Research Article

Research Article

Emotional Intelligence of Incarcerated Populations as Measured by The Rorschach Inkblot Technique

Ashley Ginter1*, Stephen E Berger2, Bina Parekh3 and Albert Miranda4

1Federal Bureau of Prisons, USA

2The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, USA

3The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, USA

4Cultural Neuropsychology Program, Hispanic Neuropsychiatric Center of Excellence, UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, USA

Ashley Ginter, Federal Bureau of Prisons, USA.

Received Date: January 01, 2020; Published Date: January 22, 2020

Abstract

present study was designed to address two specific goals. The first was to analyze the differences between incarcerated and non-incarcerated individuals regarding their scores on specific Rorschach variables that are associated with emotional intelligence (EI). The second was to investigate the differences in scores on Rorschach variables reflecting emotional responsiveness (CF+C, MC-PPD) and emotional management (CF+C/SumC, M-, H, and PHR) among different levels of intellectual ability for both the incarcerated and outpatient samples. The study involved an examination of archival data from incarcerated individuals receiving mental health services and individuals receiving mental health services at a community clinic. Findings indicated there was a significant difference in CF+C/SumC scores between the different levels of care and incarceration status. These results indicate those who are not incarcerated likely have more adaptive emotion management skills to manage internal and external emotionally toned stimuli in comparison to those who are incarcerated, particularly incarcerated individuals who need the highest level of mental health care. Further, the results indicated participants’ responses on the emotional management/human interaction variables (i.e., CF+C/SumC and PHR) were able to significantly classify their incarceration status, with an overall correct classification of 63.3%. Future research is needed to better understand the relationships between incarceration status and EI abilities. Utilizing the Rorschach as a Measurement of the Emotional Intelligence of Incarcerated Populations.

Introduction

In 2013, the United States held over 1,574,000 people in state and federal prisons, reflecting a .3% increase from 2012 and constituting the largest incarcerated population in the world [1]. The Bureau of Justice reported that inmates sentenced for violent offenses comprised 54% of the state prison population in 2012, with an estimated 58% of male and 61% of female inmates in state or federal prison being age 39 years or younger [2]. Thus, young people represent a large percentage of the individuals incarcerated in U.S. jails, raising a concern about the future of these young people, specifically their re-incarceration rates. Results of a study conducted in 2005 by the Department of Justice showed that of all prisoners released in 1994, 67.5% were rearrested within 3 years, 61.7% of whom were convicted of a violent offense [2]. Additionally, the results showed that of all prisoners released in 1983, 62.5% were rearrested within 3 years, 59.6% of whom were convicted of a violent offense [2].

The seemingly increasing numbers of incarcerated individuals and the high degree of recidivism among those attempting to reenter society support a continued need for research to establish assessment measures that not only help clarify overall cognitive and psychological functioning, but also improve overall psychological treatment programs and rehabilitation for incarcerated individuals in the United States [1,2]. Research has shown that individuals with higher cognitive functioning in general are typically better adjusted psychologically, emotionally, and socially [3]. However, given that many prisoners exhibit low levels of cognitive functioning, improving the emotional intelligence (EI) of this population may be one important area of interest related to treatment and rehabilitation [4]. EI reflects the ability to discriminate, monitor, and appropriately label one’s own and other people’s emotions [5]. When people are able to label and monitor their emotions accurately, they are able to utilize emotional information to guide themselves toward more appropriate and healthier thinking and behavior.

Studies have indicated that a large number of individuals who are incarcerated exhibit antisocial and psychopathic traits. For example, Fazel and Danesh found that 47% of incarcerated men in the United States met the criteria for antisocial personality disorder (APD), while 63% of incarcerated men in the United Kingdom met the same criteria [6]. It has long been suggested that individuals with antisocial and psychopathic traits have numerous difficulties with social interaction and often exhibit impairments in various emotional tasks, such as understanding and connecting with others socially and emotionally, suggesting a likely deficit in EI [7-9]. The few studies conducted on the specific correlation between EI and incarcerated individuals showed that those with psychopathy are impaired on a range of EI abilities, suggesting EI is an important area for understanding the deficits of those with psychopathy and for understanding the relationship to recidivism [7].

Emotional intelligence plays an important part in the presence, maintenance, and coping of negative emotions, and therefore may affect the outcomes and specific treatment needs of incarcerated populations. Although there is a growing body of literature to support the crucial role of negative emotional states in the offense and recidivating processes of offenders, there has been relatively little theoretical or applied research in this area [10]. However, the available research strongly supports that negative emotional states are important and dynamic risk factors that increase the risk of reoffending, particularly among those already in forensic settings [10]. Thus, an individual’s ability to identify, process, and manage negative emotional states should be included in all psychological interventions to reduce the likelihood of recidivism.

Three different models have been developed to define EI since the first use of the term in Payne’s doctoral thesis, A Study of Emotion: Developing Emotional Intelligence [11]. Salovey and Mayer developed a model that is widely known and used, called the ability model [5]. The ability model comprises an individual’s ability to process emotional information and use it to navigate his or her social environment [12]. This includes the capacity to accurately perceive emotions, to access and generate emotions to assist thought, to understand emotions and emotional knowledge, and to reflectively regulate emotions so as to promote emotional and intellectual growth [13]. Mayer et al. argued that individuals vary in their ability to process information of an emotional nature and to relate emotional processing to a wider cognition, which often manifests in certain adaptive behaviors [13]. Therefore, if an individual lacks these capacities and abilities, it is suggested that the deficiency will manifest in maladaptive behaviors, such as criminality or psychopathology.

Goleman [14] later proposed a model of EI, subsequently termed the mixed model, because he argued that EI is the combination of Mayer and Salovey’s ability model and a model that would later become known as Petrides’s trait model [15]. Goleman’s mixed model defines EI as an array of skills and characteristics that drive leadership performance. Goleman outlined five main EI constructs: (a) self-awareness, (b) self-regulation, (c) social skill, (d) empathy, and (e) motivation [14]. This “mixed” model supports that individuals are born with a general EI that determines their potential for learning specific emotional competencies later in life [16].

Petrides subsequently proposed a model, called the trait model (trait EI), which focuses on the involvement of behavioral dispositions and self-perceived abilities that are measured through self-report as the basis for EI [15]. As such, trait EI encompasses behavioral dispositions and self-perceived abilities that are measured by self-report, as opposed to the earlier ability model, which refers to specific EI abilities. Furthermore, Petrides and Furnham argued that trait EI should only be investigated within a personality framework, which typically includes variables such as empathy, optimism, and impulsivity, but can also include general constructs such as motivation and happiness [15].

In general, there are several advantages of using the ability model over both the trait model and the mixed model of EI. For instance, the definition used in the ability model is the most “unitary and cohesive” definition (Mayer et al., 2004). Furthermore, the ability model does not include the personality characteristics that are found in the other models, which do not seem to be directly a component of either emotion or intelligence [13].

Along with the different models of EI are different assessment measures. One such measure is the Swinburne University Emotional Intelligence Test (SUEIT), which is designed to measure trait EI [17]. However, it does not assess intelligence, abilities, or skills, as it is limited to the personality framework that is emphasized in trait EI. In fact, few trait EI measures have been developed within a clear theoretical framework, with even fewer having empirical foundations [18]. The Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) is based on a series of emotion-based problem-solving items and is designed to measure ability EI [13]. The MSCEIT was modeled on ability-based IQ tests by testing a person’s ability in each of the four branches of EI outlined by Salovey and Mayer [5].

It then generates scores for each of the branches as well as a total score. The MSCEIT is based on the idea that EI requires attunement to social norms; therefore, it is scored in a consensus fashion, with “higher scores indicating higher overlap between an individual’s answers, and those provided by a worldwide sample of respondents” [19]. It can also be expert scored so the amount of overlap is calculated between an individual’s answers and those provided by a group of emotion researchers. The MSCEIT is unlike standard IQ tests in that its items do not have objectively correct responses. However, according to Spain, Eaton, and Funder, the consensus scoring criterion means it is impossible to create items that a minority can solve because responses are deemed “emotionally intelligent” only if endorsed by the majority of the sample [20]. Thus, ability EI tests cannot be objectively scored because there are no clear-cut criteria for what constitutes a correct response, although research indicates some improvement in these measures [20]. Furthermore, the ability EI measures ignore the inherent subjectivity of emotional experience [20].

The Emotional Competency Inventory (ECI), the Emotional and Social Competency Inventory (ESCI), and the Emotional Social Competency–Universal Edition (ESCI-U) were developed by Goleman and Boyatzis to measure EI based on the mixed model perspective [21]. These measures are designed to provide a behavioral measure of the emotional and social competencies of each individual; however, the developers and users of the ECI and similar methods have failed to provide sufficient information about their psychometric properties [18].

As EI contributes to the presence and maintenance of negative emotions, additional measures that assess EI may offer critical information with regard to the emotional regulation, functioning, and coping abilities of incarcerated individuals who frequently have difficulties appropriately and effectively dealing with negative emotions. For example, the Rorschach (R-PAS) is an evidencesupported, performance-based method that yields insight into the coping styles, emotional regulation, and emotional sensitivity of participants. Furthermore, it adds incremental validity to selfreport findings, as many of the EI measures are solely self-report [22]. The ambiguous and complex stimuli within the Rorschach highlight the individual’s complexity and layering in emotional functioning and processing, both within oneself and with regard to relating to others. Thus, the Rorschach may be a better assessment tool with which to evaluate EI and other emotional regulation variables that may not be as easily accessed through traditionally used self-report measures.

Ordinarily, the assessment of incarcerated individuals involves mostly traditional measures for understanding an inmate’s cognitive, personality, and emotional functioning, typically through measures such as the Wechsler’s Adult Intelligent Scale – Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV), Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI), or Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory – Second Edition (MMPI-2). However, the Rorschach potentially has something additional to add. The Rorschach includes several scales that involve EI abilities, such as emotional lability [23]. For example, research has supported the idea that the Blend% is an indicator of complexity and layering in emotional functioning, which may reflect a personality trait or a reaction to situational stress, including those that involve emotions [24]. It may also indicate confusing emotional experiences or an inability to perceive and understand emotions within oneself, in others, or in the environment.

Other scales that may be associated with emotionally-related processing and responsiveness include the R8910%, CF+C, MCPPD, Cblend, C, and C’ [24]. Additionally, social interactions and quality of relationships are important aspects of EI [25]. Scales that may be associated with human interactions include the M-, H, and PHR scales. Together, these scales may provide a better understanding of an individual’s EI abilities and capabilities than do self-report measures of EI or other traditional assessment measures. This better understanding of these abilities may offer well-needed benefits in the assessment of incarcerated individuals, as these abilities have been found to be related to greater mental health, exemplary job performance, leadership skills, and overall healthier and more adaptive behaviors [26].

Statement of the Problem

The increasing rate of recidivism among those being released from jail and prison continues to highlight flaws within the risk assessments currently being used. EI may be a relevant, but underutilized, concept in the assessment of recidivism risk. The current measures of EI usually are not used in assessing and understanding the cognitive and emotional functioning of incarcerated individuals. Utilizing the Rorschach in conjunction with other measurements may offer a distinctive opportunity to enhance the assessment of an individual’s EI abilities, especially in the assessment of recidivism risk. While EI appears to play an important role in the perception, monitoring, and regulation of negative emotions and human interactions Salovey P & Mayer JD [5], it is not yet known as to how exactly EI abilities are related to criminal behaviors, particularly for those with lower cognitive functioning.

As the number of incarcerated individuals in the United States continues to increase, it appears to be more necessary to understand how problems with emotion regulation and other EI abilities may result in criminal behavior for some people while not for others. The current study was designed to determine the usefulness of a non-traditional assessment (i.e., the Rorschach) as a measure of EI in incarcerated populations. The current study involved the use of a quantitative design and archival data from two different assessment sites. Using the Rorschach system and scores from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), the researcher evaluated the intellectual functioning and EI abilities of adult male prisoners from a California prison for men. The researcher then compared the scores to a sample from an outpatient clinic, which comprised adult males with no known history of incarceration. Each individual in both groups had been administered a psychological battery that included the WAIS-IV and Rorschach Performance Assessment System (R-PAS). These measures were then examined separately to determine each individual’s overall intellectual ability (WAISIV: FSIQ) and two important EI abilities: emotional responsiveness (CF+C, MC-PPD) and emotional management/human interaction (CF+C/SumC, M-, H, and PHR).

Significance of the Study

This study has several important implications for clinical practice. Determining the specific Rorschach variables that are indicative of EI may support the Rorschach’s usefulness in further enhancing the understanding of an inmate’s emotional and social abilities. By doing so, individualized therapeutic interventions can be developed and implemented to improve the inmate’s ability to appropriately respond to and manage emotional situations, regardless of whether said situations are positive or negative. More so, mental health professionals may be able to better identify the social deficits an inmate exhibits and then target these deficits in the therapeutic relationship. Additionally, by comparing these Rorschach variables between lower and higher intellectually functioning individuals (i.e., incarcerated individuals and individuals with no history of incarceration, respectively), clinicians may be able to implement more accurate and beneficial treatment interventions in a way that individuals can cognitively understand. The understanding of EI difficulties can assist mental health professionals in providing better overall treatment that will enable incarcerated patients to have a more solid understanding of social interactions and connections. It was this researcher’s hope that creating better treatment would translate into a decrease in recidivism.

Null hypotheses

HypothesesThe main hypotheses of this study (stated in null form) based on the limited findings available in the literature:

Hypothesis 1: There will be no significant differences in the R-PAS CF+C scores between incarcerated individuals and outpatient clinical subjects.

Hypothesis 2: There will be no significant differences in the R-PAS MC-PPD scores between incarcerated individuals and outpatient clinical subjects.

Hypothesis 3: There will be no significant differences in the R-PAS CF+C/SumC scores between incarcerated individuals and outpatient clinical subjects.

Hypothesis 4: There will be no significant differences in the R-PAS H scores between incarcerated individuals and outpatient clinical subjects.

Hypothesis 5: There will be no significant differences in the M- scores between incarcerated individuals and outpatient clinical subjects.

Hypothesis 6: There will be no significant differences in the PHR scores between incarcerated individuals and outpatient clinical subjects.

Hypothesis 7: There will be no significant differences in the R-PAS variables between individuals with average to above average FSIQ and individuals with below average FSIQ.

Considering that the Rorschach variables of CF+C, MC-PPD, CF+C/SumC, H, M-, and PHR have been demonstrated to be related to EI abilities in previous research, it was expected that incarcerated individuals would show greater impairment on each of these variables compared to individuals in the non-incarcerated sample and the null hypotheses would be rejected.

Methods

Participants

The current study involved the use of archival data gathered from two institutions for a purposeful and convenient sample: a local State prison for men in California, and an outpatient clinic in California. The archival data from the prison consisted of previous assessment batteries that were administered by practicum students to adult male inmates who were referred to students for psychodiagnostics assessment. The archival data from the community clinic consisted of previous assessment batteries also administered by practicum students to adult (i.e., 18 years or older) males who were referred to the clinic for psychodiagnostic or neuropsychological assessment. All of the assessments were completed under the supervision of a licensed psychologist, and 35 batteries from each institution, totaling 70 batteries, was the target sample size. The actual sample size totaled 79 batteries, with 36 batteries from the men’s prison and 43 batteries from the community clinic. The mean subject age of the incarcerated sample (n = 36) was 44.33 (SD = 14.49) years. The mean subject age of the outpatient clinical sample (n = 43) was 28.51 (SD = 9.95) years. The mean subject age for the total sample (N = 79) was 35.72 (SD = 14.50) years. Data from subjects who were previously diagnosed with a known brain injury, a psychotic disorder, or a dementia related disorder were not utilized in this study.

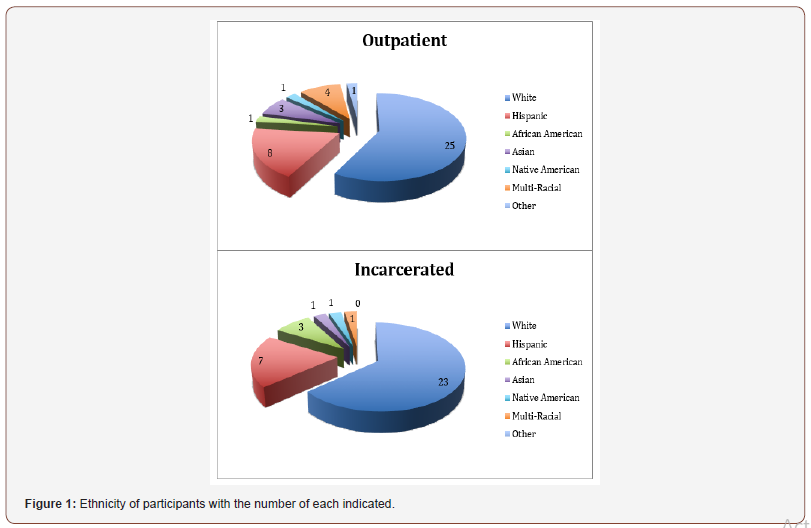

All of the participants were administered the assessment batteries in English (N = 79). The outpatient sample consisted of Caucasian (n = 25), Hispanic (n = 8), African American (n = 1), Asian American (n = 3), Native American (n = 1), and multi-cultural (n= 5) individuals, as shown in (Figure 1). The incarcerated sample consisted of Caucasian (n = 23), Hispanic (n = 7), African American (n = 3), Asian American (n = 1), Native American (n = 1), and multicultural (n = 1) individuals, as shown in (Figure 1).

The participants in this study completed education levels ranging from sixth grade to 22 years of education. The mean years of education completed in the outpatient sample was 14.16 (SD = 11.64), while the mean level of education completed in the incarcerated sample was 11.64 (SD = 2.53).

Measures

The Rorschach Inkblot technique

The Rorschach was used to assess ability EI using the R-PAS scoring system. The Rorschach is an evidence-supported, performance-based method that yields insight into the coping styles, emotional regulation, and emotional sensitivity of participants. The R-PAS scoring system was normalized using a normative reference sample of 640 records from 13 countries. Interrater reliability for both scoring systems has been summarized by meta-analyses, which indicated interrater reliabilities ranging from .82 to .97 [27,28]. Additionally, Exner reported test–retest reliabilities of 41 variables ranging from .26 to .92 over a 1-year interval [20]. The validity of the Rorschach was established by correlating the scales with other known measures and some researchers found an effect size that was “almost identical” to the MMPI [29,30].

Certain Rorschach variables reflecting emotional responsiveness and emotional management/human interaction among different levels of intellectual ability were compared between the incarcerated and outpatient samples. Hypotheses for this study were that there would be a significant difference in EI as reflected by emotional responsiveness (CF+C, MC-PPD) and emotional management/human interaction (CF+C/SumC, M-, H, and PHR) scores on the Rorschach between the incarcerated and non-incarcerated samples.

Wechsler adult intelligence scale-fourth edition

The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Fourth Edition (WAISIV;) was used as a measure of general intellectual functioning [31]. The WAIS-IV is composed of 10 core subtests and five supplemental subtests. The 10 core subtests make up the Full-Scale IQ (FSIQ) and can be used for individuals aged 16 to 90 years. It is a wellestablished scale with high consistency rates and has been highly correlated with the Stanford-Binet IV test (0.88). According to the test manual, the test–retest reliabilities of the WAIS-IV ranged from 0.70 (seven subscales) to 0.90 (two subscales) over a 2- to 12-week time period. The interrater coefficients were also high (>.90).

Procedures

Data from the incarcerated individuals who were referred to the prison’s mental health department were retrieved from patient clinical files, which were located and securely stored in a locked cabinet in the psychology supervisor’s office at the prison. This researcher encoded only information that was pertinent to the current study. At the beginning of the assessment process, each subject was provided with written and verbal informed consent that detailed confidentiality and the limits thereof, the possible use of the data for research purposes, and a detailed explanation of the assessment process. Each inmate was then administered a complete battery that included, at minimum, the Rorschach (using the R-PAS scoring system), the WAIS-IV, and the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-II) or Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI) under the supervision of a licensed psychologist.

The data collected from the outpatient clinic consisted of assessments of adult males who were referred to the clinic for psycho diagnostic or neuropsychological evaluations. At the beginning of the assessment process, each individual was provided with written and verbal informed consent that detailed confidentiality and the limits thereof, and a detailed explanation of the assessment process. These subjects were also administered a battery that included, at minimum, the Rorschach, PAI, and WAISIV by a psycho diagnostic practicum student who was under the supervision of a licensed psychologist. This researcher obtained written approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the sponsoring University and The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS), Research Advisory Committee (RAC) of the State prison system to access the files and extract the requisite information that was necessary for the current study.

The test data and reports used for this study were stored in a confidential locked file cabinet in each of the corresponding program supervisors’ offices. The test data remained confidential and continued to be stored in the same secure, confidential cabinets. The data collected and reviewed for this study were viewed only by this researcher and her dissertation committee. To ensure confidentiality, all identifiable information for the subjects was excluded from the data collection process, including name, inmate or PACTS number, birthdate, and any other identifiable characteristics or information. Furthermore, all of the archival data, including each subject’s assessment data, were placed into an Excel spreadsheet along with necessary demographic information, and each subject was assigned an ID number. The Excel spreadsheet containing this information is password-protected and stored in a password-protected computer, to which only this researcher and her committee members have access. Additionally, the data will be destroyed 2 years after the completion of this study. The assessment data collected for each subject included the FSIQ from the WAIS-IV to assess the subject’s overall cognitive and intellectual functioning. Additionally, the scores from the CF+C, MC-PPD, CF+C/SumC, M-, H, and PHR scales were collected in an attempt to asses two EI abilities: emotional responsiveness and emotional management. The demographic information that was collected and reviewed for each subject included age, race, educational level, and level of care.

Results

Statistical data analysis was conducted using the SPSS software package to determine whether the Rorschach can be used as a measure of EI with incarcerated individuals. Descriptive statistics were calculated on all demographic variables utilized in this study. Comparisons between age, education, and overall level of cognitive functioning of the incarcerated and outpatient nonincarcerated subjects were examined using independent sample t tests. The results of the independent samples t tests are reported below and the means and standard deviations (SD) are presented in (Table 1). Additionally, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to examine the relationships between scores on the emotional responsiveness (CF+C, MC-PPD) and emotional management (CF+C/SumC, M-, H, and PHR) variables, level of care (outpatient, general population outpatient, Correctional Clinical Case Management System [CCCMS], and Mental Health Crisis Bed [MHCB]), incarceration status (incarcerated and non-incarcerated), and level of cognitive functioning (extremely low, borderline, low average, average, high average, superior, and very superior) based on FSIQ scores. Follow-up analyses using age and education as covariates were also conducted. Finally, discriminant function analyses were conducted to determine the extent to which the measures used in this study could differentiate which individuals were in the outpatient group and which were incarcerated.

Independent samples t tests

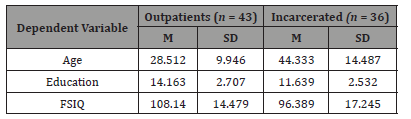

An independent samples 𝑡 test was conducted to compare the difference in age between the outpatient and incarcerated sample subjects. The incarcerated sample subjects were found to be significantly older compared to the outpatient, non-incarcerated sample subjects; 𝑡 (60.253) = -5.549, p = .000. The means and standard deviations are reported in (Table 1).

An independent samples t test was conducted to compare the difference in education level between the outpatient and incarcerated sample subjects. The outpatient, non-incarcerated sample subjects were found to have a significantly higher level of education compared to the incarcerated sample subjects; 𝑡 (77) = 4.250, p = .000. The means and standard deviations are reported in (Table 1).

Table 1: Independent t Test Means and Standard Deviations.

An independent samples 𝑡 test was conducted to compare the difference in overall level of cognitive functioning (i.e., FSIQ) between the outpatient and incarcerated sample subjects. The outpatient, non-incarcerated sample subjects were found to have significantly higher FSIQ scores compared to the incarcerated sample subjects; 𝑡 (77) = 3.293, 𝑝 = .001. The means and standard deviations are reported in (Table 1).

Multivariate analysis of variance

A MANOVA was conducted with the independent variable consisting of four levels of care, one level being outpatient status and the other levels representing the three levels of care of the incarcerated patients: general population (GOP), Correctional Clinical Case Management (CCCMS), and Mental Health Crisis Bed (MHCB). Emotional responsiveness (CF+C, MC-PPD) and emotional management (CF+C/SumC, M-, H, and PHR) scores were used as dependent variables (DVs). The MANOVA did not reveal a statistically significant multivariate effect for level of care in relation to the R-PAS variables, Wilks’ Lambda = .750, F (18, 195.6)= 1.166, p = .293, indicating no overall differences in emotional responsiveness and emotional management among the levels of care.

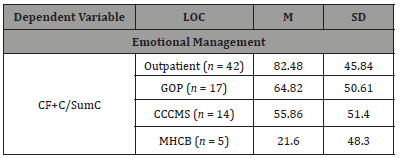

Table 2: Univariate effects for level of care (Means and SDs).

Although the overall MANOVA was not statistically significant, univariate ANOVAs were conducted to examine differences between specific dependent variables among the different levels of care. The individual ANOVAs revealed that one of the measures of emotional management did reflect a difference among the levels of care (CF+C/SumC scores, F [3,74] = 3.106, p = .032), while the remaining variables were not found to be statistically significant across the levels of care. The means and standard deviations for the levels of care on CF+C/SumC are presented in (Table 2).

To determine which care levels differed from one another on the CF+C/SumC measure, post-hoc analyses using Tukey HSD were conducted. The means for each of these comparisons were presented in (Table 2), and the significant overall effect was produced by one specific difference: outpatient versus MHCB (p = .044). Thus, the outpatients scored significantly higher on CF+C/ SumC than the incarcerated prisoners who were housed in the MHCB Unit, or Care Level 3. These results indicate the outpatients likely had more adaptive emotion management skills to manage internal and external emotionally toned stimuli in comparison to those prisoners who may constrict their affect in response to emotional situations.

An additional MANOVA was conducted with emotional responsiveness (CF+C, MC-PPD) and emotional management (CF+C/SumC, M-, H, and PHR) variables as dependent variables (DVs), and incarceration status (i.e., outpatient or incarcerated) as an independent variable (IV). The MANOVA did not reveal a statistically significant multivariate effect for incarceration status in relation to the R-PAS variables, Wilks’ Lambda = .920, F (6, 71) = 1.023, p = .417, indicating no differences in emotional responsiveness and emotional management based on status of incarceration.

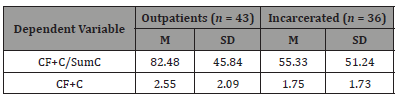

Because the overall MANOVA was not statistically significant and thus did not reveal differences across all of the dependent measures combined, univariate ANOVAs were conducted to examine differences between specific dependent variables among the different statuses of the two groups (i.e., outpatients and incarcerated patients). The results from the univariate F-tests showed CF+C, which reflects an individual’s attachment to his or her own emotions, approached conventional levels of statistical significance, F (1,76) = 3.310, p = .073. However, because it was not statistically significant, Hypothesis 1, which was that there would be no significant differences in the R-PAS CF+C scores between incarcerated individuals and outpatient clinical subjects, failed to be rejected. With regard to CF+C/SumC, which reflects the degree of control over emotional reactions (especially negative emotional reactions), a significant effect was found on this measure for incarceration status, F (1,76) = 6.097, p = .016. Thus, Hypothesis 3, which was that there would be no significant differences in the R-PAS CF+C/SumC scores between incarcerated individuals and outpatient clinical subjects, was rejected, as a difference was observed. The remaining variables were not found to be statistically significantly different between the two groups. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 (no significant differences in the R-PAS MCPPD scores), Hypothesis 4 (no significant differences in the R-PAS H scores), Hypothesis 5 (no significant differences in the M- scores), and Hypothesis 6 (no significant differences in the PHR scores) between incarcerated individuals and outpatient clinical subjects all failed to be rejected. The means and standard deviations for the significant effects are presented in (Table 3).

A final MANOVA was conducted with emotional responsiveness (CF+C, MC-PPD) and emotional management (CF+C/SumC, M-, H, and PHR) as dependent variables (DVs) and level of cognitive functioning (extremely low, borderline, low average, average, high average, superior, and very superior) based on FSIQ score as the independent variable (IV). The MANOVA did not reveal a statistically significant multivariate effect for cognitive functioning in relation to the R-PAS variables, Wilks’ Lambda = .526, F (36, 292.5) = 1.279, p = .140, indicating no overall differences in emotional responsiveness and emotional management scores among the levels of cognitive functioning. Thus, Hypothesis 7, which was that there would be no significant differences in the R-PAS variables between individuals with average to above average FSIQ and individuals with below average FSIQ, failed to be rejected.

Table 3: Independent t Test Means and Standard Deviations.

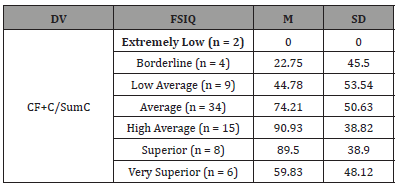

Because the overall MANOVA was not statistically significant and thus did not reveal differences across all of the dependent measures combined, univariate ANOVAs were conducted to examine differences in specific dependent variables among the different levels of cognitive functioning using FSIQ as the basis for classification. The results from the univariate F-tests showed a significant difference among levels of cognitive functioning and CF+C/SumC scores, F (6,71) = 2.660, p = .022, while the remaining variables were not found to be statistically significantly different across the IQ levels. The means and standard deviations for each measure for each level of overall cognitive functioning (i.e., FSIQ) are presented in (Table 4).

Table 4: Univariate effects for FSIQ..

To determine which IQ levels differed from one another on the CF+C/SumC scores that showed an overall significant difference among the levels of overall cognitive functioning, post-hoc analyses using Tukey HSD were conducted. The means for these comparisons were presented in (Table 4); however, no significant overall effects were revealed between FSIQ levels and CF+C/SumC scores.

Discriminant functional analysis

A discriminant functional analysis (DFA) was conducted with the emotional responsiveness (CF+C, MC-PPD) and emotional management (CF+C/SumC, M-, H, and PHR) variables as dependent or predictor variables (DVs), and incarceration status (i.e., outpatient or incarcerated) as the independent or grouping variable Citation: Ashley Ginter, Stephen E Berger, Bina Parekh, Albert Miranda. Emotional Intelligence of Incarcerated Populations as Measured by The Rorschach Inkblot Technique. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 3(2): 2020. OAJAP.MS.ID.000559. DOI: 10.33552/OAJAP.2020.03.000559. Page 8 of 13 (IV). The DFA showed the participants’ responses on emotional responsiveness (CF+C, MC-PPD) and emotional management (CF+C/SumC, M-, H, and PHR) did not significantly classify their incarceration status (outpatient vs. incarcerated), eigenvalue = .086, canonical correlation = .282, Wilks’ Lambda = .920, df = 6, p = .417. The structure coefficients showed the dependent variables of CF+C/SumC (.963) and CF+C (.710) had the strongest correlation with the discriminant function model that was generated. Finally, the DFA correctly classified 32 of 43 outpatient participants and 17 of 36 incarcerated participants with an overall correct classification of 62.8%.

An additional DFA was conducted with the emotional management and human interaction (CF+C/SumC, M-, PHR) variables as dependent or predictor variables (DVs) and the incarceration status of the participants (outpatient vs. incarcerated) as the independent or grouping variable (IV). The DFA showed the participants’ responses on human interaction (CF+C/SumC, M-, PHR) did not significantly classify their incarceration status (outpatient vs. incarcerated), although it did approach conventional levels of clinical significance, eigenvalue = .090, canonical correlation = .287, Wilks’ Lambda = .918, df = 3, p = .090. The structure coefficients showed that the dependent variable of CF+C/SumC (.948) had the strongest correlation with the discriminant function model that was generated. Finally, the DFA correctly classified 32 of 43 outpatient participants and 16 of 36 incarcerated participants with an overall correct classification of 60.8%.

A final DFA was conducted with the emotional management/ human interaction variables (CF+C/SumC and PHR) as dependent or predictor variables (DVs) and the incarceration status of the participants (outpatient vs. incarcerated) as the independent or grouping variable (IV). The DFA showed the participants’ responses on emotional management/human interaction (CF+C/SumC and PHR) were able to significantly classify their incarceration status (outpatient vs. incarcerated), eigenvalue = .085, canonical correlation = .280, Wilks’ Lambda = .922, df = 2, p = .045. The structure coefficients showed the dependent variable of CF+C/ SumC had the strongest correlation with the discriminant function model that was generated. Finally, the DFA correctly classified 34 of 43 outpatient participants and 16 of 36 incarcerated participants with an overall classification of 63.3%.

Discussion

The present study was designed to address several specific goals. The first was to analyze the differences between incarcerated and non-incarcerated individuals with regard to their scores on specific Rorschach variables associated with EI. Second, this study was designed to investigate the differences in certain Rorschach variables reflecting emotional responsiveness and emotional management/human interaction among different levels of intellectual ability between incarcerated and outpatient samples. The hypotheses for this study were that there would be a significant difference in EI, as reflected by emotional responsiveness (CF+C, MC-PPD) and emotional management/human interaction (CF+C/ SumC, M-, H, and PHR) scores on the Rorschach, between the incarcerated and non-incarcerated samples. Specifically, it was expected that incarcerated individuals would demonstrate lower levels of EI compared to the non-incarcerated outpatient sample. An additional hypothesis for this study was that there would be significant differences in EI abilities between the different levels of cognitive functioning, with those individuals who demonstrated lower levels of cognitive functioning exhibiting a lower level of EI.

Based on the findings from this study, several of the hypotheses were not supported. Overall, it appeared the individuals who were incarcerated and receiving mental health services had similar abilities related to emotional responsiveness and emotional management/human interaction as those who were in the community and receiving mental health services. For instance, both the incarcerated sample and the non-incarcerated outpatient sample scored at the 57th percentile on the Rorschach variable MC-PPD. This variable is suggested to be a measurement of coping effectiveness. Thus, incarcerated individuals would be expected to demonstrate a deficit in effective resources to cope with everyday life and be more negatively affected by stress compared to those with higher levels of resources, such as the outpatient sample or the normative sample. Prisoners should therefore have a lower MC-PPD score than the outpatient sample and the normative group; however, this was not indicated in the current study. Further, incarcerated individuals scored at the 60th percentile while the non-incarcerated sample scored at the 57th percentile on M-, which measures the ability to accurately understand the emotions of others and others in general. It was expected that incarcerated individuals would produce poorer scores on this variable (i.e., prisoners would score at a higher percentile) than the outpatients, which would suggest prisoners have more of a distorted understanding of people compared to the outpatient and normative populations. Although this difference was not statistically significant, the prisoners produced scores in the direction of poorer emotional understanding of others, which was in the expected direction.

With regard to the variable H, which measures healthy human reactions, the incarcerated sample scored at the 47th percentile while the non-incarcerated sample scored at the 44th percentile. It was expected that the incarcerated sample would produce lower scores than the outpatient and normative samples, which would suggest they have difficulties understanding others as complex whole beings. This was not indicated by the current study’s results, as the three-percentile ranking difference was likely not meaningful. However, the non-incarcerated sample falling at the 44th percentile compared to the normative 50th percentile may be of some significance, and thus, should be considered as a focus for future research.

Further, the PHR scores of the incarcerated sample fell at the 60th percentile while the scores of the non-incarcerated sample fell at the 65th percentile. PHR is used as a measure of interpersonal competency and the capacity for relatedness. Individuals with high PHR scores typically have a problematic or less adaptive understanding of oneself and others. Additionally, it has been suggested through research that incarcerated individuals often develop an “emotional flatness” that negatively affects their human interaction abilities, such as their understanding of others [32]. Thus, incarcerated individuals would be expected to produce a higher score on PHR than the outpatients and normative sample. However, this was once again not supported by the findings of the current study. Taken together, these findings might suggest that prisoners (seeking mental health services) actually have a better understanding of other people than do non-incarcerated people seeking mental health services. Perhaps one thing that gets the incarcerated group in trouble while in prison, and perhaps increases their risk of recidivism, is that they learn to misuse what they understand about others. In other words, incarcerated individuals may be more prone to violate human relationships upon being incarcerated. Although this is a possibility, it extends beyond the purpose of this particular study and should be considered for future research. More specifically, future research should be conducted to determine whether incarcerated individuals violated human relationships prior to being incarcerated (i.e., examine each person’s offense conduct) as well as during their incarceration (i.e., consider incident reports or assaultive behavior).

There was, however, a notable difference on the CF+C/SumC variable between the two groups. The incarcerated sample scored at the .13th percentile while the non-incarcerated outpatient sample scored at the 11th percentile. CF+C/SumC is suggested to measure an individual’s reactions to emotional provocation. Those with extremely low CF+C/SumC scores typically constrict their affect in response to emotional situations, which negatively affects their ability to enjoy life and to enjoy others. It was expected that those who were incarcerated would produce extremely low scores on this variable when compared to the outpatients and to the normative sample. Results showed that prisoners did, in fact, produce an extremely low score when compared to both the outpatients and the normative sample; however, the outpatient sample also produced an extremely low score when compared to the normative sample. This finding is interesting because, although there was not a statistically significant difference between the two sample groups, outpatients receiving mental health services as well as incarcerated individuals receiving mental health services may exhibit similar EI deficits, particularly emotional management abilities, that are far beyond what would be typically found in the general population. Once again, it is possible that the results reflect that incarcerated individuals misuse their understanding of others, which combines with emotional constriction and contributes to them getting into legal trouble, whereas the outpatients simply have impaired interpersonal relationships.

The overall finding of no significant difference in EI between the incarcerated and non-incarcerated individuals (all of whom were receiving mental health services) was extremely surprising, as the available literature indicates differences should exist for incarcerated individuals given what is known about the typical characteristics and lifestyles of those who are incarcerated [33- 42]. One factor that may have affected the results of this study was the samples from which the findings were gathered. The control/ comparison group comprised individuals who, although still living in the community, were seeking mental health services at a local mental health clinic. It may be that the outpatient sample did not constitute a true control group that was representative of the general population. These results also suggest that the more important variable related to EI may not be incarceration status, but rather mental health needs.

Consistent with the notion that mental health needs are most important in EI functioning rather than something about incarceration status that is most relevant, is an interesting and possibly important and revealing finding involving EI and the different levels of care needed by the participants. The relationship found in this study regarding emotional management and those requiring the highest level of care may support the original hypotheses and previous research indicating that deficits in EI exist among those with mental illnesses [43]. The researcher examined the differences in EI abilities between the various levels of care in the two sample groups. This included outpatient care for the non-incarcerated sample, and the general population (GOP), Correctional Clinical Case Management (CCCMS), and the Mental Health Crisis Bed (MHCB) levels of care for the incarcerated sample. An individual considered for the GOP generally exhibits minimal or no mental health symptoms, while those considered for the CCCMS level often endorse a range of mental health symptoms and require ongoing mental health treatment or services. Those considered for the MHCB, however, often exemplify severe and acute mental health symptoms and would typically be housed in an inpatient facility if they were out in the community.

Results showed that both the incarcerated and nonincarcerated samples scored much lower on CF+C/SumC when compared to the normative sample provided in the R-PAS manual; however, the incarcerated sample, particularly those in the MHCB, scored lower than the non-incarcerated outpatients on CF+C/ SumC. More specifically, those in the MHCB scored at the .13th percentile and those within the CCCMS level of care scored at the .17th percentile on CF+C/SumC. Those in the GOP scored at the .99th percentile, while the non-incarcerated outpatient sample scored at the 12th percentile on the same variable. This indicates that in contrast to the incarcerated individuals needing the greatest level of institutional care, the outpatients likely had more adaptive emotion management skills to manage both internal and external emotionally toned stimuli. In contrast, individuals in the MHCB likely severely lack adaptive emotion management skills and may constrict their affect in responding to emotional situations.

These results lead to several important findings and implications. The first is that individuals with more severe and acute mental health symptomology will likely exhibit the most significant deficits in EI abilities, specifically emotional management abilities. Second, individuals with any mental health symptomology will likely demonstrate impaired EI abilities when compared to a normative sample. Third, the Rorschach may be an “objective” indicator as to the level of care an inmate needs, as those prisoners receiving the highest level of care were seemingly “housed” or classified accurately

Interestingly, no difference was found in emotional responsiveness or on the human interaction scales of EI between the different levels of care. However, a notable difference on the H and PHR variables was revealed when compared to the normative sample. For example, those in the MHCB scored at the 18th percentile on H and at the 37th percentile on PHR. Although these scores did not fall below one standard deviation of the mean, they were the lowest scores of all the levels of care when compared to the normative sample. What is interesting about this particular finding is that the lower PHR scores suggest those with more severe and acute mental health symptomology are able to understand others as complex humans similarly as those with less severe mental illnesses and suggests interpersonal competency. This may be an example of the aforementioned notion regarding prisoners misusing their ability to relate to others. These contradictory findings are interesting and should be explored further in future research to determine the specific role of human relations in EI, as well as in mental illnesses.

The lack of difference in the emotional responsiveness and human interaction scales between the different levels of care was interesting because it leads to the idea that, in general, prisoners are equally capable of producing emotional responses to internal and external emotional stimuli as are their non-incarcerated counterparts. Additionally, prisoners may exhibit similar abilities as non-incarcerated individuals in recognizing emotionality in others and may be equally successful at developing and maintaining interpersonal relationships; however, the aforementioned findings support that prisoners who also have a severe mental illness lack the ability to manage the emotional responses they experience. These findings support that incarcerated individuals with acute or severe mental illnesses likely have more difficulties managing and coping with their own emotions than prisoners in lower levels of care and people in the community-even those in need of mental health services. These findings indicate that the treatment of incarcerated individuals should focus more on emotion management skills, especially with those who have more severe mental illnesses.

Additionally, the researcher expected to see differences in scores on the Rorschach variables between those with below average cognitive functioning and those with above average cognitive functioning. More specifically, research has shown that incarcerated individuals typically exhibit lower than average IQ [44]. Thus, incarcerated individuals should have produced lower MC-PPD, H, and CF+C/SumC scores and higher PHR and M- scores. However, the different levels of cognitive functioning did not appear to affect the scores on the MC-PPD and M- variables when compared to the normative scores provided in the R-PAS manual, despite the outpatient sample having a significantly higher FSIQ than the incarcerated sample. However, those who fell within the borderline level of intellectual functioning produced the only notable score on the H variable, as they scored at the 7th percentile when compared to the normative sample. No additional significant differences were noted between the different levels of intellectual functioning on this variable. In addition, the only notable score on the PHR variable was for those who exhibited extremely low levels of IQ, as they scored at the 11th percentile when compared to the normative sample.

The lower H score produced by those with a borderline level of IQ suggests that these individuals may have more difficulties developing and maintaining healthy relationships compared to others with higher levels of intellectual functioning. However, the lower PHR scores produced by those with extremely low IQ suggests a capacity for interpersonal competency and relatedness. When taken together, these findings show that perhaps individuals with lower than average levels of intellectual functioning have a similar capacity for interpersonal relatedness and understanding as those with average or above average IQs; however, perhaps they misuse their understanding of relationships in maladaptive ways, which causes them to have unhealthy relationships. Future research should be conducted into this notion by obtaining a larger sample size and looking more closely at the relationship (or lack thereof) of lower intellectual functioning and human interaction abilities, as measured by PHR and H on the Rorschach.

Last, and most importantly, the CF+C/SumC variable produced interesting differences once again, although it should be noted that the sample in some instances was quite small. There was a tendency of higher IQ scores to be associated with higher ranking (normative percentile rank) on this variable. Individuals with borderline (n = 4) and low average (n = 9) intellectual functioning only scored at the .13th percentile, while those with an average IQ (n = 34) scored at the 4th percentile. Further, individuals with high average IQ (n = 15) scored at the 27th percentile and those with superior IQ (n = 8) fell at the 25th percentile. Last, those with very superior IQ (n = 6) fell at the .38th percentile.

This finding that individuals with below average IQ produced significantly lower scores on CF+C/SumC raises the possibility that perhaps prisoners are generally impaired in EI, specifically emotional management abilities, and that their EI is independent of IQ level. Prior research has revealed something similar, in that individuals with antisocial or psychopathic traits exhibited deficits in EI abilities despite having average or above average IQ scores [7,37,45,46]. Yet another factor to consider is that the majority of the prisoners examined in this study were those who needed mental health services. Perhaps the findings are specific to the relationship (or lack thereof) of IQ and EI for prisoners in need of mental health services. Thus, researchers need to look specifically at the diagnoses of incarcerated individuals and the differences in EI abilities among those with different mental health diagnoses in the future.

Clinical implications

The fact that those prisoners receiving the highest level of care were seemingly “housed” or classified accurately suggests the Rorschach may be an “objective” indicator of the level of care an inmate needs. Thus, the Rorschach may be a beneficial assessment to add to the typical diagnostic battery utilized with prisoners. Additionally, despite the limitations of the current study, uncovering the potential relationship between specific Rorschach variables and EI would ultimately lead to improved treatment outcomes for incarcerated individuals by enhancing clinicians’ understanding of the patient’s emotional and social abilities. For example, results of this study support that prisoners who also have a severe mental illness lack the ability to manage the emotional arousal they experience. In other words, incarcerated individuals with acute or severe mental illnesses likely have more difficulties managing and coping with emotions compared to individuals in lower levels of care within the prison and those out in the community. These findings support that the treatment of incarcerated individuals, especially those who have more severe mental illnesses, should focus more on the development of emotional management skills. For example, mental health professionals could implement an emotion regulation or problem-solving curricula to provide opportunities for individuals to learn new and healthy coping and problemsolving skills. This could include behavior modification techniques, such as shaping and reinforcement, as well as skills such as rational self-analyses, relaxation techniques, self-soothing techniques, and other tools to help each individual control impulsive feelings and behaviors. By understanding the emotional management abilities of prisoners, especially those abilities measured by the Rorschach variable CF+C/SumC, clinicians can implement techniques that will allow criminal patients to have a more solid understanding of their emotions, which could potentially translate into more adaptive emotion management, social interactions, and connections, as perhaps even a decrease in recidivism.

In addition to helping prisoners increase their emotional management skills, it may also be important for clinicians to help address any social or human interaction deficits the prisoners may exhibit. By doing so, a stronger and more effective therapeutic alliance can be established, which has been shown to be one of the most influential factors contributing to successful treatment. Furthermore, by increasing the prisoner’s interpersonal competencies, he or she will likely be more able to utilize these skills both within the prison and out in the community. This may help to improve the prisoner’s social support system and help-seeking behaviors, both of which can decrease the likelihood of reoffending. The implications for helping incarcerated individuals not to commit new crimes upon being released are vast. For instance, it would contribute to an increase in public safety as well as a decrease in overcrowding in prisons. This inevitably would lead to smaller caseloads for parole or probation officers, which, in turn, would increase their ability to effectively supervise their parolees and probationers. These are just a few of the many global implications of reduced recidivism.

Limitations and future direction

There are several limitations to consider regarding the current study. For instance, one limitation that may have contributed to the findings of this study was the limited sample size. The limited sample size (N = 79) may have not only affected the generalizability of the results to other populations, it may have affected the sensitivity to small but real differences in this study. For example, there were several findings that approached conventional levels of statistical significance. Perhaps a larger study would be more sensitive to these differences and shed light on the distinctions between the EI abilities among the two populations. Because the current study only included archival data consisting of the R-PAS (rather than the R-PAS and the Exner system), the number of clinical profiles available was limited. Future research studies may benefit from obtaining a larger sample size for both the control and focus groups, and a determination of whether the R-PAS or the Exner system is more sensitive to the prisoner population.

Additionally, the specific Rorschach variables used to assess EI may have affected the results of the current study. The researcher utilized only a portion of the Rorschach variables thought to be associated with various aspects of EI based on current research and theory [24]. Perhaps examining other variables, such as WsumC, Blend%, and R8910%, may contribute to additional significant findings. For example, the WsumC score is thought to be related to emotional responsiveness within the environment. This may be indicative of a willingness to process and respond to emotion, which has been associated with adaptation and psychological strength within the individual. Blend% is an indicator of complexity and layering in emotional functioning and may also indicate confusing emotional experiences, or an inability to perceive and understand emotions within oneself, in others, or in the environment. Additionally, R8910% may be associated with emotionally related processing and responsiveness [24]. These particular variables have not been supported in the literature as being related to components of EI as strongly as the variables that were used in the current study, but it would be valuable to conduct future research to determine whether these variables are more sensitive to the aspects of EI that have been proposed as important in the literature [24]. Furthermore, it would be valuable to expand the understanding of CF+C/SumC as a measure of emotional management, given that this variable was consistently affected in incarcerated individuals in the current study. Similarly, the selected groupings of the Rorschach variables may have also been a limitation of the current study. It is possible that by combining the human interaction and emotional management variables, the grouping became less sensitive to the specific differences between distinctive emotional intelligence abilities. By examining the human interaction and emotional management variables separately, future researchers may discover more specific limitations of incarcerated individuals with regard to EI abilities.

Other limitations of the current study are noteworthy. For example, one limitation stemmed from obtaining data from only two locations, as the samples used may not be an accurate representation of the populations to which this researcher wanted to generalize the findings. Another important limitation of the study was related to the administration, scoring, and interpretation processes conducted by the practicum students. For example, although the students were under the direct supervision of licensed clinical psychologists, variances among the supervising psychologists and in the overall training of the students, may have caused differences in the administration of the Rorschach that could have potentially affected the accuracy of the results, as could differences in the scoring tendencies of the supervisors.

Furthermore, the differences between the two testing sites in which the students were employed may also be an important limitation, as the participants from both settings may have had vastly different experiences with regard to the testing environment. For instance, those individuals from the prison setting may have had a less than standard/usual testing environment, as prisons are often less quiet, and more time constraints exist. In contrast, those assessed at the outpatient clinic used in this study and other outpatient clinics typically have access to less distracting environments and are able to utilize their time more effectively. Additionally, those in a prison setting are often mandated to obtain treatment or are referred by external forces, and typically present with high levels of defensiveness, caution, or alternative motives (e.g., secondary gain, medication, etc.). Those in outpatient settings, however, are typically self-referred, and thus are not as defensive or resentful toward treatment; therefore, their test results are more likely to be valid. This researcher attempted to neutralize this limitation by examining the validity of each participant’s PAI or MMPI as these measures include validity scales that are overall good indicators of the participant’s general approach to the assessment process. Those batteries that did not contain a valid PAI or MMPI were not included in this study. However, it is still essential that these confounding factors be taken into account when interpreting the results of the current study.

Another consideration for future research is to examine more specifically the quality of coping skills being measured by MC-PPD. This particular Rorschach variable assesses an individual’s ability to cope (MC), as well as the amount of perceived stress the individual is experiencing (PPD). Additionally, it aims to measure whether or not an individual’s coping skills are adequately working, although it does not reveal the quality of said coping skills. More specifically, an individual may be utilizing maladaptive or unhealthy coping skills, such as denial, substances, and isolation, to name a few. This particular Rorschach variable does not assess this possibility, however. Thus, an individual may score higher on MC-PPD despite utilizing what would typically be considered unhealthy coping skills. Additionally, if an individual withdraws or engages in denial, the clinician cannot truly evaluate what the individual is truly experiencing.

Last, future researchers may consider examining the relationship between EI abilities via the Rorschach variables and an individual’s Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI) score, rather than the FSIQ from the WAIS-IV. According to the WAIS-IV manual, the PRI is designed to measure fluid reasoning in the perceptual domain [31]. This involves tasks that assess nonverbal concept formation, visual perception and organization, visual-motor coordination, learning, and visual stimuli abilities. Because the Rorschach is a nonverbal, perceptual, and visual task, an individual’s PRI score may offer more information about his or her response patterns to the EI ability variables on the Rorschach Inkblot Test.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations of the current study, it is still important to have a better understanding of EI abilities among incarcerated populations. Perhaps equally important is that researchers and clinicians find a more accurate measure of EI that can provide support for, or perhaps take the place of, the current self-report measures of EI. Ermer E, et al. argued that it is important to understand EI among incarcerated individuals, and it is even more important to understand the relationship of EI deficits and recidivism rates [7]. If the Rorschach variables that are suspected of measuring components of EI are not detecting these abilities in incarcerated populations, then the question remains regarding how to better evaluate these abilities. Although there has been limited research, the research that is available on the relationship between EI and crime shows it is an area that can provide insight into reducing the likelihood of prisoners reoffending. Thus, further research is necessary to gain a greater understanding of the role of EI in criminal behavior and the implications of EI deficits on crime in general. The findings of this study clearly indicate the Rorschach is at least an objective indicator of the level of care an incarcerated individual needs and is able to provide some information regarding these individuals’ EI abilities.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of Interest.

References

- Carson EA (2014) Prisoners in 2013.

- Bureau of Justice (2015) Reentry trends in the USA.

- Milgram RM, Milgram NA (1976) Personality characteristics of gifted Israeli children. J Genet Psychol 129(2): 185-194.

- Lindsay WR, Hastings RP, Griffiths DM, Hayes SC (2007) Trends and challenges in forensic research on offenders with intellectual disability. J Intellect Dev Disabil 32(2): 55-61.

- Salovey P, Mayer JD (1990) Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality 9(3): 185-212.

- Fazel S, Danesh J (2002) Serious mental disorder in 23,000 prisoners: A systematic review of 62 surveys. Lancet 359 (9306): 545-550.

- Ermer E, Kahn RE, Salovey P, Kiehl KA (2012) Emotional intelligence in incarcerated men with psychopathic traits. J Pers Soc Psychol 103(1): 194-204.

- Grieve R, Mahar D (2010) The emotional manipulation-psychopathy nexus: Relationships with emotional intelligence, alexithymia and ethical position. Personality and Individual Differences 48(8): 945-950.

- Lishner DA, Swim ER, Hong PY, Vitacco MJ (2011) Psychopathy and ability emotional intelligence: Widespread or limited association among facets. Personality and Individual Differences 50(7): 1029-1033.

- Day A (2009) Offender emotion and self-regulation: Implications for offender rehabilitation programming. Psychology Crime & Law 15(2&3): 119-130.

- Payne WL (1985) A study of emotion: Developing emotional intelligence. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section A. Humanities and Social Sciences 47(1): 203.

- Salovey P, Sluyter D (1997) What is emotional intelligence? In: Salovey P, Sluyter DJ (eds), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Implications for educators, Basic Books, USA, p. 3-31.

- Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR (2004) Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings, and implications. Psychological Inquiry 15(3): 197-215.

- Goleman D (1995) Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. Bantam Dell, USA.

- Petrides KV, Furnham A (2000) On the dimensional structure of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences 29(2): 313-320.

- Boyatzis RE, Goleman D, Rhee K (2000) Clustering competence in emotional intelligence: Insights from the Emotional Competence Inventory (ECI)s. In: Bar On R, Parker JDA (eds), Handbook of emotional intelligence, Jossey Bass, USA, pp. 343-362.

- Palmer B‚ Stough C (2001) SUEIT: Swinburne University Emotional Intelligence Test: Interim technical manual V2. Melbourne, Organisational Psychology Research Unit‚ Swinburne University, Australia.

- Perez JC, Petrides KV, Furnham A (2005) Measuring trait emotional intelligence. In: Schulze R, Roberts RD (eds), Emotional intelligence: An international handbook, Hogrefe & Huber Publishers, UK, pp. 123-143.

- Singh Rajput R (2016) Impact of personality, emotional intelligence, intrinsic motivation, and wellbeing. Lulu Publication, USA.

- Spain JS, Eaton LG, Funder DC (2000) Perspectives on personality: The relative accuracy of self-versus others for the prediction of emotion and behavior. J Pers 68(5): 837-867.

- Bar On R, Parker JD (2000) The handbook of emotional intelligence: Theory, development, assessment, and application at home, school and in the workplace. Jossey Bass, USA.

- Erard RE, Viglione DJ (2014) The Rorschach Performance Assessment System (R-PAS) in child custody evaluations. Journal of Child Custody 11(3): 159-180.

- Mayer JD, Di Paolo M, Salovey P (1990) Perceiving affective content in ambiguous visual stimuli: A component of emotional intelligence. J Pers Assess 54(3-4): 772-781.

- Meyer GJ, Viglione DJ, Mihura JL, Erard RE, Erdberg P (2011) Rorschach Performance Assessment System: Administration, coding, interpretation, and technical manual. USA.

- Lopes PN, Salovey P, Straus R (2003) Emotional intelligence, personality, and the perceived quality of social relationships. Personality and Individual Differences 35(3): 641-658.

- Mehrabian A (2000) Beyond IQ: Broad-based measurement of individual success potential or “emotional intelligence”. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr 126(2): 133-239.

- Meyer GJ, Hilsenroth MJ, Baxter D, Exner JE, Fowler JC, et al. (2002) An examination of interrater reliability for scoring the Rorschach Comprehensive System in eight data sets. J Pers Assess 78(2): 219-274.

- Viglione DJ, Taylor N (2003) Empirical support for interrater reliability of Rorschach Comprehensive System coding. J Clin Psychol 59(1): 111-121.

- Growth Marnat G, Wright AJ (2016) Handbook of psychological assessment 6th (edn), In: Hoboken NJ (Ed.), John Wiley & Sons publishers, USA.

- Weiner IB (2001) Advancing the science of psychological assessment: The Rorschach inkblot method as exemplar. Psychol Assess13(4): 423-432.

- Wechsler D (2008) Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 4th (edn), Psychological Corporation, USA.

- Haney C (2001) The psychological impact of incarceration: Implications for post-prison adjustment.

- Ammons RB, Ammons CH (1962) The Quick Test (QT): Professional manual. Psychological Reports 11(1): 111-161.

- Blair R (2005) Responding to the emotions of others: Dissociating forms of empathy through the study of typical and psychiatric populations. Consciousness and Cognition 14: 698-718.

- Blair KS, Morton J, Leonard A, Blair RJ (2006) Impaired decision-making on the basis of both reward and punishment information in individuals with psychopathy. Personality and Individual Differences 41(1): 155-165.

- Salovey P, Mayer JD, Goldman SL, Turvey C, Palfai TP (1995) Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In: Pennebaker JW (ed), Emotion, disclosure, and health, American Psychological Association, USA, pp. 125-154.

- Cleckley ES (1988) The mask of sanity 5th (edn), C.V. Mosby Co, USA.

- Franks KW, Sreenivasan S, Spray BJ, Kirkish P (2009) The mangled butterfly: Rorschach results from 45 violent psychopaths. Behav Sci Law 27(4): 491-506.

- Hare RD (1991) The Hare Psychopathy Checklist revised (edn), Multi-Health Systems, USA.

- Morrison D, Gilbert P (2001) Social rank, shame and anger in primary and secondary psychopaths. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry 12(2): 330-356.

- Savitsky JC, Czyzewski D, Dubord D, Kaminsky S (1976) Age and emotion of an offender as determinants of adult punitive reactions. J Pers 44(2): 311-320.

- Van Rooy DL, Alonso A, Viswesvaran C (2004) Emotional intelligence: A meta-analytic investigation of predictive validity and nomological net. Journal of Vocational Behavior 65(1): 71-95.

- Reik T (1952) Listening with the third ear: The inner experience of a psychoanalyst. Farrer, Straus& CO, USA.

- Ellis L, Walsh A (2003) Crime, delinquency and intelligence: A review of the worldwide literature. In: Nyborg H (edr), The scientific study of general intelligence: Tribute to Arthur R Jensen, Pergamon Press, USA, pp. 343-366.

- Copestake S, Gray NS, Snowden RJ (2013) Emotional intelligence and psychopathy: A comparison of trait and ability measures. Emotion 13(4): 691-702.

- Malterer MB, Glass SJ, Newman JP (2008) Psychopathy and trait emotional intelligence. Pers Individ Dif 44(3): 735-745.

-

Ashley Ginter, Stephen E Berger, Bina Parekh, Albert Miranda. Emotional Intelligence of Incarcerated Populations as Measured by The Rorschach Inkblot Technique. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 3(2): 2020. OAJAP.MS.ID.000559.

Emotional intelligence, Rorschach variables, Emotional management, Emotional responsiveness, Mental health, Outpatient, Incarceration status, Samples

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.