Mini Review

Mini Review

A New Model of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Integrating Top-Down and Bottom-Up Processing for Understanding Obsessions and Compulsions

Harkin B* and Yates A

Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Manchester Metropolitan University, England, UK

Harkin B, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Manchester Metropolitan University, England, UK

Received Date: September 13, 2024; Published Date: November 08, 2024

Abstract

This review examines four research papers by the present authors [1-4] that advance understanding of the cognitive mechanisms underlying obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Building on this foundation, we propose a model that integrates top-down (cognitive control) and bottom-up (sensory processing) processes to explain the development and persistence of obsessions and compulsions. This model shifts the focus from domainspecific deficits to a broader perspective on how cognitive and perceptual interactions shape OCD symptoms. First, we present a framework centred on executive function, binding complexity, and memory load (EBL) to address inconsistencies in research findings on memory performance in OCD. Our work shows that while verbal memory is often intact, visuospatial memory is more frequently affected, shifting the focus from general memory performance or types of memory (e.g., visual vs. verbal) to a clearer view of how task content and cognitive demands influence memory outcomes. We further demonstrate the use of a multidimensional meta-analytic approach [2,3] to gain a more detailed understanding of memory performance in OCD, extending beyond previous findings in the literature. Specifically, we highlighted that central executive function was the determining factor in memory performance of those with OCD [2], and then in a finer grained analysis we identified the role of top down (maintenance and updating) and bottom-up processes (perceptual integration) in explaining the poorer memory of those with OCD [3]. Finally, we apply these insights to propose a new perspective on the roles of top-down and bottom-up functioning in the context of obsessions and compulsions in OCD.

Mini Review

Harkin and Kessler [6] first introduced a framework centered on executive function, binding complexity, and memory load (EBL) to explain inconsistencies in research findings on memory capacity in OCD. The EBL framework builds upon earlier studies [5-7], and other research [8], which suggest that memory impairments in OCD are secondary to deficits in executive function. The EBL model predicts that as the cognitive demands of memory tasks increase, individuals with OCD perform worse, with executive dysfunction being the primary driver of this decline. Building on this, Persson et al. [2] employed a novel multidimensional meta-analysis (mi-MA) approach to isolate moderators and examine the relationships within the EBL classification system. The method was predicted to highlight the complexity of OCD-related memory impairments and allow for a deeper investigation into the various cognitive factors influencing these deficits. Results revealed that the EBL model predicted memory performance, with larger memory impairment on visual tasks, compared with verbal tasks associated with greater demand on executive function; that is, as EBL demand increases, those with OCD performed progressively worse on memory tasks. This showed that memory performance was consistently identified as a key factor in the development and maintenance of OCD, indicating that executive function as key to understanding the memory performance of those with OCD.

However, despite extensive coverage of a relationship between memory performance and executive function in the OCD literature, the relative contributions of specific aspects of executive control have remained elusive. In a subsequent study, [3] extended the mi-MA approach with a more detailed multilevel meta-analysis, examining executive control through both top-down (e.g., attention control, maintenance, and planning) and bottom-up processes (e.g., perceptual integration). This analysis revealed that deficits in working memory maintenance, updating, and perceptual integration are key to understanding OCD-related memory impairments. In that, as top-down demands increased, individuals with OCD showed poorer memory compared to controls, with only maintenance and updating – rather than attentional control or planning – affecting memory performance. Similarly, in the bottomup model, as perceptual demands increased, memory declined for individuals with OCD, with perceptual integration – rather than salience – driving this effect.

Crucially, analyzing these dimensions within the top-down and bottom-up frameworks revealed a lack of significant contribution from the visual–verbal distinction. Specifically, executive function similarly showed nonsignificant differences between tasks of a visual or verbal nature, aligning with findings from our previous research. Furthermore, exploratory analyses indicated when comparing clinical and subclinical OCD participants, maintenance and updating (top-down) and perceptual integration (bottom-up) were the only significant predictors of memory performance in the clinical but not the subclinical OCD group.

Then in a fourth paper, Harkin and Yates [4] addresses inconsistencies in research on memory impairment in OCD. We argue that the traditional view, which focuses on domainspecific memory impairments (such as deficits in visuospatial versus verbal memory), may not fully capture the complexity of cognitive dysfunctions in OCD, in which they struggle with memory, attention, and self-regulation. Instead, memory impairments are secondary to broader deficits in executive function, particularly cognitive control, and attention modulation processes where there is a reduced ability to control competing external stimuli (sensory) and internal (cognitive) intrusive thoughts involving obsessions and compulsions [4].

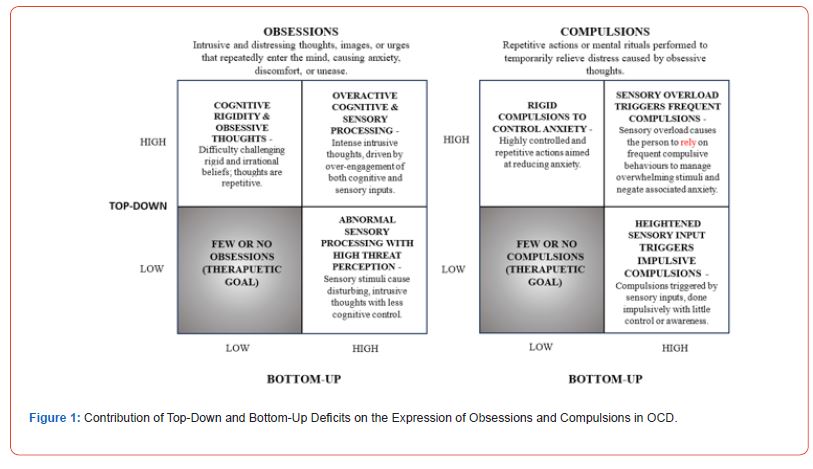

The intrusive thoughts typical of OCD can consume significant mental space, making it challenging to hold and manipulate other information in the mind. We propose that both top-down processes (e.g., attentional control, planning) and bottom-up processes (e.g., perceptual integration) play a significant role in memory deficits seen in individuals with OCD. The review concludes that a comprehensive model integrating these processes offers a more accurate understanding of OCD symptoms, supporting the idea that memory impairments in OCD are not isolated but are part of broader cognitive dysfunctions. Lastly, based on these findings and conclusions, we propose a novel model of OCD (Figure 1). This model incorporates both top-down (cognitive control) and bottom-up (sensory input) processing to explain the development and manifestation of obsessions and compulsions. More narrowly construed as a complex cognitive and attention control processes and highlights a significant role for interactions between highlevel top-down (attention control, maintenance and updating, planning) and bottom-up low-level sensory properties (perceptual integration, perceptual salience).

Attention itself is multifaceted and can be described via both top-down and bottom-up mechanisms, therefore, competitive interactions between attention and multisensory integration can often be complex and situation dependent in those with OCD. Hence individuals with a reduced ability to automatically and unconsciously disattend selectively to their own intrusive thoughts may therefore be vulnerable to developing OCD. For example, someone who struggles to automatically dismiss or ignore intrusive thoughts, such as persistent worries about contamination, may become fixated on these thoughts. Instead of unconsciously filtering them out like most people might, they focus on them, leading to repetitive behaviours like excessive handwashing, which can contribute to the development of OCD. The top-down dimension represents deficits in cognitive and attention control, such as impaired executive functioning, cognitive rigidity, and difficulty inhibiting intrusive thoughts, while the bottom-up dimension reflects the role of heightened sensory input and perceptual integration in triggering compulsive behaviours.

In summary, our findings emphasise the crucial role of executive functioning in memory performance among individuals with OCD. Through a detailed analysis of top-down and bottom-up processes, we uncover the distinct contributions of cognitive and attentional control, maintenance and updating, flexibility/planning, perceptual integration, and perceptual salience to memory outcomes. Notably, maintenance and updating emerge as key predictors within the top-down framework, while perceptual integration significantly impacts memory performance in the bottom-up model. These findings offer valuable insights into the intricate interplay between cognitive processes and memory deficits in OCD, which allowed us to identify novel targets for interventions targeting specific executive functions to enhance clinical outcomes. (Figure 1). The model illustrates how different combinations of these two processing pathways can lead to variations in OCD symptom expression. For instance, overactive cognitive-sensory processing, driven by heightened bottom-up input and reduced cognitive control, can result in intrusive obsessions, where patients struggle to suppress overwhelming sensory stimuli.

On the other hand, cognitive rigidity may be the result of impaired top-down control, leading to inflexible thinking patterns and repetitive compulsions aimed at reducing anxiety from obsessions. Furthermore, we also suggest that the model may potentially differentiate between those with checking versus washing symptoms. For example, it those with predominantly checking compulsions may be more influenced by top-down deficits (difficulty inhibiting checking behaviours), and those with washing compulsions may be more sensitive to heightened sensory input (e.g., tactile hypersensitivity or fear of contamination). A point that highlights the utility of our model to inform future research. Most important, our model identifies a region of optimal functioning (i.e., bottom left square – low bottom-up and top-down), which may provide a potential target and area to shift those with OCD towards. This model and conceptual space in terms of the differentiation between optimal and suboptimal functioning could guide more personalized treatment approaches in future research and clinical practice.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No Conflict of Interest.

References

- Harkin B, Miellet S, Kessler K (2012) What Checkers Actually Check: An Eye Tracking Study of Inhibitory Control and Working Memory. PLOS ONE 7(9): e44689.

- Persson S, Yates A J, Kessler K, Harkin B (2021) Modelling a Multi-Dimensional Model of Memory Performance in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Multi-Level Meta-Analytic Review. J Abnorm Psychol 130(4): 346-364.

- Harkin B, Persson S, Yates A J, Ainara Jauregi, Kessler K. (2023) Top-Down and Bottom-Up Contributions to Memory Performance in OCD: A Multilevel Meta-Analysis with Clinical Implications. J Psychopathol Clin Sci 132(4): 428-444.

- Harkin B, Yates A, (2024) From Cognitive Function to Treatment Efficacy in Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: Insights from a Multidimensional Meta-Analytic Approach. J Clin Med 7;13(16): 4629.

- Harkin B, Kessler K (2009) How Checking Breeds Doubt: Reduced Performance in a Simple Working Memory Task. Behaviour Research and Therapy 47(6): 504-512.

- Harkin B, Kessler K (2011) How Checking as a Cognitive Style Influences Working Memory Performance. Applied Cognitive Psychology 25(2) 219-228.

- Harkin B, Rutherford H, Kessler K (2011) Impaired Executive Functioning in Subclinical Compulsive Checking with Ecologically Valid Stimuli in a Working Memory Task. Front Psychol 2: 78.

- Greisberg S, McKay D (2003) Neuropsychology of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Review and Treatment Implications. Clin Psychol Rev 23(1): 95-117.

- Harkin B, Kessler K (2011) The Role of Working Memory in Compulsive Checking and OCD: A Systematic Classification of 58 experimental Findings. Clin Psychol Rev 31(6): 1004-1021.

-

Harkin B* and Yates A. A New Model of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Integrating Top-Down and Bottom-Up Processing for Understanding Obsessions and Compulsions. Open Access J Addict & Psychol 7(5): 2024. OAJAP.MS.ID.000674.

Pain patients; Drug therapy; Urine drug testing; Drugs; Pain medications; Rehabilitation centers; Pain/ortho; Pain management; Primary care pain; Internal medicine; Primary family medicine; Pain orthopedics; Physical medicine; Sports medicine

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.