Review Article

Review Article

Perspective and Geometry in the Roman Painted Gardens

Manuela Piscitelli*

Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Department of Architecture and Industrial Design, Italy

Manuela Piscitelli, Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Department of Architecture and Industrial Design, Via San Lorenzo ad Septimum, Aversa (CE), Italy.

Received Date: November 18, 2019; Published Date: November 25, 2019

Abstract

Garden painting is a very precise genre that is distinct from landscape painting. Present in Roman villas but also in tombs of the same period, it responds to some specific compositional rules. The structure of the representation, realized for the most part with the intent to break through the wall to obtain an illusory effect of expansion of space, responds to precise geometric characteristics. The article relates the structure, also geometric, of the Roman gardens with their pictorial representation, which derives from it its justification. In both cases, in fact, the composition is guided by the point of view under which the garden (real or imaginary) must be observed, and in both cases, there is a will to bend nature within rigidly geometric and symmetrical schemas. The sense of perspective recreated in the painted gardens offers at first glance a feeling of naturalness into the garden, which on closer observation reveals the artificiality of a unified and controlled point of view, of rigid symmetries and geometric relationships between the parts.

Keywords: Roman garden; Illusory perspective; Geometry; Symmetry; Painted garden; Naturalistic iconography

Introduction

The relationship between nature and architecture is as old as man’s need to modify the surrounding environment to adapt it to his needs. The garden is the element that most exemplifies this relationship between nature and architecture, configuring itself as the place where man asks nature to sacrifice its form and redefine itself in an imposed model, which, in turn, is inspired by the idea that man has of an ideal nature. Valéry [1].

One could say that the garden was born from the desire to restore the rhythm of nature as it appeared at the beginning, or at least as man imagines it appeared in an original paradise present in almost all religious traditions Portoghesi [2]. In this sense, the garden also stands as the symbol of a condition of lost happiness, memory and representation of an original condition that can be evoked through it. It is no coincidence that the first testimonies of the garden are linked to trees or sacred groves, strongly symbolic elements, to suggest that the nostalgia for a conflict-free relationship with nature is as old as human civilization. From a material point of view, the garden was born as a portion of the Earth separated from the surrounding environment and enclosed by a fence, an idea also connected to the birth of agriculture and the consequent need to protect the crop.

The use of the garden in the modern sense, as a characteristic element of urban planning, began in the Hellenistic Roman age, parallel to the increase in the wealth and consequently in the size of private homes, which had to express the condition of prosperity achieved by the owners. One of the richest documents of this condition is undoubtedly offered by the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, which constitute a fundamental typological and chronological point of reference about the relationship between architecture and landscape in the ancient world. With the introduction of the garden inside the house, there was a substantial cultural change in the conception of greenery, which from a symbolic element, functional to the exploitation of a religious site or to shading theatres, gyms and meeting places for citizens, was transformed into an autonomous element, an integral and essential part of the private architecture. From the Hellenistic world, the idea of the garden of pleasure moved to the Mediterranean West, acting as a tool to differentiate the private home of those who were rich enough to afford it. The Roman garden, however, should not be considered a copy of already known models, but adopted aesthetic, functional and botanical original solutions, adopting cultural contributions from more advanced civilizations in the treatment of green, adapting them to their territory, mentality and lifestyle.

The most significant evolution of the Roman garden took place between the second century B.C. and the second century A.D. and began in Campania, probably because in the peripheral and holiday areas were more easily allowed originality of composition, and then gradually approached Rome. In this period, the transition from the forms of the fruitful garden for the sustenance of the inhabitants to those of the large gardens rich in trees and decorative arrangements took place.

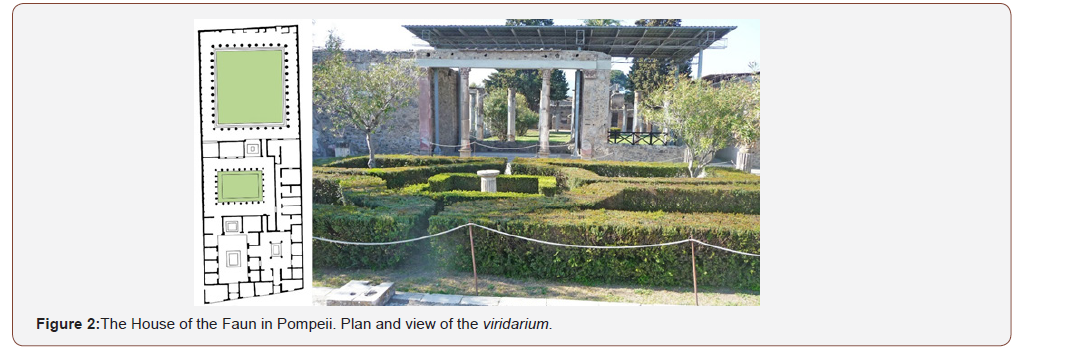

The most archaic Roman house did not have a garden but a hortus located beyond the atrium, in which, according to the model of an agricultural society, the land was cultivated to produce fruit, vegetables, oil and wine, as in the house of the Surgeon, whose structure on the ground floor dates back to the fourth century B.C. During the 2nd century B.C. this cultivated area was enclosed in porticoes on which other rooms were opened, increasing the space of the house. This is the house with atrium and peristyle, described by Vitruvius and represented in a canonical manner by the Insula Ariana Polliana, which experienced great development in the last century of the republic both in the suburban villas and in the grandiose city houses. The villas grew more and more, coming to be arranged around more atria and more peristyles, and including more than one garden, as in the house of the Faun. In the writings of Pliny, the Younger, Cato and Columella there are numerous references to the attention paid to gardening, no longer considered merely a productive occupation, but an activity carried out for pleasure and enjoyment. Pliny was the first to distinguish between gardens intended as vegetable gardens and ornamental gardens, giving news of the fact that the art of designing gardens was quite recent for him, and therefore easily dated to the last years of the first century B.C.

Marco Terenzio Varrone (116-27 B.C.) describes, in his treatise De Re Rustica[3] the fundamental characteristics for a villa: the peristyle - the colonnade - the peripteros - the pergola - and the ornithon, the aviary: all the elements that make up, in summary, the garden environment. Cicero gives detailed information about the Hellenistic fashion that, around 60 B.C, involved Rome in the appreciation and implementation of gardens that became “delightful” changing the concept of the Roman world for which, until then, there was no distinction between the terms of garden and horticultural garden. Vitruvius writes that “in the house of the lords there will be a spacious atrium and a vast peristyle, a park and a place to walk appropriate to the prestige and nobility of the family”.

Despite the fact that in many Pompeian houses the open area of the peristyle remained for a long time a place of cultivation of fruit plants, as in the house of Iulius Polybius, at the end of the Republican age the art of gardening was born, according to what reported by Pliny, even if already in previous times flowers were cultivated for religious or funerary purposes.

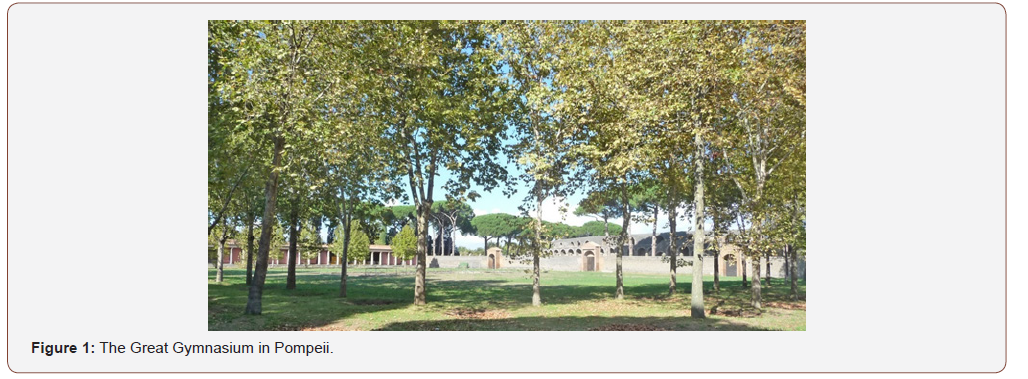

Depending on the type of plant that were cultivated, the garden was called hortus to indicate the space in which vegetables and useful plants were grown; viridarium if instead ornamental plants grew there, planted for aesthetic pleasure Maniglio [4]. The dimensions of the gardens of Pompeii, enclosed between high walls and in rare cases hanging, were extremely diversified, and ranged from 10 to 4000 square meters. They are therefore presented as a vast repertoire of ways in which in Roman times the theme of the garden was declined. The viridari, sometimes tiny, decorated mainly the houses of the central areas of the ancient city, while some houses, the richest, had more than one garden: The House of the Guitarist, for example, counted three. In the peripheral areas, especially near the Amphitheatre, in addition to some public green spaces such as the Great Gymnasium, there were more frequent gardens, vineyards, orchards and crops related to agricultural and craft activities, such as the production of perfume essences or the cultivation of nursery plants. In the gardens there were often spaces for masonry triclinia, altars, sometimes sundials, as well as small domestic farms kept in special terracotta shelters, such as gliraria, snails or dovecotes, further evidence of the close link between nature and architecture. In fact, the peasant cultural roots survived in the relationship between artificial and natural even in the most sumptuous Roman villas, such as the one of Pliny the Younger. Luxury was never an aim, but the natural space retained a precious link with the agricultural dimension, at the same time acting as a place of leisure and reflection and as the fulcrum of a territorial agricultural system that linked architecture to the landscape (Figure 1).

The Garden as a Material of Architectural Representation

If the painted garden refers to the real garden, of which it is a translation into iconographic forms, it is necessary to start from the study of the function and form of the garden in the Roman house. The passage from the forms of the garden for sustenance to those of the garden of pleasure is perfectly documented by the evolution of the houses of Pompeii. In the older houses, beyond the atrium and the tablinium, we notice the presence of a small viridarium, which over time expanded and enriched without ever becoming a luxuriant park on the model of the oriental “paradise”, since an irrational and multiform conception, with an apparently confused arrangement of the essences and without a correspondence to a specific architectural form was extraneous to the Roman conception of space

From an aesthetic point of view, Romans preferred the forms of the built garden rather than those of the natural garden, so they adopted solutions aimed at creating organically aggregated buildings, for example limiting the garden with a portico on one or more sides. In the structure of the Pompeian domus the garden is an integral part of the house, but is architecturally divided from it, juxtaposed and often with an independent entrance at the back of the insula. In Pompeii the typology is very varied: for space requirements the sides of the peristyle could not all be colonnades, or the garden could be enclosed within the walls. The gardens were also found in taverns and in some shops, as well as in temples, gyms, theatres and thermal complexes, testifying the habit of living outdoors. The garden is subject to architecture: the picturesque motifs are always related to an architectural element and often it is the portico that guides the composition. Building and open space appear intimately linked, and inevitably the garden becomes a part of the architecture, a completed composition. Grimal [5].

In the Roman garden flowers did not predominate but were mainly used evergreen plants from whose composition could occasionally emerge flowers as spots of colour. From the peasant culture survived the richness of botanical knowledge and consequently of the species used, which were skilfully shaped to create new landscapes and impose the desired shape on nature. The flowerbeds were fenced in with wooden or reed grillages, as depicted in the frescoes. The method to adapt nature to a desired composition, almost architectural, was that of ars topiari, or the art of shaping places. Topia is a Greek word that was used to describe wall paintings depicting elements of landscape, rocks, streams, groves, mythological figures, animals, but not real landscapes. Hence the topiarius, intended as the creator who through the arrangement and pruning of plants, had to create compositions that were inspired by these topia. Vannucchi [6].

The garden thus from scenery becomes the material of representation. Nature is used as an element for the construction of an architectural identity linked to its own characteristics and components, depriving it of its natural characteristics. They are looking for an image to impose on nature to underline the function that man wants to attribute to it: idleness, reflection, sports, etc. This search for attribution of an image also took place through pruning with geometric, architectural or animal motifs, sacrificing nature to an aesthetic formal value in a garden that is the very negation of nature. Only later did ars topiaria pass to indicate only the figurative pruning of the plants, losing the original meaning of artistic construction of the places. In Pompeii the ars topiaria, in the sense of the creation of great scenic effects, was little applied, as it adapted to very large and luxury spaces, intended for large parks of the richest. The small gardens of Pompeii, on the other hand, even when used as a delight, tended to maintain a reference to their original function of sustenance; for example, they were the pharmacy of the house or provided fresh fruit. In fact, in the flowerbeds were often inserted for ornamental purposes plants that could also be useful as medicines. Ciarallo [7].

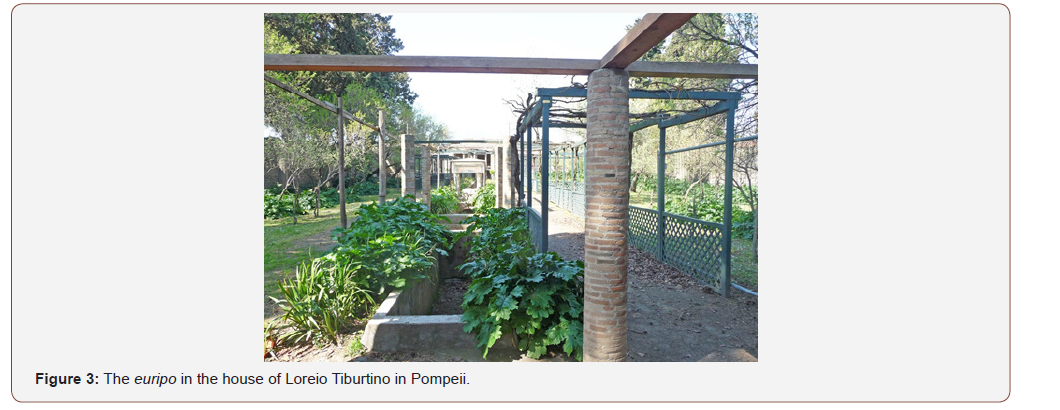

Architecture, botany and hydraulics can be considered the structural components of the garden, where vegetation becomes architecture in the sense that it defines complex scenarios and perspectives, in which the tree, the flower, cease to be only themselves to be at the service of a fiction. First of all, architectural fiction. Grimal [8]. The schemes and rhythms of architecture were declined in the garden in the relationship between full and empty, closed and open spaces, articulated between pergolas, colonnades, statues, hedges and canals, with backgrounds and trompe l’oeil perspectives. The shape of the garden repeated the principles of geometry and symmetry typical of architecture, for example by structuring the space and defining paths through the construction of trellises. Water, flowing from the fountains and flowing through the garden, was also used as an element of the architectural composition. In the house of Loreio Tiburtino, the water channel, known as the euripo, was the main axis of the entire construction of the garden and the spring was located under a pavilion to accentuate its importance.

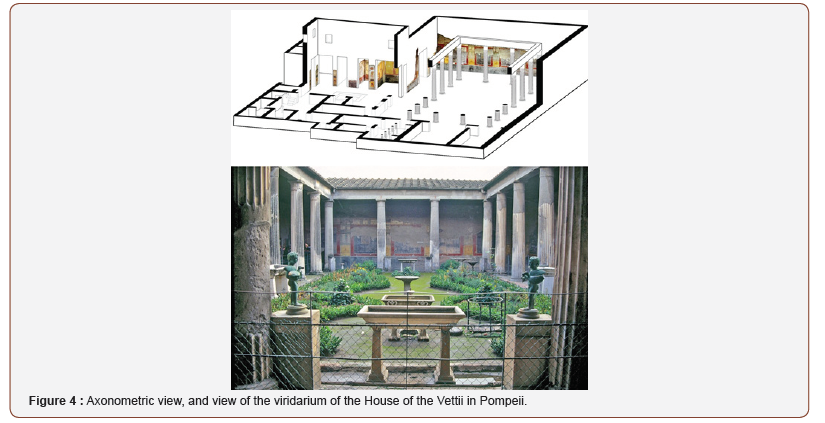

The living practice of using water as an element of decoration of the domus spread during the first century AD. The construction of the urban aqueduct and the consequent increased availability of water contributed greatly to the success of this taste. The construction of the Augustan aqueduct and the consequent abundance of water allowed the cultivation of many ornamental plants and spread the fountains as a decorative element of the garden. The configuration usually involved a division into horizontal and vertical paths, with the fountain in the middle and sculptures along the paths, often created or adapted to allow the water to spring up. In the house of Vetti the ancient plumbing system with its valves is still working and feeds fourteen fountains in the peristyle. Borghi [9].

The excavations have brought to light the constituent elements of the hydraulic systems: pipes, valves, siphons, goblets, separators, etc. The shape and size of these devices were precisely calculated on the basis of fixed modules, as evidenced by the De aquaeductibus urbis Romae, written by Frontino at the end of the first century A.D. Parts of valves, taps and junction boxes account for the complex hydraulic systems that guaranteed the prosperity of the plants. The Citation: Manuela Piscitelli. Perspective and Geometry in the Roman Painted Gardens. Open Access J Arch & Anthropol. 2(1): 2019. OAJAA. MS.ID.000527. DOI: 10.33552/OAJAA.2019.02.000527. Page 4 of 9 importance of water as a fundamental element in the composition of gardens is demonstrated by the fact that excavations have never brought to light a garden without an irrigation system, while on the contrary private aqueducts have been found built for the sole purpose of watering a garden. The bronze and marble sculptures used as fountains and basins for the collection of water are further evidence of the relationship between nature and technique (Figures 2-4).

Illusory Perspectives in Painted Gardens

The freedom of typological planning, the overall articulation of the rooms and the relationship between full and empty spaces is present both in the villas of Pompeii and Herculaneum and in Rome itself also in the pictorial representations, which provide complete images of some sumptuous villas of the time in which the arcades are sometimes not limited to the ground floor, but also appear on the upper floors. The motif of the fenced garden (hortus conclusus) is a refined decorative element, characterized by an accurate and meticulous design, which spread in the Roman world from the first century B.C.

The miniature gardens used as ornamental motifs were organized according to a precise symmetry around a centre occupied by a fountain, a statue or an aedicule, and were geometrically articulated through partitions made of cannulated fences. The view was always represented from above, so that the entire structure could be seen at a glance. The constituent elements were always the same, even if declined in variants always different, as well as constant appear the motifs, the constructive principles of geometry and symmetry. These compositions can be considered miniaturized representations of existing gardens, as we can see in the Vesuvian area. De Vos hypothesized that these paintings reproduced half of the real garden, with a point of view, that of the landlord, located in the centre of the garden, in the central open space. To have the design of the entire garden it would therefore be necessary to symmetrically overturn the half represented, because the view constitutes only half of the structure. This type of painted garden would therefore refer not so much to the real garden as to its design, of which it constitutes a representation from a particular point of view, that of the owner who must choose the project to build his own garden. De Vos [10].

The proper garden painting, on the other hand, wants to obtain the effect of breaking through the wall by simulating the presence of a real garden. Here, too, the structure of the representation is dominated by norms, conventions and rules of perspective. The purpose of the representation is the same, that is, the representation of a real garden, but while in the case of miniature gardens it was translated into an overall view, here it is accurately reproduced in real scale. The two types of representation, which at first glance may appear very different from each other, are comparable in terms of the finiteness of the space and the geometric organization of the garden. Settis [11].

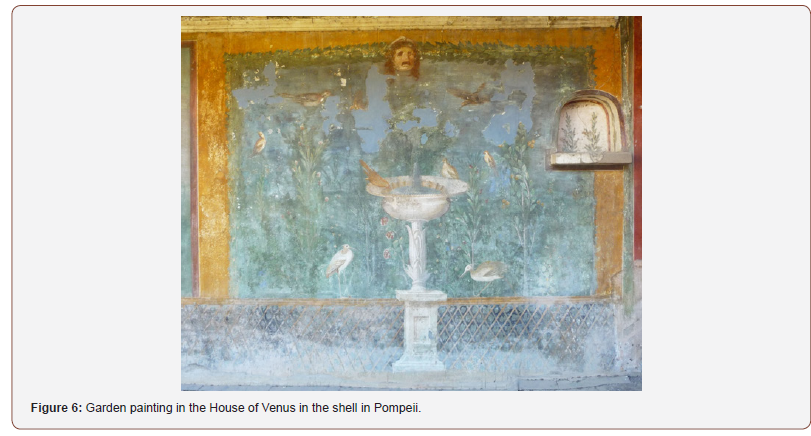

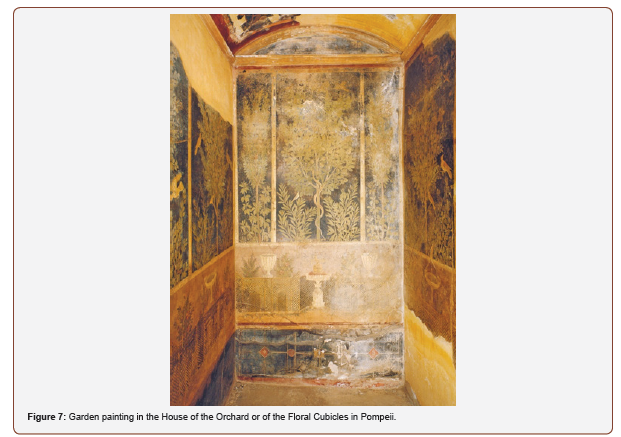

Elements that are sometimes repeated are depicted: obviously the vegetation that forms the background and then architectural parts of decoration such as fences of various types, oscillations, fountains, herms and statues. The numerous examples found in Pompeii and Herculaneum, although presenting the same composing scheme, differ from each other for the different shape that can take the fence and for the inclusion of birds and shrubs of various species, fountains, aediculas and statues. The use of illusionistic techniques made it possible to create gardens that were apparently of great realistic effect, for the precision and detail of the plant and animal elements and the use of wings that materialized the scanning of planes and the depth of field. A more careful analysis shows that elements that could never have coexisted were represented at the same time, such as characteristic flowers of different seasons of the year or birds belonging to distant territories. This wall decoration with plant motifs was like a sort of trompe l’oeil, which carried the garden inside the houses and which, in the outdoor areas, was the scenography for the real garden.

Garden painting must be considered a specific genre, which can be placed in the Third and Fourth Pompeian Style (25 B.C. - 79 A.D.). The genre of garden painting was probably born in the funerary field, to then know great fortune with the representations of gardens connected to the life of mortals, to the point of representing the typical element of the Roman villa, that every citizen, to whatever class belonged, wanted to recreate even only in painting, if he could not afford a real garden. When this was missing, the walls behind the fountains were intended to simulate it with paintings that reproduced trees and shrubs, birds and animals. To create the illusion of depth, these painted gardens were often bounded by barriers or trellis. (Franchi, 1990).

The flora and fauna depicted were full of symbolic meanings that made the painted garden a utopia in the literal sense of the term, that is, a non-place in which man tried to bring out, using the elements of the real world, the world of his dreams. So, in the horti picti they tried to recreate a lost world, belonging to the mythical golden age. The great diffusion of this kind of painting in different types of buildings, from stately homes to simple dwellings, testifies to the fortune it had with commissioners, who wished to increase through painting the real boundaries of green spaces, sometimes small in size, creating a garden adorned with marble and populated by rare and colourful animals. In Pompeii, out of 323 houses with roadways or partially colonnaded gardens of small dimensions, 51 have the walls of the green space frescoed with garden paintings with the intention of illusorily enlarging the real garden. Settis [11].

Pierre Grimal, quoting Vitruvius, hypothesized a two-way link between landscape painting and the real garden: “The invention of the Roman gardeners consisted simply in detaching the painted landscape and transporting it to the outdoor area that bordered the portico”. Grima [8].

In support of this hypothesis, we can also cite a passage by Pliny the Younger, who in describing a cubiculum of his villa in Tusci establishes a close parallel between the paintings that adorned the walls and the natural frame of the environment itself. This is a possible key to the function and meaning of garden painting: it was certainly a source of pleasure, as Pliny the Younger himself recalls, but it was because it expanded the space on an “open” and natural perspective. Plinio il Giovane [13].

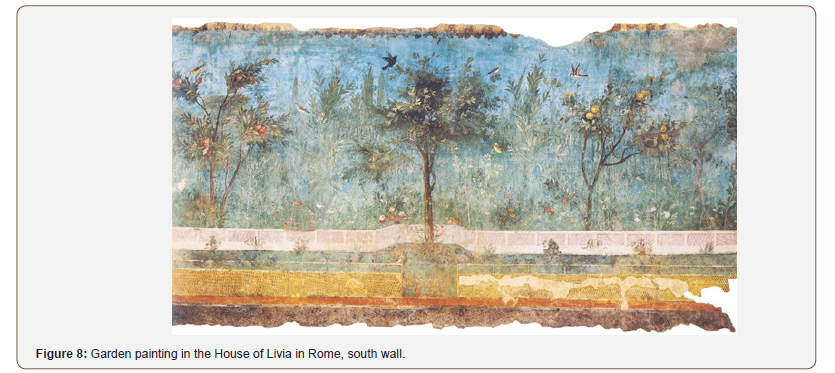

The link between royal gardens and paintings is also indicated by Salvatore Settis, according to whom the genre of garden painting is the result of a fusion between pictorial fiction and reality, whose purpose was to suggest the illusion of a real garden. In support of this hypothesis is reported the example of the underground nymphaeum of the villa of Livia di Prima Porta in Rome, which has preserved an incredible wall painting of a frescoed garden dating from 40-20 B.C. The lack of light and air in the underground environment is in contrast with the subject of the pictorial decoration, an airy garden depicted in detail and with great variety of plant and bird species, life-size and without interruption even at the edges. In the absence of vertical architectural elements such as columns or pillars, the perspective of the garden is skilfully obtained by the representation of horizontal elements: the fence of reeds and branches of willow in the foreground and a marble balustrade in the background. Between these two elements, the real garden comes to life, with colourful trees rich in flowers and fruits and birds of different species. The double fence has the function of illusorily defining the green space, distancing the viewer from the plants placed beyond the balustrade. The sense of spatial depth is further underlined with other devices, such as the reduction of the details of the plants, very accurate for those in the foreground, to the point of allowing a precise botanical analysis of each plant, and gradually more approximate and shaded in the distance; a very rare and innovative sensation of the atmosphere obtained thanks to the fine variations in colour that end in an airy turquoise of the sky, the final boundary of the gaze; the sensation of movement given by the presence of birds in flight and branches with the tops bent by the wind. The composition of the garden, as in a real garden, is organized according to a symmetrical scheme: at the centre of the walls are arranged the main trees, flanked by other trees in balanced compositions according to precise compositions rules. On the contrary, the spatiality of the nymphaeum is illusorily prolonged, denying its walls as if they had been broken through painting, or as if it were a glass pavilion surrounded by a real garden. Settis [11].

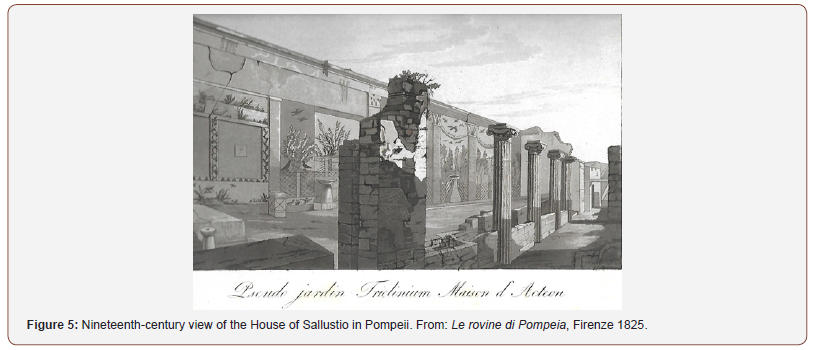

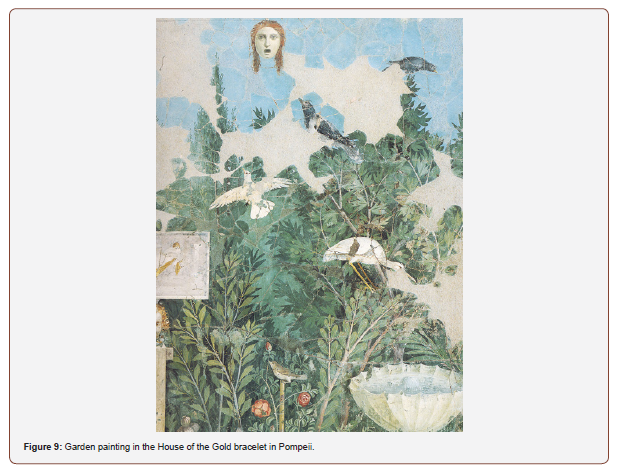

Returning to Pompeii, it is in the frescoes of the House of the Gold bracelet that the naturalistic iconography of the time reached its peak. In the triclinium of the house, a garden fresco has been found in fragments and reassembled, showing a framed cannula, with lush vegetation reproduced with meticulous care, inside which birds of all kinds fly and rest; above it hangs around marble oscillum. Here, as in Livia’s villa, the viewer could see the vegetation that developed on several levels dematerializing the wall surface and creating the illusion of depth and identify with certainty the plant species represented in detail, testifying to a strong spirit of observation. As in the Villa of Livia, therefore, painting dematerializes the wall creating a deceptive spatiality with a weak boundary between the real space and the illusory perspective on the painted garden [14-30] (Figures 5-9).

Conclusion

The discovery of Pompeii was the engine of an aesthetic consecration of the ruins, that is the diffusion towards the public of the idea of an aesthetic value of these landscapes, and as such it became part of the composition of new paintings and new gardens. Over time, ruin, whether authentic or artificial, has been one of the most significant elements in the design of gardens and landscapes, both real and painted. The aesthetic of ruin has not been limited to landscape representations but has become the real material of the composition of greenery. Diderot e D’Alembert [11].

The relationship between painting and the garden then took on new meanings: for the ancient garden, the presence of painting in the gardens was discussed, symbolically enriching the semantics of their space through iconography; now, on the contrary, painting is seen as a model of the garden, which draws inspiration from it until it reaches its peak in 18th century England through the different aesthetics brought together under the notion of picturesque. In this sense, the ruins of Roman villas and their representations have perpetuated over the centuries the ancient dialogue between nature and architecture, art and garden, reality and fiction, enriching it with new meanings and extending its cultural influence far beyond its geographical and temporal boundaries.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Instrest

No Conflict of Instrest.

References

- Valéry P, R Contu (1932) Eupalino o dell’Architettura, trad. Lanciano, Italy.

- Portoghesi P (1999) Natura e architettura. Milano, Italy.

- De Re Rustica. Varrone, Italy.

- Maniglio Calcagno A (1983) Architettura del Paesaggio. Evoluzione storica, Bologna,

- Grimal P (2000) L’arte dei giardini, una breve storia. Roma,

- Vannucchi M (2003) Giardini e Parchi. Storia morfologia ambiente, Firenze: Alinea.

- Ciarallo A (2006) Pompei Verde. Napoli, Italy.

- Grimal P (1990) I giardini di Roma antica. Milano,

- Borghi R (1997) L’acqua come ornamento nella domus pompeiana, in: L. Quilici e S. Quilici Gigli, Architettura e pianificazione urbana nell’Italia antica, Roma: L’erma di Bretschneider.

- De Vos M (1983) Funzione e decorazione dell’auditorium di Mecenate. In: L’archeologia in Roma capitale tra sterro e scavo. Catalogo della mostra, Venezia, Italy, pp. 231-247.

- Settis S (2008) Le pareti ingannevoli. La villa di Livia e la pittura di giardino, Milano, Italy.

- Ciarallo A (2004) Flora pompeiana, Italy.

- Plinio il Vecchio, Storia Naturale.

- Diderot e D'Alembert (1765) Encyclopédieou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, voce “ruine” XIV.

- AA VV (1993) Historic parks and gardens, literary parks. Knowledge, protection and enhancement. Proceedings of the III Conference "Landscapes and gardens of the Mediterranean", Pompeii, Italy.

- AA VV (1992) Domus, viridaria, horti picti. Catalogo della mostra, Napoli, Italy.

- Allison P (1997) Artefact distribution and spatial function in Pompeian houses. In: The Roman family in Italy.

- Bianchi Bandinelli R (1976) L'arte dell'antichità Etruria-Roma, Torino, Italy.

- Camus A (1988) Opere. Romanzi, racconti, saggi, tr. It. Milano,

- Cardini F, Miglio M (2002) Nostalgia del Paradiso. Il giardino medievale,

- Crawford D, Nature and Art. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Italy.

- Columella, De re Agricola, Italy.

- De Caro S (1991) Due generi nella pittura pompeiana: la natura morta e la pittura di giardino, In: M. G. Cerulli Irelli, La pittura di Pompei. Testimonianze dell’arte romana nella zona sepolta dal Vesuvio nel 79 d. C. Milano (Ed.), Jaca Book,

- Di Pasquale G Paolucci F (2007) Il giardino antico da Babilonia a Roma. Scienza, arte e natura, Livorno,

- Jashemski WM (1979) The Gardens of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and the Villas Destroyed by Vesuvius. New Rochelle New York, USA.

- Maiuri A (1931) Pozzi e condutture d’acqua nell’antica Pompei, Italy, pp. 546-576.

- Maniglio Calcagno A (1983) Architettura del Paesaggio. Evoluzione storica, Calderini, Bologna.

- Negri R (1965) Gusto Epoesia delle rovine in Italia frailSette e l’Ottocento. Milano,

- Plinio, Lettere Familiari Il Giovane, Italy.

- De Architettura. Vitruvio, Italy.

-

Manuela Piscitelli. Perspective and Geometry in the Roman Painted Gardens. Open Access J Arch & Anthropol. 2(1): 2019. OAJAA. MS.ID.000527.

-

Natural Language Processing, Geographic Information Systems, Corpus Linguistics Roman garden, Illusory perspective, Geometry, Symmetry, Painted garden, Naturalistic iconography.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.