Research Article

Research Article

Polyamory: A Study of Love Multiplied

Kelsey Gruebnau1*, Stephen E Berger2, Bina Parekh3 and Gilly Koritzky4

1Argosy University, Orange, California, United States

2The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Irvine, California United States

3The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Irvine, California United States

4The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Irvine, California United States

Kelsey Gruebnau, Argosy University, Orange, California, United States.

Received Date: November 24, 2020; Published Date: February 05, 2021

Abstract

This study was developed to gain a better understanding of the polyamorous population by sampling a group of self-identified polyamorous, or non-monogamous, adults. The dimensions investigated through this research included demographic data, polyamorous relationship type, perceived acceptance from others, relational and sexual satisfaction, and perceived access to quality mental healthcare services. The sample consisted of 1,005 polyamorous adults recruited through social media outlets and administered an online, self-report questionnaire. Information pertaining to demographics, polyamorous lifestyle, perceived discrimination, degree of disclosure, and attitudes toward mental healthcare services was gathered with the Polyamorous Lifestyle Scale, a measure developed by the principal researcher. Degrees of relational and sexual satisfaction were measured by the Global Measure of Relationship Satisfaction and the Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction, with permission from the author(s). Findings illustrated significant differences between individuals with differing polyamorous relationship types on degree of disclosure to others, perceived discrimination, comfort with disclosure to mental health professionals, relationship satisfaction, and sexual satisfaction. Differences were also found between self-identified gender on degree of sexual and relationship satisfaction. In addition, differences were found between individuals with differing sexual orientations on degree of sexual satisfaction. These findings demonstrate significant within-group differences among polyamorous individuals that appear to relate to relational and sexual satisfaction. Implications for clinicians working with this population, and how group membership, in addition to intersectionality, may impact the experiences of polyamorous individuals are provided. These findings are intended to inform future research and aid mental healthcare professionals in establishing evidenced-based practices and ethical guidelines for treatment and clinical training for working with polyamorous individuals. Overall, more in-depth research and training is needed on all aspects of polyamory, especially that which will promote the accessibility and development of quality mental healthcare services provided by clinicians attuned to the specific needs and experiences of this community.

Introduction

Polyamory is defined as a lifestyle in which an individual may have more than one concurrent romantic, sexual, or emotionally committed relationship, with the knowledge and consent of all parties involved [1]. The polyamorous relationship style emphasizes consciously choosing how many partners with whom one wishes to be involved, rather than abiding by social norms that dictate that committed romantic relationships may only exist between two people at any given time. The Polyamory Society [2] describes polyamory as the non-possessive, honest, responsible, and ethical philosophy and practice of loving multiple people simultaneously. Polyamory is considered to be an outgrowth of the term Polyfidelity, which was coined by the Kerista Group, a polyamorous commune based in San Francisco from the 1970s–1990s [3]. It is likely that polyamory existed, in one form or another, prior to the onset of the “sexual revolution,” but the available research credits the sexual revolution as an instance where enough individuals were engaging in polyamorous relationships publicly for the group to be recognized by mainstream society. The Kerista Group’s defined polyfidelity using the Greek translation of the word as meaning “faithful to many.” The group’s ideals included the creation of Citation: Kelsey Gruebnau, Stephen E Berger, Bina Parekh, Gilly Koritzky. Polyamory: A Study of Love Multiplied. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 4(2): 2021. OAJAP.MS.ID.000585. DOI: 10.33552/OAJAP.2021.04.000585. Page 2 of 17 an equitable sleeping schedule where partners rotated nightly. Group members were not permitted to engage in same-sex sexual encounters, however, this rule was not always observed [3]. Although the polyamorous community has changed and diversified a great deal since the Kerista Group, it is important to acknowledge the evolution of polyamory in order to better understand the individuals who belong to the community today.

Past research and public opinion seem to imply that polyamory is inherently linked with the LGBTQ+ community, despite demographic data that illustrates a different picture. In a sample of one thousand polyamorous individuals, 51% identified as bisexual, 44% as heterosexual, and 4% as gay/lesbian [4]. While the LGBTQ+ community has a public reputation of experimenting with nonmonogamous relationships, research shows that heterosexual couples have also experimented with non-monogamous practices such as “swinging” and open marriages for many years [5]. In 2000, Nichols & Shernoff [6] reported that there has been a surge of interest in non-monogamy in recent years among people of all sexual orientations and identities. The extent to which polyamorous behavior is exhibited in the population at large is unknown, including many of the details about the individuals subsumed within the polyamorous relationship style and community.

Educational resources on alternative relationship structures report that individuals in the poly community find joy in having close relationships on both sexual and emotional planes with multiple partners [7]. Polyamory can provide opportunities for personal growth that come from close associations with new and diverse individuals. Reported benefits include household cooperation, shared responsibilities, aide with child rearing, and dispersion of financial obligations. In addition, polyamorous individuals may experience increased personal freedom with the potential for sexual exploration in a non-judgmental environment. Other beneficial effects reported by individuals within the community include strengthening of spousal bonds, increased self-awareness, and a feeling of belonging that is often present in a healthy polyamorous relationship [7]. One of the most significant relational strengths prevalent among polyamorous groups is that individuals report gaining significant practice with communicating needs and negotiating “arrangements” that are satisfactory to all involved parties. The polyamorous community prioritizes “sex positivity,” a practice in which there is acceptance of a variety of forms of sexual sharing and identities, leading to sense of heightened selfactualization, individuation, and differentiation [8,9].

An unfortunate byproduct of the lack of training clinicians receive on the specific needs of the polyamorous community and the very limited literature that exists is that there seems to be few clinical resources adequately equipped to meet this population’s needs. There exists a perception within the polyamorous community that mental health clinicians are not well informed about poly lifestyles nor adept at understanding the needs of polyamorous individuals [10]. This perception may limit the extent to which polyamorous individuals feel they have access to quality mental health services and lead to a reluctance in seeking services.

Early research conducted on the social and psychological functioning of poly individuals in comparison to general population norms found no significant difference between groups [10,11]. Comparisons have been performed on levels of neuroticism, maturity, promiscuity, happiness, adjustment, pathology, and feelings of sexual adequacy, the results of which showed no discernible difference. Overall, it is accepted that members of sexual minority groups seek psychotherapy services for the same reasons as their mainstream counterparts [6]. The conclusion that can be derived from these preliminary findings is that no mental health issues have been found to impact the polyamorous community differently than the general population, but polyamorous individuals may be less likely to seek mental health services for fear of ridicule, bias or potential recommendations to alter their preferred lifestyle.

Since little is known about the polyamorous community among the general public or in the field of research, mental health professionals may not understand the underlying emotions, perceptions, or experiences of the group. In order to provide effective and ethical care to polyamorous individuals, it is essential to learn more about their community and those who comprise that community. Prejudicial views tend to develop and thrive when there is minimal information available about a group of people, therefore, it is essential to find more information about the views, lifestyles, and demographics of the polyamorous community in order to better serve polyamorous individuals with greater sensitivity and understanding.

Methods

Participants

The present study utilized quantitative data collected from polyamorous/non-monogamous self-identifying adults (N=1,005) to better understand the polyamorous community. Participants were recruited using both a purposive and snowball sampling technique. The participants were recruited online, necessitating access to a computer, or mobile device, and an internet connection. All participants were required to indicate that they were over the age of 18 (age range: 18 – 61 years, Mage = 30.6 years), prior to participation in the study. For the purpose of this research, “polyamory” is operationally defined a preference for the practice, or state, of having more than one concurrent romantic, sexual, and/or emotional relationship at a time, with the knowledge and consent of all involved. Participants were recruited regardless of their current relationship status, gender identity, sexual orientation, or other demographic variables, apart from their self-identified preference for polyamorous relationships.

A link to the digital survey was made available via a variety of social media platforms (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit), websites, and forums. The survey link was provided along with a brief description of the survey, which accommodated any site- or moderator-specific posting requirements. In addition, a general invitation for the survey link to be shared via social media was communicated, to facilitate the snowball sampling method. Upon accessing the survey URL, potential participants were directed to the informed consent document, which included information about the purpose of the study, time requirements, risks/benefits of participation, contact information, and what participation in the study would entail. It was then requested that electronic consent to voluntarily participate in the study be provided and that all participants attest that they had read the informed consent document and were at least 18 years old at the time of survey access.

While the target sample of this study was polyamorous individuals, no restrictions were placed on access to the survey URL to limit access to non-polyamorous individual. Instead, an exclusion question was asked regarding each participant’s preferred relationship structure and non-polyamorous identifying participants were immediately directed to the Debriefing Statement, the Comments/Feedback Form, and the Raffle Entry Form. Only respondents who completed the survey in its entirety were included in the sample. For this study, survey completion is defined as someone who provided scorable responses to at least 75% of the questions presented to them. The number of items presented to each participant was variable due to “conditional branching,” a technique used to create custom pathways through a questionnaire that varies based upon a participant’s response. Conditional branching, a programming instruction that directs the participant to another part of the survey based upon their response to a particular question, was employed when participants were asked about their country of origin and current relationship status. The final polyamorous sample consisted of 1,005 participants.

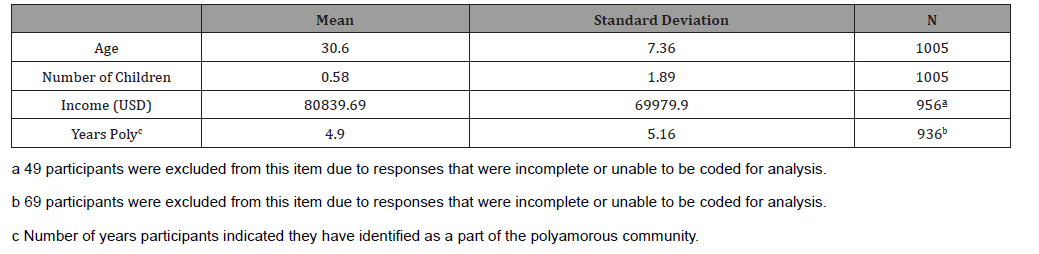

The following Tables present the participants’ demographic information. Table 1 illustrates the quantitative demographic variables collected; namely, age, yearly household income (USD), and number of years as a part of the polyamorous community. It can be seen from Table 1 that the mean age of participants was 30.60 years old. The mean number of years participants identified as being a part of the polyamorous community, at the time of survey completion, was 4.9 years.

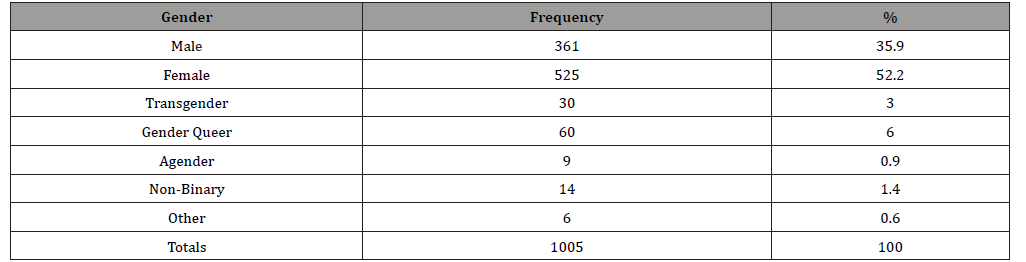

Table 2 illustrates the gender identification categories of the sample, in addition to the number of participants in each group and the percentage that number represents of the total sample. It can be seen in Table 2 that 35.9% of the sample identified as male, 52.2% of the sample identified as female, and 11.9% of the sample identified as transgender, gender queer, agender, non-binary, or other. The number of participants in each gender identification category was taken into consideration when making comparisons between groups.

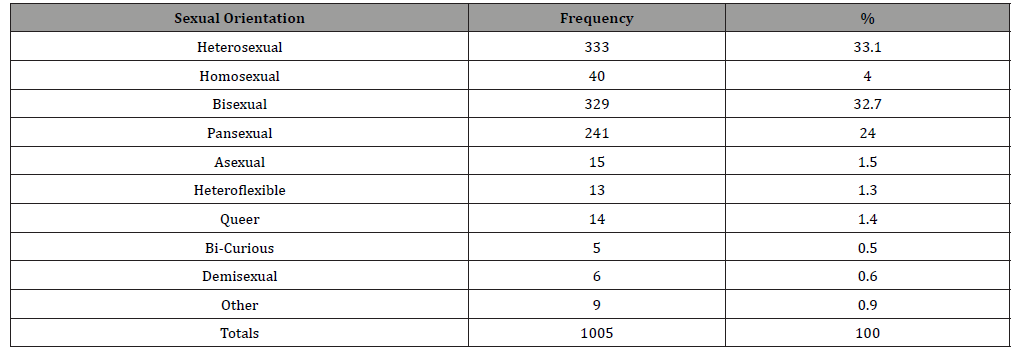

Table 3 illustrates the sexual orientation identification categories of the sample, in addition to the number of participants in each group and the percentage that number represents of the total sample. It can be seen in Table 3 that 33.1% of the sample identified as heterosexual, 32.7% identified as bisexual, 24% identified as pansexual, and 10.2% of the sample identifies as homosexual, asexual, heteroflexible, queer, bi-curious, demisexual, or other. Again, the number of participants in each group was taken into consideration when between group differences were analyzed.

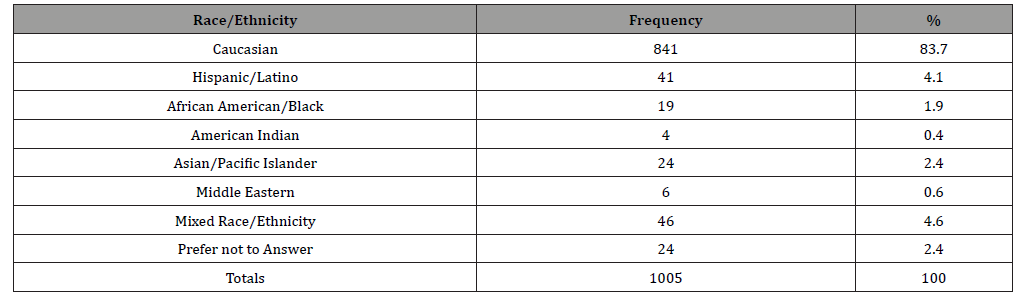

Table 4 shows the racial identification categories of the sample, in addition to the number of participants in each group and the percentage that each group represents of the polyamorous sample. It can be seen in Table 4 that 83.7% of the sample identified as Caucasian, while 4.6% identified as Mixed Race/Ethnicity, 4.1% as Hispanic/Latino, 2.4% as Asian/Pacific Islander, 1.9% as African American/Black, and 3.4% identified as either American Indian, Middle Eastern, or indicated that they preferred not to answer the racial identification question.

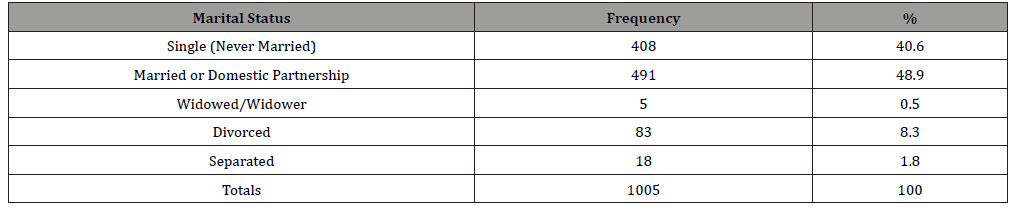

Table 5 illustrates the marital status of the sample, in addition to the number of participants in each group and the percentage that each group represents of the polyamorous sample. It can be seen in Table 5 that 48.9% of the sample indicated that they are Married or in a Domestic Partnership, while 40.6% of the sample identified as Single (Never Married). In addition, 8.3% of the sample indicated that they are Divorced, 1.8% as Separated and 0.5% identified as Widowed/Widower.

Measures

Polyamory lifestyle questionnaire: A questionnaire was created by the researcher for this study as a means to gather information regarding the attitudes, practices, preferences, and demographic data of polyamorous individuals. The Polyamorous Lifestyle Questionnaire [PLS] consists of 32 items including three inclusion criteria questions, twelve general demographic questions, three poly-specific demographic questions, two questions regarding safe sex practices, and twelve Likert-type questions. The PLS asked participants to indicate their age, gender, sexual orientation, race/ ethnicity, marital status, number of children, level of education, employment status, yearly income, country of residence, geographic region, community type, current relationship type, ideal relationship type, number of years as a member of the polyamorous community, and safe sex practices. In addition, participants were asked to respond to Likert-type questions about jealousy, disclosure of their relationship preferences, discrimination, and attitudes toward seeking mental health services. The PLS questionnaire was first used as a part of this study; therefore, the reliability and validity of the items and overall questionnaire are unknown. The PLS was solely intended for the purpose of gathering data as a part of exploratory research with individuals belonging to the polyamorous community.

Table 1:Descriptive Statistics of Quantitative Variables.

Table 2:Gender Identity of the Polyamorous Sample.

Table 3:Sexual Orientation of the Polyamorous Sample.

Table 4:Race/Ethnicity of the Polyamorous Sample.

Table 5:Marital Status of the Polyamorous Sample.

The global measure of relationship satisfaction: The Global Measure of Relationship Satisfaction [GMREL] was used to measure the participants’ overall relationship satisfaction [12]. The five items in the GMREL are each identified by the authors as separate dimensions. The GMREL items are normally scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale but were scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale for this study. For each item, respondents were asked to rate their level of satisfaction by marking a response on the scale denoting their relationship as: Good-Bad, Pleasant-Unpleasant, Positive-Negative, Satisfying-Unsatisfying, and Valuable-Worthless. The possible total scores on the GMREL ranged from 5 – 25 points. The responses for each dimension were summed, higher scores indicating a greater relationship satisfaction than lower scores. The reliability and validity of these scales are reported below along with the reliability and validity for the next measure that was used.

The global measure of sexual satisfaction: The Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction [GMSEX] was used to measure the participants’ overall sexual satisfaction [12]. As with the GMREL, the five dimensions of the GMSEX are normally scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale but were scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale for this study. For each item, respondents were asked to rate their level of satisfaction by marking a response on a scale denoting their sex life as: Good-Bad, Pleasant-Unpleasant, Positive-Negative, Satisfying-Unsatisfying, and Valuable-Worthless. The possible total scores on the GMSEX ranged from 5 – 25 points. The responses for each dimension were summed, higher scores denoting greater sexual satisfaction than lower scores.

The GMREL and GMSEX have demonstrated a high internal consistency reliability, ranging from .91 to .96 and .90 to .96 respectively, when studied on a sample of married or cohabitating respondents in heterosexual relationships, married respondents in China, and women from sexual-minorities [13-17]. Two investigations found the test-retest reliability of the assessment measures to be high: .81 at 2 weeks, .70 at 3 months, and .61 at 18 months for the GMREL and .84 at 2 weeks, .78 at 3 months, and .73 at 18 months for the GMSEX [15,18].

The construct validity for the GMREL was supported by a significant correlation (r=69, p<.001) with the Dyadic Adjustment Scale [19], while the construct validity for the GMSEX was supported by a significant correlation (r=-.65, p<.001) with the Index of Sexual Satisfaction [ISS] [20]. Research has shown that the GMREL is significantly correlated with the GMSEX and that high summed scores on the GMREL are associated with high summed scores on the GMSEX and vice versa [13]. In addition, it has been found that the GMREL and GMSEX are associated with other measures of relationship and sexual satisfaction, including sexual communication, sexual desire, sexual cognitions, sexual esteem, sexual frequency, and communality [16,21,22].

Procedures

Participants who acknowledged their consent to participate in the study by selecting “agree” at the bottom of the Informed Consent document were then advanced to the next page of the survey. Participants’ ongoing consent was also documented via their willingness to complete the survey in its entirety. After providing consent, participants were asked to disclose their romantic relationship preference to ensure that they belonged to the target sample. Participants who did not meet the inclusion criteria were immediately directed to the Debriefing Statement, Comments/ Feedback Form, and the Raffle Entry Form. All other participants were directed to the Polyamory Lifestyle Questionnaire, The Global Measure of Relationship Satisfaction, and The Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction in that order. The PLS, GMSEX, and GMREL took approximately 10 minutes to complete. The participants were then directed to the Debriefing Statement and, finally, the optional Raffle Entry Form.

All of the information gathered through the course of this study was collected anonymously, with no identifying information requested. The response profiles of each individual participant were categorized with the use of identifications numbers assigned by the survey host site. The data is stored, by the primary researcher, on a password protected computer and will only be accessible by the researcher and the researcher’s supervising Chair for three years. Following the three-year data retention time, the data will be destroyed. Participants who request a summary of the study results and recommendations, following completion of the project, will be provided with information by the primary researcher.

For participation in the study, participants were given the option to enter into a raffle for a $50 gift card, as a token of appreciation. To participate in the raffle, participants were required to provide a valid e-mail address. Participants were reminded raffle entry was completely voluntary and would not violate the confidentiality of survey responses. Following collection of the Raffle Entry Form data, each entry was assigned a random numerical value and a random number generator was utilized to select the winning entry.

Results

The statistical analyses for this study were conducted using IBM SPSS software. The intention of this study was to examine the demographic data, relationship identification, relational disclosure and discrimination, relational/sexual satisfaction, and attitudes toward mental health services as reported by the sample of polyamorous individuals. Descriptive statistics were analyzed for all demographic variables and relationship variables, including relationship/sexual satisfaction and attitudes toward mental health services. Therefore, Multivariate Analyses of Variance (MANOVA) were conducted to examine difference between: 1) current relationship type and level of disclosure among friends, family, and at work, 2) current relationship type and perceived level of discrimination among friends, family, at work, and mental health professionals, 3) current relationship type and reported attitudes toward mental health professionals, 4) current relationship type and relationship satisfaction as measured by the GMREL, 5) current relationship type and sexual satisfaction as measured by the GMSEX, 6) gender and sexual satisfaction as measured by the GMSEX, 7) gender and relationship satisfaction as measured by the GMREL, 8) sexual orientation and relationship satisfaction as measured by the GMREL, 9) sexual orientation and sexual satisfaction as measured by the GMSEX. Additional ANOVAs and pairwise comparisons were conducted to further investigate statistically significant findings. The results of those analyses are presented next in the afore mentioned order.

Differences between current relationship type and level of disclosure among friends, family, and at work

Comparisons between current relationship type (monogamy, hierarchical non-monogamy, non-hierarchical non-monogamy, swinging, triad, polyfidelity, polyfamily, tribe/pod, non-committed non-monogamy, “other”, none, and “undecided”) on level of disclosure to friends, family, and at work were examined using a MANOVA. Multivariate tests were conducted and found that there was a significant difference between current relationship types on a linear combination of disclosure to friends, disclosure to family, and disclosure at work (Wilks’ Lambda=0.82; F(11, 3003)=6.05, p=0.00). Follow-up univariate ANOVAs found that there was a significant difference between current relationship types in level of disclosure to friends (F(11,993)=12.06, p=0.000), family (F(11,993)=10.68, p=0.00), and at work (F(11,993)=5.06, p=0.00). To identify which relationship types differed from which other relationship types, pairwise comparisons were conducted (Tukey HSD).

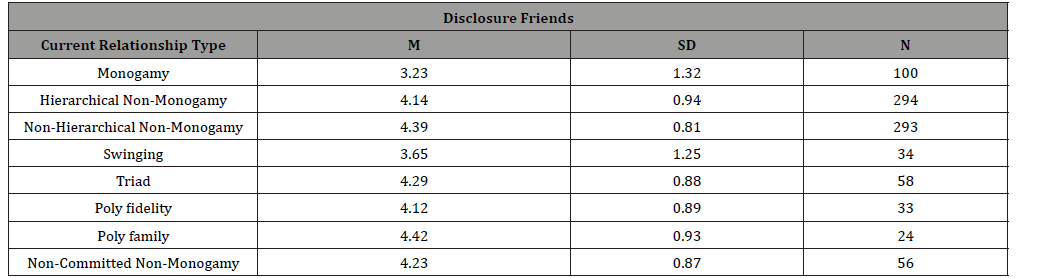

As can be seen in Table 6, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals currently in monogamous relationships disclose their polyamorous relationship preferences to friends less than polyamorous individuals in hierarchically non-monogamous (p=0.00), non-hierarchically non-monogamous (p=0.00), triad (p=0.00), polyfidelity (p=0.00), polyfamily (p=0.00), non-committed non-monogamous (p=0.00), and “other” relationships (p=0.01). In addition, it was found that polyamorous individuals currently in non-hierarchical non-monogamous relationships disclose their polyamorous relationship preferences to friends more than polyamorous individual in swinging relationships (p=0.00).

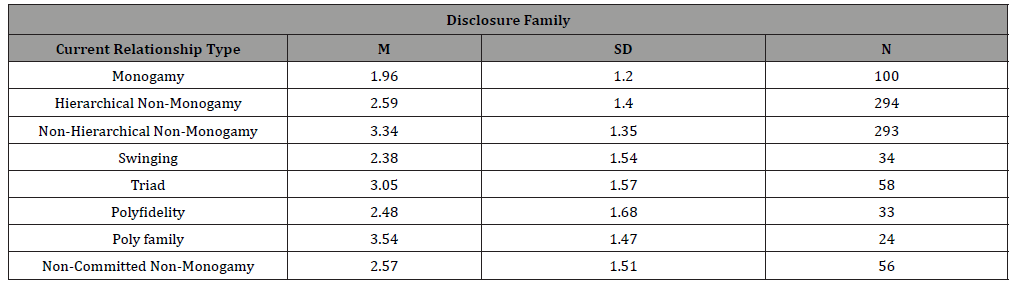

As can be seen in Table 7, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals currently in monogamous relationships disclose their polyamorous relationship preferences to family less than polyamorous individuals in hierarchically non-monogamous (p=0.01), non-hierarchically non-monogamous (p=0.00), triad (p=0.00), and polyfamily relationships (p=0.00). In addition, it was found that polyamorous individuals currently in non-hierarchical non-monogamous relationships disclose their polyamorous relationship preferences to family more than polyamorous individuals in hierarchical non-monogamous (p=0.00), swinging (p=0.01), polyfidelity (p=0.05), and non-committed nonmonogamous relationships (p=0.01).

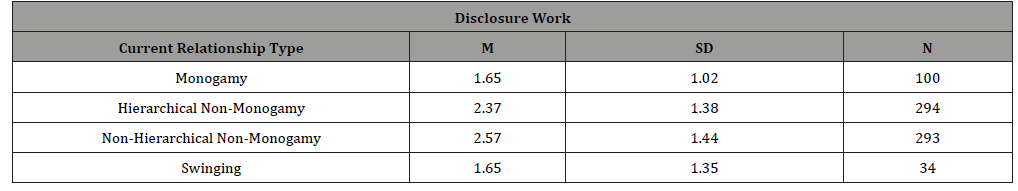

As can be seen in Table 8, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals currently in monogamous relationships disclosed their polyamorous relationship preferences at work less than polyamorous individuals in hierarchically non-monogamous (p=0.00) and non-hierarchically non-monogamous relationships (p=0.00). Finally, it was found that polyamorous individuals currently in non-hierarchical non-monogamous relationships disclose their polyamorous relationship preferences at work more than polyamorous individuals in swinging relationships (p=0.02).

Table 6:Means and Standard Deviations of the Polyamorous Sample Based on Current Relationship Type and Level of Disclosure to Friends.

Table 7:Means and Standard Deviations of the Polyamorous Sample Based on Current Relationship Type and Level of Disclosure to Family.

Table 8:Means and Standard Deviations of the Polyamorous Sample Based on Current Relationship Type and Level of Disclosure at Work.

Differences between current relationship type and level of perceived discrimination among friends, family, at work, and with health care professionals

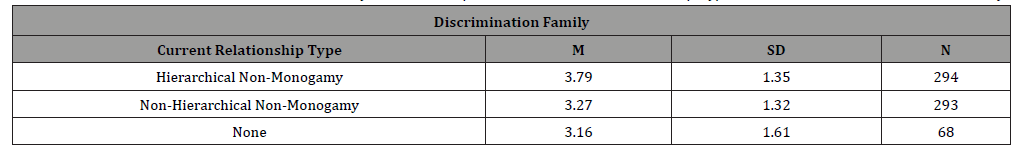

Comparisons between current relationship type on level of perceived discrimination from friends, family, and at work were examined using a MANOVA. Multivariate tests were conducted and found that there was a significant difference between current relationship types on a linear combination of perceived discrimination from friends, family, and at work (Wilks’ Lambda=0.93; F(11,4008)=1.56, p=0.01). Follow-up univariate ANOVAs found that there was a significant difference between current relationship types in level of perceived discrimination from friends (F(11,993)=2.42, p=0.01) and family (F(11,993)=2.59, p=0.00), but not at work or among health care professionals. To identify which relationship types differed from which other relationship types, pairwise comparisons were conducted (Tukey HSD).

As can be seen in Table 9, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals currently in hierarchical nonmonogamous relationships perceive more discrimination from family than polyamorous individuals in non-hierarchical nonmonogamous relationships (p=0.00) and polyamorous individuals who selected “none” when asked about their current relationship status (p=0.04). When pairwise comparisons were performed between current relationship types on discrimination from friends, no significant differences were found between groups.

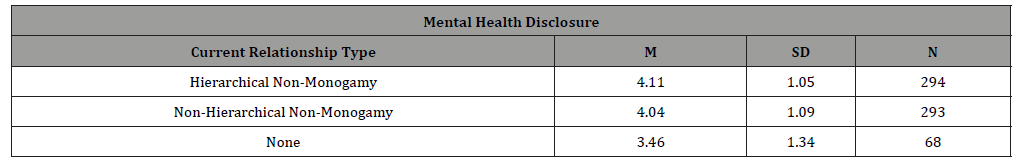

Differences between current relationship type and attitudes toward mental health professionals

Comparisons between current relationship type on attitudes toward mental health professionals were examined using a MANOVA. Multivariate tests were conducted and found that there was a significant difference between current relationship types on a linear combination of comfort with disclosure to mental health professionals, perceived acceptance from mental health professionals, and perceived lifestyle discouragement from mental health professionals (Wilks’ Lambda=0.95; F(11,3003)=1.47, p=0.04). Follow-up univariate ANOVAs found that there was only a significant difference between current relationship types on comfort with disclosure to mental health professionals (F(11,993)=2.46, p=0.00). To identify which relationship types differed from which other relationship types, pairwise comparisons were conducted (Tukey HSD).

As can be seen in Table 10, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals currently in hierarchical nonmonogamous relationships reported more comfortability disclosing their polyamorous relationship preferences to mental health professionals than polyamorous individuals who selected “none” when asked about their current relationship status (p=0.00). In addition, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals currently in non-hierarchical non-monogamous relationships reported more comfortability disclosing their polyamorous relationship preferences to mental health professionals than polyamorous individuals who selected “none” when asked about their current relationship status (p=0.00).

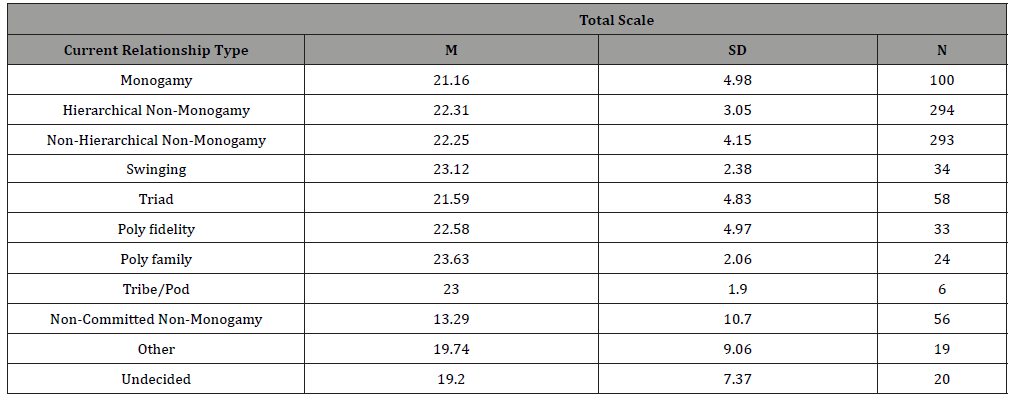

Difference between current relationship type and relationship satisfaction as measured by the GMREL

Comparisons between current relationship type on relationship satisfaction were examined using a MANOVA. Multivariate tests were conducted and found that there was a significant difference between current relationship types on a linear combination of the dimensions of relationship satisfaction and overall relationship satisfaction as measured by the GMREL (Wilks’ Lambda=0.38; F(11,6018)=19.62, p=0.00). Follow-up univariate ANOVAs found that there was a significant difference between current relationship types on overall relationship satisfaction (F(11,993)=132.32, p=0.00) as measured by the GMREL total scale score. To identify which relationship types differed from which other relationship types, pairwise comparisons were conducted (Tukey HSD).

Table 9:Means and Standard Deviations of the Polyamorous Sample Based on Current Relationship Type and Level of Discrimination from Family.

Table 10:Means and Standard Deviations of the Polyamorous Sample Based on Current Relationship Type and Level of Comfort with Disclosure to Mental Health Professionals.

As can be seen in Table 11, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals currently in non-committed nonmonogamous relationships reported lower overall relationship satisfaction (as measured by the GMREL total scale score) than polyamorous individuals in monogamous relationships (p=0.00), hierarchical non-monogamous relationships (p=0.00), nonhierarchical non-monogamous relationships (p=0.00), swinging relationships (p=0.00), triad relationships (p=0.00), polyfidelity relationships (p=0.00), polyfamily relationships (p=0.00), tribe/ pod relationships (p=0.00), “other” relationships (p=0.00), and polyamorous individuals who reported that they were “undecided” regarding their current relationship type (p=0.00).

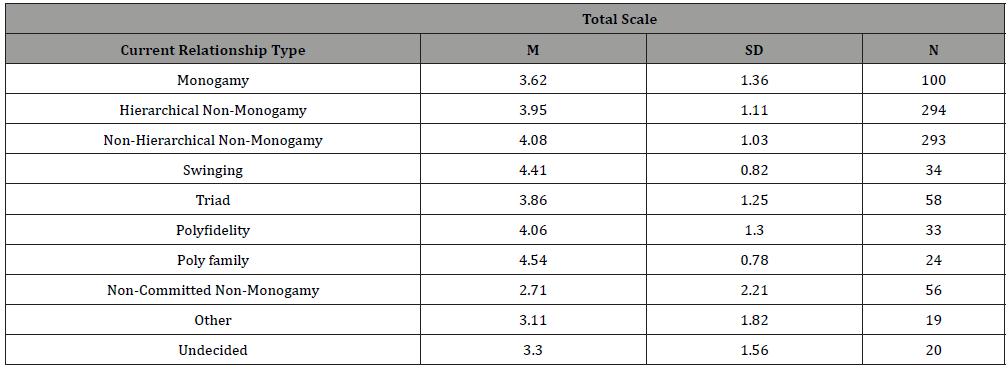

Difference between current relationship type and sexual satisfaction as measured by the GMSEX

Comparisons between current relationship type on sexual satisfaction were examined using a MANOVA. Multivariate tests were conducted and found that there was a significant difference between current relationship types on a linear combination of dimensions of sexual satisfaction and overall sexual satisfaction as measured by the GMSEX (Wilks’ Lambda=0.47; F(11,6018)=14.69, p=0.00). Follow-up univariate ANOVAs found that there was a significant difference between current relationship type on all dimensions of the GMSEX: Dimension 1 (F(11,993)=65.95, p=0.00), Dimension 2 (F(11,993)=85.33, p=0.00), Dimension 3 (F(11,993)=81.08, p=0.00), Dimension 4 (F(11,993)=63.21, p=0.00), Dimension 5 (F(11,993)=,78.77 p=0.00), and the total scale score, overall relationship satisfaction (F(11,993)=86.13, p=0.00). To identify which relationship types differed from which other relationship types, pairwise comparisons were conducted (Tukey HSD).

As can be seen in Table 12, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals currently in non-committed nonmonogamous relationships reported that their current sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 1 on the GMSEX) than polyamorous individuals in monogamous (p=0.00), hierarchical non-monogamous (p=0.00), non-hierarchical non-monogamous (p=0.00), swinging (p=0.00), triad (p=0.00), polyfidelity (p=0.00), and polyfamily relationships (p=0.00). Pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals currently in monogamous relationships reported their current relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 1 on the GMSEX) than polyamorous individuals in swinging (p=0.05) and polyfamily relationships(p=0.04). Pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals currently in “other” identified relationships reported their sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 1 on the GMSEX) than polyamorous individuals in non-hierarchical non-monogamous (p=0.03), swinging (p=0.01), and polyfamily relationships (p=0.01). In addition, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals who identified as “undecided” regarding their current relationship type reported that their sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 1 on the GMSEX) than polyamorous individuals in swinging relationships (p=0.05).

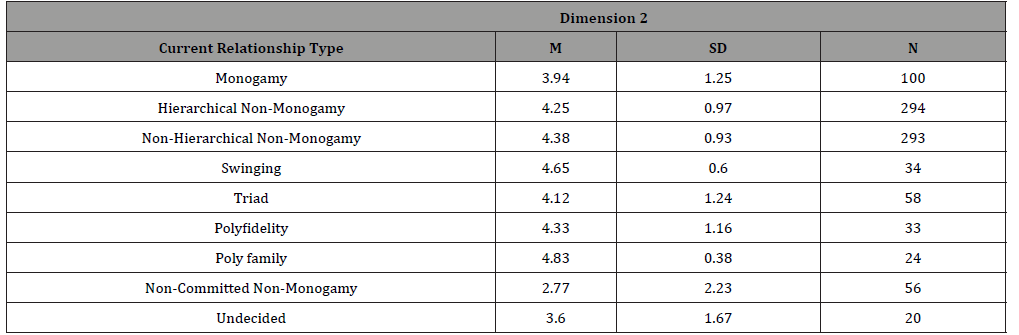

As can be seen in Table 13, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals in non-committed non-monogamous relationships reported that their current sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 2 on the GMSEX) than polyamorous individuals in monogamous (p=0.00), hierarchical non-monogamous (p=0.00), non-hierarchical non-monogamous (p=0.00), swinging (p=0.00), triad (p=0.00), polyfidelity (p=0.00), and polyfamily relationships (p=0.00). Pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals currently in monogamous relationships reported their sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 2 on the GMSEX) than polyamorous individuals in non-hierarchical non-monogamous (p=0.04) and polyfamily relationships (p=0.03). In addition, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals who identified as “undecided” in their current relationship type reported that their sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 2 on the GMSEX) than polyamorous individuals in swinging (p=0.05) and polyfamily relationships (p=0.02).

Table 11:Means and Standard Deviations of Overall Relationship Satisfaction (GMREL) by Current Relationship Type.

Table 12:Means and Standard Deviations of Sexual Satisfaction (GMSEX Dimension 1) by Current Relationship Type.

Table 13:Means and Standard Deviations of Sexual Satisfaction (GMSEX Dimension 2) by Current Relationship Type.

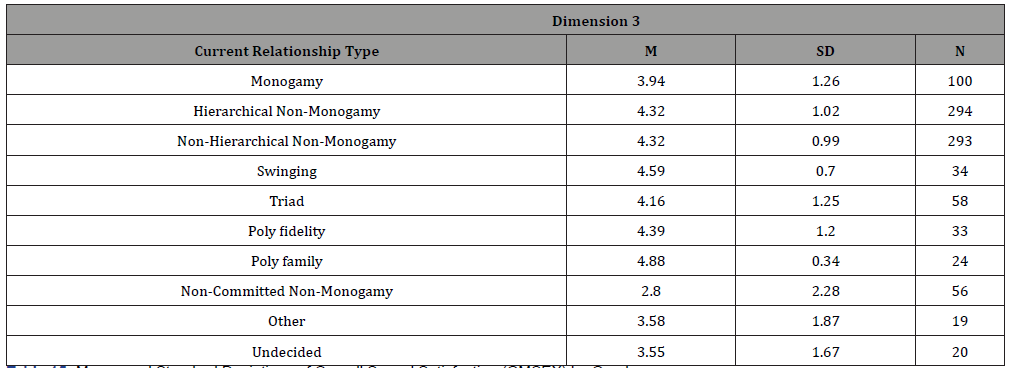

As can be seen in Table 14, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals in non-committed non-monogamous relationships reported that their current sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 3 on the GMSEX) than polyamorous individuals in monogamous (p=0.00), hierarchical non-monogamous (p=0.00), non-hierarchical non-monogamous (p=0.00), swinging (p=0.00), triad (p=0.00), polyfidelity (p=0.00), and polyfamily relationships (p=0.00). Pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals in monogamous relationships reported that their current sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 3 on the GMSEX) than polyamorous individuals in polyfamily relationships (p=0.02). In addition, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals in polyfamily relationships reported that their current sexual relationships were more satisfying (as measured by Dimension 3 on the GMSEX) than polyamorous individuals in “other” relationships (p=0.02) and polyamorous individuals who identified as “undecided” in their current relationships type (p=0.01).

Difference between genders and sexual satisfaction as measured by the GMSEX

Comparisons between gender (male, female, transgender, gender queer, agender, non-binary, other) on sexual satisfaction were examined using a MANOVA. Multivariate tests were conducted and found that there was a significant difference between gender on a linear combination of dimensions of sexual satisfaction and overall sexual satisfaction as measured by the GMSEX (Wilks’ Lambda=0.94; F (6,6023) =1.99, p=0.00). Follow-up univariate ANOVAs found that there was a significant difference between gender on overall sexual satisfaction (F (6,998) =4.27, p=0.00), as measured by the GMSEX total scale score. To identify which gender identifications differed from one another, pairwise comparisons were conducted (Tukey HSD).

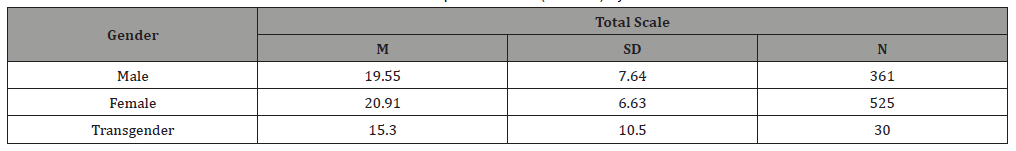

As can be seen in Table 15, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals who self-identified as transgender reported that their current sexual relationships were less satisfying overall, as measured by the GMSEX total scale score, than polyamorous individuals who identified as male (p=0.03) and female (p=0.00).

Table 14:Means and Standard Deviations of Sexual Satisfaction (GMSEX Dimension 3) by Current Relationship Type.

Table 15:Means and Standard Deviations of Overall Sexual Satisfaction (GMSEX) by Gender.

Table 16:Means and Standard Deviations of Overall Relationship Satisfaction (GMREL) by Gender.

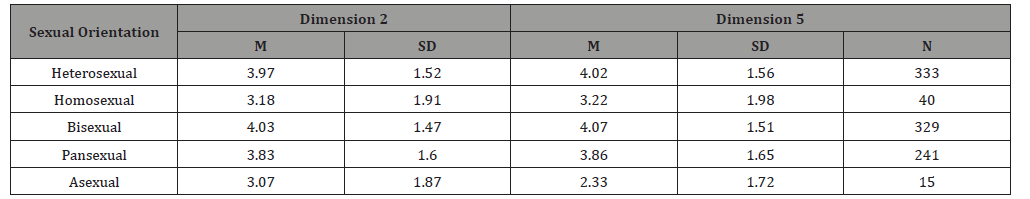

Table 17:Means and Standard Deviations of Sexual Satisfaction (GMSEX Dimension 2 & 5) by Sexual Orientation.

Difference between genders and relationship satisfaction as measured by the GMREL

Comparisons between self-identified gender on relationship satisfaction were examined using a MANOVA. Multivariate tests were conducted and found that there was a significant difference between gender on a linear combination of dimensions of relationship satisfaction and overall relationship satisfaction, as measured by the GMREL (Wilks’ Lambda=0.95; F (6,6023) =1.82, p=0.00). Follow-up univariate ANOVAs found that there was a significant difference between self-identified gender on overall sexual satisfaction (F (6,998) =4.06, p=0.00), as measured by the GMREL total scale score. To identify which genders differed from one another, pairwise comparisons were conducted (Tukey HSD).

As can be seen in Table 16, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals who identified as transgender reported that their current relationships were less satisfying overall, as measured by the GMREL total scale score, than polyamorous individuals who identified as male (p=0.04) and female (p=0.00).

Difference between sexual orientations and relationship satisfaction as measured by the GMREL

Comparisons between sexual orientation (heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, pansexual, asexual, heteroflexible, queer, bi-curious, demisexual, other) on relationship satisfaction were examined using a MANOVA. Multivariate tests were conducted and found that there was not a significant difference between sexual orientations on a linear combination of dimensions of relationship satisfaction and overall relationship satisfaction as measured by the GMREL (Wilks’ Lambda=0.95; F (9,6020) =1.14, p=0.25). However, follow-up univariate ANOVAs found that there was a significant difference between sexual orientation on Dimension 1 of the GMREL (F (9,995) =1.98, p=0.04). The means and standard deviations were used to conduct pairwise comparisons (Tukey HSD), which failed to identify statistical significance between any of the sexual orientation groups.

Difference between sexual orientations and sexual satisfaction as measured by the GMSEX

Comparisons between sexual orientation on sexual satisfaction were examined using a MANOVA. Multivariate tests were conducted and found that there was a significant difference between sexual orientations on a linear combination of dimensions of sexual satisfaction and overall sexual satisfaction as measured by the GMSEX (Wilks’ Lambda=0.92; F (9,6020) =1.78, p=0.00). Followup univariate ANOVAs found that there was a significant difference between sexual orientations on all dimensions of the GMSEX: Dimension 1 (F (9,995) =2.06, p=0.03), Dimension 2 (F (9,995) =3.13, p=0.00), Dimension 3 (F (9,995) =2.20, p=0.02), Dimension 4 (F (9,995) =2.06, p=0.03), Dimension 5 (F (9,995) =3.90, p=0.00), and the total scale score, overall sexual satisfaction (F (9,6021) =2.76, p=0.00). To identify which sexual orientation group differed from which other sexual orientation group, pairwise comparisons were conducted (Tukey HSD).

As can be seen in Table 17, pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals who identified as bisexual reported that their sexual relationships were more satisfying (as measured by Dimension 2 on the GMSEX) than polyamorous individuals who identified as homosexual (p=0.04). Pairwise comparisons found that polyamorous individuals who identified as asexual reported that their sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 5 on the GMSEX) than polyamorous individuals who identified as heterosexual (p=0.00), bisexual (p=0.00), and pansexual (p=0.01).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to quantitatively examine a sample of polyamorous individuals to better understand these individuals, their relationships, and attitudes toward mental health services. All this was done with the goal of educating mental health clinicians on how they may better serve polyamorous individuals, create safer treatment environments, and ultimately informing the development of evidence-based practices. Dimensions of interest included demographic data, with special attention paid to gender differences, sexual orientation, and polyamorous relationship types. In addition, relationship and sexual satisfaction scales were administered, as well as questions regarding level of discrimination and disclosure across settings, and experiences with mental health professionals. The following section will discuss significant findings relevant to the various polyamorous relationship types of participants and how significant differences were found between groups on level of disclosure, discrimination, attitudes toward mental health professionals, relational satisfaction, and sexual satisfaction. In addition, the differences between gender identities and sexual orientations of the sample are discussed regarding relational and sexual satisfaction.

Polyamorous relationship types and the polyamorous lifestyle scale

Differences between relationship types on level of disclosure: Lifestyle Scale (PLS) was intended to pinpoint the polyamorous community’s level of disclosure to their friends, family, and at work. The findings from this portion of the PLS demonstrated a significant difference between polyamorous relationship types (monogamy, hierarchical non-monogamy, non-hierarchical non monogamy, swinging, triad, polyfidelity, polyfamily, tribe/pod, noncommitted non-monogamy, “other”, none, and “undecided”) and their level of disclosure across settings.

It was found that polyamorous individuals who are currently in monogamous relationships have disclosed their polyamorous relationship preferences significantly less to friends than those in hierarchical, non-hierarchical, triad, polyfidelity, polyfamily, noncommitted, and “other” polyamorous relationships. In addition, it was found that those in monogamous relationships disclosed their poly relationship preferences significant less to family members than those in hierarchical, non-hierarchical, triad, and polyfamily relationships. Polyamorous individuals currently in monogamous relationships also disclosed their poly relationship preferences less at work than their hierarchical and non-hierarchical peers. These findings seem somewhat intuitive, in that polyamorous individuals who are currently engaged in monogamy may not be at a stage in their polyamorous identity development that they would feel comfortable openly discussing their relationship preferences with others, especially those outside of the polyamorous community. These individuals may be in a state of transition from monogamy to polyamory or they may have yet to disclose their interest in polyamory to their monogamous partners. It is also possible that these individuals are influenced by other factors that both keep them from disclosing their relationship preferences and from currently engaging in polyamory. For example, living in a community where being non-monogamous may cause them to be ostracized, put them in danger of losing their job and support system, or even at risk of physical harm.

Additionally, it was found that polyamorous individuals presently in non-hierarchical non-monogamous relationships were more likely to disclose their polyamorous relationship preferences to friends, family, and at work than individuals engaged in swinging. Matsick et. al. [23], opined that the relational dynamics of individuals who identify as swingers may be more sex-centric when it comes to connections with other partners, which was also referred to by Bergstrand & Williams [24], as engaging in ‘emotional monogamy,’ as opposed to focusing on the emotional components on their extra-dyadic relationships. This emphasis on the sexual component of ethically non-monogamous relationships may lead to individuals who identify as swingers to keep their extra-dyadic relationship private and limit the necessity or perceived appropriateness of disclosure to friends, family, and coworkers.

Finally, it was found that non-hierarchical polyamorous individuals were more likely to disclose their polyamorous relationship preferences to family than those engaged in hierarchical polyamory, polyfidelity, and non-committed non-monogamy. It is unclear why non-hierarchical polyamorous individuals are significantly more likely to disclose their poly relationship preferences to family than these other groups. This may be an area that requires further analysis, or a finding influenced by another variable unknown to the researcher.

Differences between relationship types on level of perceived discrimination: Another aspect of the PLS was intended to measure the polyamorous community’s experience of discrimination among friends, family, at work, and with health care professionals. The findings from this portion of the PLS demonstrated a significant difference between polyamorous relationship types and their experience of discrimination among family. No significant differences were found between groups on discrimination among friends, at work, or with health care professionals.

It was found that polyamorous individuals in hierarchical relationships reported that they experience a significantly higher level of discrimination from family members than those in nonhierarchical relationships and polyamorous individuals who responded “none” when asked about their current relationship status. It is unclear why this difference exists, but one supposition may be that a polyamorous family member who is not currently in a relationship or in non-hierarchical relationships may be able to “pass” as someone who hasn’t “settled down” yet (i.e. someone who is still ultimately looking for a monogamous relationship). In contrast, a poly family member who is in a hierarchical relationship (i.e. currently has a committed romantic partner), while actively seeking other romantic relationships may make it more difficult for family members with traditional views on relationships to remain dismissive of the individual’s lifestyle.

Differences between relationship types on attitudes toward mental health: Again, one of the primary aims of this study was to better understand the polyamorous community’s interactions with mental health services and clinicians, in the hopes that this information would help inform how future evidencedbased practices are employed when working with the polyamorous community. To elucidate how polyamorous individuals currently feel about seeking mental health services, a portion of the PLS posited questions about the participants’ perceptions of the availability of mental health services. These questions pertained to comfort with relationship preference disclosure to mental health professionals, relational acceptance from mental health professionals, and relationship preference discouragement from mental health professionals.

The findings illustrated that there was only a significant difference between current relationship types on comfortability with disclosing polyamorous relationship preferences to mental health professionals. It was found that individuals currently in hierarchical and non-hierarchical relationships were significantly more comfortable disclosing their poly lifestyles to mental health professionals than polyamorous individuals who selected “none” when asked about their current relationship status. As can be seen in Table 8, all of the groups have a mean greater than three, which indicates that when asked to respond to the statement, “If I sought mental health services, I would feel comfortable disclosing my nonmonogamous relationship preferences to a therapist,” the mean response was between “neither agree nor disagree” and “agree.” This data is heartening in that it suggests neutrality and often there is some comfortability with disclosures to therapists, when the poly relationship type groups are viewed as a whole.

Again, this finding seems somewhat intuitive, in that individuals who are not currently in romantic relationships may not feel the need to disclose that they are polyamorous to mental health professionals, while someone actively engaged in polyamory may find it more necessary as a means to genuinely interact with the clinician. Also, people who indicated that they were not in romantic relationships may be new to the polyamorous lifestyle, recently out of a polyamorous or monogamous relationship, or in some other transitory state that may impact their level of comfort with having an open conversation regarding their polyamorous relationship identification. As indicated before, poly individuals may not be currently in a polyamorous relationship by choice or circumstantially due to where they live, their social circle, or other variables that could confound the relationship between current relationship type and comfort with disclosure to mental health professionals.

Polyamorous relationship types and relational/sexual satisfaction

Differences between relationship types on the GMREL: Relationship satisfaction was a variable of interest in this study because it holds implications for both general, societal acceptance and mental health services when it comes to the validation and understanding of polyamorous relationships. An obvious question that arises when a non-traditional relationship structure is discussed is how happy, or satisfied, the members of that group are within their respective relationships. For the purpose of assessing relational satisfaction among polyamorous individuals, the Global Measure of Relationship Satisfaction was employed. The GMREL is a 5-item scale utilized to assess an individual’s overall relationship satisfaction. The individual items and total scale score of the GMREL were used to assess the differences between polyamorous relationship types on relationship satisfaction.

On the GMREL, Polyamorous individuals in non-committed non-monogamous relationships reported that their relationships were significantly less satisfying overall than all other polyamorous individuals currently in relationships. Interestingly, this finding seems to imply that the commitment aspect of polyamorous relationships plays an important role in relational satisfaction. It is unclear whether there is some unique trait attributed to individuals in non-committed polyamorous relationships that leads to lower relationship satisfaction or if these individuals’ relationship satisfaction scores would go up should they participate in a committed relationship.

In addition, it was found that polyamorous individuals in hierarchical relationships reported that their relationships were significantly more satisfying (as measured by Dimension 5 on the GMREL) than those who reported that they were “undecided” regarding the nature of their current relationships. This finding may seem somewhat obvious in that the hierarchical/primarysecondary relationship structure implies some inherent preference for, or value of, the individual’s primary partner. In addition, those who identified as “undecided” may be in a transitional phase within their relationship(s) or polyamorous identify, or their indecision regarding their relationship structure may reflect an ambivalence toward their current partner.

Differences between relationship types on the GMSEX: Sexual satisfaction was another variable of interest in this study due to the large amount of stigma and myths that exist in public opinion regarding the sexual proclivities of non-monogamous individuals. It is important to note that the researcher’s purpose in including this analysis in this study was not to overemphasis the role of sex in the polyamorous lifestyle, but simply to investigate the sexual satisfaction of polyamorous individuals as one possible facet of this multidimensional relationship orientation. For the purpose of assessing sexual satisfaction among polyamorous individuals, the Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction was employed. The GMSEX is a 5-item scale utilized to assess an individual’s sexual satisfaction. The individual items and total scale score of the GMSEX were used to assess the differences between polyamorous relationship types on sexual satisfaction.

On the GMSEX, polyamorous individuals in non-committed relationships reported that their sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimensions 1, 2, and 3 on the GMSEX) than those is monogamous, hierarchical, non-hierarchical, swinging, triad, polyfidelity, and polyfamily relationships. Polyamorous individuals who identified their relationship type as “other” reported that their sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 1 on the GMSEX) than those in nonhierarchical, swinging, and polyfamily relationships. Individuals who indicated that they were undecided regarding their current relationship type reported that their sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 1 on the GMSEX) than those in swinging relationships. Polyamorous individuals in polyfamily relationships reported that their sexual relationships were more satisfying (as measured by Dimension 3 on the GMSEX) than those who categorized themselves as “other” or “undecided” in their current relationship type.

Polyamorous individuals currently in monogamous relationships reported that their sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 1 on the GMSEX) than those in swinging and polyfamily relationships. Monogamous individuals also reported that their sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 4 on the GMSEX) than those in nonhierarchical and polyfamily relationships. Monogamous individuals reported that their sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 3 on the GMSEX) than those in polyfamily relationships.

The results of these analyses were extremely complex and did not seem to proffer any insight in the reason behind the sexual satisfaction of the various relationship types. It is possible that this finding is significant but may require additional analysis or research to understand the relationships among these variables. Future research will want to include measures that could provide insight into factors affecting these feelings.

Sexual orientation and relational/sexual satisfaction Differences between sexual orientations on the GMREL: Although there must be a clear distinction made between sexual orientation and relationship orientation as a facet of an individual’s identity, investigating any intersectionality that may exist between these two factors is important as a means to inform clinical practice and a greater depth of understanding of the poly community. The polyamorous sample was asked a demographic question regarding their sexual orientation, and these groups were then compared by the responses on the GMREL to assess for any between group differences on relationship satisfaction.

Analyses were run to identify any significant differences between the sexual orientations of the polyamorous individuals sampled and relationship satisfaction, as measured by the GMREL. Although it was found that there was a significant difference between groups on Dimension 1 of the GMREL, further analyses were unable to identify any statistical significance between specific groups. No significance was found between groups on the GMREL total scale score.

Differences between sexual orientations on the GMSEX: Analyses were also run to identify any significant differences between the sexual orientations of the polyamorous individuals sampled and sexual satisfaction, as measured by the GMSEX. It was found that polyamorous individuals who identified as bisexual reported that their sexual relationships were more satisfying (as measured by Dimension 2 on the GMSEX) than those who identified as homosexual. In addition, polyamorous individuals who identified as asexual reported that their sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 5 on the GMSEX) than those who identified as heterosexual. No significance was found between groups on the GMSEX total scale score.

Gender and relational/sexual satisfaction

Differences between genders on the GMREL: Analyses were run to identify any significant difference between self-identified gender of the polyamorous individuals sampled and relationship satisfaction, as measured by the GMREL. It was found that the polyamorous individuals who identified as transgender reported that their relationships were less satisfying overall than individuals who identified as female. In addition, polyamorous individual who identified as transgender also reported that their relationships were less satisfying overall than individuals who identified as male. It is unclear whether this difference in relational satisfaction is due to the individuals’ identification as transgender alone or if there is an interaction between the identification of transgender and polyamorous that impacts the lower scores on the GMREL.

Differences between genders on the GMSEX: The GMSEX was utilized to assess any differences between self-identified gender of the polyamorous individuals sampled and sexual satisfaction. It was found that polyamorous individuals who identified as transgender reported that their sexual relationships were less satisfying overall than individuals who identified as female. Individuals who identified as transgender also reported that their sexual relationships were less satisfying overall than individuals who identified as male. In addition, Poly individuals who identified as transgender reported that their sexual relationships were less satisfying (as measured by Dimension 4 on the GMSEX) than those who identified as gender queer. Finally, polyamorous individuals who identified as female reported that their relationships were more satisfying (as measured by Dimension 4 on the GMSEX) than those who identified as male.

As with the GMREL, it is unclear whether the lower GMSEX sexual satisfaction scores are related to the individuals’ identification as transgender or if there is an important interaction or confounding variable at work that has caused these individuals to score lower on the GMSEX. Additional research would be necessary to better understand the relationship between the gender of polyamorous individuals and sexual satisfaction.

Clinical implications

The clinical implications of this study may be an increased understanding of the polyamorous community and the needs of this community that necessitate specific training of mental health clinicians. In addition, this information can help erode stereotypes with accurate information regarding this population on issues such as the clinical “pathologizing” of the polyamory relationship style. There is a high degree of bias expressed toward polyamorous relationships and the individuals within them [25]; this norm is pervasive and has remained largely unchallenged for years [26,27]. The normative social ideals of monogamy find their way into how clinicians measure psychological constructs such as attachment, love, trust, and satisfaction, which deeply impacts the ability of the polyamorous individuals to receive unbiased, appropriate psychological services [25]. This both inhibits clinicians from being able to work appropriately with the polyamorous community and creates an environment where polyamorous individuals are unable to be assured of the quality of mental health services they can receive.

While this study barely scratches the surface of the experiences of polyamorous individuals and how they may be impacted by the type of clinical care currently available, it is clear that polyamorous individuals are still open to seeking mental health services. In addition, it is also apparent that mental health care professionals are not currently equipped with adequate, if any, training in treating polyamorous patients. This is evidenced by the paucity of research on polyamory and the complete lack of evidence-based practices established for working with this community. As with any minority group, the onus of responsibility for establishing appropriate treatment methodology lies with practitioners and researchers within the field. This study serves to illustrate the necessity of a call-to-action among the mental health community to rectify the fact that there are no guidelines for the treatment and assessment of polyamorous patients, let alone standards for population-specific interventions.

It is this researcher’s opinion that when interacting with polyamorous patients, a clinician who does not have specialized training in working with the population should do everything possible to remain open, reserve judgement, and listen to what the patient’s presenting concern is instead of focusing on a curiosity regarding their lifestyle. It is highly recommended that clinicians seek supervision and/or consultation regarding their work with polyamorous patients so that any countertransference or other issues related to clinical competency and the therapeutic relationship can be addressed. Overall, conceptualizing a patient’s polyamorous lifestyle from a family and systems therapy perspective may help clinicians reframe the experiences of this community in a way that is more easily understood in the scope of available research and training. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it is crucial that all clinicians who find themselves in a position to serve this community take an active role in educating themselves about polyamorous culture and experiences so that the patient is not forced into the role of teacher, when they themselves are seeking support. If after taking time to educate themselves on polyamorous culture, a clinician feels their own lack of knowledge or biases impact their ability to appropriately provide services to the patient, referral to another mental health professional is recommended.

Limitations and directions for future research

There are several limitations to the current study, which include both sampling and instrumental limitations which may impact the generalizability of this research.

Sampling limitations: One limitation to the current study is the nature of self-selected survey participants, individuals who chose to participate in the study may have had various motivations that could have consequently impacted the results of the study. This self-selection bias is important because there may be a portion of the polyamorous population that is disinterested in participating in research, and whose responses would be meaningfully different from those who chose to participate in this study.

Another limitation to the current investigation is the purposive, snowball sampling method that was utilized. The survey was distributed to various websites and forums reportedly frequented by members of the polyamorous community, in addition to general social media outlets. Although the purpose of the survey was to collect data from a wide range of participants, the online format and availability of the survey may have limited the generalizability of the results to all facets of the polyamorous population because access to the online survey was limited to participants who had means (i.e. a computer or mobile phone), access (via the internet and social media accounts), and computer literacy. Future research should include non-internet-based recruitment methods that strive to sample individuals who may not have access to computers or may be less likely to participate in online surveys.

Instrumental limitations: The instruments used were all selfreport measures with high face-validity, which may have enabled participants to anticipate the investigator’s desired responses. Therefore, future research should include a measure less vulnerable to social desirability responding to help rule out such contamination and/or to include an assessment of the individual’s tendency to respond in a socially desirable manner.

Conclusion

The results of this study illustrated many unique facets of the polyamorous community, such as demographic composition, differences in level of disclosure to specific other people in their lives, attitudes toward mental health professionals, experiences of discrimination, and relational/sexual satisfaction. It was found that polyamorous-identifying individuals currently in monogamous relationships were less likely to disclose their polyamorous identity to others than many of the other relationship type subgroups. In addition, individuals in hierarchical and non-hierarchical relationships were more likely to feel comfortable discussing their poly lifestyle with mental health professionals than individuals who were not currently in a romantic relationship. It was also found that polyamorous individuals in non-committed non-monogamous relationships, and those who identified as transgender, report experiencing a lower level of relational and sexual satisfaction than many of their peers.

The results of this study are of note because they illustrate opportunities for future research and instances where mental health care services may be of use to the polyamorous individuals outside of the normal scope of practice. For example, the discrepancy in level of disclosure to others between polyamorous individuals currently in monogamous relationships and their peers may be due to a developmental paradigm that can occur during the process of polyamorous identify formation. In addition, the level of comfortability in disclosing polyamorous relationship preferences to mental health professionals seems to be impacted by current relationship status; therefore, it may be important to find out what is causing this lack of comfortability among polyamorous individuals not currently in relationships and isolate any that originate from the treating clinician. Individuals in non-committed non-monogamous relationships reported lower relational and sexual satisfaction than many of their peers. This finding may also demonstrate a part of the polyamorous identify formation process, or a cluster of traits that are unique to this subgroup. Finally, the relational and sexual satisfaction scores of transgender-identifying polyamorous individuals present an opportunity to better understand the topic of intersectional polyamory, and how mental health clinicians might better serve minority subgroups within the polyamorous community.

Gaining a wealth of demographic data, knowledge of different relational styles within the community, stigmatization faced by polyamorous individuals, issues related to mental health services, along with other pertinent information about the community, will hopefully aid in the development of a new, more accurate understanding of this community clinically and overall. It is hoped that this project will serve as a psychoeducational tool in training current and future clinicians in their ability to appropriately serve this community. Appropriate training methods may include, but are not limited to, incorporation of the concept of relationship type as a diversity variable to be taught in post-secondary education, continuing education units presented on the topic of working with polyamorous clients, and competency evaluations through the use of case conceptualizations, roleplays, or clinical supervision.

Additionally, an ideal outcome would be for this research to act as a steppingstone for the development of future research and treatment techniques that may be used to ensure ethical and effective mental health care of polyamorous individuals. The American Psychological Association [28], clearly spells out the guidelines for clinical practice with LGBT patients, and while they do not directly apply to the polyamorous community, they may act as an exemplar for the type of guidelines that must be established in the aim of standardized practice for the treatment of polyamorous patients. The objective and ultimately, the obligation of clinicians is to provide a safe environment where patients can seek services without fear of discrimination and with the assurance that services will be provided to them by a clinician who is able to competently work within the ethical guidelines of their profession. Beyond the overarching principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence, clinicians must strive to understand the unique experiences and challenges faced by polyamorous individuals, the effects of stigma on this community, how intersectionality may impact polyamorous patients, and the effect of the clinician’s own attitudes and knowledge on the therapeutic relationship. These components are a necessary foundation for establishing effective clinical interventions and evidence-based practices when working with the polyamorous community.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- Weitzman G (2004) The identity development of bisexual and polyamorous individuals.

- Polyamory Society (1997–2015).

- Sheff E (2015) The polyamorists next door: Inside multiple-partner relationships and families. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Weber A (2002) Survey Results: Who are we? And other interesting impressions. Loving More 30: 4-6.

- Serina AT, Hall M, Ciambrone D, Phua VC (2013) Swinging around stigma: Gendered marketing of swingers’ websites. Sexuality & Culture 17(2): 348-359.

- Nichols M, Shernoff M (2000) Therapy with sexual minorities. Principles and practice of sex therapy 4: 353-367.

- Ramey JW (1975) Intimate groups and networks: Frequent consequence of sexually open marriage. Family Coordinator 515-530.

- Kassoff E (1989) Nonmonogamy in the lesbian community. Women & Therapy 8(1-2): 167-182.

- Weitzman G, Davidson J, Phillips RA, Fleckenstein JR, Morotti Meeker C (2009) What psychology professionals should know about polyamory. The National Coalition for Sexual Freedom.

- Knapp JJ (1976) An exploratory study of seventeen sexually open marriages. Journal of Sex Research 12(3): 206-219.

- Rubin AM (1982) Sexually open versus sexually exclusive marriage: A comparison of dyadic adjustment. Alternative Lifestyles 5(2): 101-108.

- Lawrance KA, Byers ES, Cohen JN (1998) Interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction questionnaire. Sexuality-related measures: A compendium. 2: 525-530.

- Cohen JN (2008) Minority stress, resilience, and sexual functioning in sexual-minority women. University of New Brunswick, Canada.

- Lawrance KA, Byers ES (1992) Development of the interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction in long term relationships. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 1(3): 123-128.

- Lawrance KA, Byers ES (1995) Sexual satisfaction in long‐term heterosexual relationships: The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Personal Relationships 2(4): 267-285.

- Peck SR, Shaffer DR, Williamson GM (2005) Sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction in dating couples: The contributions of relationship communality and favorability of sexual exchange. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality 16(4): 17-37.

- Renaud CA, Byers ES, Pan S (1997) Sexual and relationship satisfaction in mainland China. Journal of Sex Research 34(4): 399-410.

- Byers ES, MacNeil S (2006) Further validation of the interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. J Sex Marital Ther 32(1): 53-69.

- Spanier GB (1976) Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family 15-28.

- Hudson WW, Harrison DF, Crosscup PC (1981) A short‐form scale to measure sexual discord in dyadic relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 17(2): 157-174.

- Mac Neil S, Byers ES (2009) Role of sexual self-disclosure in the sexual satisfaction of long-term heterosexual couples. Journal of Sex Research 46(1): 3-14.

- Renaud CA, Byers ES (2001) Positive and negative sexual cognitions: Subjective experience and relationships to sexual adjustment. Journal of Sex Research 38(3): 252-262.

- Matsick JL, Conley TD, Ziegler A, Moors AC, Rubin JD (2014) Love and sex: polyamorous relationships are perceived more favourably than swinging and open relationships. Psychology & Sexuality 5(4): 339-348.

- Bergstrand C, Williams J (2000) Today’s alternative marriage styles: The case of swingers. Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality 3: 10.

- Conley TD, Ziegler A, Moors AC, Matsick JL, Valentine B (2013) A critical examination of popular assumptions about the benefits and outcomes of monogamous relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review 17(2): 124-141.

- Ley DJ (2009) Insatiable wives: Women who stray and the men who love them. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Sheff E (2010) Strategies in polyamorous parenting. Understanding non-monogamies. New York, Routledge, 169-181.

- American Psychological Association (2012) Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. The American Psychologist 67(1): 10-42.

-

Kelsey Gruebnau, Stephen E Berger, Bina Parekh, Gilly Koritzky. Polyamory: A Study of Love Multiplied. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 4(2): 2021. OAJAP.MS.ID.000585.

Global Measure of Relationship Satisfaction, sexual orientations on sexual satisfaction, polyamorous population, Kerista Group, sexual revolution, psychotherapy services, emotions, perceptions, Is operationally, Caucasian

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.