Review Article

Review Article

What do the Figurines of ”Bird Ladies” in Predynastic Egypt represent?

Sven Ulrich Christiansen*

Oscar Pettifords Vej 25 1. Th 2450 Copenhagen SV, Denmark

Sven Ulrich Christiansen, Oscar Pettifords Vej 25 1. Th 2450 Copenhagen SV, Denmark

Received Date: March 07, 2023; Published Date: March 23, 2023

Abstract

My wonder was piqued when I read the Brooklyn Museum’s description regarding Figures 1a and 1b:” The bird-like faces on two of these figurines probably represent human noses, the source of the breath of life [1].” Immediately I would describe the head as “inhuman” and “flamingolike”, so why did specialists in the field interpret it so differently.

When I dived into the area, it turned out fortunately that in addition to these figurines, which I have chosen to call “Bird Ladies” after the nickname of the most famous, there were also several decorated jars depicting women with traditional faces but with raised hands and there was a tradition of seeing these in connection with the figurines. It provided a broader, faceted basis from which to discuss interpretations.

A better and enlarged image of a detail on a decorated jar showed reasonably clearly a woman with raised hands and a bird’s head (Figures 3 and 6) and it has also pulled me in a bird-like direction. I have arrived at the following hypothesis which reasonably covers the nine focus points / details I think an interpretation should answer: The Bird Ladies represents a hybrid between bird and woman - a goddess. The raised arms probably express resurrection. The goddess might be an early version of the white vulture goddess Nekhbet.

Keywords: Predynastic Egypt; Bird Lady; bird-like; figurine; Nekhbet

Introduction

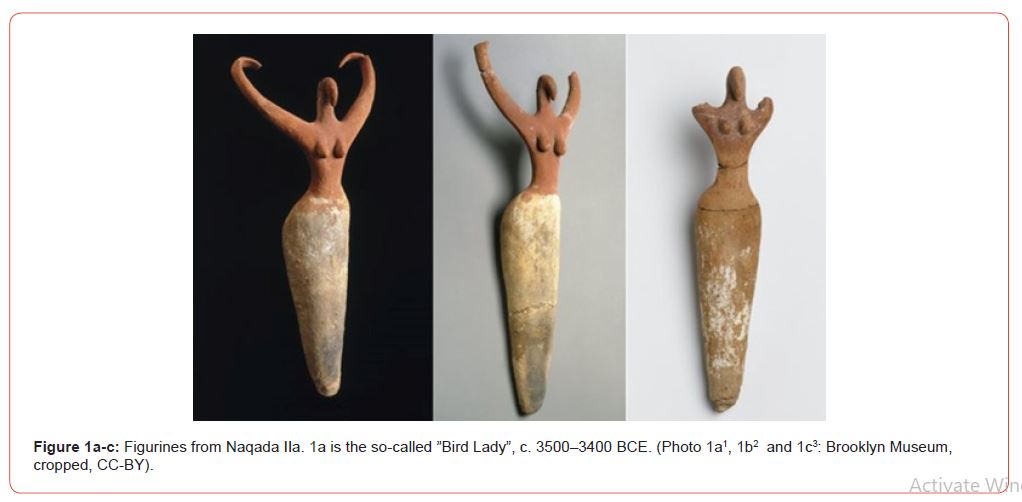

Figure 1 shows examples of figurines from Brooklyn Museum’s collection of Bird Ladies that are all approximately 5400 years old, meaning that they originate from predynastic Egypt. Predynastic is also prehistoric and Daniel [2] writes about this:” For the prehistoric period, which now appears to stretch from 2,000,000 years ago to about 3000 BCE, archaeological evidence is the only source of knowledge about human activities.”

Since there are no contemporary texts to relate to, analysis and argumentation will in the following largely be based on images of figurines, pottery, and the like, but of course on a basis of general trends in the predynastic period, but without texts the emphasis must be greater on what you can immediately observe.

To have a reasonably solid basis to assess interpretations on, I selected some focal points; three points regarding the appearance of the figurines, two points regarding the excavation of the figurines and four points based on the images on decorated jars. It can become a bit random if you interpret based on a single observed detail and many explanations can then seem equally good, but the coincidences should be reduced when the number of details that an interpretation must cover increases.

In the selection of points, I have emphasized details that are surprising, such as the forward-facing thumbs on the Bird Lady and therefore challenge an explanation – a detail that the interpretations often overlook.

The selected topics are initially described based on what can be immediately observed. The final interpretation should give reasonable answers to these essential features, and along the way they are used to valuate interpretations as less satisfactory if these only explain a few of these points.

In the selection of relevant findings, I have extensively used Patch [3] (ed), The Dawn of Egyptian Art. Central themes here is both figurines and the special gesture with the raised arms seen on decorated ware. I have largely taken the Met’s comprehensive exhibition catalog as my starting point.

In the selection of relevant findings, I have extensively used Patch [3] (ed), The Dawn of Egyptian Art. Central themes here is both figurines and the special gesture with the raised arms seen on decorated ware. I have largely taken the Met’s comprehensive exhibition catalog as my starting point.

A Descriptive Presentation of the Nine Selected Focal Points

A first description of the Bird Ladies

The figurines have a white-painted conical lower body and a faint marking of the separation between the legs, which are interpreted as the Bird Ladies wearing a white skirt - (Focus point 1), with no hint of feet. They have an unnaturally narrow waist, wide hips, and natural breasts.

Figure 1c’s arms are broken off, and Figure 1b’s hands are missing, but the fragments suggest that they were intended to be held in a position like Figure 1a. Figure 1a’s forearms are lifted above the head and turned 180 degrees so that the thumbs would point forward (if they were not broken off) - (Focus point 2) Needler [4] notes “ … with thumbs curiously to the front” and that it had a left thumb when found.

Needler [5] describes the head of the Bird Lady as follows: “The small birdlike head, devoid of facial features, curves continuously into the long neck.” - (Focus point 3). There are hints that some of the heads should have had black hair / a black wig.

The place of discovery

The figurines in Figure 1 were excavated at el Ma’mariya - (Focus point 4) by Henri de Morgan in two burials on a predynastic cemetery. (El Ma’mariya is located about 80 km south of Luxor, Upper Egypt).

Needler [6] describes the findings as follows from H. de Morgans Report:

Burial 2. Naqada II a. Flexed burial in oval grave; dimension of grave not given, except depth 1.50 m. (see field notebook).

Two ”B” vases, … Two ”small urns in coarse red clay,” … A ”small dish,”... Nubian decorated bowl, … Two terra-cotta female figures, [Figure 1a and Figure 1b] … Flint ”fishtail” knife, … … Burial 186 contained sixteen terra-cotta females figures [including Figure 1c]. Most of these are fragmentary; … Morgan found at least fifteen pottery vessels of various shapes in this grave, …

Although the grave goods are not as many as found in later graves, there is enough to establish that it must be given importance. - (Focus point 5).

The Bird Ladies and pottery in Naqada II.

Fortunately, the findings from Predynastic Egypt also includes several decorated wares. Although the heads of the figurine-like figures on the potteries are painted as traditional simplified heads seen from the front or back - and thus does not look like Bird ladies in this respect - the special raised-arms gesture match. I will therefore include these as a basis for the further interpretation.

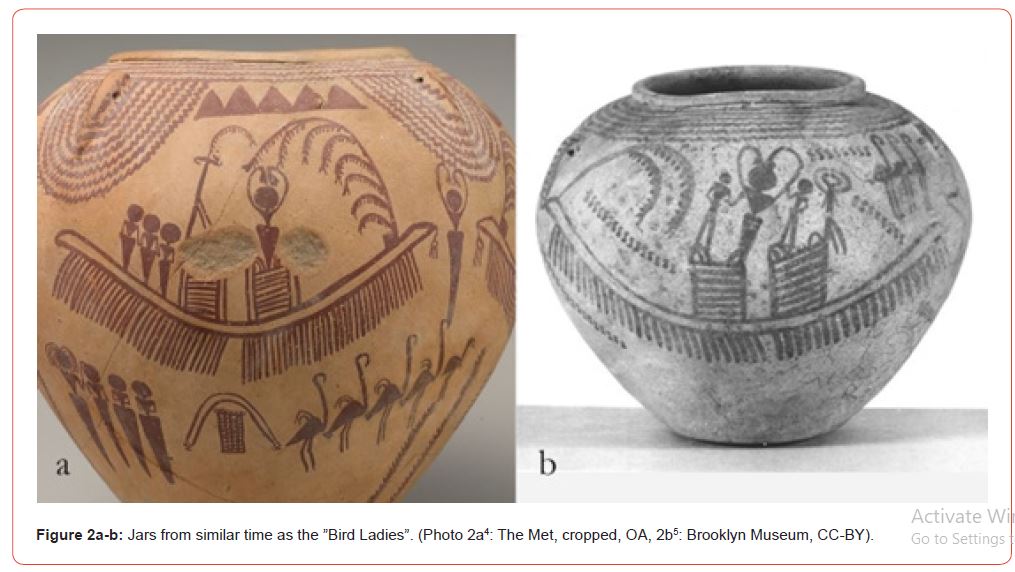

“The jar shown in Figure 2b is excavated near el Ma’mariya. The site of Figure 2a is not specified, and this unfortunately applies to most of the other jars showing women with the raised-arms gesture.

Looking at Figure 2, we find that the women with the special raised arms gesture stand out by being larger than the other people - (Focus point 6).

If you count the number of oars on the boats in Figure 2, there are 66 and 48 oars, respectively - and with oars on both sides, it must mean 132 and 96 rowers with one man per oar. (With one oar per 67 cm it gives lengths on 44 m and 32 m.) Although the oars are a decorative element, and the numbers should hardly be taken to be accurate it indicates that they must have been large ships with many oarsmen. On each jar three boats are depicted, each with its own standard, so a jar represents quite a good amount of people at that time, which points to that the decoration depicts a significant event - (Focus point 7).”

In addition to jars with boats, there are also jars primarily with animals, where ladies appear with the special raised arms gesture:

Foot Notes

1. https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/488773

2. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/4223

3. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/4224

4. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/545755

5. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/3276

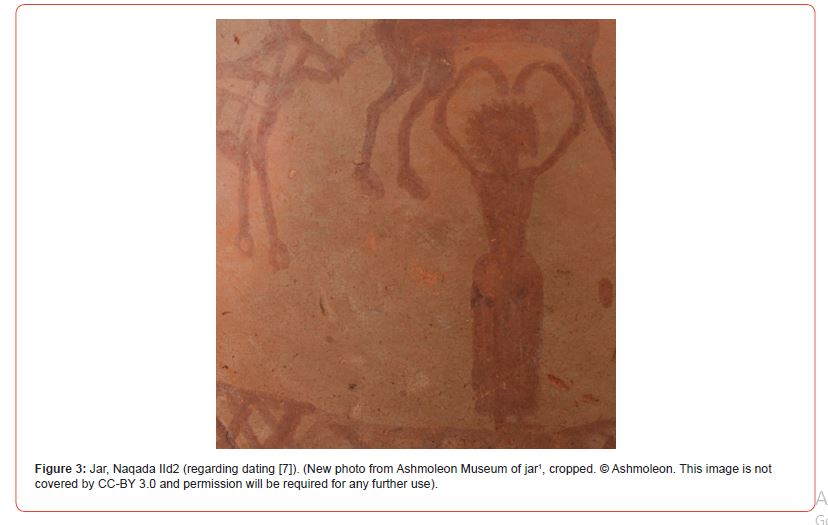

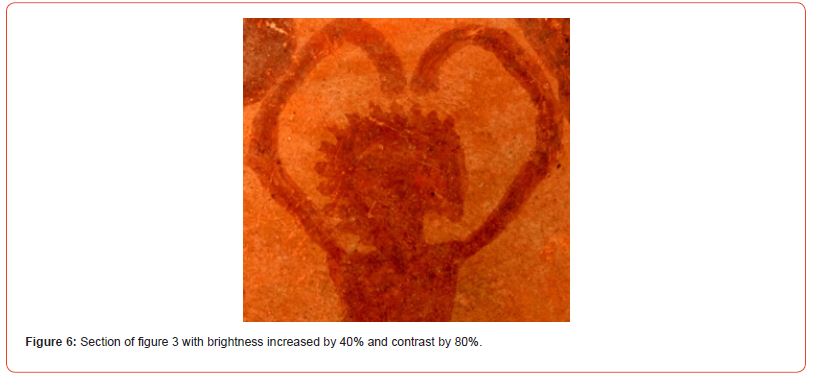

In Figure 3 the feet are seen from the side, the skirt is loose, the upper body is seen from the front, but the head also appears as seen from the side. This is a change from the previous i.e., There are developments and changes in the predynastic period - (Focus point 8).

The head of the figure in Figure 3 - (Focus point 9).

I have now presented the nine focus points that I will use in discussing the different interpretations. I have endeavored to only include points that can be directly verified by looking at the pottery, and regarding the excavation only to include points for which there is written documentation. Should I have included more material? I will discuss this in the following section.

A First Review of the Interpretations of the Basis Points

The Bird Ladies

Foot Notes

6 https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/488773

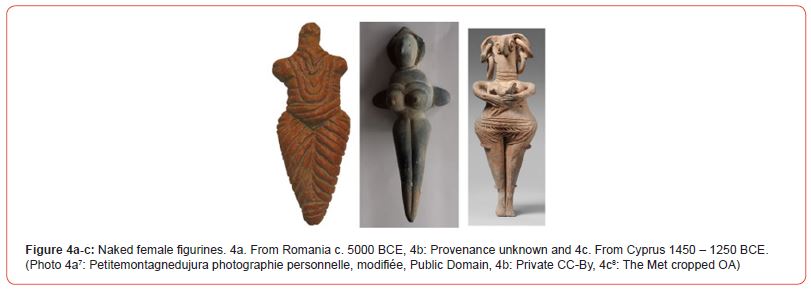

Figure 4 is included to provide a perspective beyond figurines from Egypt. Among other things to illustrate that the triangular lower body itself and the missing feet are not unusual at the time - almost the opposite. On the other hand, wearing a skirt is very unusual. Often the female gender is clearly marked as in Figure 4c. The arms are also often non-existent or close to the body. It is therefore unusual for the Bird Ladies to have distinctive raised arms, although this is also known from some other figurines. That the head looks alternative - sometimes bird-like - is not unusual.

See Patch about standing figurines made in the abbreviated style: body, arms, and head [8].

Point 1: The Bird Ladies wearing a white skirt

The surprising thing is that the Bird Ladies are not naked [9], indicating that the white skirt must have had a cultic significance. Patch [10] also notices the white skirt and sees a connection between the Bird Ladies and a Bowl with 8 women (c. 3700 BCE) - also with white clothes but with a more traditional bird-like faces / beak-like noses - from Abydos, about 140 km north of el Ma’mariya. However, these do not have raised hands but hold each other’s hands. But Fig. 2a also shows” cult women” who do not have raised hands. If we accept the connection with the Bowl with the 8 women, we move the start of the cult back about two hundred years to Naqada Ic and expands the geographic area of the cult. And at the same time, we must note that priestesses in the cult, when they are shaped in clay, can also have a bird-like face.

Patch [11] also mentions some fragments of decorated linen (Late Naqada II) from the Predynastic cemetery at Gebelein, about 40 km north of el Ma’mariya. Here there are both some with raised arms and some holding each other’s hands, and the torsos of the two with raised arms are larger than those of the others so they must have been particularly highlighted like the women with raised arms on the decorated jars. All apparently turn their backs to the viewer, and all have black hair / wear black wigs. There are two figures where the “lower part” can be seen. Both have their hands pointing down and both have a very long black rectangular “lower body” (not white and triangular). Is it a loose-fitting skirt or train or something else? If it is a skirt, the color can obviously sometimes also be black.

Point 2: The raised arms

There is no consensus about the interpretation of the raised arms, so the point is pushed to next section.

Point 3: The Bird Ladies special face

Although there are disagreements about this point, there is nevertheless an understanding that many refer to them as birdlike. Regarding standing figurines generally, most agree that many of these have bird-like faces / beak-like noses [12], but at the same time many believe that it is a coincidence and that these figurines are not bird-like hybrids, but purely human. Another point for discussion in the next section.

The place of discovery

Point 4: Excavated at el Ma’mariya.

El Ma’mariya, like other Egyptian cities at that time, is close to the Nile. At the same time, the city is very close to Nekhen (Hierakonpolis). Friedman [13] write:” At its peak, in about 3700–3400 BC, Hierakonpolis was one of the largest urban centers, if not the largest, in the Nile Valley.”

The neighboring town to Nekhen is Nekheb, now Elkab (about 20 km from el Ma’mariya). Hendrickx [14] : ”Scattered sherds … indicate that the earlier phases of the Nagada culture, and probably even the earliest one (Badarian), are also represented at Elkab.”

”The principal deities worshipped at Elkab were Nekhbet and Sobek. During the Old Kingdom Nekhbet’s cult was situated in the desert, where the goddess had a sanctuary. Later the cult moved into the Nile Valley, and it finally predominated over those of other deities.”

Point 5: The grave goods

When there is quite a lot of grave goods – including bowls and the like, it is reasonable to assume that they believed in an afterlife and that the grave goods were to help on the way to this new world – or help in this new world.

Ordynat [15] has studied Egyptian anthropomorphic objects from 3700–3300 BCE, including figurines, and observed the following. Figurines are extremely rare. They are found in less than one percent of the burials excavated from the predynastic period, so the use of figurines in tombs has not been a common form of burial custom. This, of course, makes it difficult to say something for sure about why a small minority has figurines in their tombs. They may have had personal significance for the deceased, but beyond that it is reasonable to assume that they also were supposed to help with what the other grave goods was needed for; help achieve a good afterlife for the deceased.

The pottery

Point 6: The women with the raised arms gesture are larger than the other people

Picture explanation in connection with Figure 2b [16]:” The three painted boats all include palm branches at the prow, what may be oars along the bottom, and two cabins on deck. Each cabin houses a female figure flanked by smaller males, possibly representing a goddess and her priests.”

Goddess can be understood literally as here we have the goddess. But since all priestesses in fig. 2a overall has the same appearance except for size and the gesture of the arms, it is more likely that we have a priestess who is at this moment perceived as the goddess, either as part of a ritual or that she is at this moment possessed by the goddess and the goddess is acting through her. Today, our relationship with religious magic is more lukewarm, but we still have, for example, in the Catholic communion, the perception that a miracle takes place here and that bread and wine literally become the body and blood of Jesus Christ.

Hassan [17]:” Figurines of women with raised arms, and representations of such women on pots, towering over men, suggest that female goddesses might have figured highly in the religious discourse at Nagada [Naqada] in late Predynastic times.”

And that may also be the reason why this motif later disappears.

The decorated pottery is also presumed to be part of the grave goods in various graves, and must be presumed, in addition to a personal angle – perhaps a gift from a chief or local king – to have a similar helping role on the journey towards the Egyptian paradise – later in history time referred to as the land to the west or Netherworld [18]. If we go forward over 1000 years, one will think of the god Osiris, the god of the dead, of the flood and of vegetation, as a god it was good to have with you in the grave.

“From the very beginning Osiris was also taken to be one of the very great vegetation gods. His death and immersion in the waters of the Nile, followed by his glorious resurrection, evoked on a mythical level the cycle of nature and its periodic renewal. Osiris, then, is the seed, which dies when buried in the ground, only to be born again a few months later when the shoot comes through bursting with new life. [19]”

But in Naqada II it was a female goddess which some chosen ones took with them to the grave.

Point 7: The decoration depicts a significant event.

Picture explanation in connection with Figure 2a [20]:” The images on this vessel represent important social or religious events …”

Since the ships have so many oarsmen, they are hardly merchant ships but military ships. Also, the fact that the boats have standards suggests a military angle. So, a jar with 3 ships constitutes a quite nice fleet at the time - and quite a strong demonstration of power. One must assume that it was an event that the local chieftain/king attended/participated in. Patch [21] shows images of a jar in which, in addition to the priestess/goddess with raised hands, there is also a male figure of the same size as the goddess (or see [22]). This could be the local king.

Point 8: There are developments and changes in the predynastic period

With Figure 3 the images approach the later traditional painted representation of important people, with the head and feet and lower legs seen from the side with one leg in front of the other as if moving, while the shoulders are normally seen from the front [23]. An intermediate step in the development where only the feet are seen from the side can be found at the Mediterranean Museum in Stockholm [24].

There is a development in the predynastic period in religion and culture. Bard [25]:” Archaeological evidence points to the origins of the state which emerged by the 1st Dynasty in the Nagada culture of Upper Egypt, where grave types, pottery and artifacts demonstrate an evolution of form from the Predynastic to the 1st Dynasty.”

Foot Notes

7 https://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venusfigurine#/media/Fil:Venus_Roumanie.png

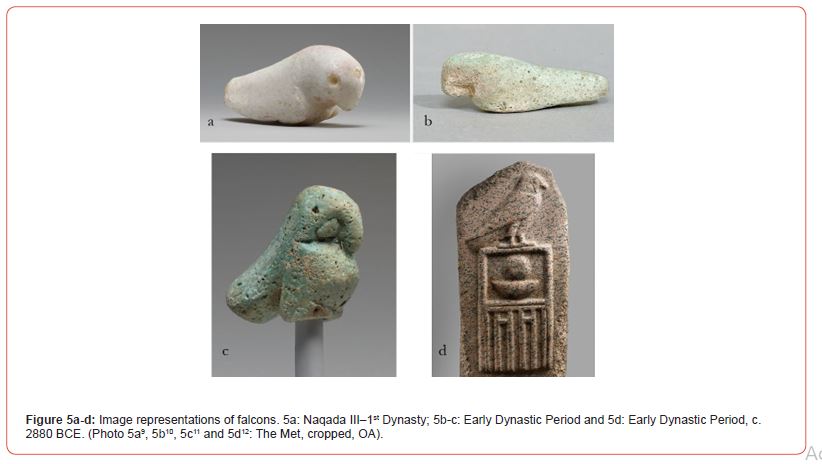

8 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/241098 9 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544902 10 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/547480 11 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/547473 12 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/545799Figure 5 is included to show that the development in the image description continues into the early dynastic period and at the same time to give examples of how different bird beaks can appear at this time. (In Nekhen/Hierakonpolis examples of falcons have been found as far back as early Naqada II [26]).

The image of falcons is influenced both by the perceptions of the various artists and by time. It is interesting that in the pre-dynastic and in the early dynastic period there is still room for local individuality. At the same time, we see a development with time, where the falcon in Figure 5d representing the god Horus brings us closer to the standardized falcons of later times.

One notices that all four beaks are very different. If you look only at the beaks, it could be four different birds. Figures 5a, 5b are examples of early depictions of falcons, where they are typically depicted horizontally in a hunting position. Later they are depicted sitting more diagonally [27].

If we consider Figures 5a, 5b and not least 5c we see a clear tendency to oversize the beaks.

The fact that there is a clear and significant development through the predynastic period means that we must be careful in drawing conclusions from texts 700–1100 years later.

Point 9: The head of the figure in Figure 3

The head on Figure 6 looks like a bird’s head, with an eye, a distinct beak and with feathers on all sides, e.g., an Egyptian vulture [28]. Their adult plumage is white, but with black feathers on the wings and tail. The image on the jar shows a hunting scene illustrated by the hunting dog and the wild animals and is interpreted as expressing order over chaos [29].

Review of the Points that have Particularly given Rise to Different Interpretations

Point 2: What do the raised arms represent?

Stevenson [30] relates the Bird Ladies to a group ritual and estimates that it must have been widespread, i.e., that a larger group of people at that time knew how the special gesture with the raised hands should be symbolically understood.

Ordinat [31] undergoes different interpretations of the raised arms. There are quite a few supporters that they should illustrate horns on cattle. Cattle were an important part of predynastic agriculture, and the bull is a classic symbol of power and fertility. The goddess could then be Hathor, which was depicted as a cow or as a woman with a sun disc and horns. As a goddess of fertility and goddess of death, she could fulfill points 5,6 and 7, but she is not related to anything bird-like, which could explain the special head of the Bird ladies – point 3.

It also does not provide a convincing explanation for the thumbs and the position of the hands does not correspond at all to the lyreshaped horns with the sun disc [32].

Horns can of course look different. Hendrickx [33] points out that “the double-horn”-standards in Figure 2b could be a human figure with raised arms. On the decorated pottery (Figures 2 & 3) form arms and hands almost a heart shape, which is not an obvious way to depict horns. Should the standards refer to the goddess to whom the raised hands refer, all the ships should have the same standard. Leemann [34] refers to a total of 32 different standards and concludes that there is disagreement about what they represent.

Otherwise, the arms are understood as representing woman arms with no explanation for the outward facing thumbs. The gesture itself is then understood as part of a dance or a ritual there e.g., expresses praise, greeting or rejoicing [35].

Another angle:

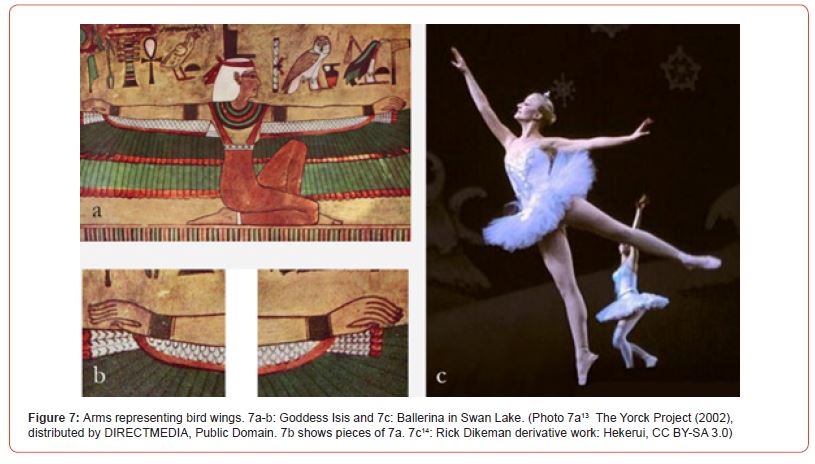

If you try to make the special gesture yourself with your head over your arms and thumbs forward, you can consider when you have done this movement - if ever. A similar movement is known from breaststroke swimming, but it is also used if one wants to illustrate bird wings. If we want an interpretation that explains the forward-facing thumbs and the bird-like heads, then the simple one is that the arms should represent wings. (Since they have fingers, the arms are of course a kind of symbolic wings).

Point 3: The Bird Ladies special face

Needler [36] writes:” It is possible that the bird likes head of our modeled figures are merely abstractions of human heads dictated by the limitation of the plastic clay or by superstitious fear of representing individuals ….”

Patch [37]:” Technical considerations, moreover, do not seem to have played a part in such abstractions …”

And the artisans’ possible limited abilities are also in a different context been commented by Hendrickx [38]:” It is quite obvious that these artisans were capable of producing almost any kind of representation desired. Therefore, if a representation is stylized, it should be regarded as intentional.”

”Superstitious fear of representing individuals” - although not particularly well known later from historical times, it may play a role. The figures on the decorated pottery are primarily round heads without facial features, and the figures on the previously mentioned linen are all seen from the back. But the natural thing would be to make something spherical and faceless as Venus of Willendorf. And it does not at all explain why bird-like faces are chosen for the Bird Ladies and many other figurines.

Bleiberg [39] writes about the Bird Lady:” This figurine depicts a woman with a birdlike face or wearing a mask with a bird’s beak. Such figures could have represented goddesses or priestesses who were part of the funeral procession”. There is no doubt about the bird-like feature here.

Stevenson [40] has no problem referring to them as bird-headed figurines. That some people see a nose and not a beak is mentioned without going into the problem further.

Brooklyn Museum [41] comment on a male figurine from Naqada:” … and the white paint on the male’s head and shoulders represent hair, also a human trait” - without pointing out that the face has clear raptor-like features.

Museum of Fine Art Boston [42] writes about a female figurine from Basileia: ”Female figure depicted with a narrow waist, broad hips and upraised arms. The head is beaked; however, this is likely due to abstraction rather than an association with a bird”. But this does not explain why bird-like faces are chosen as abstractions.

Foot Notes

13 https://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isis#/media/Fil:%C3%84gyptischer_Maler_um_1360_v._Chr._001.jpg

14 https://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/Svanes%C3%B8en#/media/Fil:Ballerina-icon.jpg

Brooklyn Museum [43] states about the female figurines:” The bird-like faces … probably represent human noses, the source of the breath of life”. The same interpretation can be found in Patch [44].

Point 7: A significant event

The raised arms also raise a question about what is happening on the decorated jars. Patch [45]:”The most widely agreed upon interpretation is that these individuals are enacting a ritual in which dance is the focus of the activity.”

However, Patch immediately points out that there are no dancing movements with the feet, as is otherwise the case with later known dance scenes from the Old Kingdom.

I agree that they likely portray a ritual, a ceremony, or a religious event. Probably a mythic tale unfolds. Religious events are often accompanied by song and music, and it is very likely that there have been rhythmic instruments such as clappers and that dance has been included. Dance can be used to enter a trance and thereby become one with the goddess, but dance does not explain why the priestess is particularly emphasized.

Another angle:

The large boats are likely sailing on the Nile, Egypt’s great river, so it is obvious to search for a suitably large event related to the Nile. Vanhulle [46] sees both boats as an expression of a hierarchical social order and as symbols of power that can ensure order in chaos - so likely an event where chaos could threaten: The Nile Flood.

Friedman [47]:” …the coming of the Nile Flood (the annual inundation) and with it the new year, an especially chaotic moment in the cosmic cycle of renewal that required extraordinary powers to negotiate.”

Patch [48]:” …then perhaps we should consider that they are carrying out a ritual involving the entire landscape.”

But the dominant figure – more important than the king’s fleet – is the priestess/goddess with the raised arms. She probably had the same role that Osiris later gets: to secure the cosmic cycle of renewal. Goddesses associated with the cycle of the year most often associated with fertility, death, and rebirth / resurrection (summer, winter, spring).

Hassan [49]:” Scenes on the pottery (Decorated class) may symbolize the duality of death and the notion of resurrection.”

Needler [50]: The Brooklyn figures with raised arms and birdlike head are perhaps to be considered supernatural beings; they may be identified with very similar figures appearing on the “D” pottery, where they generally dominate male companions, and it has been plausibly suggested that they are symbols of resurrection (H.-W. Mueller 1970 no. 4). [Mueller [51] is captivated by the strong and simplified expression of the figure and remarks:” Möglicherweise handelt es sich um ein Sinnbild der Auferstehung.” - It may be a symbol of the resurrection.]

If we look at Figure 2a there are both men who take part in the ritual and women with their hands in a more traditional position. Since the women with the raised hands are larger than the others, they must form the high point of the ritual, where the priestess becomes one with the goddess, the most important moment in the ritual. If we think of bird wings, the high raised wings must be when the bird takes off and must have air under the wings. And then the raised ”wings” could be an expression of the resurrection: the bird takes off and rises into the sky. And this would also make sense in funeral contexts.

Since the jars of known origin come from graves, it is natural to consider whether the people depicted on the jars should have something special to do with burials or that the ships themselves should have a significance in a funerary context [52]. But what can you really conclude from the fact that they were found in graves? We must assume that it is the elite who have been able to get hold of these decorated jars. And the elite - in older times - typically surround themselves with elite symbols of power even when they were buried. The boats could then be understood as a symbol of probably royal power / order in chaos [53,54] and the goddess could add power for resurrection.

Strudwick [55]: “Decorated pottery is rare and is found mainly in high-status burials … as similar motifs are also known from desert rock art, the message may be much broader, with motifs forming part of a graphic vocabulary ensuring fertility and rebirth, whether for humans or the cosmos.”

An Attempt at a Unifying Interpretation

The figurines represent a goddess – point 6, 7 and 5.

Point 6: The women with the raised arms gesture are larger than the other people. Since she is prominently featured, she must be something special. Her attitude does not suggest a person of power, a queen, so it must be that she represent a goddess. And if one accepts the connection between the Bird Ladies and the women with the raised arms on the decorated pottery, then the Bird Ladies must represent the same goddess.

In advance, there is no reason to exclude some goddesses at that time from being able to fulfill point 7: A significant event, regardless of whether one is thinking here of the Nile Flood or maintaining order in chaos in the wild nature. At the same time, a goddess linked to nature, creation or the renewal and resurrection of the world will fit nicely in funeral contexts - point 5. Ordinat [56] writes: ”The primary four goddesses who have been put forward as being represented in an earlier form in these female figurines are Hathor, Nut, Isis and Nephthys.”

As previously mentioned, Hathor has, among other things, the problem that she is not related to birds. However, it is the other three who strike out their wings protectively on the images of jewellery from among others Tutankhamun’s tomb [57] - and as Isis also does in Figure 7a. All three also make good sense in funerary contexts.

The figurines are part bird – point 2, 3 and 9

As previously mentioned, an interpretation of the raised arms as representing bird wings could explain point 2: the forward-facing thumbs. Now let’s take a closer look at point 3: “The small bird like head, devoid of facial features, curves continuously into the long neck.”. A human head has a fairly short neck. Then a large round/ oval head and finally a relatively small and short nose, while many birds have a long slender neck followed by a relatively small head and a long beak. It is not only a question of nose or beak, but also of neck and head. The head of the Bird Ladies does not look like human heads but fits much better with the neck, head, and beak of certain birds.

There are indications that they have had black hair/wig. It must have looked colorful with the red body, the white skirt, and a black wig. However, it is no more unusual than that a seated figurine, from roughly the same period (Late Naqada II) also has black hair / wig and a bird-like beak / beak-like nose [58]. Stevenson [59] mentions four examples of figurines with hints of hair.

Then there is point 9: The head of the figure in figure 3. I think it clearly looks like a bird’s head. But if it is a goddess with a bird’s head, then it must probably be the same goddess which was then associated with the other highlighted figures with raised hands and with the Bird ladies.

Nekhbet – point 4, 8 and 1

Point 4: Excavated at el Ma’mariya. Since the women with raised arms on jars probably represent a goddess, “the Bird Ladies” probably also represent a goddess. As a working title, we can describe her in Egyptian fashion as ”She of el Ma’mariya”. Patch [60] points out that it is likely that those who owned the Bird Ladies had a local cultic role, i.e., that there was a cult for She of el Ma’mariya in el Ma’mariya.

The decorated jars with boats indicate a large local cult event that must have involved the population of the nearest towns in the local area. Watterson [61]:” In Ancient Egypt, the basis of religion was not belief but cult, particularly the local cult which meant more to the individual.”

None of the four goddesses are known to be the Nome goddess of the area later [62], so I will introduce a goddess that fulfills this: Nekhbet: She of Nekheb, where Nekheb is close to el Ma’mariya. I will try to argue that She of el Ma’mariya is or later becomes Nekhbet.

Watterson [63] points out a development in the religion of the Egyptians starting with animism (” certain animals, birds, trees, or stones as homes for spirits”) and fetishism. Over time, they choose to anthropomorphize their animal deities. They do this in such a way that they keep the animal heads but at the same time equip them with a human body.

Later they depict gods in full human form, but still attached to an animal.

Finally, the Ancient Egyptians also value cosmic gods, but Watterson assesses:” Cosmic gods [as Nut and Re] were not fully developed until the historic era (post 3000).”

Foot Notes

15 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/559850

16 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544206

If we are to assess depictions of animal gods in terms of age in the era from 4000 BCE to 3000 BCE, it starts with that the animal is depicted directly, as is known for example from figurines of scorpions or falcons [64]. Then the animal appears in human form, but still with an animal head - which could be the case for “the Bird Ladies” and the goddess in Figure 3.

Roth [65] places the development of hybrid gods to the Early Dynastic period:” … anthropomorphic divinities were a later development, perhaps owing to the growing association of humans leaders with animals through their names …”. There may be a point in that when you disregard birds, but the many figurines with birdlike heads are hybrids. And what else should one call the lady from Figure 3. One must have associated these hybrid forms with something magical and related them to bird spirits/bird deities.

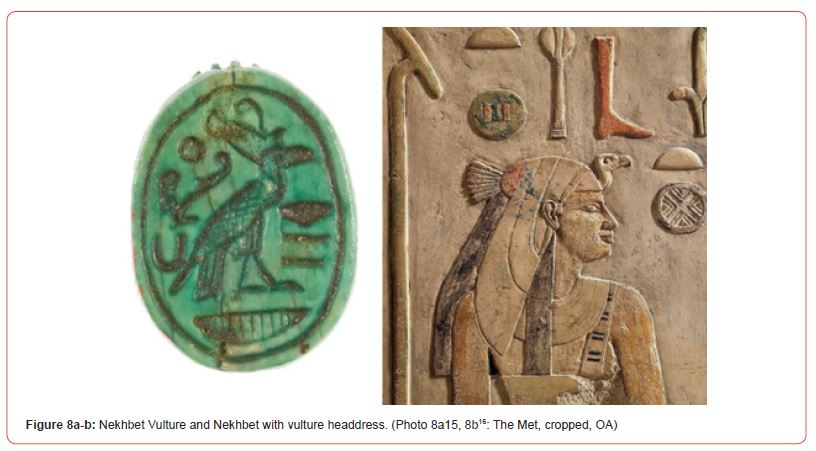

Nekhbet is a vulture goddess in the prehistoric way that she is most often depicted as a vulture and her attributes are those that the Egyptians associated with vultures. Among other things, vultures are linked to motherhood (the hieroglyph for mother is a vulture [66] and they stand for protection in the afterlife [67]. And vultures, which eats the dead bodies and flies up into the sky and create new vultures, new life, are clear illustrations of the continuous renewal of life, and a hope for the deceased for resurrection in the afterlife. Finally, vultures like other birds can function as a messenger between our world and the spirit world [68]. Altogether a very useful helper in the tomb.

She must have had a significant cult because she is named as the goddess of Upper Egypt and appears together with the goddess of Lower Egypt as “the two ladies” (a vulture and a cobra) on a tablet found in a mastaba at Naqada dated to first Dynasty, King Aha [69] c. 3100 BCE [70].

Watterson [71]: ”Nekhbet … became the principal goddess of Upper Egypt during the predynastic period.”

This fact that the royal power embraces her and makes her both a goddess of Upper Egypt and a king goddess [72] could be a classic way to get support from the cult’s priests and priestesses and the goddess’ followers in general.

Although Nekhbet is not as well-known today as, for example, Hathor, Nut, Isis, and Nephthys, as a vulture she is a favorite motif on the royal jewellery [73] both alone, together with Wadjet as the two ladies and hovering protectively with outstretched wings.

Nekhebet [Nekhbet] was part of the primeval cosmogonic traditions and symbolized nature and childbirth. … Her cult dated to the earliest periods of Egyptian history. … Nekhebet played a role in the saga of Osiris and inhabited the primeval abyss, nun, the waters of chaos before creation. In this capacity she was revered as a patroness of nature and creation [74].

The Goddess Nekhbet is from the 5th and 6th Dynasties portrayed both as a vulture and as a woman with a vulture headdress [75].

From the end of 5th Dynasty there exists a text, where Nut is placed as the mother of Osiris, Isis, Seth, Nephthys, and Thoth [76]. But it is difficult to trace Isis back to prehistoric times.

Point 1: The white skirt. The ancient Egyptians believed that all vultures were female [77] as males and females look quite similar - and therefore that they reproduced by parthenogenesis/virgin births. So, one reason for the skirts could be that it was a virgin cult? Since the two men in Figure 2b apparently do not wear skirts, they must either simply be helpers or the requirement to wear skirts only applies to the sect’s priestesses.

The color white is particularly linked to Nekhbet

“Nekhebet The white vulture goddess ... She was also depicted as a woman with a vulture headdress and a white crown. A longstemmed flower, a water lily with a serpent entwined, was her symbol ...She was also addressed as the Great White Cow of Nekheb [78].”

And she was known as the White One of Nekhen [79]. ”Die Weiße von Nechen” [80].

Although Nekhbet is referred to as the white vulture goddess, she is later depicted as a vulture quite colorfully.

Conclusion

The requirements to fulfill points 5,6 and 7 can be boiled down to the women with the raised arms representing a goddess.

The requirements to fulfill points 2, 3 and 9 can be briefly formulated as that the goddess must be a bird goddess.

To distinguish between priestesses and the goddess, I have emphasized the following objective points: Contiguous groups of two or more may represent priestesses. The special gesture with the raised arms shows that the figurine/image at this moment represents the goddess, and if it also has a bird-like head, I estimate that the figurine/image has been understood as an image of the goddess.

The simplest explanation seems to be that the Bird Ladies are a divine hybrid of bird and human, which I name: She of el Ma’mariya. Also, the woman in Fig. 3 seems quite clearly to be a bird-headed goddess.

As the goddess as She of el Ma’mariya could be an early version of I point to Nekhbet. She has clear connections to prehistoric times and have later in historical time a large cult very close to el Ma’mariya and the name Nekhbet: She of Nekheb suggests that she has been associated with Nekheb near el Ma’mariya for a long time before. As the White Vulture Goddess, she covers both the white color of the skirts and the bird-like appearance that could very well be inspired by a vulture.

If we consider the decorated jars, I see a double theme: To both renew life and at the same time maintain the good order of life in the face of chaos. In funeral contexts, renewal becomes resurrection in a new world, and the resurrection of life - both concerning nature and the dead - could be what one tries to capture in the ritual with the raised arms/wings.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflict of Interest

The individual photos indicate how they may be used.

References

- Brooklyn Museum n.d (2022) Female Figure [” Bird Lady”], (object 4225).

- Daniel GE n.d. (2022) “Britannica/archaeology/Interpretation”.

- Patch DC (ed) (2012) The Dawn of Egyptian Art. Exhibition catalogue. The Met, New York.

- Needler Winifred (1984) Predynastic Egypt and Archaic Egypt in the Brooklyn Museum. Wilbour Monographs (IX). The Brooklyn Museum, New York, pp. 336.

- Needler (1984) (see note 4), pp. 336.

- Needler (1984) (see note 4), pp. 90-91.

- Patch (2012) (see note 3), pp. 74-75.

- Patch (2012) (see note 3), pp. 103-110.

- Patch (2012) (see note 3), pp. 113.

- Patch (2012) (see note 3), pp. 115.

- Patch (2012) (see note 3), pp. 114.

- Patch (2012) (see note 3), pp. 110-113.

- Friedman R (2012) Hierankonpolis” in Patch DC (eds.), 2012. The Dawn of Egyptian Art. The Met, New York, pp. 82-93.

- Hendrickx S (2005) ”Elkab” in Bard, K. A. 2005. Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Taylor & Francis e-Library, pp 342-343.

- Ordynat R (2018) Egyptian Predynastic Anthropomorphic Objects: A study of their function and significance in Predynastic burial customs.

- Brooklyn Museum n.d. (2022) Jar with Boat Designs, (object 3276).

- Hassan FA (2005) “Nagada (Naqada)” in Bard KA 2005. Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Taylor & Francis e-Library, pp. 669-672.

- Bleiberg E (2008) To live forever: Egyptian treasures from the Brooklyn Museum. Exhibition catalogue. Brooklyn Museum, New York 26: 70-72.

- Grimal P (1965) Larousse World Mythology. Paul Hamlyn, London, pp. 36.

- The Met n.d. (2022) “Decorated Ware Jar Depicting Ungulates and Boats with Human Figures”, (object 545755).

- Patch (2012) (see note 3), pp. 72-73.

- The British Museum (2006) Jar, (object Y_EA35502).

- Nina de Garis Davies (2017) Ramesses III and Prince Amenherkhepeshef before Hathor.

- Carlotta (2009) Jar, (object 3006200).

- Bard KA (2005) Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Taylor & Francis e-Library, pp. 29.

- Hendrickx S, Friedman R, Eyckerman M (2011) Early Falcons. In: Morenz L, Kuhn R (Eds.), Vorspann oder formative Phase? Ägypten und der Vordere Orient 3500-2700 v. Chr.: Philippika, pp. 129-162.

- Hendrickx S, Eyckerman M, Föster F (2008) 'Late Predynastic Falcons on a boat' in Journal of the Serbian Archaelogical Society, pp. 371-384.

- VCF n.d (2021) Egyptian Vulture.

- Hendrickx S (2011) Hunting and social complexity in Predynastic Egypt. In: Bulletin des Séances Mededelingen der Zittingen, pp. 237-263.

- Stevenson A (2017) Predynastic Egyptian Figurines. in Insoll T (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Figurines, Oxford, pp. 63-84.

- Ordynat R (2013) The Female Form: Examining the Function of Predynastic Female Figurines from the Badarian to the Late Naqada II Periods. Honours Thesis, Monash University, USA, pp. 25-30.

- Nina de Garis Davies (1881-1965) Ramesses III and Prince Amenherkhepeshef before Hathor. New Kingdom, Ramesside.

- Hendrickx S (2002) “Bovines in Egyptian Predynastic and Early Dynastic iconography” in Hassan, F.A. (Eds.), Droughts, Food and Culture. Ecological Change and Food Security in Africa’s Later Prehistory, New York, pp.275-318.

- Leeman D (2019) An overview of the Predynastic Pottery of Ancient Egypt, Self-published, pp. 325-334.

- Patch (2012) (See note 3), 77-113.

- Needler (1984) (See note 4), 337.

- Patch (2012) (See note 3), pp. 103.

- Hendrickx S (2002) Bovines in Egyptian Predynastic and Early Dynastic iconography. In: Hassan F A (Eds.), Droughts, Food and Culture. Ecological Change and Food Security in Africa’s Later Prehistory, pp. 275–318.

- Bleiberg E (2008) To live forever: Egyptian treasures from the Brooklyn Museum. Exhibition catalogue. Brooklyn Museum, New York, pp. 71.

- Stevenson A (2017) Predynastic Egyptian Figurines. In: Insoll T (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Figurines, Oxford, pp. 63-84.

- Brooklyn Museum “Figure of a Man”, (object 44886).

- Museum of Fine Art Boston n.d. “Female figurines”, (object 130728).

- Brooklyn Museum n.d. “Female Figure [” Bird Lady”]”, (object 4225).

- Patch (2012) (See note 3), 103.

- Patch (2012) (See note 3), 74.

- Vanhulle D (2018) Boat Symbolism in Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt: An Ethno-Archaeological Approach. In: Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 17(1): 173-187.

- Friedman R (2012) Hierankonpolis. In: Patch, D C (Eds.), The Dawn of Egyptian Art. The Met. New York, pp. 82-93.

- Patch (2012) (See note 3), 77.

- Hassan F A (2005) Nagada (Naqada). In: Bard K A (Eds.), Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, Routledge, pp. 669-672.

- Needler (1984) (See note 4), 337.

- Mueller HW (1970) Aegyptische Kunst. Edited by Harald Busch. Umschau Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, comments to [Figure: 4].

- Hendrickx S, Eyckerman M (2010) Continuity and change in the visual representations of Predynastic Egypt. In: Raffaele F, Nuzzolo M, Incordino I (Eds.), Recent discoveries and latest researches in Egyptology. Proceedings of the First Neapolitan Congress of Egyptology. Naples, June 18th-20th, 2008 Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 121-144.

- Vanhulle D (2018) Boat Symbolism in Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt: An Ethno-Archaeological Approach. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 17(1): 173-187.

- Hendrickx S, Eyckerman M (2010) Continuity and change in the visual representations of Predynastic Egypt. In: Raffaele F, Nuzzolo M, Incordino I (Eds.), Recent discoveries and latest research in Egyptology. Proceedings of the First Neapolitan Congress of Egyptology. Naples 18-20 June 2008: 121-44. Wiesbaden, pp. 133.

- Strudwick N (2006) Masterpieces of Ancient Egypt, London, pp. 28-29.

- Ordynat R (2013) The Female Form: Examining the Function of Predynastic Female Figurines from the Badarian to the Late Naqada II Periods. Honours Thesis, Monash University, USA, pp. 28.

- Vilimkova M (1969) Egyptian Jewelery. Paul Hamlyn, London [Figures: 42,43,74].

- The Met n.d, “Figurine of a Seated Woman”, (object 547202).

- Stevenson A (2017) Predynastic Egyptian Figurines. In: Insoll T (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Figurines, Oxford, pp. 63-84.

- Patch (2012) (see note 3), 115.

- Watterson B (1984) The gods of ancient Egypt. New York, pp. 25.

- Hart, G. 2005. The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses. Routledg, pp. 117-122.

- Watterson B (1984) The gods of ancient Egypt. New York, pp. 32-33.

- Friedman R (2012) Hierankonpolis. In: Patch (Eds.), The Dawn of Egyptian Art. The Met. New York, pp. 82-93.

- Roth A M (2012) Objects, Animals, Humans, and Hybrids: The Evolution of Early Egyptian Representations of the Divine. In: Patch, D. C. (Eds.), The Dawn of Egyptian Art. The Met. New York, pp: 194-202.

- Kozloff A P, Bailleul LeSuer, R (2012) Pharaoh Was a Good Egg, but Whose Egg Was He?. In: Between Heaven and Earth: Birds in Ancient Egypt. Exhibition catalogue. Oriental Institute Museum Publications, Chicago, pp. 59-64.

- Bailleul LeSuer R (2012) Between Heaven and Earth: Birds in Ancient Egypt. Exhibition catalogue. Oriental Institute Museum Publications, Chicago, pp. 201.

- Bailleul Le Suer R (2012) University College, pp.16.

- (2001) University College London.

- Patch (2012) (See note 3), 214.

- Watterson B (1984) The gods of ancient Egypt. New York, pp. 135.

- Bonnet H (2005) Reallexikon der ägyptischen Religionsgeschichte. Hamburg, pp. 507.

- Vilimkova M (1969) Egyptian Jewelery. Paul Hamlyn, London, Figures [9, 10, 28, 32, 34, 45, 51].

- The complete gods and goddesses of ancient egypt. Internet Archive, pp. 274.

- El Shamy S, Hassan O I T, Al Arab, W S (2019) Goddess Nekhbet Scenes on Royal Monuments during the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties. International Journal of Heritage, Tourism and Hospitality, Egypt 13(1): 190-201.

- Hart G (2005) The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses. Routledge, pp. 115.

- Bonnet H (2005) Reallexikon der ägyptischen Religionsgeschichte. Hamburg, pp. 210-211.

- The complete gods and goddesses of ancient egypt. Internet Archive, pp. 274.

- Watterson B (1984) The gods of ancient Egypt. New York, pp. 136.

- Bonnet H (2005) Reallexikon der ägyptischen Religionsgeschichte. Hamburg, pp. 507.

-

Sven Ulrich Christiansen*. What do the Figurines of ”Bird Ladies” in Predynastic Egypt represent?. Open Access J Arch & Anthropol. 4(2): 2023. OAJAA.MS.ID.000584.

-

Brooklyn Museum's, Flamingo-like, Inhuman, Bird Ladies, Lower body

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- A Descriptive Presentation of the Nine Selected Focal Points

- A First Review of the Interpretations of the Basis Points

- Review of the Points that have Particularly given Rise to Different Interpretations

- An Attempt at a Unifying Interpretation

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

- References