Mini Review

Mini Review

The Nurnet Geoportal an Example oof Participatory Gis: A Review after Six Years

Roberto Demontis*, Eva Lorrai and Laura Muscas

CRS4 (Centro di ricerca, Sviluppo e Studi Superiori in Sardegna), Pula (Cagliari), Italy

Roberto Demontis, CRS4 (Center for Advanced Studies, Research and Development in Sardinia), Loc. Piscina Manna, Ed. 1-Polaris - 09050 Pula (Cagliari), Italy.

Received Date: October 21, 2020; Published Date: October 28, 2020

Abstract

A cultural heritage landscape is a defined geographical area that may have been modified by human activity and identified as having cultural heritage value by a community. In this field CRS4, by means of GIS, developed the Nurnet Geoportal (http://nurnet.crs4.it/nurnetgeo/) to manage and share information about the Bronze Age in Sardinia (Italy), identified in the Pre-Nuragic (3200−2700 BC) and Nuragic (up to the 2nd century AD) culture. The idea of a geoportal, based on webgis and crowdsourcing, was born in the beginning of 2014 at the Nurnet Foundation (http://www. nurnet.it). The Geoportal, fed by a net of conventional social connections or through social web networks empowered by private citizens, agents and public administrations sharing the same goals and interests, enables the users to access and share information about the ‘nuraghes’. A ‘nuraghe’ is the typical Sardinian building from the Bronze Age. The article shows the results of the project after six years.

Keywords: Cultural heritage landscape, WebGIS, Crowdsourcing, Partecipatory GIS

Introduction

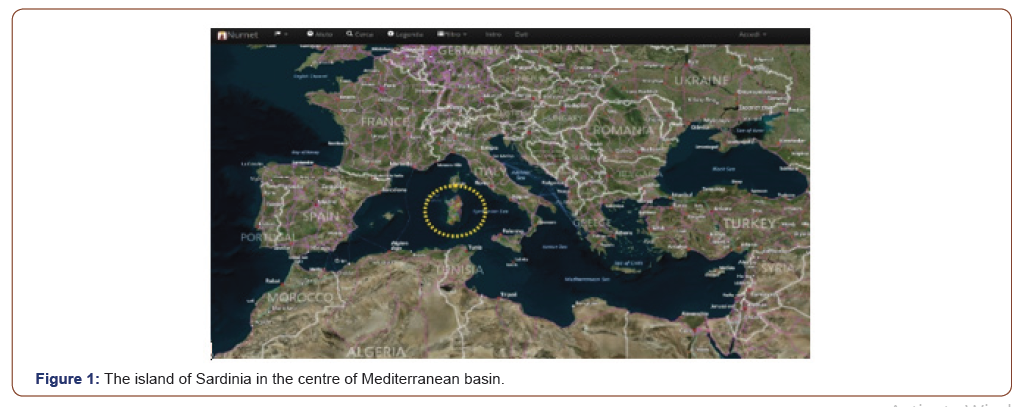

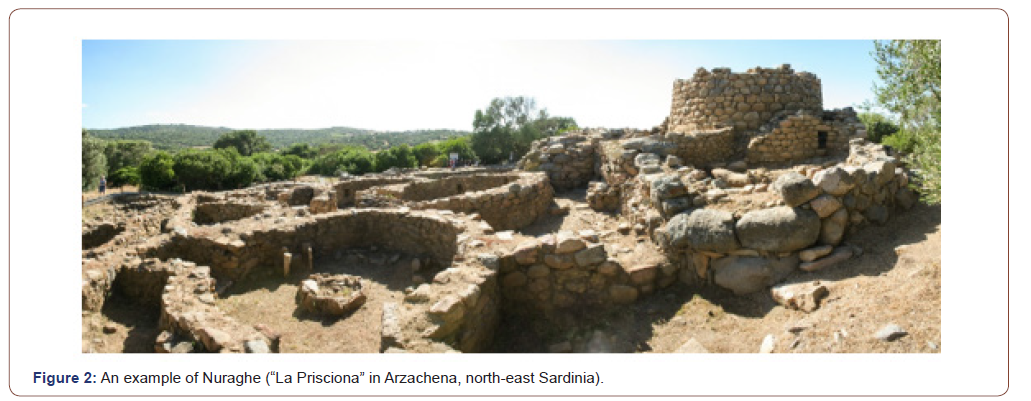

The Nuragic civilization developed in Sardinia (Figure 1) from the Bronze Age (18th century BC) to the 2nd century AD. The name comes from the most distinctive expression of their architecture, the tower-fortresses, ‘nuraghes’ (Figure 2). It is estimated that there are about 8000 Nuraghes, but not all are recorded, more than 2400 Domus de Janas (literally “house of the fairies”, pre-Nuragic chamber tombs), more than 50 holy wells, 800 giants’ graves, more than 300 menhirs, and 78 dolmens Lilliu [1] (Figure 1).

The various archaeological surveys documented since Taramelli in the beginning of the 1900’s, often in paper form alone, are not organized in databases and, in accordance with the standards for interoperability (standard such as CIDOC-CRM), not usable. The use of digital map libraries and the so called ‘geo-portals’ as tools for the conservation of cultural heritage is relatively new Karabegovic et al. [2] but it is already giving positive results, demonstrating the multiple advantages of the Web Map Services (WMS). Archaeological sites are often located in rural areas far from urban centres, hard to be maintained and sometime inaccessible due to poor infrastructure.

The use of WebGIS and crowdsourcing for research is a new practice, but it is gaining in popularity given the facility in collecting and cross-checking data Ballatore and Bertolotto [3]; McCall et al. [4]. It has been shown to be extremely useful in monitoring processing in several fields: vegetation cover, collecting and recording local names for rural areas Rampl [5], promoting environmental awareness and change Spanu et al. [6], and providing timely data that may otherwise be unavailable to policy makers in soil and water conservation management Werts et al. [7] (Figure 2).

Through WebGIS and crowdsourcing therefore it is possible to collect detailed information about what is called “cultural landscape”, testifying to those places that represent the “combined works of nature and of man” WHC [8] and embracing a diversity of manifestations of the interactions between humankind and our natural environment. Information collection from local people is needed, in order to record the history and memory of the traditional cultural landscapes WHC [9]. This cooperation between the two sets of actors, experts and local citizens, leads to another key point that is also one of the key statements of the project: the cultural identity of the local people, which is a component of cultural heritage and its protection. Indeed, while they are helping in the process of information collection, the local participants can rediscover their own roots and keep alive their cultural heritage, cultural landscape and memory (McCall et al. 2015), also making it available to younger generations. Consequently, the preservation and the monitoring of the historical sites will benefit from citizens cooperation

The Nurnet Geoportal

The idea of a geoportal was born in the beginning of 2014. After a first stage of data collection and project design, it was implemented and published on-line in June 2014. The interest that this instrument generated was immediate, thanks also to the Nurnet Foundation activities. This indicates that participatory solutions benefit from the direct involvement in data management of local people, local organizations and visitors.

The creation of the geoportal Nurnet aimed at several goals: having available a more accurate database of the Nuragic archaeological sites of Sardinia, simplifying the retrieving of internet information concerning this topic, promoting the strength of Participatory GIS (PGIS) and Crowdsourcing and, thanks to all these aspects, providing local governments with a concrete base on which to plan and set up activities to protect and promote the historical heritage, and improve services for tourists and visitors in general.

The Nurnet Geoportal is accessible via the web and it is based on webGIS and PGIS technologies. Through the portal it is possible to visualize, to select and to see information about all the elements in the map; authorized users can also modify the current information and add new elements (such as nuraghes, menhirs, the Sardinian megalithic gallery grave called giant’s graves, etc.). It is distributed with Creative Commons Attribuzione 4.0 Internazionale Licence. The implementation of the Nurnet geoportal is consistent with the “Open source” philosophy: the software used to create the geoportal is open source, and the published data are open data, available via open services.

The choice of the “Open” philosophy comes from the choice of Participatory GIS as the engine of the Geoportal.

The participation of local people and visitors in making and sharing the knowledge implies an open infrastructure that is able to involve a large number of people so as to ensure a significant data set. Applying an “open philosophy” approach by itself does not guarantee the quality of the data, and for this reason, the data item entered by the users in the portal - users are also editors - are validated by an expert before being published. The validation mechanism is similar to that used in Wikipedia for instance, though somewhat more restrictive.

In the realization of the Geoportal, special attention has been placed on the mechanisms and instruments for data publishing. Firstly, the Nurnet API was created for data sharing and management, the Geoserver (www.geoserver.org ), an Open GIS Consortium (OGC) Web Service Compliant application, has been added thereafter. Obviously, all the available data have metadata describing their genealogy and properties. An example of the use of Geoportal data in mobile device is the “Nurnet Map” App developed for Android environment. The App can be found in Google Play Store.

Conclusion

After the first year of activities, Nurnet Geoportal was joined by 96 editors of content, 15 validators and about 5000 sites to be verified and documented. After six year the Geoportal has only ten editors and 2 validators but now it includes verified and geo referenced data about 5136 Nuraghes, 700 of wich complex nuraghes, 774 domus de janas (literally “house of the fairies”, pre- Nuragic chamber tombs), 67 holy wells, 524 giants’ graves, 115 menhirs, 273 villages, 125 unicum and 47 tafons’ caves. About 2000 sites have textual documentation, photos and links to videos. The number of daily data users is around 1000, with peak of 1800 and more in periods near festivals.

At present, there are several Regional Services or other public or private companies that use the geoportal as datasource, as, for example, the services of the “Assesorato per il tursimo, artigianato e commercio” of Sardinia Region or the project “Sardinia project” promoted by the Business School Lausanne.

Even though it is based on open source software, nevertheless the system costs, both in terms of financial resources and in terms of people with appropriate skills and able to manage it. In order to guarantee the long- term sustainability of the project it is necessary to consider some forms of support. The main cost is the maintenance of the portal that requires specific technical competencies. The sustainability of the Nurnet Geoportal was initially guaranteed by voluntary work and by research activities while now it has some sponsors like “Fondazione Sardegna”. It is clear that a web solution with a discreet favour (successful application of web services) would have some intrinsic potentials if it was possible to apply analytic tools similar to Google analytics. In this way, the users’ data requests or selections, indicate an interest to a specific archaeological site of Nuragic and pre-Nuragic period.

Future works may include providing more than one language for the textual descriptions and the implementation of a statistical tool, a sort of decision support system, to help the managers of archeological sites to diagnose the attractiveness of a site, the changes over time, and comparisons with managed and unmanaged sites.

The obtained results highlight that the participatory process is a bottom-up approach: it is linked to a local territory and to an issue realized through the direct involvement of local NGOs in the data management. They could use the data in order to promote a sustainable tourism in all the sites that aroused interest from an archaeological point of view. It is also very important to detect where the tourist attractions are not easily accessible to people Demontis et al. [10]. This approach gives positive results in terms of quantity and quality of the data, and in terms of involving the local population in the production of the data, and thus helping to empower them.

The methodology employed is flexible and replicable for other territories and for other topics. Finally the Geoportal can be managed in a cloud environment at a relatively low cost. Its success in terms of user access can generate a lot of useful information for the analysis of tourism flows and for regional spatial economic management.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Lilliu, G (2006) Sardegna Nuragica, Appunti di Archeologia, Edizioni Maestrali, Nuoro, Italy, p. 25-33.

- Karabegovic A, Ponjavic M (2012) Geoportal as decision support system with spatial data warehouse. Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems (FedCSIS), IEEE, Poland, pp. 915- 918.

- Ballatore A, Bertolotto M (2011) Semantically enriching VGI in support of implicit feedback analysis. In Web and Wireless Geographical Information Systems. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, pp. 78-93.

- McCall M. K, Martinez J, Verplanke J (2015) Shifting boundaries of Volunteered Geographic Information systems and modalities: Learning from PGIS. ACME An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 14(3): 791-826.

- Rampl G (2014) Crowdsourcing and GIS-based Methods in a Field Name survey in Tyrol (Austria), United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names, Working Paper NO. 16/9, Twenty-eight session, , Item 9 of the Provisional Agenda Activities relating to the Working Group on Toponymic Data Files and Gazetteers.

- Spanu V, Gaprindashvili G, McCall M K (2015) Participatory Methods in the Georgian Caucasus: Understanding Vulnerability and Response to Debrisflow International Journal of Geosciences 6(7): 666-674.

- Werts J D, Mikhailova E A, Post C J, Sharp J L (2012) An integrated WebGIS framework for volunteered geographic information and social media in soil and water conservation. Environmental management 49(4): 816-832.

- United Nations Group on Geographical Names- Romano- Hellenic Division (2015) International scientific symposium, Place names as intangible cultural heritage, Firenze - Italy.

- World Heritage Convention (1972) Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage Adopted by the General Conference, 17th session, Paris, p. 16.

- Demontis R, Lorrai E B, Muscas L, DeMarr M, Estabrook S (2013) Cost function for route accessibility with a focus on disabled people confined to a wheelchair: the TOURRENIA Project. 29th Urban Data Management Symposium, London, p. 7-13.

-

Roberto Demontis, Eva Lorrai, Laura Muscas. The Nurnet Geoportal an Example oof Participatory Gis: A Review after Six Years. Open Access J Arch & Anthropol. 2(5): 2020. OAJAA.MS.ID.000549.

-

CIDOC-CRM; Cultural heritage; Cultural landscape and memory; GIS Consortium

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.