Review Article

Review Article

Facebooking by Adolescents: A Narrative Review

Tiffany Field*

University of Miami/Miller School of Medicine, Fielding Graduate University, USA

Tiffany Field, University of Miami/Miller School of Medicine, Fielding Graduate University, USA.

Received Date: March 06, 2020; Published Date: March 31, 2020

Abstract

Facebook, as the world’s most popular social networking site, is serving approximately 2 billion people including 92% of adolescents who are online daily. This narrative review includes published research from the last decade on the use and misuse of Facebook by adolescents. The research on Facebook use has focused on motives for its use, which have been primarily for companionship and relationship maintenance. In turn, online relationships have facilitated or debilitated offline relationships. The Facebook misuse research, also called Facebook addiction research, includes prevalence data, Facebook addiction scales, the effects of and the risk factors for Facebook addiction. The effects have included negative behaviors online and negative relationship outcomes. The risk factors have included intense Facebook usage, fear of missing out, mood states (loneliness, stress, depression and anxiety) and personality factors (extraversion and narcissism). Since most of the research has been cross-sectional, direction of effects cannot be determined. This literature is also limited by the almost exclusive use of self-report measures. Nonetheless, the research highlights the problematic use of Facebook by adolescents.

Introduction

A review on Facebook addiction in adolescents revealed that as of the beginning of 2014, there were 1.28 billion active users on the site per month and at least 802 million of these users logged onto Facebook daily [1]. By 2017 there were at least 2 billion users, making Facebook the most popular social networking site in the world [2]. In a recent study on 1534 Italian students, 86% were using Facebook [3]. And in another recent study, 92% of adolescents were on Facebook daily. This widespread use of social networking sites like Facebook has contributed to some negative side effects for adolescents including internet addiction, cyberbullying, sexting, gaming addiction [4-7] and more recently Facebook addiction. The methods for this narrative review on Facebook use and misuse involved literature searches on PubMed, PsycINFO, Science Direct, ProQuest and FAST for publications from the last decade. The search terms included Facebook, Facebook use, Facebook misuse, Facebook addiction. Exclusion criteria included case studies, nonjuried and non-English publications (Table 1).

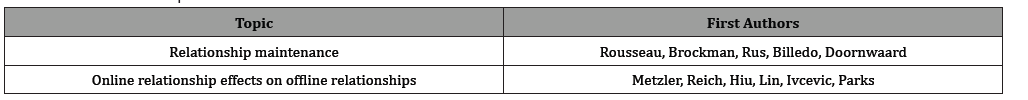

Table 1:Facebook use topics and first authors.

The research on Facebook use has focused on motives for its use, which have been primarily for companionship and relationship maintenance, and on associations between online and off-line relationships which include how online relationships have facilitated or debilitated off-line relationships. The Facebook misuse research, also called Facebook addiction research, includes prevalence data, Facebook addiction scales, the effects of and the risk factors for Facebook addiction. The effects have been mostly negative including negative behaviors online and negative relationship outcomes. The risk factors/predictors have included intense Facebook usage, fear of missing out, mood states (loneliness, stress, depression and anxiety) and personality factors (extraversion and narcissism). Since most of the research has been cross-sectional (not longitudinal), causality or direction of effects cannot be determined, although the authors of the correlation studies have labeled these effects and risk factors accordingly. This literature is also limited by the almost exclusive use of self-report measures. Nonetheless, the research highlights the problematic use of Facebook by adolescents. This review is accordingly divided into sections on the motives for Facebook use, on the prevalence of Facebook addiction and its effects and risk factors and on methodological limitations of the literature (Tables 2&3).

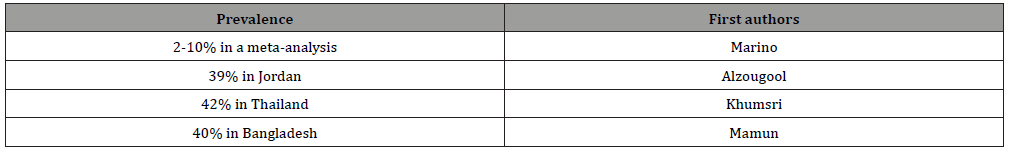

Table 2:Facebook addiction prevalence and first authors.

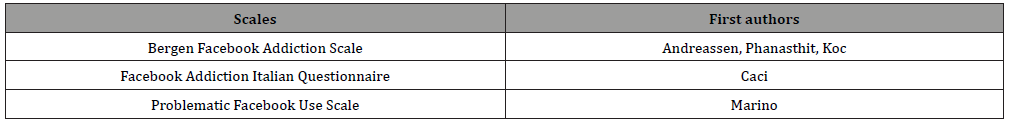

Table 3:Facebook use topics and first authors.

Facebook Use

The most popular motives for Facebook use have included relationship maintenance, passing time, entertainment and companionship. In the 2014 review by Ryan et al, 30% of the 24 studies they reviewed cited relationship maintenance as the primary motive for Facebook use. Both the positive and negative effects of online relationships on offline relationships have also been the focus of many of the recent studies.

Relationship maintenance behavior

In a sample of 1840 12-18-year-old Flemish adolescents, Facebook relationship maintenance behavior and closeness to friends were reciprocally related based on cross-lagged structural equations models using data across a 6-month period [8]. That Facebook relationship maintenance behavior positively predicted adolescents’ closeness to friends and closeness to friends positively predicted Facebook relationship maintenance behavior was not surprising. These data are supported by those from a U.S. study on 338 adolescents, suggesting that over a 12-month period, the online friendship retention rate was as high as 96% [9].

Facebook relationship maintenance behavior has also been studied in romantic relationships and has reportedly served as a maintenance function in at least 26 peer-reviewed articles that were published from 2000 to 2015 and were reviewed in 2017 [10]. These data have typically referred to the maintenance of geographically close romantic relationships, although at least one article was found on participants in long-distance romantic relationships [11]. In this study on 272 young facebook users, long-distance romantic relationships were compared to geographically close relationships for relationship maintenance behaviors. The results suggested that higher levels of relationship maintenance behaviors as well as more partner surveillance behaviors were reported by those in distant relationships. Not surprisingly, romantic references have been used as relationship maintenance behaviors by those in romantic relationships. For example, in a study on 104 Dutch adolescents, 26% of the profiles included romantic references that were predominantly posted by and referred to the profile owner [12].

Unfortunately, all of the relationship maintenance behavior studies in this literature were limited to online relationships. However, some studies were found that assessed the impact of online behavior on offline relationships.

Online behavior effects on offline relationships

The literature on online behavior effects on offline relationships is mixed. At least one study revealed that the initiation of online relationships positively influences the initiation of offline relationships over time [13]. The authors of this longitudinal study on 217 Berlin adolescents concluded that Facebook may be a training ground for enhancing adolescent social skills and relationships. In a study on 251 California high school students, the adolescents were noted to mainly use Facebook to connect with others especially friends they knew offline [14]. These authors suggested that online contacts were used to strengthen offline relationships.

In contrast, in another study on 342 American university students, Facebooking was positively correlated with the students’ psychological well-being via online social relationship satisfaction, but it was negatively linked to psychological well-being through offline social relationship satisfaction [15]. In a qualitative study, the results of a thematic analysis of interviews with high school students (N=204) suggested that they viewed interactive technology as leading to a decline in face-to-face communication in adolescent romantic relationships [16]. And, data from at least two studies are consistent with the students’ interview data. In a study on Taiwanese students, the frequency of Facebook interactions was negatively correlated with offline interactions [17]. Further, in a paper called “Face to (face) book: the two faces of social behavior, Facebook wall pages of 99 students were downloaded six times during three weeks and coded for quantity and quality of Facebook activity [18]. In addition, social interactions were evaluated by self and by friends’ reports. Although the offline interaction behaviors and Facebook behaviors were similar, those students who had more positive offline relationships were less likely to engage in conversations on Facebook.

Mixed media relationships (online combined with offline relationships) are notably complex, as has been noted in a paper entitled “Embracing the challenges and opportunities of mixedmedia relationships” [19]. In this paper, Parks elaborates several of the limitations of research on mixed-media relationships and speaks to the demands of those relationships including “social coordination, impression management, regulating closeness and distance, and managing arousal and anxiety”. Seemingly, it would be difficult to assess mixed-media relationships for these demands given that this recent online/offline literature suggests that adolescents are experiencing a preponderance of either online or offline relationships.

Facebook Addiction

Facebook addiction has been defined by the six criteria of addiction, i.e., salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict and relapse [20]. Other terms denoting Facebook addiction include problematic Facebook use and Facebook intrusion.

Prevalence

Although Marino and his colleagues [21] cited the prevalence of Facebook addiction as ranging between two and 10%, recent studies from various countries have suggested a much greater prevalence. For example, in Jordan, 39% of Facebook users were addicted to Facebook [22]. In this sample of 397 Facebook users, exhibitionism, companionship, escapism and passing time and relationship maintenance were the most significant predictors of Facebook addiction. The prevalence of Facebook addiction amongst Thai adolescents has been slightly higher at 42% [23]. In this sample, everyone hour increase in usage increased the risk for Facebook addiction. A similarly high prevalence has been reported for Bangladeshi students at 40% [24]. In a regression analysis, the risk factors for Facebook addiction were being single, having less involvement in physical activities, sleep disturbance, time spent on Facebook (greater than five hours per day) and depression symptoms.

Facebook addiction scales

Prevalence rates have been based on a few scales that were adapted from other addiction scales. One of the most popular is the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale which initially was a pool of 18 items with three items reflecting each of the core elements of addiction including salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict and relapse [25,26]. In this study, the authors conducted factor analysis and retained an item from each of the six addiction elements for the final Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale. This was based on a sample of 423 students, but it has also been replicated by other groups including a group from Thailand who reported high internal consistency (Cronbach alpha coefficient=91) based on a sample of 874 high school students [27]. In a sample of 447 Turkish students, the construct validity of the Facebook Addiction Scale was further supported [28]. However, the results revealed different predictors including weekly time commitment, social motives, severe depression, anxiety and insomnia. And, no demographic variables were significant predictors. Two other scales have been used including a variant of Young’s Internet Addiction Test that was developed on an Italian sample and is now called the Facebook Addiction Italian Questionnaire [29]. And a third scale called the Problematic Facebook Use Scale was adapted from Caplan’s Generalized Problematic Internet scale based on a sample of 1460 Italian adolescents [30].

The results of these studies are highly variable in terms of the significant predictor variables which likely relates to the different cultures being assessed and the different scales being used. It may also be problematic that the scales are adaptations of scales that were designed for other addictions especially since it is not clear that Facebook addiction is similar to other forms of addiction. Although each of the scales appears to have good psychometric properties based on factor analyses, the scales have not been compared within a single sample. As for many other adolescent social media problems, different scales have been used by different research groups [31]. Finding consensus on the effects and the risk factors for Facebook addiction has been limited by the variability of these assessment tools.

Facebook addiction effects

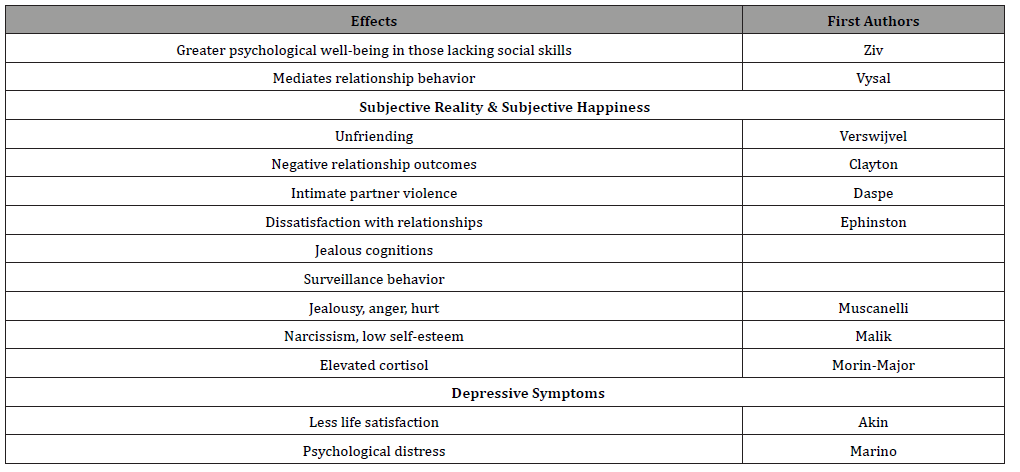

Only twelve studies could be found on the effects of adolescent Facebook addiction in the recent literature. These included both positive and negative effects. The two positive effects studies reported greater psychological well-being for those lacking social skills as well as greater subjective happiness following Facebook addiction. The ten negative effects studies revealed negative behaviors, negative relationship outcomes, aggression, narcissism, low self-esteem, elevated cortisol, low life satisfaction and psychological distress (Table 4).

Table 4:Facebook addiction effects and first authors.

A study on psychological well-being involved 200 Israeli adolescents being given questionnaires that assessed their Facebook use, mental resilience and psychological well-being [32]. The findings suggested that Facebook use was positively correlated with psychological well-being but that this relationship was mediated by low mental resilience, suggesting that excessive Facebook use had positive effects on individuals who lacked social skills. In the study on subjective happiness, 297 were administered scales on Facebook addiction, subjective vitality and subjective happiness [33]. Facebook addiction was shown to mediate the relationship between subjective vitality and subjective happiness.

Negative effects included unfriending and negative relationship outcomes. In a study that examined the reasons for unfriending on Facebook, open-ended questions were given to 419 adolescents [34]. Qualitative analyses suggested that unfriending typically occurred for online reasons such as bragging or stalking; posting too many inappropriate, polarizing or uninteresting posts; and other irritating behaviors such as using bad grammar. The adolescents also unfriended people due to quarrels and incompatibility. Similar results were noted in a survey of 205 Facebook users using a 16-question online survey [35]. Regression analysis indicated that excessive Facebook usage was associated with negative relationship outcomes and that Facebook-related conflict mediated this relationship. In a Canadian study, Facebook jealousy emerged as a significant mediator of the association between Facebook use and intimate partner violence [36].

Data from a few other Facebook studies suggest negative effects of internet addiction on peer relationships. In one study, a Facebook Intrusion Questionnaire was developed based on internet addiction [37]. Facebook intrusion was related to dissatisfaction with peer relationships, to jealous cognitions and to surveillance behaviors. In another Facebook study, research participants were asked to imagine viewing their romantic partner’s Facebook page [38]. The researchers varied the hypothetical privacy settings and the number of the couple photos on Facebook. Negative emotions resulted including jealousy, anger, disgust and hurt, especially for the females who felt these more intensely than the males [39].

Facebook addiction has been a significant predictor of other negative behaviors. In a Pakistan study, Facebook addiction of 200 students was correlated with narcissism and low self-esteem [40]. Surprisingly, Facebook addiction was a significant predictor of narcissism and low self-esteem rather than those personality variables predicting the Facebook addiction. Another surprising funding resulted from a hierarchical regression on data from 88 Canadian adolescents suggesting that elevated cortisol was positively associated with the number of Facebook friends and negatively correlated with Facebook peer-interaction [41]. Also, surprisingly, no associations were noted between cortisol and depressive symptoms.

Given the above negative effects following on excessive Facebook use, it is not surprising that Facebook use has been negatively related to life satisfaction in a study on 370 Turkish students [42]. And, in a meta-analysis of 23 samples (N=13,929 adolescents), problematic Facebook use was correlated with psychological distress, but directionality of effects could not be determined due to the studies being cross-sectional.

Relative to the surprising findings that Facebook addiction has predicted personality traits like narcissism rather than the reverse, it is difficult to determine the directionality of effects from these cross-sectional studies. In results given as correlation coefficients, it is clear that causality is not implied, However, for regression analyses, researchers can arbitrarily treat a variable either as a predictor or an outcome. As noted in the next section on risk factors, narcissism, for example, has typically been treated as a risk factor/predictor variable in several studies rather than an outcome. And, in the next section, it is apparent that four times as many risk factors studies versus effects studies have appeared in the recent literature on Facebook addiction.

Risk Factors for Facebook Addiction

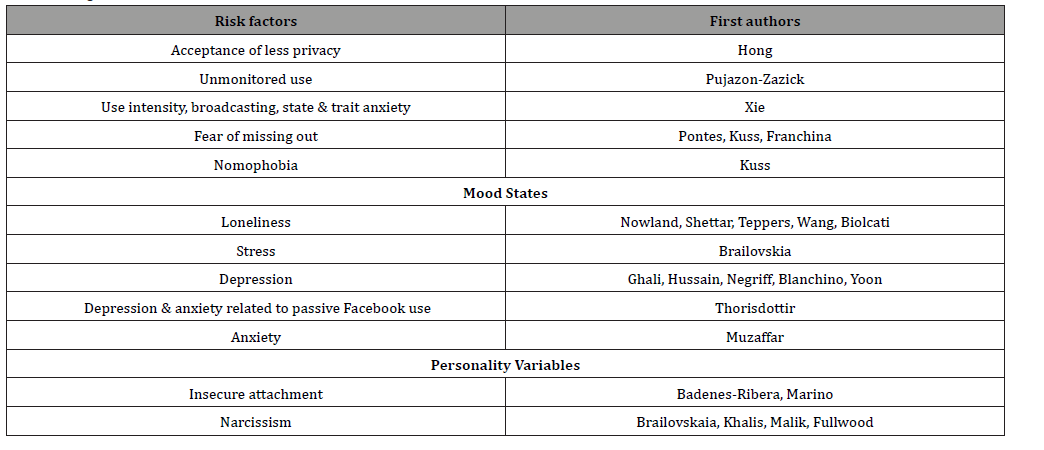

Table 5:Negative risk factors for Facebook addiction and first authors.

Many risk factor studies have appeared in the recent literature on Facebook addiction including excessive usage, unmonitored Internet use, broadcasting, fear of missing out, phubbing (texting while ignoring someone), nomophobia (fear of being without a cell phone), attachment disorders, mood states including loneliness, stress, depression and anxiety and personality factors including insecure attachments to parents and peers, empathetic and perspective-taking behaviors, extraversion and narcissism. The majority of the studies relate to the mood states loneliness and depression and the personality factors extraversion and narcissism (Table 5).

Facebook specific risk factors

A desire for or an acceptance of lower online psychological privacy has correlated with Facebook addiction in a sample of 225 Taiwanese students [43]. Unmonitored Internet use is the second Facebook-related risk factor noted in a study on adolescents in California [44]. In another study from the U.S., Facebook use intensity predicted Facebook addiction as well as Facebook use for broadcasting and state and trait anxiety [45].

In a study from the United Kingdom, fear of missing out (FOMO) made the most significant contribution over and above the effects of sociodemographic variables and patterns of use to Facebook addiction [46]. Another research group from the UK reported that fear of missing out and nomophobia (fear of being without a mobile device) were predictors of Facebook addiction [47]. In a study on 2663 Flemish teenagers, fear of missing out (FOMO) was again the strongest predictor of problematic Facebook use [48]. FOMO, in turn, predicted phubbing behavior (being on a cell phone avoiding someone who is present).

Given these fears of missing out and being without a cell phone predicting Facebook addiction, a research group from Australia conducted a study called “Taking a break: the effect of taking a vacation from Facebook” [49]. Usage amount and style were identified at baseline and users were assigned to a one-week vacation or no vacation from Facebook. Surprisingly, at the posttest following the experimental period, the results showed that the vacation led to lower positive affect for active users but had no effect on passive users. The authors concluded that Facebook can positively affect active users. Mood States. Various mood states have been associated with Facebook addiction. These include loneliness, stress, depression and anxiety. Although these are rarely measured in the same study, they are likely comorbid states that exacerbate the effects typically attributed to a single mood state.

Loneliness

As has been noted, when adolescents do not engage in social interaction or they withdraw from social action, their feelings of loneliness would be expected to increase. Lonely adolescents are noted to use Facebook for social interaction and in that way, they spend less time in offline social interaction [50]. Not surprisingly, those who have studied loneliness Facebook addicted adolescents have revealed strong correlations between Facebook addiction and loneliness. Researchers have typically viewed this as a predictor for the data are typically derived from cross-sectional studies making any assumption of causality tenuous.

In a study on 100 students in India, 26% of the participants had Facebook addiction and 33% were noted to have a “possibility” of Facebook addiction [51]. The results yielded a strong positive correlation between Facebook Addiction scores and scores on the UCLA Loneliness Scale. A cross-lagged analysis on data from 256 adolescents from the Netherlands suggested that peer-related loneliness was related to Facebook use over time for social skills compensation, reducing feeling of feelings of loneliness and having interpersonal contact [52]. When Facebook was used for social skills compensation, peer-related loneliness increased over time. More complex relations were noted in a study on 1188 Belgian adolescents [53]. In this two- wave panel study with a one-year interval, emotional loneliness predicted more active Facebook use among lonely adolescents but not among adolescents who did not feel lonely.

Stress

In in a sample of 309 German Facebook users, daily stress was positively related to the intensity of Facebook use [54]. In this sample, individuals who received low levels of support offline increased their Facebook use at higher levels of daily stress. Facebook use intensity was related to both positive (receiving online social support) and negative (Facebook addiction) effects, thus making individuals who received high levels of social support online at greater risk for Facebook Addiction Disorder. In a study by the same group, but a larger sample from two countries (N = 531 in the German sample and N = 909 in the US sample) [55]. In this sample, daily stress was positively associated with Facebook Addiction Disorder and depression symptoms moderated this relationship. This more complex finding suggests that depressed individuals who tend to extensively use Facebook to escape from daily stress are at enhanced risk to develop Facebook Addiction Disorder.

Depression

At least eight different studies from different countries have reported that depression is a significant risk factor for Facebook addiction, although one study reported no relationship between depression and Facebook addiction. Using an Arabic version of the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale, a group of Tunisian researchers studied the relationship between Facebook addiction and depression in 1399 students of which 28% had Facebook addiction [56]. Students with higher Facebook addiction scores were significantly more depressed and more addicted to video games. In an eye tracking study from the UK, 69 individuals engaged in Facebook sessions while their eye movements and fixations were recorded [57]. Self-reported duration of typical Facebook sessions did not correlate with the eye tracking measures, but Facebook addiction scores were related to depression scores.

In one of the few longitudinal studies, directionality for the depression-Facebook addiction relationship could be determined [58]. Adolescents reported on depressive symptoms at the first assessment (N=319) and at the follow-up assessment an application downloaded the friend list and Facebook use computed (N=133). Based on a path analysis, depression at time one predicted fewer Facebook friends, fewer ties between friends, more components and fewer friends on the main component of the network at time 2. Limitations of this study are the significant attrition and the assumption that depression would predict Facebook addiction. Depression was only assessed at baseline and Facebook usage was only assessed at time 2 rather than assessing both variables at both time periods to determine directionality. In a cross-sectional study from Poland on a sample of 672 Facebook users, the Facebook Intrusion Questionnaire and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale were used [59]. The data showed that depression was a predictor of Facebook intrusion as well as being male, young age and spending an extensive amount of time on Facebook.

In a meta-analysis on Facebook-depression relations, 33 articles on a sample of 15,881Facebook users suggested that depression was related to time spent on Facebook and frequency of checking Facebook [60]. Depressive symptoms have also been a risk factor for peer victimization on Facebook in a sample of 1621 adolescents in Belgium [61]. Despite data from many studies documenting depression as a significant predictor variable for Facebook addiction, at least one study showed no relationship between depression and Facebook addiction [62].

Depression and anxiety

Given that depression and anxiety are typically comorbid, it’s surprising that those two mood states have only been studied together in a few studies. In one of these, active versus passive Facebook use was studied in 10,563 Icelandic adolescents [63]. A hierarchical linear regression revealed that greater depression and anxiety were related to passive Facebook use, while less depression and anxiety were related to active Facebook use. Depressed mood was more strongly related to passive use in girls. Surprisingly, gender differences have rarely been noted in this literature.

In the only study in this literature that measured social anxiety in adolescents as it relates to Facebook use, there was surprisingly no relationship between social anxiety and Facebook use [64]. In this survey on 102 adolescents, greater general anxiety but not social anxiety symptoms were associated with a greater number of Facebook friends and a greater amount of time spent on Facebook.

Personality variables

Personality variables that have been considered predictors of Facebook addiction include insecure attachment, narcissism and presentation of multiple versions of the self-online. Of these, narcissism has been the focus of most of the studies [65].

Insecure attachment

Insecure parent and peer attachments have been considered predictors of Facebook addiction at different developmental stages. In a sample of 598 adolescents from Italy, relationships with parents predicted Facebook addiction in early adolescence including withdrawal, conflict and relapse [66]. For older adolescents, peer relationships including alienation were the most relevant predictors of Facebook addiction. Peer influence was noted in one other study, but here the variable was termed conformity which was the strongest predictor of problematic Facebook use [67].

Narcissism

At least seven studies appeared in the literature on narcissism as a predictor of Facebook addiction with three of the studies being from the same research group in Germany. Other cultures that were represented included Korea, Pakistan, Italy and Canada. In the first of the studies from Germany, Facebook addiction disorder increased across a period of one year in terms of the number of participants reaching the critical cutoff score [68]. Facebook addiction was significantly related to the personality trait narcissism as well as to depression, anxiety and stress symptoms in this sample. In the second study from the same research group, six per cent of the 520 participants reached the critical cutoff score [69]. Once again, Facebook addiction disorder was related to the personality trait narcissism as well as to depression, anxiety and, surprisingly, subjective happiness. The frequency of Facebook uses partially mediated the relationship between narcissism and Facebook addiction disorder. In the most recent study by this research group, the relationship between Facebook addiction disorder and narcissism was studied in an inpatient sample of 112 Facebook users [70]. In this clinical sample, 29% reached the critical cutoff score for Facebook addiction disorder and 87% had withdrawal symptoms due to Facebook use. Once again Facebook addiction disorder was positively linked to the duration of Facebook use and the personality trait narcissism.

In a study from Canada on 240 students, those who displayed a greater quantity of Facebook interactions had more narcissistic selfpresentation on Facebook [71]. In contrast, those who had more face-to-face interactions showed less narcissistic self- presentation on Facebook. In a paper entitled” Why narcissists are at risk for developing Facebook addiction: the need to be admired and the need to belong” [72], a sample of 535 Italian students completed measures of grandiose narcissism, vulnerable narcissism, Facebook addiction and two scales measuring the need for admiration and the need to belong. Structural equations analysis showed an association between grandiose narcissism and Facebook addiction that was mediated by the need for admiration and the need to belong. Vulnerable narcissism was not associated with Facebook addiction. Grandiose narcissism (also called narcissistic grandiosity) has also been a moderator variable in a study showing the relationship between Facebook addiction and social exclusion in Korean students [73]. In a study from Pakistan students, Facebook addiction was positively correlated with narcissism and negatively correlated with self-esteem. In this case the assumed direction of affect was that Facebook addiction was a significant predictor of narcissistic behavior and low self-esteem. Once again there were no significant gender differences on these variables. In a somewhat related study from the UK, adolescents who spend more time on Facebook and had fewer Facebook friends presented multiple versions of themselves while online [74].

These studies, like so many of the risk factor studies, are limited by the focus on one variable. They also typically have made the assumption that negative variables are predicting to Facebook addiction when it is also plausible that Facebook addiction is contributing to negative outcomes as, for example, depression and narcissism. Directionality has been assumed from correlation studies or has been statistically manipulated by using Facebook addiction as an outcome variable in regression and structural equations analyses.

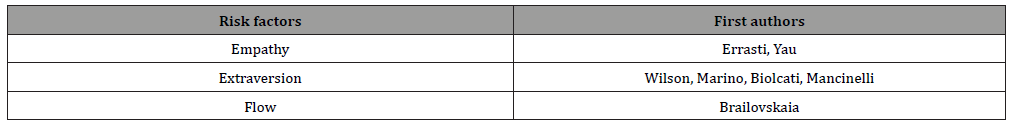

Positive Factors

Most of the predictor variables for Facebook addiction have been considered negative. But some surprisingly positive factors have also been assumed to be predictive of Facebook addiction including empathy, extraversion, and Facebook flow (Table 6).

Table 6:Positive risk factors for Facebook addiction and first authors.

Empathy

In a sample of 503 Spanish adolescents, higher empathy scores were noted for those who used Facebook excessively [75]. In a crosscultural study by the same research group a sample of 479 Spanish adolescence and 405 Thai adolescents were once again assessed for Facebook usage and empathy [76]. The Thai sample was noted to have higher scores on affective empathy but lower scores on cognitive empathy. They also used Facebook more frequently and they engaged in more emotional and empathic expression when using Facebook. Similar data have been presented on California adolescents, although the term perspective taking was used instead of empathy [77].

Extraversion

Extraversion has been noted as a predictor variable for Facebook addiction in at least three different cultures including Italy, Australia and the UK. In the Australian study on 201 students, extraversion predicted greater Facebook use in addition to selfesteem [78]. However, those factors combined did not explain a large amount of variance in Facebook addiction. In a study on 968 Italian adolescents, structural equation modeling showed that extraversion, emotional stability and conscientiousness predicted problematic Facebook use [79]. In another study by a different research group in Italy, 755 students completed the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale, the Big Five Personality Inventory and the Scale for Social and Emotional Loneliness [80].

Based on a regression analysis, extraversion was a significant predictor of Facebook addiction along with conscientiousness, neuroticism and loneliness which would appear to be mixed results. In a systematic review by Italian researchers, nine papers on the Big Five Personality Inventory and Facebook addiction were included in the review [81]. Extraversion was the strongest predictor of Facebook motivation and intensity of use. Facebook flow. Facebook flow was defined by a group of researchers from Germany as “experience of intense enjoyment and pleasure generated by Facebook use due to which the Facebook activity is continued even at high costs of this behavior” [82]. In a sample of 398 Facebook users a set a significant positive association was noted between phase flow and Facebook addiction that was positively moderated by the intensity of Facebook use. The authors suggested that this immersion in Facebook may relate to escaping everyday obligations and problems.

Treating these positive factors including empathy, extraversion and flow as predictors of Facebook addiction and then interpreting them as, for example, an escape from obligations in a sense casts them as negative. It is plausible that an extraverted, empathetic individual may be looking for flow and find it more on Facebook than in the real world and not consider its use problematic.

Potential Underlying Mechanisms

Although no studies in this literature have been labeled potential underlying mechanism studies, in a sense almost any of the predictor and protective factor studies are suggestive of underlying mechanisms such as fear of missing out, trying to curb loneliness, depression, social anxiety, and needing to be admired and to belong. Surprisingly, given the many heart rate variability studies on internet addiction, no studies on this potential mechanism could be found in the recent literature on Facebook addiction. fMRI studies were also found in the Internet addiction literature, but only one fMRI publication appeared in the Facebook addiction literature and that was published several years ago [83]. These authors conducted fMRIs on 20 Facebook users who completed the Facebook addiction questionnaire and responded to Facebook and traffic sign stimuli. Their findings suggested an imbalance of the impulsive (amygdala-striatal) and inhibitory (prefrontal cortex) brain systems, suggesting that Facebook addiction shared neural features with substance and gambling addictions.

Limitations of The Literature and Future Directions

Several of the methodological limitations of the recent Internet addiction literature also apply to this recent literature on Facebook addiction in adolescents. Survey studies on the prevalence, effects and risk factors comprise most of the recent literature on Facebook addiction in adolescents. Virtually no intervention studies were found in this recent literature. Methodological limitations of the research include the lack of a standard Facebook addiction classification and on the reliance on self-report scales that often do not include time spent on Facebook or the particular venues that are being used on Facebook. Smaller sample observation and laboratory studies are needed to explore specific Facebook activities and the risk factors associated with Facebook addiction in adolescents. For example, one of the most notable missing topics from this literature is the social anxiety that might be a risk factor for Facebook addiction. In addition, most of the recent studies are cross-sectional so that causality or direction of effects cannot be determined. Many of the risk factors and effects appear to be correlated as in bidirectional relationships but when regressions are conducted to control for confounding variables and to assess the relative contribution of predictor variables, researchers have arbitrarily designated effects and risk factor variables. In the regression model, direction of effects has been assumed rather than highlighting the variables as having bidirectional relationships. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine causality as well as risk profiles.

Given that Facebook addiction is associated with other demographic, psychological and behavioral variables as well as comorbid addictions multivariate research using structural equation modeling could help identify the relative variance explained by these variables. Profile analysis could inform clinical interventions. It’s not clear why interventions for Facebook addiction haven’t been conducted especially since several interventions have been effective with other adolescent addictions. These could be tried with adolescents experiencing Facebook addiction. Protocols, for example the “parent monitoring and restricting usage” program as well as cognitive behavior therapy, meditation and exercise programs have been effective with other adolescent edition addictions. In addition, given that other comorbid addictions are prevalent (Internet addiction, cell phone addiction, sexting, cyberbullying and substance use), the comorbidities need to be studied in the same sample. And given that these addictions occur as early as pre-adolescence, school-based interventions might be needed for both the students and parents as well as teacher and peer monitoring of addictive behaviors.

Unfortunately, although Internet technology was intended for communication and educational purposes, it has become problematic for adolescent health and well-being. The survey studies that have been reviewed here highlight the prevalence, effects and risks of Facebook addiction. Smaller scale empirical studies are needed to explore the specific Facebook and related addiction behaviors as well as the non-Facebook activities of the addicted adolescents and the underlying risk factors that may help inform the very needed prevention/intervention studies.

Acknowledgement

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of Interest.

References

- Ryan T, Chester A, Reece J, Xenos S (2014) The uses and abuses of Facebook: A review of Facebook addiction. J Behav Addict 3(3): 133-148.

- Morry MM, Sucharyna TA, Petty SK (2018) Relationship social comparisons: Your facebook page affects my relationship and personal well-being. Computers in Human Behavior 83: 140-167.

- Vismara MFM, Toaff J, Pulvirenti G, Settanni C, Colao E, et al. (2017) Internet use and access, behavior, cyberbullying, and grooming:Results of a whole city survey of adolescents. Interact J Med Res 6(2): e9.

- Field T (2018) Cyberbullying: A Narrative Review. Journal of Addiction Therapy and Research 2: 10-27.

- Field T (2018) Internet Addiction in Adolescents: A Review. Journal of Addictions and Therapies 1: 1-11.

- Field T (2019) Adolescent Internet Gaming Addiction: A Narrative Review. Journal of Addiction and Adolescent Behavior 2: 1-10.

- Field T (2019) Adolescent Sexting: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Psychological Research and Reviews.

- Rousseau A, Frison E, Eggermont S (2019) The reciprocal revelations between facebook relationship maintenance behaviors and adolescents’ closeness to friends. Journal of Adolescence 76: 173-184.

- Brockman LN, Christakis DA, Moreno MA (2014) Friending adolescents on social networking websites: A feasible research tool. Journal of Interactive Science 2(1).

- Rus HM, Tiemensma J (2017) “It’s complicated.” A systematic review of associations between social network site use and romantic relationships. Computers in Human Behavior 75: 684-703.

- Billedo CJ, Kerkhof P, Finkenauer C (2015) The use of social networking sites for relationship maintenance in long-distance and geographically close romantic relationships. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 18: 152-157.

- Doornwaard SM, Moreno MA, van den Eijnden RJ, Vanwesenbeeck I, Ter Bogt TF (2014) Young adolescents’ sexual and romantic reference displays on Facebook. J Adolesc Health 55(4): 535-541.

- Metzler A, Scheithauer H (2017) The long-term benefits of positive self-presentation via profile pictures, number of friends and the initiation of relationships on Facebook for adolescents’ self-esteem and the initiation of offline relationships. Front Psychol 8: 1981.

- Reich SM, Subrahmanyam K, Espinoza G (2012) Friending, IMing, and hanging out face-to-face: Overlap in adolescents’ online and offline social networks. Dev Psychol 48(2): 356-368.

- Hu X, Kim A, Siwek N, Wilder D (2017) The Facebook paradox: Effects of Faacebooking on individuals’ social relationships and psychological well-being. Front Psychol 8: 87.

- Vaterlaus JM, Tulane S, Porter BD, Beckert TE (2018) The perceived influence of media and technology on adolescent romantic relationships. Journal of Adolescent Research 33: 651-671.

- Lin JH (2015) The role of attachment style in Facebook use and social capital: Evidence from university students and a national sample. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 18(3): 173-180.

- Ivcevic Z, Ambady N (2013) Face to (face)book: The two faces of social behavior? J Pers 81(3): 290-301.

- Parks MR (2017) Embracing the challenges and opportunities of mixed-media relationships. Human Communication Research 43: 505-517.

- Marino C, Gini G, Vieno A, Spada MM (2018) The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 226: 274-281.

- Marino C, Mazzieri E, Caselli G, Vieno A, Spada MM (2018) Motives to use Facebbok and problematic Facebook use in adolescents. J Behav Addict 7(2): 276-283.

- Alzougool B (2018) The impact of motives for Facebook use on Facebook addiction among ordinary users in Jordan. Int J Soc Psychiatry 64(6): 528-535.

- Khumsri J, Yingyuen R, Manwong M, Hanprathet N, Phanasathit M (2015) Prevalence of Facebook addiction and related factors among Thai High school Students. J Med Assoc Thai 3: 51-60.

- Mamun MAA, Griffiths MD (2019) The association between Facebook addiction and depression: A pilot survey study among Bangladeshi students. Psychiatry Research 271: 628-633.

- Andreassen CS, Pallesen S (2014) Social network site addiction-An overview. Curr Pharm Des 20(25): 4053-4061.

- Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, Pallesen S (2012) Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychol Rep 110(2): 501-517.

- Phanasathit M, Manwong M, Hanprathet N, Kumsri J, Yinyuen R (2015) Validation of the Thai version of Bergen Facebook addiction scale (Thai-BFAS). J Med Assoc Thai 98(Suppl 2): S108-S117.

- Koc M, Gulyagci S (2013) Facebook addiction among Turkish college students: The role of Psychological health, demographic, and usage characteristics. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 16(4): 279-284.

- Caci B, Cardaci M, Scrima F, Tabacchi ME (2017) The dimensions of Facebook addiction as measured by Facebook addiction Italian questionnaire and their relationships with individual differences. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 20(4): 251-258.

- Marino C, Vieno A, Altoe G, Spada MM (2017) Factorial validity of the problematic Facebook use scale for adolescents and young adults. J Behav Addict 6(1): 5-10.

- Escobar-Viera CG, Whitfield DL, Wessel CB, Shensa A, Sidani JE, et al. (2018) For better or worse? A systematic review of the evidence on social media use and depression among lesbian, gay, and bisexual minorities. JMIR Ment Health 5(3): e10496.

- Ziv I, Kiasi M (2016) Facebook’s contribution to well-being among adolescent and young adults as a function of mental resilience. J Psychol 150(4): 527-541.

- Uysal R, Satici SA, Akin A (2013) Mediating effect of Facebook addiction on the relationship between subjective vitality and subjective happiness. Psychol Rep 113(3): 948-953.

- Verswijvel K, Heirman W, Hardies K, Walrave M (2018) Adolescents’ reasons to unfriend on Facebook. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 21(10): 603-610.

- Clayton R, Nagurney A, Smith JR (2013) Cheating, breakup, and divorce: Is Facebook use to blame? Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 16(10): 717-720.

- Daspe ME, Vaillancourt-Morel MP, Lussier Y, Sabourin S (2018) Facebook use, facebook jealousy, and intimate partner violence perpetration. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 21(9): 549-555.

- Elphinston RA, Noller P (2011) Time to face it! Facebook intrusion and the implications for romantic Jealosy and relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 14(11): 631-635.

- Muscanell NL, Guadagno RE, Rice L, Murphy S (2013) Don’t make my brown eyes green? An analysis of Facebook use and romantic jealousy. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 16(4): 237-242.

- Yang SY, Fu SH, Chen KL, Hsieh PL, Lin PH (2019) Relationships between depression, Health-related behaviors, and internet addiction in female junior college students. PLoS One 14(8): e0220784.

- Malik S, Khan M (2015) Impact of Facebook addiction on narcissistic behavior and self-esteem among students. J Pak Med Assoc 65(3): 260-263.

- Morin-Major JK, Marin MF, Durand N, Wan N, Juster RP, et al. (2016) Facebook behaviors associated with diurnal cortisol in adolescents: Is befriending stressful? Psychoneuroendocrinology 63: 238-246.

- Akin A, Akin U (2015) The mediating role of social safeness on the relationship between facebook(®) use and life satisfaction. Psychol Rep 117(2): 341-353.

- Hong FY, Chiu SL (2016) Factors influencing Facebook usage and Facebook addictive tendency in university students: The role of online psychological privacy and Facebook usage motivation. Stress Health 32(2): 117-127.

- Pujazon-Zazik M, Park MJ (2010) To tweet, or not to tweet: Gender differences and potential positive and negative outcomes of adolescents’ social internet use. Am J Mens Health 4(1): 77-85.

- Xie W, Karan K (2019) Predicting Facebook addiction and state anxiety without Facebook by gender, trait anxiety, Facebook intensity, and different Facebook activities. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 8(1): 79-87.

- Pontes HM, Taylor M, Stavropoulos V (2018) Beyond “Facebook addiction”: The role of cognitive-related factors and psychiatric distress in social networking site addiction. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 21(4): 240-247.

- Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD (2017) Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(3): E311.

- Franchina V, Vanden Abeele M, van Rooji AJ, Lo Coco G, De Marez, L (2018) Fear of missing out as a predictor of problematic social use and phubbing behavior among Flemish adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(10): E2319.

- Hanley SM, Watt SE, Coventry W (2019) Taking a break: The effect of taking a vacation from Facebook and Instagram on subjective well-being. PLoS One 14(6): e0217743.

- Nowland R, Necka EA, Cacioppo JT (2018) Loneliness and social internet use: Pathways to reconnection in a digital world? Perspect Psychol Sci 13(1): 70-87.

- Shettar M, Karkal R, Kakunje A, Mendonsa RD, Chandran VM (2017) Facebook addiction and loneliness in the post-graduate students of a university in southern India. Int J Soc Psychiatry 63(4): 325-329.

- Teppers E, Luyckx K, Klimstra TA, Goossens L (2014) Loneliness and Facebook motives in adolescence: A longitudinal inquiry into directionality of effect. J Adolesc 37(5): 691-699.

- Wang K, Frison E, Eggermont S, Vandenbosch L (2018) Active public Facebook use and adolescents’ feelings of loneliness: Evidence for a curvilinear relationship. Journal of Adolescence 67: 35-44.

- Brailovskaia J, Rohmann E, Bierhoff HW, Schillack H, Margaf J (2019) The relationship between daily stress, social support and Facebook Addiction Disorder. Psychiatry Res 276: 167-174.

- Brailovskaia J, Velten J, Margaf J (2019) Relationship between daily stress, depression symptoms, and Facebook Addiction Disorder in Germany and in the United States. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 22(9): 610-614.

- Ghali H, Ghammem R, Zammit N, Fredj SB, Ammari F, et al. (2019) Validation of the Arabic version of hte Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale in Tunisian adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health.

- Hussain Z, Simonovic B, Stupple EJN, Austin M (2019) Using eye tracking to explore Facebook use and associations with Facebook addiction, mental well-being, and personality. Behav Sci (Basel) 9(2): E19.

- Negriff S (2019) Depressive symptoms predict characteristics of online social networks. J Adolesc Health 65(1): 101-106.

- Blanchnio A, Przepiorka A, Pantic I (2015) Internet use, Facebook intrusion, and depression: Result of a cross-sectional study. Eur Psychiatry 30(6): 681-684.

- Yoon S, Kleinman M, Mertz J, Brannick M (2019) Is social network site usage related to depression? A meta-analysis of Facebook-depression relations. Journal of Affective Disorders, 248: 65-72.

- Frison E, Subrahmanyam K, Eggermont S (2016) The short-term longitudinal and reciprocal relations between peer victimization on Facebook and adolescents’ well-being. J Youth Adolesc 45(9): 1755-1771.

- Jelenchick LA, Eickhoff JC, Moreno MA (2013) “Facebook depression?” social networking site use and depression in older adolescents. J Adolesc Health 52(1): 128-130.

- Thorisdottir IE, Sigurvinsdottir R, Asgeirsdottir BB, Allegrante JP, Sigfusdottir ID (2019) Active and passive social media use and symptoms of anxiety and depressed mood among Icelandic adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 22(8): 535-542.

- Muzaffar N, Brito EB, Fogel J, Fagan D, Kumar K, et al. (2018) The association of adolescent Facebook behaviors with symptoms of social anxiety, generalized anxiety, and depression. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27(4): 252-260.

- Sherrell RS, Lambie GW (2018) The contribution of attachment and social media practices to relationship development. Journal of Counseling & Development 96(3): 303-315.

- Badenes-Ribera L, Fabris MA, Gastaldi FGM, Prino LE, Longobardi C (2019) Parent and peer attachment as predictors of Facebook addiction symptoms in different developmental stages (early adolescents and adolescents). Addict Behav 95: 226-232.

- Marino C, Marci T, Ferrante L, Altoe G, Vieno A, et al. (2019) Attachment and problematic Facebook use in adolescents: The mediating role of metacognitions. J Behav Addict 8(1): 63-78.

- Brailovskaia J, Margaf J (2017) Facebook Addiction Disorder (FAD) among German students- A longitudinal approach. PLoS One 12(12): e0189719.

- Brailovskaia J, Rohmann E, Bierhoff HW, Margaf J (2018) The brave blue world: Facebook flow and Facebook Addiction Disorder (FAD). PLoS One 13(7): e0201484.

- Brailovskaia J, Margaf J, Kollner V (2019) Addicted to Facebook? Relationship between Facebook addiction Disorder, duration of Facebook use and narcissism in an inpatient sample. Psychiatry Research 273: 52-57.

- Khalis A, Mikami AY (2018) Talking face-to-Facebook: Associations between online social interactions and offline relationships. Computers in Human Behavior 89: 88-97.

- Casale S, Fioravanti G (2018) Why narcissists are at risk for developing Facebook addiction: The need to be admired and the need to belong. Addict Behav 76: 312-318.

- Lim M (2019) Social exclusion, surveillance use, and Facebook addiction: The moderating role of narcissistic grandiosity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(20): E3813.

- Fullwood C, James BM, Chen-Wilson CJ (2016) Self-concept clarity and online self-presentation in adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 19(12): 716-720.

- Errasti J, Amigo I, Villadangos M (2017) Emotional uses of Facebook and Twitter. Psychol Rep: 33294117713496.

- Errasti JM, Amigo Vazquez I, Villadangos M, Moris J (2018) Differences between individualist and collectivist cultures in emotional Facebook usage: Relationship with empathy, self-esteem, and narcissism. Psicothema 30(4): 376-381.

- Yau, J.C. & Reich, S.M. (2019) “It’s just a lot of work”: Adolescents’ self-presentation norms and practices on Facebook and Instagram. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29(1): 196-209.

- Wilson K, Fornasier S, White KM (2010) Psychological predictors of young adults’ use of social networking sites. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 13(2): 173-177.

- Marino C, Vieno A, Pastore M, Albery IP, Frings D, et al. (2016) Modeling the contribution of personality, social identity and social norms to problematic Facebook use in adolescents. Addict Behav 63: 51-56.

- Biolcati R, Mancini G, Pupi V, Mugheddu V (2018) Facebook addiction: Onset predictors. J Clin Med 7(6): E118.

- Mancinelli E, Bassi G, Salcuni S (2019) Predisposing and motivational factors related to social network sites use: Systematic review. JMIR Form Res 3(2): e12248.

- Brailovskaia J, Schillack H, Margaf J (2018) Facebook Addiction Disorder in Germany. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 21(7): 450-456.

- Turel O, He Q, Xue G, Xiao L, Bechara A (2014) Examination of neural systems sub-serving Facebook “addiction”. Psychol Rep 115(3): 675-695.

-

Tiffany Field. Facebooking by Adolescents: A Narrative Review. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 3(4): 2020. OAJAP.MS.ID.000567.

Facebook addiction, Gaming addiction, Internet addiction, Cyberbullying, Sexting, Misuse of Facebook, Facebook use, Facebook misuse, Facebook usage, Young facebook users, Long-distance romantic relationships, Social coordination, Impression management, Regulating closeness, Managing arousal and anxiety, Mood modification, Tolerance, Withdrawal, Conflict, Relapse

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.