Research Article

Research Article

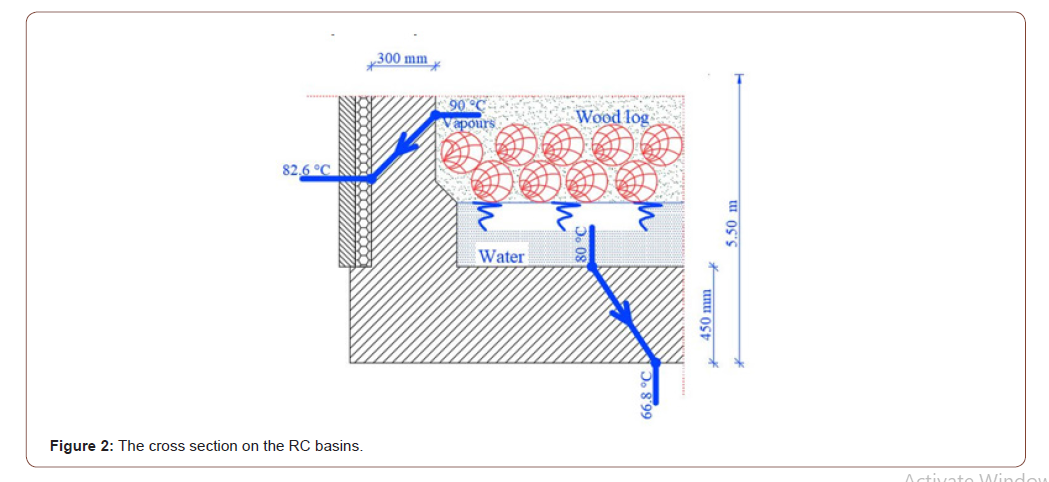

Disordered Eating and Body Image Among NCAA Division I and II Female Soccer Players

Samantha Lussie1*, Stephen E. Berge2 and Bina Parek3

Restoration Center Chicago, Il, United States

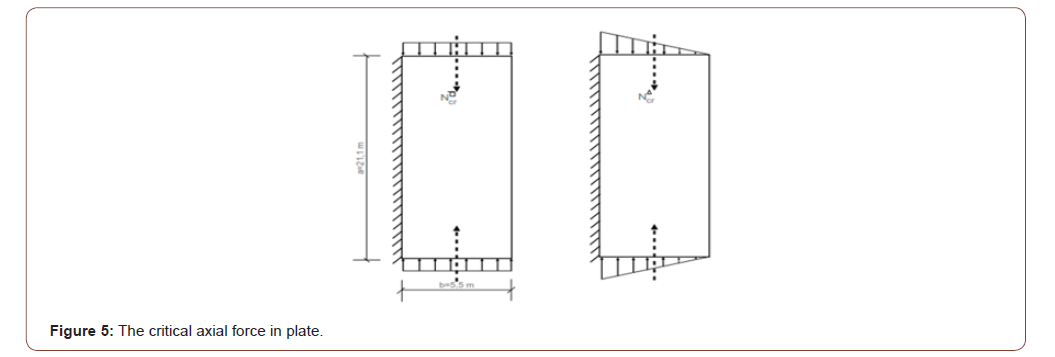

The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Irvine, CA. United States

Samantha Lussier, Restoration Center, Chicago, IL, United States.

Received Date: August 24, 2020; Published Date: December 11, 2020

Abstract

The main objective of this study was to develop an increased awareness regarding disordered eating symptoms among female athletes who participate in the “non-lean sport” of American soccer. This study focused on disordered eating, social physique anxiety as it is related to disordered eating among female athletes, and social pressures as well as women’s body image issues. Women collegiate NCAA Division I and II soccer players, both current and alumni, were invited to complete a demographic questionnaire, the Questionnaire for Eating Disorders Diagnosis (Q-EDD), and the ATHLETE Questionnaire. Results indicated that over 30% of the respondents were classified as eating disordered or symptomatic. Two of the participants earned scores that classified them as having eating disorders according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria. Another 16 women were found to be classified as symptomatic, and 39 of the participants were categorized as asymptomatic. Significant differences between symptomatic and asymptomatic respondents were obtained for three ATHLETE subscales: (a) Your Body and Sports, Drive for Thinness and Performance; (b) Feelings about Your Body, Social Pressure on Body Shape; and (c) Feelings about Eating, Social Pressure on Eating. While Division I and Division II players were compared, and current and alumni players were compared, as well, the significant finding was for Division I v. Division II on the Feelings about Being an Athlete, Athlete Identity subscale. Division II current players exhibited a significantly higher endorsement of the importance of being an athlete to their identity than did Division I current female players. The Q-EDD results were comparable to larger studies that examined only Division I female athletes. Trends were identified among Division I and II players that warrant further research. Some specific risk factors for female collegiate soccer players are discussed. Finally, alumni respondents also exhibited a significant incidence of symptoms of an eating disordered.

Keywords: Body Image; Eating Disorders; Female Soccer Players

Introduction

According to Eating Disorders, the Journal of Treatment and Prevention, an estimated 19%-30% of college females are diagnosed with an eating disorder [1]. Stanford-Martens et al. asserted that there is a higher risk for prevalence of disordered eating among female athletes when compared to the general population [2]. Furthermore, they reported that female athletes are at a high risk for eating disorders as a result of the fact that approximately 14%-19% of them report disordered eating symptoms, although the symptom levels are not severe enough for them to be considered clinically impaired.

Female athletes are at risk of developing eating disorders and engaging in unhealthy eating behaviors in order to obtain a desired weight. In addition to facing the societal pressures from the United States media to be thin, this particular group of women also endures pressure regarding their bodies’ appearance and performance within the context of their specific sport’s culture [3]. These pressures can come from coaches, social comparisons with teammates, team weigh-ins, performance demands, physique-revealing uniforms, and judging criteria [4].

So how common are eating disorders among female athletes? Johnson C, et al. [5], addressed this question by asking 1,445 male and female student athletes from 11 Division I schools to fill out a 133-item questionnaire [6]. The researchers did not find any females who met the full DSM-IV-TR criteria for anorexia, and only 1.1% met the full criteria for bulimia. However, many of the female athletes reported symptoms and attitudes that placed them at risk for anorexia nervosa (2.85%) or bulimia nervosa (9.2%). Furthermore, some who were not considered to have clinically significant symptomatology did endorse distorted eating behaviors, such as the 10.85% of the female athletes who admitted binge eating a minimum of once per week and 5.52% of the females who reported purging behavior (e.g., vomiting, laxatives, diuretics) on a weekly or greater basis.

There is disagreement whether different sports have a differential impact on disordered eating symptoms of female athletes. Hausenblas & Carron [7], suggested that females who participate in “lean sports” such as figure skating, gymnastics, distance running, and diving are at a greater risk for exhibiting disordered eating symptoms than athletes competing in “nonlean” sports such as soccer, basketball, volleyball, and softball [7]. The increased risk is believed to be a result of the application of weight classifications, weight itself, or small body size being important to performance success as well as to subjective evaluation and aesthetic ideals that coexist in the minds of the athletes [7]. However, there is evidence to the contrary that suggests that there is no relationship between sport type and disordered eating classification [4]. In contrast to those findings, results of several investigations indicated that there is a higher prevalence of disordered eating among athletes when compared to nonathlete, same-age peers [2,4,8]. Thus, while female athletes may not be exhibiting full blown eating disorders, there remain indications that they are suffering from disordered eating type symptoms, whether they participate in so-called lean or nonlean sports [2].

Research indicates that even female athletes without the demand for a thin physique, such as soccer players, have body image issues and disordered eating symptomatology [4]. These athletes are often thought not to have issues with body image and eating disorders, and, as a result, their symptoms go undetected. Some research suggests that female athletes may be experiencing problematic subclinical disordered eating symptoms but are not receiving treatment without this detection [2,4]. Thus, female athletes participating in nonlean sports may be especially likely to have their disordered eating symptoms go undetected.

Johnson et al. [5], conducted their investigation in collaboration with the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA), a regulatory organization that has significant influence on athletic departments [5]. They used athletes from 11 Division I schools. The authors explained that they selected athletes from the most competitive teams at prominent universities across the country because, as elite athletes, the participants may perceive that there is more to lose by engaging in disordered eating behaviors than do less elite Division II athletes. Johnson et al. [5], believed that the rate of eating disorders would be higher among less elite Division II athletes because of the possibility that Division I athletes also may have reported less symptoms to protect their schools’ athletic departments’ reputations [9]. In their study of 1,445 Division I NCAA student athletes, Johnson et al. [5], found that many female athletes reported behaviors, attitudes, and symptoms that placed them at risk of developing clinical eating disorders [5]. Results indicated that although none of the females met the DSM-IV-TR criteria for anorexia, 2.85% were identified as having symptomatology that indicated a clinically significant problem with anorexia. In addition, 1.1% met the full criteria for bulimia, and another 9.2% were identified as having a clinically significant problem with bulimia. Thus, these results revealed that many Division I NCAA female athletes do report significant symptoms of eating disorders.

The situation for Division II athletes remains unclear. Further research is needed to gather information from both Divisions I and II athletes to determine the prevalence of disordered eating symptoms reported by Division II athletes and whether there is a difference in rates of eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors reported between the less elite female athletes and the more elite female athletes [6].

Statement of the Problem

It is clear that there is a need to examine the eating behaviors of female athletes participating in “nonlean” sports, as it appears that they are less likely to show obvious visual signs of disordered eating [7]. In addition, it has been proposed that less elite athletes may be experiencing greater levels of symptomatology than more elite athletes may be experiencing [6,9]. Therefore, this study will examine the potential differences in disordered eating between NCAA Division I (more elite) and Division II (less elite) athletes who have participated in the “nonlean” sport of soccer. Such a sport is expected to be less likely to produce pressures that push female athletes toward disordered eating symptoms, but then those female athletes are less likely to be detected as exhibiting disordered eating symptoms. If, in fact, soccer as a “nonlean” sport is associated with disordered eating by female athletes, then the insidiousness of this problem will be highlighted. Furthermore, Johnson et al. explained that Division I elite athletes may perceive that there is more to lose by engaging in disordered eating behaviors than do less elite Division II athletes [6]. They further stated their belief that the rate of eating disorders would be higher among less elite Division II athletes based on the possibility that Division I athletes also may have reported less symptoms to protect their schools’ athletic departments’ reputations [6].

This study is designed to develop an increased awareness regarding disordered eating symptoms among female athletes who participate in the “nonlean sport” of soccer. Of special concern in this study are disordered eating among female athletes participating in “nonlean” sports, social physique anxiety as it is related to disordered eating among female athletes, and social pressures and women’s body image issues as they affect this population [7,10]. Those factors are believed to be of particular importance for female athletes [2,4,11,12]. The potential result of neglecting these issues among female athletes is known as The Female Athlete Triad, which consists of disordered eating, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis [10]. The information obtained from this study will help clinicians to identify the specific disordered eating behaviors that are typical of this population. Insight from the findings can then be used to create more effective recognition and prevention techniques to assist this specific group of athletes in managing their symptomatology, as well as addressing their issues with social pressures and associated anxieties [8,13,14].

Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1: Female athletes who have competed in the “nonlean” sport of soccer at Division II schools will exhibit significant symptoms of disordered eating behavior.

Hypothesis 2: Female athletes who have competed in the “nonlean” sport of soccer at Division II schools will exhibit more symptoms of disordered eating behavior than will female athletes who have competed in soccer at Division I schools

Methods

Respondents

A purposive sample of 64 female NCAA Division I and II athletes were recruited from a pool of both current and alumni soccer players from across the United States. Five of these respondents did not complete the forms sufficiently to be included in any of the data analyses. Thus, a maximum of 59 of the respondents provided data that could be used for different analyses. An attempt was made to obtain 50% Division I soccer players and 50% Division II soccer players. The final distribution turned out to be 33.9% (n = 20) Division I and 66.1% Division II (n = 39). Of the 20 Division I respondents, 12 were current players, and 8 were alumni. Of the 39 Division II respondents 23 were current players and 16 were alumni. Respondents were within the age range of 18-30 and of diverse ethnicities consisting of 78.85% (n = 41) Caucasian, 1.9% (n = 1) African American, 7.6% (n = 4) Hispanic, 3.85% (n = 2) Asian, and 7.69% (n = 4) other. The overall mean age of the respondents was 22.40. The mean age of the Alumni Division I and II athletes was 26.7 and the mean age for the Current Division I and II athletes was 19.72.

The 12 current, Division I players would be the most similar ones in this study to the participants in most of the research reviewed as those studies tended to use current, Division I players. Therefore, most of the participants in this study (alumni of both Division I and of Division II, and current, Division II players) appear to be unique to this study. In addition, Petrie et al. [14], utilized weight categories determined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in which 3.4% were classified as underweight (BMI < 18.5), 76% were considered normal weight (BMI = 18.5 to 24.9), 15.2% as overweight (BMI = 25.0 to 29.9), and 5.4% as obese (BMI > 30.0). This study found no female athletes with BMI in the obese range, 21.15% were identified as overweight, 78.84% were classified as normal weight, and none underweight. Thus, summed across Division and Status (Current and Alumni), the respondents to this study were distributed very similarly by BMI except at the two extremes. Difference found among the results may be that the sample for this study was substantially smaller and the athletes weight were self-reported without the physical examination conducted by the athletic departments.

Recruitment of Respondents

The respondents consisted of female athletes who currently play and of alumni who have previously played four years of Division I or II soccer. Approval from the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research at Argosy University, Orange County was obtained prior to collecting data. The respondents were obtained through snowball sampling. In order to obtain respondents, contacts were made to current NCAA Division I and II female soccer player rosters that were provided on University athletic websites to obtain additional respondents. A Facebook account, a social networking website, was created exclusively for the purpose of sending the instruments and to answer any questions that respondents might have regarding the survey. The names of current female soccer players were researched via Facebook. Upon matching their names and profile pictures with those on the university athletic websites, a private message was sent to those who had a Facebook account that was accessible to view. The message invited them to take the survey and to forward the survey to other current and alumni female Division I and II soccer players. In addition, the survey was sent to female individuals who the author personally knew had previously played Division I or II soccer via Facebook. They were invited to anonymously complete the survey and were requested to forward the survey to others who also met the inclusion criteria.

Measures

Demographic and Weight Questionnaire

A demographic and weight questionnaire was utilized to gather information regarding age, ethnicity, weight and height when in soccer season (which could be used to calculate the respondents’ BMI (body mass index)). In addition, questions addressed respondents’ previous athletic scholarship status, starter status, differentiation between participating as a Division I or II athlete, and current or past history of an eating disorder diagnosis and/or previous treatment.

Questionnaire for Eating Disorders Diagnosis (Q-EDD)

Respondents were asked to complete the Questionnaire for Eating Disorders Diagnosis (Q-EDD), which is a 50-item questionnaire that measures eating disorder symptoms based on the DSM-IV criteria. Previous research has indicated that this instrument is valid at identifying eating disordered symptomatology for the purpose of categorization using DSM-IV criteria and diagnoses [5,15]. Mintz, O’Halloran et al. [16], explained that respondents are placed into diagnostic categories of non- eating-disordered and eating-disordered. The eating-disordered category is made up of six specific diagnoses: Bulimia and anorexia which reflect the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria and an additional four diagnoses reflective of the DSM-IV Eating Disorder NOS descriptions: sub-threshold bulimia, menstruating anorexia, non-binging bulimia, and binge-eating disorder. The non-eating-disordered category is made up of two subcategories: asymptomatic, who have no disordered eating symptoms, and symptomatic who display symptomatic eating, but do not meet DSM-IV full diagnostic criteria.

The ATHLETE Questionnaire

In addition, respondents were invited to complete The Athlete questionnaire. Hinton & Kubas [9], Study suggested that the ATHLETE is a reliable and valid measure of the psychological factors associated with disordered eating among female athletes. Section 1 of The Athlete is a brief medical and sports history. Section 2 contains six factors that the authors found to be correlated with disordered eating behaviors: feelings about being an athlete, athlete identity, your body and sports, drive for thinness and performance, feelings about performance, performance perfectionism, support from your coach and teammates, team trust, feelings about your body and social pressure on body shape, and feelings about eating including social pressure on eating [9].

Procedures

Those female athletes who responded to the Survey-Monkey recruitment were asked to complete a computer-based survey through Survey Monkey, which is an online survey management program that allows anonymity. The survey was accessed through a link via Facebook. The private message sent through Facebook included informed consent that contained a description of the study and its purpose, a statement of confidentiality, freedom to opt-out at any time, and instructions on how to complete the online survey. All the raw data was collected and stored by the researcher through the Survey Monkey database, which is secured by a password to which only the author had access. Immediately after the respondent completed the submission of the survey, a debriefing statement was sent to the respondent with the researcher’s contact information as well as information on eating disorders including websites and help hotlines. For each current and alumni athlete who completed the survey, the author donated one dollar up to two hundred dollars total to Disabled Sports USA, whose mission is “to provide national leadership and opportunities for individuals with disabilities to develop independence, confidence, and fitness through participation in community sports, recreation and educational programs.

Results

Incidence and Significance of Respondents’ Exhibiting Eating Disorder Symptoms

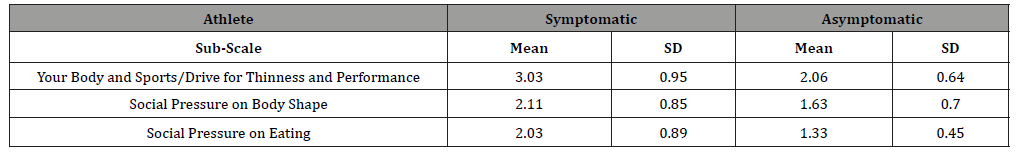

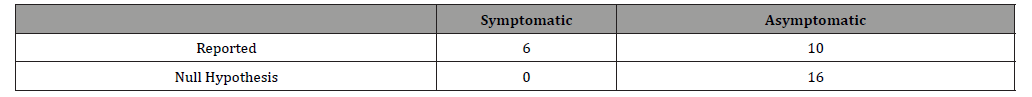

This study was concerned with the issue of eating disorders among women athletes. Consequently, the data was examined to determine the presence of eating disorders among the women athletes (Current and Alumni) who participated in this study. The presence of eating disorders was assessed through the use of the QEDD. It was found that 2 of the participants earned scores that classified them as having eating disorders in accordance with the criteria of the DSM-IV-TR. In addition, another 16 women were found to be classified as Symptomatic, and 39 of the participants were considered to be Asymptomatic. Only one of the 2 women who were classified as exhibiting an eating disorder provided data that could be used for the following analyses. Thus, this woman was combined with the Symptomatic group for the following analyses. Thirty-nine respondents who were classified as Asymptomatic provided sufficient data to be included in the following analyses. The obtained distribution of Symptomatic vs. Asymptomatic respondents can be seen in the top row of Table 1.

Table 1:Test of Null Hypothesis that female soccer player respondents do not report symptoms of eating disorders. Chi Square = 20.042.

It can be seen that just over 30 % of the respondents were classified as Eating Disorder or Symptomatic. In order to assess the meaningfulness of this finding, the distribution of Symptomatic v. Asymptomatic respondents was assessed against a null hypothesis that none of the respondents would be classified as Symptomatic. Consequently, a Chi-square test was computed (Chi Square (1df) = 20.042, p = .001). This result indicates that the finding that 17 of the 56 Current and Alumni athletes were found to be symptomatic for eating disorders is not an insignificant numerical finding. Thus, over 30% of the women athletes who participated in this study are exhibiting symptoms of an eating disorder.

Relationship of Symptomatic Classification to the ATHLETE Sub-scales

ANOVAs were then computed to determine whether women classified as Symptomatic scored differently compared to women classified as Asymptomatic on any of the sub-scales of the ATHLETE Scale. No significant differences were found for the 3 subscales of: Feelings about Being an Athlete, Athlete Identity; Feelings about Performance, Performance Perfectionism; Support from your Coach and Teammates, Team Trust.

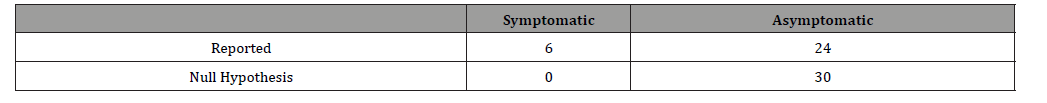

Significant differences were obtained for the following 3 ATHLETE sub-scales: Your Body and Sports, Drive for Thinness and Performance (F (1, 46), p = .001); Feelings About Your Body, Social Pressure on Body Shape; (F (1, 46), p = .004); and for Feelings About Eating, Social Pressure on Eating (F (1, 46), p = .008). Means and Standard Deviations for Symptomatic and Asymptomatic women are presented in Table 2. It can be seen that on all three of these measure, Symptomatic women obtain higher mean scores indicating greater concerns than endorsed by Asymptomatic women about their body in their sport, their body in general, and in regard to their eating habits.

Table 2:Means and Standard Deviations for the 3 Significant ATHLETE Sub-scales Differentiating Symptomatic from Asymptomatic Women.

Relationship of Symptomatic Status to Division Played and Current vs. Alumni Status

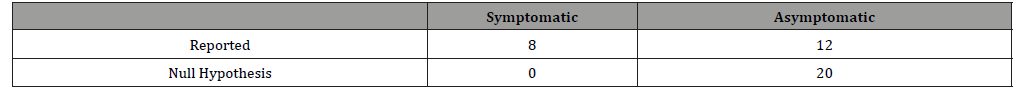

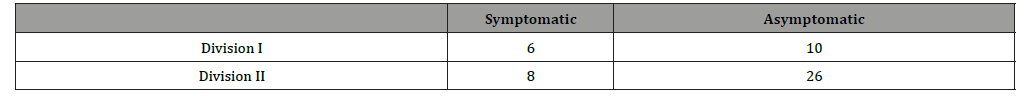

Next, an effort was made to determine whether the incidence of Symptomatic eating disordered behavior found in this study was differentially associated with respondent status (Current or Alumni) or Division played (I or II). First, the distribution of Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Current players was assessed against a null hypothesis that none of these respondents would be classified as Symptomatic (Table 3). A chi-square goodness-of-fit test (Chi Square (1 df) = 6.67, p = .01) was significant. This result indicates that 6 of the 30 Current athletes were found to be symptomatic for eating disorders. This not an insignificant numerical finding as this is not a chance difference from none.

Table 3:Test of the Null Hypothesis that Current soccer players do not report symptoms of eating disorders. Chi Square = 6.67

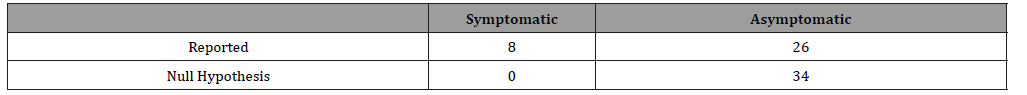

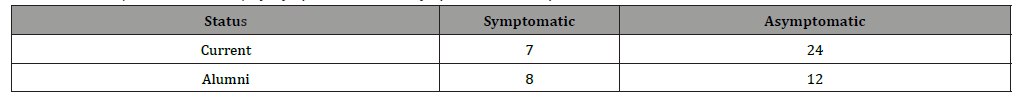

Similarly, the fact that 8 of the 20 Alumni soccer players who responded to this survey were classified as Symptomatic was also tested against a null hypotheses that none of these women would be so classified. The result of that analysis (Chi Square (1 df) = 10.0, p = .01) was significant, indicating that the fact that 8 of these 12 women were classified as Symptomatic is a meaningful numerical finding (Table 4).

Table 4:Test of the Null Hypothesis that Alumni female soccer players do not report symptoms of eating disorders. Chi Square = 10.0

Next, the fact that 8 of the 34 Division II soccer players who responded to this survey were classified as Symptomatic was also tested against a null hypothesis that none of these women would be so classified. The result of that analysis (Chi Square (1 df) = 9.067, p = .01) was significant, indicating that the fact that 8 of these 26 women were classified as Symptomatic is a meaningful numerical finding (Table 5).

Table 5:Test of the Null Hypothesis that Division II female soccer players do not report symptoms of eating disorders. Chi Square = 9.067

Table 6:Test of the Null Hypothesis that Division I female soccer players do not report symptoms of eating disorders. Chi Square = 7.385

Finally, the finding that 6 of the 16 Division II soccer players who responded to this survey were classified as Symptomatic was also tested against a null hypotheses that none of these women would be so classified. The result of that analysis (Chi Square (1 df) = 7.385, p = .01) was significant, indicating that the fact that 6 of these 16 women were classified as Symptomatic is a meaningful numerical finding (Table 6).

In order to assess whether there was a relationship between playing Division I rather than Division II was differentially related to being symptomatic, a Chi-square test was conducted. It yielded a value of 1.0533, which is not significant (Table 7). This finding indicated that Division played was not significantly related to whether the athlete was classified as symptomatic.

The relationship of the athlete’s status (Current vs. Alumni) to being symptomatic was also assessed by Chi-square. The resultant value of 1.777 was not significant (Table 8). Thus, whether the respondent was a Current player or an Alumnus was not related to being symptomatic.

Table 7:Test of Hypothesis 2 that Division I female soccer players will not report more disordered eating than Division II female soccer players. Chi Square = 1.0533

Table 8:Status (Current v. Alumni) by Symptomatic v. Non-symptomatic. Chi Square = 1.777

Relationships of Status and Division to the ATHLETE SUB-SCALES

In order to assess the relationships of Player Status (Current vs. Alumni) and Division played (Division I vs. Division II) to the subscales of the ATHLETE instrument, ANOVAS were conducted with each of the 6 sub-scales of the ATHLETE as dependent variables. The only significant finding was for Division I vs. Division II on the Feelings about Being an Athlete, Athlete Identity sub-scale (F (1, 43) = 6.744. p = .013. This finding is presented in Figure 1. It can be seen that there was no meaningful difference in the scores on this scale for Division I compared to Division II Alumni. However, Division II Current players exhibited a significantly higher endorsement of the importance of being an athlete to their identity. Division I Current (M = 2.756), Alumni (M= 2.354); Division II Current (M = 3.237), Alumni (M = 2.354). There was a statistically significant difference at the p< .05 level in the athlete identity scores between Division II Current vs. Alumni players. This indicates that Division II current female athletes identify more strongly with being an athlete than do Division I current female soccer players. It can also be seen that post collegiate career, both Division I and II female soccer players experience a decline in identifying as an athlete, and in fact identify to the same lower degree at some point after leaving the sport.

Although there were no other statistically significant differences related to Divisions and Status of the participant (Current or Alumni), the means are presented graphically as they suggest that there may be effects that did not reach statistical significance in this study, but require further research. Figure 2 presents the means for the Sub-scale of Feelings about Performance and Performance Perfectionism.

The analysis for the ATHLETE Sub-scale of Support from your Coach and Teammates, Team Trust is presented in Figure 3. No statistically significant differences were obtained for this variable. However, it appears that Division I and Division II Current women soccer players are quite similar, but when they become Alumni, their feelings about the importance of support from their coaches and teammates goes in opposite directions. This effect did not quite reach conventional levels of statistical significance (F (1,47) = 2.834, p = .099). Again, the small n in some of the cells may be making this comparison insensitive. This possible effect contrasts for the possible effect seen for importance of athlete identity, which appears to decrease for both Division I and II players when they leave the sport, but possibly the importance of their coaches and teammates at that point in their lives has a different significance.

If the above interaction is indeed a real phenomenon, then it indicates that Current Division I female soccer players endorse feeling more support from their coaches and teammates than do Division II current female soccer players. In contrast, Alumni Division II female soccer players reported feeling additional support post collegiate soccer career from their coaches and teammates, here as Alumni Division I athletes reported experiencing a decrease in support. The Alumni Division II females reported support that exceeded the Current Division I soccer players.

The remaining 3 sub-scales of the ATHLETE also did not reflect statistically significant differences between either the Divisions nor between Status of being a Current player or being an Alumni. However, an examination of Figures 4-6 reveals a consistent pattern of Division II players, both Current and Alumni reporting greater con cerns than Division I players on these variables. In addition, there is no overlap of any of these classifications of women soccer players on any of these variables. Once again, these Figures are provided for their implications for future research and will be considered more fully in the Discussion section.

In regard to the sub-scale: Feelings About Your Body, Social Pressure on Body Shape, the data obtained here suggest that both Division I and II female soccer players experienced an increase in endorsements of social pressure relative to body shape when they became Alumni. Division II female soccer players endorsed notably higher rates in both the Current athletes as well as the Alumni athletes when compared to Division I females. Although these differences were not statistically significant, with a greater sample size, this pattern of results may have reached levels to support the hypothesis that Division II female soccer players experience higher rates of disordered eating and body image issues compared to Division I female soccer players.

Results indicated that Hypothesis One was supported in that female athletes who have competed in the “non-lean” sport of soccer at Division II schools exhibited symptoms of eating disordered behavior and endorsed trends congruent with body image issues. Eight of the 34 Division II soccer players who responded to this survey were classified as Symptomatic. When tested against a null hypothesis that none of these women would be classified as symptomatic; the result of that analysis (Chi Square (1 df) = 9.067, p = .01) was significant, indicating that the fact that 8 of these 26 women were classified as Symptomatic is a meaningful numerical finding (Table 5).

Regarding the second hypothesis, Division II female soccer players endorsed trends regarding poor body image and disordered eating behaviors on the Athlete questionnaire that indicated that these females exhibit greater body image concerns when compared to more elite Division I female athletes’ responses. In order to assess whether there was a relationship between playing Division I rather than Division II was differentially related to being symptomatic, a Chi-square test was conducted. It yielded a value of 1.0533, which is not significant (Table 7). This finding indicated that Division played was not significantly related to whether the athlete was classified as symptomatic. However, 10 of the 46 female soccer players who completed the Athlete Questionnaire also completed the QEDD and endorsed disordered eating behaviors and body image responses that warranted them being placed in the symptomatic category.

Discussion

Incidence Rates of Disordered Eating

The main purpose of this study was to develop an increased awareness regarding disordered eating symptoms and body image issues among female athletes who participate in the “nonlean” sport of soccer. A purposive sample of 64 female NCAA Division I and II athletes was recruited from a pool of both current and alumni soccer players from across the United States. Because some of the respondents did not complete all of the data sheets, the number available varies in different analyses. The final distribution turned out to be 28.85% Division I and 71.15% Division II. Of the Division I respondents, 75% were current players, and 25% were alumni. Of the Division II respondents, 57% were current players, and 43% were alumni. The mean age of the respondents was 20.38 years, and they were of diverse ethnicities, consisting of 78.85% (n = 41) Caucasian, 1.9% (n = 1) African American, 7.6% (n = 4) Hispanic, 3.85% (n = 2) Asian, and 7.69% (n = 4) other. Previous research pulled from a similar sample in that the mean age was 20.16 years and predominantly consisted of Caucasian females, followed by Hispanic, African American, Asian American/Pacific Islander, and American Indian, with 4.4% identifying as “other.” [4]

Data were examined to determine the presence of eating disorders among the women athletes who participated in this study. The presence of eating disorders was assessed through the use of the Questionnaire for Eating Disorders Diagnosis (QEDD). It was found that two of the participants had scores that classified them as having eating disorders in accordance with the criteria of the DSMIV- TR. Sixteen women were found to be classified as symptomatic, and 39 of the participants were considered to be asymptomatic. Only one of the two women who were classified as exhibiting an eating disorder provided data that could be used for the following analyses. Due to the low number of respondents who met the criteria for eating disorders, this study combined the eating disorder group and the symptomatic group as one prior study had done [4]. Thirty-nine respondents who were classified as asymptomatic provided sufficient data to be included in the analyses. Greenleaf et al. reported results indicating that over one fourth of the female athletes were identified as symptomatic or as having eating disorders [4]. In addition, Petrie et al. [17], reported results based on QEDD responses that indicated 72.5% of female athletes were considered asymptomatic, 25.5% symptomatic, and 2% eating disordered, a 27.5% total when the authors combined the symptomatic and eating disordered groups [17]. This study identified 30% as symptomatic, a slightly higher percentage of female soccer players who endorsed items that suggested they were symptomatic or eating disordered than did the Greenleaf et al. and the Petrie et al. studies [4,16]. Thus, this study found results similar to the earlier studies in that 70% were categorized as asymptomatic, and 30% of the female soccer players who responded to the QEDD indicated that they were symptomatic or eating disordered.

The distribution of symptomatic v. asymptomatic respondents was assessed against a null hypothesis that none of the respondents would be classified as symptomatic. Consequently, a Chi-square test was computed [Chi-Square (1df) = 20.042, p = .001]. This finding indicated that a very significant portion of the 56 current and alumni athletes who participated in this study were found to be symptomatic for eating disorders. Thus, this study found a substantial number of female athletes to be symptomatic of an eating disorder, as have earlier studies.

However, it is also the case that the percentage of participants in this study who were classified as exhibiting symptoms of an eating disorder is the highest reported to date. As was speculated earlier, it was considered possible that this study would obtain a higher rate of female athletes exhibiting symptoms of an eating disorder if the women in the earlier, NCAA sponsored studies were underreporting their symptoms. Of course, it is also possible that this study especially attracted women athletes who exhibit symptoms of an eating disorder.

In addition, the present study included women athletes who were not assessed in the earlier studies; thus, this study has a wider range of athletes than prior studies did. Consequently, this study provides data on women athletes not previously studied. For example, this study included Division II athletes, of which 23.5% were classified as symptomatic, whereas 37.5% of the Division I athletes were classified as symptomatic in this study these percentages clearly exceed the rates reported in earlier studies. Implications of this finding will be discussed in a later section. This study also included alumni.

It was found that (summed across divisions) 22.5% of the current players were classified as symptomatic, a percentage very close to that reported in the earlier studies. However, 40% (8 of 20) of the alumni who participated in this study were classified as symptomatic. While this is a small number of alumni women athletes, this finding strongly suggests that there is a sizeable portion of former women athletes who have to deal with symptoms of an eating disorder when their athletic careers are over.

Relationship of ATHLETE Scale to Symptoms of Disordered Eating

Next, an effort was made to determine whether the ATHLETE Scale could help differentiate sources of distress for the women classified as symptomatic. ANOVAs were then computed to determine whether women athletes classified as symptomatic scored differently than women athletes classified as asymptomatic on any of the subscales of the ATHLETE Scale. Significant differences were found for three of the six subscales. No significant differences were found for the following three subscales: Feelings about Being an Athlete, Athlete Identity; Feelings about Performance, Performance Perfectionism; and Support from Your Coach and Teammates, Team Trust. These nonsignificant findings suggest that these scales may not be as sensitive at pulling for disordered eating and body image issues among this population, or possibly, these findings show that these are not relevant issues for women athletes with regard to vulnerability for being symptomatic of an eating disorder.

Significant differences were obtained for the following three ATHLETE subscales: (a) Your Body and Sports, Drive for Thinness and Performance [F (1, 46), p = .001]; (b) Feelings about Your Body, Social Pressure on Body Shape; [F (1, 46), p = .004]; and (c) Feelings about Eating, Social Pressure on Eating [F (1, 46), p = .008]. It can be seen that on all three of these subscales, symptomatic women obtained higher mean scores, indicating greater concerns than were endorsed by asymptomatic women about their body in their sport, their body in general, and their eating habits. These significant findings indicate that these scales are helpful in identifying risk factors for female soccer players who might be struggling with disordered eating and body image issues. These findings will be further analyzed when the clinical implications and recommendations are discussed.

Relationship of Status and Division to Disordered Eating Symptoms

Next, analyses were conducted to determine whether the status (current or alumni) of division played (I or II) was more likely than not to be associated with being classified as symptomatic. Since prior studies focused on current athletes, the distribution of symptomatic and asymptomatic current players in this study was assessed against a null hypothesis that none of these respondents would be classified as symptomatic. A Chi-square goodness-of-fit test [Chi- Square (1 df) = 6.67, p = .01] was significant. This result indicated that the fact that six of the 30 current athletes (20%) were found to be symptomatic for eating disorders is a significant numerical finding as this is not a chance difference from none. Thus, these results are consistent with the earlier results with larger sample sizes obtained by Greenleaf et al. [4], who reported one fourth of their participants were classified as symptomatic, and Petrie et al. [17] who found that 27.5% of their Division I women athletes were classified as exhibiting symptoms of an eating disorder.

Similarly, eight of the 20 alumni soccer players who responded to this survey were classified as symptomatic, and this distribution was also tested against a null hypothesis that none of these women would be classified as symptomatic. The result of that analysis [Chi- Square (1 df) = 10.0, p = .01] was significant, indicating that the fact that eight of these 20 women were classified as symptomatic is a meaningful numerical finding. As indicated earlier, the fact that 40% of the alumni women soccer players who chose to participate in this study were found to be symptomatic of an eating disorder raises serious questions about what is happening to these women when they leave the sport. Even if this study pulled a disproportionate percentage of these women to the study, the fact remains that, for the first time, there are data that indicate that issues of disordered eating for women athletes after they have fulfilled their college career need to be addressed. Possibly, the past focus on current players has missed the mark in the sense that issues of disordered eating that might be under the surface during the women’s playing careers may not become apparent (at least for many of the women) until their careers are over. Possibly one manifestation of this is the finding that these women’s identification with being an athlete (Feelings about Being an Athlete, Athlete Identity) apparently decreases when they leave the sport; however, now the constraints on their eating disorder are also lost. Thus, we have a large percentage of these alumni now classified as symptomatic of an eating disorder. One might also consider that disordered eating and poor body image may be issues that many alumni females struggle with post career in part due to the natural aging process that includes a lower metabolism. One may consider that this study did not include females over the age of 30 years; however, older alumni female athletes may reveal greater struggles with these issues than this young sample of alumni, especially in this society that places such a high value on appearing youthful through means of extreme dieting and exercise, Botox, and surgical procedures.

This study was especially interested in extending the research to Division II women athletes. Eight of the 34 Division II soccer players who responded to this survey were classified as symptomatic; this finding was also tested against a null hypothesis that none of these women would be so classified. The result of that analysis [Chi-Square (1 df) = 9.067, p = .01] was significant, indicating that the finding that eight of these 34 women (23.5%) were classified as symptomatic is a meaningful numerical finding and supports the first hypothesis of this study that Division II female soccer players would be found to struggle with disordered eating and body image issues. It should also be noted that this percentage of 23.5% for the “nonlean” sport of soccer is very similar to what prior studies found for Division I women athletes summed across “lean” and “nonlean” sports.

Finally, the finding that six of the 16 Division I soccer players (37.5%) who responded to this survey were classified as symptomatic was also tested against a null hypothesis that none of these women would be so classified. The result of that analysis [Chi- Square (1 df) = 7.385, p = .01] was significant, indicating that the finding that six of these 16 women were classified as symptomatic is a meaningful numerical finding. Thus, all of the above analyses indicated that, however the participants were classified (status, division), the percentages classified as symptomatic of an eating disorder were significant, nontrivial percentages.

In order to assess if playing Division I rather than Division II was differentially related to being symptomatic, a Chi-square test was conducted. It yielded a value of 1.0533, which is not significant (Table 7). This finding indicated that the division played was not significantly related to whether the athlete was classified as symptomatic. This does not support the second hypothesis, as Division II athletes were not found to be more prone to disordered eating than Division I female soccer players were.

The relationship of the athlete’s status (current vs. alumni) to being symptomatic or not was also assessed by Chi-square. The resultant value of 1.777 was not significant. Thus, whether the respondent was a current player or an alumnus, was not differentially related to being symptomatic. This indicates that whether or not the woman athlete has the current stress of performance or association with a team does not play a significant factor in her report of eating disorder symptomatology.

Relationship of Status and Division to the ATHLETE Subscales

In order to assess the relationships of player status (current vs. alumni) and division played (Division I vs. Division II) to the subscales of the ATHLETE instrument, ANOVAS were conducted with each of the six subscales of the ATHLETE as dependent variables. The only significant finding was for Division I vs. Division II on the Feelings about Being an Athlete, Athlete Identity subscale [F (1, 43), = 6.744. p = .013]. It can be seen from Figure 1 that there was no meaningful difference in the scores on this scale for Division I compared to Division II alumni. However, Division II current players exhibited a significantly higher endorsement of the importance of being an athlete to their identity: Division I Current (M = 2.756), Alumni (M= 2.354); Division II Current (M = 3.237), Alumni (M = 2.354). There was a statistically significant difference at the p< .05 level in the athlete identity scores between Division II current vs. alumni players. This indicates that Division II current female athletes identify more strongly with being an athlete than do Division I alumni female soccer players, and Division II current players scored the highest on this measure of importance of identifying with being an athlete. It can also be seen that post collegiate career, both Division I and II female soccer players experience a decline in identifying as an athlete and, in fact, identify to the same lower degree at some point after leaving the sport. The finding that the current Division II players have the greatest reported importance of their identification with being an athlete is a unique finding. Possibly, women who can achieve Division I status have more resources, abilities, and attributes with which they formulate their identities than do Division II players. Possibly, this finding is a form of cognitive dissonance for the Division II players who do not/cannot achieve Division I status. Possibly the Division II players are communicating their disappointment at not being able to achieve Division I status as they express greater importance of their identity as an athlete (while still playing) than do the other women, but they are not able to obtain the higher playing status. One wonders if those who score the highest on this athlete identity variable are also more at risk to be alumni who are symptomatic of an eating disorder. Obviously, this will be a fertile area for further research.

Furthermore, it may be beneficial to explore what specific factors female athletes consider when they endorse a high level of athlete identity. Is an athletic physique that may be hard for many to maintain post athletic career highly correlated with their identity?

The analysis for the ATHLETE subscale of Support from Your Coach and Teammates, Team Trust indicated no statistically significant differences were obtained for this variable. However, it appears that Division I and Division II current women soccer players are quite similar, but when they become alumni, their feelings about the importance of support from their coaches and teammates go in opposite directions. This effect did not quite reach conventional levels of statistical significance [F (1, 47) = 2.834, p = .099]. Specifically, it can be seen in Figure 3 that Division II players may be reporting that after they finish their careers, they experience the importance of support from their coaches and teammates as more important than when they played. Again, the small n in some of the cells may be making this comparison insensitive to a real phenomenon. It is interesting to note that, in contrast to the importance of athlete identity, which appears to decline for both Division I and II players after they leave the sport, the Division II alumni report that the support of coaches and teammates is more important now than it was during their playing days. The Division I alumni, in contrast to Division II alumni, reported no such phenomenon.

The remaining three subscales of the ATHLETE also did not reflect statistically significant differences between the divisions or between status of being a current player or an alumnus player. However, an examination of Figures 4-6 revealed a consistent pattern of Division II players, both current and alumni, reporting greater concerns than Division I players on these variables. In addition, there is no overlap of any of these classifications of women soccer players on any of these variables. These results suggest that despite Division II female athletes feeling more supported by their coaches and teammates than Division I females do, the Division II individuals reported struggling more with a drive to be thin and social pressures with eating. This further indicates that social support is not necessarily a completely protective measure, nor does it help with the prognosis of disordered eating and body image issues with this population.

With regard to the subscale, Feelings about Your Body, Social Pressure on Body Shape, the data obtained here suggest that both Division I and II female soccer players experienced an increase in endorsements of social pressure relative to body shape when they became alumni. Division II female soccer players, current and alumni, endorsed higher rates than Division I women. Although these differences were not statistically significant, the pattern of results suggests potential trends that may support the hypothesis that Division II female soccer players experience higher rates of disordered eating and body image issues than Division I female soccer players do; therefore, more sensitive designs, sample sizes, and/or measures need to be conducted. The less elite league, Division II, likely allows for less rigorous workouts that may result in athletes feeling less content with their physique when compared to the Division I athletes whose rosters are more competitive and whose athletes are often given the luxury of more advanced training facilities, access to physical trainers, dietitians, and other resources.

These results suggest that current Division I and II female soccer players experience less drive for thinness than do the alumni respondents in both divisions. Data suggested a similar trend for the subscales Feelings about Your Body, Social Pressure on Body Shape; and Feelings about Eating, Social Pressure on Eating. Division II female athletes endorsed a higher level of drive for thinness than Division I female soccer players did regardless of status of being current or alumni. This pattern (although not statistically significant) has the potential to support this study’s hypothesis that less elite Division II female soccer players struggle with factors relative to disordered eating and body image to a greater degree than do Division I female soccer players, so further research also needs to be conducted to determine whether the pattern found here is, in fact, a reliable finding.

Results indicated that Hypothesis 1 was supported in that female athletes who have competed in the “nonlean” sport of soccer at Division II schools exhibited symptoms of disordered eating behavior and endorsed trends congruent with body image issues found previously with Division I women athletes. Eight of the 34 Division II soccer players who responded to this survey were classified as symptomatic, which is an incidence rate very similar to what has been reported for Division I athletes [4,17].

Several investigators had suggested that symptoms of disordered eating would be more prevalent among Division II athletes than among Division I athletes, which was the foundation for Hypothesis 2. Regarding the second hypothesis, Division II female soccer players endorsed trends regarding poor body image and disordered eating behaviors on the ATHLETE questionnaire that indicated that these women exhibit greater body image concerns when compared to more elite Division I female athletes (Tables 6&7). Chisquare tests were conducted in order to assess whether there was a relationship between playing Division I rather than Division II to being symptomatic. The result was not significant. This finding indicated that division played was not significantly related to whether the athlete was classified as symptomatic. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was not supported by this finding.

Although there were no other statistically significant differences related to division and status of the participant (current or alumni), the means are presented graphically as they suggest that there may be effects that did not reach statistical significance in this study but require further research (Figures 4-6) and should not be dismissed because of the statistically nonsignificant findings of this study. It can be seen that there was a consistent pattern that these women scored highest of all the participants on measures assessed by the following subscales: Your Body and Sports, Drive for Thinness and Performance; Feelings about Your Body, Social Pressure on Body Shape; and Feelings about Eating, Social Pressure on Eating. Thus, there were numerous indications in this study that Division II women soccer players are at greater risk for symptoms of disordered eating than are Division I players and that some of the factors affecting them pertain to the following subscales: Your Body and Sports, Drive for Thinness and Performance; Feelings about Your Body, Social Pressure on Body Shape; and Feelings about Eating, Social Pressure on Eating. Consequently, additional research is needed to further assess this possibility.

Incidence of Full Eating Disorder Diagnosis

The results from this study did not indicate that any of the female athletes endorsed symptoms that would meet the full DSMIV criteria for anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa; however, two of the women did indicate that they were experiencing symptoms that would warrant a diagnosis of eating disorder not otherwise specified. The QEDD categorized one of these women as having met criteria for non-binging bulimia and categorized the other female as having met criteria for subthreshold bulimia. In addition, 27.8% of the female athletes were considered symptomatic, and this number was higher than what previous research reported. Johnson et al. [5], Previously reported finding 12.05% of Division I females to be at risk for developing anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. Additionally, Johnson et al. reported 10.85% of females who admitted to binge eating a minimum of once per week and 5.5% of females who reported purging behaviors (vomiting, laxatives, diuretics) on a weekly or greater basis.

The findings of this study and of the studies by Petrie et al. [17], and Greenleaf et al. [6] suggest that female athletes have become more symptomatic over the last decade, when compared with the findings of Johnson et al. [10], due to a variety of possible variables. In 1999, Johnson et al. [5], reported 2.85% as symptomatic and at risk for developing anorexia, while 1.1% met criteria for bulimia, and another 9.2% were identified as having clinically significant problems with bulimia. Standford et al. [15], reported a disordered eating symptom rate of approximately 14%-19%. In contrast, as previously reported, Petrie et al. [17], indicated 25.5% were symptomatic and 2% eating disordered, and Greenleaf et al. [6], also reported that over one fourth of the female athlete respondents were identified as symptomatic or as having eating disorders. The present study found a slightly higher rate of 30% when including Division II and alumni players. Thus, it is possible that the overall rate of disordered eating and poor body image among female athletes has risen over the last decade. It may also be possible that prevalence rates are higher among female soccer players compared to women in other sports that were utilized in previous studies. Athletes from this study were exclusively female soccer players who were currently playing or had played at the NCAA Division I or II collegiate level, and multiple variables may have contributed to the higher percentage of those categorized as having disordered eating symptomatology. However, the above previous studies reported results that suggest there has been an increase in disordered eating symptomatology reported by female athletes [18-22].

Limitations and Implications for Future Research

There were a few demographic limitations to this study. Although the authors attempted to obtain an equal number of respondents in each of the four groups—Current Division I, Alumni Division I, Current Division II, and Alumni Division II—the sample was small relative to the study’s design. This created a limitation in the statistical analyses that were able to be conducted and find meaningful results. In addition, many of the athletes who responded to the survey were Caucasian, and although the sample mirrored that of previous research, these results do not contribute to a further understanding of disordered eating across ethnicities.

The author wanted to obtain a sample without having to utilize the NCAA or University IRBs in an attempt to avoid the pressures that were possibly placed on athletes who have previously participated in similar studies. Because of this, new limitations became evident as the author attempted to obtain the sample by viewing public rosters of current athletes via university websites and then through recruiting the respondents by sending private Facebook messages to them and inviting them to complete an online survey involving disordered eating and body image. Possibly due to the methodology used in this study, these respondents may not have felt pressure to withhold from reporting their symptomatology for fear of possible ramifications from their universities, coaches, or the NCAA for representing or reflecting poorly on their athletic programs [23-25].

The ATHLETE Questionnaire revealed results that would benefit from future research. One of these findings was that current Division II players have the greatest reported importance of their identification with being an athlete, and this was one of the statistically significant findings in this study (Figure 1). One might wonder what contributing factors play into an athlete endorsing this subscale to such a high degree and if those who score the highest on this athlete identity variable are also more at risk to be alumni who are symptomatic of an eating disorder. Identifying this as a potential risk factor may allow university staff members to help individuals combat such symptomatology by asking questions related to this subscale that are less face-valid than other subscales and instruments are. It would be beneficial in identifying those who struggle with eating disordered symptomatology to determine if there is a significant correlation between this subscale and others with eating disorder diagnosis as defined by the DSM-IV-TR.

Additionally, Figure 3 illustrates that Division II players are reporting that after they finish their athletic careers, they experience the importance of support from their coaches and teammates as more significant than when they played. Again, the small n in some of the cells may be making this comparison insensitive to a real phenomenon. It is interesting to note that, in contrast to the importance of athlete identity, which appears to decline for both Division I and II players after they leave the sport, the Division II alumni report that the support of coaches and teammates is more important now than it was during their playing days. The Division I alumni, in contrast to Division II alumni, reported no such phenomenon. Seemingly this would suggest that social support, although important to Division II athletes, is not sufficient in helping them to overcome disordered eating and poor body image trends.

The means were presented graphically as they suggest that there may be effects that did not reach statistical significance, but that require further research (Figures 1-6). Thus, there were numerous indications that Division II women soccer players are at greater risk for symptoms of disordered eating than are Division I players with regard to Athlete Identity, Performance Perfectionism, and Team Trust. Consequently, additional research is needed to further assess this possibility. The pattern of results support the hypothesis that Division II female soccer players experience higher rates of disordered eating and body image issues than do Division I female soccer players. Results indicated that current Division I and II female soccer players experience less drive for thinness than the alumni respondents in both divisions. The Division II players both current and alumni endorsed higher levels of distress relative to a drive to be thin than did Division I females. This pattern (although not statistically significant) further supports this study’s hypothesis that less elite Division II female soccer players struggle with factors relative to disordered eating and body image to a greater degree than do Division I female soccer players. This deserves further research [26,27].

Conclusion

Future research identifying preventative measures and effective treatment modalities would greatly benefit these female athletes who silently endure problematic symptomatology. This study used self-report measures exclusively, and future research would likely benefit from utilizing a structured interview to obtain further information from the athletes as well as interviewing family members and access to physicians’ records to ensure that the athletes are reporting an accurate account of their weight and behaviors. A larger sample size of female soccer players would allow more specific and detailed analysis of trends that correlate with specific disordered eating and poor body image issues. University and high school athletic programs would benefit from administering a standard battery of measures and interviews when students enter an athletic program to ensure that coaches, athletic trainers, and parents are made aware of the risk factors and are able to help female athletes who struggle with these issues.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- Beals KA, Manore MM (2000) Behavioral, Psychological, and Physical Characteristics of Female Athletes With Subclinical Eating Disorders. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism 10(2): 128-143.

- Bissell KL (2004) Sports Model/Sports Mind: The Relationship Between Entertainment and Sports Media Exposure, Sports Participation, and Body Image Distortion in Division I Female Athletes. Mass Communication & Society 7(4): 453-473.

- Crago M, Yates A, Beutler LE, Arizmendi TG (1985) Height-Weight Rations Among Female Athletes: Are Collegiate Athletics the Precursors to an Anorexic Syndrome? International Journal of Eating Disorders 4(1): 79-87.

- Davis C, Strachan S (2001) Elite Female Athletes with Eating Disorders: A Study of Psychopathological Characteristics. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 23: 245-253.

- Johnson C, Powers PS, Dick R (1999) Athletes and Eating Disorders: The National Collegiate Athletic Association Study. International Journal of Eating Disorders 26(2): 179-188.

- Greenleaf C, Petrie TA, Carter J, Reel JJ (2009) Female Collegiate Athletes: Prevalence of Eating Disorders and Disordered Eating Behaviors. Journal of American College Health 57(5): 489-495.

- Hausenblas HA, Carron AV (1999) Eating Disorder Indices and Athletes: An Integration. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology 21: 230-258.

- Hausenblas HA, Mack DE (1999) Social Physique Anxiety and Eating Disorder Correlates Among Female Athletic and Nonathletic Populations. Journal of Sport Behavior 22(4): 502-512.

- Hilton PS, Kubas KL (2005) Psychological Correlates of Disordered Eating in Female Collegiate Athletes: Validation of the ATHLETE Questionnaire. Journal of American College Health 54(3): 149-156.

- Hornak NJ, Hornak JE, Cappaert TA (2004) The Athletic Trainer and Eating Disorders: Part I, Recognition and Prevention. Athletic Therapy Today 9(3): 42-43.

- Kakaiya D (2008) Eating Disorders Among Athletes. IDEA Fitness Journal: 44-51.

- Krane V, Waldron J, Stiles Shipley JA, Michalenok J (2002) Relationships Among Body Satisfaction, Social Physique, and Eating Behaviors in Female Athletes and Exercisers. Journal of Sport Behavior 24(3): 247-264.

- Malinauskas B, Cucchiara A, Aeby V, Bruening C (2007) Psychical Activity Disordered Eating Risk, and Anthropometric Measurement: A Comparison of College Female Athletes and Non-Athletes. College Sudent Journal 41(1): 217-222.

- Petrie TA, Greenleaf C, Reel J, Carter J (2009) Personality and Psychological Factors as Predictors of Disordered Eating Among Female Collegiate Athletes. Eating Disorders 17 (4): 302-321.

- Stanford Martens TC, Davidson MM, Yakushko OF, Martens MP, Hinton P, et al. (2005) Clinical and Subclinical Eating Disorders: An Examination of Collegiate Athletes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 17: 79-86.

- Mintz BL, O Halloran MS, Mulholland AM, Schneider PA (2007) Questionnaire for Eating Disorder Diagnoses: Reliability and validity of operationalizing DSM-IV criteria into a self-report format: Correction. Journal of Counseling Psychology 44(2): 63-79.

- Reel Soo Hoo, Petrie Greenleaf, Carter (2010) Slimming Down for Sport: Developing a Weight Pressures in Sport Measure for Female Athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 4: 99-111.

- Muscat AC, Long BC (2006) Critical Comments About Body Shape and Weight: Disordered Eating of Female Athletes and Sport Participants. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 20: 1-24.

- Manore MM, Kam LC, Loucks AB (2007) The female athlete triad: Components, nutrition issues, and health consequences. Journal of Sports Sceinces 25(S1): 61-71.

- Pavlidou M, Doganis G (2007) Eating Disorders in Female Athletes: A Literature Review. Studies in Physical Culture and Tourism 14: 125-130.

- Powers PS (1999) Athletes and Eating Disorders. Eating Disorders 7: 249-255.

- Schwarz HC, Gairrett RL, Aruguete MS, Gold ES (2005) Eating Attitudes, Body Dissatisfaction, and Perfectionism in Female College Athletes. North American Journal of Psychology 7(3): 345-352.

- Sherman RT, Thompson RA, Dehass D, Wilfert M (2005) NCAA Coaches Survey: The Role of the Coach in Identifying and Managing Athletes with Disordered Eating. Eating Disorders 13 (5): 447-466.

- Simpson WF, Hall HL, Coady RC, Dresen M, Ramsay JD, et al. (1998) Knowledge and attitudes of university female athletes about the female athlete triad. Journal of Exercise Physiology 1(1).

- Smolak L, Murnen SK, Ruble AE (2000) Female Athletes and Eating Problems: A Meta-Analysis. Eating Disorders 27(4): 371-380.

- Waldron JJ, Krane V (2005) Whatever it Takes: Health Compromising Behaviors in Female Athletes. Quest 57: 315-329.

- Williamson DA, Netemeyer RG, Jackman LP, Anderson DA, Funsch CL, et al. (1995) Structural Equation Modeling of Risk Factors for the Dvelopment of Eating Disorder Symptoms in Female Athletes. International Journal of Eating Disorders 17(4): 387-393.

-

Samantha Lussier, Stephen E. Berger, Bina Parekh. Disordered Eating and Body Image Among NCAA Division I and II Female Soccer Players. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 4(2): 2020. OAJAP.MS.ID.000583.

Body Image, Eating Disorders, Female Soccer Players, Approximately, Diagnosed, Physique Revealing, Bulimia, Symptomatology, Hausenblas, Evaluation

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.