Research Article

Research Article

The Neoconservative School in U.S. Foreign Policy: Still A Valid Option in Defining America’s Role in the World?

Hafedh Gharbi, University of Sousse, Tunisia.

Received Date: May 19, 2023; Published Date: July 05, 2023

Introduction

The Neoconservative movement has been one of the most vibrant schools in U.S. Foreign Policy prevailing in the last 50 years. Intellectually fertile, politically astute and ideologically loaded, it has had a powerful impact on different Republican administrations, notably Ronald Reagan’s, George W. Bush’s and, though to a certain extent, Donald Trump’s. The object of this paper is threefold: to identify the Neoconservative movement, to locate it within the American Foreign Policy tradition and recent history, and to measure its capacity of adaptation to new challenges. The rationale of this paper is to evaluate the Neoconservative movement and demonstrate that it is still a valid school in International Relations, able to offer clear solutions to complex issues.

The Essence of Neoconservatism

Neoconservatism is often identified as yet another branch of the American conservative movement in general. This claim is only true to a certain measure: If Neoconservatism is indeed close to the ideological lines that have long governed the Republican Party and the conservative spectrum in general, it would be reductive and misleading to consider Neoconservatism as just another type of generic conservatism. In fact, the points of division between the two currents are numerous. For example, it can be assumed that Neocons have historically focused their Foreign Policy attention on the Middle- East, while the Cold War has had a major impact on classical conservative thought, defining and shaping its world vision for decades. In addition, Neocons hold an obsession with a few Foreign Policy tenets and principles, which classical conservatives disregard. For example, the principle of preemption, the rejection of social engineering after military interventions, and the firm belief in unilateralism at the expense of multilateral international cooperation. Those preferences have ascribed on the Neocon movement a reputation of hawkishness, aggression and warmongering.

One of the most distinguished neoconservative thinkers, Irving Kristol, refers to Neoconservatism as a ‘persuasion’ rather than a ‘movement’:

It is not a movement. Neoconservatism is what the late historian of the Jacksonian era, Marvin Meyers, called a ‘persuasion’, one that manifests itself over time, but erratically, and one whose meaning we clearly glimpse only in retrospect. Viewed thus, one can say that the historical task and political purpose of Neoconservatism would seem to be this: to control the Republican Party and American conservatism in general, into a new kind of conservative politics suitable to govern a modern democracy. (qtd. in Stelzer 33)

Irving Kristol is recognized as one of the spearheads of the Neocon ‘persuasion’ mainly through his articles and publications in different political journals starting from the 1960s. To many, he is a godfather of the movement. His definition here clearly points at the ambitious design of the Neoconservative school to become a dominant actor of the Republican scene, and to take over the platform by imposing its discourse at the political and executive levels.

Jonah Goldberg attempts another approach to define the ‘persuasion’: “Neoconservatism is not a mass- movement (…). One writer noted that Neoconservatism had no ‘common manifesto, credo, religion, anthem, flag or secret handshake” (Goldberg, 22). It is tempting, therefore, to claim that actually, Neoconservatism is no clear construct at the political level. Rather, it is an intersection of centrifugal forces with points in common; the arch goes from media pundits and journalists proliferating in magazines such as the Public Interest, Commentary, the National Review and especially the Weekly Standard, to academic and intellectual references such as Francis Fukuyama and Samuel Huntington, to career politicians such as John Bolton and Paul Wolfowitz. Rather than weakening the movement, this diversity has been able to express itself in different episodes with a single voice, de facto promoting what has come to be known as Neocon ideology and implementing it within different Republican administrations too.

Studies about the Neoconservative movement clearly point out at one important fact: they are “ex- leftists mugged by reality” as Kristol famously put it; they were liberal intellectuals driven away from Communism and its authoritarianism in the mid- twentieth century and transformed into its staunchest opponents, embracing instead the very American creeds of Liberalism and especially the championing of democracy. They developed a constant belief in an endorsement of social progress and the universality of human rights, which has earned them the labeling of ‘Idealist Wilsonians” in reference to the former American president’s 14 points in the Versailles Treaty, promoting the universality of these principles.

The Neoconservative movement has been vocal for decades, and politically active too. In addition to the magazines cited abovewhich were their favorite agoras to advance their positions on different issues- the Neocons have also been present and influential in many Washington and New York think tanks (Cato Institute, Heritage Foundation and American Enterprise Institute especially). This presence allowed them direct access to the highest spheres of decision- making in the White House and in Congress. They were also part of the Reagan administration, significantly contributing in the shaping of the administration’s policies in the last years of the Cold War. The Neocons interpreted the end of the five- decade long war with the Soviets, with Fukuyama as their most prominent speaker, as the triumph of their way of doing Foreign Policy. As the first generation of Neocons came from pro- Communist circles, they prided themselves in being pioneers in warning about the dangers of Communism and therefore considered themselves to be on the right side of history. During the Clinton years, they lurked behind the liberal internationalism of the epoch, then gained momentum again after 9- 11 as they seized the chance to direct the Bush administrations in its War against Terror, providing it with the ideological tools and principles for its action first in Afghanistan then especially in Iraq.

To recapitulate, Neoconservatism is a philosophical movement with clear political ambitions (to reach decision- making positions within the Republican Party and the administration). With time and experience, it has developed into an identifiable and reliable Foreign Policy school.

Neocons and the end of the Cold War: Nesting in the Reagan administration

The final years of the Cold War offered the Neoconservative movement in the U.S. momentum, exposition, and a reason of being.

The Neocons were essentially ex- leftists who abandoned the Democratic Party in the 1960s as they rejected the party line on the question of Israel, mainly. Supportive of the Zionist state in its warring endeavors and military operations, the Neocons saw in Israel a perfect exemplification of their Wilsonian Idealist worldview. They considered it an island of democracy in a sea of hostile countries, and therefore stood by it in their publications and analyses. This particular tenet remains, until now, a milestone of Neocon ideology.

The first major political breakthrough of the Neocon movement occurred in 1980, during the presidential election, as they championed Ronald Reagan. Kristol has the point:

It is not a movement. Neoconservatism is what the late historian of the Jacksonian era, Marvin Meyers, called a ‘persuasion’, one that manifests itself over time, but erratically, and one whose meaning we clearly glimpse only in retrospect. Viewed thus, one can say that the historical task and political purpose of Neoconservatism would seem to be this: to control the Republican Party and American conservatism in general, into a new kind of conservative politics suitable to govern a modern democracy. (qtd. in Stelzer 33) Reagan’s anti- conformist profile made him a suitable candidate to endorse at least part of the Neoconservative program and allow them access to positions of power. After all, he ‘owed them’ politically speaking, as different right- wing groups were credited for their contribution to the election of the Republican candidate. Here we can mention religious groups (Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority), New Right groups (adopting Paul Weyrich’s direct mail technique) and Neoconservatives (who supported him through favorable articles and editorials, especially in Commentary magazine). They lobbied for him and were rewarded for it. For example, the Neoconservative Jeane Kirkpatrick was nominated first as a presidential foreign policy advisor, then as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations for over four years, which is an ironical appointment for a group so critical of multilateralism. Political analyst Mark Gerson confirms that Jeane Kirkpatrick won the president’s favors for the position thanks to one of her articles published in Commentary and entitled “Dictatorships and Double Standards”. In that article, Kirkpatrick laid the basis for what would soon be a main feature of neoconservative foreign policy; namely, the necessity for the United States to engage in trade relationships even with countries potentially hostile to the United States. Her argument was that it made no sense to refuse engagements with dictators as these dictators would become communist- oriented in case of an American boycott (Gerson 177). In other words, Kirkpatrick argued that the United States should not exchange right- wing regimes with even less democratic left wing regimes. It is interesting, at this point, to note that young neoconservatives would challenge this very “Kirkpatrick doctrine” in the 1990s, as they grew more concerned by the Wilsonian crusade to spread democracy notably in the Middle- East. Dictated by a Cold- War context, the Kirkpatrick doctrine was heard in the upper tiers of the Reagan administration. Reagan applied Kirkpatrick’s doctrine through his support (or at least toleration) of leaders such as Augusto Pinochet in Chile and Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines.

The appointment of Kirkpatrick was not an isolated case. The following personalities are Neoconservatives who held important positions within the first and second Reagan administrations:

a) Seth Cropsey, former Caspar Weinberger’s speechwriter.

b) Richard Perle, Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Policy.

c) John T. Agresto, National Endowment for the Humanities Deputy Chairman.

d) Elliott Abrams, Assistant Secretary of State for International Organizations.

e) Alan Keyes, Assistant Secretary of State for International Organization Affairs.

f) Paul Wolfowitz, Head of Policy Planning at the State Department.

g) Max Kampelman, Chairman of the U.S. Delegation to the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe.

h) Richard V. Allen, Assistant to the President for National Security. (Halper and Clarke 173).

Seven out of these nine nominations (Kirkpatrick included) are Foreign Policy positions. Under Reagan, the Neocons focused on the best ways to be devised for an efficient opposition to Communism. Pushing for a stronger military build- up and support of paramilitary groups (in Central America especially) became priorities both for the administration and the neoconservative component [1].

To sum up, Neocons had many reasons to be satisfied with their experience in the Reagan administration. A lot of decisions and actions taken by the administration served neoconservative goals, though not deliberately designed for this purpose. Among these, we can cite the military buildup, interventions in Central America and Grenada, and the bombing of Libya.

The Neoconservatives in the Bush Jr. administration: High Momentum

The term Neoconservatism gained currency and recognition in the immediate aftermath of the 9- 11 events. As the upper tiers of the decision- making system were looking for viable answers first to understand then to counter the new type of threat, the Neocons devised a clear blueprint for the purpose. Already well- established within the Bush Jr. administration, they were able to catch the historical moment and move forward their ideas and world vision, in a way that permanently shaped U.S. Foreign Policy ever since. In those defining moments, an intellectual and political task force composed of pure Neocons and Neocon sympathizers surrounded the President:

“Paul Wolfowitz was appointed Deputy Secretary of Defense, Douglas Feith became Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, Lewis’s ‘Scooter’ Libby was made Vice President’s Chief of staff; Elliott Abrams was the National Security Council staffer for Near East, Southwest Asian, and North African Affairs whereas Richard Perle was a member of the Defense Policy Board. Also, Peter Rodman and Dov Zakheim were named Assistant Secretaries at Defense, and John Hannah was named Vice- President Dick Cheney’s Deputy Director of the Staff” (Piper 12). In addition, two neoconservative ‘masterminds’ secured themselves a privileged position within the administration: Karl Rove, the president’s most influential advisor (already his aide during the gubernatorial race in Texas in the mid- nineties). Part of the team was also Commentary and National Review columnist David Frum, who specialized in speechwriting for the president. For instance, he was credited for coining the expression ‘axis of evil’ (to refer to Iraq, Iran and North Korea) which the president introduced in his famous 2002 West Point speech and his State of the Union Address of that same year too.

The Neocons offered clear answers to the complex issues of ‘War on Terror’, ‘Fundamentalist Islam’ and ‘US. Interventionism.’ From their lens, the situation evidenced the following points:

i. The United States were under attack and with them the whole Western democratic world, from a new type of enemy.

ii. The enemy relied on unconventional terrorist attacks, not on sophisticated military armament, hence the difficulty to oppose it.

iii. The new enemies came from states without any democratic tradition and hostile to Western values (though this view neglects that, for instance, the 9/11 hijackers were educated in the Western world and were hence familiar with Western democracy, which they rejected even more).

iv. The most efficient manner to fight terrorism is preemption and targeting harboring states. The U. S. has been taken by surprise on 9/11 and would have to anticipate action in its aftermath.

v. Of equal importance is to spread democracy in those countries representing a potential threat. Hence, the creation of democratic states in certain regions of the world is seen as the best protection that the United States can have (a statement of the famous principle that ‘democracies don’t go to war with each other’). Reshuffling the political organization of nondemocratic areas is, therefore, to be considered seriously.

So, neocons concluded that history proved them right when they expressed their worries concerning the fragility of democracies and the need to protect them through means of preemptive action.

The subsequent interventions in Afghanistan then in Iraq ought to be understood as the Bush administration’s pen and paper application of the Neoconservative agenda. In fact, both incursions illustrated the following Neocon classical tenets:

i. Pre-emption: It is preferable to address military strikes to enemies suspected of developing weapons of mass destruction before they are in full capacity of possessing them and using them against the United States and other Western democracies;

ii. The Noble Lie: A theory developed by the mystical and referential Leo Strauss, an early and mid- 20th century American philosopher from German origins, considered by many as the true founder of the Neoconservative idea. Strauss believes that it is morally acceptable for the political elite to hide part of the truth to the public and even to manipulate facts, because the spheres of perception and understanding of the elite and the public are different. Clearly, this principle was exemplified by the ‘Weapons of Mass Destruction” issue to justify intervention in Iraq in 2003.

iii. The Idealist Quest for Democracy: Almost chivalric in principle, and very idealist politically speaking, this endeavor stems in a Neocon utter belief in the power of Democracy to solve problems of governance, to guarantee stability and to reduce terrorism. Neocon discourse is infused with odes to Democracy as the ultimate horizon for humanity to aspire at. Even if takes military presence to impose it. The influence of Francis Fukuyama’s “End of History” is evident here.

Actually, Francis Fukuyama noticed the total superposition between the Neocons and the Bush administration: “Neoconservatism has now become irreversibly identified with the policies of the administration of George W. Bush” (xi). Fukuyama actually suggests that the president had ended up fully converting to the precepts of Neoconservatism by the end of his first mandate:

On the question of whether George W. Bush is, or ever was, a neoconservative, it seems to me that by the beginning of his second term he had become one. As a candidate he spoke relatively little about a Wilsonian agenda in foreign policy and famously argued in 2000, “I don’t think our troops ought to be used for what’s called nation- building. I think our troops ought to be used to fight and win war.” (46)

Fukuyama does not hesitate to inscribe Bush within the neoconservative family, mentioning his skepticism over the issues of nation building and social engineering as clear testimony of his neoconservative conversion after four years in the White House.

In sum, the Neoconservatives seized the 9- 11 opportunity to rise to prominence at the levels of ideas, platform, blueprint and political agenda. They imposed their world vision as indeed the major International School in Foreign Policy in the new millennium and enjoyed the privilege of power and decision- making at the highest levels. The results and consequences of the Neocon takeover, however, left much to be desired as both Iraq and Afghanistan rapidly transformed into quagmire, and as the limits of Neocon idealism became all too clear to see. The rise of the movement was followed by an inevitable decline amidst critical voices accusing Neoconservatism of fomenting hate, serving terrorism rather than eliminating it, and dragging America into infinite wars in the very complex and complicated area of the Middle- East. Even Francis Fukuyama, the historical “prophet” of the movement, stepped back significantly on his own End of History thesis and admitted America’s (and the Neocon’s) failure at social engineering in Iraq, making the whole Neocon ideology open to revision and reinterpretation in light of new realities. This call for reforming the Neocon project and ideal is the central thesis of his “America at the Crossroads”, published in 2006.

Back to Business: The Neoconservatives under Trump

Neocon swing form Clinton to Trump

By November 2008 and the election of Barack H. Obama to the White House, Neoconservatism looked worn out, denied by hard reality, and – in the eyes of many analysts- illegitimate. As the war in Iraq continued with little progress achieved on the ground and no clear- cut military victory to boast about, it seemed that the Neocon momentum had already dissipated and lost touch with the American people in general. It seemed clear that the Neocons, albeit present numerically in the two Bush administrations, failed in creating and solidifying a strong constituency to mobilize on electoral appointments. Consequently, they failed in appearing as a consolidated political force to be reckoned with. Stephen Wertheim notes that “it was due to their basic intellectual commitments, and not just their particular policy failures, that Neoconservatives spent the Obama years on the defensive, carping about Obama’s supposed weakness but unable to put forward a fresh program of their own” [2].

After years of silent observation and laying low, the Neocons chose to side with Democratic candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton during the 2016 Presidential campaign. If this choice can sound surprising, it is actually a reflection of the movement’s fidelity to its founding Foreign Policy tenets: International affairs matter, the security of Israel matters, and an upfront led hard Foreign Policy matters too. In those criteria, Clinton perfectly responded to the identikit required by the Neocons, and therefore she gained their sympathies. This Neocon positioning also shows that to them, party lines are not un- crossable boundaries. With a dose of pragmatism, Neocons followed the candidate whose Foreign Policy they appreciated since her time as Secretary of State (2009- 2013), regardless of her being a Democrat.

Obviously, the unlikely encounter Clinton- Neocons looked very much like a tactical alliance cemented by anti- Trumpism. What opposed Clinton to Trump was all too clear during the campaign, but what pitted the Neocons against the Republican candidate was more ideological than political: the Trump world vision, bent on relative isolationism, authoritarianism and ‘America First’ rhetoric was anathema to the Neocon vision of International Relations based on internationalist unilateralism, the missionary ordeal, and democratization. Wertheim reveals a major aspect of this Neocon- Clinton cooperation: “Among other efforts, the Center for American Progress (CAP), the leading Clintonian policy shop, is now issuing joint reports with the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), the leading Neocon incubator, which this year sent John Bolton to be National Security Advisor. CAP donated $200,000 to AEI in 2017. The think tanks’ latest joint missive defends the ‘rules- based international order against Russian- backed transatlantic populism” [3]. Therefore, this encounter between the two unlikely allies was set on the common Neocon/ Liberal view of the international scene as a stage where the American interest precisely lied in total opposition to populism and its adventurous agenda.

The Clinton- Neocon alliance, proved to be no more than a transient encounter, dictated by the constraints of the electoral campaign, and realpolitik. Clinton obviously had much to win from the alliance: the Neocons never had a solid constituency to represent, but at the level of the battle of ideas, the Democratic candidate certainly benefitted from attracting this historical component of the Republican Party to her sphere of influence, albeit just temporarily.

As Donald J. Trump gained access to the White House, however, the alliance had no longer any rationale.

The Neocons averted Trump for many reasons. First, he lacked the intellectual depth Neocons assumed they enjoyed; he was yet another ‘populist’ in their eyes, an inappropriate answer to relevant questions regarding globalism, the place of America in the world, and national interest. If compared to Bush Jr, Trump had no previous political experience (Bush was Texas Governor before becoming president), and his style as candidate then later as president, was chaotic and confused.

Yet, it is Trump who revived Neoconservatism and the Neoconservative idea, even though involuntarily.

Donald Trump and the Neoconservative revival

It is not the object of this paper to argue that Donald J. Trump was, is or might become a Neoconservative devout. He never was and never will be. Rather, we will try to show that he ended up indirectly resurrecting the Neoconservative idea because of the new context of International Affairs that has been set up since his election [4].

As discussed above, the Neoconservative school suffered the Bush years and their legacy. As the entanglement in Iraq grew unpopular and unproductive, the ideology that rationalized it lost ground and had to lurk in the margin of affairs during the Obama years. The latter’s stamp on US. Foreign Policy consisted in “leading from behind”, whether regarding U.S- China relations, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan or management of the Arab Spring. In itself, this Obama Foreign Policy approach signified a final rejection of the Neoconservative leitmotiv of ‘democratization at any cost’ and ‘American moral superiority.’ It was a clear ideological defeat necessitating revisions and amendments. It seemed that the Neoconservative movement had run out of steam for the following reasons:

I. Neoconservatism was born in opposition to Communism. Neocons identified themselves as “ex- leftists mugged by reality” who knew all too well about the excesses of Communism and matured considering it antithetical with what the United States stood for politically, historically and morally. As the Communist threat dissipated, the first generation of Neoconservatives found itself without a clear, identifiable enemy to confront in their favorite domain: that of ideas. The Irving Kristol generation retired at this precise junction.

II. The events of 9- 11, as discussed above, certainly gave Neoconservatives momentum and domination. Their answer to Fundamentalist Islam and Terrorism was a textbook application of the precepts they defended in the 1990s, exemplified by the “Letter to President Clinton (1997)” in which they urge him to topple the Saddam Hussein regime in order to prevent coming terrorist attacks against American targets. The movement was unified, mature and coherent. Through its political, journalistic and philosophical components, it successfully imposed its world vision on the Bush Jr. administration. However, it failed in nation- building and social engineering, turning Iraq and Afghanistan into chaotic and ungovernable countries. In terms of terrorist threat reduction, the Neocon strategy was met with very limited results. The Francis Fukuyama generation retired at this junction [5].

III. What the Neocons needed after 2016 was rejuvenation of the project. The challenge was to continue being faithful to the original Neocon idea and project, while also adapting to the new realities of a changing world. Involuntarily and unideologically, Trump helped in this process:

IV. Like Neoconservatives, Trump despised global institutions such as the United Nations and NATO. The Neocon rejection of multilateralism stems from their belief in power politics; while Trump’s rejection is justified primarily by the excessive costs, he believes the U.S. is paying to finance these institutions, for limited political results;

V. Like Neoconservatives, Trump has often expressed clear messages of Islamophobia. The Neocon rhetoric is infused with attacks on radical Islam as a political contender, while the presidential discourse on this matter is much less politically correct and tends to be frontal. Still, there seems to be strong agreements on how the Islamist threat should be assessed and treated;

VI. Like Neoconservatives, Trump pointed fingers at Globalism as the central threat, suggesting “Americanism’ in its stead. The type of Globalism rejected by Neocons is the one which marginalizes the United States and put it in an equal position to any other country of the world. The type of Globalism Trump wants is the one which asserts the role of the United States as the major actor of international relations, not just yet another player in the team. This is not isolationism; it is rather a reshaping of the American role on the global stage. Therefore, both Trump and the Neocons agree on the necessity to move the United States from a position of ‘victim of Globalism’ to a spot of ‘undisputed legitimate leader of the global order [6].

Stephen Wertheim summarizes the surprising alliance:

In the name of opposing globalism, Trump has upheld one pillar after another of the Neocon policy agenda. He is building up America’s already supreme military, to the tune of $750 billion slated for 2019. He is confronting a panoply of adversaries from Venezuela to Iran to China. He has escalated military engagements in parts of Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, without leaving a single of the nation’s dozens of formal security obligations around the world. He has released the United States from multilateral arrangements like the Paris Climate Agreement, UNESCO, and the UN Human Rights Council, and is exiting the Intermediate- Range Nuclear Forces Treaty with Russia. And he has steadfastly supported the right- wing government of Israel, moving the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem and slashing aid to the UN agency for Palestinian Refugees. If Dick Cheney were president, the record would be similar. (Wertheim, 6)

Trump’s policies in the above-mentioned examples do clearly espouse the Neocon world vision. By putting them in practice, the president has refurbished a new version of Neoconservatism and offered it a second life. In any case, many Neocons started dedemonizing him. It is important here to remind that the Trump constituency is made right- wing Republicans and alt- right groups sympathizers, and that the Neoconservatives are distinct form them. The latter, as discussed above, center their interest on Foreign Policy much more than domestic affairs. So from this very lens, Trump has become an acceptable figure to many Neocons. The best example of the normalization is the appointment of veteran John Bolton as National Security Advisor on April 9, 2018. Bolton is a historical Neocon, famous for his hawkishness and extremism. He was present in every Republican administration since Reagan. His discourse has always been anti- multilateral, and in a famous tract published in 2010, he shifts attention to this opposition between “Americanists and Globalists”, bluntly accusing the Obama administration of not doing much to preserve the country’s sovereignty. In a word, Bolton’s inclusion in the Trump administration holds a very particular significance both in symbolic and in political terms. Through his presence and contribution, it is the Neoconservative idea that has survived, adapted and melted into the new context [7].

It can be argued that the future of the Neoconservative movement will depend on certain variables:

i. Capacity of adjustment to new political realities, namely that of populism: The populist wave has de facto imposed a particular candidate on top of the country’s political hierarchy. It is now a factor to be reckoned with in analyzing voter behavior and voter preferences. In other words, Neocons ought to review their elitist postures, out of tune with large constituencies among the American public.

ii. Capacity of embracing discourse change (1): Reviewing the pertinence of some of the eternal credos of Wilsonian Idealism, namely the universality of the democratic idea.

iii. Capacity of embracing discourse change (2): Trump’s “normal nationalism” is no longer a taboo concept to Neocons. Rather, it is by assuming the importance of the nationalist idea that a transition to global leadership is possible.

iv. Capacity of embracing discourse change (3): Replacing the idealist notion of ‘American Exceptionalism’ by the more realist ‘American Nationalism securing its interests in partnership with global partners.’

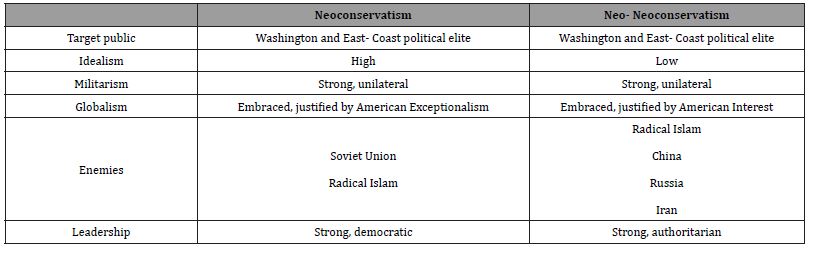

Therefore, a Neo- Neoconservatism would emerge, with the following contradistinctive features.

Table 1:

Foot Notes

1 He left this position on September 10, 2019. President Trump announced that he removed him from office, while Bolton claimed he had resigned.

2 “How Obama Is Endangering Our National Sovereignty”, Encounter Books, 2010.

Conclusion

This paper has tried to delineate the contours of the Neoconservative movement over the last forty years [8]. We have introduced the movement in its ideological particularities and political achievements and limitations, especially during the Reagan and Bush Jr. administrations. Then, we have put the movement to the test of the changes brought by the election of Donald J. Trump in 2016, and we have concluded that it has been able to adjust and survive, so as to continue being a credible and valid Foreign School policy. We suggest the concept of Neo-Neoconservatism to refer to this new brand of Neoconservatism, free from strict ideological commitments and ready to respond to the new challenges emerging on the international arena.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Lechtman, Heather N (1980) The Central Andes: Metallurgy without Iron. In The Coming of the Age of Iron, edited by Theodore A Wertime and James D Muhly, pp. 267-334. Yale University Press, New Haven, USA.

- Hosler Dorothy (1994) The Sounds and Colors of Power, MIT Press, Cambridge, USA.

- Nelson, Ben A , Elisa Villalpando Canchola, Jose Luis Punzo Diaz, Paul E, et al. (2015) Prehispanic Northwest and Adjacent West Mexico, 1200 B.C.-A.D. 1400: An Inter-Regional Perspective Kiva 81(1-2): 31-61.

- Edwards, Clinton R (1969) Possibilities of Pre-Columbian Maritime Contacts among New World Civilizations. In Precolumbian Contact within Nuclear America, edited by J Charles Kelley and Carroll L Riley, pp. 3-10. Mesoamerican Studies vol. 4. Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, USA.

- Meighan, Clement W, (1969)Cultural Similarities between Western Mexico and Andean Regions. In Precolumbian Contact within Nuclear America, edited by J Charles Kelley and Carroll L Riley, pp. 11-25. Mesoamerican Studies vol. 4., Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, USA.

- Mountjoy, Joseph B ( 1969) On the Origin of West Mexican Metallurgy. In Precolumbian Contact within Nuclear America, edited by J. Charles Kelley and Carroll L. Riley, pp. 26–42. Mesoamerican Studies vol. 4., Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, USA.

- Simmons, Scott E, Aaron Shugar (2013)Archaeometallurgy in Ancient Mesoamerica. In Archaeometallurgy in Mesoamerica: Current Approaches and New Perspectives, edited by Scott E. Simmons and Aaron N. Shugar, pp. 1-28. The University Press of Colorado, Boulder, USA.

- Hosler Dorothy, (2009) West Mexican Metallurgy: Revisited and Revised. Journal of World Prehistory 22: 185-212.

- García, Johan, (2007) Archaeometallurgy of Western Mexico: The Sayula Basin, Jalisco as a meeting point of pre-Columbian metallurgical traditions. Bachelor Thesis in Archaeology. School of Literature, Languages and Anthropology. Mexico, Autonomous University of Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Mexico.

- García, Johan, (2008) New knowledge about ancient metallurgy from Western Mexico: cultural affiliation and chronology in the Sayula Basin, Jalisco. Manuscript on file. Center for Materials Research on Archeology and Ethnology, MIT, Cambridge, USA.

- Hosler Dorothy, Rubén Cabrera (2010) A Mazapa Phase Copper Figurine from Atetelco Teotihuacan: Data and Speculations. Ancient Mesoamerica 21 (02): 249-260

- Beekman, Christopher S (2010) Recent Research in Western Mexican Archaeology, Journal of Archaeological Research 18, pp. 41-109.

- Beekman, Christopher S (2009) Formative political systems in the Tequila Valleys, Jalisco and their relationship with subsistence. In: The Complex Societies of Western Mexico in the Mesoamerican World: Tribute to Dr. Phil C. Weigand, edited by Eduardo Williams, Lorenza López Mestas, and Rodrigo Esparza, pp. 75-92. The College of Michoacán, A.C., Zamora, Mexico.

- Weigand, Phil C, Jorge Herrejón y Sean M Smith (2002) Archaeological Project "Los Guachimontones", 2001-2002, Technical Report of the Excavation Units Workshops 1 and Workshops 2, 2002.

- Smith, Michael E (2007) Form and Meaning in the Earliest Cities: A New Approach to Ancient Urban Planning. Journal of Planning History 6 (1): 3-47.

-

Hafedh Gharbi*. The Neoconservative School in U.S. Foreign Policy: Still A Valid Option in Defining America’s Role in the World?. Open Access J Arch & Anthropol. 4(4): 2023. OAJAA.MS.ID.000592.

-

Neoconservatism, Persuasion, Pro- Communist circles, Military buildup, High Momentum

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.