Research Article

Research Article

Alcohol as a Coping Mechanism for Social Anxiety

Amanda Beccaria*, Stephen E Berger and Tica Lopez

Department of Psychology, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Irvine, USA

Amanda Beccaria, Department of Psychology, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Irvine, California, USA.

Received Date: October 29, 2019; Published Date: November 08, 2019

Abstract

Alcohol abuse has become a significant issue on college campuses, particularly heavy episodic drinking commonly known as binge drinking. Various factors have been studied in relation to the causal and subsequent factors of alcohol abuse on college campuses, including motives, contexts, and psychological conditions related to college students’ use of alcohol. One common impetus for college students to use alcohol is to deal with anxiety. One group of students who are particularly susceptible to experience anxiety are those who suffer from social anxiety. However, research lacks focus on the potential impact of social anxiety as a motivator for drinking behaviors. There were several significant findings related to Social Anxiety scores. A major finding was that the strongest relationship found was that students suffering from social anxiety utilize alcohol in the context of coping with their negative emotions. This is a new and important detail in understanding the ways in which those suffering from social anxiety try to cope with their negative emotions and their vulnerability to substance abuse. Significant gender differences also were obtained that indicated female students were more likely to drink to cope with negative emotions. In addition, findings indicated female students living off-campus reported higher levels of social anxiety than females living on-campus, and vice versa for males students. However, analyses do not permit tying these gender differences to differences in use of alcohol. Finally, there were differences between the women and men depending upon their employment status (i.e., full-time, part-time, unemployed). Trends in the analyses provided for implications of clinicians and offer direction in the construction of future research about social anxiety and alcohol use by college students. It appears that for students experiencing social anxiety, the relationships among social anxiety, use of alcohol for coping and various life situations in which students are living all interact to impact their use of alcohol.

Keywords: Social Anxiety; Alcohol, Coping; Employment; Campus housing

Introduction

Alcohol consumption has increased in recent decades internationally, with all or most of the increase occurring in developing countries [1]. It was also reported that people who begin drinking at a young age are at higher risk of developing alcoholrelated problems in the future. In the United States, over 18 million people are considered to suffer from alcohol dependence, more commonly referred to as alcoholism, or alcohol abuse (National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [2]. The primary difference between alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence is that those who suffer from alcohol dependence have a physiological and/or psychological need to abuse the substance [3]. According to the United States Department of Health and Human Services [4] individuals are most likely to drink the heaviest in their late teens and early twenties.

Across the United States, alcohol abuse has become a significant issue on college campuses, particularly heavy episodic drinking commonly known as binge drinking. According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), about four out of five college students drink alcohol [2]. In addition, about half of college students who drink consume alcohol by binge drinking (National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [2]. Binge drinking continues to have negative consequences nationally.

Approximately 1,825 college students between the ages of 18 to 24 die each year due to alcohol-related injuries, more than 690,000 college students are assaulted by another student who has been drinking, and approximately one million college students are affected by sexual abuse (e.g., sexual assault, date rape), unintentional injury, health problems, suicide attempts, and academic problems (e.g., missing class, poor performance) [2]. Understanding what may influence college students to binge drink will allow for preventative care against such negative consequences.

Multiple dimensions have been studied in relation to the causal and subsequent factors of alcohol abuse. In one study [5], the researchers identified multiple reasons for substance abuse. Such reasons may include social and recreational reasons, anger and frustration, getting away from problems, experimentation, among others. Another study [6], found that self-image goals, or goals in which people seek to construct, maintain, and defend positive selfviews, had a direct effect on alcohol-related problems of college students. The use of alcohol to deal with anxiety has also been investigated [7]. However, among the broad range of motives that have been assessed, the influence of social anxiety has typically been subsumed with other anxiety disorders and has lacked individual focus in the literature.

College campuses offer individuals unique academic and interpersonal experiences. College students are often in an entirely new environment, with little interpersonal connections and advancing academic pressures. It is not surprising that many students are often anxious about their academic performance and/ or social impressions and relationships. In a 2008 survey, it was found that anxiety disorders were one of the most common mental health issues among college students, including social anxiety, or social phobia [8].

Social Anxiety is currently defined as “a marked fear or anxiety about one or more social situations in which the individual is exposed to possible scrutiny by others” [9]. These situations may include social interactions, performing in front of others, and being observed. The individual must also fear that “he or she will act in a way or show anxiety symptoms that will be negatively evaluated… and will lead to rejection or offend others” [9].The criteria for diagnosis includes that the social situation also “almost always provokes fear or anxiety,” and, thus, it is often “avoided or endured with intense fear or anxiety” [9].

In any given year, about 15 million United States adults are diagnosed with Social Anxiety Disorder. According to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA), it is not unusual for individuals diagnosed with Social Anxiety Disorder to drink excessively to cope with or escape their symptoms. In fact, about 20 percent of people with Social Anxiety disorder also suffer from either alcohol dependence or abuse [8]. One study found that the lifetime prevalence for individuals with comorbid social anxiety disorder and alcohol-use disorder was 2.4 percent, and in 79.7% of comorbid cases, social anxiety occurred before alcohol dependence developed [10].

Utilizing alcohol, or any substance, to cope with or escape from psychological symptoms reflects the self-medication model for the co-morbidity of alcohol-use disorders and anxiety [2]. This model suggests that individuals with anxiety disorders attempt to relieve their symptoms by drinking alcohol, which may eventually lead to alcohol-use disorders. The individual is thought to be motivated to drink based on the expectation that drinking will lead to more positive affective consequences than if they chose not to drink [11]. Investigators with the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) found that the highest rates of alcohol-based self-medication were among participants with generalized anxiety disorders, social phobia (or social anxiety), and panic disorder with agoraphobia [2].

Statement of the Problem

Within the clinical population, it is important to recognize how psychological disorders and the co- morbidity of alcohol abuse are associated. Students across college campuses are facing significant social and academic pressures. Binge drinking has become a growing problem across college campuses, and it comes with significant risk. Young students who participate in binge drinking may suffer sexual abuse (e.g., sexual assault, date rape), unintentional injury, health problems, suicide attempts, and academic problems (e.g., missing class, poor performance [2]. Unfortunately, a majority of the literature regarding drinking motives on college campuses has only examined social influence as a dominant factor in increasing alcohol abuse.

However, additional psychological factors such as social anxiety may contribute to an individual’s decision to use or abstain from use of alcohol or susceptibility to social pressure.

The purpose of this study was to quantitatively investigate how aspects of social anxiety may affect a college student’s drinking behaviors. The goal was to investigate these variables by having the students rate their experience of social anxiety, including feared social situations, fear of acting in an embarrassing manner, and fear of rejection and/ or scrutiny. The students also rated their alcohol-use behaviors, including frequency (e.g., how many times a week) and intensity (e.g., how many drinks, ability to control). Thus, this study permitted a detailed analysis of specific aspects of social anxiety and the relationship to the use of alcohol to cope with specific sources of anxiety.

Social anxiety and binge drinking remain consistent mental health and behavioral issues for students across universities, colleges, and various institutions. In addition to the self-medication model, there are additional models that suggest no causal relationships between the two disorders (i.e., The Common Factor Model) and that Social Anxiety Disorder is a result of alcohol withdrawal and recent abstinence (Substance- Induced Anxiety Model) [2]. Although these models are accepted among various investigators, there is limited research that directly addresses social anxiety and the influence of alcohol-use behaviors in college students. By investigating the relationship between social anxiety and alcohol abuse, the information may aid in the treatment and understanding of this frequent co-morbidity among the college population.

Null hypotheses

Null hypothesis 1: There is no significant difference between male participants’ and female participants’ alcohol consumption, level of social anxiety, drinking motives, and drinking context.

Null hypothesis 2: There is no significant association between social anxiety scores and the participant’s alcohol consumption, nor with drinking motives, nor drinking context.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited through purposive, convenience, and snowball sampling. A flyer was developed containing a brief description of the study, inclusion criteria, and a link to Qualtrics. com, an online tool for survey administration. This flyer was distributed via snowball sampling. It was distributed via e-mail and social network platforms (i.e., facebook.com) by the researcher and her colleagues to recruit participants in the college population. The recruited individuals were asked to then forward the flyer through e-mail or sharing on their social media site to individuals who also appeared to meet the inclusion criteria.

To be included in the study, the participant must have attended an undergraduate college or university located in the United States. The participant must have attended on-campus classes, and the study did not include students taking primarily online coursework. Participants who take more than 4 credits of coursework online each semester will be excluded from the study. The included participants were between the ages of 18 and 25-years. This age range was chosen due to the developmental differences between young adults and mature adults in their drinking behaviors and motives to drink. In addition, the study utilized measures developed for adolescents and young adults. Effort was made to recruit subjects from diverse backgrounds. In addition, effort was made to obtain an equal gender ratio among participants.

The survey was distributed from April 2016 through May 2016, November 2016 through December 2016, and February 2017 through June 2017. The survey was administered in sections, as the researcher aimed to assess student’s while currently enrolled in fall or spring terms. A total of 101 student began completing the survey. After applying exclusion criteria and non-completion, a total of 43 participants were included for data analysis. The average age of 43 retained participants was 21.1 years (SD=1.87). Of the 43 participants, 24 (55.8%) were female, and 19 (44.2%) were male.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire: Demographic information was collected from respondents related to age, gender, ethnicity, and residence (i.e., on-campus housing versus off-campus housing). Respondents were also asked several questions regarding their education, location, and occupation. They were also asked to identify their on-campus v. on-line course load. The student were also asked to answer two questions regarding their alcohol consumption. The questions included: (1) Over the 30 days (approximately 4 weeks), about how many times per week did you drink alcohol? (2) On average, approximately how many drinks do you have?

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS): Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) was developed to measure participants degree of both their anxiety and avoidance in 24 social situations. Participants rated the degree to which the social situation causes them fear or anxiety on the following 4-point Likert scale: 0 (Not at All), 1 (Mild/Tolerable), 2 (Moderate/Distressing), or 3 (Severe/ Disruptive). Respondents were also asked to rate their degree of avoidance of these social situations using the following 4 point Likert scale: 0 (Never), 1 (Occasionally/1-33%), 2 (Often/34-67%), or 3 (Usually/68-100%).

The LSAS has been demonstrated to have high internal consistency with scores ranging from .90 to .98 respectively between total and subscales [12]. The LSAS also demonstrates the ability to discriminate between patients with Social Anxiety Disorder and individuals with Generalized Anxiety [12].

Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (DMQ-R): Respondents’ motives for drinking were assessed using revised version of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire [13]. The DMQ-R is a 20–item measure that assesses for four motives for drinking. The four subscales include: social, enhancement, conformity, coping [14].

Drinking Context Scale (DCS): The Drinking Context Scale (DCS) is a 23-item self-report measure assessing the likeliness of an individual to drink excessively within three contexts: social/ convivial contexts (e.g., at a party, at a bar), intimate contexts (e.g., on a date, before having sex), and negative coping contexts (e.g., after a fight, when I’m sad/angry). Each item is rated by the respondent on the following 5-point Likert scale: 1 (Extremely low), 2 (low), 3 (moderate), 4 (high), or 5 (Extremely high). Each subscale (i.e., social/convivial contexts, intimate contexts, and negative emotion contexts) demonstrates internal consistency for convivial drinking, negative coping drinking, and intimate drinking at .82, .85, and .81 respectively [15]. For the purposes of statistical analysis, the scale was scored using both long and short form templates. The long form utilizes all 23-items in the following way: 5 items on the negative coping subscale, 10 items on the convivial subscale, and 8 items on the intimate subscale. The short form utilizes 15 of the total items, with 5 items on each of the three subscales.

Procedures

The respondents were asked to complete a demographic questionnaire and three surveys using Qualtrics.com, an online tool for survey administration and data collection. The Demographic Questionnaire and three surveys were estimated to take each participant approximately 20 minutes to complete. Respondents were asked for their voluntary participation in the study based on inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Each participant was given a written informed consent explaining the purpose and procedures of the study. Upon clicking the link to Qualtrics.com, the respondent immediately arrived at an “Agreement Page.” Informed consent was obtained using this “Agreement Page” prior to completing the online measure. Participants were informed that they may withdraw from the study at any time during the course of their participation without penalty. All of the information gathered was anonymous, and no identifying information was obtained. To ensure confidentiality, the demographic questionnaire was separated from the general survey information. In addition, information was de-identified by assigning each participant with a code number. Only the researcher has access to the files. The files were stored on the researcher’s external hard-drive and was password protected.

Upon completing the study, each participant received a debriefing statement with the researcher’s contact information. Respondents were also entered into a raffle to win a one of three $20 gift cards to Amazon.com as a token of appreciation for their participation. To do this, respondents provided their contact information to be eligible for the gift card drawing. This identifying information did appear on the surveys completed by the respondent. Rather, participants were given the option to submit their name and e-mail address to the researcher through a link after participation. The researcher contacted the winning participant using the provided email address to obtain a mailing address to which the respondent wanted his/her gift card sent.

Results

The following statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS software package. Descriptive statistics were computed on all demographic variables. To test the first hypothesis, two-way Analyses of Variance (ANOVA) using Gender x Housing and with Gender x Employment status were conducted to further study how young men and young women’s alcohol consumption differs based on their social anxiety, drinking

motives, and drinking context and relates to whether they live on-campus or off-campus and whether they are working full-time, part-time or are unemployed. To test the second hypothesis, tests of association between the participants’ social anxiety and his or her drinking motives and drinking context and his or her alcohol consumption were examined using Pearson Correlations.

Demographic statistics

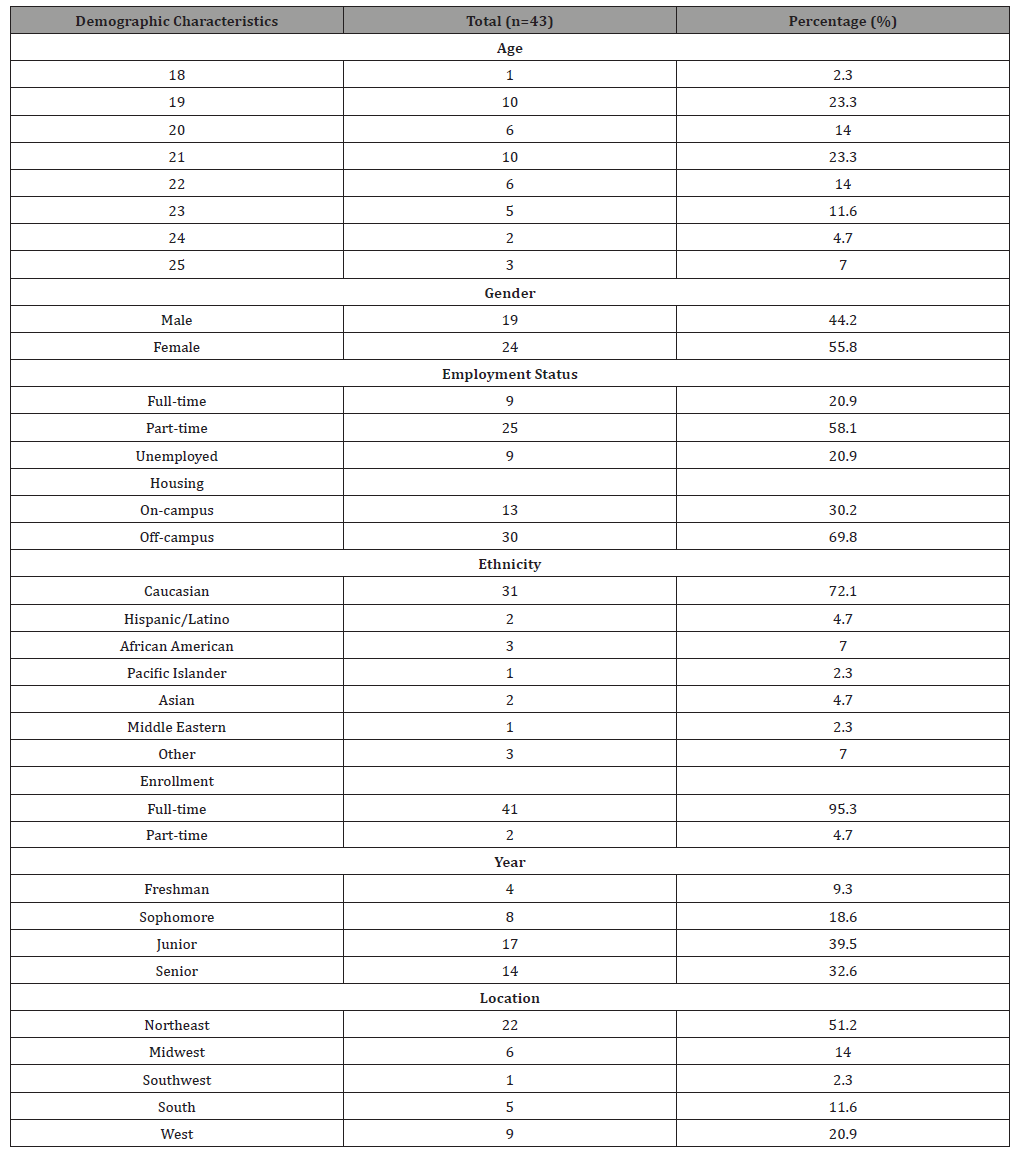

Demographic information is provided in Table 1 below. The average age of the 43 retained participants was 21.1 years (SD=1.87). The age range was 18 to 25 years. Of the 43 participants, 24 (55.8%) were female, and 19 (44.2%) were male. In addition, the employment status of the sample was as follows: fifty-eight percent of participants worked part-time, and the remaining participants worked full-time (20.9%) or were unemployed (20.9%). A majority of participants lived off-campus (69.8%), and the remaining lived on-campus (30.2%).

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of Sample.

Null hypothesis 1: There is no significant difference between male participants’ and female participants’ alcohol consumption, level of social anxiety, drinking motives, and drinking context.

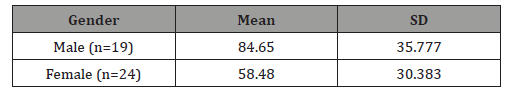

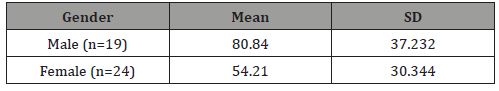

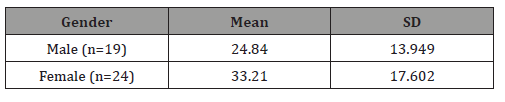

A total of five significant gender effects were obtained. Thus, null hypothesis one can be rejected in part as there were several main effects of gender found plus several interactions of gender with housing status and employment status. A significant difference was found between the genders in number of credits the male and female participants attempted, F (1, 43) = 6.373, p=.016. In addition, a significant difference was found between the genders in the number of credits the male and female participants completed, F (1,46) = 6.637, p = .014. The means and standard deviations for these two significant differences are presented in Tables 2 and 3. It can be seen in Tables 2&3 that the males had attempted and completed more credits than the female participants. The males completed of 95.55% if the credits they attempted, and the females completed 92.7% of the credits they attempted.

Table 2: Means and standard deviations for each gender of the number of Credits Attempted.

Table 3: Means and standard deviations for each gender of the number of Credits Completed.

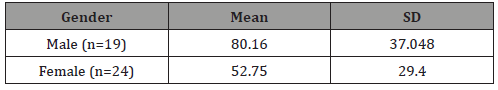

Table 4: Means and standard deviations for each gender of the number of Credits completed on-campus.

A significant difference was also found between male and female participants’ completion of credits on-campus versus online, F (1,43) =7.325, p = .01. The means and standard deviations for each gender are presented in Table 4. It can be seen in Table 4 that males had completed more of their credits on-campus than did the females. In comparing Tables 2&4, it can be seen that males completed 94.7% of their credits on- campus, whereas the women completed 90.2% of their credits on-campus.

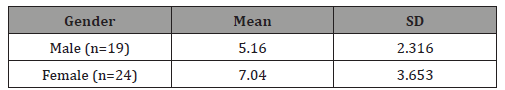

A significant effect was also found between male and female participants’ score on the Fear subscale on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS), F (1, 43) =6.298, p=.017. The means and standard deviations for this gender difference are presented in Table 5. It can be seen in Table 5 that the female participants rated themselves higher on the experience of Fear related to social anxiety. The fear subscale indicates participants rating the degree to which a social situation causes them fear or anxiety.

Table 5: Means and standard deviations for each gender on the Fear subscale scores of the LSA.

A significant gender difference was also found on participants’ use of drinking in the context of Negative Coping, based on subscale scores on the Drinking Context Scale (DCS), F (1,43) = 4.372, p = .043. Means and standard deviations for this gender difference are presented in Table 6. As shown in Table 6, females also rated themselves higher than males did on use of alcohol when coping with negative emotions.

Table 6: Means and standard deviations for each gender on the number of Negative coping subscale scores on DCS.

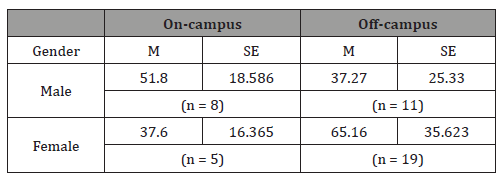

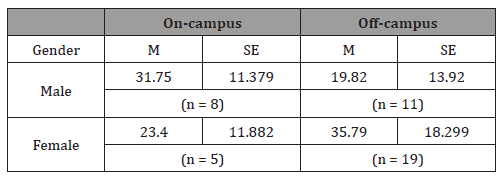

A two-way ANOVA was conducted that examined the relationships of gender and housing with social anxiety. A statistically significant interaction was found for the effects of gender and housing type (on-campus or off-campus) on Total Social Anxiety score (LSAS), F (1,42) = 4.332, p=.044. Additional two-way ANOVAs were conducted with each subscale (fear and avoidance) of the LSAS as dependent variables. There were no significant effects found for gender and housing on the Avoidance subscale. However, a significant interaction effect was found for gender and housing on the Fear subscale, F (1,42) = 5.260, p=.027. Thus, the significant effect on Total Social Anxiety Score is the result of the significant differences on the fear sub-scale. The means and standard deviations for Total Social Anxiety score and the fear subscale are presented in Tables 7&8. As shown in Tables 7&8, females living off-campus reported the highest levels of both total social anxieties, and more specifically, for the fear component of the social anxiety scale. In addition, males living on-campus reported higher levels of social anxiety and fear than females living on-campus.

Table 7: Means and standard error for each gender on Total scores on the LSAS.

Table 8: Means and standard error for each gender on the Fear subscale scores on the LSAS.

A two-way ANOVA was conducted that examined the relationships of gender and employment status (i.e., full-time, part-time, unemployed) to drinking motives (i.e., social, coping, enhancement, conformity).

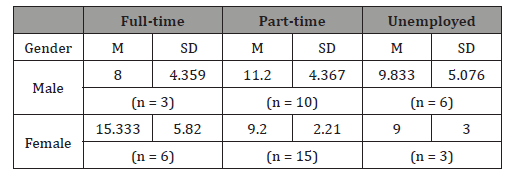

There was one significant effect found of gender and employment status on motivation to drink for coping purposes, F (2,42) = 4.136, p=.024. Means and standard deviations for the relationship of gender and employment status to motives and contexts of alcohol use are presented in Table 9. As shown in Table 9, male participants with employment status of full-time employment or who were unemployed reported drinking for coping less than males working part-time. In addition, part-time employed males report using alcohol for coping more often than part-time employed females. It appears the reverse is true for full-time employed males who report the least use of alcohol for coping, and with full-time employed females reporting the highest degree of motivation to drink for coping purposes.

Table 9: Means and standard deviations for each gender on the Coping subscale scores on DMQ-R.

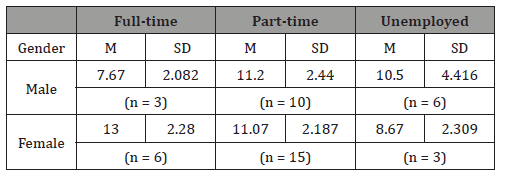

A two-way ANOVA was conducted to examine the relationships of gender and employment status to drinking contexts (i.e., negative coping, convivial, intimate). A significant effect was found for the interaction of gender and employment status with drinking in convivial, (social contexts), F (2,42) = 4.206, p = .023.

Means and standard deviations of the relationships of gender and employment status to drinking contexts are presented in Table 10. As can be seen in Table 10, male participants with employment status of full-time employment or who were unemployed reported drinking in convivial contexts less than males working part- time. In addition, part-time employed males report consuming alcohol in convivial contexts more often than part-time employed females. It appears the reverse is true for full-time employed males who report the least use of alcohol in convivial contexts, and with fulltime employed females reporting the highest degree of alcohol use in convivial contexts.

Table 10: Means and standard deviations for each gender on the Convivial subscale scores on DCS.

Null hypothesis 2: There is no significant association between social anxiety scores and the participant’s alcohol consumption (# of drinks) nor with drinking motives nor drinking context.

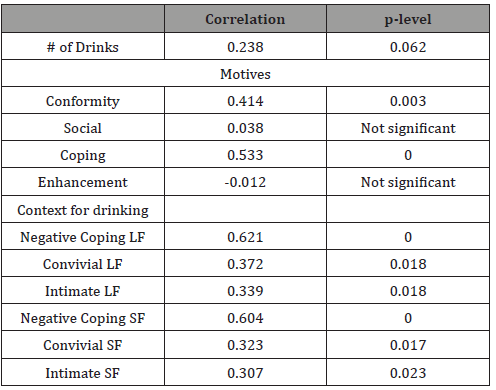

Correlations of Social Anxiety Total Score with # of drinks, and the measures DMQ-R and DCS to test this hypothesis, Pearson correlation coefficient were computed between Social Anxiety Total scores on LSAS and the various drinking motives and contexts for drinking that were assessed in this study. The correlations between each of the components of Social Anxiety (Avoidance and Fear) were highly correlated with Total Social Anxiety Score (.961 and .966 respectively), thus producing basically identical correlations. Therefore, only the correlations of motive to use alcohol and context of using alcohol with Social Anxiety Total score are reported here and are presented in Table 11. As can be seen in Table 11, almost all of the correlations with Social Anxiety were statistically significant. Thus, null hypothesis 2 can be rejected as social anxiety generally was associated with motives for drinking as well as the contexts for drinking that were examined in this study.

There are several notable features from the correlations presented in Table 11. First, the relationship between social anxiety and number of drinks reported approached conventional levels of statistical significance. This finding will be examined in greater detail in the Discussion section. For the moment, it should be noted that a relationship between social anxiety and amount of use of alcohol may exist but might not be sufficiently strong to manifest as statistically significant in this study because of the relatively small number of subjects. Therefore, the possibility of such a relationship should not be dismissed based on these results.

Second, social anxiety was associated with two of the four measures of motives for using alcohol. Thus, the higher the person’s score on the social anxiety measure, the more he or she said they used alcohol to conform to peers, and the more the student reported using alcohol to cope with their anxiety (fear) in social situations.

Table 11: Correlations of Social Anxiety Total on LSAS.

It can also be seen in Table 11 that almost identical results were obtained for the short form of context for alcohol use as did the long form. Based on the correlations in Table 11, the short form might lose a little bit of specificity, but the difference between the two forms is practically negligible. Finally, Table 11 shows that social anxiety was significantly associated with drinking in convivial, or social, contexts as well as in romantic encounters, but was most highly associated with negative coping. Negative coping contexts are circumstances in which an individual is experiencing negative emotions and chooses to drink as a coping tool. Examples of items on this subscale include indicating that the person uses alcohol when: “having trouble relaxing, winding down,” “when I’m lonely or homesick.”

Discussion

This study attempted to examine whether there is an association between social anxiety and drinking for college students. Although all efforts were made to collect data from students with varying demographic characteristics, the findings in this study were obtained primarily from Caucasian students. No statistically significant relationships were found with regard to social anxiety scores and number of drinks, although the relationship of social anxiety scores and amount of drinking approached conventional levels of statistical significance. However, the study found several significant relationships between social anxiety, gender, housing type, employment status, and both motives and context for engaging in alcohol use.

Social Anxiety, drinking, drinking motives and coping mechanisms

Findings indicated a likelihood that there is a relationship between social anxiety and drinking. Although the correlation was not significant, these correlations approached the conventional levels of significance. This may mean that there is a relationship between higher levels of social anxiety and the use of alcohol by college students, but the relationship may not be a large one when assessed in such simple way of a linear correlation coefficient. Thus, the magnitude of the correlation obtained here may be a result of a relatively low number of participants in this study making the study insensitive to detecting this relationship, and thus a larger sample size may demonstrate a significant relationship, such that higher levels of social anxiety may result in an increased number of drinks per occasion, or binge drinking.

The findings also demonstrated a significant relationship between social anxiety and motives to drink, including conformity and coping as assessed in this study. One possible interpretation is that those with social anxiety may be motivated to drink due to conformity, as he or she may be fearful of judgement or rejection if he or she does not participate in drinking activities. These findings are consistent with the results of the Buckner, Schmidt, and Eggleston study [16] that indicated that when individuals with social anxiety drink, they appear to consume alcohol in an attempt to regulate negative feelings, conflict with others, and in situations involving social pressures to drink. These findings are also consistent with Norberg et al. [17] who found that coping and conformity motives mediated the relationship between social anxiety and alcoholrelated problems. However, the results of the Norberg et al. study were found only for women, not for men. This may be reflective of gender findings in this study, that women are more likely to drink to cope with negative emotional experiences than men.

The findings also indicate a relationship between social anxiety and all three drinking contexts (i.e., negative coping, convivial, intimate). These three findings can appear to overlap with one another with regard to social anxiety, in that both convivial and intimate contexts involve social interactions, and those with social anxiety have demonstrated on both motive and contexts scales to utilize alcohol as a coping tool. Drinking in a convivial context may also relate to the significant findings that individuals experiencing social anxiety are motivated by conformity. Terlecki, et al. [18] had hypothesized that social anxiety would be positively related to drinking on all three subscales. They found that students with high social anxiety reported heavier drinking in Negative Emotion situations and Personal/Intimate situations as compared to students with low social anxiety. However, contrary to the researcher’s hypotheses, students with high social anxiety did not drink significantly more than students with low social anxiety in social/convivial situations.

Gender differences

Findings indicated that male and female college students differ in experiences related to social anxiety and potential impact on their academic functioning. It was found that females rated themselves higher than males in experiencing fears related to social anxiety and the use of alcohol to cope with these negative emotional experiences. These components may impact female student’s ability to complete attempted credits in various ways, as it was found that females attempted and completed less credits than male students – although the differences in percentages were small, the differences were statistically significant. One possible interpretation of these results regarding social anxiety fear of the female college students may be related to increased fear in the classroom, that may impact ability to attend class, ask desired questions, participate adequately in group work, do presentations etc. Another possible interpretation of these results may be the impact of using alcohol to cope with negative emotions on ability to complete coursework. This may also suggest why more males completed coursework on-campus, while females may opt into online coursework to potentially avoid social situations that may induce fear. Again, the differences observed in this study were small but statistically significant, and a larger sample might provide a better image of how big the problem might be.

Another possible interpretation of differences with regard to fear is that females often report higher levels of negative feelings than males on self-report inventories. This is because males notoriously tend to engage in socially desirable responding of denying negative emotional experiences on such measures. However, it is to be noted that male participants in this study did differentially report negative feelings related to living on-campus and off-campus. It was found the on-campus males reported higher levels of fear than females living on-campus. Thus, although males generally reported lower levels of negative feelings than the females, a simple social desirability effect is clearly not present in this data.

Employment status, drinking motives and context of drinking

Similar to findings in gender differences, females reported the highest levels of motivation to drink to cope with negative feelings. These findings are consistent with Park and Levenson [19] who also found that females reported a higher frequency of drinking to cope with negative emotions than males. In this study, it was found that females who work full-time rated themselves the highest for using alcohol as a coping tool.

One possible interpretation for this finding is that females who work full-time may perceive that there is less time to engage in healthy coping with a more demanding schedule, and the availability of alcohol to college students makes it a convenient tool. Park and Levenson [19] also discussed findings that females who did not drink to cope with negative feelings also endorsed utilizing more emotion-focused coping than females who did not drink to cope. The women in this study who worked full time may find the stress of full-time work and academic demands to be an especially stressful combination.

Findings also indicated that females who work full-time are more likely than males to engage in drinking in convivial contexts. This may relate back to the gender findings that females endorsed higher rates of fear related to social anxiety and coping with negative emotions. Thus, in convivial, or social, context, females are more likely to engage in drinking for coping purposes. Future research could look more closely at this factors that possibly operate in combination with each other.

When comparing Tables 9&10, a significant contrast in the data is observed. Full-time employed females reported the highest use of alcohol for coping or in convivial contexts, whereas the fulltime employed males report the lowest use of alcohol to cope or in convivial contexts. This may be consistent with results from a study conducted by Deenhardt and Murphy [20] that found there was a gender difference in distress tolerance among both African American and European American students, with men reporting higher distress tolerance than women across both ethnic groups. This suggests that women of both ethnic groups experience less tolerance for experiencing negative psychological states than men. It may be that the female students in this study also experiences less distress tolerance than the male students. Finally, these findings provide some support for the findings of Butler et al. [21] that working more hours (full time v. part time or unemployed) is related to greater alcohol consumption, but the findings in this study indicate that this phenomenon is more complex and is different for males than for females.

Gender, housing type and social anxiety

The findings indicate a relationship of gender and housing type on social anxiety experiences. It was found that males living on-campus had higher levels of social anxiety than males living offcampus, and vice versa for the females. Females living off-campus had the highest levels of reported levels of social anxiety. These findings were consistent for both total score on social anxiety (LSAS) and the fear subscale. One interpretation of these findings is that more secure males may feel freer to live off-campus, as they report lower levels of anxiety compared to the males living oncampus. For females in this study, this explanation does not appear to apply, and very different factors appear to be operating for the females than for the males. Females living off campus reported higher levels of fear, yet they choose to live off campus. Thus, the inner security issues (at least social anxiety as assessed in this study) that appear to apply to the males cannot be operative with the females. It is difficult to think that the women who choose to live off-campus are more insecure to begin with than those who choose to live on-campus. It appears the price for females asserting their independence to live away from campus is that they live in a more fearful environment.

A second interpretation may be that females who have high levels of social anxiety are more likely to live off-campus as an attempt to avoid the consistent social atmosphere as living in dorms, on-campus apartments, or other on-campus options. However, a lack of significance on the avoidance scale may suggest that females do not tend to avoid situations that induce fear, but, rather, they drink alcohol to cope with it. In addition, males who live on campus may experience high levels of anxiety with regard to potentially feeling social pressures to impress or conform. It is also important to account for students who may attend college close to home and continue to live with their parents, as that factor was not differentiated in the demographic questionnaire used in this study. Future research is needed to identify and measure possible confound variables to further analyze these gender differences.

Clinical Implications

The findings of this study suggest that females who are working full-time are more likely to drink to cope with their negative emotional experiences than women who work part-time or are unemployed. Thus, a clinician working with a female college student who is working full-time should be alert that this patient is more likely to drink to cope with the demands of her academic and employment status. It was also found that males who work part-time are more likely to drink to cope with negative emotions than males working full- time or are unemployed. Thus, a clinician should again be aware of the vulnerability of male college students to drink to cope if they are employed part-time or are unemployed. However, that doesn’t mean that a clinician should automatically assume that a male student working full time is not vulnerable to substance abuse. The data obtained here merely suggests that clinicians be especially alert to this risk with male students who only work part-time or are unemployed.

Findings also suggest that females who live off-campus are more likely to experience social anxiety and fear than females who live on-campus. Clinicians working with female students who live off-campus should be sensitive to signs that underlying any other issues is a sense of fear that may be complicating any other issues that they bring to therapy. In contrast, it was found that males who live on-campus are more likely to experience social anxiety and fear than those males who live off-campus. Thus, again, it is important for clinicians working with college students to consider these variables and vulnerabilities to guide assessment and intervention.

In terms of clinicians working on college campuses, it can be beneficial to engage with students on campus through various forms of outreach in order to provide education about utilizing alcohol to cope with negative emotions and healthy ways to manage student life. Outreach can include classroom presentations, presentations at freshman orientations, pamphlets, workshops, groups, etc. This can include education about social anxiety (and other psychological difficulties), the negative impact of alcohol use on symptoms (psychological, emotional and physical), vulnerable demographics, and healthy coping skills.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There are several limitations to the present study. The first limitation is the sample of students utilized for the study. The sample was collected through snowball sampling and is restricted in various ways, including size and variability (e.g., age, ethnicity, housing). In addition, only students who were attending a college and taking no more than four online credits per semester were included, which does not account for possible differences with college-aged students who may take primarily online coursework. Thus, it would be beneficial for future researchers to utilize a larger and less restricted sample for study.

There are also limitations with regard to the measures used for data collection. All measures utilized in the present study are selfreport measures. Self-report measures may be subject to various complications in a study, including potential dishonesty due to image management and bias or even lack of accurate personal insight. Also, the gender differences and the interactions of gender with factors such as living on- campus v. off-campus as well as employment status indicate that much more research needs to be done regarding social anxiety, gender and various living conditions as they relate to alcohol consumption of college students. In addition, the survey was distributed via an online survey. This does not allow researchers to verify the participants are a part of the target population. It may be beneficial for future researchers to conduct future research in-person on college campuses.

Further, the Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (DMQ-R) does not distinguish measurement on the coping scale between various negative emotional experiences. A modified version (i.e., Modified DMQ-R) of the questionnaire is now available for use, wherein the coping scale is separated into coping with depression and coping with anxiety. It is suggested for future researchers to utilize the modified version for potential clearer understanding about which negative emotional experiences may be influencing binge drinking on college campuses.

Based on the correlations in Table 11, it may be that the short form of the Drinking Context Scale (DCS) might lose a little bit of specificity in comparison to the long form, but the difference between the two forms is practically negligible. It appears that future research may safely use the short form. However, further research would need to be done to determine if there are situations in which the long form is preferred.

Conclusion

This study aimed to add to the literature regarding the impact of social anxiety on college student’s alcohol use behaviors. A major finding in this study indicates that social anxiety was significantly associated with drinking in convivial, or social, contexts as well as in romantic encounters, but was most highly associated with negative coping. Thus, it appears that students who are suffering from social anxiety are utilizing alcohol as a major coping tool. Additional gender differences and some other factors (housing and employment status) were identified as also being relevant to how social anxiety is related to various life circumstance. These trends in the data can aid researchers in construction of future studies, in addition to providing information to clinicians working with college populations in terms of both clinical work and psychoeducational purposes.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- (2012) The Alcoholism Guide.

- National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA] (2012) Alcohol Use Disorders.

- American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 4th Washington, USA.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS] (2012). Vital and health statistics: Summary of health statistics for US.

- Patrick (2011) Age-related changes in reasons for using alcohol and marijuana from ages 18 to 30 in a national sample. Psychol Addict Behav 25(2): 330-339.

- Moeller SJ, Crocker J (2009) Drinking and desired self-images: Path models of self-image goals, coping motives, heavy-episodic drinking, and alcohol problems. Psychol Addict Behav 23(2): 334-340.

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, Mohr CD (2009) Coping-anxiety and coping-depression motives predict different daily mood-drinking relationships. Psychol Addict Behav 23(2): 226-237.

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America (2014).

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5th Washington, USA.

- Schneier FR, Foose TE, Blanco C (2010) Social anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorder comorbidity in the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Psychol Med 40(6): 977-988.

- Cox WM, Klinger E (1988) A motivational model of alcohol J Abnorm Psychol 97(2): 168-180.

- Heimberg R, Horner K, Juster H, Safren S, Brown E, et al. (1999) Psychometric properties of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Psychol Med 29(1): 199-212.

- Cooper ML (1994) Motivations of alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment 6(2): 117-128.

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, O Connor RM, Blackwell E, Conrod PJ (2007) Psychometric evaluation of the five-factor modified drinking motives questionnaire- revised in undergraduates. Addict Behav 32(11): 2661-2632.

- O Hare T (2001) The Drinking Context Scale: a confirmatory analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat 20(2): 129-136.

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Eggleston AM (2006) Social anxiety and problematic alcohol consumption: The mediating role of drinking motives and situations. Behav Ther 37: 381-391.

- Norberg MM, Norton AR, Olivier J, Zvolensky MJ (2010) Social anxiety, reasons for drinking, and college students. Behav Ther 41: 555-566.

- Terlecki MA, Ecker AH, Buckner JA (2014) College drinking problems and social anxiety: The importance of drinking context. Psychol Addict Behav 28(2): 545-552.

- Park CL, Levenson MR (2002) Drinking to cope among college students: Prevalence, problems and coping processes. J Stud Alcohol 63(4): 486-497.

- Dennhardt AA, Murphy JG (2011) Associations between depression, distress tolerance, delay discounting, and alcohol-related problems in european american and african american college students. Psychol Addict Behav 25(4): 595-604.

- Butler AB, Dodge KD, Faurote EJ (2010) College student employment and drinking: A daily study of work stressors, alcohol expectancies, and alcohol consumption. J Occup Health Psychol 15(3): 291-303.

-

Amanda Beccaria, Stephen E Berger, Tica Lopez. Alcohol as a Coping Mechanism for Social Anxiety. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 3(1): 2019. OAJAP.MS.ID.000554.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.