Research Article

Research Article

Acculturative Influences on Psychological Well-Being and Health Risk Behaviors in Armenian Americans

Taline Guevrekian1*, Tica Lopez2, Bina Parekh3 and Anindita Ganguly4

1Department of Psychology, Rose City Center, Pasadena, California, USA

2Department of Psychology, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Irvine, California, USA

3Department of Psychology, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Irvine, California, USA

4Department of Psychology, American School of Professional Psychology, Santa Ana, California, USA

Taline Guevrekian, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Irvine, California, USA.

Received Date: October 25, 2020; Published Date: December 16, 2020

Abstract

The acculturative process is often stressful and may lead to various mental health problems. Research on Armenian Americans and their acculturation process is limited. In the present study, the role of acculturation and acculturative stress in predicting depression, anxiety, and alcohol use were examined, in addition to treatment barriers for this population. In the study, the participants completed the Acculturation Rating Scale of Armenian Americans (ARSAA), the Multidimensional Acculturation Stress Inventory (MASI), the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and the Barriers to Accessing Care 3 (BACE-3). A sample of hundred forty-seven Armenian American adults were recruited online. The results of the study found the level of acculturation to be unrelated to depression, anxiety, and alcohol use levels, although it was related to the country of origin and number of years lived in the United States. However, higher levels of acculturative stress were predictive of depression and anxiety levels. Depression was found to be predicted by acculturative stress and education, while anxiety was predicted by income, gender, acculturative stress, and religion. Gender was predicted by alcohol use, while age and marital status played a role in alcohol use levels. Additionally, age affected depression levels and gender impacted barriers to treatment. This study highlights the importance of acculturative stress as a link to depression and anxiety in Armenian Americans. Additionally, the country of origin plays a significant factor in the acculturation level and barriers to treatment. Furthermore, various sociodemographic factors were identified as important factors in explaining the variability in depression, anxiety, alcohol use, and barriers to treatment levels.

Keywords: Acculturation, Acculturative Stress, Health Risk Behaviors, Armenian Americans, Alcohol Use, Depression, Anxiety, Treatment Barriers

Introduction

Armenia, officially the Republic of Armenia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Georgia to the north, Azerbaijan to the east, Iran to the south, and Turkey to the southwest and west. As of 2015, Armenia has a population of 3,010,600 and is the second most densely populated of the former Soviet republics [1]. Armenia has a 3,000-year-old history as a nation and was the first nation to accept Christianity as its official state religion in 301 AD. Armenian is a branch of Indo-European languages. Armenia lost its independence in 1375 and for nearly six centuries was not an independent country. The First Republic of Armenia was declared on May 28, 1918, and by 1922, Armenia had become a Republic of the Soviet Union. On September 21, 1991, the modern Republic of Armenia declared its independence.

Armenian Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have total or partial Armenian ancestry. The Armenian migration to the United States began in the 1890s. The first major wave of Armenian immigration to the United States took place after the Hamidian massacres of 1894-1896 where nearly 200,000 Armenians were massacred in the Ottoman Empire. The second major wave of immigration occurred after the Armenian Genocide of 1915 [2], the first Genocide of the 20th century that claimed the lives of more than 1.5 million Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire. Between the 1960s and 1980s, a large number of Armenians from various countries including Iraq, Lebanon, Iran, Syria, and Turkey immigrated to America. Around the same time, an influx of Armenian immigrants from the Soviet Union began.

According to the 2011 American Community Survey, 483,366 Americans reported partial or full Armenian ancestry [3]. Other sources have stated that this number is an underestimate and that there are up to 1,500,000 Armenians currently living in America [4]. The largest concentration of Americans of Armenian descent appears to be in the greater Los Angeles area including Glendale, Pasadena, and Hollywood. Armenians living in the United States form the second largest community of the Armenian diaspora following the Armenian population in Russia.

Cultural acculturation is a multidimensional process in which individuals take on selected behaviors, values, customs, and language of the dominant culture [5]. The acculturation may occur in various stages, with the immigrant learning the new language first and then taking part in behavioral activities of the culture. Children may learn the language relatively quickly, while adults may take longer as they have already fully socialized into their culture of origin before migration [6]. Immigration to a new country can be difficult for many reasons and, in the process, individuals often experience stress. The immigrant individual or family may experience difficulties overcoming cultural and language barriers; they might also encounter xenophobia and discrimination [7]. They may suffer occupational, economic, and social status changes. These can cause long-lasting psychological distress and behavioral problems including depression and anxiety. Additionally, they may increase engagement in health risk behaviors including alcohol abuse [8].

Cultural assimilation is the process in which members of an ethnic minority take on the cultural characteristics of the dominant cultural group. This assimilation may be voluntary or forced upon an individual or group and may be rather quick or slow depending on the circumstances [9]. Throughout the diaspora, Armenians have developed a pattern of quick acculturation but slow assimilation [10]. Armenians often quickly acculturate to the U.S. culture by learning the language and attending American schools but are often resistant to assimilate aiming to maintain their own schools, churches, associations, language, and networks of intermarriage [10].

Adjusting to the culture of the United States can be stressful and have a long-term impact on the immigrants’ psychological well-being. According to various studies, first generation Hispanic adolescents report more stressors and greater stress appraisal than third-generation adolescents [11,12]. In Asian Americans, being less identified with the mainstream U.S. culture is associated with increased psychological distress and risk for clinical depression [13]. Additionally, acculturation stress evidences a strong negative relationship with psychological well-being and is associated with mental health outcomes [13,14]. Even high acculturation is found to be stressful if the adolescents adopt Western values and behaviors, while their parents remain attached to their culture of origin [15].

Unfortunately, stress associated with acculturation and minority status among Armenian immigrants is understudied. However, the difficulties with acculturation and acculturative stress that other ethnic groups face maybe analogous for Armenian Americans. Though, Armenian Americans have not been specifically studied, it would be important to determine if similar processes and sources of stress are present in this community.

Different ethnic groups have varying views of mental illness. In Asian Americans, there is a strong negative cultural connotation associated with mental illness. Factors such as guilt and shame are often associated with mental illness. Patients with mental illness symptoms often fear being rejected by their relatives and from their community. They may attempt to “save face” or preserve the public appearance of themselves and their family’s reputation by denying or not discussing their moods and/or psychological states [16]. Additionally, the unfair burden, expectation, and pressure of the “model minority myth” or the stereotype that Asian Americans are more academically, economically, and socially successful than any other racial minority groups can have adverse effects in their lives [17]. Similarly, there is a deeply rooted mix of cultural and socioeconomic factors in the Latino community that often stigmatize people with mental illness [18,19]. In the Latino culture, individuals suffering from depression may be perceived as witches or, even, assumed to be going crazy [19]. Additionally, Latino individuals may believe that experiencing depression would disappoint their family members [20]. Differences in primary language between seeker and health care provider as well as linguistic barriers may also present difficulties in mental health utilization [19]. Additionally, the anxiety associated with an individual’s legal status and their fear of potential deportation has a large impact on their help seeking behaviors [21]. Furthermore, Latinos may have stronger beliefs in faith-based and alternative healing practices as opposed to traditional clinical settings [22]. These factors may cause individuals and their families to delay mental health services or to avoid professional help all together [18].

According to the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), Asian Americans have a 17.3% overall lifetime rate of any psychiatric disorder, although they are three times less likely to seek mental health services than Whites [23]. Only 8.6% of Asian- Americans sought any type of mental health services compared to nearly 18% of the general population nationwide [23]. Similarly, a report found that only 20% of Latinos with symptoms of a psychological disorder talk to a doctor about their concerns and only 10% contact a mental health specialist [18].

Médecins Sans Frontières, also known as Doctors without Borders, conducted a study in Armenia to research the general population’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors towards mental health problems. Most Armenian respondents reported that people with mental health problems should be kept in hospital, that they are usually violent and dangerous, or that they cannot do any work [24]. Additionally, they reported that they would be upset or disturbed about working in the same job as someone with mental health problems, that they would not be able to maintain a friendship with someone with a mental illness, or that they would feel upset or disturbed about sharing a room with an individual with mental health problems [24].

These mental health myths in Armenia are similar to those in Western Europe but the consequences are different and directly influence the lives of Armenians living with mental health problems. Many of these Armenian individuals “are hidden away by their family members, who are ashamed of them, and parents seldom refer their children to psychological services out of fear of being labeled as ‘mad, crazy people’ for the rest of their lives” [25]. In Armenia, individuals need the approval of a psychiatrist to receive a driving license or to work for a government department. If an individual has a psychiatrist file, it is likely to be very hard to obtain this approval. Having a family member with mental health problems also leads to indirect consequences as “mental health problems are considered hereditary” [25]. Therefore, many Armenians are likely to try to hide or deny mental illness. Similarly, “in the Arab world, mental illness is often associated with social shame, damaged reputation and/or diminished social status, leading many individuals to avoid or drastically delay seeking help given the risk of these consequences” [26].

Today, mental health care and services are highly underused and millions of people living with mental health conditions do not receive the adequate care they need. Unfortunately, mental illness does not go away on its own. An untreated mental illness is likely to lead to a steady, and often rapid, decline in mental health [27]. An untreated mental illness is likely to cause interferences with one’s ability to cope effectively with life and day-to-day stressors. It may lead to social, occupational, and financial struggles. Certain ethnic groups may ignore their mental health problems until they are too severe or need intensive treatment. Unfortunately, the longer the mental illness persists, the more their treatment options become limited and their recovery journey uncertain [27]. Therefore, the consequences of untreated mental illness can be serious and devastating.

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, there is a definite connection between mental illness and the use of addictive substances including drugs and alcohol [28]. Often, patients try to medicate their disrupting mental health issues or symptoms by using drugs and alcohol. Additionally, individuals may start to use substances in order to manage various stressors in their life. Unfortunately, these addictive and health risk behaviors often do little to address the patient’s underlying issues or mental health symptoms and rather create a new batch of problems [28]. Studies have found that the level of acculturation and immigrant generations affect health risk behaviors. According to the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health, first generation immigrant adolescents reported being less likely to engage in risky behaviors including delinquent or violent behaviors and use cigarettes and illegal substances [29]. However, immigrant adolescents living in the United States for longer periods of time tended to be less healthy and reported greater prevalence of risky behaviors [1].

Statement of Problem

Psychological distress and maladjustment have been examined in immigrant families. It is undeniable that the immigration process may be experienced as a stressful one for many. It may lead to various mental illness problems and/or may initiate health risk behaviors including alcohol use. However, such problems are often unresolved as many individuals prefer to avoid seeing a mental health professional. Although there is a large population of Armenian Americans in Los Angeles County, the research unfortunately is limited to their immigration process and its associated stressors.

The present study investigated the levels of acculturation and acculturative stress of Armenian individuals, both immigrant and U.S. native, and its effects on various mental health issues including depression and anxiety. Additionally, the study examined the health risk behaviors including alcohol use associated with acculturation in Armenian Americans. Furthermore, the study examined the barriers to mental health treatment amongst Armenian Americans. The study examined the role of level of acculturation and acculturative stress in predicting health risk behaviors and barriers to treatment in Armenian Americans in a quantitative manner through the use of established measures for each construct. Studying the specific stressors encountered by Armenian Americans and its implications in mental health issues would provide insight into their acculturation process. Additionally, learning more about the barriers to treatment would allow for culturally appropriate outreach and education. It may serve as an implanted seed to building awareness and reducing the obstacles to quality mental health care for Armenian Americans.

Methods

Participants

A sample of 147 Armenian American individuals living in Los Angeles County participated in this study. Of this sample, 92 identified as female and 55 identified as male. Respondents were all required to be at least 18 years of age, be fluent in English, and self-identify as of Armenian descent. Individuals who did not meet the inclusion criteria for the study had their results discarded from the study. No inclusion or exclusion pertaining to the length of U.S. residency or citizenship was established in order to gather a broader range of data regarding levels of acculturation. Due to the relatively limited access to Armenian individuals, this sample was recruited using convenience and snowball sampling techniques. This sample was also a purposive sample, in that all respondents were individuals of Armenian descent who were either born in or immigrated to the United States. The researcher approached potential participants by generating a post on an independent and unaffiliated Facebook page, which contained a link to the research tool, SurveyMonkey. Acquaintances of the researcher were asked to share the link to the independent account in order to broaden the pool of potential participants and aid in the recruitment process.

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire - The respondents completed a demographic questionnaire including questions about their Armenian descent, country of origin, year of immigration to the United States, length of stay in the United States, age, religion, education level, marital status, annual household income, and gender. The demographic questionnaire allowed respondents to indicate whether they received previous treatment for mental health concerns, believed that they needed treatment but did not seek it, or did not need treatment and did not seek it.

Acculturation Rating Scale for Armenian-Americans (ARSAA) – Modified Version -The ARSAA is a revision of the ARMSA-II created by Cuellar T, et al. [30], assessing acculturation level among Mexican Americans. The ARMSA-II was modified by Ayvazian [31], for use with the Armenian Americans (e.g., changing from “I speak Spanish” to “I speak Armenian;” “My thinking is done in the Spanish language” to “My thinking is done in the Armenian language,” etc.) The ARSAA includes 30-items assessing both behavior measures (e.g., “I write letters in Armenian”), and affective measures (e.g., “I like to identify myself as American”) relating to acculturation. Responses are based on a 5-point Likert scale (1: not at all, 2: very little/not very much, 3: moderately, 4: much/very often and, 5: almost always/extremely often).

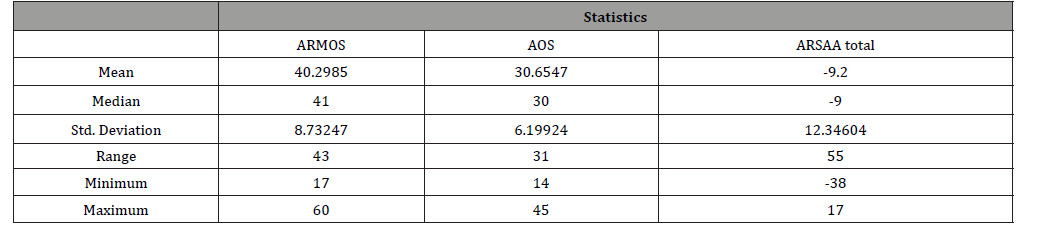

The ARSAA is composed of two subscales; the Armenian Orientation Subscale (ARMOS) consisting of 17 items, and the Anglo Orientation Subscale (AOS) consisting of 13 items. Higher scores within each ARMOS and AOS subscales correspond to a greater degree of cultural orientation to Armenian or Anglo culture respectively. The level of acculturation was measured by subtracting the mean of the ARMOS from the mean of AOS producing difference scores. Positive scores indicate a higher degree of Anglo orientation while negative scores indicate a higher degree of Armenian orientation. The ranges and cutoff scores for the varying acculturation levels are as follows: Level I (Very Armenian Oriented) consisting of acculturation cutting scores < -1.33; Level II (Armenian Oriented / Balanced Bicultural) consisting of acculturation scores > = -1.33 and < = -.07; Level III (Slightly Anglo Oriented) consisting of acculturation scores > -.07 and < 1.19; Level IV (Strongly Anglo Oriented) consisting of acculturation scores > =1.19 and < 2.45; and Level V (Very Assimilated) consisting of acculturation scores > 2.45.

Internal consistency for the ARMOS and AOS subscales were psychometrically tested by Ayvazian [31]. The scores for the ARMOS subscale ranged between 27 and 85, with an alpha coefficient of .88. The scores for the AOS subscale ranged between 20 and 64, with an alpha coefficient of .86. Both scale scores appeared to have good internal consistency. The reliability of the subscales was consistent with Cuellar et al. [31] findings.

Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory (MASI) - The MASI is a 25-item measure developed to assess the sources of acculturative stress. The originally constructed scale created by Rodriguez N, eta l. [32], was developed to assess the acculturative stress among persons of Mexican origin living in the United States. This scale yielded four factors scales: Spanish Competency Pressures (the pressure to retain competency in their language of origin; seven items); English Competency Pressures (pressure to acquire competency in the host language; seven items); Pressures to Acculturate (pressure to acquire practices that are part of the dominant culture; seven items); and Pressures Against Acculturation (pressure to retain practices that are part of their culture of origin; four items). Spanish Competency Pressure items were modified to assess for Heritage Language Competency Pressure by changing the word Spanish to the general term heritage language (e.g., “I feel pressure to learn Spanish” was changed to “I feel pressure to learn my family’s heritage language”). The items are rated using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1: strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: neutral, 4: agree, 5: strongly agree). The items are summed with greater score indicating higher levels of acculturative stress.

Cronbach’s alpha for the MASI was 0.92 for Latinos, 0.91 for Asian Americans, 0.97 for men, 0.94 for women, 0.95 for U.S.-born, and 0.95 for foreign-born. For the total sample, alphas for Heritage Language Competency Pressure, English Competency Pressure, Pressure to Acculturate, and Pressure against Acculturation subscales were 0.86, 0.91, 0.84, and 0.81, respectively [33].

Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI II) - The BDI-II is a modified 1996 revision to the BDI created in 1961 by Aaron T. Beck measuring the severity of depression. The BDI-II includes 21 questions relating to symptoms of depression including hopelessness, irritability, feelings of guilt and being punished, as well as physical symptoms such as fatigue, weight loss, appetite change, and lack of interest in sex. Each answer is scored on a scale from 0 to 3 with higher total scores indicating more severe depression symptoms (0–9: minimal depression, 10–18: mild depression, 19–29: moderate depression, and 30–63: severe depression).

Validity and reliability of the BDI-II were psychometrically tested by Wang & Gorenstein [34], showing high reliability, and improved concurrent, content, and structural validity. The internal consistency was described as around 0.9 and the retest reliability ranged from 0.73 to 0.96. The correlation between BDI-II and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-I) was high and substantial overlap with measures of depression and anxiety was reported. The criterion-based validity showed good sensitivity and specificity for detecting depression in comparison to the adopted gold standard.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) - The BAI created by Aaron T. Beck [35], measures the severity of anxiety. The BAI includes 21 items asking about common symptoms of anxiety experienced within the past week including numbness and tingling, inability to relax, sweating, and fear of the worst happening. Each answer is scored on a scale from 0 to 3 (0: not at all, 1: mildly, 2: moderately, 3: severely), with higher total scores indicating more severe anxiety symptoms (0-7: minimal anxiety, 8-15: mild anxiety, 16- 25: moderate anxiety, and 26-63: severe anxiety). Validity and reliability of the BAI were psychometrically tested by Beck AT, e al. [34], showing high internal consistency and test-retest reliability. The internal consistency Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92 and the 1-week test-retest reliability was 0.75. The BAI was moderately correlated with the revised Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (.51), and mildly correlated with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (.25).

5.2.6. Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) - The AUDIT developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) is a 10- item screening tool assessing the amount and frequency of alcohol intake (questions 1-3), alcohol dependence (questions 4-6) and problems related to alcohol consumption (questions 7- 10) [36]. Questions 1 to 8 are scored on a five-point scale from 0 to 4, and questions 9 and 10 are scored on a three-point scale of 0, 2, and 4. The total scores range from 0 to 40. A total score of 8 or more is considered to indicate hazardous or harmful alcohol use (0-7: Low risk, 8-15: Risky or hazardous level, 16 or more: High risk). Several studies have measured the validity and reliability of the AUDIT 10. According to Selin [37], the correlation between the responses in the first and second application was somewhere between 0.6 and 0.8, except for item 9 that had a correlation of .29. Total score test retest reliability was .84. According to Dybek et al. [38], at the cutoff point of 8 or higher, 87.5% of subjects screened in the first test were also classified as positive in the retest, and 98.9% of those who scored below 8 in the first test were equally evaluated as negative in the second administration. In 10 studies evaluating the internal consistency, the mean value of Cronbach’s alpha was found to be .8, indicating high internal consistency. According to Saunders JB, et al. [39], using the cut-off point of 8, the overall sensitivity for hazardous and harmful alcohol use was 87% to 96%, with an overall value of 92%. AUDIT has been shown to be a simple method of early detection of hazardous and harmful alcohol use in a range of settings.

Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation-3 (BACE-3) - The BACE-3 was developed from items in existing scales including the BACE-2, systematic item reduction, and feedback from an expert group. It aimed to develop a comprehensive measure for assessing barriers to care-seeking for mental ill health, encompassing care avoidance post- as well as pre-contact with services [40]. The response categories ranged from 0 to 3 (0: not at all, 1: a little, 2: quite a lot: 3: a lot) with higher score indicating a greater barrier. For each barrier, three different scores may be given: the mean of the response scores, the percentage reporting they have experienced the barrier to any degree and the percentage experiencing the barrier as a major barrier [40]. The BACE-3 stigma-related barriers are items 3, 5, 8, 9, 12, 14, 17, 19, 21, 24, 26 and 28. The non-stigmarelated barriers may be classified, conceptually, into instrumental barriers (items 1, 6, 11, 15, 16, 27, 29, and 30) and attitudinal barriers (items 2, 4, 7, 10, 13, 18, 20, 22, 23, and 25).

5.2.8. Validity and reliability of the BACE were psychometrically tested by Clement et al. (2012). The BACE items were found to have acceptable test-retest reliability as all but one of the items exceeded the criterion for moderate agreement. The treatment stigma subscale had acceptable test-retest-reliability and good internal consistency. The subscale was significantly positively correlated with the Stigma Scale for Receiving Psychological Help (SSRPH) and the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) demonstrating convergent validity. The developmental process ensured content validity with the respondents giving the BACE a median rating of 8 on the 10-point quality scale [41].

Procedures

Data for this study was retrieved from participants through the Facebook social media website. The independent Facebook account, used only for the purposes of this study’s data collection, had an embedded link to Survey Monkey where participants could choose to participate in the study. This embedded link included the informed consent, the questionnaires, and the debriefing statement. Following the completion of the informed consent, the respondents were asked to complete a digital demographic questionnaire and the six surveys discussed above. The demographic questionnaire, ARSAA, MASI, BDI II, BAI, AUDIT, and BACE-3 questionnaires took approximately 20 to 25 minutes to complete, although there were individual differences in completion time. Respondents were asked for their voluntary participation in the study in the Facebook post. It was written in the post that their participation was voluntary and that the completion of the survey indicates their consent to participate in the study.

Each respondent was given a digital informed consent explaining the purpose and procedures of the study. In addition, all the information that was gathered was anonymous and no identifying information was obtained. All the information that was collected was kept on a password protected computer that only the researcher and the research Chairperson had access to. The data will be kept for three years and then subsequently destroyed. Upon completion of the surveys, each respondent received a digital debriefing statement with the researcher’s contact information and available resources, if need be. This debriefing statement was included as the final portion of the online survey in SurveyMonkey. Each respondent was also notified that their voluntary participation in this research study would lead to a $5 donation to the Armenia Fund, which supports large-scale, self-sustaining initiatives in both Armenia and Karabakh as a token of appreciation for their participation.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

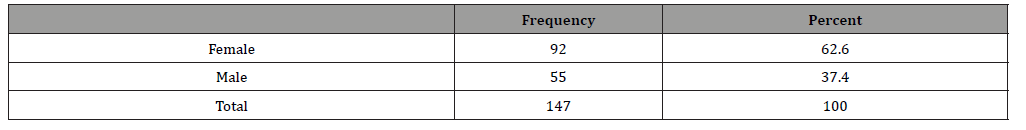

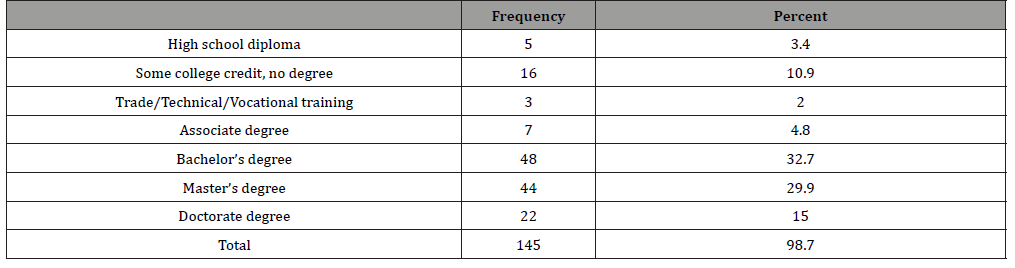

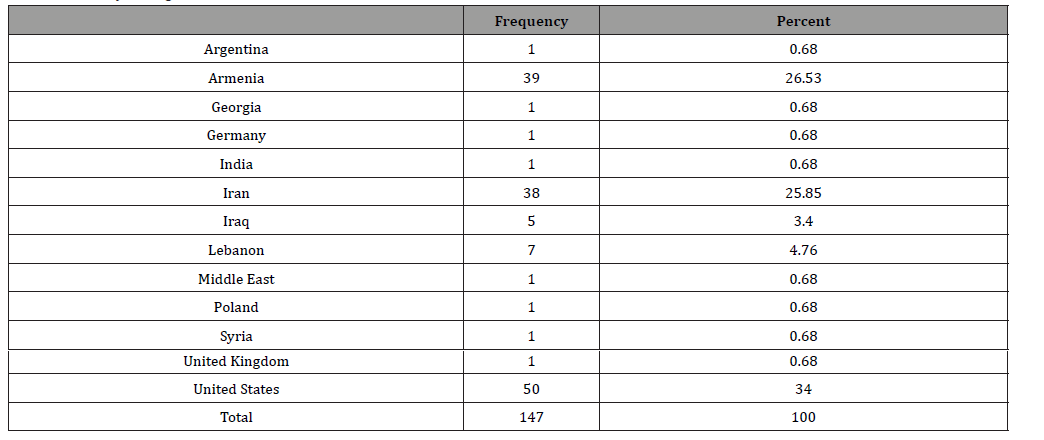

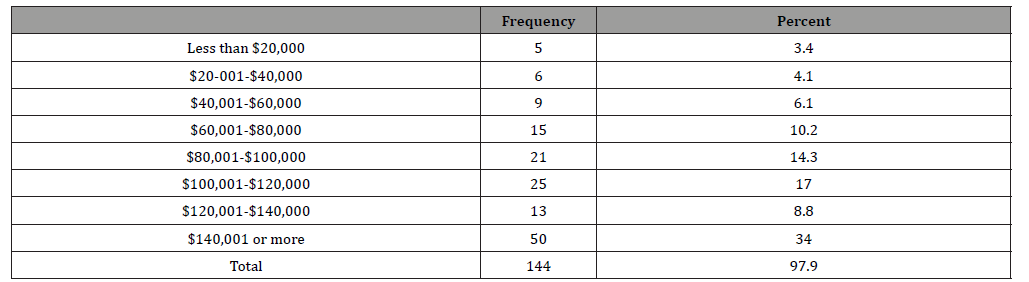

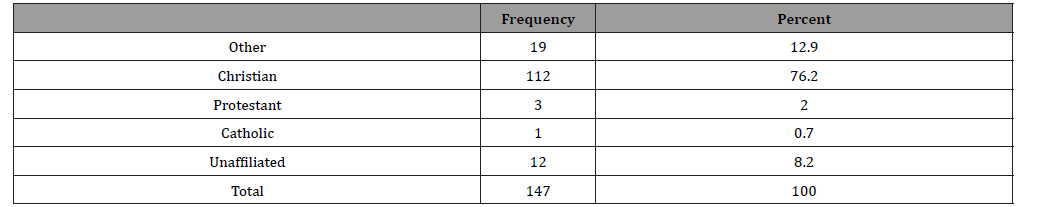

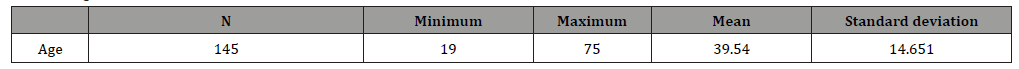

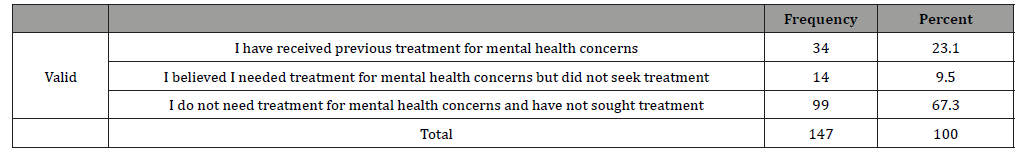

With regard to the sample’s demographic characteristics, 55 participants (or 37.4% of the sample) were male and 92 participants (or 62.6% of the sample) were female. The minimum and maximum ages of the participants were 19 and 75 respectively, with a mean of approximately 40. 34% of the sample reported having never lived in a country other than the United States for a substantial period of time. In addition, the length of U.S. residence ranged from 2 to 59 years, with a length of 26 to 30 years being the most common. 21.3% of the participants indicated that they have received previous treatment for mental health concerns, 9.5% indicated that they believed they needed treatment for mental health concerns but did not seek it, and 67.3% indicated that they did not need treatment and thus did not seek it. Of the participants that sought treatment, most of them received it from a mental health professional and/or a medical doctor. 76.2% of the participants identified themselves as Christian, while others identified as Protestant, Catholic, Unaffiliated, or Other. Additionally, 45.6% of the participants identified themselves as married or in a domestic partnership, while 42.2% identified as single or never married, and the rest identified as widowed, divorced, or separated. 77.6% of the participants earned a least a bachelor’s degree as their higher degree or level of school completed. The sample’s income level appeared to be quite high with approximately 59.8% of respondents reporting that their annual household income was greater than $100,000. While Armenian-American households have been shown to have higher median and average income levels than those of the nation in general [3], this factor could potentially erode the validity of the results obtained due to the influence of high socioeconomic status on various facets of psychological health and well-being.

Table 1:Gender Distribution.

Table 2:Education Level Distribution.

Table 3:Country of Origin Distribution.

Table 4:Household Income Distribution.

Table 5:Religious Preference Distribution.

Table 6:Marital Status Distribution.

Table 7:Age Distribution.

Table 8:Mental Health Treatment History.

Table 9:Level of Acculturation Scale.

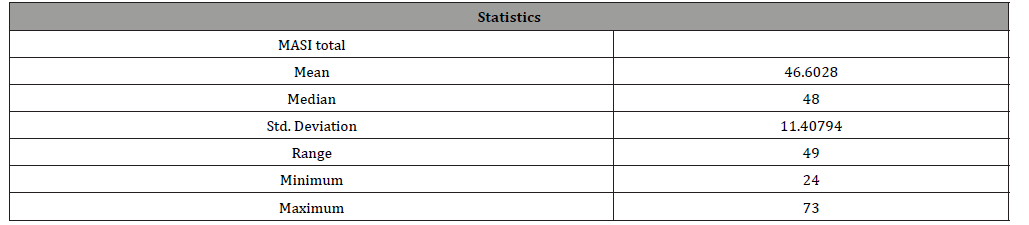

Table 10:Acculturative Stress Scale.

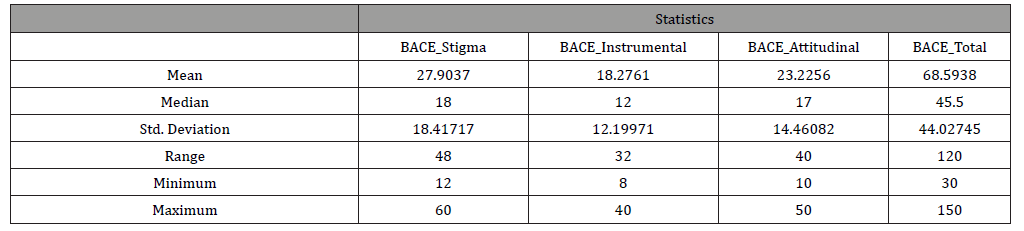

Table 11:Barriers to Treatment Scale.

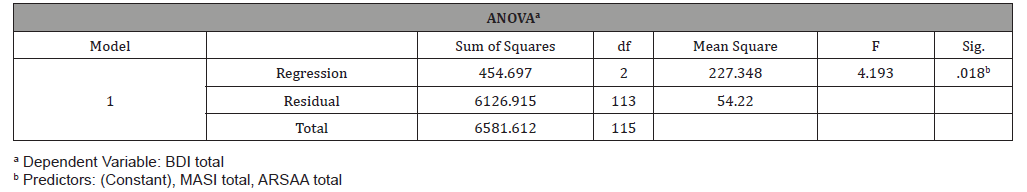

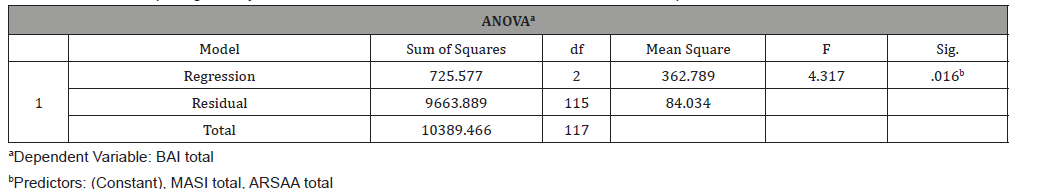

Table 12:ANOVA Exploring Depression Levels in Acculturative Stress and Level of Acculturation Groups.

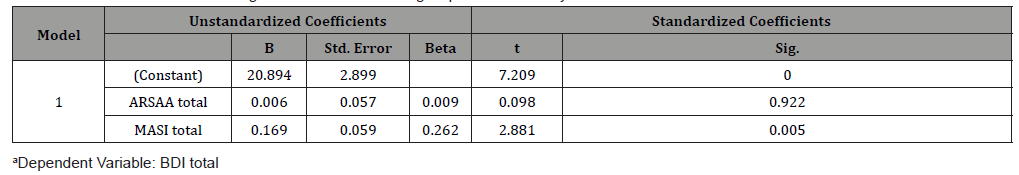

Table 13:Coefficients of Linear Regression Model Predicting Depression Level by Level of Acculturation and Acculturative Stress.

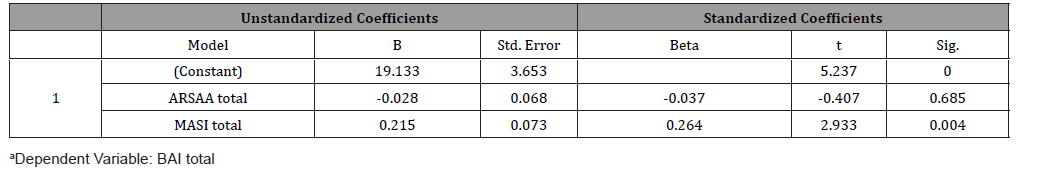

Table 14:ANOVA Exploring Anxiety Levels in Acculturative Stress and Level of Acculturation Groups.

Table 15:Coefficients of Linear Regression Model Predicting Anxiety Level by Level of Acculturation and Acculturative Stress.

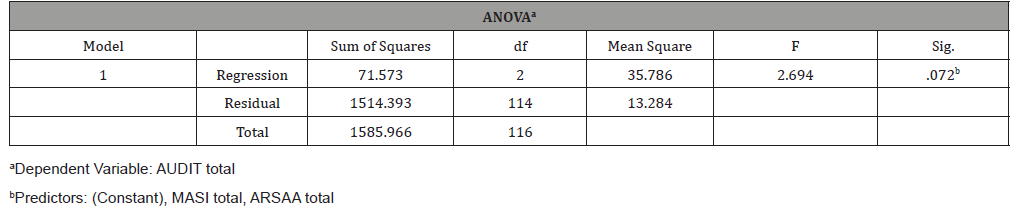

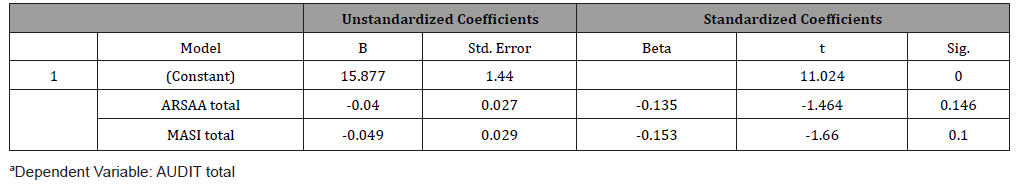

Table 16:ANOVA Exploring Alcohol Use Levels in Acculturative Stress and Level of Acculturation Group.

Table 17:Coefficients of Linear Regression Model Predicting Alcohol Use Level by Level of Acculturation and Acculturative Stress.

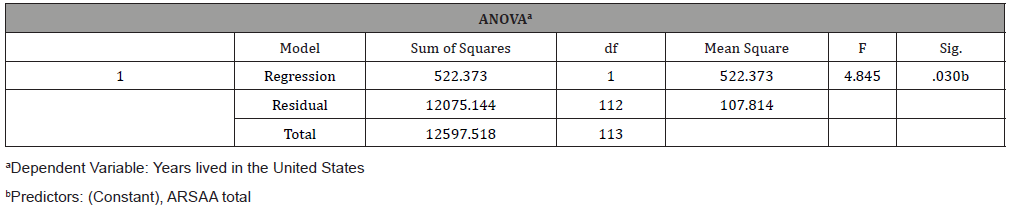

Table 18:ANOVA Exploring Years Lived in the United States in Level of Acculturation Groups.

Table 19:Coefficients of Linear Regression Model Predicting Years Lived in United States by Level of Acculturation.

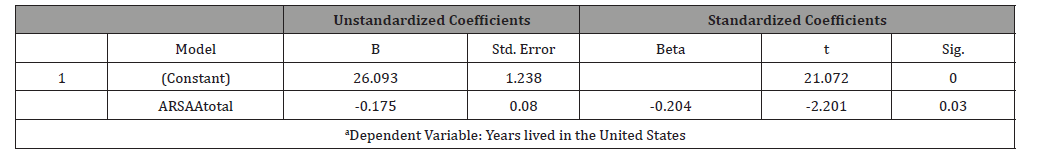

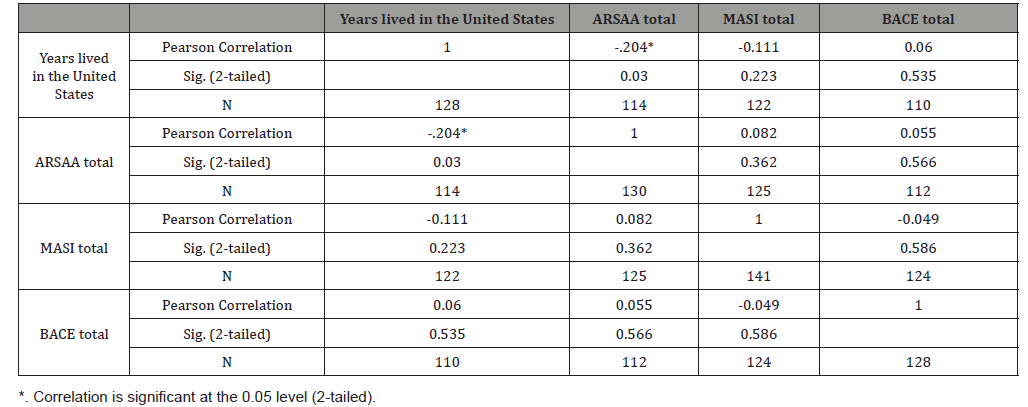

Table 20:Correlations Between Age, ARSAA, MASI, BACE, BDI, BAI, and AUDIT.

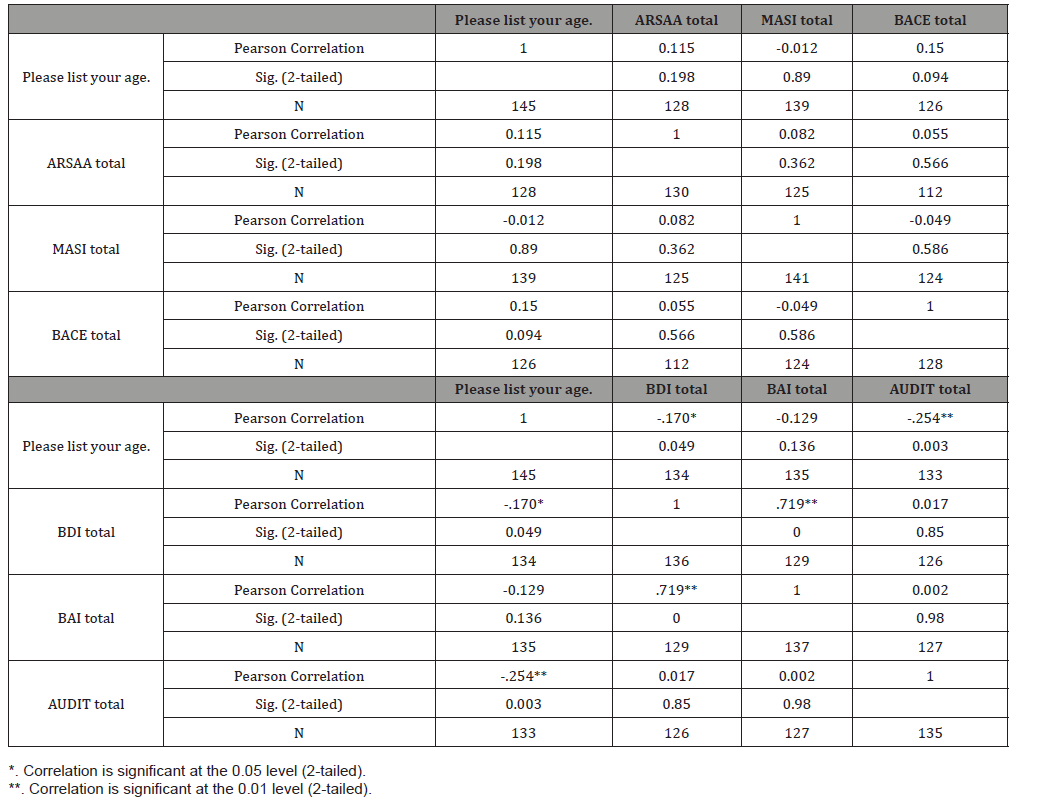

Table 21:Correlations Between Years Lived in the U.S., ARSAA, MASI, and BACE

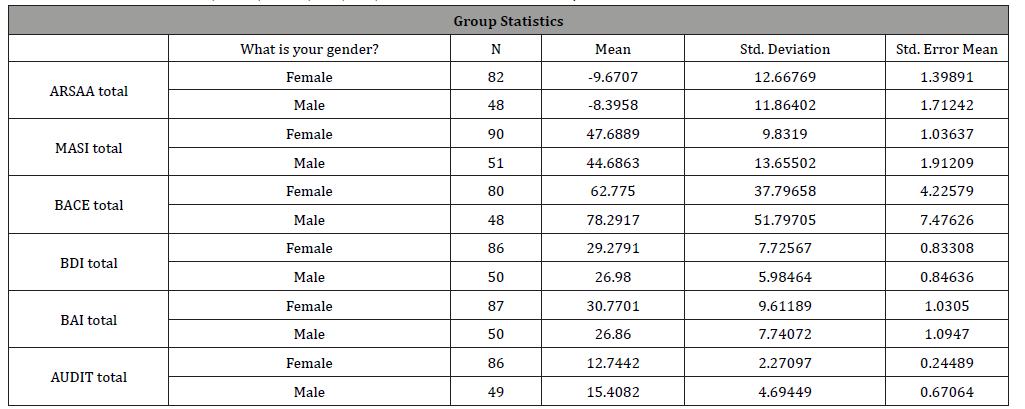

Table 22:Statistics of ARSAA, MASI, BACE, BDI, BAI, and AUDIT for Gender Groups.

Table 23:Independent Samples T-Test Examining Gender with ARSAA, MASI, BACE, BDI, BAI, and AUDIT.

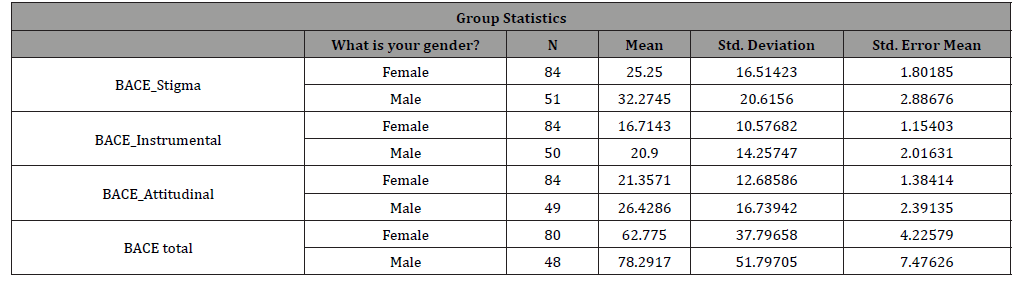

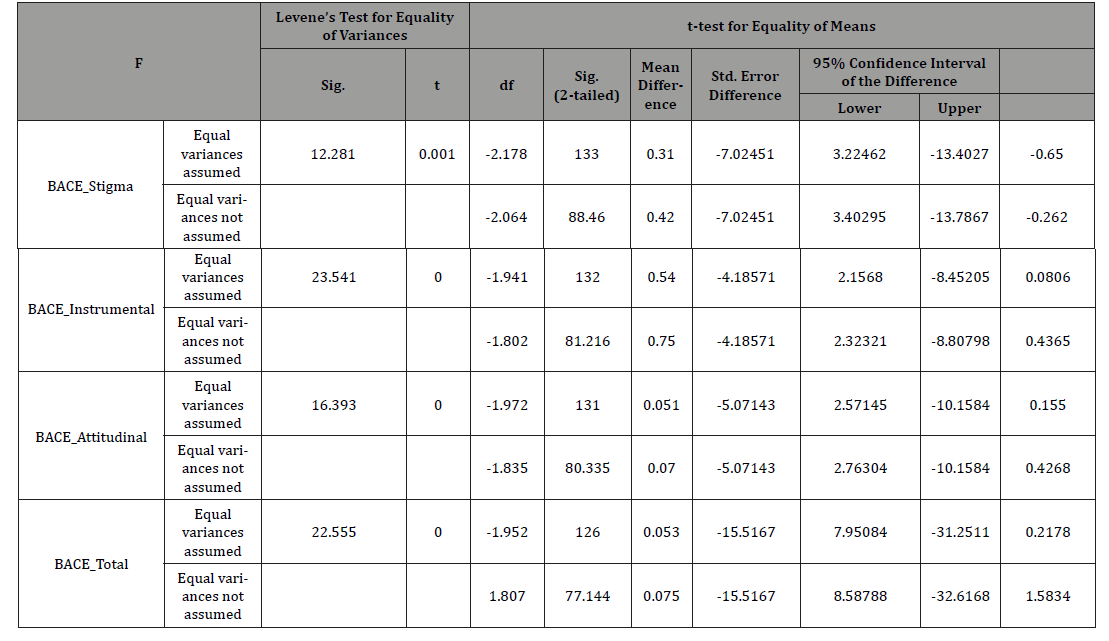

Table 24:Statistics of BACE Stigma, BACE Instrumental, and BACE Attitudinal for Gender Groups.

Table 25:Independent Samples T-Test Examining Gender with BACE Stigma, BACE Instrumental, and BACE Attitudinal.

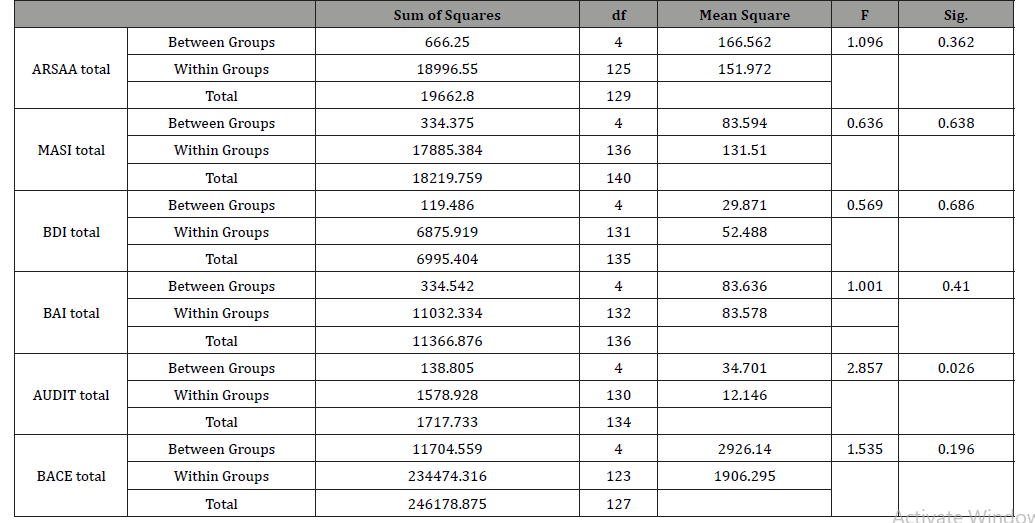

Table 26:ANOVA Predicting Marital Status.

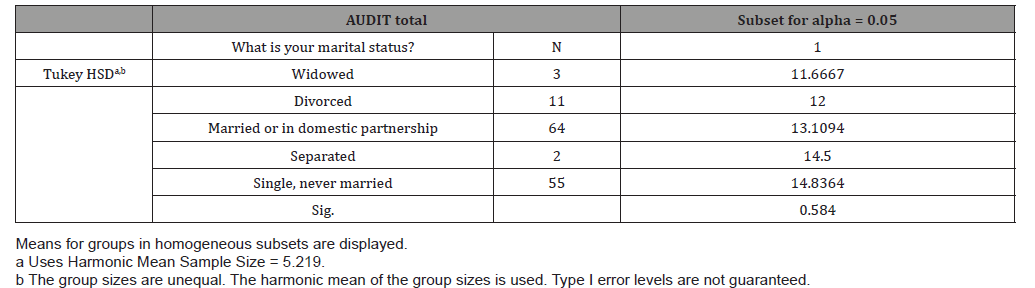

Table 27:Post-Hoc Test Comparing Alcohol Use Levels and Marital Status

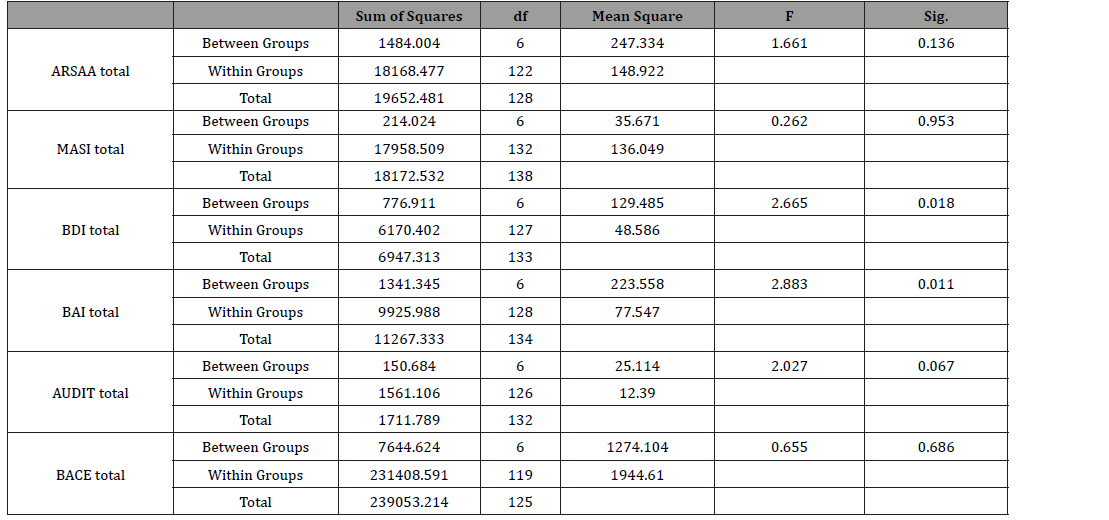

Table 28:ANOVA Predicting Education Levels.

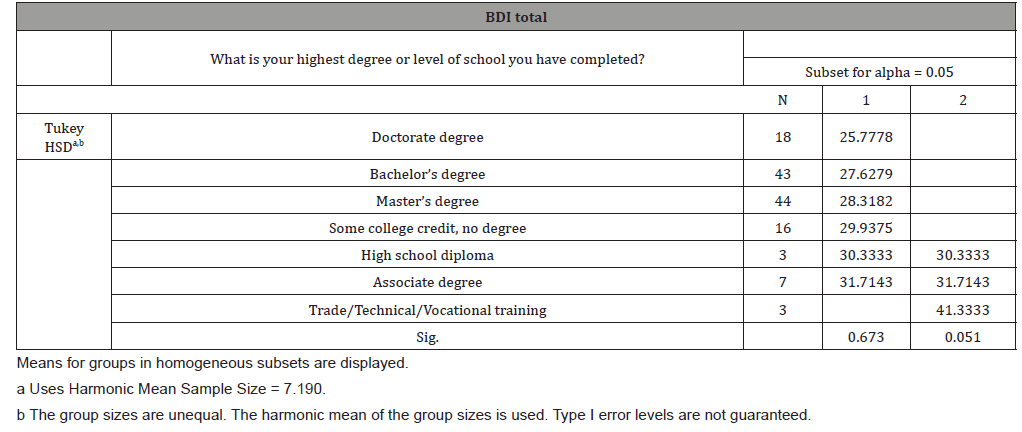

Table 29:Post-Hoc Test Comparing Depression Levels and Education Levels.

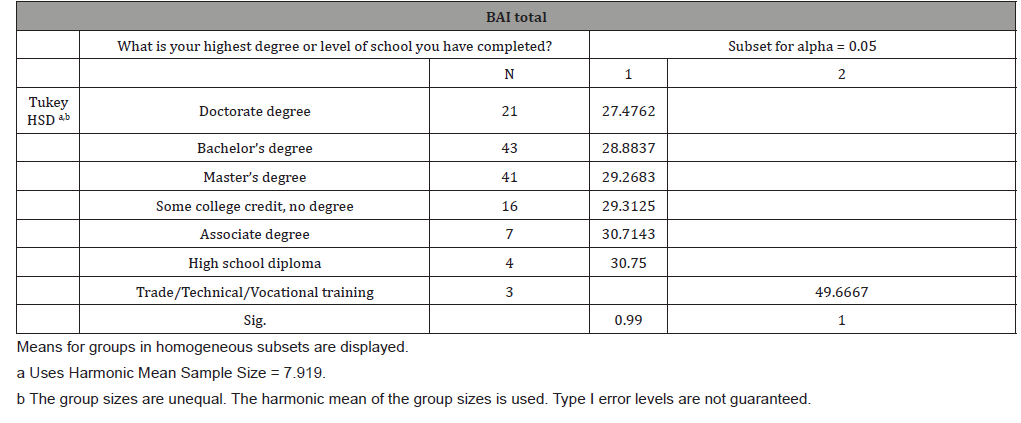

Table 30:Post-Hoc Test Comparing Anxiety Levels and Education Levels.

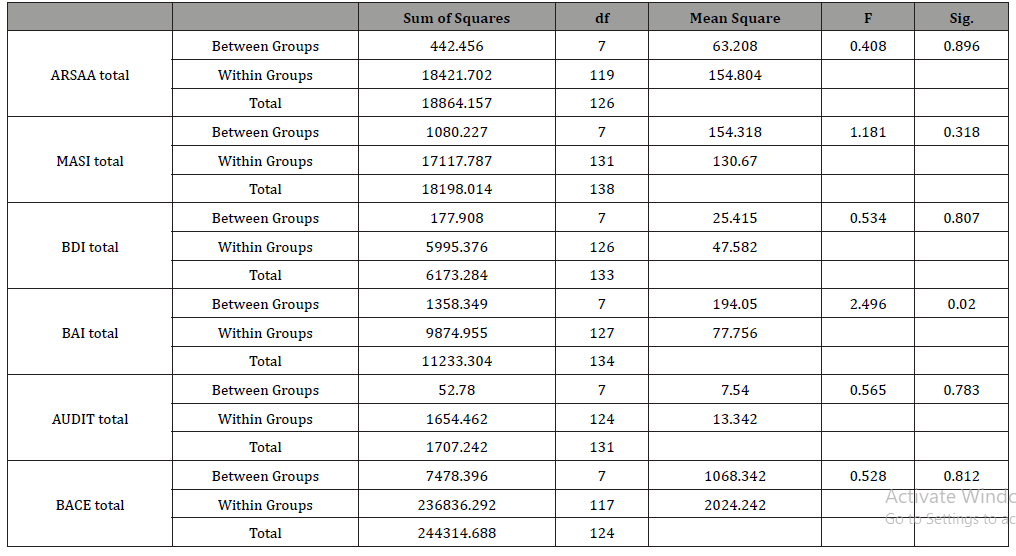

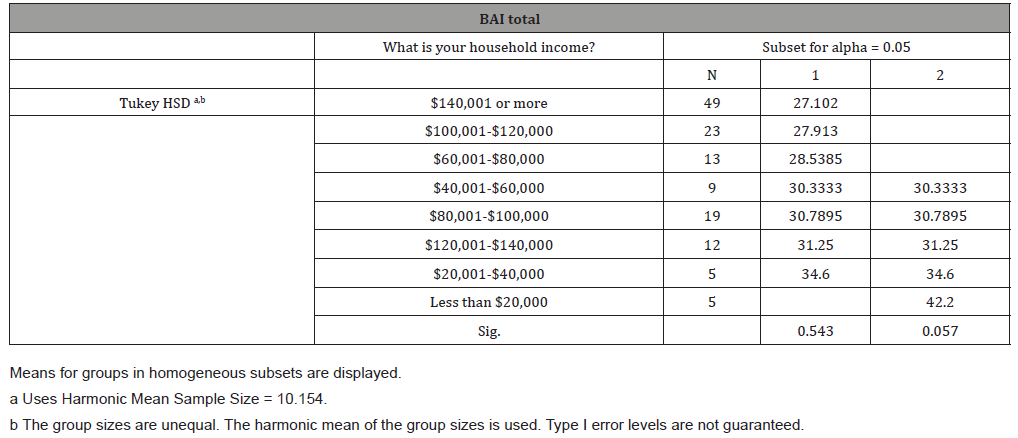

Table 31:ANOVA Predicting Household Income.

Table 32:Post-Hoc Test Comparing Anxiety Levels and Household Income

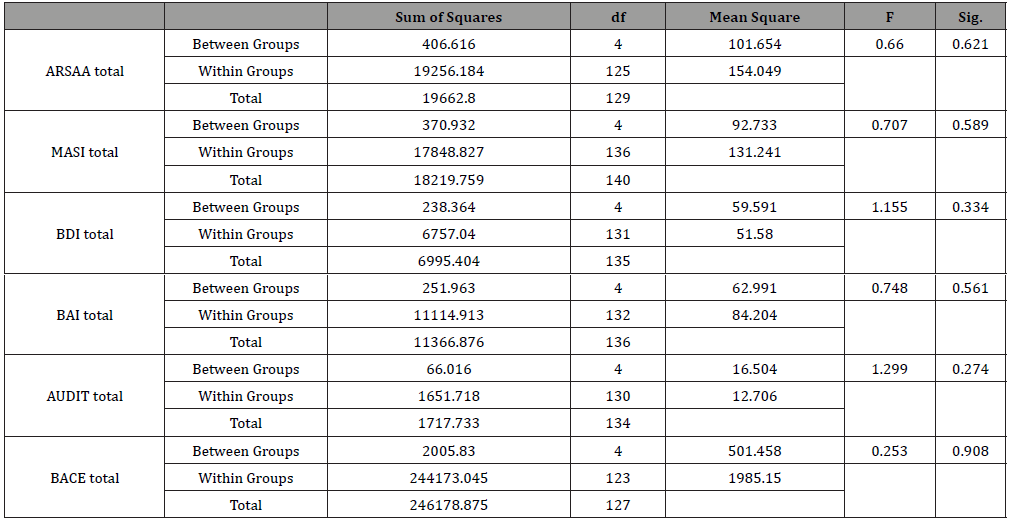

Table 33:ANOVA Predicting Religious Preference

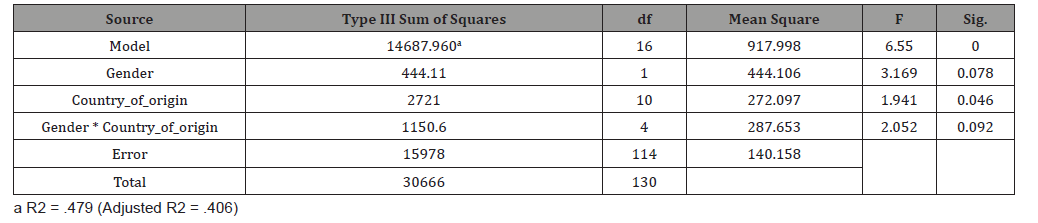

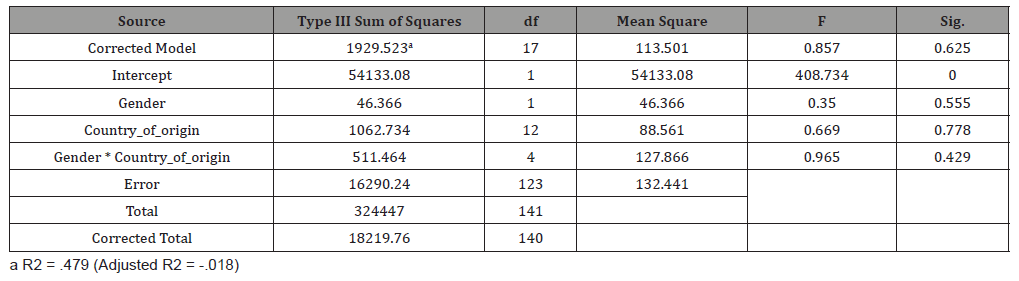

Table 34:ANOVA Exploring Gender and Country of Origin on ARSAA.

Table 35:ANOVA Exploring Gender and Country of Origin on MASI.

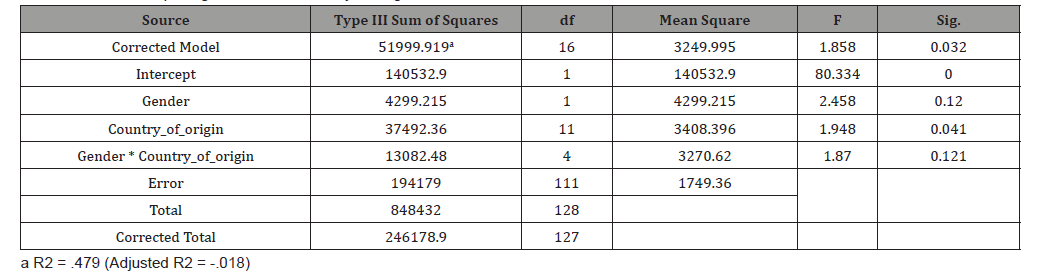

Table 36:ANOVA Exploring Gender and Country of Origin on BACE.

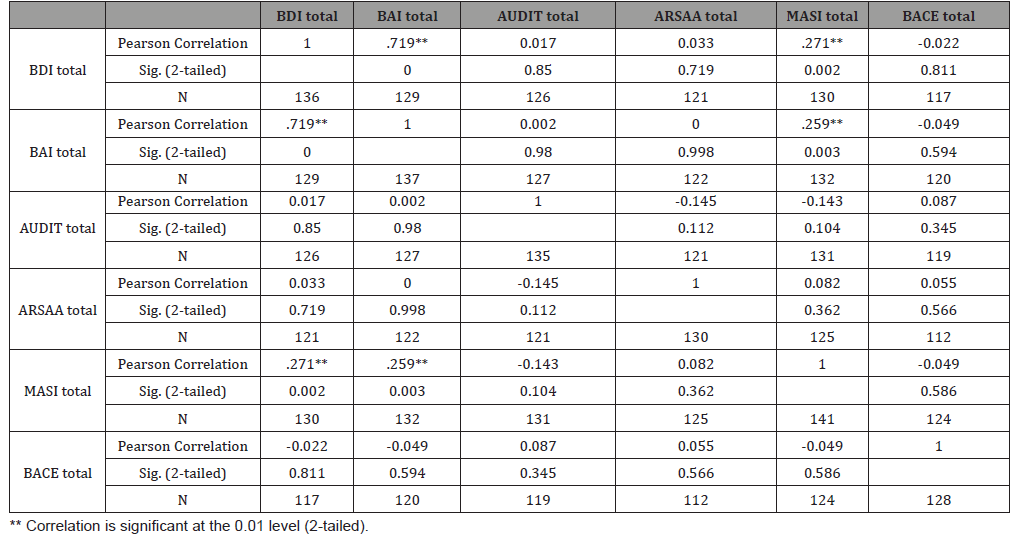

Table 37:Correlations Between ARSAA, MASI, BACE, BDI, BAI, and AUDIT.

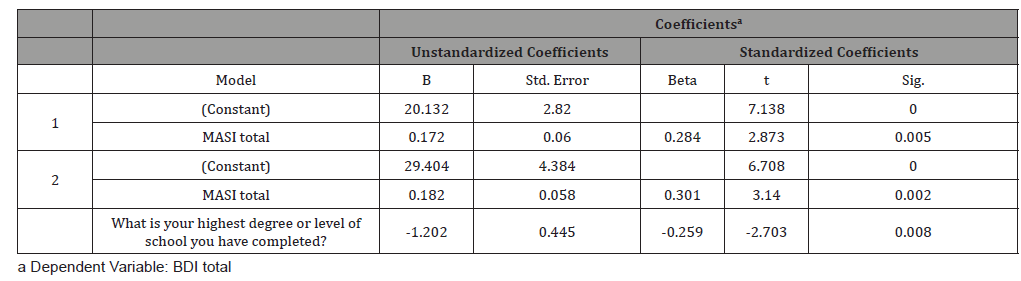

Table 38:Hierarchical Regression Predicting BD

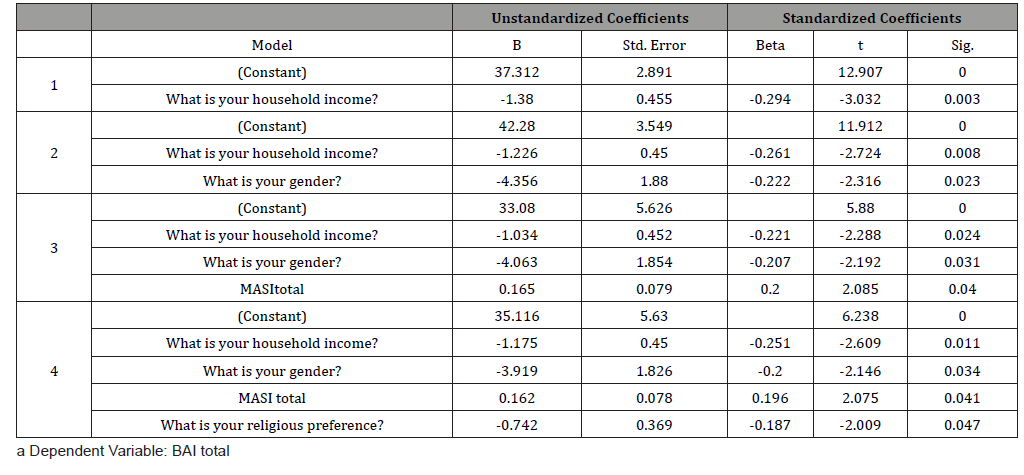

Table 39:Hierarchical Regression Predicting BAI

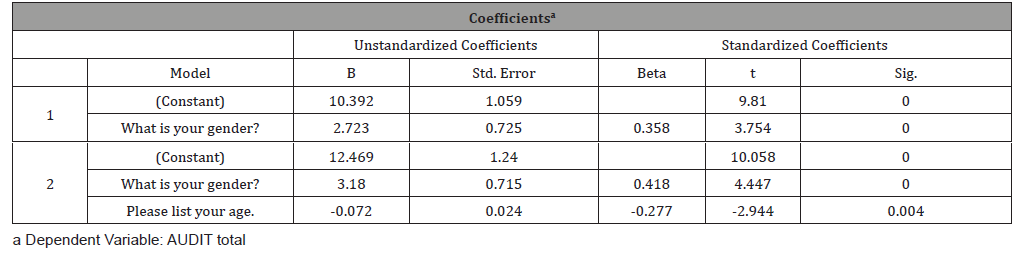

Table 40:Hierarchical Regression Predicting AUDIT.

Multiple Regression

A multiple regression analysis was conducted in order to ascertain whether level of acculturation (as subscales in the ARSAA) and acculturative stress (as subscale in the MASI) is predicted by depression level (in BDI). The regression model was found to be significant [F(2,113) = 4.193, p = 0.018, R2= 0.069]. The coefficients are provided in the table below. The MASI total scale was found to be a significant predictor, while the ARSAA total scale was not. Thus, higher levels of acculturative stress appeared to predict higher scores on the BDI and thus higher levels of depression.

A multiple regression analysis was also conducted in order to ascertain whether level of acculturation and acculturative stress is predicted by anxiety level (in BAI). The regression model was found to be significant [F(2,115) = 4.317, p = 0.016, R2 = 0.070]. The coefficients are provided in the table below. The MASI total scale was found to be a significant predictor, while the ARSAA total scale was not. Thus, higher levels of acculturative stress appeared to predict higher scores on the BAI and thus higher levels of anxiety. A multiple regression analysis was also conducted in order to ascertain whether level of acculturation and acculturative stress is predicted by alcohol use level (in AUDIT). The regression model was not found to be significant [F(2,114) = 2.694, p = 0.072, R2 = 0.045]. A multiple regression analysis was also conducted in order to ascertain whether level of acculturation is predicted by years lived in the United States. The regression model was found to be significant [F(1,112) = 4.845, p = 0.030, R2 = 0.041]. The coefficients are provided in the table below. The ARSAA total scale was found to be a significant predictor. Thus, lower levels of acculturation appeared to predict longer years lived in the United States.

Correlational Analysis

Correlational analysis (Pearson R) examining the relationship between the demographic variable of age and level of acculturation, acculturative stress, barriers to treatment, depression, anxiety, and alcohol use were conducted. There was no correlation between age and level of acculturation (rp = 0.115, p = n.s.), between age and acculturative stress (rp = -0.012, p = n.s.), between age and barriers to treatment (rp = 0.150, p = n.s.), and between age and anxiety level (rp = -0.129, p = n.s.). However, there was a negative correlation between age and depression level (rp = -0.170, p < 0.05, one sided), and a negative correlation between age and alcohol use (rp = -0.254, p < 0.01, one sided).

Correlational analysis (Pearson R) examining the relationship between years lived in the United States and level of acculturation, acculturative stress, and barriers to treatment were conducted. There was no correlation between years lived in the United States and acculturative stress (rp = -0.111, p = n.s.) and between years lived in the United States and barriers to treatment (rp = 0.060, p = n.s.). However, there was a negative correlation between years lived in the United States and level of acculturation (rp = -0.204, p < 0.05, one sided) such that as participants’ years lived in the United States increased, their level of acculturation decreased. Correlational analysis examining the relationship between the level of acculturation, acculturative stress, barriers to treatment on depression level, anxiety level, and alcohol use were also conducted. As expected, and explored in the regression analysis, there was a positive correlation between acculturative stress and anxiety level (rp = 0.259, p < 0.01, one sided) and a positive correlation between acculturative stress and depression level (rp = 0.271, p < 0.01, one sided).

Independent samples t-test

An independent samples t-test examining the relationship between the demographic variable of gender and level of acculturation, acculturative stress, barriers to treatment, depression level, anxiety level, and alcohol use were conducted. The test revealed differential patterns of anxiety level between genders (t(135) = 2.454, p = 0.015) such that females, on average, scored higher on the BAI than males; and revealed differential patterns of alcohol use level between genders (t(133) = -4.438, p = 0.000) such that males, on average, scored higher on the AUDIT than females. Additionally, the test revealed slightly differential patterns of barriers to treatment scores between genders (t(126) = -1.952, p = 0.053), such that males, on average, scored higher on the BACE than females. Furthermore, the test revealed no differential patterns of acculturation level between genders (t(128) = -0.567, p = 0.572), no differential patterns of acculturative stress between genders (t(139) = 1.509, p = 0.134), and no differential patterns of depression level between genders (t(134) = 1.811, p = 0.072).

An independent samples t-test examining the relationship between the demographic variable of gender and the three types of barriers to treatment were conducted. The test revealed differential patterns of stigma-related barriers between genders (t(133) = -2.178, p = 0.031) such that males, on average, scored higher on the BACE Stigma barriers scale than females. Additionally, the test revealed slightly differential patterns of non-stigma-related, instrumental barriers between genders (t(132) = -1.941, p = 0.054) such that males, on average, scored slightly higher on the BACE Instrumental barriers scale than females and slightly differential patterns of non-stigma related, attitudinal barriers between genders (t(131) = -1.972, p = 0.051) such that males, on average, scored slightly higher on the BACE Attitudinal barriers scale than females.

One-way ANOVA

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine if marital status groups differed in terms of their level of acculturation, acculturative stress, barriers to treatment, depression, anxiety, alcohol use, and barriers to treatment. The results suggested that there was only a significant difference between the marital status groups in terms of their alcohol use level (F(4,130) = 2.857, p = 0.026). Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test revealed that alcohol use increased from widowed participants to divorced participants to married participants to separated participants to single participants respectively.

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine if education level groups differed in terms of their level of acculturation, acculturative stress, depression, anxiety, alcohol use, and barriers to treatment. The results suggested that there were only significant differences between the education level groups in terms of their depression level (F(6,127) = 2.665, p = 0.018) and anxiety level (F(6,128) = 2.883, p = 0.011). Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test revealed that participants with high school diplomas or associate degrees as their highest degree of education, on average, scored higher on the BDI than their counterparts with college credits, master degrees, bachelor degrees, and doctoral degrees. Additionally, Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test revealed that anxiety level, on average, increased from participants with doctorate degrees to participants with bachelor degrees to participants with master’s degrees to participants with some college credit to participants with associate degrees to participants with high school diplomas respectively. A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine if household income groups differed in terms of their level of acculturation, acculturative stress, depression, anxiety, alcohol use, and barriers to treatment. The results suggested that there was only a significant difference between the household income groups in terms of their anxiety level (F(7,127) = 2.496, p = 0.020). Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test revealed that participants with household incomes of less than $20,000, on average, had higher anxiety levels than participants with incomes of $20,000-$60,000, $80,001-$100,000, or $120,001-$140,000, and those participants had higher anxiety levels than participants with incomes of $60,001-$80,000, 100,001-$120,000 and $140,001 or more. A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine if religious groups differed in terms of their level of acculturation, acculturative stress, depression, anxiety, alcohol use, and barriers to treatment. The results suggested that there are no differential levels of acculturation, acculturative stress, depression, anxiety, alcohol use, and barriers to treatment between the different religious groups.

Two-way ANOVA

A two-way ANOVA was conducted to explore the influence of gender and country of origin on level of acculturation. A main effect of country of origin was found (F(10,114) = 1.941, p = 0.046). There was no main effect of gender (F(1,114) = 3.169, n.s.) and no interaction between gender and country of origin (F(4,114) = 2.052, n.s.).

A two-way ANOVA was conducted to explore the influence of gender and country of origin on acculturative stress. There was no main effect of gender (F(1,123) = 0.350, n.s.), no main effect of country of origin (F(12,123) = 0.669, n.s.), and no interaction between gender and country of origin (F(4,123) = 0.965, n.s.).

A two-way ANOVA was conducted to explore the influence of gender and country of origin on barriers to treatment. A main effect of country of origin was found (F(11, 111) = 1.948, p = 0.041). There was no main effect of gender (F(1, 111) = 2.458, n.s.), and no interaction between gender and country of origin (F(4, 111) = 1.870, n.s.).

Hierarchical Regression

A hierarchical (stepwise) regression was conducted to determine if depression level was predicted by acculturation level, acculturative stress, barriers to treatment, gender, marital status, age, education level, religion, and household income. The best model only included level of acculturative stress and level of education as predictors (F(2, 93) = 8.059, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.148).

A hierarchical (stepwise) regression was conducted to determine if anxiety level was predicted by acculturation level, acculturative stress, barriers to treatment, gender, marital status, age, education level, religion and household income. The best model only included household income, gender, level of acculturative stress, and religion as predictors (F(4,94) = 6.128, p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.207). A hierarchical (stepwise) regression was conducted to determine if alcohol use level was predicted by acculturation level, acculturative stress, barriers to treatment, gender, marital status, age, education level, religion, and household income. The best model only included gender and age as predictors (F(2, 95) = 11.944, p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.201).

Discussion

As predicted, acculturative stress was found to be a significant predictor for depression and anxiety. A positive correlation between acculturative stress and depression level suggested that as participants’ acculturative stress increased, their depression levels increased. Similarly, a positive correlation between acculturative stress and anxiety level suggested that as participants’ acculturative stress increased, their anxiety levels increased as well. These findings are consistent with the literature that suggests that stressors of acculturation influence psychological well-being and development amongst other minority groups [41,42].

There are various coping styles, which include cognitive or behavioral efforts, that individuals can use to master, tolerate, reduce, or minimize stressful events. Coping can be identified as being either active or avoidant. Active coping involves an awareness of the stressor, followed by attempts to reduce the negative outcome, change the nature of the stressor itself, or how one thinks about it, while avoidant coping strategies involve ignoring the issue and often leads to activities or mental states that aid the denial of the problem [43]. Active coping is thought to mitigate the debilitating effects of stress, whereas avoidant coping is thought to be less effective [44].

Although acculturative stress was associated with higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms, active coping, which facilitated the person-environment interactions, was associated with better adjustment or lower depression whereas avoidant coping predicted poorer adjustment or higher levels of depression and anxiety [45]. Thus, it appears that parental support and active coping buffered the effects of acculturative stress on symptoms of depression and anxiety. Research has shown that adverse events can lead to various health problems, however life stress may have a lesser effect on individuals with more psychosocial resources. The stress-buffering model suggests that certain resources assist in helping reduce the impact of negative life events on one’s health. One such stressbuffering agent is social support or resources provided by others to help a person better cope with their problems. A generalized beneficial effect of social support could occur because large social networks provide persons with regular positive experiences and a set of stable, socially rewarded roles in the community [46]. It would be interesting to further assess Armenian American’s stressbuffering agents including their support systems and coping styles. With acculturative stress being an important and indicative factor of one’s psychological well-being, it is important to explore available buffers that could reduce the effects of acculturative stress and shield immigrants from psychological distress [45].

In this present study, acculturation level was not found to be a significant predictor of depression or anxiety. However, country of origin was found to be a significant factor in the participants’ acculturation level. This result suggested that a person’s country of origin may influence their cultural orientation, or the extent to which they acculturate and assimilate to a new culture and country. Furthermore, country of origin was found to be a significant factor in the participants’ barriers to treatment scale score. This suggested that one’s country of origin may influence their views on mental illness, which may consequently affect their views on seeking and receiving mental health treatment and services. Further analysis of the data showed that participants from the United States had the lowest levels of acculturation while participants from the Middle East had the highest levels of acculturation. Additionally, participants that lived in the United States the greatest number of years had the lowest levels of acculturation. These results suggest that individuals from the Middle East are more likely to assimilate to the American culture perhaps in hopes of fitting in with the mainstream culture. On the other hand, having been born and raised in the mainstream culture, participants from the United States may feel a need to retain their Armenian orientation. Being immersed in the American culture, individuals from the United States may be more likely to retain their Armenian culture in hopes of not forgetting their heritage and/or family’s culture and thus would consequently have lower levels of acculturation. For many Armenians, the personal stories and narratives of the Armenian Genocide and the struggles of the victims have been passed on from generation to generation. Often times, due to these stories, Armenian children grow up with a strong sense of unity and belonging to the culture [47]. Armenians are united in this ethnic community known as the Armenian diaspora [48]. It is likely that the desire for future Armenian generations to actively be part of the Armenian diaspora stems from the primary generation and their personal experiences with the genocide [2]. Future generations of Armenian-Americans have been told and retold the stories of their history and how their ancestors came to the United States, and they recognize that if it had not been for the Armenian genocide, they might not be where they are today [47]. Due to this, it may be that Armenian individuals from the diaspora including the United States are more likely to retain their Armenian orientation and thus have lower levels of acculturation.

In future studies, it is important to explore the possible impact of the participants’ immigration status on their level of acculturation and barriers to treatment. Research has shown that in Latino immigrants, citizenship status enhances civic engagement in American life, which includes individual and community level of involvement in social and political activities [49]. The uncertainty surrounding immigration policies and fears of deportation may obligate immigrants to quickly acculturate and assimilate into the dominant, American culture [50]. Legal status is also a major determinant of immigrants’ access to health services and may affect their seeking and utilization of mental health services. Thus, future studies should explore the effects of the participants’ citizenship status on their acculturation level and barriers to treatment in Armenian Americans. It is undeniable that some immigrants may experience racism, xenophobia, and anti-immigrant sentiments and that this discrimination may be a key cause of acculturative stress causing them to feel like they have to hide their ethnic identity [50]. In the aftermath of September 11th, there has been a heightened interest in the Middle East immigrant population living in the United States and an increased negative stigma against those individuals [51]. Exploring more about the differences in the acculturation process, and distinct challenges, of individuals that are born in the United States and born in a foreign country, including the Middle East, is warranted in future studies.

Various sociodemographic factors including age, gender, marital status, education level, and household income have consistently been identified as important factors in explaining the variability in depression rates. Taking all the demographic factors and variables into account, in the present study, depression level was only found to be predicted by acculturative stress and education level. As discussed, depression level was affected by acculturative stress such that the more acculturative stress the participant had, the more depressed they were. Additionally, depression level was affected by education level such that the lower education the participant had, the more depressed they were. Further analysis showed that participants with high school diplomas and associate degrees had higher depression scores than their college credits, master’s degrees, bachelor’s degrees, and doctoral degrees counterparts. Research has shown that socioeconomic deprivation including educational attainment has been implicated in higher psychological distress [52]. Longitudinal studies have shown that low educational levels were significantly associated with both anxiety and depression [53]. Thus, it appears that higher educational levels seemed to have a protective effect against such psychological issues in Armenian Americans.

Taking all the demographic factors and variables into account, in the present study, anxiety level was only found to be predicted by household income, gender, acculturative stress, and religious preference. As previously discussed, anxiety level was affected by acculturative stress such that the more acculturative stress the participant had, the more anxious they were. Further analysis suggested that participants with household income of less than $20,000 had the highest anxiety level out of all the income groups, followed by participants with household incomes of $20,000- $60,000, $80,001-$100,000, or $120,001-$140,000, followed by participants with household incomes of $60,001- $80,000, 100,001- $120,000 and $140,001 or more. This finding was, in part, consistent with the literature and researchers that found that individuals with a household income of less than $20,000 per year were at increased risk or several mental health disorders including anxiety disorders [54]. Surviving on $20,000 a year is likely to be very challenging and may be even more challenging for an individual depending on their household characteristics and circumstances. According to the Census Bureau and the poverty guidelines, for a household of 3, the 2018 threshold is $20,780 [55]. Although stress and anxiety associated with finances are particularly common, they are more serious among low- and moderate-income Americans [56]. Cross sectional study using nationally representative, individual level data from the Healthcare for Communities survey showed that the mental health inventory, indicating worse mental health, and the probability of anxiety or depressive disorder increased continuously from the highest to the lowest quintiles of family income [57]. It is undeniable that financial stressors, among others, may cause distress in various individuals and have adverse effects on their physical as well as mental well-being.

Acculturation level and acculturative stress were not found to be a significant predictor of alcohol use. However, alcohol use was predicted by a couple of sociodemographic variables including gender and age. The negative correlation found between age and alcohol use suggested that as the participants’ age increased, their alcohol usage decreased. Additionally, males, on average, had higher alcohol use levels than their female counterparts. Although gender did not significantly correlate with acculturation level and acculturative stress, gender did appear to play a significant part in anxiety, alcohol use, and barriers to treatment levels. The present study showed that females, on average, had higher anxiety levels than their male counterparts. When immigrating to mainstream American culture, Armenian women may experience additional stressors to conform to Western cultural norms and American specific gender roles. Thus, this finding suggested that the process of acculturation among Armenian American females may be exacerbating their already high levels of internalizing symptoms. From a young age, males and females are taught to deal with fear in two different ways: men are conditioned to tackle problems head-on, while women are taught to worry and ruminate as opposed to actively confronting their challenges [58]. “From a socialization angle, there’s quite a lot of evidence that little girls who exhibit shyness or anxiety are reinforced for it, whereas little boys who exhibit that behavior might even be punished for it” [58]. Although these may be generalizations, they give a glimpse into how differences in upbringing may contribute to the gender gap in anxiety. Additionally, women may be getting diagnosed with anxiety disorders twice as often as men because men are much less likely to seek psychological help and thus consequently less likely to get diagnosed. As seen in the present study, this gender gap in anxiety also appears to be prominent in the Armenian American population.

In the present study, females, on average, had lower alcohol use levels than their male counterparts. The differences in cultural standard and gender normative behaviors in the Armenian culture may explain these results. In modern Armenia, especially among men, there is a deep toasting culture at family and social gatherings. Armenians highly appreciate the culture of consuming traditional drinks, including their famous Armenian Cognac and Artsakh Vodka. Large general-population surveys of men’s and women’s drinking behaviors in 35 countries over a 10-year period has shown that men still exceed women in drinking and high-volume drinking, although gender ratios differ in various countries [59]. As seen in this study, it appears that these alcohol drinking patterns are no different in Armenian American males and females.

In the present study, males expressed more BACE stigmarelated barriers including concerns about being seen as weak, crazy, or a bad parent as well as concerns about what their family and friends might think, say, or do. Additionally, males had slightly higher BACE non-stigma-related barriers (both instrumental and attitudinal barriers) including being unsure where to get help, wanting to solve their problem on their own, thinking that the problem will get better without help, not wanting to talk about their feelings and emotions, or preferring to get alternative forms of care. It is undeniable that the stigma associated with mental health in the Armenian community contributes to inadequate care and barriers to receiving treatment. Numerous women recounted being “forcibly sent to psychiatric hospitals by family members for simply having problems with their brother” [60]. Under Armenian law, one phone call to the police or psychiatric institution claiming that someone is suicidal or homicidal is enough to have them hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital [60]. Thus, Armenian individuals may be hesitant to disclose their issues in fears of being locked up. This mental health stigma is likely to be higher in Armenian males as a result of the patriarchal and male dominated culture. Often times, Armenian men are the head of the household and the family breadwinner. They are portrayed as strong and have the authority in the household. Admitting that they may have psychological symptoms and/or a mental illness poses too much risk and thus Armenian males are likely to minimize their issues and problems. This finding was consistent with the previous literature, which shows that men are less likely to seek mental health services and therapy. As explored in this study, mental health stigma is still very much alive in the Armenian community. It is imperative to educate the Armenian community about mental illness and attempt to put an end to life-limiting mental health stigma and discrimination.

In the present study, age played a role in depression and alcohol use levels. The negative correlation between age and depression levels suggested that as the participants’ age increased, their depression level decreased. Similarly, the negative correlation between age and alcohol use levels suggested that as the participants’ age increased, their alcohol use decreased. This study findings suggested that the young adults may be feeling more depressed than their older counterparts. According to the American Psychological Association, 35% of polled adults reported feeling more stress this year compared to last year, and 53% reported that they received little or no support from their health care providers in coping with that heightened stress [61]. Millennials, or those aged 18 to 33, are growing up at a tough time with a lot of high expectations for what they should be and should achieve [62]. These daily stressors are likely to interplay with their psychological well-being and may increase their depression symptoms. According to the 2016 American College Health Survey, 17% of surveyed university students felt so depressed that it was difficult to function and 19% felt overwhelmed by all they had to do [63].

Furthermore, marital status played a role in alcohol use levels. This study showed that single participants had the highest alcohol use levels, with levels decreasing to separated participants, married participants, divorced participants, and widowed participants correspondingly. This study finding was consistent with the previous literature, which suggests that marriage serves as a protective factor against alcohol abuse. Studies have shown that individuals who are married or cohabiting generally tend to drink less and less frequently than their single counterparts who drink more often and in larger quantities [64]. Additionally, once the relationship or marriage is over, people may be more likely to slip into alcohol abuse [64]. However, these trends may depend on the nature of the intimate relationship and thus may be the reason why it did not hold true for divorced and widowed participants in the present study.

Significant differences between the different education levels groups were found in terms of their depression and anxiety levels. Participants with high school diplomas or associate degrees as their highest degree of education, on average, had higher depression levels than their counterparts with college credits, master degrees, bachelor degrees, and/or doctoral degrees. Similarly, participants with high school diplomas had the highest anxiety levels when compared with their other counterparts. Anxiety level increased from participants with high school diplomas to participants with associate degrees to participants with some college credit to participants with master degrees to participants with bachelor degrees to participants with doctorate degrees. This study findings were consistent with the literature and longitudinal analysis that shows that low educational levels, and low socioeconomic status, are significantly associated with both depression and anxiety [55]. Individuals with higher education, and thus higher incomes, are often spared the health-harming stresses that accompany social and economic hardship, while individuals with less education may have fewer resources including social support and sense of control to buffer the effects of stress [65]. Educated individuals tend to have larger social networks, which bring access to financial, psychological, and emotional resources and may help them to reduce hardship and stress [66]. Additionally, education in school and other learning opportunities build skills and foster traits that are important in life from cognitive skills to problem solving and fostering key personality traits, which may be important to health and psychological well-being [67]. Greater personal control may also lead to healthier behaviors and thus those with greater perceived personal control may be more likely to initiate preventive behaviors [67].

Clinical Implications

The clinical implications of the present study could entail improved quality of life and diminished rates of mental health symptoms and disorders for Armenian Americans who experience less acculturative stress. Acculturative stress refers to the feeling of tension and anxiety that accompany efforts to adapt to the orientation and values of the dominant culture [68]. According to Miller et al. [69], acculturative stress was a significant factor in predicting mental health difficulties in Asian Americans. Those experiencing high levels of acculturative stress were more likely to experience major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder as compared to those experiencing relatively low levels of stress [67]. Additionally, in Latino Americans, acculturative stress was directly related to psychological adjustment and distress [70] and in Arab Americans, acculturative stress predicted psychological problems [71]. Furthermore, according to Papazyan A, et al. [72], Armenian-American women with lower levels of acculturative stress exhibited greater life satisfaction than those women with higher levels of acculturative stress. The present study extended the literature by exploring the effects of acculturative stress in both Armenian males and females. Acculturative stress was found to be a significant predictor for both depression and anxiety levels and thus had a direct impact on their psychological functioning. The stress associated with the acculturation process may be partially due to the tension and concerns of sustaining their ethnic identity and affiliation with their ethnic community, while adjusting and adapting to the new and different cultural norms and behavioral expectations [72]. Similar to other minority groups, it appears that acculturative stress challenged the Armenian population through exposure to societal values, cultural norms, and language preference, amongst others. Considering these results, it may be inferred that higher levels of acculturative stress could increase the probability that an individual will develop mental health concerns and psychological distress. Based on this information, clinicians should consider how to assess Armenian Americans’ acculturation level and related stressors as well as ways in which these experiences may affect their mental health. Additionally, clinicians are likely to benefit from considering the importance of acculturation and its associated stressors when working with this population. It may be valuable for clinicians to administer the Multidimensional Acculturation Stress Inventory (MASI) when working with Armenian American individuals to assess the specific acculturative stressors that are causing them concern and psychological distress. This strongly advocates for clinicians’ incorporation of cultural values and factors into therapy and mental health treatment. The clinician should not impose their values, beliefs, and/or expectations onto their client but rather allow the client to be the “teacher” and explain how they, their family, and their culture functions. The clinician may ask questions that promote comfort, validate their experiences, and respect their cultural beliefs and values. The clinician should show genuine and honest curiosity for the client’s individual and unique experiences and interest in understanding more about their acculturation journey and history. Due to the historical and cultural factors of the Armenian people, these individuals may have some cultural paranoia or cultural mistrust of foreigners. It may take an Armenian individual a considerably longer amount of time to feel comfortable with a therapist in the therapy sessions. A major element in addressing this mistrust in psychotherapy is to acknowledge this reality with them and explore the reasons for this mistrust to avoid negative views and expectations of the therapist and possible premature termination [75]. Thus, the clinician should keep in mind that building trust and rapport are key components when working with these individuals. Interventions with these Armenian American individuals may seek to enhance available social support or strengthen close family relationships and teach to use active coping skills when exposed to high levels of acculturative stress. This is likely to make the individuals less vulnerable to negative events, enhance their psychological adjustment, and improve their mental health and well-being.

The present study found that Armenian Americans have various stigma and non-stigma related barriers to seeking mental health treatment. It may be valuable for clinicians to administer the Barriers to Accessing Care (BACE) scale when working with Armenian American individuals to assess the barriers most prominent to them. Additionally, since in the present study, country of origin was found to be a significant factor in the participants’ barriers to treatment scale score, it is important to explore more about their views on seeking and receiving mental health treatment and services. In therapy, it is likely that Armenian Americans clients may initially downgrade their symptoms or “psychological distress” as a way to “save face” or to prevent a negative reflection upon themselves and/or their families. Learning more about these barriers to treatment would allow clinicians to provide culturally appropriate outreach and mental health education to this underserved population.

Limitations

A major limitation to this study was that the measured variables were highly vulnerable to desirable responding. Unfortunately, there are a few reasons why self-report questions may not be entirely valid. For one, with self-report measures, the researcher relies on the honesty of the participants. Possible dishonesty on the measures in this study may alter the results and consequently affect its conclusions. The degree to which participants are dishonest will undoubtedly vary with the topic of the questions and may include questions about their mental health and/or alcohol use. In addition, the participant may lack the introspective ability to provide an accurate response to an asked question despite their willingness to be honest or may vary regarding their understanding or interpretation of the particular questions.

Another limitation to this study is that the sample was collected using convenient and snowball sampling techniques used. This type of sampling is likely to not be representative of the general population and thus the results may not be generalizable to other settings. Random sampling would eliminate this bias and would likely be representative of the general Armenian immigrant population. Unfortunately, this type of sampling is difficult for the scope of this study. Additionally, another further limitation to the sample of this study was that it was examining individuals of Armenian descent in only one geographic location, Los Angeles County. Examining only the Armenians living in Los Angeles may be a threat to external validity as it may not be representative of Armenians in other states or countries around the world. The acculturative stress may differ by geographic location and thus this may consequently affect the immigrant’s level of acculturation. Looking at Armenians in various states of the United States would ensure representative results of the general Armenian population. Unfortunately, this is beyond the scope of this study, although it should be further assessed. Armenians in the Los Angeles metropolitan area may have a story of their own. A small part of Los Angeles has officially been named “Little Armenia,” pointing to the significant population of Armenians living in that area. The city and its entrepreneurial immigrants accommodate Glendale’s largest minority population and encourage the continued gathering of Armenian settlers from around the world [62]. Taking this into account, it is possible that the dynamics of the city itself affects the Armenians living there and consequently their acculturation process. Thus, this study had an inclusion criterion for the participants to live in Los Angeles County to be able to explore the characteristics of Armenians in this specific County. Additionally, another inclusion criterion was for the participant to be fluent in the English language. This is a limitation as using only English-speaking participants may skew the sample in regard to their acculturation level. Thus, unfortunately due to this language barrier, this study may be unable to assess all Armenians.

Acknowledgements

First, I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to my family. Through the trials and struggles of life, you have constantly encouraged me and believed in me at times when I did not believe in myself. This research article, and my doctoral degree, stands as a testament to your unconditional love and support. They would not have been possible without you. I cannot thank you enough! Second, I would like to thank my wonderful husband for his unfailing support and understanding throughout my years of study. You were always around in times of frustration and have been tolerant and patient throughout it all. Last but not the least, I would like to offer my gratitude to my dissertation chair, Dr. Tica Lopez and my committee member, Dr. Anindita Ganguly for their patient guidance throughout this extensive research process.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- National Statistical Service of the Republic of Armenia (2015) Statistical yearbook of Armenia population.

- Watenpaugh KD (2013) Are there any children for sale? Genocide and the transfer of Armenian children (1915–1922). Journal of Human Rights 12(3): 283-295.

- US Census Bureau (2011) American community survey 1-year estimates.

- Barsoumian N (2011) WikiLeaks: U.S. ambassadors “decipher.”

- Mody R (2007) Preventive healthcare in children. Immigrant Medicine Pp. 515-535.

- Miller AM, Wang E, Szalacha L, Sorokin O (2009) Longitudinal changes in acculturation for immigrant women from the former Soviet Union. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 40(3): 400-415.

- Sher L (2010) A model of suicidal behavior among depressed immigrants. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 10(1): 5-7.

- McLean D, Goldstein M, McGlinchy L (2006) A selective literature review: Immigration, acculturation, & substance abuse. Newton, MA: Education Development Center.

- Boyer P (2001) Cultural assimilation. International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 3032-3035). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Takooshian H (2007) Armenian immigration to the United States today from the middle east. Journal of Armenian Studies 3: 133-155.

- Allen M, Elliott M, Kataoka S, Morales L, Hambarsoomian K, et al. (2007) The contribution of family and acculturation-related stress to Latino adolescents’ mental health: A social network approach. Journal of Adolescent Health 40(2): S19-S54.

- Cervantes RC, Padilla AM, Napper LE, Goldbach JT (2013) Acculturation-related stress and mental health outcomes among three generations of Hispanic adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 35(4): 451-468.

- Hwang W, Ting JY (2008) Disaggregating the effects of acculturation and acculturative stress on the mental health of Asian Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 14(2): 147-154.

- Huang C (2006) Acculturation, Asian cultural values, family conflict, and perceived stress in Chinese immigrant female college students in the United States. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: Sciences and Engineering, 67(6): 3453.

- Suinn RM (2010) Reviewing acculturation and Asian Americans: How acculturation affects health, adjustment, school achievement, and counseling. Asian American Journal of Psychology 1(1): 5-17.

- Kramer E, Ton H, Lu F (2008) Saving face: Recognizing and managing the stigma of mental illness in Asian Americans.

- Wu FH (2002) Yellow: Race in America beyond black and white. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Dichoso (2010) Stigma haunts mentally ill Latinos.

- Rastogi M, Massey Hastings N, Wieling E (2012) Barriers to seeking mental health services in the Latino/a community: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Systemic Therapies 31(4): 1-17.

- Jang Y, Chiriboga DA, Herrera JR, Tyson DM, Schonfeld L (2009) Attitudes toward mental health services in Hispanic older adults: The role of misconceptions and personal beliefs. Community Mental Health Journal 47(2): 164-170.

- Shattell MM, Hamilton D, Starr SS, Jenkins CJ, Hinderliter NA (2008) Mental health service needs of a Latino population: A community-based participatory project. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 29(4): 351-370.

- Guendelman S, Wagner TH (2000) Health services utilization among Latinos and white non-Latinos: Results from a national survey. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 11(2): 179-194.

- Spencer M, Chen J, Gee G, Fabian C, Takeuchi D (2010) Discrimination and mental health-related service use in a national study of Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health 100(12): 2410-2417.

- Van Baelen L, Avetisyan T (2004) Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour towards mental healthproblems in Tchambarak and Gavar. Yerevan: Médecins Sans Frontiè

- Van Baelen L, Theocharopoulos Y, Hargreaves S (2005) Mental health problems in Armenia: Lowdemand, high needs. The British Journalof General Practice 55(510): 64-65.

- Usmani S (2014) Access to mental health care in the Middle East: What are the barriers?

- Young JL (2015) Untreated mental illness.

- Bussing Birks M (n.d.) Mental illness and substance abuse.

- Harris KM, Udry JR, (2015) National longitudinal study of adolescent to adult health (Add Health), 1994-2008. Retrieved from Data Sharing for Demographic Research (ICPSR 21600).

- Cuellar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R (1995) Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 17: 275-304.

- Ayvazian A (2008) Relationship between opinions about mental illness, help seeking behaviors and acculturation among Armenian American women. Retrieved from American Journal of Contemporary Research (2162-142X).

- Rodriguez N, Myers HF, Mira CB, Flores T, Garcia Hernandez L (2002) Development of the multidimensional acculturative stress inventory for adults of Mexican origin. Psychological Assessment 14: 451-461.

- Castillo LG, Cano MA, Yoon M, Jung E, Brown EJ, et al. (2015) Factor structure and factorial invariance of the multidimensional acculturative stress inventory. Psychological Assessment 27(3): 915-924.

- Wang YP, Gorenstein C (2013) Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A comprehensive review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatri 35(4): 416-431.

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA (1988) An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 56(6): 893-897.

- Shevlin M, Smith GW (2007) The factor structure and concurrent validity of the alcohol use disorder identification test based on a nationally representative UK sample. Alcohol & Alcoholism 42: 582-587.