Research Article

Research Article

Finding Hope During a Pandemic: Remembering Moments of Joy

Karin Richards1*, Barbara Kellar2 and Dominique Dietz2

1Department of Kinesiology, University of the Sciences, USA

2Department of Physical Therapy, University of the Sciences, USA

Karin Richards, Department of Kinesiology, University of the Sciences, USA.

Received Date: March 01, 2021; Published Date: April 6, 2021

Abstract

The purpose of the study was to assess hope during the COVID-19 pandemic in students enrolled a healthcare-focused university. A total of 63 university students, (ages 18 >) participated in the cross-sectional study and completed a 12-item, Likert scale questionnaire. A repeated measures analysis of variance was conducted to determine if there were differences in the constructs of temporality and future; positive readiness and expectancy; and interconnectedness in the overall sample. There were significant differences in the levels of the constructs. Pairwise comparisons revealed that positive readiness and expectancy scores were significantly higher than the other constructs. More than six months into the COVID-19 pandemic, hope towards the future and connection with others was floundering. Yet aspiring healthcare students were still able to persevere by discovering opportunities despite challenges, remembering pleasant experiences, and feeling grateful for their lives. Building on these strengths may benefit not just students, but also instructors and future patients.

Keywords:Hope; Pandemic; Anxiety; Positive readiness; Expectancy

Introduction

The concerning mental health aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic, some presenting as worry, stress, anxiety, depression, and even suicide, are well documented in the literature [1-4]. During the initial COVID-19 lockdown in France, it was suggested that over 18,000 university students experienced a high level of anxiety, while close to 8,000 university students contemplated suicide [3]. Nearly half of these 69,054 individuals surveyed were firstyear students [3]. In China, students added financial impacts and academic challenges as anxiety-inducing concerns [4]. Similarly, students in the United States further identified inattentiveness, loneliness, and sleep disturbances as additional effects stemming from the pandemic, particularly due to social distancing and subsequent lockdowns [1,2]. With multiple studies focused upon what is detrimental to students’ mental health and the pandemic, this study sought to explore what is giving students hope during this trying time [1-4]. Hope has been explained as belief in oneself and the future; as well as a multifaceted of confidence, planning, and action with higher levels of hope positively associated with reduced anxiety, depression, and overall wellness. [5-8]. Evaluating levels of hope, therefore, may provide insight to instructors into not just what areas are in most need of attention and may warrant a referral to a healthcare professional, but those points of strength to further build upon [5].

Materials and Methods

A convenience sample of undergraduate students (n= 63) completed the Hope Herth Index, a 12-item Likert scale assessment tool, evaluating individual and group levels of hope [9]. Composite scores were computed for the constructs of temporality and future; positive readiness and expectancy; and interconnectedness by summing the items corresponding to each construct. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 26) was utilized in conducting a MANOVA to determine if there were differences among classes, (freshman, junior, and senior), of students, on the constructs. An ANOVA was also conducted to determine if there were differences in constructs in the overall sample.

Result and Discussion

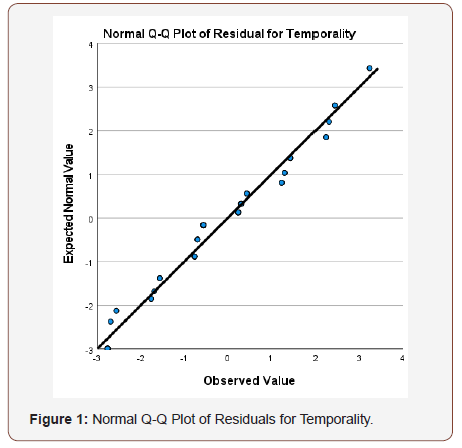

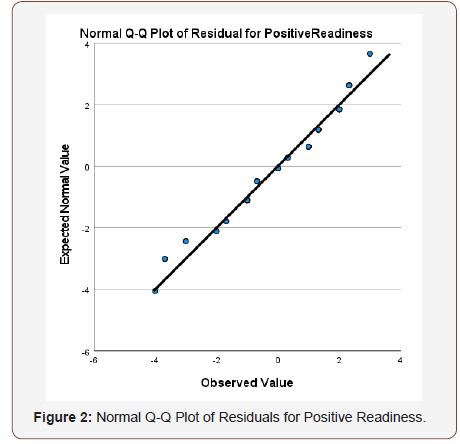

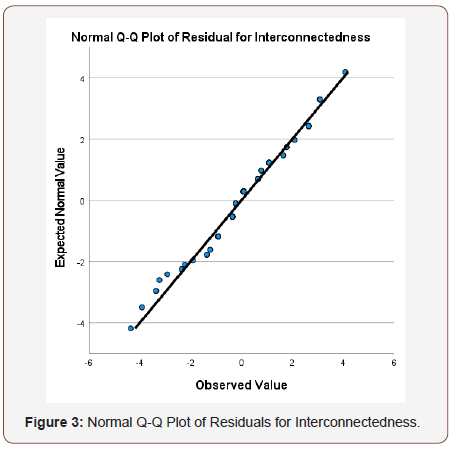

Composite scores were computed for the constructs of temporality, positive readiness, and interconnectedness by summing the items corresponding to each construct. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to determine if there were differences between classes (freshman, junior, and senior) on the measures of temporality, positive readiness, and interconnectedness. Normality was assessed by inspection of normal Q-Q plots of the residuals for each dependent variable (Figures 1-3); there was little deviation from the normal line, indicating that the assumption of normality was met. Homogeneity of variance and covariance were assessed through Levene’s tests and Box’s M test respectively; these tests were not significant (all p-values > .05), indicating that the assumptions were met. The Pillai’s Trace multivariate test for class was not significant, F(6,118) = 1.14, p = .344, indicating that there were no significant differences between freshman, juniors, and seniors on the measures of temporality, positive readiness, and interconnectedness.

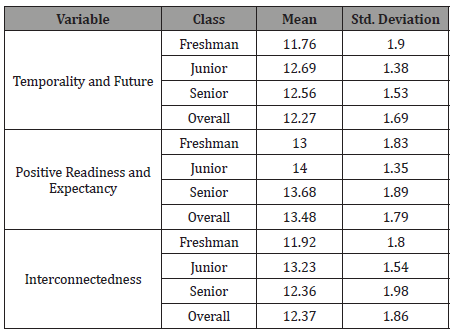

The Pillai’s Trace multivariate test for class indicated that there were no significant differences among freshman, juniors, and seniors on the constructs, F(6,118)=1.14, p=.344. Results of the ANOVA were significant, F(2,124) = 29.12, p < .001, indicating that there were differences in the levels of temporality and future; positive readiness and expectancy; and interconnectedness. Pairwise comparisons revealed that positive readiness and expectancy scores (M = 13.48, SD = 1.79) were significantly higher than temporality and future (M = 12.27, SD = 1.69, p < .001) and interconnectedness scores (M = 12.37, SD = 1.86, p < .001).

With no prior experience of international pandemics, most college students were inadequately equipped to handle the stressors and abrupt lifestyle changes of COVID-19, yet the subjects indicated they were able to find opportunities in challenging situations; remember pleasant experiences; have a planned course, and appreciation for their lives. However, when answering items regarding the future as well as connecting to others, the students scored lower in levels of hope. Studies suggest age is a factor in building greater amounts of hope while interconnectedness has also been suggested to be vital in progressing through the age transition [8-11]. Neither of these factors was evident in our results. Primary limitations of the study include online self-reported measures thus interpretation of item meanings may have caused confusion among participants, limited sample size, and inability to generalize the results to the larger population. Future research should include the evaluation of teaching hope interventions in a virtual and oncampus classroom setting including age, gender, and academic year measures and outcomes in both high school and collegiate institutions

(Table 1).

Table 1:Descriptive Statistics for Three Constructs by Class.

Conclusion

More than six months into the COVID-19 pandemic, hope towards the future and connection with others was floundering. Yet students were still able to persevere by discovering opportunities despite challenges, remembering pleasant experiences, and feeling grateful for their lives. Perhaps this is where instructors should pivot in their courses. Rather than solely focusing on the boosting those areas of low levels of hope; incorporating gratitude, positive outlooks and seeing the potential in difficult times may help to balance the hope of instructors, students and future patients.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the descriptive analytic efforts of Rayyan Ibrahim and Stephanie Noel as well as the statistical analysis of David Kovaz of Statistics Solutions.

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this publication declare no financial, personal or other conflict of interest to this work.

References

- Changwon Son, Sudeep Hegde, Alec Smith, Xiaomei Wang, Farzan Sasangohar (2020) Effects of covid-19 on college students' mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. J Med Internet Res 22(9): e21279.

- Matthew HEM Browning, Lincoln R Larson, Iryna Sharaievska, Alessandro Rigolon, Olivia McAnirlin, et al. (2021) Psychological impacts from COVID-19 among university students: Risk factors across seven states in the United States. PLoS One 16(1): e0245327.

- Marielle Wathelet, Stéphane Duhem, Guillaume Vaiva (2020) Factors associated with mental health disorders among university students in France confined during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 3(10): e2025591.

- Wenjun Cao, Ziwei Fang, Guoqiang Hou, Mei Han, Xinrong Xu, et al. (2020) The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res 287: 112934.

- Jenny M Y Huen, Brian Y T Ip, Samuel M Y Ho, Paul S F Yip (2015) Hope and Hopelessness: The Role of Hope in Buffering the Impact of Hopelessness on Suicidal Ideation. PloS one, 10(6): e0130073.

- Snyder CR (1994) The psychology of hope: You can age there from here. Simon and Schuster: New York.

- Goetzke K (2020) The biggest little book about hope. Innovative Analysis, LLC.

- Caycho T, Castilla H, Ventura León JL (2016) Hope in teenagers and young Peruvian: Differences by sex and age. Psychologia Avances de la Disciplina 10(2): 33-41.

- K Herth (1992) Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: development and psychometric evaluation. J Adv Nurs 17(10): 1251-1259.

- Sandra Yu Rueger, Christine Kerres Malecki, Michelle Kilpatrick Demaray (2010) Relationship between multiple sources of perceived social support and psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence: Comparisons across gender. J Youth Adolesc 39(1): 47-61.

- Ming Te Wang, Jacquelynne S Eccles (2012) Social support matters: Longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Dev 83(3): 877-95.

-

Karin Richards, Barbara Kellar, Dominique Dietz. Finding Hope During a Pandemic: Remembering Moments of Joy. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 4(4): 2021. OAJAP.MS.ID.000591.

COVID-19; Hope; Pandemic; Anxiety; Positive readiness; Expectancy; Anxiety, Depression, Wellness; Healthcare professional; Future patients

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.