Research Article

Research Article

Perceptual Accuracy and Thought Complexity of a Correctional Population with the Wechsler IQ Test and the Rorschach

Alberto Miranda1*, Stephen E Berger2, Bina Parekh2 and Ashley Ginter3

1Cultural Neuropsychology Program-Hispanic Neuropsychiatric Center of Excellence, UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, USA

2Department of Psychology, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Irvine, USA

3Federal Bureau of Prisons, USA

Alberto Miranda, Cultural Neuropsychology Program- Hispanic Neuropsychiatric Center of Excellence, UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, USA.

Received Date: January 01, 2020; Published Date: January 17, 2020

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the differences between incarcerated and non-incarcerated individuals on the cognitive measures of the Rorschach Inkblot Test (i.e., FQ-%, FQo%, FQu%, WD-%, Complexity, F%, WSumCog, TP-Comp, and EII-3) to help determine how the two groups process information. In addition, it involved an investigation of performance on the Rorschach variables among different levels of intellectual and perceptual ability as determined by the WAIS-IV to understand how the variables relate to underlying cognitive processes. The study involved the use of archival data from 36 incarcerated males and 43 males receiving community mental health services. Several multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) were used to determine whether differences existed between the two groups, as well as between different levels of intellectual and perceptual ability for each of the specified Rorschach variables. Findings demonstrated differences in Complexity and WSumCog scores among levels of intellectual ability, suggesting more effective processing and synthesis of information with advanced cognitive ability. Differences among perceptual ability levels were found in Complexity, WSumCog, F%, and EII-3 scores. Differences between incarcerated and non-incarcerated individuals were not significant, suggesting Rorschach variables may be less influenced by external factors such as quality of education. Nevertheless, important qualitative distinctions specific to offender cognitive style were identified, which led to recommendations regarding treatment interventions, including the incorporation of cognitive rehabilitation models. Differences within the incarcerated sample based on the level of care needed by the inmate were found for Complexity, F%, WSumCog, EII-3, and TP-Comp, demonstrating a relationship between perceptual dysfunction and adaptability within the correctional environment. Finally, an interaction effect was found between intellectual ability and incarceration status on FQu%, suggesting a preference for more conventional responses with increasing levels of cognitive ability. Future investigations are recommended to consider specific factors involved in the experience of incarceration that may help to explain this relationship.

Introduction

The United States maintains the world’s largest population of prisoners [1]. According to Carson, “U.S. state and federal correctional facilities held an estimated 1,574,700 prisoners on December 31, 2013, an increase of 4,300 prisoners from yearend 2012” [2]. Recidivism rates in the United States are also among the highest. Results of a 2002 study showed that among the 275,000 prisoners released in 1994, 67.5% were rearrested within 3 years, 51.8% of whom were serving prison terms [3]. Additionally, minority groups account for a major portion of the prison population in the United States. In 2009, African Americans represented 39.4% of the prison and jail population while Hispanics represented 20.6% [4]. Taken together, these statistics encompass the continued need for research geared toward the development of assessment measures to improve rehabilitation and psychological treatment programs for the prison population in the United States.

One important component of rehabilitation may involve the cognitive functioning of prisoners. Studies have demonstrated a significant number of prisoners within secure forensic settings exhibit cognitive difficulties related to problematic thinking styles. Lindsay, Hastings, Griffiths, and Hayes, for instance, found a significant number of offenders in their study had an intellectual disability (IQ < 70) or were within the borderline range (IQ between 70 and 79) of intellectual functioning [5]. Similarly, Sinclair, Blencowe, McCaig, and Misch found prisoners tend to have significantly lower mean scores on the Full Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ) and Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV) than the general population [6,7]. Prisoners in that study also demonstrated greater neuropsychological deficits in behavioral inhibition, cognitive flexibility, and problem-solving [6]. Such difficulties are likely to underlie problem behaviors or cognitive distortions that result in criminal activity or other issues that affect social functioning. Understanding the relationship between cognitive deficits and criminal behavior thus has important implications for the conceptualization and rehabilitation of offenders.

have significantly lower mean scores on the Full Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ) and Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV) than the general population [6,7]. Prisoners in that study also demonstrated greater neuropsychological deficits in behavioral inhibition, cognitive flexibility, and problem-solving [6]. Such difficulties are likely to underlie problem behaviors or cognitive distortions that result in criminal activity or other issues that affect social functioning. Understanding the relationship between cognitive deficits and criminal behavior thus has important implications for the conceptualization and rehabilitation of offenders.

While the association between low intellectual functioning and criminal activity has long been demonstrated, standard neuropsychological measures have limitations in specifically assessing the prison population. Intellectual measures like the WAIS-IV are often insensitive to demographic variables such as ethnicity and educational attainment [11,12]. Lower scores may be representative of factors such as low socioeconomic status and poor quality of educational experience rather than true cognitive deficits. This is likely to result in the misclassification of many prisoners based on their perceived level of intellectual ability. Important aspects of cognitive functioning that pertain to treatment may also be overshadowed by the low base rates of the prison population. For this reason, additional measures and techniques, such as performance-based measures, may be necessary to supplement the assessment of prisoners to ensure greater accuracy.

Perceptual reasoning is one important aspect of cognition that plays a critical role in problem-solving. Perceptual reasoning is generally considered to be less affected by educational experience when compared to verbal comprehension tasks [13]. Measures that assess components of perceptual ability (i.e., accuracy and complexity) may therefore offer critical information about the cognitive ability of disadvantaged populations, such as offenders. The Rorschach is a behavioral problem-solving task in which respondents must use reasoning and problem-solving skills to make sense of the perceptual regularities and irregularities found in inkblots. In creating a response to the ambiguous and complex stimuli, respondents must utilize their internal cognitions and underlying schema. According to Perry, Viglione, and Braff, this makes the Rorschach a good technique for assessing thought disorder, psychological complexity when problem-solving, and interpersonal understanding of human representations [14].

The Rorschach includes several scales that incorporate cognitive functional abilities. The complexity scale from the Rorschach Performance Assessment System (R-PAS), for instance, provides information regarding a person’s cognitive capacity for problem-solving and organizing his or her environment. Responses that integrate different locations and have multiple descriptive variables result in higher complexity scores. The form quality scale represents adaptive functioning in how the individual interprets or organizes external stimuli from the environment. In a sense, this scale allows researchers to examine how an individual organizes ambiguous information into some type of order. Creating some type of order when information is random and disparate is important for successful problem-solving. According to Frank, form quality may also reflect an individual’s “capacity for better functioning in the world” [15]. Together, these scales may provide a key interpretation of the functioning of a person in his or her environment, as well as the ability to approach a situation that is unfamiliar, organize it, and respond cohesively. In this manner, performance-based measures, such as the Rorschach, tap into crucial components of cognitive style, or rather the preferred way in which an individual processes information.

Statement of the Problem

Current cognitive assessment of the prison population is hindered by a variety of factors, including test bias of intellectual measures, subcultural components of the prison environment that influence performance, and the underrepresentation of prisoner normative data on the standard measures used. The Rorschach, however, may offer a unique opportunity to enhance the assessment of intellectual and cognitive ability specific to the prison population. Contemporary intelligence tests appear to be better indicators of socioeconomic status and education, thus giving clinicians information on the limitations or relative cognitive strengths of their patients. These measures, however, do not provide a window into how a subject processes stimulus. The Rorschach demonstrates where the perceptual processing problems are located and indicates how faulty processing may lead to problematic thinking and judgment. In other words, intelligence tests indicate the result of cognitive processes whereas the Rorschach demonstrates the underlying cognitive processes that (in combination with other factors such as education and socioeconomic status) result in the IQ test scores a person ultimately obtains. Thus, the Rorschach may potentially give unique information to provide better intervention strategies and treatment that will address patients’ specific needs, because focus can be brought to specific cognitive processes that need to be modified if people are to make better intellectual analyses and decisions. However, limited empirical support, especially in relation to the prison population, exists to support this claim. While perceptual accuracy appears to play an important role in the development and maintenance of cognitive distortions, it remains unclear as to how perceptual problems specifically relate to social functioning and criminal behavior.

While the prison population and recidivism rates remain high, it is necessary to understand how problems with social and cognitive functioning may result in criminal behavior for some individuals. The present study was designed to address two specific goals. The first was to uncover how intellectual ability relates to performance within the cognitive domains of the Rorschach (i.e., perceptual accuracy, thought complexity, and thought disturbance). The second goal was to investigate how perceptual inaccuracy relates to problems with social functioning or criminal behavior. The current study was guided by a quantitative design in which the researcher examined archival data from two assessment sites. In doing so, the researcher compared the intellectual functioning, perceptual accuracy, thought complexity, and thought disturbance of adult male prisoners from a California prison for men to those of an adult male sample from an outpatient clinic. Each participant previously had been administered a neuropsychological battery that included the WAIS-IV, Rorschach (using the R-PAS scoring method), and the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI) or the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2). These measures were used separately to determine overall intellectual abilities (WAIS-IV FSIQ, VCI, PRI, WMI, PSI), perceptual reasoning (WAIS-IV PRI), perceptual accuracy (R-PAS FQo%, FQu%, FQ-%, WD-%), perceptual complexity (R-PAS Complexity and F%), and thought disturbance (R-PAS WSumCog, TP-Comp, EII-3).

This study offers several important implications for clinical practice. Determining whether the Rorschach cognitive variables correlated with other neuropsychological measures was designed to support its utility to enhance the understanding of a patient’s cognitive style. As measures such as the WAIS-IV may be limited in terms of assessing certain populations, the Rorschach may help to correctly classify individuals with poor intellectual functioning specific to problems with perceptual accuracy or complexity. Furthermore, by uncovering the relationship between perceptual accuracy and problems with social functioning, clinicians in correctional settings can better address the specific needs of their patients.

The present study

While it appears that perceptual accuracy may relate to adaptive functioning, it is unclear whether severe deficits lead to more problem behaviors, including criminal activity. The present study was designed to address two specific goals. The first was to uncover how the Rorschach variables of form quality, complexity, and thought disturbance underlie the cognitive processes that influence IQ score as measured by the WAIS-IV. The second goal was to investigate how perceptual accuracy, thought complexity, and thought disturbance scores relate to problems with social functioning or criminal behavior. The current quantitative study involved an examination of archival data from two assessment sites to observe differences between the intellectual functioning, perceptual accuracy, and thought complexity of adult male prisoners compared to a normal sample. Data from adult male inmates from the men’s prison and adult male clients from the outpatient clinic were used. Each participant previously had been administered a psychodiagnostic battery that included the WAIS-IV, Rorschach (using the R-PAS scoring method), and the PAI or MMPI- 2. The study involved exploring the relationship between Rorschach cognitive variables (perceptual accuracy, thought complexity, and thought disturbance) and intellectual/perceptual ability as measured by the WAIS-IV. In addition, it involved an examination of differences between the two samples on R-PAS performance, as well as differences that existed within the incarcerated sample by designated level of care.

Null hypotheses

Five hypotheses (stated in null form) were determined based on the findings from the literature:

A. Hypothesis 1: There will be no significant difference between participants’ performance on Rorschach cognitive variables (form quality, thought complexity, and thought disturbance scores) based on intellectual ability.

B. Hypothesis 2: There will be no significant difference between participants’ performance on Rorschach cognitive variables (form quality, thought complexity, and thought disturbance scores) based on perceptual ability (PRI).

C. Hypothesis 3: There will be no significant difference in R-PAS variables (form quality, thought complexity, and thought disturbance) between offenders and outpatient subjects.

D. Hypothesis 4: There will be no significant difference in R-PAS variables (form quality, thought complexity, and thought disturbance) between varying degrees of institutional care level for offenders (GOB, CCCSM, MHCB).

E. Hypothesis 5: There will be no significant interaction effect between incarceration status and level of cognitive functioning on R-PAS variables.

Considering that the Rorschach variables of form quality, thought complexity, and thought disturbance have demonstrated some relation to intellectual ability, it was expected that participants with lower FSIQ and PRI scores would show greater impairment levels on these Rorschach variables. Furthermore, as problems with perceptual accuracy, thought complexity, and thought disturbance have been demonstrated to be related to psychopathology, learning disabilities, and poor social functioning, it was expected that offenders would demonstrate greater problems on these variables when compared to an outpatient sample.

Methods

Participants

A purposeful and convenient sample was collected using archival data from the men’s prison in California, and from the outpatient clinic in California. The archival data from the prison consisted of previously collected test batteries that were administered by psychodiagnostic practicum students with adult male offenders who were referred for psychodiagnostic assessment. Archival data from the outpatient clinic consisted of previously obtained test batteries also administered by psychodiagnostic practicum students with adult males (>18 years) who were referred for psychodiagnostic or neuroeducational assessment. All testing completed from both sites was supervised by a licensed psychologist. Only complete batteries were considered for the current study. A complete battery consisted of a WAIS-IV, PAI or MMPI-2, and a Rorschach using the R-PAS scoring system. Data from participants were excluded if the presence of a previously diagnosed brain injury, psychotic disorder, or dementia was indicated in their case file. Data collected from the outpatient clinic were also excluded for those participants with a reported history of arrest. Test validity of the remaining participants was then screened using the validity scales of either the PAI or MMPI-2. Only those participants with valid profiles were used for this study, resulting in 36 participants from the CIM and 43 from AUTAPS for a total of 79 participants.

The mean subject age of the inmate sample (n = 36) was 44.33 (SD = 14.48) years. The mean subject age of the outpatient sample (n = 43) was 28.51 (SD = 9.95) years. Education for the entire sample (N = 79) ranged from 6-22 years. The mean education level for the inmate sample was 11.64 (SD = 2.53) years, while the mean education level for the outpatient sample was 14.16 (SD = 2.71) years. Ethnic background for the sample demonstrated a diverse pool with 54.5% identifying as White, 15% as Latino, 4% as African American, 4% as Asian, 2% as Native American, 5% as multiracial, and 1% as another ethnic background.

Measures

Wechsler adult intelligence scale-IV: The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-IV (WAIS-IV [7]) was used to provide a measure of general intellectual functioning and perceptual reasoning ability. The WAIS is a well-established scale with high consistency. According to the test manual, over a 2-12-week time period, test– retest reliabilities ranged from 0.70 (seven subscales) to 0.90 (two subscales). Inter-rater coefficients were high, all being above 0.90. The WAIS-IV is also correlated highly with the Stanford-Binet IV test (0.88).

Rorschach inkblot technique: The Rorschach was used to assess perceptual accuracy, complexity of thought processes, and thought disturbance using the R-PAS scoring system [16]. The R-PAS scoring system was normalized using an international reference sample of 640 individuals. About one fifth came from the United States and about two thirds from nine European countries. Validity was established by correlating the scales with other known measures. For instance, Weiner found an effect size “almost identical” to the MMPI [17]. Viglione and Taylor demonstrated a strong inter-rater reliability between 85% and 99% [18]. Exner (as cited in Groth-Marnat) reported test–retest reliabilities from 26-92 over a 1-year interval considering 41 variables [19].

Several specific R-PAS variables were used in this study to investigate perception and thinking domains. Form quality (FQ) is designed to measure the accuracy of the forms involved in a response; in other words, how well a response fits the blot contours at the location on the card. As such, form quality percentages (FQ-%, WD-%, FQo%, and FQu%) generally measure the conventionality of perception and reality testing. FQ-% is a measure of distortion or misinterpretation, often leading to poor judgments or unconventional behavior. WD-% more specifically indicates whether distortion or misinterpretation occurs even in perceptual situations that are more commonly selected. FQo% is a measure of conventional judgment, while FQu% measures unconventional and individualistic ways of interpreting the world. Additional cognitive variables were used that are generally associated with thought complexity and thought disturbance. Complexity is a variable that measures differentiation, integration, and productivity at the response level. It is derived from the sophistication of location, space, and object qualities within one’s response. The Form % variable relates to the proportion of pure form responses in a record and is generally considered to be the opposite of the Complexity variable (i.e., simplicity). The Ego Impairment Index-3 (EII-3) is a broad measure of thinking disturbance with the components of reality testing, thought disturbance, crude and disturbing thought content, and measures of interpersonal misunderstanding and disturbance. The Thought & Perception Composite (TP-Comp) assesses reality testing and thought disorganization. Finally, the Weighted Sum of the Six Cognitive Codes (WSumCog) is a measure of disturbed and disordered thought. Procedures.

Archival data collected from CIM involved the testing of offenders who had been referred for psychodiagnostic evaluation. At the time of testing, subjects were provided an informed consent that explained their rights to confidentiality along with the process of neuropsychological evaluation. Subjects were then administered a battery that minimally included the WAIS-IV, the Rorschach (using the R-PAS scoring system), and the PAI or MMPI-2. The batteries were administered by psychodiagnostic practicum students who were supervised by a licensed psychologist. Once the testing had been completed, subjects were provided with a feedback session to discuss the findings of the evaluation.

Archival data collected from the AUTAPS clinic involved the testing of adult males who had been referred for psychodiagnostic or neuroeducational evaluation. At the time of testing, subjects were also provided with an informed consent that explained their rights to confidentiality and the process of neuropsychological evaluation. Subjects were then administered a battery that also minimally included the WAIS-IV, the Rorschach (using the R-PAS scoring system), and the PAI or MMPI-2. Once the testing had been completed, subjects were provided with a feedback session to discuss the findings of the evaluation.

For the purpose of this study, the researcher reviewed all available psychological assessments completed by psychodiagnostic practicum students from both the CIM and AUTAPS locations that met the inclusion criteria. All psychological test data and reports were kept confidential in a locked file cabinet in the corresponding office of each assessment program’s supervisor. Archival data and specific test score data were put into a spreadsheet with an ID number, so all assessment data were de-identified and aggregated. All the information was stored on a password-protected computer to which only the researcher and his supervisor had access. Demographic information such as age, race, and education level were accumulated into a spreadsheet format along with the prevalence and incidence rates of all other relevant variables. Any information that could identify the subjects was excluded from the data collection, including name, inmate number, date of birth, place of origin/crime, and any unique developmental/life characteristics or experiences.

Case information from the prison was then grouped according to level of care: general prison population (GOP), clinical care case management system (CCCMS), and mental health crisis bed (MHCB). Data from the outpatient clinic participants were grouped as the outpatient sample. From the WAIS-IV, the FSIQ, VCI, PRI, WMI, and PSI were recorded to account for the individual’s intellectual and perceptual ability. Scores were then grouped into seven categories according to the classification descriptions of the WAISIV: Extremely Low, Borderline, Low Average, Average, High Average, Superior, and Very Superior. From the R-PAS, variables that account for perceptual accuracy (FQ-%, WD-%, FQo%, and FQu%), thought complexity (Complexity, F%), and thought disturbance (WSumCog, TP-Comp, and EII-3) were recorded. Adjusted R-PAS scores using the R-Optimized administration were recorded and assessed for the purpose of this study.

Results

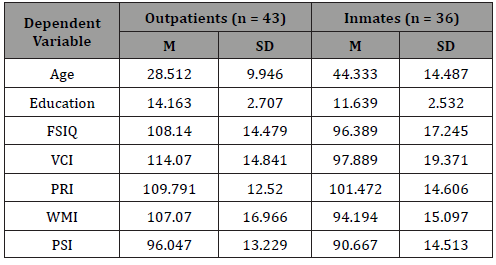

Statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS software package. Descriptive statistics were computed for all demographic variables. Comparisons between age, education, and the two IQ score measures (Full Scale IQ Score and Perceptual Reasoning Index) based on incarceration status were examined using independent samples t tests. The results are reported below, and the means and standard deviations are presented in Table 1. Relationships between subjects’ R-PAS performance on perceptual accuracy (FQ-%, WD- %, FQo%, and FQu%), thought complexity (Complexity, F%), and thought disturbance (WSumCog, TP-Comp, and EII-3) and variables of level of care, incarceration status, cognitive functioning, and perceptual reasoning were analyzed using multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs). Follow-up analyses using age and education as covariates were also conducted.

Independent samples T tests

An independent-samples T test was conducted to compare age differences between the samples of outpatient and inmate subjects. The incarcerated sample was found to be significantly older than the outpatient sample; t (60.253) = -5.549, p = .000. The means and standard deviations are reported in Table 1.

Table 1: Independent t Test Results.

An independent-samples T test was conducted to compare differences in level of education between the samples of outpatient and inmate subjects. The outpatient sample was found to have a significantly higher level of education compared to the inmate sample; t (77) = -4.250, p = .000. The means and standard deviations are reported in Table 1.

An independent-samples T test was conducted to compare differences in FSIQ scores between the sample of outpatient and inmate subjects. The outpatient sample was found to have significantly higher FSIQ scores compared to the inmate sample; t (77) = 3.293, p = .001. The means and standard deviations are reported in Table 1.

An independent-samples T test was conducted to compare differences in PRI scores between the sample of outpatient and inmate subjects. The outpatient sample was found to have significantly higher PRI scores compared to the inmate sample; t (77) = 2.726, p = .008. The means and standard deviations are reported in Table 1.

An independent-samples T test was conducted to compare differences in VCI scores between the sample of outpatient and inmate subjects. The outpatient sample was found to have significantly higher VCI scores compared to the inmate sample; t (77) = 4.201, p < .001. The means and standard deviations are reported in Table 1.

An independent-samples T test was conducted to compare differences in WMI scores between the sample of outpatient and inmate subjects. The outpatient sample was found to have significantly higher WMI scores compared to the inmate sample; t (77) = 3.531, p = .001. The means and standard deviations are reported in Table 1.

An independent-samples t test was conducted to compare differences in PSI scores between the sample of outpatient and inmate subjects. No significant difference was observed. The means and standard deviations are reported in Table 1.

Multivariate analysis of variance of effects of FSIQ on R-PAS variables

A MANOVA was used to examine form quality (FQ-%, WD-%, FQo%, and FQu%), thought complexity (Complexity, F%), and thought disturbance (WSumCog, TP-Comp, and EII-3) as dependent variables (DVs), and FSIQ score (Extremely Low, Borderline, Low Average, Average, High Average, Superior, and Very Superior) as the independent variable (IV). The multivariate analysis showed a multivariate effect for intellectual functioning, Wilk’s Lambda = .212, F (54,330.931) = 2.179, p < .001, indicating a difference in form quality and thought complexity among the different levels of intellectual functioning. Thus, Hypothesis 1, which was that there would be no significant difference in the R-PAS variables based on intellectual ability (FSIQ), was rejected.

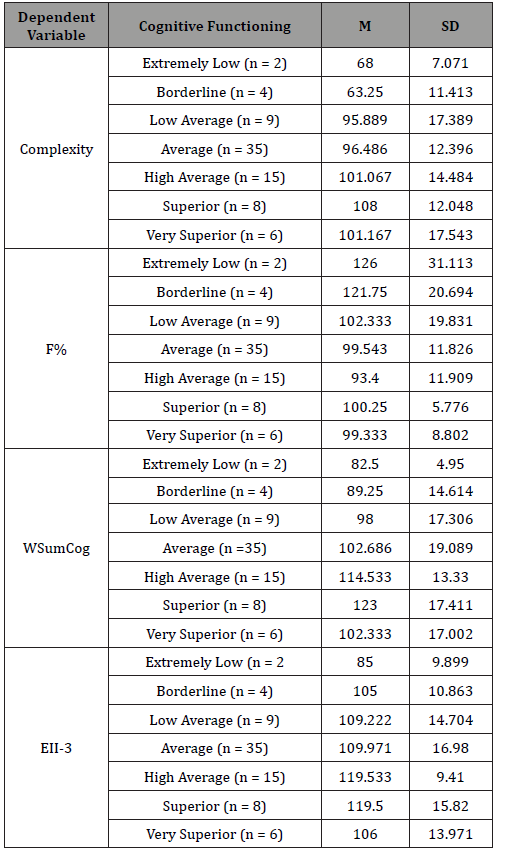

Because the overall MANOVA was significant, univariate ANOVAs were conducted to determine which specific dependent variables showed differences among the different levels of intellectual functioning using FSIQ. The univariate F tests showed there were significant differences among the levels of intellectual functioning on Complexity scores, F = 6.674, df = (6,72), p < .001; F% scores, F = 3.699, df = (6,72), p = .003; and WSumCog scores, F=3.698, df =(6,72), p = .003. FQ-% scores approached conventional levels of statistical significance, F = 1.484, df = (6,72), p = .196, while the remaining variables were found to be not significant. A follow-up analysis using age and education as covariates resulted in similar findings.

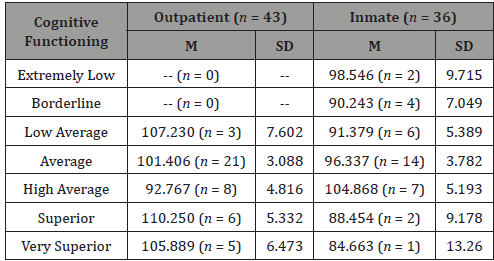

Table 2: (continued): Means and Standard Deviations (FSIQ).

To determine which IQ levels differed from each other on each of the cognitive functioning variables, post-hoc analyses using Tukey’s HSD were conducted. The means for each of these comparisons were presented in Table 2. These results of the analyses are reported below separately for each variable.

Complexity: As can be seen in Table 3, the following FSIQ comparisons were statistically significant on Complexity

Table 3: Significant Differences Between FSIQ Level on Complexity Scores.

Form%: As can be seen in Table 4, the following FSIQ comparisons were statistically significant on Simplicity.

Table 4: Significant Differences Between FSIQ Level on Form% Scores.

Weighted sum of the six cognitive codes (WSumCog): As can be seen in Table 5, the following FSIQ comparisons were statistically significant on WSumCog.

Table 5: Significant Differences Between FSIQ Level on WSumCog Scores.

Multivariate analysis of variance of effects of PRI on R-PAS variables

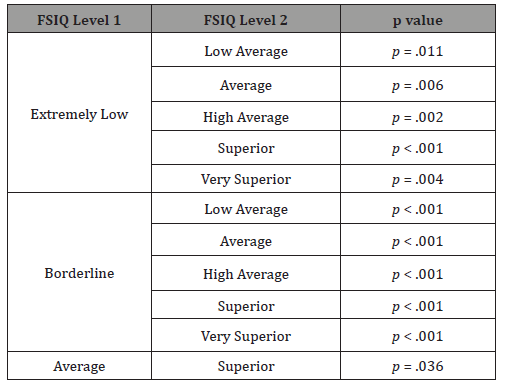

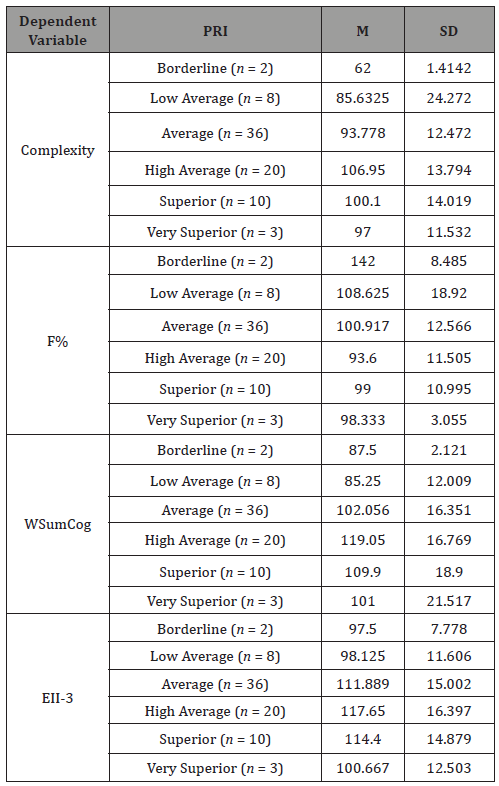

An additional MANOVA was used to examine form quality (FQ- %, WD-%, FQo%, and FQu%), thought complexity (Complexity, F%) and thought disturbance (WSumCog, TP-Comp, and EII-3) as dependent variables (DVs), and level of perceptual reasoning ability (Extremely Low, Borderline, Low Average, Average, High Average, Superior, and Very Superior) as the independent variable (IV). The multivariate analysis showed a significant multivariate effect for level of perceptual reasoning in relation to the R-PAS variables, Pillai’s Trace=.945, F(45,345) = 1.786, p = .002, indicating an overall difference in performance on the R-PAS between level of perceptual reasoning. Thus, Hypothesis 2, that there would no significant difference in R-PAS variables based on perceptual ability (PRI), was rejected. The univariate F tests showed there were significant differences among levels of perceptual reasoning on Complexity scores, F = 5.666, df = (5,73), p < .001; F% scores, F = 6.185, df = (5,73), p < .001; WSumCog scores, F = 6.086, df = (5,73), p < .001; and EII-3 scores, F = 2.707, df = (5,73), p = .027. The remaining variables were found to be not significant. A follow-up analysis using age and education as covariates resulted in similar findings. The means and standard deviations for each measure for each level of PRI are presented in Table 6.

Table 6: Means and Standard Deviations (PRI).

To determine which IQ levels differed from each other on each of the perceptual reasoning variables, post-hoc analyses using Tukey’s HSD were conducted. The means for each of these comparisons were presented in Table 6. These results of the analyses are reported below separately for each variable.

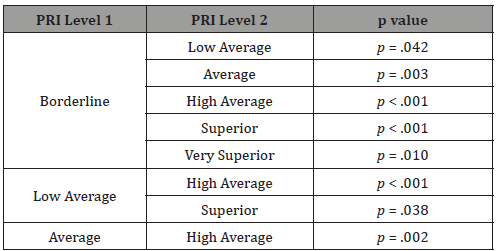

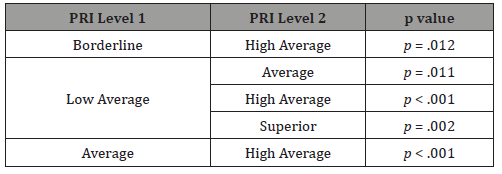

Complexity: As can be seen in Table 7, the following PRI comparisons were statistically significant on Complexity.

Table 7: Significant Differences Between PRI Level on Complexity Scores.

Form % (F%): As can be seen in Table 8, the following PRI comparisons were statistically significant on F%.

Table 8: Significant Differences Between PRI Level on Simplicity Scores.

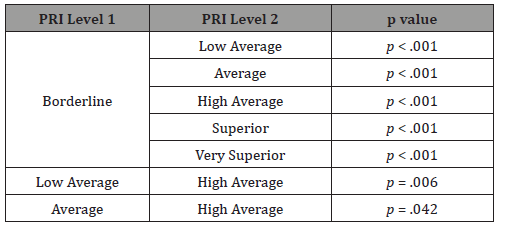

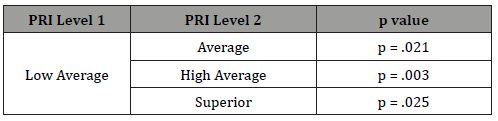

Weighted sum of the six cognitive codes (WSumCog): As can be seen in Table 9, the following comparisons were statistically significant on WSumCog.

Table 9: Significant Differences Between PRI Level on WSumCog Scores.

0Ego impairment index-3 (EII-3): As can be seen in Table 10, the following comparisons/differences were statistically significant on EII-3. An analysis using age and education as covariates yielded similar findings.

Table 10: Significant Differences Between PRI Level on EII-3 Scores.

Differences Between Incarcerated and Outpatient Samples

A MANOVA was used to examine form quality (FQ-%, WD-%, FQo%, and FQu%), thought complexity (Complexity, F%), and thought disturbance (WSumCog, TP-Comp, and EII-3) as dependent variables (DVs), and incarceration status (Outpatient, Inmate) as the independent variable (IV). The multivariate analysis showed no significant multivariate effect for incarceration status in relation to the R-PAS variables. The univariate F tests also showed no significant difference between incarceration status in relation to the R-PAS variables. However, most of the differences were in the expected direction although they did not reach statistical significance. A follow-up analysis using age and education as covariates resulted in similar findings. Thus, Hypothesis 3, which was that there would be no significant difference in R-PAS variables between incarcerated and non-incarcerated subjects, failed to be rejected.

Differences Within Incarcerated Sample Using Institutional Care Level

A final MANOVA was conducted with the independent variable consisting of the three levels of care of the incarcerated subjects: General Population (GOP), Correctional Clinical Case Management System (CCCMS), and Mental Health Crisis Bed (MHCB). Form quality (FQ-%, WD-%, FQo%, and FQu%), thought complexity (Complexity, F%), and thought disturbance (WSumCog, TP-Comp, and EII-3) were used as the dependent variables (DVs). The multivariate analysis showed no significant multivariate effect for level of care status in relation to the R-PAS variables, indicating no overall differences in form quality and thought complexity among the levels of care.

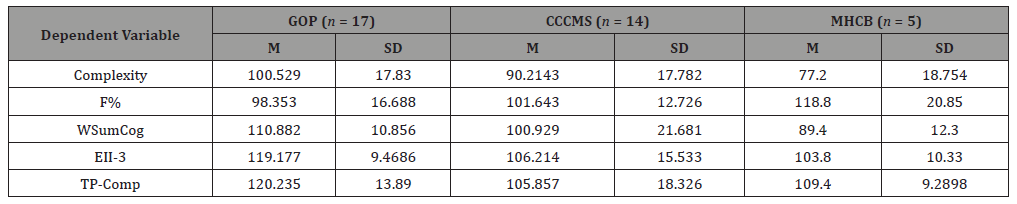

Although the overall MANOVA was not statistically significant, univariate ANOVAs were conducted to examine differences between specific dependent variables among the different levels of care. The univariate F tests resulted in significant differences between levels of care on Complexity scores, F = 3.607, df = (2,36), p = .038; F% scores, F = 3.243, df = (2,36), p = .052; WSumCog scores, F = 3.842, df = (2,36), p = .032; EII-3 scores, F = 5.548, df = (2,36), p = .008; and TP-Comp scores, F = 3.530, df = (2,36), p = 041. The remaining variables were found to be not significant. Thus, Hypothesis 4, which was that there would be no significant difference in R-PAS variables between the designated levels of care within the incarcerated sample, was rejected. The means and standard deviations for each measure for each level of care within the incarcerated sample are presented in Table 11.

Table 11: Means and Standard Deviations for Incarcerated Sample by Level of Care.

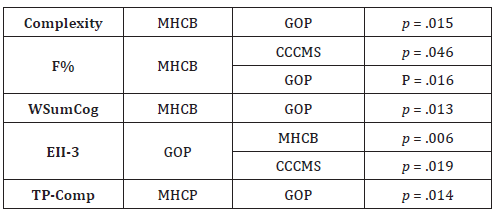

To determine which care levels were significantly different from one another on each of the R-PAS variables, Post-hoc analyses using Tukey’s HSD were conducted. The means for each of these comparisons were presented in Table 11. Significant differences between the care level groups for each variable are presented in Table 12.

Table 12: Significant Pairwise Differences Between Level of Care on R-PAS Variables.

Interaction Analysis Between Incarceration Status and Cognitive Functioning

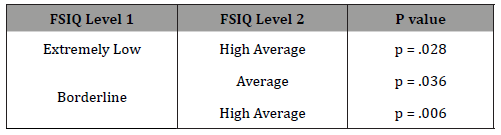

A MANOVA using age and education as covariates was used to examine the interaction between subjects’ intellectual functioning and incarceration status. The analysis again examined form quality (FQ-%, WD-%, FQo%, and FQu%), thought complexity (Complexity, F%), and thought disturbance (WSumCog, TPComp, and EII-3) as dependent variables (DVs), and FSIQ score (Extremely Low, Borderline, Low Average, Average, High Average, Superior, and Very Superior) as the independent variable (IV). The multivariate analysis showed an interaction effect between intellectual functioning and incarceration status that approached conventional levels of statistical significance, Wilk’s Lambda = .480, F (36,215.343) = 1.295, p = .135. Though not significant at this level, a potential interaction between a subject’s intellectual functioning and incarceration status may mediate performance on the R-PAS variables.

Although the overall MANOVA was not statistically significant, univariate ANOVAs were conducted to examine differences between the dependent variables as a result of the interaction of incarceration status and cognitive functioning. The univariate F tests showed there was a significant interaction effect on FQu%, F = 2.873, df = (4,65), p = .030. The remaining variables did not demonstrate any significance with respect to the interaction between intellectual functioning and incarceration status. Thus, Hypothesis 5, which was that there would not be an interaction effect between intellectual ability and incarceration status on R-PAS variables, was rejected.

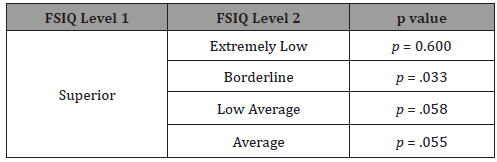

To determine where the interaction effect was evident within the FQu% scores, a Post-hoc analysis using Tukey’s HSD was conducted. The means for each of these comparisons are presented in Table 13.

Discussion

The present study was designed to address several specific goals. The first was to determine how performance on the cognitive scales of the Rorschach related to cognitive functioning via measures of intellectual ability and perceptual reasoning. The second was to analyze the differences between incarcerated and non-incarcerated individuals regarding their performance on the Rorschach variables associated with perceptual accuracy, thought complexity, and thought disturbance. Last, the study involved an investigation of the differences on the same cognitive measures of perceptual accuracy, thought complexity, and thought disturbance from the Rorschach among the different designated institutional care levels within the incarcerated sample (i.e., general population, clinical case management system, and mental health crisis bed).

The hypotheses for this study were that there would be a significant relationship between performance on the cognitive scales of the Rorschach and intellectual and perceptual ability as measured by the WAIS-IV; that inmates would demonstrate a greater degree of problems with perceptual accuracy, thought complexity, and thought disturbance when compared to nonincarcerated individuals; and that these perceptual problems would be more represented with inmates evidencing a greater degree of social/psychological functioning as indicated by their designated institutional care level. It was expected that this study would begin to uncover underlying aspects of cognition specific to perceptual ability that affect decision-making and approach to problemsolving and validate the utility of the Rorschach in assessing these important features of cognitive style, especially with regard to incarcerated individuals.

Findings with respect to differences in intellectual ability between incarcerated and non-incarcerated individuals were consistent with the literature review [5,6], Overall intellectual ability was found to be significantly higher in the non-incarcerated sample. Although both samples performed within the average range for FSIQ, offenders exhibited an average percentile rank of 39% while non-offenders exhibited a percentile rank of 70%. Specific differences were found on measures of verbal comprehension, perceptual reasoning, and working memory. Not surprisingly, the biggest difference between the two groups was found within the Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI). On average, offenders scored within the 44th percentile for VCI while the average non-offender scored within the 82nd percentile. However, it is likely that these discrepancies were mediated by the demographic differences observed between the two samples. For instance, the incarcerated sample comprised relatively older men with lower educational attainment. Taken together, these variables may capture differences in the quality of education or in exposure to academic material over time. Performance differences between the two samples may therefore highlight differences in educational experience rather than true intellectual impairment within the incarcerated sample. Prior studies have demonstrated how measures of verbal comprehension are closely associated with academic experience [13]. This relationship exposes the potential for test bias, especially when used with populations that are considered underprivileged or vulnerable to the negative impact of socioeconomic status. This is especially significant in the assessment of offenders as a vast majority of these individuals come from disadvantaged areas mediated by social constructs that do not place as much emphasis on academic achievement. Intellectual measures may then pose a greater disadvantage for these individuals by proposing false positives for cognitive deficits or dysfunction. This is one reason perceptual measures like the PRI are considered less “biased” when it comes to intellectual “ability” [13].

Another important finding involved the differences between the VCI and PSI of the non-incarcerated sample. On average, subjects exhibited a VCI score of 114 and a PSI score of 96; a significant difference of 18 points. This relative weakness in processing speed may illustrate the cognitive difficulties specific to this clinical sample. One important consideration that is discussed later is that this sample sought services for academic accommodations or diagnostic clarification of ADHD. Thus, the specified difference between VCI and PSI performance may be indicative of such cognitive deficiencies.

As expected, performance on the cognitive measures of the Rorschach was found to be correlated to overall intellectual functioning as measured by FSIQ score. Complexity and Form% scores demonstrated correlations with FSIQ in that higher levels of cognitive ability were associated with more intricate and descriptive responses. This is consistent with findings from the literature review, which supported that the more intellectual capacity one possesses, the more complex and integrated thoughts he or she is likely to demonstrate in his or her characterization of the inkblots [20]. Interestingly, the Weighed Sum of Cognitive scores (WSumCog) also demonstrated an association with FSIQ, but in an unexpected way. The association revealed individuals with higher performance on FSIQ also exhibited more cognitive errors within their responses. However, this association may characterize the idiosyncratic quality or creativity involved in the formation of more complicated responses that may sometimes be coded as cognitive errors or deviations from the task. Measures of perceptual accuracy were not found to be significantly related to FSIQ score. However, FQ-%, which measures unconventional thought processes, was found to approach conventional statistical significance through an inverse relationship with overall cognitive ability. Qualitatively, this may indicate intellectual ability plays a fundamental role in the organization of ideas and perceptions into clear and accurate responses.

As the cognitive task of the Rorschach primarily involves the presentation of perceptual stimuli, performance on the cognitive variables of the R-PAS was compared more specifically to perceptual reasoning as measured by PRI scores of the WAIS-IV. Results confirmed findings from prior studies by demonstrating several relationships between the R-PAS cognitive variables and perceptual ability [21]. Complexity, F%, and WSumCog demonstrated a similar association to PRI score that was observed with FSIQ. Interestingly, the Ego Impairment Index (EII-3) also showed statistical significance with respect to perceptual reasoning, although a relationship with overall cognitive ability was not previously found. This effect may be characterized through the incorporation of more perceptually driven measures within the EII-3 variable, such as interpersonal misunderstanding. Like the association observed between WSumCog and FSIQ, a greater degree of misperceptions was exhibited with increased perceptual ability.

Again, this observation may be the result of the unconventional quality involved in more complicated responses. However, another possibility may be that both samples exhibited a greater degree of difficulties and misperceptions at higher levels of cognitive/ perceptual performance. If this is the case, the inconsistency between thought disturbance measures and cognitive/perceptual ability may hold clinical relevance in terms of specifying psychological dysfunction. This hypothesis is discussed in greater detail later through a consideration of the clinical dynamics underlying the composition of the samples used in this study. Nevertheless, findings support research conclusions that the successful completion of the Rorschach task does require adequate levels of perceptual ability [21]. Individuals with lower perceptual ability appear to be less engaged in the task, responding with a higher degree of overly simplistic characterizations of the inkblots. However, perceptual ability appears to lose its effect beyond more adequate levels of performance. In other words, higher perceptual ability does not necessarily provide an advantage for individuals in their completion of the Rorschach task beyond normative ability levels.

Significant differences between the incarcerated sample and non-incarcerated sample on the Rorschach variables were not found. In general, both groups exhibited performances within the average range for all of the cognitive variables assessed (i.e., Complexity, Form%, FQ-%, FQo%, FQu%, WD-%, WSumCog, TPComp, and EII-3). This suggests comparable levels of functioning within the domains of perceptual accuracy, thought complexity, and thought disturbance despite incarceration status. These observations may be supportive of findings reported by Beaver and Wrigh, t which demonstrated how general cognitive ability did not necessarily mediate criminal behavior [22]. Therefore, the general prison population may be expected to function at a level that is like that of the rest of the population when it comes to cognitive tasks. Moreover, studies that have demonstrated differences in Rorschach performance mediated by antisocial traits typically included more extreme criminals in their samples (i.e., individuals exhibiting a high level of psychopathy traits), as in the Franks et al. study [23]. Although type of crime was not a factor assessed within this study, it could be an important consideration as it may mediate differences between offenders and the rest of the population.

Another important consideration that may account for the findings involves the composition of the comparison sample used in this study. One of the primary motivating factors for obtaining services within this sample involved assessment for academic accommodations either related to a potential learning disability or ADHD. Therefore, a more realistic interpretation of the findings may be that offenders perform more similarly to individuals with learning disabilities, or at least to those with a higher degree of cognitive complaints. This hypothesis was supported through the comparison of several studies discussed within the literature review. For instance, juvenile offenders within the Anderson and Walsh study yielded a similar cognitive profile on the Rorschach compared to the ADHD adolescents assessed by Cotugno [24,25]. Studies using other forms of neuropsychological assessments have also demonstrated correlations between attention deficit indices and number of previous convictions, suggesting recidivists may have an attention disorder profile [26]. This relationship may explain the inconsistency overserved in both samples between high cognitive/perceptual ability and increased rates of thought disturbance measured by WSumCog and EII-3. Despite a capacity for higher cognitive/perceptual performance, these individuals demonstrated an ineffective approach that may be indicative of psychological dysfunction. To further investigate this relationship, a more thorough discussion of performance within each of the cognitive domains is required.

Qualitative differences between the general performance of the two groups carry clinical relevance in terms of specifying cognitive style. Approach to problem-solving, for instance, was relatively distinct between the two samples. Offenders generally approached the Rorschach with more reservation, defensiveness, and uncertainty. Furthermore, offender responses were generally more simplistic, less integrative, and less vivid when compared to non-offenders. This difference in style is likely to be explained by a few variables. One explanation may involve the effects of traumatic numbing. According to the R-PAS manual, a history of trauma can result in avoidant and constricted responses through low complexity scores [16]. Thus, it is possible that offenders’ cognitive styles may have been influenced by the presence of traumatic experiences. Another important consideration lies within distinctions of the environments in which the assessments were administered. Correctional settings involve several specific challenges to treatment and assessment. Confidentiality, for instance, is often constrained by the need to maintain security and safety. Offenders are likely to be deterred from providing important information relevant to their case for fear of having the information used against them. Furthermore, in many correctional settings, clinicians operate under a dual role to enforce policy and manage facility procedures. This may directly interfere with the therapeutic relationship between offender and clinician by inducing mistrust and resistance. Evaluations are also typically mandated, or court ordered. Thus, compared to clients assessed in the community, offenders are more likely to arrive to their evaluations unmotivated, uninterested, or simply unwilling to participate. Together, these factors challenge the conditions of therapy and assessment in a manner that is likely to affect one’s cognitive approach. Increasing support for this distinction in cognitive style is evident when the offenders’ performance is interpreted from a normative scale.

The form quality variables (i.e., FQo%, FQu%, FQ-%, and WD- %) measure the capacity for conventional responses and accurate perceptions. While it was expected that offenders would exhibit a greater degree of misperceptions related to errors in judgment, significant differences between the samples were not found. The FQo% and FQu% variables measure the degree of responses involving perceptions that are generally considered to be easily identified. Interestingly, offenders exhibited relatively higher FQo% with a percentile rank of 40% compared to the 30th percentile rank of non-offenders. This suggests offenders’ function generally well in more predictable environments or with stimuli that may be more familiar. Moreover, offenders exhibited relatively fewer FQu responses with a percentile rank of 35% compared to the 55th percentile rank of non-offenders. Thus, in more common situations, offenders may be more inclined to provide conventional responses as opposed to responses that may be more individualistic or creative. FQ- responses are considered atypical perceptions that may be indicative of faulty interpretation of environmental stimuli. As such, it was expected that offenders would exhibit a higher frequency of FQ- responses. Although not significantly different from the comparison sample (76th percentile rank), offenders generally scored within the 82nd percentile on FQ-%, suggesting a greater degree of unconventional or inaccurate perceptions. Considering the normative performance exhibited with more predictable cues, it is likely that these misperceptions occurred when offenders faced more ambiguous stimuli. Thus, offenders may experience greater difficulty in more novel situations. WD-% is like FQ-% but focuses on measuring more pervasive misperceptions that occur in more common or obvious features of the environment. Again, offenders generally demonstrated higher prevalence for WD- responses, scoring at the 80th percentile while non-offenders performed at the 70th percentile. Thus, compared to a normative sample, offenders did demonstrate relative problems with perceptual accuracy and conventionality even under circumstances considered to be easily interpreted or obvious. This may identify an underlying component of cognitive approach that likely limits the ability to accurately appraise a situation and respond appropriately.

Thought complexity variables (i.e., Complexity and F%) measure the degree of creativity, sophistication, and integration within one’s response. Consistent with the conceptualization that inmates exhibit a greater degree of problem-solving difficulties, it was expected that the incarcerated sample would demonstrate a lower degree of complexity within their responses. Although no significant differences were found between the two samples, offenders generally performed within the 27th percentile on Complexity while non-offenders performed within the 42nd percentile. Furthermore, offenders performed within the 70th percentile on Form% while non-offenders performed within the 50th percentile. Together, these findings support expectations in that offenders demonstrated relatively less creativity, sophistication, and engagement within their responses. This may relate to a general lack of flexibility or adaptiveness to ambiguous stimuli. According to the interpretation of the R-PAS, a lack of complexity in responses is also generally associated with inadequate psychological resources and a limited ability to engage in the world. However, this difference may also be attributed to mistrust or disinterest in the task itself. As previously mentioned, traumatic numbing may also be an influential factor especially in more extreme cases of disengagement. Nevertheless, overall offender response style is suggestive of approaching the world in a manner that is disengaged, distant, and uninvolved.

Thought disturbance variables (i.e., WSumCog, TP-Comp, and EII-3) measure aspects of reality testing, disorganization, disturbed thought content, interpersonal misunderstandings, and immature or ineffective thinking. It was expected that offenders would demonstrate a higher frequency of thought disturbance compared to non-offenders. With respect to the WSumCog, offenders performed within the 63rd percentile while non-offenders performed within the 50th percentile. This suggests an increased level of disorganized thought or immaturity among offenders in the sample. On TP-Comp, offenders scored within the 79th percentile while non-offenders scored within the 68th percentile. This suggests relatively increased levels of disorganized thought and problems with reality testing. Finally, with respect to EII-3, offenders scored within the 72nd percentile while non-offenders scored within the 68th percentile. This suggests relatively increased levels of crude and disturbing thought content as well as interpersonal misunderstandings. Interestingly, both samples generally scored higher on these variables compared to the normative sample. However, this makes sense as the thought complexity variables are generally considered to be associated with increased levels of psychopathology. Both samples obtained assessments because they sought psychological services. Thus, both samples likely presented with heightened levels of psychological complaints when compared to the general population, thereby potentially contributing to differences in thought disturbance. Considering the relative heightened scores for offenders within this domain, it may be inferred that offenders, or rather the experience of being incarcerated, may make these individuals increasingly susceptible to thought disturbance.

Understanding the components of offender cognitive style pushed the investigator of this study to explore the differences within the incarcerated sample that might mediate social dysfunction within the prison environment itself. An overall difference was captured between the varying degree of institutional care levels assigned to the incarcerated sample based on their need for psychological services. Performance differences on Complexity, F%, WSumCog, EII-3, and TP-Comp were found to exist between the three groups of designated care levels. In general, offenders with a higher need for services exhibited more simplistic and less integrative responses with a higher percentage of thought disturbances, interpersonal misunderstandings, and immature or ineffective thinking. Primary differences existed between the offenders with the highest need for psychological treatment (MHCB) and offenders in the general population (GOP). Interestingly, significant differences between MHCB offenders and offenders classified within the intermediate group (CCCMS) were found on F%. Thus, simplistic or unsophisticated thought processes may be an important factor in determining psychological health within a correctional institution and may benefit clinicians in designating need for treatment. Together, these findings demonstrate the utility of the Rorschach in enhancing clinical judgment by identifying inmates who are at a greater risk for psychological dysfunction, and in allowing clinicians to respond with interventions that are more specific to treatment needs.

Finally, the interaction between incarceration and cognitive functioning on performance on the Rorschach was investigated. Although no overall significant interaction effect was found, univariate analysis of FQu% did demonstrate some statistical relevance. Non-offenders exhibited performance trends on FQu% that would be considered typical for the general population in that the more cognitive reserve one maintains, the more individualistic his or her responses are expected to be. Offenders, however, exhibited a distinct trend in that higher levels of cognitive ability generally resulted in fewer individualistic or creative responses. Thus, offenders thought to be at more capable levels of cognitive performance seemed to prefer more conventional responses. As previously discussed, offenders are likely to approach the task of the Rorschach with a greater level of uncertainty and mistrust as a result of their incarceration status. Therefore, the experience of being incarcerated may influence offenders to present themselves in a more conventional way or respond in a manner that draws far less attention to themselves. This may be especially true for offenders who are more aware of perceived legal risks. Although FQu% is generally considered to be a less reliable variable the overall trend observed provided an important consideration in the assessment of the incarcerated population [16]. While the experience of incarceration may influence performance on psychological measures, the degree to which this influence is exhibited may be mediated by the offender’s level of sophistication.

Clinical implications

This study offers several important implications for clinical practice and society. First, several observations were made that are likely to enhance the overall accuracy of psychological assessment specific to the prison population. Second, the identified cognitive style of the offenders assessed in this study promotes the use of more cognitively driven interventions to more specifically treat offenders and potentially reduce recidivism rates. Last, findings from this study demonstrate the utility of the Rorschach in providing objective data to more accurately assess the treatment needs of incarcerated individuals.

The assessment of the prison population is often confounded by a few internal and external variables. Intellectual measures are often limited in their ability to accurately assess individuals of low socioeconomic status and ethnic minorities. Moreover, environmental factors specific to the correctional setting can influence the overall performance of the offender. Together, these factors have generally resulted in the tendency to over pathologize cognitive deficits within the prison population, and in some cases attribute criminal activity to these deficits. However, by demonstrating how performance-based measures, such as the Rorschach, relate to more traditional neurocognitive measures, this study offers critical information to enhance the assessment of the prison population. Findings from this study demonstrated that R-PAS cognitive variables correlated consistently with traditional variables of cognitive ability (i.e., FSIQ and PRI). Thus, by investigating inconsistencies in performance, clinicians may be more able to distinguish true cognitive impairment from profiles influenced by test bias or incarceration status. Specifically, psychological dysfunction or aspects of ineffective cognitive style may be specified when misperceptions occur despite adequate levels of cognitive ability. Incorporating this understanding into the assessment of offenders may then help to reduce the tendency to over pathologize cognitive dysfunction within this population.

The current study further offers important implications for the treatment and rehabilitation of offenders. Prior research has revealed several connections between cognitive deficits and criminal activity [27]. However, the current study clarified these empirical findings by uncovering how preferences in cognitive style contributed to criminal thinking patterns. Within the results of this study, offenders consistently demonstrated a cognitive style that was simplistic, disengaged, and immature regardless of intellectual/perceptual ability. This is likely to lead to a higher degree of misperceptions, inaccurate appraisals of situations, and impulsive decision-making. Thus, while criminal behavior may be independent of cognitive ability, it is likely facilitated through one’s preferred style or approach. This understanding provides support for the incorporation of cognitive rehabilitation models with the correctional framework. Offenders are likely to benefit from interventions such as rational self-analyses, which promote increased attention and the integration of environmental ques in order to improve their ability to appraise situations more accurately. By incorporating interventions that improve the effectiveness of cognitive style, treatment programs within the correctional framework may become more specific to the needs of the offender. In this way, it is possible that rehabilitation services can reduce recidivism rates within the incarcerated population.

Findings from this study also demonstrated important differences within the sample of offenders. Psychological dysfunction, as measured by the cognitive variables of the R-PAS, correlated with the designated level of care for each offender. That is, offenders requiring more extensive psychological services and crisis intervention consistently demonstrated more difficulties with respect to thought complexity and thought disturbance. Thus, the Rorschach may offer important objective data to enhance clinical judgment, especially in determining an individual’s need for services. This may offer specific benefits to clinicians practicing within a correctional setting as the designated care level of offenders frequently shifts depending on the institution and the inmate’s level of engagement in treatment. Objective data specific to the assessment of treatment needs may further serve additional benefits in terms of providing comparable data for program reviews.

Limitations and directions for future research

There are a few limitations to consider in this study. For instance, the small sample size (N=79) may have affected the overall generalizability of the findings. The researcher obtained data from 43 outpatients and 36 incarcerated subjects. This number restricted how well each sample could reliably represent its respective population. The reduced sample size also influenced the sensitivity of the findings. For instance, several of the measures were observed to approach conventional levels of statistical significance. Therefore, it is possible that a true effect may have been missed. As archival data were used in the completion of this study, the number of completed clinical profiles was limited. Future research studies are likely to benefit from a larger pool of clinical data to draw measurable conclusions specific to the cognitive styles of offenders.

Another important limitation involved the composition of the samples obtained. Client data from the outpatient clinic were essentially used as a control to compare with offender profiles. However, this sample was not a reliable representation of the general population for a few reasons. First, individuals from this sample exhibited some form of clinical need as they sought psychological services for one reason or another. Thus, the individuals assessed may have been more likely to present with a higher level of psychological or cognitive difficulties than would be expected for the general population. Second, data for this sample were obtained exclusively from one site in California. Thus, the outpatient sample was likely be more representative of the surrounding community the clinic services. Likewise, the data obtained to represent the offender sample were gathered exclusively from one site. This limited how well the offender sample could reliably represent the incarcerated population. One important factor is that the offender data were obtained from a state facility. Several important distinctions often exist between state and federal prison facilities that may affect the experience of incarceration. According to a report from the Bureau of Justice, state facilities hold significantly more violent criminals compared to federal facilities [2]. This creates important differences between both settings with respect to perceived risk, level of anxiety, and availability of social support. Level of security is another factor that mediates policy, operations, and interactions with staff for both state and federal settings.

Another important limitation of the study may be related to the differences that existed between the two testing sites themselves. Although participants from both settings were at one point referred for psychological services, the experience of the participants was likely to be different depending on the setting. Participants from the prison setting, for instance, may have approached the testing experience with greater defensiveness and caution. As discussed in the literature review, the experience of incarceration often carries specific challenges in psychological treatment and assessment. Issues of trust, dual relationships of correctional clinicians, and limitations of confidentiality all affect the atmosphere in which the assessment is administered within a correctional setting. In addition, correctional settings often involve greater time restrictions and distractions that are likely to affect the performance of offenders in some way. It is therefore important to take these and other potential confounding variables into consideration while interpreting the data of this study.

Another important consideration is that the assessments from both sites were administered by doctoral level students. In consideration of the limited experience level of these students, careful interpretation of the results is required as a higher degree of scoring error is possible. Nevertheless, students from both locations received similar training and supervision to account for their lack of experience in psychological assessment.

Future directions for research involve incorporating important factors not assessed within this study. For instance, the severity of cognitive codes within the thought disturbance domain was not assessed. Identifying distinctions between deviant responses and minor cognitive errors within this domain may help to shed light on the relationship between WSumCog and EII-3 within advanced levels of cognitive ability. Additional variables not assessed within this study included years of incarceration, number of criminal offenses, and type of offense. These factors likely hold important roles in mediating criminal involvement. Adaptation to the prison environment, for instance, may have some impact on an individual’s approach to problem-solving, especially while incarcerated. Whether that adaptation persists beyond the experience of confinement may be important in determining whether cognitive style underlies criminal thinking or is a consequence of such thinking.

Conclusion

This study was designed to explore what differences existed within the offender population that may account for assessment disparities suggestive of cognitive dysfunction. Assessment within the correctional environment may not be as accurate as a result of a few challenges. However, by understanding what differences are specific to the offender profile, clinicians can begin to utilize assessment measures more effectively to guide diagnosis, treatment needs, and intervention planning. This may help to increase the overall effectiveness of rehabilitation programs and thereby reduce the rates of recidivism. Findings from this study were indicative of a consistent relationship between the cognitive variables of the R-PAS and more traditional measures of cognitive ability. Observations specific to the performance of offenders also support the hypothesis that criminal activity occurs independent of cognitive ability. Rather, it appears that an ineffective approach to situations and a restricted level of engagement may lead to the unsuccessful use of cognitive potential. Taking this observation into consideration, this researcher recommends the use of cognitively driven interventions to improve the specific challenges offenders face in appraising situations and effectively applying problemsolving skills. Finally, findings from the current study uphold the utility of the Rorschach in providing an objective measure to enhance clinical judgment, especially when determining a patient’s need for services.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- Walmsley R (2016) World prison population list (11th edn).

- Carson A (2014) Prisoners in 2013 (NCJ 250229). Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, USA.

- Langan, PA, Levan DJ (2002) Recidivism of prisoners. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, USA.

- West HC, Sabol WJ, Greenman SJ (2011) Prisoners (NCJ 231675). Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, USA.

- Lindsay WR, Hastings RP, Griffiths DM, Hayes SC (2007) Trends and challenges in forensic research on offenders with intellectual disability. J Intellec Dev Disabil 32(2): 55-61.

- Sinclair M, Blencowe A, McCaig L, Misch P (2013) Neuropsychological findings from a forensic neuropsychology clinic at a South East London tier 4 CAMHS. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities 7(2): 93-107.

- Wechsler D (2008) Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Fourth edition: Technical and interpretive manual. San Antonio TX: Pearson, USA.

- Genders E, Player E (1995) Grendon: A study of a therapeutic prison. Clarendon Press, Oxford UK.

- Pitman I, Ireland CA (2003) Cognitive ability sex offender therapy. Forensic Update 73: 14-19.

- Newberry M, Shuker R (2011) The relationship between intellectual ability and the treatment needs of offenders in a therapeutic community prison. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry Psychology 22(3): 455.

- Heaton RK, Taylor MJ, Manly J (2003) Demographic effects and use of demographically corrected norms with the WAIS-III and WMS-III. In: DS Tulsky, DH Saklofske, GJ Chelune, RK. Heaton, et al. (Eds), Clinical interpretation of the WAIS-III and WMS-III. Academic Press, San Diego, USA, pp. 181-210.

- Shuttleworth Edwards AB, Kemp RD, Rust AL, Muirhead JGL, Hartmen NP, et al. (2004) Cross-cultural effects on IQ test performance: A review and preliminary normative indications on WAIS-III test performance. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 6(7): 903-920.

- Growth Marnat G, Wright AJ (2016) Handbook of psychological assessment (6th edn). John Wiley

- Perry W, Viglione D, Braff D (1992) The Ego Impairment Index and schizophrenia: A validation study. J Pers Assess 59(1): 165-175.

- Frank G (1979) On the validity of hypotheses derived from the Rorschach: V. The relationship between form level and ego strength. Percept Mot Skills 48(2): 375-384.

- Meyer GJ, Viglione DJ, Mihura JL, Erard RE, Erdberg P (2011) Rorschach Performance Assessment System: Administration, coding interpretation, and technical manual. Toledo, OH: Rorschach Performance Assessment System.

- Weiner IR (2001) Advancing the science of psychological assessment: The Rorschach Inkblot Method as exemplar. Psychol Assess 13(4): 423-432.

- Viglione DJ, Taylor N (2003) Empirical support for interrater reliability of Rorschach Comprehensive System coding. Journal of Clinical Psychology 59(1): 111-121.

- Growth Marnat G (2009) Handbook of psychological assessment (5th edn), Hoboken, John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, USA.

- Wood JM, Krishnamurthy R, Archer RP (2003) Three factors of the comprehensive system for the Rorschach and their relationship to Wechsler IQ scores in an adolescent sample. Assessment 10(3): 259-265.

- Smith SR, Bistis K, Zahka NE, Blais MA (2007) Perceptual-organizational characteristics of the Rorschach task. The Clinical Neuropsychologist 21(5): 789-799.

- Beaver KM, Wright JP (2011) The association between county-level IQ and county-level crime rates. Intelligence 39(1): 22-26.

- Franks KW, Sreenivasan S, Spray BJ, Kirkish P (2009) The mangled butterfly: Rorschach results from 45 violent psychopaths. Behav Sci Law 27(4): 491-506.

- Anderson LE, Walsh JA (1998) Prediction of adult criminal status from juvenile psychological assessment. Criminal Justice and Behavior 25(2): 226-239.

- Cotugno AJ (1995) Personality attributes of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) using the Rorschach Inkblot Test. J Clin Psychol 51(4): 554-562.

- Tuominen T, Korhonen T, Hamalainen H, Temonen S, Salo H, et al. (2013) Neurocognitive disorders in male offenders: Implications for rehabilitation. Crim Behav and Ment Health 24(1): 36-48.

- Herrnstein RJ, Murray C (1994) The bell curve: Intelligence and class structure in American life. Free Press, New York, USA.

-

Alberto Miranda, Stephen E Berger, Bina Parekh, Ashley Ginter. Perceptual Accuracy and Thought Complexity of a Correctional Population with the Wechsler IQ Test and the Rorschach. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 3(2): 2020. OAJAP.MS.ID.000557.

Incarcerated and non-incarcerated, Rorschach variables, Nevertheless, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV), Neuropsychological deficits, Rorschach Performance Assessment System (R-PAS), Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI), Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2), Criminal behavior, Brain injury.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of the Problem

- Methods

- Results

- Differences Between Incarcerated and Outpatient Samples

- Differences Within Incarcerated Sample Using Institutional Care Level

- Interaction Analysis Between Incarceration Status and Cognitive Functioning

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgment

- Conflict of Interest

- References