Case Report

Case Report

Cognitive Neuroscience Contribution to Police Officer Fitness for Duty Assessment: 2 Case Examples

Stephen E Berger1*, Bina Parekh2, Michael Berger3 and Carolyn Ortega4

1Department of Psychology, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Irvine, USA

2Department of Psychology, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Irvine, USA

3Touro Worldwide University, USA

4California Southern University, USA.

Stephen E Berger, Department of Psychology, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Irvine, USA.

Received Date: February 04, 2020; Published Date: February 18, 2020

Abstract

It is essential that the public has confidence that police officers are Fit for Duty. Of course, that starts with being physically fit to perform the demands of their jobs. However, it is also essential that they are of sound mind also – that they are Fit for Duty. The assessment begins during the initial hiring process. In the United States, each individual state sets the standards that police officers have to meet to be considered Fit for Duty. There will be individual differences among the various police organizations in each state. Thus, not only will state police departments have their standards, counties, cities and other jurisdictions will have their standards. In assessing a police officer’s quality of mind, cognitive neuroscience has much to contribute. This article presents two different police officers who were assessed for Fitness for Duty. One was referred by the officer’s own Department due to questionable actions on the job. The other officer self-referred after suffering a head injury, and after taking actions that the officer thought was inappropriate. Data from the cognitive neuropsychological evaluations of each officer are presented. There is an emphasis on the results from the Rorschach, as the differences between those profiles were remarkably divergent, yet each officer was having problems conforming their behavior to proper standards, but each of them for different reasons. The analyses of their psychological assessments demonstrate how cognitive neuroscience can be applied to assessing police officers’ psychological fitness for duty.

Introduction

It challenges credulity to imagine a civilized society without a police force. It would be lovely if all citizens obeyed laws and did not commit crimes. That state of human development and functioning has clearly not occurred yet. Therefore, society is dependent upon some kind of police force to enforce the laws and provide protection for citizens. Obviously, the police force itself must be law abiding and competent to provide professional, police services. Consequently, police officers must be physically, intellectually, emotionally, and characterologically capable of enforcing and abiding by the laws.

To that end, societies must assess whether officers are capable and competent of performing their job duties. This paper focuses on the intellectual and emotional capabilities of police officers. To help ensure that police officers have the intellectual and emotional capability of performing their jobs, laws are enacted to provide a legal mechanism for assessing the intellectual and emotional capa bility of police officers. The task of assessing Fitness for Duty is a reflection of the concept of whether a given employee is capable, physically, intellectually and emotionally of satisfactorily performing their job. Thus, assessments of applicants for a job as well as reassessments of current employees occur frequently.

Legal Foundations for Police Officer Fitness for Duty Evaluations

The assessment of a police officer’s Fitness for Duty is encoded in American Law. Specifically, a police officer may be discharged for cause [1,2]. For example, cause is defined in the State of Illinois as a “substantial shortcoming recognized by law and public opinion as a good reason for termination,” and a “substantial shortcoming which renders the employee[’]s continuance in office in some way detrimental to the discipline and efficiency of the service” [2,3]. In an illustrative recent (2016) Illinois Appeals Court ruling [4], the Court stated, “There is a well-defined and dominant public policy in Illinois in favor of a disciplined and efficient police force comprised of officers who are fit for duty.” See, e.g., (policy in favor of ensuring public safety and maintaining a reliable, responsible police force) [5].

Since the two case examples provided here occurred in the State of California, some relevant aspects of California law are provided here. Under California Government Code section 12940(f) (2), covered employers may require that an employee undergo a medical or psychological examination or make medical or psychological inquires of employees that are “job related and consistent with business necessity” [6]. Under California Government Code section 12940(f)(2), covered employers may require that an employee undergo a medical or psychological examination or make medical or psychological inquires of employees that are “job related and consistent with business necessity” [7]. In regard to California, California Government Code Section 1031 (8) mandates that all peace officers in California “[b]e found to be free from any physical, emotional or mental condition which might adversely affect the exercise of the powers of a peace officer” [8].

Psychological Assessment of Fitness for Duty

The history of the application of testing instruments being used for selection of employees and personnel can be traced to World War I where the use of the Army Alpha (literate version) and Army Beta (illiterate version), spearheaded by psychologist Robert Yerkes and six others, sought out to systematically classify individuals for roles based on their mental aptitude [9,10]. Given the perceived efficiency that this process provided during World War I for recruits, private industry and organizations began to apply similar models to streamline employee selection based on various criteria unique to their organizations. According to the literature, use of testing measures within organizational structures taps the following areas, or combination of areas: intellectual/aptitude tests, psychomotor abilities, employment specific knowledge (i.e. work sample), vocational inclination, and personality [11].

Similarly, the application of psychological testing with police officers, sets out to establish whether the individual is capable of managing the inherent stressors associated with the role, in addition to the personality and intellectual ability to follow organizational policy [12]. According to Ellen Kirschman, Ph.D., a police psychologist, the following philosophy underlies the psychological testing of police officers and candidates: “1) establishing whether the individual has the minimum threshold for psychological qualification as established by legal statutes and regulations; 2) does not have behavioral health issues that may impede or infringe on their ability to perform the role of a police officer safely; and 3) is able to manage the various stressors associated with the role. Holistically, the psychological evaluation of police officers both as a pre-screening and Fitness for Duty sets out to establish whether the individual is able to behave with integrity, be a team player, understand social situations, and modulate their reactions and emotional states to stress provoking situation” [13].

Clearly, the assessment of the cognitive processes and emotional functioning of police officers is a critical part of any assessment of Fitness for Duty. In addition, such an assessment often includes more than just an assessment of intellectual abilities that may need to include neurocognitive functioning. Two case examples are presented here. In each example, there were reported problems with the functioning of the officers. The psychological assessments resulted in meaningful differences between the officers in their neurocognitive and emotional functioning and the effects on the behavior of each officer. Consequently, these cases provide evidence of the wide range of effects that neurocognitive assessment can demonstrate in understanding the observable behavior of police officers and their Fitness for Duty. To protect confidentiality, gender will not be indicated, and the officers will be referred to simply as: Officer 1 and Officer 2.

Case Examples

Officer 1

This Officer was referred for a Psychological Reevaluation by their Department because of inappropriate, unacceptable behavior during interactions with the public while performing their job duties. There had been previous psychological evaluations by staff personnel. The most significant result was that it had been strongly recommended that the Officer obtain formal psychotherapy. However, the Officer did not obtain such services, and on the job problems continued. Other Officers did not want to interact with this Officer – not on the job and not even away from the job.

Finally, it was determined that a definitive evaluation must be conducted, and that a licensed psychologist rather than an unlicensed, staff psychologist should conduct the evaluation. When the licensed psychologist (the senior author) met with the Officer, the psychologist was asked, “When will someone make a final decision.” The psychologist said, “I will.” The Officer said, “That is all I want to know.” The Officer then proceeded to participate cooperatively in all aspects of the Assessment. In addition to reviewing available records, and conducting a Clinical Interview, the psychologist also administered the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) [14] and the Rorschach Inkblot Technique [15].

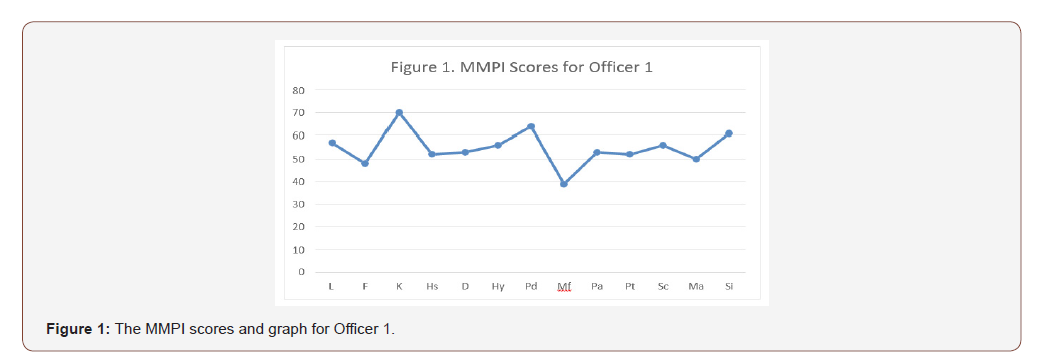

The results from the MMPI are usually presented in the form of a graph. That graph is presented below as Figure 1. A quick glance at the profile gives some clues regarding Officer 1’s psychological functioning. In understanding results of the MMPI, certain basic concepts are needed. The usual graph of the scores on the common scales are presented to the left and are called Validity scales, and to the right are the Clinical scales. The raw scores obtained by the individual are then converted to Standard Scores referred to as T-scores. The average for the standardization sample are represented as a T-score of 50. Low scores are T- scores of 30 and below. High or Clinically Elevated scores are T-scores of 70 or above.

A quick glance at Officer 1’s Clinical scales shows that the Officer does not have any scores that would suggest that he is suffering from a severe mental illness. It is also quickly noted the K Validity scale is right at the T-score of 70. That score suggests that Officer’s self-perception is as a person who does the right thing, conforms to society’s norms as to how a person should think, react, behavior. However, the magnitude of the scale suggests that it is unlikely that the Officer really is such a lovely person. It suggests a person who is defensive about their own faults and is resistant to recognizing those faults and their own contribution to problematic interpersonal situations – which are routine in police work. In addition, the slightly elevated T- score on Si also suggests that interpersonal situations are not the Officer’s forte. Finally, the highest score is on the Pd scale. Thus, one of the most likely troubling issues for this Officer is likely to be when anger is aroused, especially if the Officer is feeling disrespected or challenged, and especially if the situation is one the Officer defines as “family,” such as the psychological equivalent of: I came to be of help – like I am your family and you are disrespecting me by not accepting my authority and, in my mind, resisting me – with the outcome being that the Officer’s anger is aroused and the Officer’s behavior becomes inappropriate.

In the decision of the Illinois Court referenced above, there was a case of a police officer who had been found to be unfit. A portion of the psychological evaluation was referenced in the Court’s decision, and it reads almost like that of Police Officer 1. The decision reads in part: [has] “significant potential to minimize his psychological problems, misinterpret the motives of others, act on these inaccurate beliefs and be self-righteous and punitive … MMPI “profile” is associated with “repressed anger, passive aggressive behavior, and … he can provoke others into reactions that he would take as confirming of his projections …[ MMPI] “profile” is associated with “repressed anger, passive aggressive behavior...”.

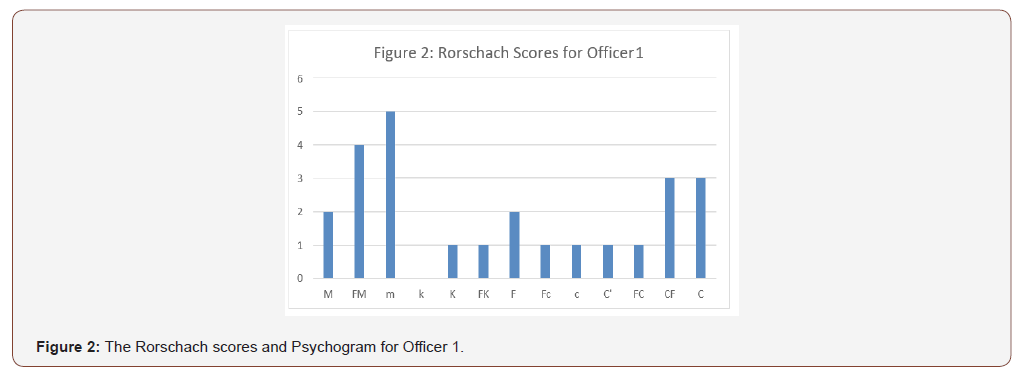

With these questions arising from the self- report, yes/no choices, “objective” MMPI, the Rorschach presents us an opportunity to assess neurocognitive functioning as it affects the officer’s perceptions of ambiguous situations. In this instance, the Rorschach was scored according to the Klopfer system and the resulting Psychogram is presented as Figure 2 [15]. To the seasoned interpreter, several aspects of the Psychogram jump out from the visual presentation, and it is difficult to choose which parts to address first, and which ones next. However, because the basic question here is whether this Officer is Fit for Duty – can be sanctioned to carry a gun, -the interpretation will start with the far-right side of the Psychogram.

What jumps out visually, is all of the color dominated responses (C, CF), which reflect raw emotions with little structure or organization (FC). Just seeing those response categories raises a concern about this person’s ability to control the behavioral expression of their emotions when those are aroused. Consequently, one immediately looks at the category of response that is indicated by the letter F. Given all of the raw emotion that is revealed by the Rorschach, one hopes to find a large number of responses scored in the F category, indicating a substantial ability to respond to ambiguous and possibly emotion arousing situations with calm, structured, well organized, appropriate responses. This Officer has almost no such ability. As a subtle aspect of Rorschach interpretation, it should be noted that the color responses (C, CF) are scored as Additional aspects of the Main responses. This is interpreted as indicating that the emotionality is not the most likely thing one experiences when encountering the Officer, but that under the surface is this great emotional vulnerability – a volcano waiting to explode.

The Main responses that we are most likely to encounter with the Officer is a degree of impulsiveness– a sense of immaturity (FM), although to his credit, he does have 2 responses that provide a very positive interpretation as he had two M (human movement) responses that suggest some ability to empathize with and relate positively to others. Unfortunately, the ability of the Officer to use that ability is compromised by his immaturity/impulsiveness (FM), and an underlying reservoir of tension (m) that is on the surface but lies in abundance under the surface (Additional m responses). It is also apparent that the Officer has an underlying desire for attention/ approval/affection (Additional c (texture) responses) and Hy (T-score = 68) from the MMPI.

When the test results are put together, it can be seen that the Rorschach as a lot to offer in the assessment of a police officer’s Fitness for Duty [16,17]. In regard to Officer 1, we get a picture of an individual who has significant vulnerability to act with inappropriate emotionality, especially in interpersonal situations, not because of a mental illness, but because the Officer has unresolved feelings of anger, hurt, rejection, of not being appreciated for the good person that is the Officer’s self-perception. Thus, when this Officer feels disrespected, the officer is vulnerable to react impulsively (act on his thought without adequately self-assessing, and possibly with intense, uncontrolled emotionality) because underlying tension is aroused unleashing intense, inappropriate and disorganized emotionality. Therefore, the Officer and the Officer’s Department were informed that the Officer could not be approved for carrying a gun (a requisite for Fitness for Duty), and that clearance could not be considered until the Officer had received adequate professional services to help the Officer become aware of, recognize, accept and obtain peace regarding the demons lucking under the surface that endanger the public and the Officer when those demons are aroused. The Officer was relieved of duties and subsequently sought disability retirement.

Officer 2

Officer 2 was a very different individual. The Officer did not have any document problems on the job. However, the Officer felt that they were starting to engage in appropriate actions on the job. The Officer reported to the first author that on one occasion, the Officer had shot the Officer’s gun when there was no legitimate reason to do so, The Officer reported that on another occasion, the Officer had pulled over a teenager, and without justification had thrown the teen onto the hood of the teen’s car. The Officer reported that there had been a discreet incident after which these behaviors had begun to occur. The Officer was insistent that such incidents had never occurred prior to the relevant incident. The Officer stated that during an automobile chase of a person who had committed a very significant crime, the Officer was involved in an auto accident and the Officer’s suffered a significant head injury. While the Officer did not seem to require medical attention at the time, the Officer now noted the above kinds of impulsive behaviors occurring.

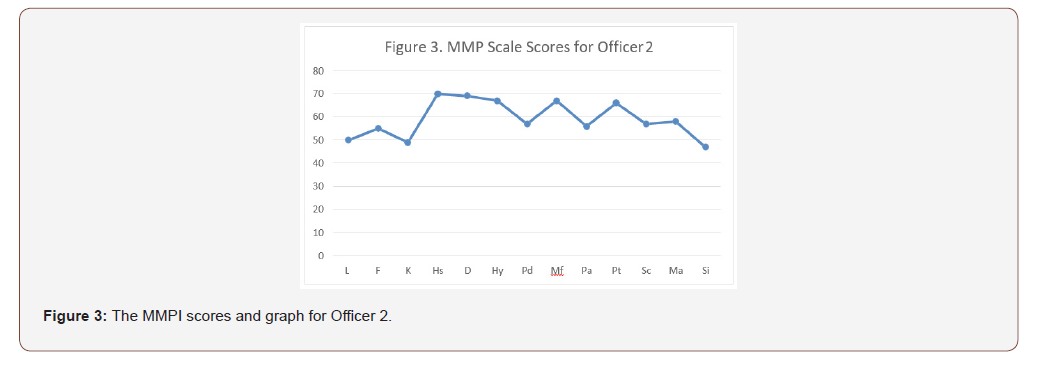

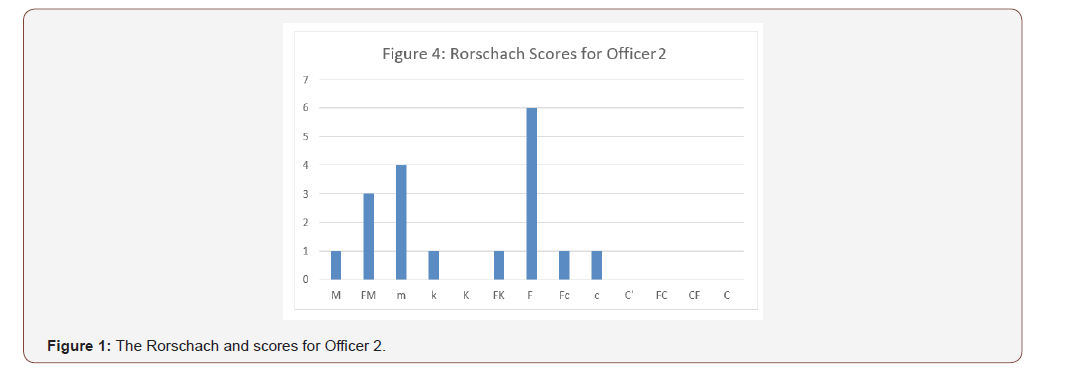

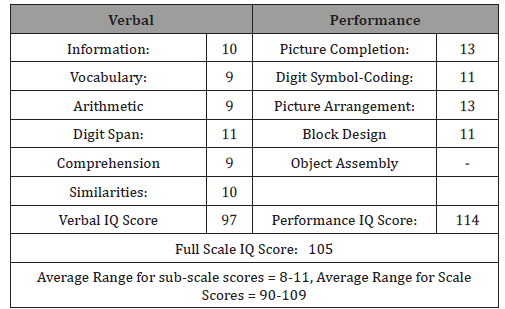

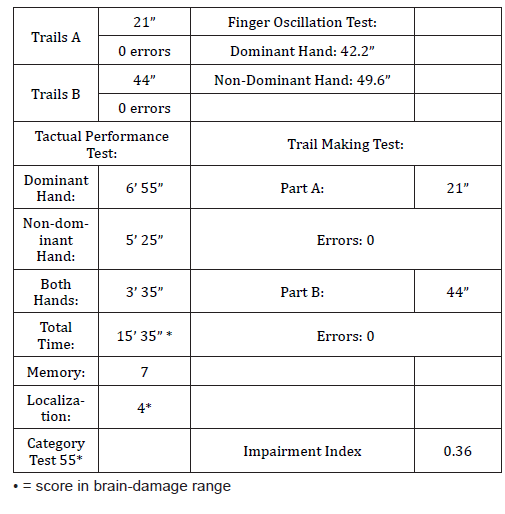

In this instance, it was felt that a full neurocognitive battery was justified. Therefore, in addition to the assessment of emotional functioning (MMPI and Rorschach Inkblot Technique) [14-17], the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Test (WAIS) [18], and the Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery [19] were administered. The results for the WAIS are reported in Table 1, and the results for the Halstead-Reitan are reported in Table 2. The results for the MMPI are found in Figure 3, and the results for the Rorschach are shown in Figure 4.

Table 1:Wechsler adult intelligence scale (WAIS).

Table 2:Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological test Battery.

The Validity scales from the MMPI indicated that Officer 2 was willing to acknowledge faults (K scale= 50), and did not report being in great psychological distress, nor did the officer report experiencing psychotic-like or highly unusual symptoms (F scale = 56). Probably most significant is the fact that the Officer’s highest score was on a scale (Hs = 70) that indicates that a person is basically saying: My body doesn’t work right. When this is the experience of people with a psychotic disorder, then their reports about their body malfunctions are usually quite unusual and unreal symptoms, such as “my stomach is missing.” In this instance, the proper interpretation is the Officer’s sense that something wasn’t right about his body’s (his brain’s) functioning. In addition, there were no suggestions from the MMPI that the officer had difficulties with anger (Pd T-score below 60), nor uncontrolled emotionality (MA T-score = 58). He did have some elevation with a scale that in his situation is interpreted as reflecting significant anxiety about what is happening (PT T-scale = 67). While his scores were not elevated over the cut-off T-scale of 70 for clinical significance (a major indicator of a diagnosable mental illness), his sense that something was not right about his body and his consequent anxiety approached clinically significant levels [20].

An examination of the Officer’s Rorschach Psychogram revealed a clearly significantly different pattern from that of Officer 1. In contrast to Officer 1, Officer 2 did not have any signs of uncontrolled emotionality (no color, C responses). The Officer did exhibit some responses indicating immaturity (FM) and significant tension (m), that would be viewed as under the surface. However, in contrast to Officer 1, Officer 2 demonstrated what should be enough well structured, organized responses (F) that should enable him to contain his immaturity and underlying tension. Thus, the results from the MMPI and Rorschach provided extra relevance and importance of the neuropsychological tests of the Officer’s neurocognitive functioning.

In regard to the WAIS (Table 1), the Officer obtained a Full- Scale score (105), high in the Average range (90-109), almost at the Above Average range. Although there was very little scatter among the Officer’s sub-test scores, it is significant that the officer had no overlap of scores from the Verbal sub-tests and the Performance sub-tests. That fact is also striking since as a college graduate, we would expect that the Verbal sub-tests would be higher than the Performance sub-tests. Certainly, there is differences among individuals, but when people vary from the norm, note must be taken in case this is not normal variation. Since there is a question here whether this Officer has suffered a brain injury that impairs ability to suppress impulses, resulting in the incidents described above, an examination of the Officer’s neurocognitive functioning on the Halstead-Reitan becomes particularly informative. Based on the scores from the WAIS, there is specific suspicion about impaired left, cerebral hemisphere functioning.

The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery scores for Officer 2 are presented in Table 2. As can be seen in Table 2, the Officer obtained an Impairment Index of .36, which suggests that if a brain impairment is present it most likely is either likely to be localized and/or is relatively mild – as if a brain injury is ever mild to the person suffering it. There were several scores that the Officer obtain that fell into the brain damaged range. Despite scoring in the Average range on both Verbal and Performance sub-tests on the WAIS, as well as tests of reasoning ability on both Verbal and Performance measures (Comprehension, Similarities, Block Design), the officer had an impaired score on the Category sub-test of the Halstead-Reitan battery, suggesting impaired reasoning ability, implicating the frontal lobe, The score was only slightly above the brain-damage cut-off score, suggesting a mild degree of impairment, although with his IQ test scores, the individual would not be expected to have impairment on the Category sub-test. That result suggests that the scores observed on the WAIS are lower than what the Officer probably would have been able to attain prior to the head injury

Similarly, the scores obtained on the Finger Oscillation sub-test indicate impaired functioning with the right hand. Here the degree of impairment appears to be more than mild as the Officer would have been expected to obtain a score about 5% greater with the dominant, right hand than with the non-dominant, left hand (expected score of about 51.45, but only obtained 42.2). Since the Officer is right-handed, the scores from the Finger Oscillation test strongly suggest a left, frontal lobe impairment. Thus, there were two results strongly implicating left, frontal lobe impairment.

Finally, what was also noteworthy is that the Total Time to complete the Tactual Performance Test exceeded the allotted Total Time. Although none of the times for Dominant Hand, Non-dominant Hand, nor for Both Hands exceeded time limits, each was slow enough that it pushed the Total Time just over the allotted time. In addition, the Officer’s score for the Localization measure also fell into the brain-damage range. Thus, on two of the three measures of the Halstead-Reitan battery that are considered the most sensitive to brain impairment (Category Test and Localization measure), the Officer’s scores fell into the brain damage range.

Based on the test results obtained here, it appears that Officer 2 has suffered a significant brain injury. The results indicate that a diagnoseable mental illness does not appear to be the problem producing his behavioral difficulties. The best understanding of what has happened to Officer 2 is that despite the fact that the Officer’s characterological and personality functioning is such that the Officer should be able to resist inappropriate impulses that arise, unfortunately, brain functioning is impaired enough to interfere with judgment and the ability to resist impulses – functions usually associated with the frontal lobe. While the degree of impairment might legitimately be classified as mild, that mild degree of impairment causes the Officer to be Unfit for Duty. The Officer decided that it was appropriate to leave the police force and pursue an opportunity in a professional sport where aggressive impulses would be sanctioned.

Conclusion

Police officers put their lives at risk for us every day they are on the job. They need to have the character, physical fitness, intelligence and emotional health to competently protect us. If a police officer has overt prejudice, unconscious bias, character flaws, inadequate reasoning or judgment, is physically impaired, emotionally compromised, then our lives are at risk also. Cognitive neuroscience has resources to help protect the officer and therefore, us.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of Interest.

References

- What is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)? 42 USC. 12112.

- Clark, 245 Ill. App 3d at 393.

- Dowrick V (2005) Village of Downers Grove. 362 Ill. App 3d 512-521.

- Illinois Appeals Court ruling (2016) IL App (2d) 150402-U No. 2-15-0402 Order filed.

- Turner V (1999) Fletcher. 302 Ill. App 3d 1051-1056.

- California Government Code Section 1031(f).

- California Government Code section 12940(f)(2).

- California Government Code Section 1031(8).

- Anastasi A (1982) Psychological Testing. 5th Macmillan. New York, USA.

- Murray DJ (1983) History of Western Psychology. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice Hall, New Jersey, USA.

- Stone CH, FL Ruch (1979) Selection, Interviewing, and Testing. In: ASPA Handbook of Personnel and Industrial Relations. D Yoder, HG Heneman (Eds.). Bureau of National Affairs Washington DC, USA, pp. 4117-4158.

- Wechsler D (1955) Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. The Psychological Corporation, New York, USA.

- Fischler GL (2018) Psychological Fitness-For-Duty Examinations: Practical Considerations for Public Safety Departments Minneapolis, USA.

- Kirschman E (2017) Pre-employment Psychological Screening for Cops. Psychology Today.

- McKinley JC, Hathaway SR (1940) A multiphasic personality schedule (Minnesota): II. A differential study of hypochondriasis. Journal of Psychology, 10,255-268.

- Klopfer B, Davidson HH (1962) The Rorschach Technique: An Introductory Manual. Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc, New York, USA.

- Gormally JF (2008) The Rorschach in fitness for duty evaluations. In: Gacono CB, Evans FB (Eds.) Kaser-Boyd N, Gacono LA (Collaborators), The LEA series in personality and clinical psychology. The handbook of forensic Rorschach assessment. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 301-319

- Pavšič Mrevlje T (2018) Police trauma and Rorschach indicators: An exploratory study. Rorschachiana, 39(1): 1-19.

- Wechsler D (1955) Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. The Psychological Corporation. New York, USA.

- Reitan RM, Davison LA (1974) Clinical Neuropsychology: Current Status and Applications. John Wiley & Sons. New York.

-

Stephen E B, Bina P, Michael B. Cognitive Neuroscience Contribution to Police Officer Fitness for Duty Assessment: 2 Case Examples. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 3(3): 2020. OAJAP.MS.ID.000564.

Cognitive, Neuroscience, Fitness, Neuropsychological, Psychological assessments, Intellectually, Emotionally, Characterologically, Psychological examination, Psychological inquires, Psychological evaluation

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.