Research Article

Research Article

Online Group Psychotherapy for Addiction During Covid-19

Leah Orme, Andre Geel C*

Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust, Willesden Centre for Health & Care, UK.

Andre Geel, Brent New Beginnings Recovery Day Programme, Willesden Centre for Health. Harlesden Road, London, UK.

Received Date: January 04, 2020; Published Date: March 09, 2021

Abstract

Aim: This study aimed to analyse the transition to online group psychotherapy for addiction due to the unprecedented effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. The secondary aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of an online group psychotherapy programme for addiction.

Methods: The Treatment Outcomes Profile (TOPS) was used to assess service user treatment outcomes and abstinence, as well as PHQ9 and GAD7 scores where obtained.

Results: 90% of service users (SU) were discharged as drug and alcohol free upon completion of the programme. 60% of SU completed psychometric outcome data with both PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores showing a statistically significant decrease from baseline scores.

Conclusion: The results indicate good potential for a virtual group programme delivering online psychotherapy for addiction.

Keywords: Substance abuse; Addiction; Behavioural group therapy; Online therapy; Psychotherapy outcome

Introduction

Online therapies can include structured therapy content or interventions that are electronically delivered. These predominantly use videoconferences or email to overcome the distance between a therapist and patient to support, or instead of, face-to-face therapy. The increased acceptance and permeation of computer technology into everyday life has led to the rise of electronic therapy, providing a mechanism that could be used as an early intervention or as an adjunct to existing treatments [1]. This allows patients to access treatment at their convenience and, for some individuals, computers may be more acceptable than traditional face-to-face therapy. Indeed, remote psychotherapy has been considered as a suitable early intervention in a stepped- care model, as it currently functions in the UK National Health Service (NHS). There is also an economic argument for electronic modalities, with evidence that this form of therapy saves both financial cost and are more timeefficient for the therapist [2].

Research has assessed the effectiveness of remote psychotherapy for treating psychiatric disorders including anxiety, depression, and alcohol abuse [3-5]. Such research has found that internet-delivered treatments have been shown to be effective in the treatment of depression and anxiety in adults, achieving similar outcomes as face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) [3], such that it is now recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for the treatment of depression [6]. For example, programs such as “Beating the Blues” [2] have been introduced in adult primary care services in the United Kingdom.

However, research on electronic therapies has rarely documented or explored treatment for addiction and substance misuse, but there is promising initial evidence. One example [7], found the number needed to treat (NNT) was 1.8 for telephonebased support in alcohol misuse, demonstrating a good level of efficacy for remote therapy. Furthermore, McKay [8] found that telephone-based modality produced superior. Outcomes compared to standard 12-step group counselling in all measures examined. However, both pieces of data pertain only to telephone-based support, rather than the inclusion of computer-based support (e.g. email) and videoconferencing software (e.g. Zoom).

The first cases of the Sars-Cov-2 virus (Covid-19) were recorded in late 2019, with the World Health Organization declaring a pandemic, with exponentially increasing cases spreading globally, by March 12th, 2020 [9]. Consequently, group therapy was suspended at the RDP due to social distancing and national lockdown measures. Over the space of 48 hours, psychotherapy was now delivered via a virtual programme, with practitioners delivering remote psychotherapy via phone call, text, email and video chat (i.e. Zoom). In this study, we aimed to document this transition by measuring the outcome measures of service users (SU) enrolled on the virtual programme.

Materials and Methods

The Recovery Day Programme (RDP) is a group programme for the treatment of substance misuse disorder. The service is provided by Central and North West London (CNWL) NHS Trust and the Westminster Drug Project (WDP). The clinical commissioning group in Brent, London, provides psychosocial interventions as part of the RDP in line with stepped-care clinical guidelines for addiction issued by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [10] SUs can be referred via their GP; New Beginnings Addiction teams; Social Services as well as the service accepting Self and other service referrals. All SU’s need to be over the age of 18 and abstinent from illicit drugs and alcohol. Those who meet the eligibility criteria above (aged >18 and abstinent) are invited to attend a structured clinical assessment where clinical history and personal information is collected. This lasts around 60 minutes following a standardized form which also includes psychometric questionnaires such as: patient health questionnaire (PHQ9); generalised anxiety and depression (GAD7); and treatment outcomes profile (TOP).

As part of Public Health England’s (PHE) National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS), SU’s attending the RDP consent to their data being collected, stored and used for the purposes of treatment monitoring and research. This consent is obtained at the point of assessment. All SU’s enrolled on the RDP at the time of this research consented to their data being used in accordance with NDTMS. They were given the opportunity to optout of their data being used in the current study, however all SU’s enrolled on the programme gave informed consent.

Group interventions were delivered according to a weekly timetable that repeated every week. Each group was facilitated by a member of staff at the Recovery Day Programme including a Clinical Psychologist, Trainee Psychologists, Assistant Psychologists, Peer support workers and Group Facilitators. All members of staff received standardized training in group facilitation and motivational interviewing techniques for the treatment of substance misuse disorder. The RDP group is a rolling programme, with SU’s joining the group for a period of 12-weeks for 5 days per week, beginning on a Monday and graduating on the Friday of their twelfth week. The programme offered a total of thirteen groups which included a combination of fellowship meetings such as Alcoholic Anonymous and follow-up groups such as Graduates group. The remaining groups were mandatory for all.

The Treatment Outcomes Profile (TOP): A Structured Interview for the Evaluation of Substance Misuse Treatment form [11] is the national outcome monitoring tool for substance misuse services and is completed by all individuals enrolled in treatment for drug and alcohol misuse in the United Kingdom. The form is completed at the start of treatment and upon completion of treatment at the RDP (i.e.12 weeks thereafter). The top form is divided into four categories: substance misuse, injecting risk behaviour, criminal activity, and health and social functioning (see amendment for TOP form). The form is administered via semi-structured interview and quantifies drug and alcohol use in terms of estimated quantity over the preceding 28 days [12].

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalised Anxiety and Depression-7 (GAD-7) baseline scores were taken at assessment prior to enrollment on the group programme. Indeed, routine monitoring of symptoms and reporting of outcomes can improve the quality and effectiveness of psychological care [13] and, as such, the use of routine monitoring of symptoms and reporting of outcomes has also been applied to the internetdelivery of psychological treatment [5]. The PHQ-9 consists of nine items measuring symptoms and severity of depression. It has good internal consistency and is sensitive to change [14]. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0-3 with increasing scores indicating greater symptom severity. Total scores range from 0-27 with a score of 10 or more indicating clinical significance of depressive symptomatology [15] consistent with DSM-V symptoms for major depressive disorder (DSM-V, 2014). The GAD-7 consists of seven items measuring the presence of symptoms of generalized anxiety, social phobia and panic disorder [16]. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 to 3 with increasing scores indicating greater symptom severity. Total scores rate from 0 to 21 with a score of 8 or more indicating clinical significance of anxious symptomatology [16]. The GAD-7 has good internal consistency and good validity with other anxiety and disability scales [14].

Results and Discussion

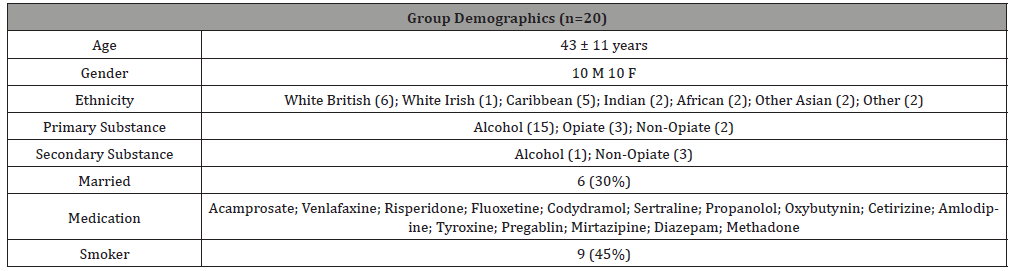

The change to a virtual programme was made on Monday 16th March 2020 due to social distancing and national lockdown measures. Between the period of 16th March 2020 to 5th June 2020 (12 weeks duration), there was a total of 20 SU’s enrolled on the programme. Due to the unprecedented change in structure and function of the National Health Service due to the Covid-19 pandemic, this research was conducted concurrently with such changes and a period of 12 weeks was deemed an accurate snapshot. All 20 SU’s agreed for their data to be used in the research being conducted. There was an even gender split of 10 females and 10 males enrolled on the RDP with an average age of 43 ± 11 years (Table 1). The RDP enrolls SU’s according to the primary substance of misuse which is classified according to these categories: Alcohol (A), Opiate (O), non-opiate (NO), combination of alcohol and nonopiates (ANO).

Table 1:Service user demographics.

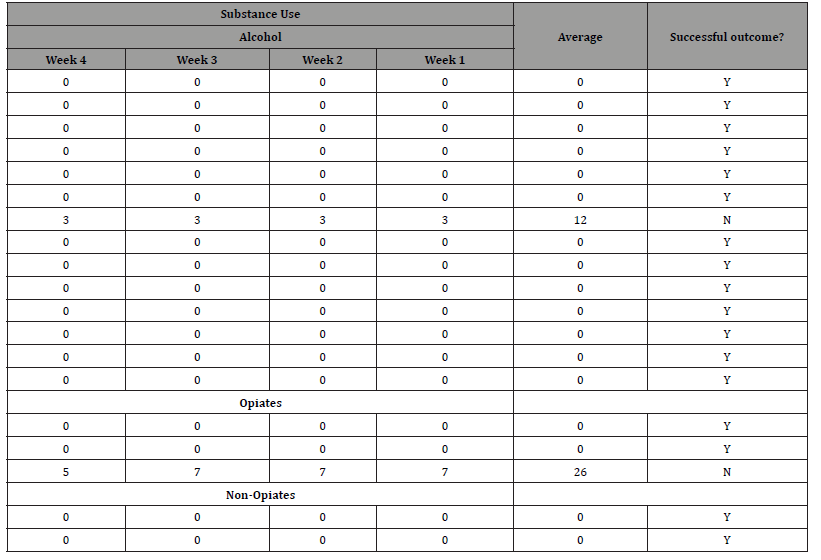

Table 2:Treatment Outcome Profile (TOP) substance use divided by substance covering the penultimate 4 weeks of treatment. Successful treatment delineated as no consumption.

Secondary substances, where applicable, are also collected according to this categorisation. Fifteen SU’s primary substance was alcohol; three SU’s primary substance was Opiates; and two SU’s primary substance was non-opiates. A total of 4 SU’s reported a secondary problem substance, of which one was alcohol, and three were non-opiates. Nine (45%) clients reported themselves as smokers.

Due to comorbid difficulties within the clinical presentation of substance misuse disorder, many SU’s were also taking prescribed medication whilst attending the RDP. For full details of these medications please see Table 1.

As research was conducted concurrently with the shift to a virtual programme, baseline data was retrospective, pertaining to the SU’s completed clinical assessment. These were then readministered upon completion of the RDP 12 weeks later. All 20 (100%) SU’s completed the TOP at baseline and follow-up. 18 (90%) of SU scored 0 on the substance misuse domain. 80% of SU were therefore discharged as drug and alcohol free (i.e. successful completion of the programme).

Fifteen SU’s from the cohort had baseline PHQ-9 scores recorded with 9 (60%) having follow-up PHQ-9 scores. The average PHQ-9 score at baseline was 10.6 (±5.6) with the average PHQ-9 score upon completion of 12 weeks was 2.4 (±3.4). A score of less than 5 is deemed to represent remission [14]. There was a mean change of -8.2 (95% CI: -12.6, -3.8, p-value <0.003) in PHQ-9 scores, with previous research suggesting a 5-point change in scores to be clinically significant [15]. Fifteen SU’s from the cohort had baseline GAD-7 scores recorded with 9 (60%) patients having follow-up GAD-7 scores. The average GAD-7 score at baseline was 9.7 (± 6.5) and the average GAD-7 score upon completion of 12 weeks was 1.5 (±1.4) with a mean change of -8.2 (95% CI: -13.0, -3.5, p-value <0.004). A score of less than 8 is deemed to not be clinically significant [16].

Conclusion

The Recovery Day Programme is a group psychotherapy for addiction programme that is aimed at helping SU’s to maintain their abstinence and develop psychological skills to assist them in their recovery. This research demonstrates the initial outcome measures for an adapted version of the programme which was delivered through a combination of video conferencing platforms (e.g. Zoom), email, text and telephone formats. 90% of service users completed the 12-week programme and were able to maintain their abstinence during this time. Furthermore, there was a statistically significant decrease in psychometric outcome measures upon completion compared to baseline scores. This preliminary evidence therefore supports the transition to virtual psychotherapy for addiction, suggesting good outcomes.

It is key that future research and clinical practice considers the careful implementation of such technology. Indeed, characteristic of substance misuse disorder is a loss of social and economic capital, therefore meaning that the individuals seeking treatment may not have access to such forms of technology. This may limit the future scope of virtual psychotherapy for addiction. It is also worth considering that the primary aim of the change to a virtual modality here was because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Therefore, the findings here may well be limited to such extreme and individual circumstances. It is likely that with much more preparation and planning, the outcome measures may well be improved upon. On the other hand, with the option of face-to-face therapy, SU’s may disengage with the virtual formats. Indeed, the research literature focusing on internet-delivered psychotherapy has often been administered with the aim of examining the costeffectiveness or to reduce the time burden for professionals. For these reasons, the findings should be taken as encouragement for a virtual format, but with caution not to displace the value that faceto- face psychotherapy can provide.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- Spence SH, Holmes JM, March S, Lipp OV (2006) The feasibility and outcome of clinic plus internet delivery of cognitive-behavior therapy for childhood anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol 74(3): 614-621.

- McCrone P, Knapp M, Proudfoot J, Ryden C, Cavanagh K, et al. (2004) Cost-effectiveness of computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy for anxiety and depression in primary care: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 185: 55-62.

- Andersson G (2009) Using the Internet to provide cognitive behaviour therapy. Behav Res Ther 47(3): 175-180.

- Craske MG, Rose RD, Lang A, Welch SS, Campbell‐Sills L, et al. (2009) Computer‐assisted delivery of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in primary‐care settings. Depress Anxiety 26(3): 235-242.

- Titov N (2007) Status of computerized cognitive behavioural therapy for adults. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 41(2): 95-114.

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (2006) Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for depression and anxiety.

- Wongpakaran T, Petcharaj K, Wongpakaran N, Sombatmai S, Boripuntakul T, et al. (2011) The effect of telephone-based intervention (TBI) in alcohol abusers: a pilot study. J Med Assoc Thai 94(7), 849-856.

- McKay JR, Lynch KG, Shepard DS, Ratichek S, Morrison R, et al. (2004) The effectiveness of telephone-based continuing care in the clinical management of alcohol and cocaine use disorders: 12-month outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol 72(6): 967-979.

- World Health Organization (2020).

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (2016) Coexisting severe mental illness and substance misuse: community health and social care services.

- Marsden J, Farrell M, Bradbury C, Dale‐Perera A, Eastwood B, et al. (2008) Development of the treatment outcomes profile. Addiction, 103(9): 1450-1460.

- Luty J, Varughese S, Easow J (2009) Criminally invalid: the treatment outcome profile form for substance misuse. Psychiatric Bulletin 33(11): 404-406.

- Clark DM, Canvin L, Green J, Layard R, Pilling S, et al. (2018) Transparency about the outcomes of mental health services (IAPT approach): an analysis of public data. The Lancet 391(10121): 679-686.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B (2010) The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 32(4): 345-359.

- Kroenke K (2012) Enhancing the clinical utility of depression screening. CMAJ 184(3), 281-282.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JW, Löwe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med, 166(10): 1092–1097.

-

Leah Orme, Andre Geel C. Online Group Psychotherapy for Addiction During Covid-19. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 4(3): 2021. OAJAP.MS.ID.000588.

Substance abuse, Behavioural group therapy, Electronic therapy, Online therapy, Psychotherapy outcome, Face-to-face therapy, Alcohol abuse, Opiate, Non-opiate, Depressive symptomatology

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.