Research Article

Research Article

Aberrant Prescription Medication Seeking Behavior Used by Prescription Drug Users to Obtain Prescription Medications from Physicians: A Qualitative Review of Webpages, Blogs and Forums

Siavash Jafari*, Ashkan Nasr and Nazila Hassanabadi

Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Canada

Siavash Jafari, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Canada.

Received Date: November 05, 2019; Published Date: December 10, 2019

Abstract

Background: Non-medical use of prescription medications is a public health concern. Individuals who suffer from substance dependence utilize a variety of aberrant behaviors to obtain prescription medications. They share their methods and experiences with others in social media and online platforms and educate each other on how to manipulate the providers, so that they can successfully obtain their medications of choice.

Objectives: The main objective of this qualitative study was to review the content of webpages, blogs, and forums to explore the most common approaches shared by individuals with prescription medication dependence to obtain such medications.

Methods: We used a combination of keywords to search five main search engines: Google, Yahoo, Bing, MSN and AOL. Our search strategy focused on two categories of medications: opioid painkillers and stimulants. The following keywords were used for the purpose of this search: Tylenol 3, Tylenol #3, T3, Morphine, Hydrompohone, Dilaudid, Dexedrine, Ritalin/Adderall, and Pain Medications.

Results: Qualitative analysis of the verbatim revealed 5 themes and 34 sub-themes. Over-reporting the side effects of undesired alternatives, under-reporting of the therapeutic effects of the medication of choice, knowing the symptoms of the illness in advance of a visit, and threatening doctors about making complaints against them were among the most common aberrant behaviors recommended online.

Conclusion: Individuals with prescription medication dependence use a variety of aberrant medication seeking behaviors to obtain their medications of choice. They use online discussion to share these approaches with other patients. Prevention of prescription medication abuse requires a multidisciplinary approach and engagement of all stakeholders.

Introduction

Introduction

Prescription medications, after cannabis, are the second most commonly used drugs in all age groups in the United States. Evidence indicates prescription medication abuse has been associated with significant morbidity and mortality and imposes a serious burden to the health care system [1].

It is estimated that about half of all emergency department visits for drug misuse were attributed to prescription medication abuse [2]. From 1999 to 2016, more than 200,000 people died in the United States from overdoses related to prescription opioids. This number was five times higher in 2016 than in 1999 [3].

According to the Drug Abuse Warning Network of the United States, [4] over 1.2 million emergency department (ED) visits involved nonmedical use of prescription medicines, over-thecounter drugs, or other types of pharmaceuticals in 2011. Pain relievers were the most common type of drugs involved in medical emergencies and narcotic pain relievers were involved in 29 percent. According to this study, the overall medical emergencies related to nonmedical use of pharmaceuticals increased 132 percent in the period from 2004 to 2011, with opiate/opioid involvement rising 183 percent. Central nervous system (CNS) stimulants (e.g., ADHD drugs) have experienced an 85% increase in the short-term, a similar short-term rise observed for involvement of illicit stimulants (amphetamines/methamphetamine) (71%).

In the US, according to the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, past year nonmedical use of prescription drugs (opioids Citation: Siavash Jafari, Ashkan Nasr, Nazila Hassanabadi. Aberrant Prescription Medication Seeking Behavior Used by Prescription Drug Users to Obtain Prescription Medications from Physicians: A Qualitative Review of Webpages, Blogs and Forums. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 3(1): 2019. OAJAP.MS.ID.000555. DOI: 10.33552/OAJAP.2019.03.000555. Page 2 of 6 stimulants, tranquilizers and sedatives) was reported by 6.2% of 12-17 year-olds and 11.8% of 18-25 year-olds, mainly driven by nonmedical use of prescription opioids, which has remained stable in the past decade despite rising trend since the late 1990’s [5].

Americans constitute less than 5% of the world’s population; however, they consume 80% of the global opioid supply and 99% of the global hydrocodone supply [6]. From 1997 to 2007, retail sales of commonly used opioid medications (including methadone, oxycodone, fentanyl base, hydromorphone, hydrocodone, morphine, meperidine, and codeine) have increased from a total of 50.7 million grams in 1997 to 126.5 million grams in 2007 [7]. This is an overall increase of 149% with increases ranging from 222% for morphine, 280% for hydrocodone, 319% for hydromorphone, 525% for fentanyl base, 866% for oxycodone, to 1293% for methadone.

The Canadian Alcohol and Drug Use Monitoring Survey 2013 found that opioid pain relievers were used by 4.3 million (15% of Canadians aged 15 years and older) [8]. Of these users, 99,000 (2%) of all self-reported abusing their opioid painkillers. This number was 6% among youth aged 15 to 19. United States, in 2002, abuse of prescription drugs cost nearly $181 billion [9].

One US study found that depressive symptoms and suicidality were significantly associated with greater odds of any non-medical prescription drug use (NMPDU), with painkiller use representing the greatest correlate among college students [10]. Other studies indicate that early onset of NMPDU was a significant predictor of prescription drug dependence. These findings reinforce the importance of developing prevention efforts to reduce NMPDU and diversion of prescription drugs among children and adolescents [11].

Several studies have found that patients who obtain prescribed medications could share them with friends and family [11-14]. Mc Cabe, et al. in 2006 investigated the prevalence and factors associated with the illicit use of prescription stimulants and assessed the relationship between the medical and illicit use of prescription stimulants among undergraduate college students [15]. A total of 9,161 undergraduate students, attending a large, public, midwestern research university in the United States completed a self-administered web-based survey. Of them, 8.1% reported lifetime illicit use of prescription stimulants and 5.4% reported past year illicit use. The number of undergraduate students who reported illicit use of prescription stimulants exceeded the number of students who reported medical use of prescription stimulants for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The leading sources of prescription stimulants for illicit use were friends and peers [15]. Students may take stimulants to improve their concentration, stay awake on exam nights, or improve their academic performance [16,17].

Prescription drugs can be retrieved through doctors, theft, or forgery. Doctor shopping is one of the most common methods of obtaining prescription medications among those who abuse them [18]. Doctor shopping is the act of “filling overlapping prescriptions from more than one prescriber at more than two pharmacies.” Prescription medication users use a variety of approaches to obtain medications of their choice from prescribers.

Blogs, websites, online forums and social media are common and easy ways of sharing information. Ease of access, confidentiality and ability to hide one’s own identity makes online platforms lucrative for exchange of ideas and sharing personal experiences on obtaining the drugs of choice. In this study we try to explore the methods that prescription medication users share in online platforms to guide other users how to obtain their drugs of choice from prescribers.

Methods

Search strategy

We used a combination of keywords to search five main search engines: Google, Yahoo, Bing, MSN and AOL. Our search strategy focused on highly abused medication categories: opioids (painkillers) and stimulants. The following keywords were used for the purpose of this search: Tylenol 3, Tylenol #3, Morphine, Hydromorphone, Dilaudid, Dexedrine, Ritalin/Adderall, and Pain Medications. Also, our search included a combination of questions inquiring about how to obtain specific medications from prescribers, such as:

1. how to get narcotics from doctors?

2. How to obtain morphine, Oxy, Percocet, Tylenol #3 from doctors?

3. How to get ADHD medications from doctors?

4. How to obtain stimulants (Adderall, Ritalin, Dexedrine, amphetamines, dextroamphetamines) from doctors?

For each search engine we looked at all first 50 pages which provided 500 URLs. We included any website, blog, documents, online chat, forum, or any other communication records that provided information about obtaining prescription medication from doctors.

Data collection

We created an excel spreadsheet with columns for each of the categories of medications. The text of webpages and the relevant URLs of the webpages were copied and pasted into the table. Extracted content was reviewed in detail by two reviewers. All relevant text was collected and placed into the table under the related category.

Data analysis

We used summative content analysis to explore the approaches shared online to obtain prescription medications from prescribers. Summative content analysis involves counting and comparisons of keywords followed by the interpretation of the underlying context [19]. Two authors (SJ and PG) reviewed the content independently. Duplicate text was removed from the table. Text was coded based on relevance to the keywords. Themes and subthemes were identified for each category of medications in this study. Aberrant behaviors were identified through this process and were grouped in five main categories based on the themes that were created in the first step.

Results

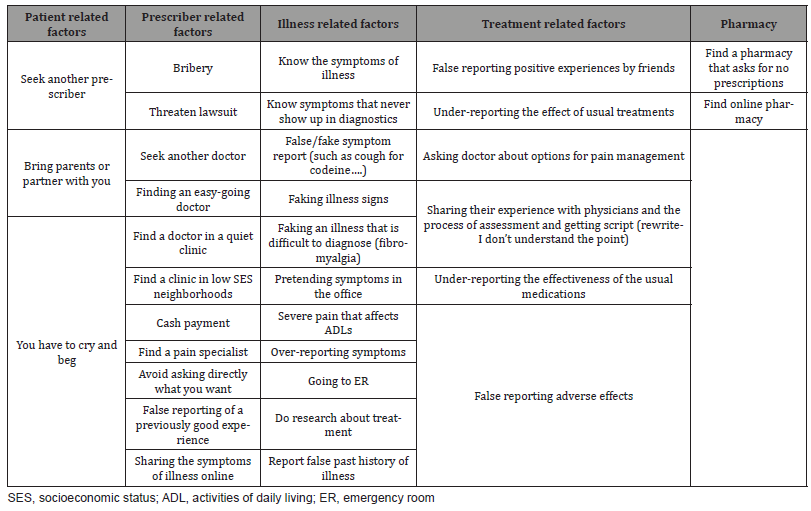

Qualitative analysis of the verbatim revealed 5 themes and 34 sub-themes that are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: The themes and subthemes that emerged from our qualitative assessment.

The following verbatim presents some examples of online advice and discussions among prescription medication users.

False reporting of symptoms

False reporting of the symptoms consists of over-reporting the severity of illness and symptoms. This approach was the most common approach suggested by users.

“What usually works for me, is complaining of some mysterious pain that prevents you from participating in normal activities. If that doesn’t work, there’s always threatening to sue them for malpractice, or then again, there is always flat out bribery. Hope this helps.”

“I would start by telling the doctor that what he is giving me isn’t working and you are taking more than the prescribed dose to try and rid yourself of the pain.”

“NEVER say you tried amphetamines and they helped – that’s seeking. if asked about drug use, say you smoked pot a few times and “didn’t like the feeling of being altered. Aside from that, go in and complain of not being able to concentrate - if this is a new doctor, tell him you were on Adderall (maybe 10mg twice a day) back when you were and it helped. but if he doesn’t want to prescribe an amphetamine right away, do NOT FIGHT IT! Take what he gives you then tell him it doesn’t work. Will someone post the Guide to Faking ADHD?”

Know the symptoms of illness

Knowing the symptoms of the illness was the second most common advice provided by users. They suggested others learn about the symptoms of illness in advance.

“The trick - seriously - is to visit a poor doctor in a poor area of town. Get your textbook list of requirements, pay cash for your appointment, and be the perfect patient. Each time ask for a little bit more painkillers for a little bit more pain. The doctors want to cover their asses legally and not go to jail or get sued, but it’s no hair off their back if you’re a lifetime “pain mgmt” candidate living on Roxy for the rest of your days.”

Faking illness signs

Some non-medical prescription medication users advised faking the signs of illness. For instance, coughing during a physician visit, pretending to be in severe pain, or pretending to have the signs and symptoms of ADHD.

“Start moving all the time. Don’t pay attention to anything. Don’t sit down and concentrate for more than a minute.’’

False reporting of adverse effects

Some users suggested false reporting of side effects related to the current medications and asking for their alternative and desired medication.

“Tell them pills upset your stomach and you have a bad cough.”

Find a pharmacy that asks for no prescriptions

Using online pharmacies or finding local pharmacies that ask for no prescriptions was another common approached shared among members.

“You might be able to find a pharmacy that will sell it to you without a prescription, in a lot of states, i daresay most, it’s legal. I made a topic about it a while back.”

Bring parents or partner with you

Some suggested bringing a family member to the appointment to legitimize complaints and illness.

“Dude, definitley bring your mom with you. I got a bs adderal script when I was 19. I bullshitted my dad into believeing I got an ADHD problem (cause i did lots of research). So, he comes in the doc office with me, was backing up my story to the doc. Doctor didn’t think twice about writing me a script. You definitely got to sell it to your mom though, parents add a little bit more legitimacy to the whole thing.”

Discussion

In this study we investigated the approaches that nonmedical users of prescription medications share online to access prescription opioids and stimulants. Findings of this study revealed that individuals who seek prescription medications use a variety of aberrant drug seeking behaviors to obtain their medications of choice. Most of these approaches have good face validity such as: knowing the symptoms of illness, having a family member along with you during the visit, finding a clinic in a low socioeconomic status (SES) area, avoiding asking directly for the medication of choice, going to the emergency room (ER), crying in pain, finding an easy-going physician and paying cash.

Others utilize unacceptable and abusive approaches such as: reporting a false past medical history, bribing the provider or the pharmacy, threatening a lawsuit, finding an online pharmacy, reporting fake symptoms, exaggerating pain severity, reporting symptoms that are difficult to diagnose (fibromyalgia), and finding a pharmacy that asks for no prescription.

Reducing non-medical use of prescription medications requires engagement of all stakeholders, including the prescribers, patients, health service organizations, and pharmacies. Provider factors can focus on educating the physicians to perform indepth assessment of patients prior to initiation of any treatment plan. Physicians should be aware of the potential risk of abuse of prescription medications. Developing clinical practice guidelines would help providers keep updated about available treatment options and benefits and risks related to each treatment [20,21]. Also, prescribers should be aware of the individual risk factors of non-medical use of prescription medications and the warning signs such as multiple doctoring, lost scripts, and lost medications [22,23]. Clinicians can use a combination of approaches to identify drug seeking behaviors. A detailed history and physical examination followed up by a thorough documentation of findings would be the first and the most important component of such an assessment [24]. A comprehensive and detailed assessment of symptoms and signs and consultation with the previous physician about the potential diagnosis, treatment history, medication dose, and aberrant behavior could be helpful. Validating the past medical history and the past treatments is very important and could be achieved by contacting previous providers, although this could be impossible for some patients [24-27].

Patient factors should take into account patient knowledge of drug-related harm, educating patients about benefits and risks of their medications and about avoiding medication sharing, development of patient handouts, safe storage of medications, avoidance from stockpiling and increasing access to drug addiction services, assignment of high-risk patients to a single-prescriber and single-pharmacy, and automated cancellation of multiple same-time prescriptions [28,29]. Also, lifestyle modification, alternative approaches such as physical therapy and rehabilitation, natural products, acupuncture and stress management could be other alternatives or adjuncts to prescription painkillers in the management of patients’ pain, rather than constantly increasing their painkiller dose. Regular monitoring programs such as pill counts, urine drug screens, limiting the dose per prescription and reducing the frequency of dispensing have been suggested by some researchers.

The greater “social acceptance” for using these medications (versus illegal substances) and the misconception that they are “safe” may be contributing factors to their misuse. Hence, a major target for intervention is the general public, including parents and youth, who must be better informed about the negative consequences of sharing medications with others that were prescribed for their own ailments. Equally important is the improved training of medical practitioners and their staff to better recognize patients who are at potential risk of developing nonmedical use. Such practitioners should consider potential alternative treatments as well as closely monitor the medications they dispense to these patients [5].

Health services factors should consider inter-provincial data sharing, prescription drug monitoring programs. Prevention of pill mills, pharmacist involvement and education about prevention of multiple prescription dispensing, and state law enforcement around prescription requirements [20,21,30-37]. Also considered should be the prevention of illegitimate online pharmacies, improving access to counselling and psychology services [38], increasing casemanagement services, and increasing treatment opportunities and services for prescription medication dependence [38-40].

Pharmacies are one of the main pillars of patient care and can take an active role in preventing and reducing prescription medication abuse. Reporting aberrant behaviors such as any modified prescription to the prescriber, establishing a lock-in program, [36] validating any out of range doses of prescriptions, reminding and validating early refills, securing the storage of sensitive medications, establishing a multidisciplinary controlledsubstance inventory system, and working with local, state, and federal authorities in controlling substance abuse, including participation in state prescription drug monitoring programs. Other approaches include encouraging participation in appropriate prescription disposal programs and complying with controlledsubstance reporting regulations [41,42].

In conclusion, non-medical use of prescription medications in Canada and the United States is a public health problem and requires multidisciplinary approach. Non-medical use of prescription medications poses significant risks to individuals and families and significant costs to the health care system. Individuals who use not-medically-indicated prescription medications share aberrant drug seeking behavior in social media and educate others on the approaches to obtaining prescription medications from physicians. To deal with this matter, engagement of all stakeholders, including the prescribers, patients, health service organizations, and pharmacies is required.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Hernandez SH, Nelson LS (2010) Prescription drug abuse: insight into the epidemic. Clin Pharmacol Ther 88: 307-317.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2019) Highlights of the 2011 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) findings on drug-related emergency department visits.

- Seth P, Rudd R, Noonan R, Haegerich T (2018) Quantifying the epidemic of prescription opioid overdose deaths. Am J Public Health 108(4): 500-502.

- Drug Abuse Warning Network (2018) The DAWN Report. National estimates of drug-related emergency department visits 2011.

- Martins SS, Ghandour LA (2017) Nonmedical use of prescription drugs in adolescents and young adults: not just a Western phenomenon. World Psychiatry 16(1): 102-104.

- Kuehn BM (2007) Opioid prescriptions soar: increase in legitimate use as well as abuse. JAMA 297(3): 249-251.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2018) 2007 World Drug Report.

- Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey 2013.

- (2004) Office of National Drug Control Policy. The economic costs of drug abuse in the United States, 1992- 2002, Pub. No. 207303.

- Zullig KJ, Divin AL (2012) The association between non-medical prescription drug use, depressive symptoms, and suicidality. Addict Behav 37(8): 890-899.

- Mc Cabe SE, West BT, Morales M, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ (2007) Does early onset of non-medical use of prescription drugs predict subsequent prescription drug abuse and dependence? Results from a national study. Addiction 102 (12): 1920-1930.

- Boyd CJ, Mc Cabe SE, Cranford JA, Young A (2007) Prescription drug abuse and diversion among adolescents in a southeast Michigan school district. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161(3): 276-281.

- Wilens TE, Gignac M, Swezey A, Monuteaux MC, Biederman J (2006) Characteristics of adolescents and young adults with ADHD who divert or misuse their prescribed medications. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45 (4): 408-414.

- Du Pont RL, Bucher RH, Wilford BB, Coleman JJ (2007) School-based administration of ADHD drugs decline, along with diversion, theft, and misuse. J Sch Nurs 23(6): 349-352.

- Mc Cabe SE, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ (2006) Medical use, illicit use and diversion of prescription stimulant medication. J Psychoactive Drugs 38(1): 43-56.

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Logan J (2009) Effects of modafinil on dopamine and dopamine transporters in the male human brain: clinical implications. JAMA 301(11): 1148-1154.

- Teter CJ, Mc Cabe SE, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ, Guthrie SK (2005) Prevalence and motivations for the illicit use of prescription stimulants in an undergraduate student sample. J Am Coll Health 53(6): 253-262.

- Sansone RA, Samsone LA (2012) Doctor shopping: a phenomenon of many themes. Innov Clin Neurosci 9(11-12): 42-46.

- Kondracki NL, Wellman NS, Amundson DR (2002) Content analysis: review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. J Nutr Educ Behav 34(4): 224-230.

- Hughes MA, Biggs JJ, Thiese MS (2011) Recommended opioid prescribing practices for use in chronic nonmalignant pain: a systematic review of treatment guidelines. J Manage Care Med 14: 52-58.

- Franklin GM, Mai J, Turner J, Sullivan M, Wickizer T, et al. (2012) Bending the prescription opioid dosing and mortality curves: impact of the Washington State opioid dosing guideline. Am J Ind Med 55(4): 325-331.

- Pierce GL, Smith MJ, Abate MA, Halverson J (2012) Doctor and pharmacy shopping for controlled substances. Med Care 50(6): 494-500.

- Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Dhalla IA, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN (2011) Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain. Arch Intern Med 171(7): 686-691.

- Salinas GD, Susalka D, Burton BS, Roepke N, Evanyo K, et al. (2012) Risk assessment and counseling behaviors of healthcare professionals managing patients with chronic pain: a national multifaceted assessment of physicians, pharmacists, and their patients. J Opioid Manag 8(5): 273-284.

- Upshur CC, Luckmann RS, Savageau JA (2006) Primary care provider concerns about management of chronic pain in community clinic populations. J Gen Intern Med 21(6): 652-655.

- O Rorke JE, Chen I, Genao I, Panda M, Cykert S (2007) Physicians’ comfort in caring for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Am J Med Sci 333(2): 93-100.

- Fox AD, Kunins HV, Starrels JL (2013) Which skills are associated with residents’ sense of preparedness to manage chronic pain? J Opioid Manag 8(5): 328-336.

- Johnson EM, Porucznik CA, Anderson JW, Rolfs RT (2011) State-level strategies for reducing prescription drug overdose deaths: Utah’s prescription safety program. Pain Med 12(Suppl 2): S66-S72.

- Mc Cauley JL, Back SE, Brady KT (2013) Pilot of a brief, web-based educational intervention targeting safe storage and disposal of prescription opioids. Addict Behav 38(6): 2230-2235.

- (2012) Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs. An assessment of the evidence for best practices.

- (2012) Drug Enforcement Administration. Holiday CVS final order reveals gross negligence by two CVS pharmacies in Stanford, USA.

- Rigg KK, March SJ, Inciardi JA (2010) Prescription drug abuse and diversion: role of the pain clinic. Journal of Drug Issues. 40(3): 681-702.

- Singleton TE (1977) Missouri’s lock-in: Control of recipient misutilization. J Medicaid Management 1(3): 10-17.

- Chinn FJ (1985) Medicaid recipient lock-in program - Hawaii’s experience in six years. Hawaii Medical Journal 44(1): 9-18.

- Blake SG (1998) Drug Expenditures: The effect of the Louisiana Medicaid lock-in on prescription drug utilization and expenditure. Drug Benefit Trends 1:72.

- Mitchell L (2009) Pharmacy lock-in program promotes appropriate use of resources. J Okla State Med Assoc 102(8): 276.

- Tanenbaum SJ, Dyer JL (1990) The dynamics of prescription drug abuse and its correctives in one state Medicaid program. American Medical Association, Department of Substance Abuse. Wilford BB, pp.229-238.

- Kresina TF, Lubran RL (2011) Improving public health through access to and utilization of medication assisted treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health 8(10): 4102-4117.

- Agerwala SM, Mc Cance Katz EF (2012) Integrating screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) into clinical practice settings: a brief review. J Psychoactive Drugs 44(4): 307-317.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2001) Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems: recommendations from the guidelines working group. MMWR 50(No. RR-13): 1-35.

- American Pharmacists Association (2003) Pharmacists’ role in addressing opioid abuse, addiction, and diversion. J Am Pharm Assoc. 54(1): e5-e15.

- The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (2016) Therapy and Patient Care: Specific Practice Areas-Statements. ASHP Statement on the Pharmacist’s Role in Substance Abuse Prevention, Education, and Assistance.

-

Siavash Jafari, Ashkan Nasr, Nazila Hassanabadi. Aberrant Prescription Medication Seeking Behavior Used by Prescription Drug Users to Obtain Prescription Medications from Physicians: A Qualitative Review of Webpages, Blogs and Forums. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 3(1): 2019. OAJAP.MS.ID.000555.

Physicians, Prescription, Medications, Drug, Non-medical, Aberrant behaviors, Webpages, Blogs, Forum

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.