Research Article

Research Article

A Qualitative Approach to Codependence in Men: Effects on Romantic Relationships

David Tolossa1*, Bina Parekh2 and Beatriz Lopez2

1San Bernardino Department of Behavioral Health, San Bernardino, California, USA

2The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Anaheim, California, USA

David Tolossa, San Bernardino Department of Behavioral Health, San Bernardino, California, USA.

Received Date: May 20, 2021; Published Date: July 16, 2021

Abstract

Growing up in an alcoholic home has several deleterious effects on those experiencing the alcoholic environment. These experiences often affect future romantic relationships in the form of codependence. The experience of individuals with codependent traits typically involves low self-esteem, low self-confidence, inappropriately self-sacrificing and enmeshment in a dysfunctional relationship. There is a vast literature base on codependency and female partners. However, there is a lack of research concerning how males are affected by codependency. The purpose of this research study was to identify how males are affected by codependence using a qualitative approach. Results revealed 6 master themes that occurred across transcripts in varying frequencies. Each theme was comprised of 3 subthemes. The six themes were Unrelenting Standard, Maladaptive Coping, Adopting the Role of Protector, Difficulty Communicating one’s Needs, Struggle in Sexual Aspects of Relationships and Difficult Family Upbringing. Thematic analysis revealed that individuals from an alcoholic home experience struggle in romantic relationships due to the influence of their childhood environment.

Keywords:Codependency; Addiction; Alcoholism; Romantic relationships

Introduction

Codependency is a condition resulting from alcoholic parentage or exposure to an alcoholic environment [1]. However, simply being a child of an alcoholic does not indicate codependency. Whereas being an Adult Child of an Alcoholic (ACOA) indicates alcoholic parentage. Codependency refers to the characteristics developed in response to living in an environment with an individual affected by addiction. To be labeled codependent, means that the individual may display learned behaviors of self-defeating, chronic guilt, untrusting and over controlling behaviors. These learned behaviors ultimately lead to a diminished ability to participate in loving relationships in response to living with the individual who suffers from addiction [2,3]. Codependent individuals live with the delusions that “there is nothing wrong with my family” and general denial of problems within the family system that serve to diminish conflict between members of the family [4,5]. Furthermore, the relationship serves the codependent much like an addiction wherein the drive to change their partner or “fix” them becomes their sole focus [6]. Many times, the codependent individual neglects him/herself in order to take care of his/her spouse or loved one with chemical dependency problems. The codependent may ignore his/her own needs and often feels powerless in a relational dynamic that is difficult to change.

It is estimated that 8 to 10 million Americans suffer from alcoholism. Since codependency is a potential result of growing up in an alcoholic environment it is estimated that an additional 30 million are therefore affected by the alcoholic in some way [7]. Furthermore, per the Children of Alcoholics Foundation, nearly 22 million Americans over the age of 18 are Adult Children of Alcoholics. These striking statistics indicate a severe problem in the codependent community. However, as noted earlier, treatment with this population may prove difficult as they deny having issues within the family system [6]. Moreover, the effects of being raised in an alcoholic environment on the ACOA’s future relationships have been documented for women.

The deleterious effects of living in an alcoholic environment have been noted in women with codependency. The learned behaviors from said environment carry through to the ACOA’s romantic relationship which can affect their level of intimacy with their partner. They may experience loneliness and reluctance to be open to feelings. The ACOA may take the behaviors they learned during childhood and apply those behaviors to their adult romantic relationships. During childhood, it is reported that children growing up in the alcoholic home learn to suppress their feelings [6]. According to Viorst, the child adopts premature autonomy wherein the child learns to “grow up too fast” thus forcing them to solve the problems of others [8]. In relationship, this may translate into significant relationship difficulties. Although patterns of codependence seem to be heavily weighted toward cultural scripts one may find that aside from culture alone, there may be a transgenerational transmission component to the codependent behavioral characteristics. For example, in a family where alcoholism passes through generations, codependence may affect those members of the system living with the alcoholic.

Statement of the problem

Codependency is a well-researched topic among females and stereotypically wives of alcoholic men. Research shows that wives with alcoholic husbands tend to display symptoms of codependency [6]. While men may stereotypically take on the burden to provide for their family resulting from childhood parentification, Noriega et al argues that codependent women take on a “submissive script” that informs their behaviors from childhood to adulthood [6]. Noriega et al suggests that young girls in the alcoholic home experience a “grow up fast and help others” script that informs their codependent behaviors. This suggests that women who grow up in an alcoholic home enter an unhealthy secondary symbiosis with their alcoholic fathers which translates into adulthood, expressing their script in romantic relationships [6]. Secondary symbiosis refers to the role confusing between child and parent where the first-born daughter will parent the parents who have taken a childlike role [6]. This suggests that women from alcoholic homes are taught from a young age that caring for others is the utmost value they can provide to future relationships.

While most treatment is focused on coping ability among codependent wives or female partners, there is a lack of research showing the male perspective of codependency. That is, how do males with codependency cope with an alcoholic environment and how does that affect their romantic relationships in the future? There are several studies that show how females with codependency learn these codependent traits in childhood but there is scarce literature to reveal any unique experiences as a male growing up in an alcoholic environment. Research suggests that one’s attachment relationship and childhood environment influence one’s future relationships as the parental relationship serves as a model for their children [9]. As such, growing up with an alcoholic member of the family in turn has effects on their future relationships. However, current research focuses on the effects of codependency on female partners and wives of alcoholics. The current study aims to add to the growing literature on codependency by incorporating the male perspective of codependency. This study utilized a mixed design, where an open-source codependency rating scale was used to gauge how codependent traits present in participants and a semi-structured interview was conducted with 10 male codependents to explore the richness of their experience and how their childhood with alcoholic parentage has influenced their current behaviors with their current romantic relationships. By analyzing these interviews, themes may emerge that may open innovative treatment avenues for codependency in males. The study may potentially reveal how the codependent male experience may be uniquely different from his female counterparts. There is a likelihood that culture and diversity variables influence how the individual perceives their alcoholic environment. Understanding this population’s unique experience may uncover ways to better treat and assess males with codependency.

Methods

Participants

Participants were principally recruited via colleague referral and snowball sampling method. The participants in this study consisted of adult males 18-50 years of age who grew up in an alcoholic home and identified as codependent. The researcher included 6 participants, which met the sampling needs of qualitatively exploring the themes of male codependent’s experience navigating romantic relationships. It was projected that once the saturation point of 6 participants was reached, it was unlikely that additional collection of data would add to the themes explored. In a phenomenological research tradition, the size of the participants can be between 2 and 25 therefore, selection of participants should reflect and represent the homogeneity that exists among the participants’ sample pool [10]. Participants included in the study must have had a history of at least one break-up and identify as codependent.

Measures

Demographic Questions: Demographic data regarding each of the participants age, ethnicity, gender, number of break-ups, number of alcoholic parents, years spent living with the alcoholic, and any history of alcohol use/abuse was be gathered via a questionnaire created by the researcher prior to the interview. Please see Appendix for a list of such demographic questions.

Semi-Structured Interview Questions: After review of the literature on codependency, a semi-structured interview instrument was constructed by the researcher as the primary method of data collection for the proposed qualitative study. The semi-structured interview consisted of 14 questions. The following content areas were covered in terms of experience living in an alcoholic home, familial responsibilities, challenges in romantic relationships, selfperception. Please see Appendix B for a list of semi-structured interview questions. The semi-structured interview questions were aimed at uncovering potential unique experience of the male codependent. The questions were open-ended, which allowed for the possibility to uncover the richness in experience from our male participants. Furthermore, the open-ended questions prompted the participant to bring to light any content not previously considered by the researcher.

Procedures

The researcher obtained participants through colleague referral and snowball sampling. Researcher colleagues informed potential participants of the inclusion criteria and relayed the information to the researcher for final approval into the interview. If the participant was interested in being a part of the study, he then contacted the researcher directly where the researcher explained the nature of the study and set up a time to meet with the subject in a private meeting area. Upon meeting the criteria for participation in the posed study, the researcher discussed the nature of the project, verbally reviewed their rights as a participant and provided an informed consent statement. Additionally, the researcher reviewed the inclusion criteria with each subject to again ensure he was appropriate for this study. Once the participant agreed to participate in the study, a meeting to conduct the semi-structured interview in a designated office at a clinical private practice was conducted.

The subjects that meet eligibility criteria were asked to voluntarily participate in the study. After signing the informed consent, the subject completed a demographic questionnaire, a brief co-dependency screener and a semi-structured interview which took approximately an hour and a half to complete. The codependency assessment tool was a series of twenty questions that load onto traits associated with codependency. A score of 5 or more indicated that our participant has had codependent traits that interfere with their lives. Participants were informed that the interview was audio recorded and transcribed for further analysis. Subjects were informed that all information will be kept confidential. Any identifying information was separated from their responses and excluded during transcription to ensure their confidentiality and maintain the data’s integrity. The researcher transcribed all the recorded interviews. A second reader also reviewed the transcriptions and she signed confidentiality agreement. The second reader was used to calculate inter-rater reliability.

Upon completion of the semi-structured interview, a verbal and written debriefing statement was provided with the contact information of the researcher and any necessary referrals. Please refer to Appendix C and D for informed consent and debriefing statements.

Participants were offered compensation in the form of a 5-dollar Starbucks© gift card. Participants were reminded of their contribution to the codependency literature as there is scarce literature on the topic of solely male codependents. Participants that request a copy of the results and recommendations following the completion of this research project will be provided with this information by the researcher. All transcriptions were housed on a password protected computer and all information was de-identified to protect confidentiality of the participants. Additionally, the data will be kept for a total of 4 years and then destroyed.

Results

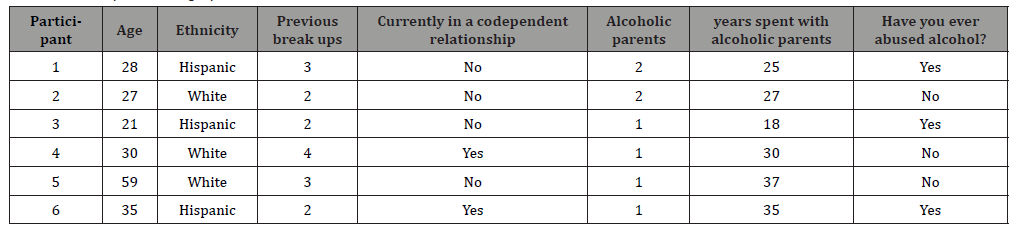

The interviews for this study were reviewed utilizing interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA). All transcripts used pseudonyms (P01, P02, etc.) instead of the participant’s names to help ensure anonymity and confidentiality. The transcripts of the interviews were examined to find interpretative comments and themes. The participant pool consisted of 6 men, aged 21 to 59 years old. All interviewees endorsed experiences living in an alcoholic home. All participants reported having lived with either one or both of their alcoholic parents for most of their lives. In their own romantic relationship participants endorsed having on average 2-4 break ups prior to their current relationship. Although 4 out of 6 participants denied experiencing difficulties in their relationship from codependent traits, all participants met or exceeded the score threshold on our Codependency self-assessment. A score of 5 on the self-assessment indicates that codependent traits may interfere with your relationship; our participants earned scores ranging from 6 to 13. The sample consisted, 3 men who identified as Hispanic and 3 men who identified as Caucasian/white. Table 1 contains participant demographics for each individual (Figure 1).

Table 1:Participant Demographics.

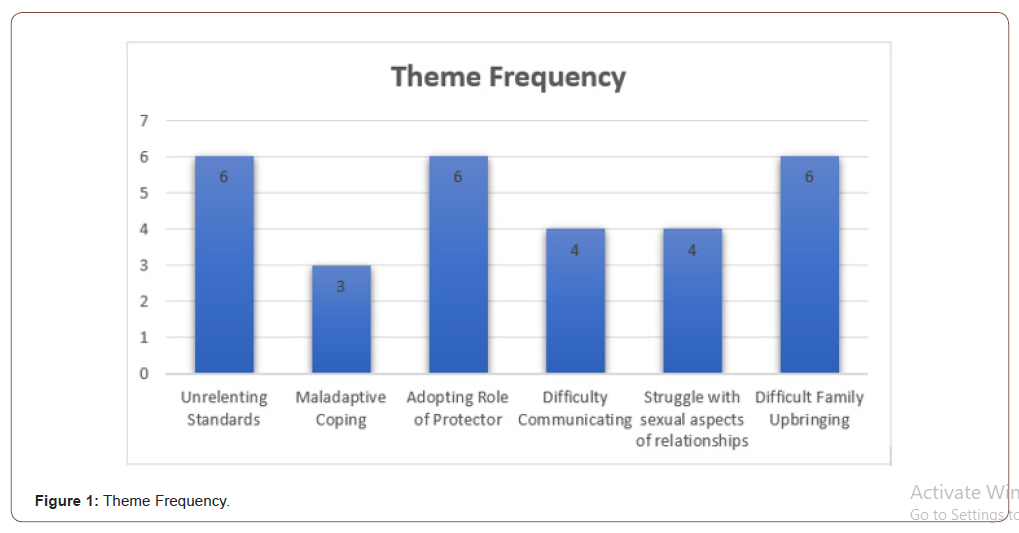

Overall, analysis revealed 6 master themes that occurred across transcripts in varying frequencies. Each theme was comprised of 3 subthemes. In the last step of the IPA analysis, a second rater, was trained on the themes identified. She then reviewed all protocols to determine the theme frequency. This process was intended to improve inter-rater reliability. An inter-reliability was calculated and revealed a Cohen’s kappa of .71, indicating the inter-rater reliability for the themes was acceptable. A review of all master themes and their respective subthemes is provided below.

Theme 1: Unrelenting Standards

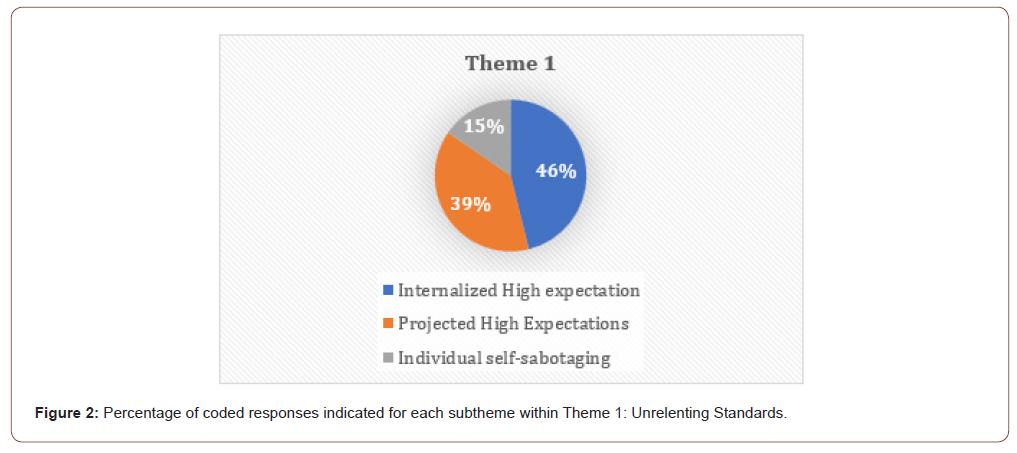

The theme of Unrelenting Standards is characterized by selfprescribed perfection or rigid rules. The individual may adhere to a personal set of unrealistic set of goals and aspirations that may lead to self-sabotaging due to expectations that are unattainable. This theme is multifaceted and best characterized by (a) internalized high expectations, (b) projected high expectations, (c) individual self-sabotaging (Figure 2).

Six participants reported rigid and unrelenting expectations of themselves. The drive toward perfectionism and personal code of values, moral, and high expectations were repeatedly attributed to a lack of standards within their family system. Participants were honest and open regarding their personal high standards. One aspect of their unrelenting standards was prominent enough to be considered a subtheme; Internalized high expectations. This subtheme was exemplified by the individual’s tendency to become critical of their own actions thus resulting in an inability to accept their own faults. The following quotes exemplify the perceived internalized high expectation.

“I saw a lot of wrong in growing up so I didn’t want that and I didn’t want that in a relationship, so I did the complete opposite and that’s how I built myself.” (Participant 4)

“I try to be as courageous and respectful of living areas and her emotional areas. I need to be all thick and then cool. “(Participant 1)

“I pretty much do everything I can do to make her life good and comfortable” (Participant 2)

Finally, approximately 5 participants engaged in a process where they placed (or projected) their internalized high expectations upon their relationship or their partner. “Projected high expectations.” Additionally, two participants engaged in self-sabotaging behaviors. Self-Sabotaging behaviors were characterized as stretching themselves too thin which ultimately led to burn out or taking on the burden of ensuring relationship success. Furthermore, self-sabotage occurred when individuals set personal expectations too high and become discouraged by their inability to meet the goal. Within the relationship this process often hindered their ability to make progress toward life goals due to selfdoubt. Because individuals were raised with high expectations from their families, this led to a fear that they would be unable to either meet set expectations or they would undermine their own success by not following through on their personal or relationship goals. In general, it appeared that participants would engage in unrelenting standards as a result of their negative experiences living in an alcoholic home. Participants likely considered their upbringing as a reason to avoid difficulty rather than using it as fuel for their future success. The active resistance to follow in the same footsteps as their parents may have resulted in the higher expectation of self, partner and relationship. These phenomena are exemplified in the following quotes.

“It feels like a heavy responsibility to provide and kind of have it all together” (participant 3)

“I feel like I put a lot more pressure on myself in this relationship” (Participant 3)

“My parents kind of always instilled in me that I need to reach for the stars. No, I’ll never settle for less. Those expectations of me kind of result how I was” (Participant 6)

“I try to not be so self-absorbed and made sure of that…I guess it goes back to my expectation being too high…they expect too much of me even though I know that I expect too much, I still expect it too.” (participant 6)

Theme 2: Maladaptive Coping

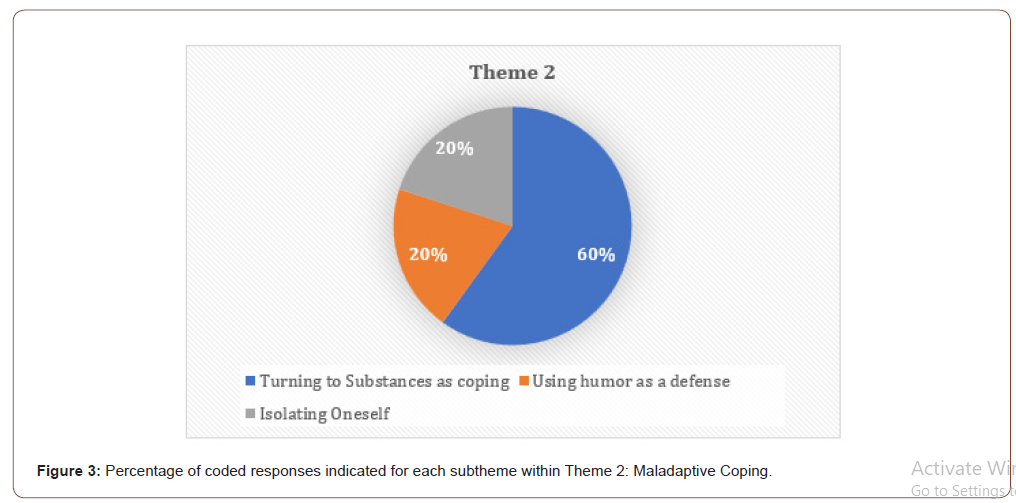

The theme of Maladaptive Coping refers to the coping response which the individual will utilize when faced with difficulty. For example, participants discussed attempts at coping with their chaotic family environment by engaging in substance use, isolation or utilizing humor as a means of avoidance. These behaviors tend to increase anxiety and stress as they only serve to prolong issues rather than address them in the moment. This theme is best characterized by (a) turning to substances as coping, (b) using humor as a defense, and (c)isolating oneself (Figure 3).

Half of the participants reported maladaptive coping styles in response to their difficult experiences with alcoholic parentage. Respondents were open and honest regarding how they responded to their negative upbringing stating that by and large, substance use and abuse was a primary method of coping. As such, a subtheme, Turning to substances as coping, was deemed appropriate to capture their experience of coping with family systemic stress. The following quotes exemplify how substances re used as a method of coping.

“I believe I kind of continued the legacy in the sense that I’m so much like my father that I drink” (Participant 6)

“I think ultimately that had a big part in why I decided to start experimenting with alcohol and drugs to try and cope with that” (Participant 1)

Finally, participants endorsed using humor as a defense. It appeared that in response to difficult situations, making light of the negative was utilized as a means for coping. By engaging in this defense mechanism, it appeared that participants were able to control outcomes based on their behaviors. Although on the surface it may appear using humor is a relative defense, it is clear by the context of their responses that humor was a means of avoiding the difficult realities of their chaotic family situation. Additionally, participants reported isolating behaviors in response to negative family stressors. Participants turned inward and withdrew from a difficult situation. These phenomena are best exemplified in the following quotes.

“Yeah um a lot of humor. I try to use that a lot. Appropriately and inappropriately. I don’t like confrontations, so you know let’s make it light, lets laugh about it. So, you know definitely a lot of humor and comic relief” (Participant 1)

“I’ve always been a quiet guy. I’d just go out in the backyard by myself or go in a different room by myself and just lay on the floor for like hours.” (Participant 2).

“So, you know, I’ve been known to withdraw and isolate and thinks like that, um avoid.” (Participant 1)

Theme 3: Adopting the role of “protector”

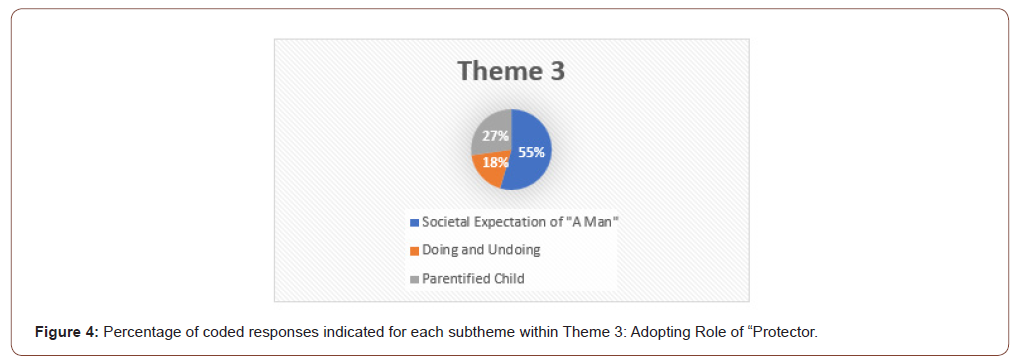

The theme of Adopting the role of “Protector” refers to the role that the individual takes on within the family system. The individual may perceive societal or cultural expectation to meet the demands of the protector role. This role may play out in relations to romantic other, or with parents in the family system. This theme is best characterized by (a) societal expectations of “A Man,” (b) Doing and undoing, and (c) Parentified Child (Figure 4).

Six participants reported that they adopt the role of “protector.” It appeared that this theme was linked with the desire to maintain high expectations. Whereas Theme 1 related to the individual set of value and moral code, Theme 3 seemed to present itself behaviorally. Individuals that acted out their internalized high expectations attempted to meet the stereotypical image of “a man.”. Participants discussed how being “a man” necessitated them to respond by becoming overly masculine and conforming to the rigid role assignment of male stereotypes. The following quote exemplifies these phenomena.

“I’m responsible for maintenance of the home, the earnings, protecting the family from anything, internal or external” (Participant 5)

“In general, there um a sense of being like a provider and being this big burly dude who you know is masculine and you know leaves the nurturing traits to feminine traits.” (Participant 1)

“Other than being protective of my girlfriend and wanting to be the one who brings home the bacon kind of thing. But I do like to be the one to provide and take care of people and everything” (Participant 2)

Participants who endorsed this theme also appeared to come from a parentified childhood. It seemed that by learning the various protector roles in their youth via the accelerated need to meet demands above their chronological age, they then took these learned behaviors into their romantic relationships. It appeared that by learning and acknowledging the faults of their alcoholic parent, they in turn did the opposite and overcorrected for their shortcomings. This was exemplified by several participants who discussed experiences having to take care of themselves or having to make up for old wrongs by engaging in reparative behaviors. For example, participants described times when they were required by a self-prescribed gender role to be a “provider,” a skill they learned in development. Furthermore, participants discussed experiences when they committed wrongs in their youth and felt they needed to be perfect as they matured to avoid making the same mistakes from the past.

“I can remember being 10 or less and wondering if like the rent or mortgage was going to get paid.” (Participant 1).

“Those were probably the toughest days cause my mom was constantly drunk…It was just difficult to see her go through that and feel more mature and more developed that your mom and stepdad in those tough situations” (Participant 002)

“…it constantly caused financial problems. There were some times where I had to get groceries from the church. My sister and I would be really hungry we’d eat brown sugar out of the pantry…I would go around with my friends and collect ‘fruit leathers’ just so we could have something to eat at home” (Participant 002)

Theme 4: Difficulty communicating one’s needs

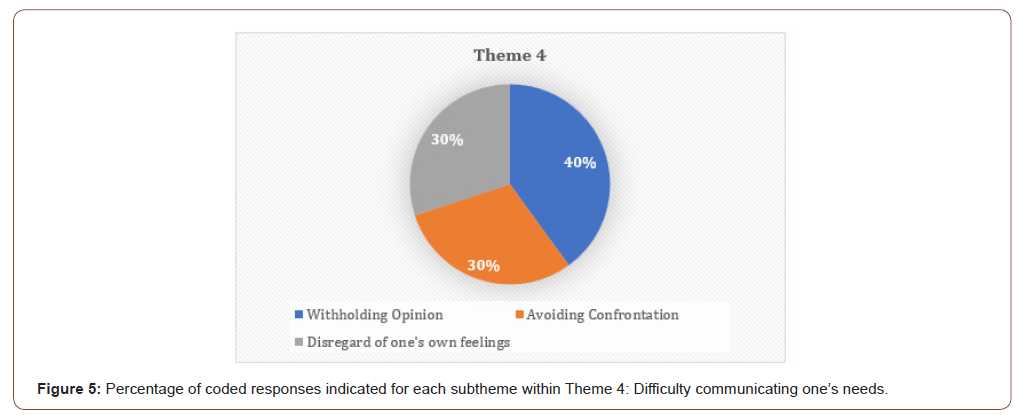

The theme of difficulty communicating one’s needs refers to the individual’s inability to advocate for their needs. The individual may suppress their desires in the service of others. This theme is best characterized by (a) withholding opinion, (b) Avoiding Confrontation and (c) disregard of one’s own feelings (Figure 5).

Four of the six participants reported that they have trouble in expressing their needs to partners. It appears that this may be a result of being raised in an alcoholic home environment. Participants who endorsed this theme endorsed that they often withhold their opinion to avoid confrontation therein disregarding their own feelings. Although Theme 4, relates to the global difficulty with communication it is however multifaceted suggesting that each sub theme may be overlapping in some way. Participants answering exemplify this theme.

“In my current relationship I’ve seen how communication breakdown can happen so easily and it can get so out of proportion and so twisted so fast.” (Participant 3)

“…for a while communication. Being able to appropriately express my needs and wants especially in the face of like conflict and confrontation.” (Participant 1)

“Expressing my mood now, not expressing my emotions…” (Participant 5)

“My Biggest one would probably be feeling able to speak my own mind.” (Participant 2)

Participants endorsing this theme noted that over time they felt as if they needed support in communicating their needs by turning towards siblings or others to voice their opinions. It appeared that participants were not confident in the ability of their partner to effectively meet their needs thus leading them to suppress their own wants and desires.

Theme 5: Struggle in sexual aspects of relationships

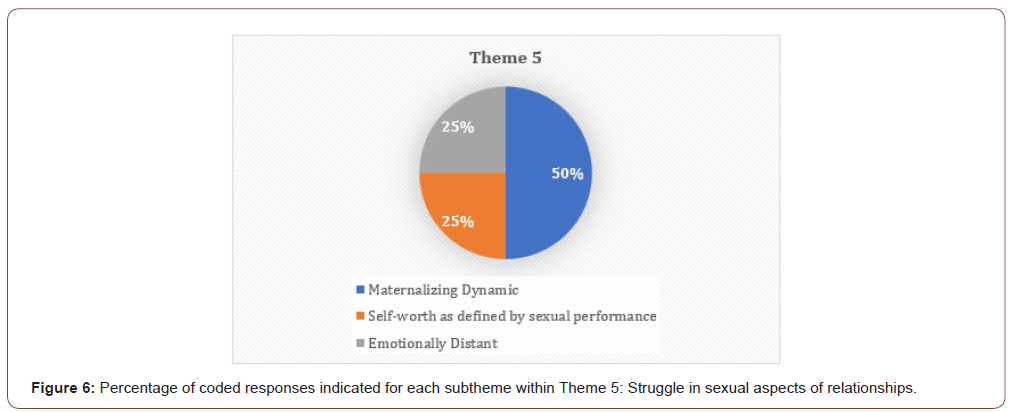

The theme of struggle in sexual aspects of relationships refers to the individual experience of difficulty in connecting to their partner sexually. The individual may feel inadequate in their ability to provide for their partner sexually. This theme is best characterized by (a) Materializing dynamic (b) Self-Worth as defined by sexual performance and (c) emotionally distant (Figure 6).

Four out of six participants endorsed this theme suggesting that meeting the sexual needs of a relationship proved to be an area of anxiety. Participants described that they actively sought out women to date who were “nurturers” and “motherly.” This brought to light the possibility that men from an alcoholic home may choose women who hold maternal characteristics. It appears that due to the perceived sexual inadequacy men might feel during relationships, they may become emotionally distant or cold toward their partner as a protective measure. The following quotes best exemplify this theme.

“I was kind of neglected a lot when I was a child, so I didn’t know who was there for me, so that’s where my trust issues come from, I guess.” (Participant 4)

“I feel like our sexual experiences could be more outgoing. I feel like their very conservative.” (Participant 6).

“She was really my first sexual experience and so that was kind of like love and she was freaky. Turned me freaky.” (Participant 5)

“So, my mom is extremely codependent. So, there’s been a sense of like, trying to recreate that, you know and have people in my life who will do what they can for me even with negative ways. To support me in ways that also hurt themselves.” (Participant 1).

Theme 6: Difficult family upbringing

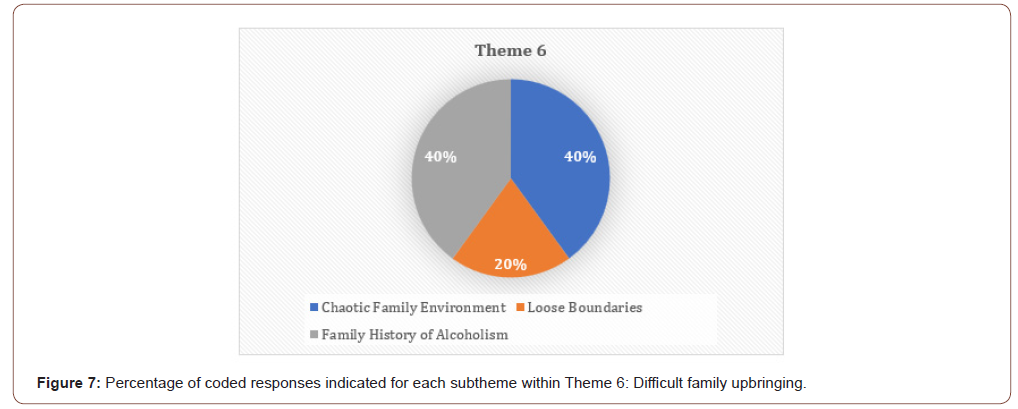

The theme of difficult family upbringing refers to the experience living in an alcoholic home. The family dynamics which influence the individual personality and relational behaviors are captured within this theme. This theme is best characterized by (a) Chaotic Family Environment (b) Loose Boundaries and (c) Family history of alcoholism (Figure 7).

Six participants endorsed experiences in a chaotic family upbringing. Participants described environments in which boundaries were not respected, and/or, too loose. Participants were able to articulate that their experience living in an alcoholic home influenced their day to day experience in relating to others. It appeared that some participants were reluctant to acknowledge the effect alcoholism in the home had taken on them. These participants often tried to minimize and underplay their dysfunctional home environment by describing the chaos in a matter of fact and nonchalant fashion. The following quotes best exemplify this theme.

“You know it was like fingers pointed, loud aggressive tones. Seemed like someone was screaming all the time. I would stay out as long as I possibly could…because I knew what I’d be coming home too. You know, and whether its like dinner plates getting thrown at us, whatever it was. Like I just was like, I don’t want to be there” (Participant 1).

“so it was really tough at, during middle school with my, my mom and her husband... all the money went, went to their smoking and drinking. So, um, we even, like, got evicted from an apartment once… those were probably the toughest days, um, cause my mom was constantly drunk. Her boyfriend, he’d drink and play Xbox all day, didn’t work and, ah, and it affected her and obviously affected us… so I do recall there sometimes being, like, no food in the house other than, like, baking supplies. So, like, my sister and I would be hungry. We’d eat brown sugar out of the pantry because we were, like, so hungry.” (Participant 2).

“I saw a lot of negative things, my mom and dad fighting, and it’s something that I never wanted to see. And then, I felt like I was the one that got ignored, because I was the youngest, and all of this was going on. So ... It felt like I ... I was always left out. Like I didn’t belong.” (Participant 4)

“Lack of bond as a family. Black walling, yelling, screaming, no real physical abuse, but verbal abuse with daily occurrence.” (Participant 5)

“My mom crying. I hate it. Hated, absolutely despise when I would see my mom hurt. She was like an angel. And, um, and so seeing little someone who I also regard very highly, my dad would hurt someone who I love so much for me to learn.” (Participant 6).

Discussion

Research indicates that adverse childhood experiences have a lasting impact on the development of personality characteristics [11]. One of the potential deleterious effects of growing up in an alcoholic home is the development of codependency and codependent traits. According to the research, codependency refers to “the syndrome of pathological effects” resulting from having a parent or significant with addiction [3]. Often, the affected individual engages in behaviors of self-loathing, feeling internally inadequate, depression, anxiety, and somatization due to learned inability to cope in their alcoholic home [11].

Consequently, as individuals learn to navigate romantic relationships, they are unconsciously applying their learned experience from childhood onto their potential partner and their environment. As such, for those individuals that have experience growing up in an alcoholic home, one might conclude that being raised in that environment would in turn have adverse effects on their ability to effectively connect to romantic others and cope with the difficulties, responsibilities, and stressors of relationship dynamics. Research shows that some behaviors that result from an alcoholic home include feeling powerless, lacking intimacy, and caring a sense of personal inadequacy [6].

In and of itself, navigating romantic relationships can be a challenge for some individuals. For the individual that was raised in the chaos of an alcoholic home, the challenge may prove to be greater. While the literature suggests that codependency is not necessarily about the behaviors engaged in but rather how the individuals view themselves [12], the challenge to find healthy relationships becomes greater as feelings of internal shame, loss of personal identity, and feelings of inadequacy prevent the individual from making fruitful connections with others [13]. It appears that codependent individuals sacrifice their own needs through caretaking, guilt and manipulation; behaviors learned from alcoholic home environments.

The study found six primary higher order themes: (1) Unrelenting Standards, (2) Maladaptive Coping, (3) Adopting the Role of “Protector,” (4) Difficulty Communicating one’s Needs, (5) Struggle in Sexual Aspects of Relationships, and (6) Difficult Family Upbringing that appear to highlight the challenges that codependent men may face.

Unrelenting Standards

Unrelenting Standards, a term coined by Dr. Jeffery Young, refers to the early maladaptive core belief centered around perfectionism and hypocriticalness [14]. According to Young, individuals with unrelenting standards are often perfectionistic, display inordinate attention to detail and often underestimate how much better their performance is relative to the norm [14]. This behavior was observed in the present study as participants often described expectations of themselves and their relationship from a rigid and perfectionistic fashion. Inevitably, individuals with this maladaptive schema become overburdened by their self-prescribed standards which can in turn lead to lack of pleasure in life, health problems, or some form of dysfunction [14]. It appeared that for the participants in this study, applying high expectations and standards across all realms of their lives served as a mechanism of self-sabotage wherein they become immobilized to meet their goals due to their own high expectations of themselves and relationships. It appears that this behavior develops out of a need to correct the wrongs committed by their alcoholic home. To avoid the chaos, they experienced growing up, participants may have over corrected their drives thus leading to an unrelenting standards schema.

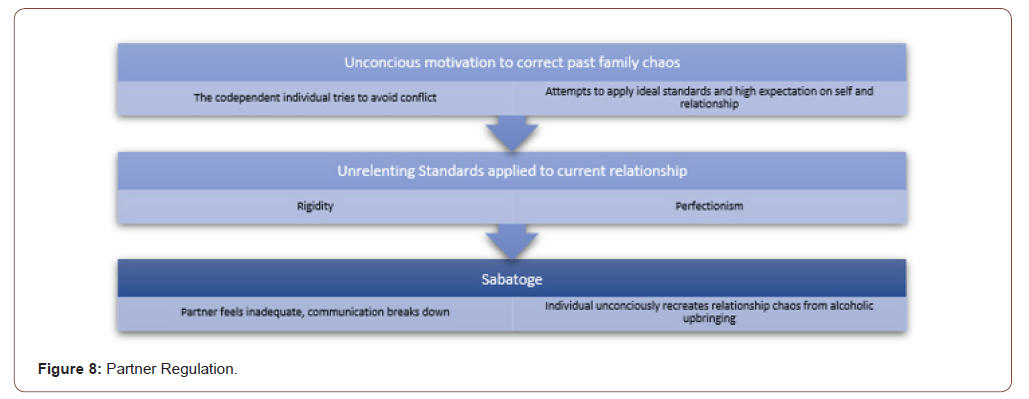

Individuals in relationship may unconsciously try to change their partner’s negative attributes through a process called Partner Regulation. According to Overall, individuals compare the qualities of some features of the self with a preexisting standard [15]. This indicates that the individual motivated to change some aspects of his/her partner may also be motivated to correct some past model of themselves. Meaning that the codependent individual may inherently understand the flawed nature of their upbringing and may be attempting to “fix” their inner flaws by addressing them within their partner. Individuals possess a chronically accessible mate and relationship ideal standard that predates a specific relationship [15]. It appeared that for the participants in this study, this “Ideal Standard” was far and above the reasonable standard that relationships require for positive outcome. It seems that implementing rigidity was employed to avoid conflict and chaos experienced during childhood. It is therefore due to the individual’s unrelenting standards that may lead the individual to unknowingly sabotage the relationship. This process is depicted in Figure 8. The process to attempt to regulate partner ideal standard leads to lower consistency between partner perceptions and ideal standards which motivated more strenuous regulation attempts overtime [15]. Due to the discrepancy between the individual perception of their partner and their ideal standard, it seems that participants in this study may be projecting their insecurities in the relationship onto their partners and actively trying to correct the process despite it reflecting their own self-misperceptions.

Inevitably the codependent male’s attempts at course correcting his relationship and fails, which has a deleterious effect his selfesteem, self-concept, and perception of his effectiveness within the relationship. These behaviors ultimately lead to self-sabotage wherein the individual experiences powerlessness to change that which is out of his control but continues to attempt to “fix” the discomfort felt around him. The literature supports the notion that with perfectionism comes unrelenting self-criticism and feelings of inadequacy [16]. The codependent male struggling to manifest the ideal relationship is caught in a losing situation where they experience loneliness, sadness, low positive emotion, guilt, and hopelessness due to higher levels of self-critical dispositions [16].

Based on the literature an individual’s self-compassion is tied to the individual’s reactions toward the worst events that happened to them in meaningful ways [17]. Therefore, one might conclude that for males who grew up in an alcoholic environment their level of self-compassion would be low. It appeared that for the participants in this study, having low self-compassion may have coincided with high expectations. When our participants are tasked with managing their day to day stressors with poor coping ability it seems that individuals turn their frustrations inward, blaming themselves for their background and shortcomings. On the other hand, the literature supports that for those individuals that retain higher levels of self-compassion their ability to moderate reactions to distress is also high [17]. Consequently, if the codependent male were able to build their sense of self-compassion, they may also be able to mitigate the negative influence alcoholic environments have had on their upbringing and lives thus far. Furthermore, by increasing self-compassion, it may serve as a protective factor to minimize occurrences of self-sabotage.

Maladaptive Coping

Facing and working through difficulty can be a challenging task for anyone. For the individual who has experienced life in an alcoholic home the task of coping with stress becomes that much more challenging. Individuals from an alcoholic home are raised in an environment where maladaptive coping skills (alcohol use/ abuse) are the foundation of the dysfunctional family system. The study found that 60% of our participants turned to substances as a means of coping whether it was drugs or alcohol. Additionally, it was found that 20% of the participants isolated themselves in response to the difficulty they faced. Finally, 20% of the participants utilized humor as a defense.

It was expected that many of the participants would endorse a history of substance use/abuse in their lifetime thus far. Given that the participants were raised in an alcoholic home it was anticipated that many of the participants may have been affected by their alcoholic parent’s model of negative coping. It was indeed confirmed that for an individual from an alcoholic home the likelihood of Citation: David Tolossa, Bina Parekh, Beatriz Lopez. A Qualitative Approach to Codependence in Men: Effects on Romantic Relationships. 4(4): 2021. OAJAP.MS.ID.000594. DOI: 10.33552/OAJAP.2021.04.000594. Open Access Journal of Addiction and Psychology Volume 4-Issue 4 Page 11 of 16 them engaging in their own substance use was higher. In a study by Chassin et al, they found that parental attachment, support and influence had a great effect on the developing child [18]. Therefore, given the parenting strategies and unconscious socialization messages conveyed, future substance use was indicated for those individuals who grew up in an alcoholic home.

While humor is considered a higher order and mature psychological defense mechanism, however, within the present the study it appeared that individuals utilized humor as a negative coping mechanism. That is, rather than confront the issues at hand or allowing themselves to be vulnerable, the participants appeared to use humor to control situations, avoid difficult emotionality and regulate their environment. However according to Miczo, an individual’s ability to use humor in response to interpersonal stress was moderately correlated to avoidance [19]. This suggests that the individual utilizing humor during times of interpersonal crisis can avoid their feelings of anxiety and transform them into a method of building attachment by attuning to their partner and creating a positive reaction [19]. Miczo found that the use of humor and loneliness were negatively correlated suggesting that individuals who use humor build social support through their ability to elicit positive reactions in others [19]. For the participants it appears that while they may be suffering in silence with the dysfunction of an alcoholic home their attempts to reach out for connection are made using humor. On the surface this appears positive because the individual is attempting to repair negative interactions through humor yet, despite his attempts to use humor he may still experience interpersonal distress. Thus, humor does not necessarily address the codependent males need for connection completely.

For 20% of the participants, it was reported that during times of high stress of interpersonal difficulty, the desire to isolate oneself was higher. Some participants reported that they preferred to “get away” and be alone. This behavior appeared to function as a protective strategy to remove oneself from the problem in order to self-soothe. In a study by Lopez et al, they found a relationship between isolation and later alcohol use in adulthood [20]. This finding is pertinent because it seems that for participants who come from alcoholic homes and also engage in self-isolative behaviors may be at higher risk for substance use. While the behavior of selfisolating and consuming alcohol to cope with difficulty are vastly different behaviors, it seems that at the core of these behaviors lies in the desire to avoid or “get away” from problems. In childhood it seems that during moments of powerlessness, participants self-isolated to cope. However, it seems that given the negative role model from alcoholic parents, self-isolating behaviors have the potential to evolve into alcohol consumptions to cope with stress. Of course, these behaviors are case dependent and does not propose with the utmost certainty should an individual isolate during stress that it guarantees they will abuse alcohol later in life. However, based on the literature base it appears that the likelihood of engaging in alcohol abuse behaviors may increase when individuals avoid vulnerable emotions, cope via escape and come from alcoholic homes.

Adopting the Role of Protector

Male gender roles reinforced by societal stereotypes create a challenge for men in the realm of developing a deep sense of emotional intelligence, understanding racial and gender inequality and meeting the expectation to fulfill the role of “protector.” Furthermore, from a young age, males are taught that their highest value is to dominate, control and succeed at all costs [21]. Men are taught that to be emotional is weak, to confide in others is failure, to rely on oneself is the epitome of strength and control. Growing up in an alcoholic environment further increases the challenge to navigate the environment, romantic relationships, and one’s identity. The study found that participants experienced an incredible pressure to meet the role of provider, protector and leader of the pack. Some of these cumbersome role expectations may have been influenced by the lack of positive modeling from alcoholic parents and the negative influence of toxic masculine ideals.

Men in conflict with gender roles often utilize psychological defenses where they use strategies to protect themselves from feelings of weakness by blocking awareness and expression of vulnerable emotions [22]. Presumably, a young boy growing up in an alcoholic environment would face his inherent limitation to change the chaos around him. Therefore, the development of psychological defenses to empower himself would likely match the gender role expectations set forth by society. It should come to no surprise that carrying these learned defenses into adulthood serves to maintain homeostasis by preventing painful ideas, emotions and drives [22]. However, while the research suggests that men who utilize the above noted defenses often develop aggressive projective defensive configurations [22], for the participants in the current study, it appeared that they actively rejected the aggressive male stereotype and adopted the nurturing and stalwart protector role. Many of the participants described feelings that they needed to be a provider, ensure the wellbeing of others and give their all to their partner while neglecting their own needs.

Among the participants, various unconscious defensive styles ranging from immature to mature defensives presented themselves. However, the unconscious defense of “doing and undoing” was seen amongst participants when they found themselves under stress. The process of doing and undoing is a psychological defensive style that I conceptualize as the “fix it” mentality. That is to say that when our participants are undergoing some relationship stress, rather than attune to their partner they may unconscious misalign, realize the misalignment and engage in the process of trying to “fix” the problem at hand. As noted above, the blocking of awareness to vulnerable emotions may serve as a motivating force for this dynamic to play out. Research shows that within the psychological defense’s literature, their exists a gender difference. According to Noriega et al, psychological defenses and their use are tied to cultural upbringing [6]. Noriega et al argues that women are socialized to be submissive and utilized emotion focused problem solving where as men are socialized to be dominators that utilize problem solving focused defenses [6].

In a study by Bullitt and Farber, gender difference defensive styles were examined in the context of intimate relationships [23]. Bullitt and Farber argued that because males and females tend to identify with their parent of the same sex, that they would develop varying defensive styles [23]. While the use of mature defenses was observed in both genders, Bullitt and Farber found that men tended to use more intermediate forms of defensive styles [23]. This suggested that men oscillated between mature and immature psychological defensive in the contexts of their romantic relationships. Furthermore, their results showed that men tended to use primitive defenses such as regression [23]. Of course, it should be noted that the use of psychological defensive style was experience dependent, suggesting that those from alcoholic homes may indeed showcase primitive and immature defenses given their experience with chaos in the alcoholic home.

In a study by Maltby and Day, the relationship between forgiveness and defensive style was examined to ascertain the likelihood of positive forgiveness and absence of negative forgiveness regarding the type of defense utilized [24]. Maltby and Day found a negative relationship between neurotic defensive style and forgiveness suggesting that individuals who use neurotic defenses (Undoing, idealization, reaction formation) are less likely to forgive other people [24]. This finding suggests that men who grew up in an alcoholic home may indeed struggle to forgive their family, their partner and themselves for their own personal limitations. These finding give further detail in the picture of the codependent male from an alcoholic home. The literature suggests males under societal pressures to adopt highly masculine roles may also engage in, holding grudges, refusing to forgive yet fix the problems around him [24].

Parentification was described by Salvatore Minuchin as “the expectation that one or more children will fulfill a parental role in the family” [25]. The parentified child within the family system takes on undue responsibility for the emotional wellbeing of family members such that when family members are in distress this individual would console and comfort them [26]. Therefore, the child in the alcoholic home, would inevitably become parentified due to the necessity to control the chaos of the alcoholic family. In a study by Chase et al, they found that alcoholism and parentification are linked because of the accommodating roles that family members assume to protect and compensate for the alcoholic [27]. Furthermore, there were several detrimental effects on child development tied to the parentification and burdens assumed in fulfilling the parentified role [27]. For the participants it seemed that being parentified resulted in an intermediate defensive style wherein societal expectations of masculinity played a significant role in their ability to manage and navigate romantic relationships.

Difficulty Communicating One’s Needs

The struggle to communicate one’s needs within relationships can be a challenge for anyone navigating the intricacies of romantic relationships. Many interpersonal variables and life experiences affect the individual’s ability to communicate effectively with a romantic other. Therefore, one might infer that for a male who was raised in an alcoholic home and grappling with the social pressures to meet masculine gender roles, communication may prove to be a much greater challenge than normal. Participants in this study reported that some problems faced within their relationships included difficulty communicating their needs, withholding their opinions or taking steps to avoid confrontation which usually involved some communication breakdown.

Some factors that affect a male’s ability to effectively communicate with their partner may be linked to their biology. According to a study by Pennebaker and Roberts, they found that men use a peripheralist theory to perceive emotion whereas women use cognitive appraisal theory [28]. The peripheral theory by William James posits that perceiving emotions is based on the physiological changes within the body. The cognitive appraisal theory by Schachter and Singer posits that internal physiological cues are secondary and situational cues play a greater role in appraising and perceiving emotion [29]. According to Pennebaker and Roberts women presented as experts at reading and assessing situational cues accurately thus allowing for more effective communication styles [28]. Furthermore, women have been shown to be more sensitive to subtle situational cues relevant to emotion than men suggesting that women pay more attention to and are better decoders of emotion relevant facial and other non-verbal cues [28].

Given the research on varying communication styles between males and females, one might pose the question as to how these phenomena come about. From a societal perspective males and females undergo different learning experiences in understanding themselves and the world around them. The study found that participants highlighted that emotional expression was not encouraged within the alcoholic family system. Thus, the ability to effectively recognize and communicate their needs may have been compromised. Biologically males tend to rely on physical cues of emotion [28]. Therefore, recognizing emotion utilizing only physical cues proved to hinder male’s ability to effectively name and label the emotions felt.

Research supports that when individuals utilize negativedirect forms of communication where they are being coercive and demanding, negative outcomes are indicated [30]. In contrast, the research suggests that when individuals engage in positiveindirect communication strategies immediate perceptions of communication success were observed [30]. The participants in the study endorsed that when they try to communicate with their romantic other, they struggle because they try to avoid being overbearing or domineering. Many participants reported that they try to avoid stereotypical masculine roles and may tend toward more feminine nurturing roles. Perhaps our participants have learned in childhood that toxic masculinity was counter productive as a relationship model and therefore resist the societal pressures to meet masculine roles in favor of perceived “feminine” roles. Noriega et al argued that stereotypically “feminine submissiveness” was attributed to codependent behavior due to social pressure [6]. Therefore, it seems that when males interpret their codependent behaviors, they may label them as “feminine.” Teaching men to be aware of their internal reactions as well as recognizing the most effective way of communication may prove to be a favorable experience for those who lacked the appropriate modeling of communication in their youth.

Struggle in sexual aspects of relationships

Struggles in sexual aspects of relationships were observed in participant transcripts with many participants endorsing that they sought out women who were maternal by nature. While on the surface and inherently this is not a negative phenomenon, for the individual raised in an alcoholic home however it may serve to support codependent behaviors. According to Tobin, the maternal drive in women is natural and serves to bolster a sense of intimacy within the relationship [31]. However, within the male psyche there is a conflict in relating to their partner as a supportive lover vs. an erotic figure [31]. As this dynamic unfolds the relationship inevitably loses a sense of intimacy because males may begin to lose his sense of what it means to be a man in the relationship. Unconsciously the women become a surrogate mother thus allowing for the male’s codependent behaviors to become amplified.

According to Tobin, in the early stages of infancy an attachment bond forms between mother and child wherein the child reaches out for support, empathy and comfort [32]. Inevitably this attachment bond has its faults, but it is the “good enough” mother that supports the child’s attachment needs. When the caregiver does not reflect or meet the attachment needs of the child a narcissistic injury occurs where the child does not feel “seen,” validated or affirmed. It is the narcissistic injury that persists into the adult romantic relationship where the individual develops severe codependent character structures – thinking and believing what the other thinks and feels [32].

For the participants in this study, it appears that due to the unavailability of alcoholic caregivers to meet the healthy narcissistic needs of the child they in turn develop a codependent attachment style. Since alcoholic parentage appears to heavily influence how the codependent male relates to others it appears that in navigating romantic relationships the drive to seek out nurturing and supportive “maternal” like figures is strong.

Self-worth as defined by sexual dysfunction is a common issue faced by males in relationships. Due to the societal pressures of masculinity, individuals struggling in sexual aspects of relationship may exhibit distancing behaviors wherein males will begin restricting their emotions, experience embarrassment, and feel uncomfortable for having been vulnerable. In a study by Komlenac et al, it was found that masculine norms and sexuality is focused on the functionality of the penis [33]. When participants in their study experienced premature ejaculation or erectile dysfunction, Komlenac et al posited that due to a gender role conflict their ability to perform was negatively affected [33]. Consequently, males who are unable to emotionally express themselves may place greater value on sexual intimacy as a way to connect with one’s partner [33]. As such, because men likely learned maladaptive communication styles from alcoholic home, they may be unable to effectively communicate their intimacy needs to their partner in sexual struggles.

Difficult family upbringing

The findings of the study confirmed and validated the numerous deleterious effects an alcoholic home can have on an individual’s developmental and future intimate relationship trajectories. By and large participants in this study described experiences with loose boundaries in the home, alcoholism in the home and a chaotic environment that results from the alcoholism. The literature on alcoholism is vast and supports many of the experiences our participants have experienced namely that individuals from alcoholic homes often isolate, experience their own substance use/ abuse and have difficulty communicating their needs to others.

In a study by Tinnfält et al, children from an alcoholic home were interviewed to capture themes in their experience growing up in that environment [34]. Tinnfält et al found that children from alcoholic homes experiences deep sadness, tried to control situation in different ways, wished they could change the future, but retained a love for their parents despite the chaos around them [34]. The participants in the current study also reported several very difficult experiences in their household. However, despite the number of difficulties experienced in the household our participants appeared unable to provide a real representation of their parents such that their parents were either represented as all good or all bad. Theoretically this process is described through a borderline characterological lens as “splitting” where the individual splits their parental objects into all bad and all good due to attachment ruptures in the relationship. It seems that in adulthood the memories of their childhood remain but Tinnfält et al suggests that for these individuals to truly recover from their dysfunctional upbringing support should be offered [34]. Tinnfält et al suggests that group support, family support and when parents take responsibility for their abuse and accept treatment, proved to relieve the pressure face by children of alcoholics [34].

Clinical Implications

Clinically, the findings suggest that males from an alcoholic home who struggle in their ability to navigate romantic relationship need support. Based on the literature it is apparent that codependent males need outreach, assessment, and treatment to address their self-concept, their ability to connect with a romantic other and address their maladaptive coping styles. Conceptually it seems that codependent males struggle with the schematic core beliefs of unrelenting standards and approval seeking as presented by Dr. Jeffery Young.

One of the study’s finding suggested that codependent males tend to isolate themselves in response to stress. The study shed light on the fact that due to adverse childhood experience the learned method of coping was to take on the burden of responsibility and grit their teeth through the emotional pain which ultimately led to isolative behaviors. One method of addressing this struggle in codependent males would be to conduct outreach through similar methods used by alcoholics anonymous. The study illuminated the necessity for males to build healthy comradery in order to build healthy relationships with one another. This modality is useful especially for this population as it helps to reinforce that men from an alcoholic home are not alone in their experience. They can lean on one another and find healing in a special bond that may serve to propel their growth and recovery. Much like the AA model, men who participate in a men’s codependent group would be able to heal themselves by healing others. Literature shows that acts of service often provide the best form of self-healing, therefore, by incorporating outreach into the group structure codependent males should be able to build a network of support with one another.

Schema Therapy is the combination of cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal, experiential, and psychodynamic therapy [35]. For this population, this modality is an excellent fit for treatment given the myriad of adverse childhood experiences that have influenced how participants conceptualize the world around them. Schema therapy is the perfect means of addressing this group’s needs as it takes into consideration “universal core emotional needs” as the foundation for treatment. According to schema therapy universally individuals need safety, stability, nurturance, acceptance, autonomy, competence and a sense of identity [35]. The study illuminated that when males from an alcoholic home lack these universal needs they have a probability of developing codependency and maladaptive coping styles. Furthermore, it appears that participants sense of identity is affected by developing core schemas of unrelenting standards and approval seeking.

Approval seeking is the excessive emphasis on gaining approval, recognition, or attention from other people, or fitting in at the expense of developing a secure and true self [35]. It was found that study participants are focused on others in order to validate their performance whether that be from a romantic other or their parents. From an early age it seems that participants learned to disregard their true selves in order to meet the needs of an alcoholic parent or their partner in the future. According to schema therapy individuals with this core belief often make major life decisions that are inauthentic or unsatisfying, or in hypersensitivity to rejection [35]. This suggests that while study participants may feel like they are acting true to themselves, it appears they remain in a state of question who they really are and what they need to be the champion of their own life.

The Unrelenting Standards schema was prominent among our participants, so much so that it was categories as a theme for the study. This schema is characterized by the belief that one must strive to meet very high internalized standards of behavior and performance, usually to avoid criticism [35]. Several participants shared experiences that showcased the need to strive to be greater either for their partner or their parents at an early age. It seems this core belief develops out of the process of parentification. Due to misaligned role assignment within the family system participants felt the burden to become the parent to maintain homeostasis within the system. Ultimately, individuals with this core belief experience significant impairment in pleasure, relaxation, health, self-esteem, sense of accomplishment or satisfying relationship [35], all of which was endorsed by the sample.

The study’s findings illuminated some of the characterological features of a male struggling with codependency. Some of these features included a limited ability to tolerate distress, struggling with interpersonal effectiveness and splitting others into good objects and bad objects. Clinically these features have been well researched and the literature provides a myriad of intervention strategies in Dialectical Behavioral Therapy that would address the specific characterological traits that could potentially hold back the codependent males.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) was first developed by Marsha Linehan to address the unique needs of adult women diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder. One of the core tenants of DBT is a focus on achieving balance and a strong emphasis on acceptance [36]. For males struggling with codependency, the study showed that the root of many of the interpersonal difficulties lie in their past. The chaotic home environment during the formative years of their lives informed how they would navigate romantic relationships. As such by utilizing skills in DBT namely, mindfulness and distress tolerance, males struggling with codependency could navigate the stress of their relationships. Mindfulness in DBT teaches participants to retain a present moment focus and non-judgmentally accept the raw experience from an observer perspective [36]. Therefore, utilizing a present moment focus, rather than react to situations, codependent males could learn how to recognize their internal environment and respond accordingly. Acknowledging that distress cannot be changed and learning to either suppress or radically accept the distress may act as a first step toward codependent males developing openness to their own experience rather than fighting to control situations around them [37].

Once the individual becomes aware and mindful of their internal environment, interpersonal effectiveness is sure to follow. The male with codependency should in turn be able to recognize their emotions rendering them open to effectively assess the interpersonal stress they find themselves in. For example, rather than focusing solely on their own stress in an argument, they can instead practice mindfulness and become aware of their own position as well as their partner’s. Whereas before they may have been closed off to the experiences of others, focusing solely on the uncomfortable feelings within themselves, once they develop a position of openness, they effectively limit their reactivity and improve their interpersonal effectiveness [38]. The literature supports that by focusing on emotions from a present moment focused lens, individuals can develop a sense of sensitivity to emotion, increase awareness, and increase the capacity to tolerate emotion distress and decrease impulsivity [38]. Furthermore, by engaging in radical acceptance and mindfulness, literature shows that individuals develop non-judgmental acceptance in all aspects of their lives [38]. For the codependent males this process this would indicate that they can begin viewing their partners and thereby their parents as whole objects that are a mixture of good and bad. It is the development and attentional awareness that ushers this process into effect because the codependent male who had previously cut off their emotions now developed the ability to acknowledge and accept their position in the romantic relationship and the parentchild relationship from the past [37]. Overall, by engaging males with codependency in a process of radical acceptance, mindfulness and distress tolerance from a DBT standpoint, individuals can recover from their interpersonally traumatic backgrounds to live a fulfilling life.

Future Directions

The themes presented in this study brought to light several phenomena worth exploring for men who come from an alcoholic home. Namely the manner with which men are affected by alcoholism even when they are not seeking out romantic relationships. It would prove beneficial to the population to potential discover a character profile or specific personality type that lends itself to the development and maintenance of symptoms related to codependency. Furthermore, the methodology utilized to study this population.

Inherent within this study were several limitations. For one, the use of colleague referral and snow-ball sampling proved to be a challenge because of the limited availability of willing participants. Although efforts were made to address this limitation, future research may be able to incorporate a quantitative approach that allows individuals to fill out a survey from the privacy of their home. This approach would allow for anonymity and potentially garner a wider participant pool. Demographic considerations may be a limitation of our study as participants consisted of 3 while males and 3 Hispanic males. Future directions in the area of codependent males may choose to explore the cultural variability among males. This approach would benefit the literature base because it would allow for a more inclusive view of how various types of men from all walks of life experience the alcoholic home and romantic relationships. Furthermore, this study only explored the codependent heterosexual male which based on representation may prove to be a limitation. Future directions might consider how men from the LGBTQ+ community experience alcoholic environments and navigating romantic relationships from their perspective. Further exploration into how culture plays a role in the development of codependent symptomology should also be considered. However, future directions should be careful as to avoid pathologizing culturally normative experiences.

This study provides a foundation for the potential areas to explore within the experience of codependent males. Since this is a foundational study aiming to add to the literature base, future directions should consider branching out and including far more than, 6 participants. For the purposes of this study, 6 participants sufficed due to the groundbreaking nature of the study. However, it would prove beneficial for future directions to include a larger participant pool in order to potentially uncover unknow phenomena in the male experience. This study observed how codependent males navigate romantic relationships coming from an alcoholic home with alcoholic parentage. It might prove interesting to explore how codependent males’ function with an alcoholic partner. Since much of the literature base focuses on how codependent females function with alcoholic husbands, by observing the opposite, codependent males with alcoholic female partners, may prove to be worth exploring for the sake of adding to the literature. Expanding upon the research may prove to provide greater awareness into the potentially unique experiences that codependent men experience.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- Subby R (1988) Lost in the shuffle: The co-dependent reality. Deerfield Beach: Health Communications.

- Beattie M (1992) Codependent no more: How to stop controlling others and start caring for yourself (2nd edn). Hazelden Foundation, Center City, USA.

- George WH, La Marr J, Barrett K, McKinnon T (1999) Alcoholic parentage, self-labeling, and endorsement of ACOA-codependent traits. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 13(1): 39-48.

- Miller WR (1987) Adult cousins of alcoholics. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 1(1): 74-76.

- Beesley D, Stoltenberg CD (2002) Control, Attachment Style, and Relationship Satisfaction Among Adult Children of Alcoholics. Journal of Mental Health Counseling 24(4): 281.

- Noriega G, Ramos L, Medina-Mora M, Villa AR (2008) Prevalence of codependence in young women seeking primary health care and associated risk factors. Am J Orthopsychiatry 78(2): 199-210.

- Woodside M (1988) Research on Children of Alcoholics: past and future. Br J Addict 83(7): 785-792.

- Viorst J (1986) Necessary losses. Simon and Schuster, New York.

- Bowlby J (1958) The nature of the child's tie to his mother. Int J Psychoanal 39(5): 350-373.

- Smith JA, Osborn M (2015) Interpretative phenomenological analysis as a useful methodology for research on the lived experience of pain. Br J Pain 9(1): 41-42.

- West MO, Prinz RJ (1987) Parental alcoholism and childhood psychopathology. Psychol Bull 102(2): 204-218.

- Wells M, Glickauf-Hughes C, Jones R (1999) Codependency: A grassroots constructs relationship to shame-proneness, low self-esteem, and childhood parentification. American Journal of Family Therapy 27(1): 63-71.

- Cermak TL (1986) Johnson Institute Books professional series. Diagnosing and treating co-dependence: A guide for professionals who work with chemical dependents, their spouses and children. Johnson Institute Books.

- Young JE, Klosko JS, Weishaar ME (2007) Schema therapy: a practitioner’s guide. Guilford, New York.

- Overall NC, Fletcher GJO, Simpson JA (2006) Regulation processes in intimate relationships: The role of ideal standards. J Pers Soc Psychol 91(4): 662-685.

- Kannan D, Levitt HM (2013) A review of client self-criticism in psychotherapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration 23(2): 166-178.

- Leary MR, Tate EB, Adams CE, Batts Allen A, Hancock J (2007) Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. J Pers Soc Psychol 92(5): 887-904.

- Chassin L, Handley ED (2006) Parents and families as contexts for the development of substance use and substance use disorders. Psychol Addict Behav 20(2): 135-137.

- Miczo N (2004) Humor ability, unwillingness to communicate, loneliness, and perceived stress: testing a security theory. Communication Studies 55(2): 209-226.

- Lopez MF, Doremus-Fitzwater T, Becker HC (2011) Chronic social isolation and chronic variable stress during early development induce later elevated ethanol intake in adult C57BL/6J mice. Alcohol 45(4): 355-364.

- TEDx Talks (2016) The Mask of Masculinity – the traditional role of men is evolving: Connor Beaton TEDxStanleyPark.

- Mahalik JR, Cournoyer RJ, DeFranc W, Cherry M, Napolitano JM (1998). Men's gender role conflict and use of psychological defenses. Journal of Counseling Psychology 45(3): 247-255.

- Bullitt CW, Farber BA (2002) Gender differences in defensive style. J Am Acad Psychoanal 30(1): 35-51.

- Maltby J, Day L (2004) Forgiveness and defense style. J Genet Psychol 165(1): 99-109.

- Minuchin S (1974) Families and family therapy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- Byng-Hall J (2002) Relieving parentified children's burdens in families with insecure attachment patterns. Fam Process 41(3): 375-388.

- Chase ND, Deming MP, Wells MC (1998) Parentification, parental alcoholism, and academic status among young adults. American Journal of Family Therapy 26(2): 105-114.

- Pennebaker JW, Roberts T (1992) Toward a his and hers theory of emotion: Gender differences in visceral perception. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 11(3): 199-212.

- Schachter S, Singer J (1962) Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychol Rev 69(5): 379-399.

- Overall NC, Fletcher GJO, Simpson JA, Sibley CG (2009) Regulating partners in intimate relationships: The costs and benefits of different communication strategies. J Pers Soc Psychol 96(3): 620-639.

- Tobin J (2017) The "Maternalizing Dynamic" in romantic relationships.

- Tobin J (2019) The Shared Psychological Origin of Narcissistic and Codependent Relational Styles.

- Komlenac N, Siller H, Bliem HR, Hochleitner M (2019) Associations between gender role conflict, sexual dysfunctions, and male patients’ wish for physician–patient conversations about sexual health. Psychology of Men & Masculinities 20(3): 337-346.

- Tinnfält A, Fröding K, Larsson M, Dalal K (2018) I feel it in my heart when my parents fight: Experiences of 7–9-year-old children of alcoholics. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 35(5): 531-540.

- Rafaeli E, Bernstein DP, Young J (2010) Schema therapy: Distinctive features.

- Swales MA (2009) Dialectical behaviour therapy: Description, research and future directions. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy 5(2): 164-177.

- Holmes P, Georgescu S, Liles W (2006) Further delineating the applicability of acceptance and change to private responses: The example of dialectical behavior therapy. The Behavior Analyst Today 7(3): 311-324.

- Zeifman RJ, Boritz T, Barnhart R, Labrish C, McMain SF (2019) The independent roles of mindfulness and distress tolerance in treatment outcomes in dialectical behavior therapy skills training. Personal Disord 11(3): 181-190.

-

David Tolossa, Bina Parekh, Beatriz Lopez. A Qualitative Approach to Codependence in Men: Effects on Romantic Relationships. 4(4): 2021. OAJAP.MS.ID.000594.

Codependency; Addiction; Alcoholism; Romantic relationships, Unrelenting Standard, Maladaptive Coping, Adopting the Role of Protector, Struggle in Sexual Aspects of Relationships, Difficult Family Upbringing, Adult Children of Alcoholics

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.