Review Article

Review Article

Cell Phone Addiction in Adolescents: A Narrative Review

Tiffany Field*

University of Miami/Miller School of Medicine, Fielding Graduate University, USA

Tiffany Field, University of Miami/Miller School of Medicine, Fielding Graduate University, USA.

Received Date: March 06, 2020; Published Date: March 31, 2020

Abstract

This narrative review on cell phone (smart phone) addiction in adolescents is based on papers published during the years 2014-2020 that appeared on PubMed and PsycINFO. The prevalence of cell phone addiction has varied widely across countries as have the scales for that addiction. Cell phone addiction effects include psychological problems (loneliness, depression, social anxiety), physical problems (sleep disturbance, hypertension) and problematic behaviors (sexting, substance use). Risk factors/predictors include parental cell phone addiction, Internet addiction, gaming, and fear of missing out. Methodological limitations include the lack of a standard cell phone addiction classification and the reliance on self-report questionnaires that often do not include time spent on cell phones and the nature of cell phone use (texting, scrolling, chatting) as well as potential underlying mechanisms such as social anxiety. Further, most of the studies are cross-sectional, not longitudinal, so that the direction of effects cannot be determined. Researchers, nonetheless, have arbitrarily assigned behaviors as outcome or predictor variables when they may be more validly considered comorbid activities.

Introduction

Cell phone addiction in adolescents: a narrative review

For this narrative review, a literature search was conducted on PubMed and PsycINFO for the years 2014-2020. Exclusion criteria included non-English papers, case studies, under-powered samples and non-juried papers. Following exclusion criteria, 61 papers were included. Although most of the adolescent cell phone addiction papers during these years have focused on negative effects of and risk factors for excessive use by adolescents, this review also includes brief summaries on the prevalence noted in different countries and the different scales that have been developed for assessing cell phone addiction. Only one intervention study was found. This review is accordingly divided into sections on prevalence, effects, risk factors/predictors and an intervention for cell phone addiction.

Prevalence of cell phone addiction

The papers reviewed here, approximately a third used the term smartphone addiction another third referred to it as mobile phone addiction and the most recent papers labeled it cell phone addiction. This variety of terms reflects the diversity of studies across multiple countries, the relative lack of consensus about how to define cell phone addiction and the use of six different scales that have been developed or adapted as abbreviated scales or as culturally relevant measures. The Oxford English dictionary definition of addiction is a “condition of being addicted to a particular substance, thing or activity”. Medically it is a “chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive seeking, continued use despite harmful consequences and long-lasting changes in the brain”.

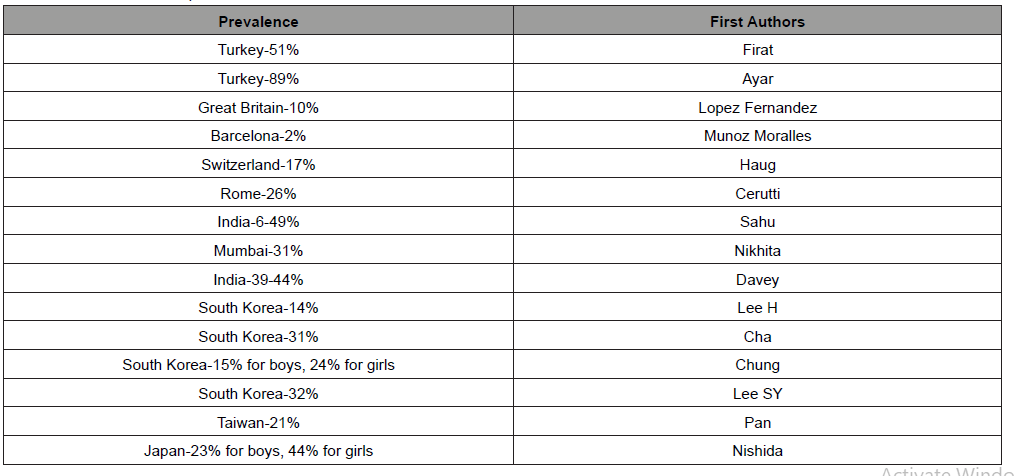

Like internet addiction, the prevalence of cell phone addiction has widely varied (2-89%) depending on the scale used and the location of the research (Table 1). And, in some countries, smart phones are continuously connected to the internet (for example, 89% time in a sample of Turkish tenth grade students) (N=609) [1]. Moving from west to east in Europe and then Asian countries, the prevalence rates, the effects and the risk factors have significantly varied. The U.S. is not included in this review of prevalence data inasmuch as no U.S. cell phone addiction prevalence papers appeared in this recent literature. In a study using the Mobile Phone Problem Use Scale, British secondary school students (N=1026) completed questionnaires, and the prevalence of mobile phone addiction was said to be 10% [2].

Table 1:Prevalence of cell phone addiction in adolescents and first authors.

The problem was greater among adolescents between 11 and 14 years of age and the risk factors were: studied in a public school, considering oneself to be an expert user of technology, and students who attributed the same use to their peers. For Hispanic cultures, the prevalence varied by study. For example, in Barcelona, problematic use of mobile phones was only 2% (and gaming was 6% and Internet problematic use was 14%) [3]. In this sample, problematic mobile phone use was associated with substance use. In a sample of several different Spanish-speaking countries, 50% of the adolescents (N=1276) presented problems with the Internet, mobile phones, video games, instant messaging and social networks [4].

Moving over to Switzerland, in a convenience sample of students from Swiss vocational school classes (N=1519), 17% of the students presented smartphone addiction [5]. In this sample, smartphone addiction was associated with the following risk factors: longer duration of smartphone use on a typical day, a shorter time until first smart phone use occurred during morning hours and reporting that social networking was the most personally relevant smart phone function. Students who engaged in less physical activity and reported greater stress also experienced problematic smart phone use.

Two different groups have studied mobile phone addiction or problematic cell phone use in Italy. One group reported that problematic cell phone use for text messaging increased from 14% in sixth grade to 16% in seventh grade and 20% in eighth grade [6]. A logistic regression suggested that being drunk at least once and excessive energy drink consumption increased the odds of problematic use. Lower odds of problematic use were associated with reading, better academic performance and longer hours of sleep. In a study from Rome, 26% of the Italian students (N=1004) were abusers of mobile phones, while the prevalence of Internet abuse was approximately 15%, and 20% were abusers of both the internet and mobile phones [7].

Three different studies from Turkey appeared in the recent literature on adolescent problematic smartphone use. In one study, problematic smartphone use was detected in 51% of the adolescents (N=150) [8]. In this study, the factors that most predicted problematic smartphone use were somatization, interpersonal sensitivity and hostility. In another Turkish sample 89% of the students (N=609) were connected to the Internet continuously with their smart phones [1]. Male adolescents with high levels of Internet addiction also had high levels of smartphone addiction. In a study that addressed nomophobia (fear of losing one’s cell phone), the data showed that 9% of Turkish adolescents were severely nomophobic, 72% were moderately nomophobic and 20% were mildly nomophobic [9].

In India, the prevalence of mobile phone addiction ranged from 6-49%. The lowest prevalence (6%) was reported in a systematic review [10]. In this review, problematic phone use was associated with feeling insecure, staying up late at night, impaired parentchild relationships, impaired school relationships, compulsive buying, pathological gambling, low mood, tension and anxiety, leisure boredom, hyperactivity, conduct problems and emotional symptoms. This prevalence rate may have been lower than most because of the inclusion of children in the sample.

In a sample of Mumbai adolescents, cell phone dependence was found in as many as 31% of eighth, ninth and 10th grade students (N=415) [11]. In this study, dependence was associated with male gender, type of mobile phone used, average time per day spent on the phone and years of mobile phone usage. An even higher range was reported in a systematic review and meta-analysis on Indian adolescents (39-44% in a sample of 1304) [12]. This meta-analysis suggested that smartphone addiction could lead to dysfunctional interpersonal skills and negative health risks. In a study by the same group of investigators on the phubbing phenomenon (snubbing someone in favor of a mobile phone) in a sample of adolescents from India (N=400), the prevalence was 49% [13]. The predictors of phubbing were Internet addiction, smartphone addiction, fear of missing out and the lack of self-control. The effects of phubbing included depression and distress as well as relationship problems.

South Korea has also been the source of several studies on cell phone use in adolescents. In one study on middle school students (N=370), the prevalence of smartphone addiction was 14% [14]. The addiction group as compared to the non-addiction group had higher scores on “online chat”. They also had higher scores on habitual use, pleasure, communication, games, stress relief, and not being left out. In a regression analysis, the significant risk factors were female gender, preoccupation and conflict. Further, the addiction group had higher scores on parental punishment. This study was unique in elaborating not only the prevalence but the types of use and parental attitudes regarding the adolescents’ smartphone use.

In a larger sample of middle school students in South Korea (N=1261), a greater prevalence was noted for smartphone addiction (31%), likely because an at-risk group was included in the sample [15]. Here, too, they elaborated on the type of use, indicating that mobile messaging was the most prevalent followed by Internet surfing, gaming and social networking. The risk factors for smartphone addiction were daily smart phone use, social networking, duration of use and overuse of gaming.

In an even larger sample of South Korean adolescents (N=1796), the prevalence of at-risk users was 15% for boys and 24% for girls [16]. Those who were at greater risk for smart phone addiction were female, consumed alcohol, had lower academic performance, did not feel refreshed in the morning and initiated sleep after 12 AM.

In still another study from South Korea, middle school students (N=555) were divided into four categories including Internet plus smartphone problem users (50%), problematic Internet users (8%), problematic smartphone users (32%) and healthy users (11%) [17]. The dual-problem users (Internet and smartphone) scored highest on the Addictive Behavior Scale. Problematic Internet use was more prevalent in males and problematic smart phone use was more prevalent in females. In a large sample study (N=10,775) from Taiwan, the focus was specifically on mobile gaming addiction [18]. Problematic mobile gaming was 21% among junior high school students and 19% among senior high school students. The Problematic Mobile Gaming Questionnaire revealed three factors of addiction including compulsion, tolerance and withdrawal.

Gender differences have also been noted on the prevalence of cell phone addiction in adolescents [19]. In a study from Taiwan, adolescent females showed a greater degree of smartphone dependence than adolescent males [20]. This gender difference in prevalence may relate to the negative correlations noted between smartphone dependence and vitality/mental health specifically in males which may have discouraged cell phone dependence in males. In a study from Japan on a sample of high school students (N=195), female adolescents spent more hours a day on smart phones than males [21]. Forty four percent of females and 23% of males spent three hours a day on smart phones. Gender differences also emerged on the type of smartphone use. Females spent longer hours on Internet browsing, on social networking sites and on online chat. Online chat, in turn, was associated with depression. Males spent more time playing games, but their smart phone use was not correlated with depression, a finding that is inconsistent with the inverse relationship between cell phone dependence and mental health just noted in Taiwanese male adolescents.

It is unclear why the prevalence of cell phone addiction has varied so widely (2-89%) across countries and even within countries given that no cross-cultural comparisons have appeared within studies in this literature. The sources of prevalence data have varied on so many other factors that could affect the prevalence rates such as urban versus rural location, survey versus school sampling, younger versus older adolescents, gender distribution of the samples, and type of cell phone addiction scale used.

Scales for cell phone addiction

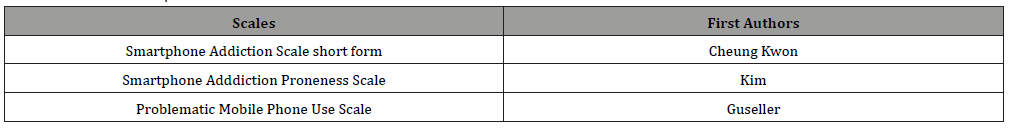

Table 2:Scales for cell phone addiction and first authors.

Several scales have been developed to assess cell phone addiction in adolescents. These include the Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Form, the Smart Phone Addiction Proneness Scale, the Mobile Phone Problem Use Scale, the Problematic Mobile Phone Use Scale and the Nomophobia Questionnaire (Table 2).

In a sample of Hong Kong children and adolescents (N=1901), factor analysis was conducted on the Smart Phone Addiction Scale- Short Form [22]. The convergent validity of the scale was also assessed using sleep, social support and depression scales. These analyses revealed a three-factor model including dependency, the incidence of a problem, and time spent on the cell phone. The scores on the short version scale were positively correlated with the sleep and depression scales and negatively correlated with the social support scale. A linear regression suggested that female adolescents who had highly educated caregivers and spent more time on cell phones during the holidays showed greater vulnerability to becoming addicted. In another study on the Smart Phone Addiction-Short Form, South Korean adolescents (N=540) completed the scale [23]. In this case, the internal consistency and concurrent validity of this 10-item scale were verified with a Cronbach’s alpha of 91.

In another study on South Korean students (N=795), the Smartphone Addiction Proneness Scale was developed [24]. This 15-item scale was comprised of four subscales including disturbance of adaptive functions, virtual life orientation, withdrawal and tolerance. This scale also had good psychometric properties. Still another scale was shortened from 27 to 10 items following a survey of Swiss students(N=412) [25]. A principal components analysis revealed five factors related to addiction symptoms including loss of control, withdrawal, negative life consequences, craving and peer dependence. In a study on Turkish high school students (N=950), the psychometric properties of the Problematic Mobile Phone Use Scale were assessed [26]. In this case, a factor analysis revealed three factors: interference with negative affect, compulsion/ persistence and withdrawal/tolerance. The scores for the scale were correlated with depression and loneliness scale scores.

A scale has also been developed for nomophobia (“no mobile phone phobia”) to assess the fear of being without a mobile phone [27]. In this study, the 20-item scale was completed by 3216 Iranian adolescents and the psychometric properties were confirmed. The reliability of adolescent’s ratings on the self-report scales, however, has been called into question by at least one study that assessed both parents’ and adolescents’ ratings on the Smartphone Addiction Scale [28]. The results of this study suggested that the prevalence of smart phone addiction was greater based on the parents versus the adolescent’s ratings. And the parents’ ratings were correlated with the average minutes of weekday/holiday smartphone use. The authors suggested that clinicians might want to consider both adolescents and parents smartphone addiction scores for underestimation or over-estimation.

These scales are also highly variable in several ways. The same original scale has been abbreviated or adapted in different ways by researchers from different countries. The scales vary on the number of items, the factors resulting from factor analyses or at least the terms applied to the factors and the variables that are related to their scores. Tolerance and withdrawal are the only factors that are common to a few of the scales. And peer dependence only appears on one of the scales. Some scales also seem to be tapping proneness to addiction and others are measuring addiction. By their titles they reflect different degrees of cell phone use including proneness, problematic use and addiction. And, correlation analyses suggest that they are related to different negative effects. For example, in one study, the scale score was related to loneliness and depression and in another study, the scale sore was associated with sleep problems and depression. It is not surprising, then, that loneliness, depression and sleep disturbances are among those most frequently studied effects of cell phone addiction.

Effects of cell phone addiction

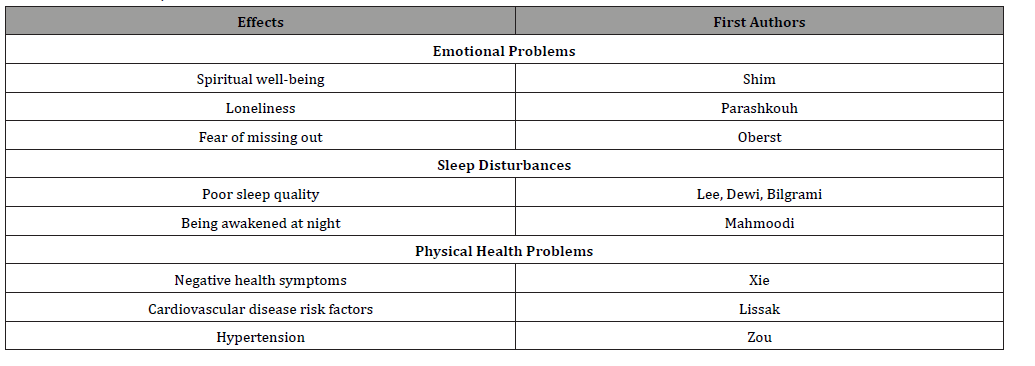

As in internet addiction, cell phone addiction has been associated with several negative effects. These include loneliness, sleep disturbances, anxiety, depression and problematic behaviors including sexting and suicide [29,30] (Table 3).

Table 3:Effects of cell phone addiction and first authors.

Emotional problems: Spiritual well-being has been assessed in a group of adolescents who were high risk for smartphone addiction as compared to those who were not [31]. Although the findings suggested that the high-risk group had lower levels of spiritual well-being, the sample sizes of the groups were significantly different, raising question about the statistical power of this data analysis. The uniqueness of a study on spiritual wellbeing in this cell phone addiction literature is noteworthy

Loneliness has also been assessed as an effect of mobile phone addiction, although it could also be considered a risk factor given that it was studied in a cross-sectional sample, making directionality impossible to determine [32]. In this study, the Cell Phone Overuse Scale was administered along with the Los Angeles Loneliness Scale to Iranian adolescents (N=554). The results of the study suggested that 78% of the adolescents were at risk for addiction to mobile phones and 17% of them were addicted to their use. In addition, a significant relationship was noted between addiction to mobile phones and loneliness. Lower self-esteem, more depressive symptoms and greater interpersonal anxiety were related to excessive cell phone use in a South Korean sample (N=595) [33]. Fear of missing out (FOMO) as well as social networking intensity were also noted to lead to psychopathology including depression and anxiety in a sample of Spanish-speaking adolescents (N=1468) [34].

Sleep disturbances: Several studies have implicated sleep problems resulting from mobile phone addiction. In a study on South Korean adolescents (N=1125), cell phone addiction increased the risk of poor sleep quality but not short sleep duration [35]. In a sample of high school students from Iran (N=1034), frequency of daily messages and being awakened at night for mobile phone use were significantly associated with poor mental health, and poor mental health was noted in 63% of the students [36]. In a study on Indonesian students (N=1074), smart phone use at night was entered as an independent variable and sleep disturbance and depressive symptoms as the dependent variables [37]. Positive relationships were noted between smart phone use at night and sleep disturbances as well as depressive symptoms.

Sleep disturbances, in turn, have been associated with problematic behaviors. In a systematic review of 94 publications since 2006, cell phones were the most popular New Age technology and excessive use was noted to have several negative effects including sleep quality, body composition, mental well-being and problematic behaviors including sexting and pornography [38].

Physical health problems: The excessive use of smart phones has also lead to health problems. In a cross-sectional survey of middle and high school students (N=686), structural equation modeling suggested that sleep quality mediated the relationship between problematic smartphone use and negative health symptoms [39]. In a literature review, excessive cell phone use was associated with sleep disturbances and other risk factors for cardiovascular disease [40]. These included high blood pressure, obesity, low HDL cholesterol, poor stress regulation (i.e. high sympathetic arousal and cortisol dysregulation) and insulin resistance. Other physical health effects included impaired vision and reduced bone density. Psychological effects included internalizing and externalizing behavior, depressed and suicidal behavior. Further support for smartphone addiction being a risk factor for hypertension comes from a study on Chinese Junior high school students (N=2639) [41]. The prevalence of smartphone addiction in that sample was 23% and the prevalence of hypertension was 16%. Obesity, poor sleep quality, and smartphone addiction were significantly and independently associated with hypertension.

As already mentioned, many of the variables that have been labeled effects were arbitrarily entered as outcome variables in regression analyses rather than entered as predictors/risk factors. And, in some cases in this literature, variables have been considered both effects and risk factors. For example, depression has been treated as both an outcome of cell phone addiction and as a risk factor/predictor variable for cell phone addiction. Given that the effects were explored in cross-sectional studies, directionality cannot be determined. Directionality could only be determined in the longitudinal studies. That the effects were derived from correlation studies in most cases suggests that they might more validly be labeled comorbidities or correlates instead of effects. And, surprisingly, although a number of studies were multi-variable, multiple addictions that are thought to be comorbid with cell phone addiction, e.g. sexting, cyberbullying and internet addiction, were typically not assessed within the same studies [42].

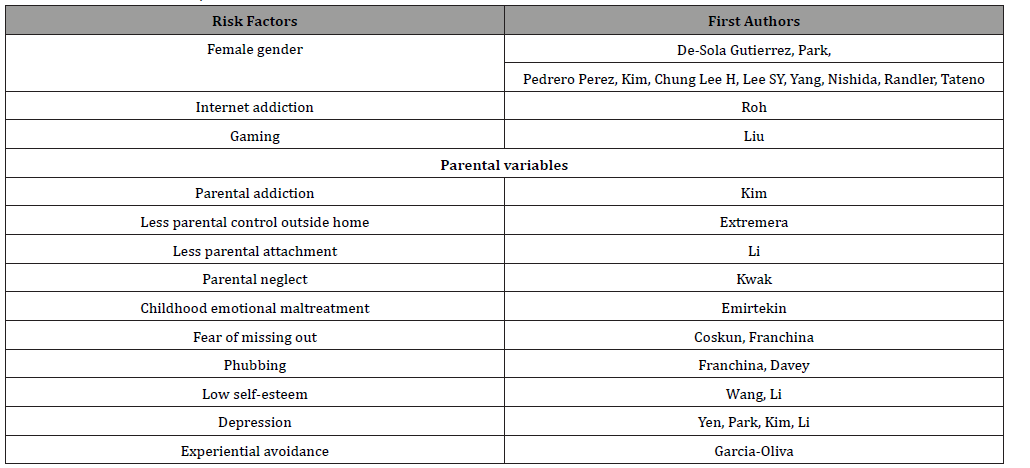

Risk factors/predictors of cell phone addiction

Cell phone addiction is significantly related to internet addiction, although it has a distinct user profile. For example, it occurs more frequently in females [30] and especially those with low self-esteem [43]. Other risk factors include gaming, fear of missing out (FOMO), depression and parental addiction and lack of parental monitoring (Table 4).

Female gender: In several studies already reviewed, the prevalence of cell phone addiction was greater in female than male adolescents. This was noted in Asian countries including Korea, Taiwan and Japan. In two studies on German adolescents reported in the same paper, female gender was a significant predictor of smart phone addiction [44]. In the first of these two studies, the Smartphone Addiction Proneness scale was given to younger adolescents (N=342) and in study two the Smartphone Addiction Scale was given to older adolescents (N=208). Both samples were given sleep measures. The two significant predictors of smartphone addiction were female gender and evening types. Surprisingly, sleep duration on weekends and the midpoint of sleep on weekdays and weekends did not predict smart phone addiction on either scale.

Table 4:Risk factors for cell phone addiction and first authors.

Internet addiction and gaming: The frequent use of the internet and gaming have been significant predictor variables of cell phone addiction in adolescents. In a study from Japan, females used the smart phone primarily for social networking and males favored gaming via the Internet [45]. In this study, the Smartphone Addiction Scale scores were higher in females. And, those with higher scores on the Smartphone Addiction Scale also showed a greater risk for the hikikomori trait (severe social withdrawal). In another study on Korean children and adolescents, multiple regression analyses revealed that scores on the Internet Addiction Test were predictive of smartphone addiction [46,47]. And, smart phone gaming was a significant predictor variable for smart phone addiction in a study from Taiwan [48]. This result was not surprising given that the majority of the adolescents in the sample were males.

2.5.3. Parental variables: Parental variables have been significant risk factors including parental addiction, control, neglect and maltreatment. In a South Korean national survey that included family environment, self-control and friendship quality as predictors of smartphone addiction in adolescents, parental addiction was a significant variable after controlling for the other variables [49]. This was particularly true for adolescents with lower levels of self-control and friendship quality.

In a study on adolescents in Spain (N=845), 42% were considered problematic smartphone users [50]. That group as compared to non-problematic smartphone users differed on gender (females engaging in greater use) and parental control outside the home (less control). The problematic users also had higher scores on a questionnaire that tapped cognitive emotion regulation strategies including having higher self-blame, rumination and catastrophizing.

In a study on adolescents from middle schools in rural China, parental attachment negatively predicted mobile phone addiction [51]. This effect was partially mediated by depression. In a survey of students from middle schools in four regions of South Korea (N=1170), parental neglect was a significant predictor of smartphone addiction [52]. In this multiple mediator model, parental neglect was not associated with problematic peer relations and, surprisingly, problematic relations with peers negatively influenced smartphone addiction. Further, relationship problems with teachers partially mediated the relationship between parental neglect and smartphone addiction. The authors argued that programs were needed to improve relationships with parents and teachers. This was a unique study for its assessment of adolescent’s relationships with peers, parents and teachers and for its very complex findings.

In another multiple mediation model, childhood emotional maltreatment was directly and indirectly associated with problematic smart phone use [53]. The significant mediators were body image dissatisfaction, depression, body image dissatisfactionrelated depression and body image dissatisfaction-related social anxiety. This study on Turkish adolescents (N=443) is unique in its assessment of body image dissatisfaction and social anxiety as potential mediators of problematic smartphone use. The body image dissatisfaction would seem like a pet variable as it has not appeared anywhere else in this literature. And, although social anxiety would appear to be a key reason for social networking on a cell phone, this variable has rarely appeared in this literature.

Fear of missing out (FOMO) and phubbing: Fear of missing out (FOMO) has been defined as anxiety about missing rewarding experiences [54]. And, it is considered a motive for staying aware of what others are doing on social media. It is such a frequent phenomenon that a scale has been created for its assessment. In a study on Turkish adolescents, a significant relationship was noted between scores on scales for FOMO and problematic mobile phone use [55]. A regression analysis suggested that FOMO predicted as much as 28% of the variance in scores on the Problematic Mobile Phone Use Scale. In a study on Belgian adolescents (N=2663), fear of missing out was a significant predictor of excessive use of social media platforms that are private, e.g. Facebook and Snapchat, and it also predicted phubbing behavior both directly and indirectly by its relationship with problematic smartphone use.

The phubbing phenomenon refers to the habit of snubbing someone while using a smartphone. In a study on 400 adolescents in India, the prevalence of phubbing was as high as 49%. The significant predictors associated with phubbing were Internet addiction, smart phone addiction, fear of missing out and the lack of self-control. Phubbing was also noted to have negative effects on social health and relationship health and was related to depression and stress.

2.5.5. Self-esteem: Self-esteem has been a risk factor or a mediator in a couple studies. In a sample of Chinese adolescents (N=768), mediation analysis suggested that self-esteem partially mediated a link between student-student relationships and smartphone addiction [56]. The mediated path was weaker for adolescents with less need to belong. The authors suggested that self-esteem could be a protective factor against smart phone addiction, especially for adolescents who have a strong need to belong.

In another study on a group of Chinese middle school students (N=637), self-esteem was negatively associated with problematic smartphone use [57]. In this study, low self-esteem was a risk factor for problematic smartphone use, but depression mediated the relationship between low self-esteem and problematic smartphone use. Notably, self-esteem was a significant factor in both studies, but the two different research groups chose to treat them as different types of variables, with one group treating self-esteem as a mediating variable and the other group entering it as a risk factor. This is an arbitrary decision given that directionality could not be determined in these cross-sectional studies.

2.5.6. Depression: Depression has been considered a risk factor for cell phone addiction in a few studies. In one study on Taiwanese adolescents (N=10,191), those who had significant depression were more likely to have four or more symptoms of problematic cell phone use including making more cell phone calls, sending more text messages and spending more time on cell phones [58].

In a rare longitudinal study, depressive symptoms were predictive of mobile phone addiction in South Korean adolescents (N=1794) [59]. In this study, depression could be considered a valid predictor as it was assessed at an earlier period than mobile phone addiction. However, both depression and mobile phone use should have been measured at both baseline and follow-up assessments to definitively show depression was a predictor of mobile phone addiction rather than the reverse. In this sample, as in many other samples in this literature, the female adolescents used their mobile phones more often and were at greater risk for both mobile phone addiction and depressive symptoms.

In still another study on South Korean students (N=4512), 8% were considered addicted to smartphone use [60]. In this case, both depression and anxiety were significant predictors of smartphone addiction. In addition, female gender, smoking and alcohol use were significant risk factors. In a sample of Chinese adolescents (N=2016), both social support and positive emotions were buffers for depression in students suffering from mobile phone addiction [57]. In their mediation data analysis, positive emotions had a mediating effect on the relationship between social support and depression.

Experiential avoidance may be an escape from depression. In a study on adolescent technological addictions, experiential avoidance was referred to as a self-regulatory strategy to control or escape from negative thoughts or feelings of distress [61]. Linear regressions suggested that experiential avoidance explained significant variance in the addictive use of mobile phones. In this sense, the “withdrawal” factors on each of the cell phone addiction scales and the “interference with negative affect” on the Problematic Mobile Phone Use Scale may be in part capturing the experiential avoidance phenomenon.

Unfortunately, both the studies on effects and the research on predictors of cell phone addiction have relied on self-report on the addiction scales. As was noted, parental scores on the addiction scale have suggested greater addiction than the adolescents’ selfreports, raising questions about the reliability of adolescent selfreport. Unlike the literature on other adolescent addictions, e.g. the Internet addiction and the gaming research, the cell phone literature is lacking empirical studies that include observations of that behavior that could support the self-report findings.

Except for the reports of gender differences on cell phone use suggesting that female adolescents use cell phones more often for social networking and males for gaming, it’s not clear which types of cell phone use are more addictive or more predictive of cell phone addiction including texting, gaming, Facebook, chat rooms, internet surfing etc. Also, unlike the other research on other adolescent addictions, this literature lacks physiological data such as heart rate variability and fMRI scans as well as biochemical measures including stress hormones and immune data to support the selfreports on physical health problems.

Depression has been frequently entered as a presumed predictor of cell phone addiction in regression analyses. However, Depression as a predictor was only validly assessed in one longitudinal study and even that study has questionable validity inasmuch as depression was only assessed at the baseline period and cell phone addiction at the follow-up rather than assessing both variables at both periods. The other seemingly important predictors appeared in only a couple studies. For example, FOMO was treated as a risk factor in two studies, the need to belong in one study, and social anxiety in one study.

Strikingly few studies assessed relationships with peers, parents or teachers as risk factors. Although parental addiction, neglect and maltreatment appeared in this literature as risk factors for cell phone addiction, relationships with parents were not assessed either by self-report or by observation. Relationships would presumably be negatively affected by cell phone addiction just as they have been by Facebook addiction [62]. Relationships are difficult to study anonymously, but at the very least, relationship questionnaires could be included in the anonymous surveys.

Intervention

Only one intervention study could be found in this literature on smartphone addiction in adolescents. In that study from South Korea, 14% of the sample (N=335 middle school students) had smartphone addiction [63]. Those adolescents engaged in a homebased daily journaling of smartphone use for two weeks. By the end of the intervention period, the adolescents had lower smart phone addiction scores and there was an increase in the scores on parents’ concerns about their adolescents’ smart phone activities.

Surprisingly, unlike the recent research on other adolescent addictions which includes several intervention studies, the cell phone addiction literature was limited to this one intervention study. The effectiveness of the journaling smartphone use intervention for both reducing adolescents’ cell phone use and increasing parental monitoring highlights the importance of intervention research. Self-use of cell phones could be routinely monitored given that many cell phones now graph daily use automatically. The only other research on buffers for cell phone addiction suggested that positive emotions, social support and self-esteem may be effective buffers.

Limitations and Future Directions

Cell phone addiction has varied widely across countries (2- 89%) and even within countries, but no cross-cultural comparisons have been conducted in this literature to address this phenomenon. Many confounding variables could affect the prevalence rates including the location of the study (urban versus rural), the type of sampling (survey versus school sampling), age of sample (younger versus older adolescents), gender distribution of the samples (some samples being only one gender), the specific cell phone addiction scale used and the different ways the different scales have been adapted in the different countries.

The cell phone addiction scales are highly variable including the number of items, the factors resulting from factor analyses, the terms applied to the factors and the effects and predictors that relate to the scores on the scales. The only factors that are common to the scales are withdrawal and tolerance. And peer dependence that is seemingly an important variable, only appears on one of the scales. The scales also differ on the dimension of tapping proneness to addiction or addiction. The titles of the different scales suggest different degrees of cell phone use including proneness, problematic use and addiction. And, correlation analyses suggest that they are related to different negative effects and predictors. For example, in one study, the cell phone addiction score was related to loneliness and depression and in another study, cell phone addiction was related to sleep problems and depression. Those results relate to one research group focusing on loneliness and the other on sleep problems. And, loneliness, depression and sleep disturbances are among the most frequently studied negative effects of cell phone addiction.

As already mentioned, many of the variables were arbitrarily entered as outcome variables in regression analyses rather than entered as predictors/risk factors. And, in this literature, some variables have been considered both effects and risk factors. For example, depression was entered as an outcome of cell phone addiction in some studies and as a risk factor/predictor variable for cell phone addiction in other studies. Directionality/causality cannot be determined in these cross-sectional studies, highlighting the need for longitudinal studies. Many variables may be considered correlates or comorbidities instead of effects or predictors given that they have derived from correlation analyses.

Another surprising aspect of this recent research is that although a number of studies were multi-variable, multiple addictions that are thought to be comorbid with cell phone addiction were not assessed within the same studies., e.g. sexting, cyberbullying and internet addiction. Another methodological limitation is that both the studies on effects and the research on predictors of cell phone addiction have relied on self-report. As was already noted, parental scores on these scales revealed greater addiction than that reported by the adolescents, raising the question of the reliability of adolescent self-report. The cell phone addiction literature is needing empirical studies that include observations of that behavior.

It is also not clear which types of cell phone use are more addictive or more predictive of cell phone addiction including texting, gaming, Facebook, chat rooms, internet surfing, etc. The only exception is the report on gender differences on cell phone use suggesting that female adolescents use cell phones more often for social networking and males for gaming. Unlike the research on other types of adolescent addiction, the cell phone addiction literature lacks physiological data like heart rate variability and fMRI scans and biochemical measures including stress hormones and immune data.

Depression was clearly a valid predictor for cell phone addiction in one longitudinal study, but the results are tenuous given that depression was only assessed at the baseline period and cell phone addiction at the follow-up period rather than both variables being assessed at both periods. The other seemingly important predictors appeared in only a couple studies. For example, FOMO was treated as a risk factor in two studies, the need to belong in one study, and social anxiety in one study.

Unfortunately, very few studies assessed relationships with peers, parents or teachers as risk factors. Parental addiction, neglect and maltreatment were assessed in this literature as risk factors for cell phone addiction, but relationships with parents were not assessed either via surveys or observation methods. Negative relationships with peers, parents and teachers would seemingly be important predictors of cell phone addiction.

Intervention studies are missing from the cell phone addiction literature. Only one intervention study highlighted the effectiveness of journaling smartphone use both for reducing adolescents’ cell phone use and increasing parental monitoring. Many cell phones now graph daily use so that self-use could be easily monitored routinely. Positive emotions, social support and self-esteem may be effective buffers that could be further studied.

Despite these multiple methodological limitations of the recent literature on cell phone addiction in adolescents, the research has highlighted the prevalence, the negative effects and the predictors/ risk factors for the problem. Further research is needed to identify risk profiles for cell phone addiction to help inform prevention and intervention efforts.

Acknowledgement

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of Interest.

References

- Ayar D, Bektas M, Bektas I, Akdeniz Kudubes A, Selekoglu Ok Y, et al. (2017) The effect of adolescents’ internet addiction on smartphone addiction. J Addict Nurs 28(4): 210-214.

- Lopez Fernandez O, Honrubia Serrano L, Freixa Blanxart M, Gibson W (2014) Prevalence of problematic mobile phone use in British adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 17(2): 91-98.

- Munoz Miralles R, Ortega Gonzalez R, Lopez Moron MR, Batalla Martinez C, Manresa JM, et al. (2016) The problematic use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in adolescents by the cross sectional JOITIC study. BMC Pediatr 16(1): 140.

- Pedrero Perez EJ, Ruiz Sanchez de Leon JM, Rojo Mota G, Llanero Luque M, Pedrero Aguilar J, et al. (2018) Information and Communications Technologies (ICT): Problematic use of internet, video games, mobile phones, instant messaging and social networks using MULTICAGE_TIC. Adicciones 30(1): 19-32.

- Haug S, Castro RP, Kwon M, Filler A, Kowatsch T, et al. (2015) Smartphone use and smartphone addiction among young people in Switzerland. J Behav Addict 4(4): 299-307.

- Gallimberti L, Buja A, Chindamo S, Terraneo A, Marini E, et al. (2016) Problematic cell phone use for text messaging and substance abuse in early adolescence (11- to 13-year-olds). Eur J Pediatr 175(3): 355-364.

- Cerutti R, Presaghi F, Spensieri V, Valastro C, Guidetti V (2016) The potential impact of internet and mobile use on headache and other somatic symptoms in adolescence. A population-based cross-sectional study. Headache 56(7): 1161-1170.

- Firat S, Gul H, Sertcelik M, Gul A, Gurel Y, et al. (2018) The relationship between problematic smartphone use and psychiatric symptoms among adolescents who applied to psychiatry clinics. Psychiatry Res 270: 97-103.

- Gurbuz IB, Ozkan G (2020) What is your level of nomophobia? An investigation of prevalence and level of nomophobia among young people in Turkey. Community Mental Health, UK.

- Sahu M, Gandhi S, Sharma MK (2019) Mobile phone addiction among children and adolescents: A systematic review. J Addict Nurs 30(4): 261-268.

- Nikhita CS, Jadhay PR, Ajinkya SA (2015) Prevalence of mobile phone dependence in secondary school adolescents. J Clin Diagn Res 9(11): 6-9.

- Davey S, Davey A (2014) Assessment of smartphone addiction in Indian adolescents: A mixed method study by systematic-review and meta-analysis approach. Int J Prev Med 5(12): 1500-1511.

- Davey S, Davey A, Ragav SK, Singh JV, Singh N, et al. (2018) Predictors and consequences of “phubbing” among adolescents and youth in India: An impact evaluation study. J Family Community Med 25(1): 35-42.

- Lee H, Kim JW, Choi TY (2017) Risk factors for smartphone addiction in Korean adolescents: Smartphone use patterns. Journal of Korean Medical Science 32(10): 1674-1679.

- Cha SS, Seo BK (2018) Smartphone use and smartphone addiction in middle school students in Korea: Prevalence, social networking service, and game use. Health Psychol Open 5(1): 2055102918755046.

- Chung JE, Choi SA, Kim KT, Yee J, Kim JH, et al. (2018) Smartphone addiction risk and daytime sleepiness in Korean adolescents. J Paediatr Child Health 54(7): 800-806.

- Lee SY, Lee D, Nam CR, Kim DY, Park S, et al. (2018) Distinct patterns of internet and smartphone-related problems among adolescents by gender: Latent class analysis. J Behav Addict 7(2): 464-465.

- Pan YC, Chiu YC, Lin YH (2019) Development of the problematic mobile gaming questionnaire and prevalence of mobile gaming addiction among adolescents in Taiwan. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 22(10): 662-669.

- Field T (2018) Internet addiction in adolescents: A review. Journal of Addictions and Therapies 1: 1-11.

- Yang SY, Lin CY, Huang YC, Chang JH (2018) Gender differences in the association of smartphone use with the vitality and mental health of adolescent students. J Am Coll Health 66(7): 693-701.

- Nishida T, Tamura H, Sakakibara H (2019) The association of smartphone use and depression in Japanese adolescents. Psychiatry Res 273: 523-527.

- Cheung T, Lee RLT, Tse ACY, Do CW, So BCL, et al. (2019) Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking 22: 714-723.

- Kwon M, Kim DJ, Cho H, Yang S (2013) The smartphone addiction scale: Development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS One 8(12): e83558.

- Kim D, Lee Y, Lee J, Nam JK, Chung Y (2014) Development of Korean smartphone addiction proneness scale for youth. PLoS One 9(5): e97920.

- Foerster M, Roser K, Schoeni A, Roosli M (2015) Problematic mobile phone use in adolescents: Derivation of a short scale MPPUS-10. Int J Public Health 60(2): 277-286.

- Guseller CO, Cosguner T (2012) Development of a problematic mobile phone use scale for Turkish adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking 15: 205-211.

- Lin CY, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH (2018) Psychometric evaluation of Persian nomophobia questionaire: Differential item functioning and measurement invariance across gender. J Behav Addict 7: 100-108.

- Youn H, Lee SI, Lee SH, Kim JH, Park EJ, et al. (2018) Exploring the differences between adolescents’ smartphone addiction. J Korean Med Sci 33(52): e347.

- Bruni O, Sette S, Fontanesi C, Baiocco R, Laghi, et al. (2015) Technology use and sleep quality in preadolescence and adolescence. J Clin Sleep Med 11(12): 1433-1441.

- De Sola Gutierrez J, Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Rubio G (2016) Cell phone addiction: A review. Front Psychiatry 7: 175.

- Shim JY (2019) Christian spirituality and smartphone addiction in adolescents: A comparison of high-risk, potential-risk, and normal control groups. J Relig Health 58(4): 1272-1285.

- Parashkouh NN, Mirhadian L, EmamiSigaroudi A, Leili EK, Karimi H (2018) Addiction to the internet and mobile phones and its relationship with loneliness in Iranian adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health.

- Ha JH, Chin B, Park DH, Ryu SH, Yu J (2008) Characteristics of excessive cellular phone use in Korean adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav 11(6): 783-784.

- Oberst U, Wegmann E, Stodt B, Brand M, Chamarro A (2017) Negative consequences from heavy social networking in adolescents: The mediating role of fear of missing out. J Adolesc 55: 51-60.

- Lee JE, Jang SI, Ju YJ, Kim W, Lee HJ, et al. (2017) Relationship between mobile phone addiction and the incidence of poor and short sleep among Korean adolescents: A longitudinal study of the Korean children & youth panel survey. J Korean Med Sci 32(7): 1166-1172.

- Mahmoodi H, Nadrian H, Shaghaghi A, Jafarabadi MA, Ahmadi A, et al. (2018) Factors associated with mental health among high school students in Iran: does mobile phone overuse associate with poor mental health? J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs 31(1):6-13.

- Dewi RK, Efendi F, Has EMM, Gunawan J (2018) Adolescents’ smartphone use at night, sleep disturbance and depressive symptoms. International Journal of Adolescent Mental Health.

- Bilgrami Z, McLaughlin L, Milanaik R, Adesman A (2017) Health implications of new-age technologies: A systematic review. Minerva Pediatr 69(4): 348-367.

- Xie X, Dong Y, Wang J (2018) Sleep quality as a mediator of problematic smartphone use and clinical health symptoms. J Behav Addict 7(2): 466-472.

- Lissak G (2018) Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on children and adolescents: Literature review and case study. Environ Res 164: 149-157.

- Zou Y, Xia N, Zou Y, Chen Z, Wen Y (2019) Smartphone addiction may be associated with adolescent hypertension: A cross-sectional study among junior school students in China. BMC Pediatrics 19(1): 310.

- Tsimtsiou Z, Haidich AB, Drontos A, Dantsi F, Sekeri Z, et al. (2017) Pathological internet use, cyberbullying and mobile phone use in adolescentce: A school-based study in Greece. Int J Adolesc Med Health 30(6).

- Pedrero Perez EJ, Rodriguez Monje MT, Ruiz Sanchez DeLeon JM (2012) Mobile phone abuse or addiction: A review of the literature. Adicciones 24(2): 139-152.

- Randler C, Wolfgang L, Matt K, Demirhan E, Horzum MB, Besoluk S (2016) Smartphone addiction proneness in relation to sleep and morningness-eveningness in German adolescents. J Behav Addict 5(3): 465-473.

- Tateno M, Teo AR, Ukai W, Kanazawa J, Katsuki R, et al. (2019) Internet addiction, smartphone addiction, and Hikikomori trait in Japanese young adult: Social isolation and social network. Front Psychiatry 10: 455.

- Derevensky JL, Hayman V, Gilbeau L (2019) Behavioral addictions: Excessive gambling, gaming, internet and smartphone use among children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am 66(6): 1163-1182.

- Roh D, Bhang SY, Choi JS, Kweon YS, Lee SK, et al. (2018) The validation of implicit association test measures for smartphone and internet addiction in at-risk children and adolescents. J Behav Addict 7(1): 79-87.

- Liu CH, Lin SH, Pan YC, Lin YH (2016) Smartphone gaming and frequent use pattern associated with smartphone addiction. Medicine (Baltimore) 95(28): e4068.

- Kim HJ, Min JY, Min KB, Lee TJ, Yoo S (2018) Relationship among family environment, self-control, friendship quality, and adolescents’ smartphone addiction in South Korea: Findings from nationwide data. PLoS One 13(2): e0190896.

- Extremera N, Quintana Orts C, Sanchez Alvarez N, Rey L (2019) The role of cognitive emotion regulation strategies on problematic smartphone use: Comparison between problematic and non-problematic adolescent users. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(17): E3142.

- Li X, Hao C (2019) The relationship between parental attachment and mobile phone dependence among Chinese rural adolescents: The role of alexithymia and mindfulness. Front Psychol 10: 598.

- Kwak JY, Kim JY, Yoon YW (2018) Effect of parental neglect on smartphone addiction in adolescents in South Korea. Child Child Abuse Negl 77: 75-84.

- Emirtekin E, Balta S, Sural I, Kircaburun K, Griffiths MD, et al. (2019) The role of childhood emotional maltreatment and body image dissatisfaction in problematic smartphone use among adolescents. Psychiatry Res 271: 634-639.

- Franchina V, Vanden Abeele M, van Rooij AJ, Lo Coco G, De Marez L (2018) Fear of missing out as a predictor of problematic social media use and phubbing behavior among Flemish adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(10). Pii: E2319.

- Coskun S, Karayagiz Muslu G (2019) Investigation of problematic mobile phones use and fear of missing out (FoMO) level in adolescents. Community Ment Health J 55(6): 1004-1014.

- Wang P, Zhao M, Wang X, Xie X, Wang Y, et al. (2017) Peer relationship and adolescent smartphone addiction: The mediating role of self-esteem and the moderating role of the need to belong. J Behav Addict 6(4): 708-717.

- Li C, Liu D, Dong Y (2019) Self-esteem and problematic smartphone use among adolescents: A moderated mediation model of depression and interpersonal trust. Front Psychol 10: 2872.

- Yen CF, Tang TC, Yen JY, Lin HC, Huang CF, et al. (2009) Symptoms of problematic cellular use, Functional impairment and its association with depression among adolescents in Southern Taiwan. J Adolesc 32(4): 863-873.

- Park SY, Yang S, Shin CS, Jang H, Park SY (2019) Long-term symptoms of mobile phone use on mobile phone addiction and depression among Korean adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(19). Pii: E3584.

- Kim SG, Park J, Kim HT, Pan Z, LeeY, et al. (2019) The relationship between smartphone addiction and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity in South Korean adolescents. Ann Gen Psychiatry 18: 1.

- Garcia Oliva C, Piqueras JA (2016) Experiential avoidance and technological addictions in adolescents. J Behav Addict 5(2): 293-303.

- Field T (2020) Facebooking in adolescents: A narrative review. In review.

- Li M, Jiang X, Ren Y (2016) The effect of home-based daily journal writing in Korean adolescents with smartphone addiction. J Korean Med Sci 31(5): 764-769.

-

Tiffany Field. Cell Phone Addiction in Adolescents: A Narrative Review. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 3(4): 2020. OAJAP. MS.ID.000568.

Addiction, Adolescents, Physical Problems, Psychological Problems, Anxiety, Methodological Limitations, Nomophobic, Hyperactivity, Pathological Gambling, Low Mood, Health Risks, Addictive Behavior, Mental Health, Depression, Sleep Disturbances, High Blood Pressure, Obesity, Low HDL Cholesterol, Poor Stress, Parental Addiction, Phubbing Behavior

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.