was for the White parent. Additionally, psychologist participants who have not conducted child custody evaluations and responded to the Black parent vignette rated occupation (M=5.4) as helping significantly more (p=.025) than psychologist participants who have conducted child custody evaluations and responded to the Black parent vignette (M=4.3). In other words, psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations rated the occupation of the Black parent as more helpful than it was for a White parent, and as more helpful for the Black parent than did those who have conducted child custody evaluations.

Table 7: Means and Standard Deviations for Combinations of Whether the Psychologist Participant Conducts Child Custody Evaluations and Vignette on How Helpful Occupation Was.

Interaction of Gender of Parent and Experience Doing Child Custody Evaluations on Helpfulness of Parent Occupation: There was also an interaction of the gender of the parent and whether the psychologist had conducted child custody evaluations on how helpful the occupation was (F (7,35)=2.58, p=.029). The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 7 above. Those psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations and responded to Woman parent vignette rated occupation (M=5.1) as helping significantly more (p=.055) than psychologist participants who conduct child custody evaluations and responded to the Man parent vignette (M=4.0), and significantly more (p=.002) than psychologists who do not conduct child custody evaluations and responded to the woman parent vignette (M=3.8). Thus, for the psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations, gender of the parent was a factor when the parent was described as a Woman, but not when the parent was described as a Man.

Gender of Psychologist and Vignette on How Much Occupation Helped: There was also an interaction effect of gender of the psychologist and the vignette viewed on how much parent’s occupation helped or hurt (F (6,36)=3.46, p=.008). The means and standard deviations for each of the eight possible combinations of gender of the psychologist participant and each of the four vignettes can be found in Table 8 (none of the Women psychologists were given the Man parent vignette by SurveyMonkey, so that cell of the design did not have any participants). Post hoc analyses revealed several significant differences between combinations of gender of participant and specific vignette. It can be seen in Table 8 that Men psychologist participants who responded to the Black parent vignette rated parent’s occupation as helping (M=5.3) significantly more (p=.012) than Men psychologist participants who responded to the White parent vignette (M=4.2). Women psychologist participants who responded to the Black parent vignette also rated parent’s occupation (M=5.3) as helping significantly more (p=.045) than did Men psychologist participants who responded to the White parent vignette (M=4.2).

Table 8: Means and Standard Deviations on How Much Occupation Helped for Combinations of Gender of the Psychologist Participant and Vignette.

Table 7 showed that overall, occupation was rated as more helpful to the parent described as Black. However, Table 8 shows that this finding was the result of both the men and women psychologists rating occupation as more helpful for the Black parent than for the white parent. Regarding gender of parent, Men psychologist participants who responded to the Woman parent vignette rated parent’s occupation (M=4.9) as helping significantly more (p=.006) than did Men psychologist participants who responded to the Man parent vignette (M=3.9). Thus, for these Men psychologists, occupation was more helpful to the Woman parent than it was for the parent described as a Man.

Specific Aspect of Occupation - Working a Day Shift: How Heavily Weighed: There was a main effect of vignette on how heavily the parent working a day shift was weighted (F(3,41)=4.16, p=.012). The means and standard deviations are in Table 9.

Table 9: Means and Standard Deviations for How Heavily the Participant Weighted Working a Day Shift in regard to the Gender of the Parent.

Post hoc analyses revealed that there was a significant difference on how heavily the parent working the day shift was weighted depending on whether the parent was described as a Man or Woman (p=.006). It can be seen in Table 9 that the parent working the day shift was weighted significantly more heavily when the parent was described as a Woman (M=4.4) than when the parent was described as a Man (M=2.4). It should also be noted that the mean rating for the Woman parent is above the mid-point of the scale, meaning working day shift was seen not only as more important for the woman, but since the rating for the man is below the mid-point, that means that working the day shift was rated as not important for the man parent.

Interaction of Psychologist Gender and Having Done Custody Evaluations on How Heavily Being Day Shift Worker Was Weighted: There was a significant interaction effect of gender of the psychologist participant and whether or not the psychologist has conducted child custody evaluations on how heavily the parent being described as working the day shift was weighted (F (1,39)=4.27, p=.046). The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 10.

It can be seen in Table 10 that Man psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations weighed the parent working a day shift more heavily than any other group, although the Women psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations were the second highest in weighing this factor.

Table 10: Means and Standard Deviations for How Heavily the Participant Weighted Working a Day Shift in regard to the Gender of the Parent.

Helpfulness Ratings for Working the Day Shift Gender of parent, gender of psychologist and vignette on helpfulness of working day shift: There was an interaction effect of gender of psychologist participant and vignette on how much the parent being a day shift worker helped or hurt (F (6,36)=2.81, p=.024). Post hoc analyses revealed significant differences between the 8 possible combinations of gender of participant and the specific vignette. The means and standard deviations for each of the combinations of gender of the psychologist participant and of gender of the parent can be seen in Table 11. It can be seen in Table 11 that Man psychologist participants who responded to the Woman parent vignette rated the parent being a day shift worker (M=5.4) as being significantly more helpful (p=.003) than did Man psychologist participants who responded to the Man parent vignette (M=4.3).

Table 11: Means and Standard Deviations for Combinations of Gender of the Psychologist Participant and Vignette.

Interaction effect of conducting child custody evaluations and vignette on helpfulness of working the day shift: There was also an interaction effect of whether or not the participant has conducted child custody evaluations and vignette on how much the parent being a day shift worker helped or hurt (F(7,35)=2.58, p=.029). The means and standard deviations of the eight possible combinations of having done child custody evaluations and specific vignettes are presented in Table 12. Post hoc analyses revealed significant differences between combinations of whether or not psychologist participants have conducted child custody evaluations and the specific vignette.

Table 12: Means and Standard Deviations for Combinations of Whether the Psychologist Participant Conducts Child Custody Evaluations and Vignette.

It can be seen in Table 12 that psychologist participants who have conducted child custody evaluations and responded to the Woman parent vignette rated the parent being a day shift worker (M=5.3) significantly more helpful (p=.015) than did psychologist participants who have not conducted child custody evaluations and responded to the Man parent vignette (M=4.0). This was also seen with psychologist participants who have not conducted child custody evaluations and responded to the Woman parent vignette (M=5.3), as these participants also rated the parent being a day shift worker significantly more helpful (p=.002) than psychologist participants who have not conducted child custody evaluations and responded to the Man parent vignette (M=4.0). Thus, working the day shift was considered as more helpful to the Woman parent by both those who have and those who have not conducted child custody evaluations, and further those who have not conducted child custody evaluations rated a Woman parent working the day shift was much more helpful to her than a Man parent working the day shift.

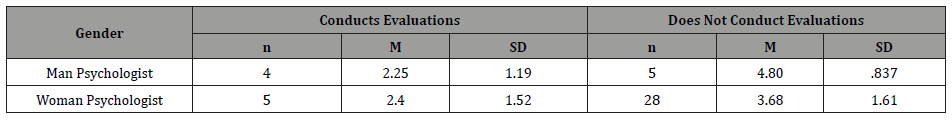

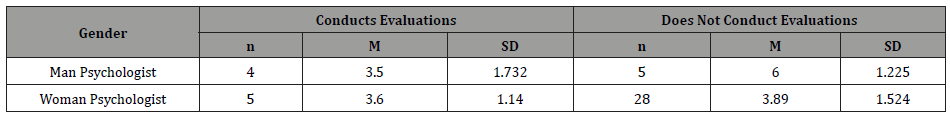

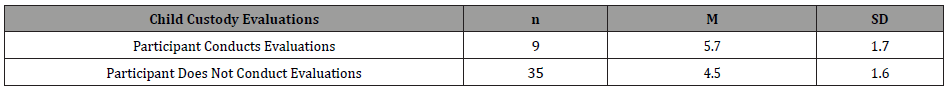

Parent-Child Interactions

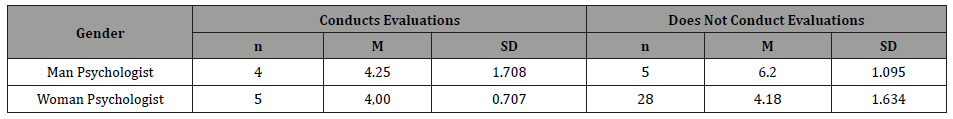

How Heavily Was Parent’s Occasional Corporal Punishment Use Weighted: There was a main effect of whether or not the psychologist participant has conducted child custody evaluations on how heavily the parent’s occasional corporal punishment was weighted (F (1,42)=4.35, p=.043). The means and standard deviations can be seen in Table 13. It can be seen in Table 13 that participant psychologists who do not conduct child custody evaluations (M=4.7) weighted the parent’s occasional corporal punishment use more heavily than did the psychologists who have conducted child custody evaluations (M=3.7).

Table 13: Means and Standard Deviations for How Heavily the Participant Weighted the Parent’s Occasional Corporal Punishment

Psychologist Gender and Vignette Interaction on Weighting of Occasional Use of Corporal Punishment: There was, however, a significant interaction effect of gender of the psychologist and vignette on how heavily the parent’s occasional corporal punishment use was weighted (F(6,36)=2.92, p=.020). The means and standard deviations for each of the eight possible combinations of gender of the psychologist participant and each of the four vignettes can be seen in Table 14. Post hoc analyses revealed significant differences between combinations of gender of psychologist and the specific vignette. It can be seen in Table 14 that Men psychologists who responded to the Black Parent vignette rated the parent’s occasional use of corporal punishment (M=4.6) significantly heavier (p=.017) than did Woman psychologists who responded to the Black parent vignette (M=2.7). It should be noted that these mean ratings indicate that the Women psychologists rated the Black parent’s occasional use of corporal punishment not only as less heavily than did the Man psychologists, but they rated it as unimportant, whereas the Men psychologists rated the occasional use of corporal punishment by the Black parent as an important factor.

Table 14: Means and Standard Deviations for Combinations of Gender of the Psychologist Participant and Vignette for Occasional Use of Corporal Punishment.

Parent’s History of Verbal Arguments: How Heavily Was It Weighted Interaction Effect of Gender of Psychologist and Experience Doing Child Custody Evaluations on How Heavily a History of Verbal Arguments was Weighted: There was a significant interaction effect of gender of psychologist and whether or not the psychologist has conducted child custody evaluations on how heavily the parent’s history of verbal arguments was weighted (F(1,39)=10.93, p=.002). The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 15.

Table 15: Means and Standard Deviations for Combinations of Gender of the Psychologist and Whether or Not They Conduct Child Custody Evaluations on How Heavily the History of Verbal Arguments was Weighted.

It can be seen in Table 15 that Man psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations weighted more heavily than any other group the history of there being verbal arguments between the parents.

History of Children Hearing the Verbal Arguments: How Heavily Weighted: There was a main effect of whether or not the psychologist had conducted child custody evaluations on how heavily the history of the children hearing the verbal arguments was weighted (F(1, 42)=4.43, p=.041). The means and standard deviations can be seen in Table 16.

It can be seen in Table 16 that psychologists who conduct child custody evaluations weighted the history of the children hearing the verbal arguments (M=5.3) significantly heavier than psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations (M=4.1).

Table 16: Means and Standard Deviations for Those Who Have and Those Who Have Not Conducted Child Custody Evaluations for How Heavily the Participant Weighted the History of the Children Hearing Verbal Arguments.

Parent Mental Health Issues

Parent Use of Alcohol

How Heavily Was Parent’s Alcohol Use Weighted?

Gender of Psychologist and Vignette Interaction on Alcohol

Use: There was an interaction effect of gender of psychologist

participant and vignette on how heavily the parent’s alcohol use

was weighted (F(6,36)=3.20, p=.013). The means and standard

deviations for each of the combinations of gender of the psychologist

participant and the two ethnicities of the parent can be seen in

Table 17. Post hoc analyses revealed significant differences between

combinations of gender of psychologist and the specific vignette.

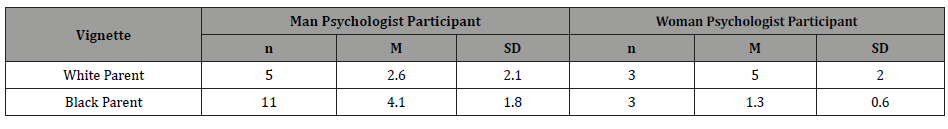

Table 17: Means and Standard Deviations for Combinations of Gender of the Psychologist Participant and Vignette on Weighting of Alcohol Use.

In regard to ethnicity of the parent, it can be seen in Table 13 that Woman psychologists who responded to the White parent vignette weighted parent’s alcohol use (M=5.0) significantly heavier (p=.040) than Men psychologist participants who responded to the White parent vignette (M=2.6), and significantly heavier than Woman psychologist participants who responded to the Black parent vignette (M=1.3). Men participants who responded to the Black parent vignette weighted the parent’s alcohol use (M=4.1) significantly heavier (p=.010) than Women participants who responded to the Black parent vignette (M=1.3). Considering the magnitude of the means in comparison to the mid-point of the scale, the Women psychologists heavily weighed the use of alcohol use by the White parent but rated the alcohol use of the Black parent as unimportant, whereas the Men psychologist participants rated the alcohol use of the White parent as unimportant (below the mid-point of the scale) but rated the alcohol use of the Black parent as important (rated heavily). Thus, in regard to ethnicity, the Men and Women psychologist participants were exactly opposite in their attitudes regarding alcohol use by the White parent compared to the Black parent. This pattern was similar to that reported above in regard to use of corporal punishment such that the women psychologists rated both the alcohol use and corporal punishment by the Black parent as unimportant, whereas the men psychologists rated both the alcohol use and corporal punishment by the Black parent as important factors in their assessment of the parent.

Interaction of Gender of Psychologist and Experience Doing Child Custody Evaluations on Weightings of Alcohol Use: There was a significant interaction effect of psychologist gender and whether or not the participant conducts child custody evaluations on how heavily the parent’s alcohol use was weighted (F(1,39)=5.21, p=.028. The means and standard deviations for the four combinations of gender of psychologist and whether or not they have conducted child custody evaluations are presented in Table 18.

Table 18: Means and Standard Deviations for Combinations of Gender of the Psychologist and Whether or Not They Conduct Child Custody Evaluations on Weighing Alcohol Use.

It can be seen in Table 18 that the Man psychologists who conducted child custody evaluations weighed the use of alcohol the least of any group, whereas the Man psychologists who had not conducted child custody evaluations weighed the use of alcohol the most heavily. In contrast the Women psychologists weighed alcohol use at the same magnitude whether they had conducted child custody evaluations or not.

Parent’s Depression

How Heavily Was Parent Receiving Treatment for

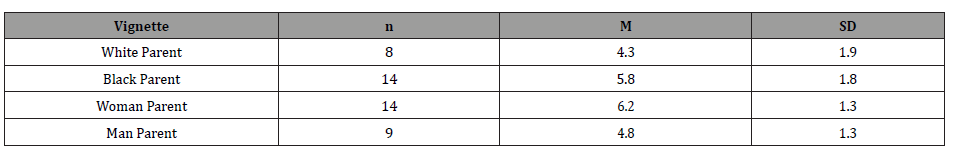

Depression Weighted: There was a main effect of vignette on how

heavily the parent receiving treatment for depression was weighted

(F(3,41)=3.65, p=.020). The means and standard deviations can

be seen in Table 19. Post hoc analyses revealed that there are

significant differences between whether the parent was described

as Black or White (p=.027), and whether the parent was described

as a Man or Woman (p=.028).

Table 19: Means and Standard Deviations for How Heavily the Participant Weighted the Gender and Race of the Parent.

It can be seen in Table 19 that the parent receiving treatment for depression was weighted significantly more heavily when the parent was described as a Black (M=5.8) than when the parent was described as White (M=4.3), and when the parent was described as a Woman (M=6.2) than when the parent was described as a Man (M=4.8). However, the psychologist participants did not rate the parent receiving treatment for depression as differentially being helpful nor hurtful based on the gender or ethnicity of the parent.

Interaction of Psychologist Gender and Vignette on Weighting of the Parent Having Received Treatment for Depression: There was a significant interaction effect of gender of participant and vignette on how heavily the parent receiving treatment for depression was weighted (F(6,36)=2.96, p=.019). The means and standard deviations for each of the eight possible combinations of gender of the psychologist participant and each of the four vignettes can be seen in Table 20. Post hoc analyses revealed significant differences between pairs of gender of participant and the specific vignette.

It can be seen in Table 19 that Men psychologists who responded to the Black parent vignette rated the parent receiving treatment for depression (M=6.3) significantly heavier (p=.003) than Men psychologists who responded to the White parent vignette (M=3.6), and significantly heavier (p=.031) than Woman psychologists who responded to the Black parent vignette (M=4.0). Regarding gender of the parent, Men psychologists who responded to the Woman p aren’t vignette rated the parent receiving treatment for depression (M=6.4) significantly heavier (p=.053) than Men psychologists who responded to the Man parent vignette (M=4.9).

Interaction of Gender of Psychologist and Having Conducted Child Custody Evaluations on How Heavily the Parent Receiving Treatment for Depression Was Weighed: There was, however, a significant interaction effect of gender of participant and whether or not the participant conducts child custody evaluations on how heavily the parent receiving treatment for depression was weighted (F(1,39)=4.17, p=.048. The means and standard deviations for the combinations of gender of the psychologist and having conducted child custody evaluations on how heavily the parent receiving treatment for depression was weighed are presented in Table 21.

Table 20: Means and Standard Deviations for Combinations of Gender of the Psychologist Participant and Vignette on How heavily the Parent Receiving Treatment for Depression was Weighed.

Table 21: Means and Standard Deviations for Combinations of Gender of the Psychologist Participant and Whether or Not They Conduct Child Custody Evaluations on Weighing Treatment for Depression.

It can be seen in Table 21 that Male psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations weighed the history of treatment for depression more heavily than any other group.

How Heavily Was Parent’s History of Medication and Treatment Compliance Weighted? There was a main effect of vignette on how heavily the parent’s history of medication and treatment compliance was weighted (F(3,41)=3.40, p=.026).The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 22.

Post hoc analyses revealed that there are significant differences between whether the parent was described as Black or White (p=.034), and whether the parent was described as a Man or Woman (p=.039). The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 22. It can be seen in Table 22 that the parent’s history of medication and treatment compliance was weighted significantly more heavily when the parent was described as Black (M=5.8) than when the parent was described as White (M=4.3), and when the parent was described as a Woman (M=6.2) than when the parent was described as a Man (M=4.8). However, as reported below only ethnicity, not gender, was seen to be differently helpful by the psychologists.

Table 22: Means and Standard Deviations for How Heavily the Participant Weighted History of Medication and Treatment Compliance for the Gender and Race of the Parent.

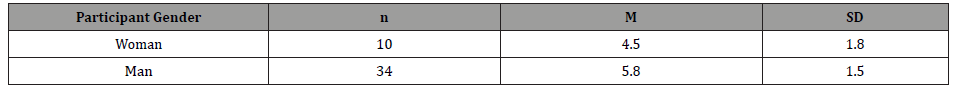

There was also a main effect of gender of the psychologist on how heavily the parent’s history of medication and treatment compliance was weighted (F(1,42)=5.03, p=.030). The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 23. It can be seen in Table 23 that Men psychologists rated the parent’s history of medication and treatment compliance (M=5.8) significantly heavier than did the Woman psychologists (M=4.5).

Table 23: Means and Standard Deviations for How Heavily the Participant Weighted the Parent’s History of Medication and Treatment Compliance.

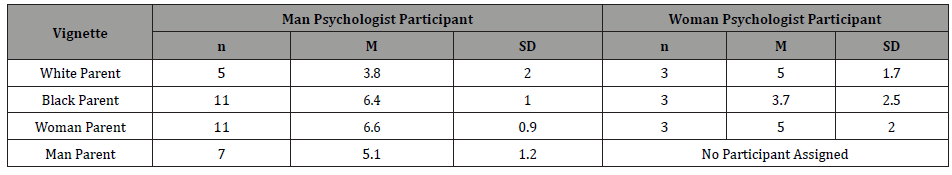

Interaction Effect of Psychologist Gender and Vignette on How Heavily History of Medication and Treatment Compliance Were Weighed: There was a significant interaction effect of gender of participant and vignette on how heavily the parent’s history of medication and treatment compliance was weighted (F(6,36)=3.95, p=.004). Means and standard deviations are presented in Table 24.

Post hoc analyses revealed significant differences between combinations of gender of psychologist and the specific vignette. It can be seen in Table 23 that Men psychologists who responded to the Black parent vignette weighted the parent’s history of medication and treatment compliance (M=6.4) significantly heavier (p=.002) than Men psychologists who responded to the White parent vignette (M=3.8), and significantly heavier (p=.006) than the Woman psychologists who responded to the Black parent vignette (M=3.7).

Regarding gender of the parent, it can be seen in Table 24 that Men psychologists who responded to the Woman parent vignette weighted the parent’s history of medication and treatment compliance (M=6.6) significantly heavier (p=.047) than Men psychologists who responded to the Man parent vignette (M=5.1). Thus, for these psychologists, gender of the parent was relevant to the differential rating of the parent’s history of medication and treatment compliance.

Table 24: Means and Standard Deviations for Combinations of Gender of the Psychologist Participant and Vignette Weighting of the Parent’s History of Medication and Treatment Compliance.

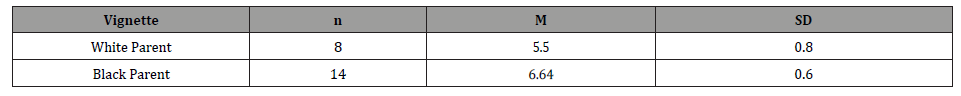

How Much Did Parent’s History of Medication and

Treatment Compliance Help or Hurt?

There was a main effect of vignette on how helpful or hurtful

the parent’s history of medication and treatment compliance was

rated (F(3,41)=3.73, p=.018). Means and standard deviations are

presented in Table 25. Post hoc analyses revealed that there is a

significant difference between whether the parent was described

as Black or White (p=.002). It can be seen in Table 25 that the

parent’s history of medication and treatment compliance was rated

significantly more helpful when the parent was described as Black

(M=6.6) than when the parent was described as White (M=5.5).

Interaction of Psychologist Gender and Vignette on How Much History of Medication and Treatment Compliance Were Helpful or Hurtful: There was a significant interaction effect of gender of psychologist participant and vignette on how heavily the parent’s medication and treatment compliance was weighted (F(6,36)=2.42, p=.045). The means and standard deviations for each of the eight possible combinations of gender of the psychologist and each of the four vignettes can be seen in Table 26.

Post hoc analyses revealed significant differences between combinations of gender of psychologist and the specific vignette. It can be seen in Table 25 that Men psychologists who responded to the Black parent vignette rated parent’s history of medication and treatment compliance (M=6.6) as significantly helping (p=.003) more than Men psychologists who responded to the White parent vignette (M=5.2). Women psychologists who responded to the Black parent vignette also rated parent’s history of medication and compliance (M=7.0) as significantly helping (p=.003) more than Men psychologist participants who responded to the White parent vignette (M=5.2). Thus, medical compliance was weighted as more important for the Black parent (Table 25) and being helpful (Table 26).

Table 25: Means and Standard Deviations for How Heavily the Participant Weighted the Race of the Parent.

Table 26: Means and Standard Deviations for Combinations of Gender of the Psychologist Participant and Vignette on Helpfulness of Treatment Compliance.

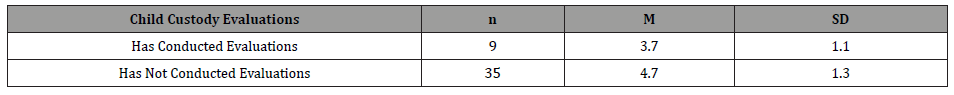

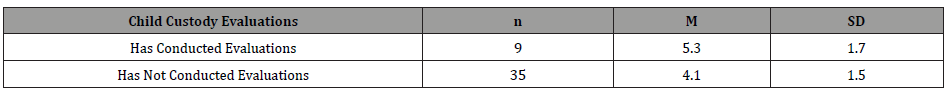

How Heavily Was Parent’s Depression Being in Remission

Weighted?

There was a main effect of whether or not the psychologist had

conducted child custody evaluations on how heavily the parent’s

depression being in remission was weighted (F(1, 42)=3.86,

p=.056). The means and standard deviations can be seen in

Table 27. It can be seen in Table 27 that psychologists who have

conducted child custody evaluations rated the parent’s depression

being in remission (M=5.7) significantly heavier than psychologists

who have not conducted child custody evaluations (M=4.5).

Table 27: Means and Standard Deviations for How Heavily the Participant Weighted the Parent’s Depression Being in Remission.

Discussion

The present study was designed to reveal potential race/ ethnicity and gender biases held by psychologists, which may impact their overall recommendation to the Court regarding child custody issues. Given that psychologists who conduct child custody evaluations should receive extensive competency training, it is presumed that these psychologists would show less of these kinds of biases than those psychologists who do not conduct child custody evaluations. However, given that all psychologists are human and are susceptible to unconscious bias, it was expected that the findings may indicate bias exists, particularly regarding the parent’s race/ethnicity and gender. Therefore, this study focused on those two variables. Overall, results suggest that the participants may have been responding to the items in a way that indicates the importance of specific parental characteristics in the overall evaluation, as opposed to indicating that a specific characteristic is in and of itself weighted in isolation.

Effects of Gender of Parent

For both psychologists who conduct child custody evaluations and those who have not conducted child custody evaluations, education was weighted more heavily when the parent was described as a woman than when the parent was described as a man. This finding coincides with Danzinger and Welfel’s study that found that women may be viewed to be less competent to make their own decisions when compared to their male counterparts [14]. Therefore, the fact that the women parent’s education was weighted more heavily than when the parent was described as a man may be suggestive that these psychologist participants viewed this as being evidence that a woman may be competent to make her own decisions, whereas men’s education was not weighed heavily because it is assumed he is already competent.

Psychologists who conduct child custody evaluations and those who have not conducted child custody evaluations also considered working the day shift as more helpful when the parent was described as a woman than when the parent was described as a man, and those who have not conducted child custody evaluations rated this as being much more helpful. These findings again suggest the potential for both groups to embody some bias toward the idea that women should be available to be their children’s primary caregiver and suggests perhaps that the bias of tender years doctrine is still affecting child custody decisions today [24].

Effects of Ethnicity of Parent

Those participant psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations and responded to the Black parent vignette weighed education more heavily than those who have conducted child custody evaluations and responded to the Black parent vignette. For these psychologists, the negative stereotypes of Black individuals may have contributed to their heavier weighting [25].

The results show that participant psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations rated the occupation of the Black parent as more helpful than it was for a White parent, and as more helpful for the Black parent than did those who have conducted child custody evaluations. This finding may be suggestive of a response to the negative stereotypes of Black men and women, such that when the Black parent is said to have an occupation, it rated as being helpful to their assessment [16,17,19]. However, the fact that this was only found for psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations may suggest that the specialized and ongoing training mental health professionals receive for child custody evaluations may be helpful in reducing this stereotypical bias.

Other Findings of Conducts v. Doesn’t Conduct Child Custody Evaluations

The results show that psychologists who conduct child custody evaluations weighted the history of the children hearing the verbal arguments significantly heavier than psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations. This is an interesting finding, as it may suggest that their specified training has taught them that this is an important factor to consider in the overall assessment, in particular, this may be a specific risk factor that is looked for in child custody evaluations. Psychologists who conduct child custody evaluations also rated the parent’s depression being in remission significantly heavier than participant psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations, again suggesting that this may be an important factor that, through training, they take into significant consideration for their assessment.

Interestingly, participant psychologists who do not conduct child custody evaluations weighted the parent’s occasional corporal punishment use more heavily than did the psychologists who have conducted child custody evaluations. While this may seem counterintuitive (wouldn’t psychologists who conduct evaluations weigh this particular area heavily if the decision of custody should be made in the best interest of the child?), this finding may suggest that child custody evaluators are able to make their decisions on the totality of a situation, rather than be focused on a specific negative factor. It may also suggest that what may be considered an important factor in a traditional therapeutic (i.e., mandated reporting) environment is not as important on its own in a child custody evaluation.

Gender of Psychologist

There were also several significant findings regarding the interaction of gender of the psychologists and whether or not they have conducted child custody evaluations. Male psychologists who have not conducted child custody evaluations weighed the parent being a day shift worker, the parent’s use of alcohol, the parent’s history of depression, and the history of verbal arguments heavier than any other combination of gender and having done child custody evaluations or not. These findings may suggest that male psychologists who have not gone through the specific training necessary to conduct child custody evaluations may be more susceptible to potential bias than their counterparts. Interestingly, male psychologists who have conducted child custody evaluations weighed the use of alcohol the least of any group. This again likely speaks to the fact that what may be an important factor in a traditional therapeutic environment, may not be as important on its own in a child custody evaluation.

Male Participant Psychologists and Ethnicity of Parent

A very interesting finding of this study is that the results show that male participant psychologists weighted the Black parent’s use of corporal punishment, alcohol use, receiving treatment for depression, and history of medication compliance significantly more heavily than did female psychologist participants.

Regarding alcohol use, these male psychologists rated the use of alcohol by the White parent as unimportant but weighted the Black parent’s alcohol use heavily. These particular characteristics align with the research regarding negative stereotypes of Black individuals [16, 18, 19, 20]. Such findings suggest that the male participant psychologists in particular may be susceptible to bias based on the stereotypes of Black individuals.

Effects of Parent’s Ethnicity and Mental Health

The results of this study suggest that receiving treatment for depression was weighted significantly more heavily when the parent was described as a Black than when the parent was described as White. However, the psychologist participants did not rate the parent receiving treatment for depression as differentially being helpful nor hurtful based on the ethnicity of the parent. The parent’s history of medication and treatment compliance was also weighted significantly more heavily when the parent was described as Black than when the parent was described as White, and parent’s history of medication and treatment compliance was also rated significantly more helpful when the parent was described as Black than when the parent was described as White. This was true for both male and female psychologist participants.

These findings, taken together, are both interesting and concerning. It appears as if, for Black parents, it is not whether or not they are receiving treatment for their mental health concerns that is important, but it is whether or not they are compliant with their therapeutic treatment and medication regimen that can help or hurt an evaluator’s perception of them. This aligns with Spector’s discussion regarding African Americans being more likely than Whites to be uncooperative, which, in turn, makes African Americans more likely to be restrained in inpatient settings [22].

The findings of the current study may be a result of this unconscious bias creeping into the participant’s perception of the Black parent’s ability to be compliant with their treatment; If Black parents are cooperative with their treatment, this is very helpful information to have – if they are not, it may negatively impact their overall evaluation. This is concerning, particularly because the aforementioned study is from 2001, and it is now twenty years later yet, it is possible that this particular unconscious bias still exists. Even more concerning is that this unconscious bias likely extends beyond just child custody evaluations, creeping into the mental health treatment of Black individuals in general. The idea that ongoing, negative perceptions of Black individuals a may ultimately affect their treatment and pathologizing their behavior even when this behavior should not be pathologized, as was discussed by Ashley [26].

Effects of Parent’s Gender and Mental Health

Receiving treatment for depression was weighted significantly more heavily when the parent was described as a Woman than when the parent was described as a Man, and parent’s history of medication and treatment compliance was also weighted significantly more heavily when the parent was described as a Woman than when the parent was described as a Man. While these factors were not found to be differentially more helpful nor hurtful based on the gender of the parent, it remains notable that such a difference was found.

Historically, there has been stigma surrounding women and mental illness, even when compared to men who are exhibiting the same symptoms [15]. Specific to child custody evaluations, women who are divorced are more likely to experience significantly higher daily stressors, need for more support, feelings of depression and conflict with their spouse than mothers who were in an intact family [7]. Thus, one may have surmised that these factors should actually have been rated as being more helpful. However, they were only weighted significantly more heavily by the participant psychologists. Perhaps representing an artifact of continued stigma regarding women and mental illness.

Clinical Implications

Given that the results appear to suggest that no one characteristic seems to have been weighted as important in isolation supports the idea that child custody evaluations should be comprehensive, and the whole of the situation and parent should be evaluated to make the most informed decision. This stresses the importance of graduate training programs placing an emphasis on conducting thorough Clinical Interviews prior to assessments, as well as teaching students to produce comprehensive and integrated assessment reports. This is not only relevant for those who will go on to conduct child custody evaluations in the future, but it is crucial for the administration and interpretation of assessments at large. It is also clear through the results of this study, that bias likely exists whether psychologists conduct child custody evaluations or not. However, it appears that those who conduct such evaluations may be less susceptible and/or more aware of their biases. Given the fact that the ability for an evaluator to remain objective and unbiased is rated as the most important factor for attorneys selecting an expert witness and that approximately 15% of judges feel as though this is not always the case, the results of this study suggest that child custody evaluators are likely receiving training that is reducing such bias [30].

Thus, it is crucial that not only child custody evaluators continue to receive diversity and sensitivity training, but the results suggest that every single practicing psychologist could greatly benefit from such training as well. Perhaps it would be beneficial to the field as a whole to necessitate a certain number of continuing education credits be dedicated to diversity training, particularly as the human experience is becoming more diverse with every generation.

Limitations and Direction for Future Research

There are several limitations to this study. The construction of the vignettes used in this study cannot accurately capture every aspect of what a psychologist may look for when doing an actual child custody evaluation. Certainly, asking a psychologist to make clinical judgements based on a condensed vignette and no other information is not best practice in the field, so it is entirely possible that the participant’s responses might not reflect how those factors would be weighted with more information and data available

Consequently, future research needs to utilize more complex and complete vignettes. Future research would be well-advised to expand upon the present study’s vignette approach to perhaps utilize a real child custody evaluation case, include assessment data, or, at the very least, include more background and contextual information. By including more robust information and/or data, more psychologist participants may feel comfortable generating a clinical opinion, and their clinical opinions may, at that point, provide more fruitful insight into potential biases.

Other limitations to this study include sample size, sampling procedure, and the location of the psychologists. Regarding sample size, it is clear that a very limited number of psychologist participants in this study have had experience conducting child custody evaluations. While the results of this study, particularly the results that include the responses of these nine individuals, certainly cannot be generalized to all psychologists who conduct child custody evaluations – the fact that some differences (i.e., potential biases) were found in the results should inform future research to make efforts to understand if these potential biases are present in a larger and more geographically-diverse sample.

Regarding the participants in this study, there is also a lack of diversity among those who participated and there were no participants who identified as Black. Additionally, the only reported genders were male or female. These factors illustrate a lack of diversity in the sample, which may ultimately affect the ability for generalization of the results, and not account for the perspective of marginalized, minority, and diverse populations. Future research should strive to address some of these limitations and continue to study the areas in which significant results were found. As, prior to this study, the effect of gender and racial bias in child custody evaluations had not been completed, the present study is meant to be built upon and to highlight the need for more research to be conducted to account for this gap in the literature.

Summary and Conclusions

Perhaps the most significant implication of the current study is that previous literature has yet to examine racial/ethnicity and gender bias in child custody evaluators. While the results are limited and preliminary, the current study has been able to contribute to filling that gap in the literature. The fact that the current study is quantitative rather than qualitative is also important to the field as it provides objective results rather than subjective accounts of areas of potential bias in child custody evaluators, providing a clearer picture of where future research into this area should head.

One thing that became apparent through recruitment efforts is that there is indeed a very small number of court-approved psychologists who conduct child custody evaluations in general. Therefore, the finding of a few significant differences between psychologist participants who have experience with child custody evaluations and those with no experience at all with child custody evaluations may indicate that further specialized training for those who conduct child custody evaluations is needed.

On the other hand, the fact that so few differences between these two groups were found may indicate that the basic training and education that all clinical psychologists are exposed to during their doctoral programs is clearly fundamental to the profession. Additionally, this also suggests that this core training serves well for those who go on to do child custody work.