Research Article

Research Article

Least Cost Path Analysis and Conditional Perception of Prehistoric Travelers

Tsoni Tsonev*

Interdisciplinary Studies and Archaeological Map of Bulgaria, Archaeological Institute and Museum, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Bulgaria

Tsoni Tsonev, Interdisciplinary Studies and Archaeological Map of Bulgaria, Archaeological Institute and Museum, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Bulgaria

Received Date: February 01, 2022; Published Date: February 09, 2022

Abstract

The present study focusses on the unexplored so far relation between the possibilities of Least Cost Path analyses (GIS) to explore higher order prehistoric human behavior. It compares the easiest path to the most difficult one for supply with long blades of the Neolithic populations in Bulgaria. It was found out that the easiest way for travelling encounters several anomalies (mismatch) of the symbolic complexes of foreign, public and private (house) domains of prehistoric communities.

The explanations for this complex phenomenon are sought in the theory of perception. My working hypothesis explores the formal logic that lies behind the capabilities of human perception and improving communication for introduction of the impossible worlds into the possible ones (disjunctive and conditional variants). My supposition is that the relationship between possible and impossible worlds is a scale free which opens new venues for deeper understanding of symbolic behavior of prehistoric communities.

Keywords: Lest Cost Path Analysis; human perception, prehistoric symbolic complexes

Introduction

The present study focuses on a novel way of conceptualizing the Neolithic population exchange and movements. It involves least cost path analysis (GIS) of the most likely travel routes and the distribution of valuable artefacts made of high-quality flints and nephrite. Thus, these dynamic maps are used in order to illustrate the complex scale-free-like symbolic behavior of early farmers.

Next I analyze the relationship established between symbolic and empirical facts generated by these spatial distributions. It is based on establishing the generalized differences between these categories. I focus on differences of symbolic behavior of early farmers (their strong preferences to valuable artefacts and materials). The aim of these procedures is to answer the question what makes possible materials and artefacts for everyday use to gain such high-order social values. How these values constitute the nature of the population movement and travels made by individuals and groups?

The greater variation of symbolic facts and their correspondence to a greater variety of social values appears to be fundamental to deeper understanding of the dynamic of the relationship: empirical – symbolic facts. The central problem is why symbolic facts tend to vary significantly not only relative to their empirical counterparts but also across time and diverse geographic regions? I explore how prehistoric people established relations of harmonizing their knowledge through travels. On this ground a simulation of the basic characteristics of an epistemic basing relation is made. It allowed establishing the relation between ‘pure’ belief and belief conditioned by proofs. Further it is presented the importance of the fractal-like behavior of the established relation between ‘pure’ and ‘conditional’ belief for interpretation of spatial distributions of valuable artefacts and materials for prehistoric communities.

Conceptualization of symbolic complexes of foreign, public and private domains

A plausible assumption about the Neolithic way of life necessarily involves short- and long-distance travels of individuals and groups of people made on seasonal and year round bases [1]. It is easy to conceptualize the Upper Palaeolithic travelers as a group of lonely travelers along their routine or exceptional routes (Anati, 2015). In another case the archaeological record of the European steppes and woodland zone suggests that these were small groups of people from the final Upper Palaeolithic that were living on vast territories and travelled from the Alps to the North European Plain [2].

The conceptualization of Neolithic population movements and regular contacts, however, is difficult to be made. It is easy to present it as a function of social necessity: population pressure combined with compensatory mechanism that aims to amend the partial loss of crop yields or illnesses of domestic herds of animals. If this explanatory hypothesis were true, then in archaeological record it would have been detectable the traces left by the regular human contacts and mass population movements between regions with the most favorable and the most perilous climatic conditions. Contrary to this small-scale population exchange between forager and farming communities has been established by isotopic studies of Neolithic and Mesolithic populations in southwestern Germany [3].

It is plausible to assume that prehistoric travelers passed through completely different human and physical environment. The Neolithic fields, forests, mountains and wetlands were densely populated by people doing their everyday work within the frame of temporary and permanent houses or shelters dispersed over the terrain. The distance between these points of interaction in a given neighborhood will not depend on the Euclidean distance (as in the case of modern travels) but mostly on human communication which may easily be locally redirected according to the grid of densely populated interim meeting points.

A plausible question arises as to whether these people were able to communicate with each other if they belonged to distinct lineages, groups or bands that had different symbolic systems based on different mythological, ritualistic and belief complexes? In answering this question there is a reason to believe that local differences in the symbolic complexes of early farming communities existed. A proper way of analyzing these symbolic differences would be to focus on the nature of long-distance communication and exchange networks. The advance of archaeological science facilitates this approach. It helps to identify and map out the provenance and distribution of valuable artefacts. Yet these studies also show that even the most wide-spread artefacts and materials are not, as expected, normally distributed over the central area of their provenance [4]. While some are more wide-spread than others they all form a kind of patchy or mosaic-like spatial patterns.

On this background it is possible to model the logic behind the interaction between the private, public and foreign symbolic complexes. Locally these complexes may differ significantly but there is common logic behind their interaction. The efficiency of these communicative relationships lies in their ability to introduce the impossible worlds into the realm of the possible ones. In other words they have to explain unknown phenomena by the following reasoning: ‘I believe in A∩B (e.g. when two persons are serious and talk about a particular issue only then their joint statements may be trusted) but I do not believe in A and B as separate phenomena nor in their disjunction A∪B (the two persons A and B are in a mood of making jokes and their words shouldn’t be trusted)’. This is an extreme type of reasoning that may be rarely encountered. People are more inclined to believe in phenomena but only if one of the two co-current arguments (A or B) holds true.

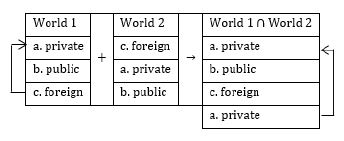

This general logical scheme may be illustrated by the order of top-down interaction of a cyclic sequence (a → b→ c → a) of the symbolic complexes within a given world. If the plausible assumption is made that social priorities will induce top-down hierarchy of symbolic behavior (symbolic of the private, public and foreign domains in early Neolthic contexts in SE Balkans), it is possible to create the following scheme of intersection between World 1and World 2 presented in Table 1. In the above presented scheme neither in the two separate worlds nor in their intersection there is a case where b → a (public domain influences directly the private one). Their relationship is always mediated by the symbolic of the foreign domain.

Table 1: Merging of two symbolic complexes into a single one.

To a certain extent the archaeological record confirms this kind of logic of the symbolic behavior of prehistoric communities. An example of how the symbolic of foreign mediates the interaction between the private and public domains is visible in the largest pit and spot for feasting in the Neolithic settlement of Makriyalos, northern Greece. It was found out that some feasts were more representative than others and may have involved people coming from outside the settlement [5,6]. Similar symbolic behavior is quite commonly encountered yet it may not follow strictly the above presented logical scheme. It outlines a tendency of general interaction.

The harmonizing metaphors behind the dynamic interaction between the different symbolic complexes

Is it possible to model the process of introduction of harmonizing metaphors that equate the meanings of the different symbolic complexes that participate in a given discourse? The first assumption is that there exist local areas where the differences between various symbolic complexes related to different communities should be maximal. Traditional archaeological interpretation schemes have a built-in themselves empirical possibilities of making a prediction where these places most frequently may occur. By analogy with similar modern spatial phenomena the expectations would suggest that these areas involve the most difficult terrains to cross. The archaeological record, however, shows different pattern. For example, the data of distribution of long blades made by highquality flints from outcrops in northern and northeastern Bulgaria are fitted by two least cost routes relative to the relief (Dynamic map of Bulgaria, scale 1: 200 000). The shortest route passes through the most difficult terrain, the longest through the easiest one. On both routes such mismatch (total lack of long blades) occurs. Adjacent to both shortest and longest ways it is the site of Koprivets that exhibits such features. On the longest one the similar sites of Ochoden, Vratsa district [7] and the sites Slatina and Kurilo in the Sofia plain (Figures 1 & 2) occur. These sites are situated in the immediate vicinity of local flint varieties of medium and low quality. In the case of Koprivets the site is situated about 5 km away from high-quality flint outcrops but, unless the nearby site of Orlovets which entirely relies on high-quality flints from this source, the inhabitants of Koprivets never used this outcrop of high-quality flint varieties. The importance of these differences comes from suggestion that there existed general communicative metaphor(s) common for a given region that is related to the provenance of flint varieties and the symbolic and practical use of long blades and the other artefacts made out of them. At certain localities, however, there are strong metaphors of acceptance of particular local flint varieties as opposed to the imported from other sources ones. Even if the outcrops of high- and low-quality flints lie side by side (about 5 kms apart in the case of the Neolithic Koprivets and Orlovets sites) a strong preference remains which divides local communities in their use of flint varieties.

A question arises how it is possible a trivial object for everyday use such as flints to accrue a high-order symbolic value? The answer to this question involves consideration of some aspects of the vast symbolic field of material expressions that mediates between the realms of sacred and profane of the everyday life of prehistoric people. It stems from the assumptions that Neolithic communities did not consist of homogeneous populations. Rather they incorporate different corporate kin-groups which may be further divided into different categories of people such as craftsmen, farmers, collectors of particular wild resources, builders, hunters, healers, persons occupied with specific home and community rituals, etc. Each of these categories of people is sanctioned by specific sacred values because once a person becomes initiated in a given social (“professional”) category he/she holds this position for the entire life. This is an entangled social reality that integrates personal choices, skills and knowledge with complex communication and exchange of valuables. Most likely this process involved the entire kin or lineage group for accumulation of a proper amount of valuables in order a particular person to take up higher order social position in the overall community social structure [8]. Probably some of these initiation rituals involved long-distance travels that are objectified by some material expression such as the provenance of particular flint variety, nephrite, or other valuable materials. It is not the material itself, but the knowledge acquired during that journey that was the real social valuable; a symbolic capital sanctioned by the sacred quality of appropriated materials and tools that attaches importance to belonging to a specific social group.

A question arises as to what is the nature of the human interaction and exchange of knowledge during the frequent encounters along these journeys. It must have been quite different from the modern exchange of rational knowledge and close to the state of encounter of two or more persons each with its own way of being-in-the-world with accumulated common for all parties practical knowledge (in the sense of practical reason of P. Bourdieu [9]) but related by a range of very different experiences and expertise. The crucial question is how diverse expertise knowledge, skills, beliefs reflect in human perceptual experience so that to form coherent messages across different human groups leaving far apart from each other.

Primary quality model assumes experiences of (mindindependent) real-world properties such as geometric forms which characterize almost all visually distinguishable phenomena. This model applies if at least some features of perceptual experience can only be characterized by appeal to a prior, and independent, characterization of the empirical things which may be presented [10]. Contrary to this, traditional archaeological approach studies visible phenomena by analogy with exhaustive empirical research schemes and tries to involve all the possible elements of an assemblage. It is assumed that their built-in secondary qualities (artefact’s attributes) are able to outline an “objective” evaluation of hidden structured patterns of past social actions. To a certain extent these exploratory schemes work well but they are not able to reveal the properties of higher order human behavior. For example, such an approach cannot give a satisfactory answer why humans used the same spectrum of colors for the entire prehistoric period (Palaeolithic and Neolithic ones).

It is for these reasons that it is necessary to make a distinction between the empirical and symbolic facts. Although this distinction may be subjective it is in accordance with the ‘Primary Quality Model’ of human perception [10]. The secondary qualities such as color or sharpness of an edge may be intrinsic to the objective description of an artefact but the nature of their similarity (attributes of designed by humans objects) leads to redundant information that does not provide clues for deeper understanding of why humans made, used and disposed them at particular locations. It is necessary to make an attempt to ascribe the symbolic roles each category of artefacts or structures has in the interplay between the so far known social realms (private, public and foreign domains in this case study) of the prehistoric communities.

A question arises as to how to define the trajectory of transition between empirical and symbolic facts? To a larger extent it remains subjective and the only way to objectivize it is to trace down the logic of evolution that transforms the empirical into symbolic meaning. As it was pointed out above in prehistoric human communication these trajectories can be outlined by the cycles of interplay between private, public and foreign domains of archaeological record that follow the logic of introduction of impossible worlds into the possible ones. This is the reason why it was chosen the artefact category of Neolithic clay figurines to mediate between the general symbolic meaning of artefacts from private and public domains. Although these artefacts are locally made and mostly kept within houses they have significance in the public arena as they represent the knowledge about the basic social structure (household) that characterizes all early farming communities in prehistory. Thus, the styles with which they are shaped and decorated have local, regional and supra-regional significance [11].

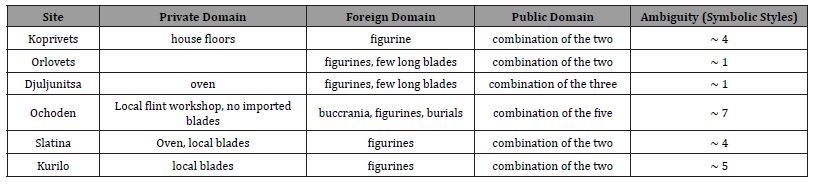

By following this logic of transition between empirical and symbolic facts it is possible to quantify and assign symbolic values relative to the number and semantic quality of the archaeological artefacts. For example, in the case of Kurilo site (Table 2) where excavations have never been done, the most numerous artefacts collected from the surface are the clay figurines. Although represented by a single category, the body shapes and decoration [11] of these figurines have at least five different ways of making. Hence the score of its symbolic value is 5. In the case of Slatina the shaping of the form and decoration of pottery seems somewhat simpler which makes a score of 4. The greatest diversity of artefact and structure categories but with less complexity in the ways of shaping forms and decoration is represented by the assemblages from the Ochoden site. The sum of these categories is five but their combination points to at least seven symbolic complexes so the score is 7. In the case of Djuljunitsa and Orlovets there is a simple decoration of figurines and few imported long blades so a score of 1 is assigned to their combination. Koprivets’ assemblages have simple figurine decoration, elaborated house floors and complex lithic techniques so a score of 4 is assigned to their symbolic combination. This symbolic classification cannot be considered as an exhaustive one because it contains dynamic categories of human communication and social interaction. This is why it is called ‘Ambiguity’ which summarizes the combination of symbolic complexes that emerge from the three socially distinguishable private, public and foreign domains that are empirically visible in the archaeological record.

Table 2: Approximate quantification of empirical and symbolic facts.

What particularity does this class of ambiguous symbolism possess that causes the great variability of the relationship established between empirical and symbolic facts? It may be sought in the nature of human encounters where two or more people meet to discuss their knowledge and skills for solving a particular task. Within such a scenario each of the participants tries to convince the others to believe that his/her arguments are the true ones. They enter into an epistemic basing relation which supposes elaboration of high-order symbolic language and expressions that involve diverse materials and concepts that are objectified through different materials and objects. On this ground it is expected that the variation of the symbolic facts will be greater than that of the empirical facts. This expectation is confirmed and visualized by the scatter plot of the presented above table (Figure 3) where the category of empirical facts changes only in two ways: it grows and declines. At the same time the category of symbolic facts (ambiguity in the chart) change four times; they decline, grow, decline and grow again. 4. Fractal-like behavior of the relationship established between empirical and symbolic facts.

The question arises as what is the nature of the greater variation of the symbolic facts? It concerns the relationship between the ‘pure’ belief represented by the absolute probability of reaching agreement between several parties in a given discourse and the conditional probability for reaching the same result but which represents knowledge based on established in practice experience. In order to approach and analyze this loose relationship it is better to replicate its basic features through simulation of the core principles of a general epistemic basing relation. Let us imagine that two or more people have to solve a given task and each of them puts forward his/her arguments and tries to convince the others that these are the true ones. They establish an epistemic basing relation that aims to harmonize their knowledge about particular issue. This relation is a complex one and involves several logical rules that govern the process of communication. It has been established that causality in any argumentation plays a central role in the process of establishing epistemic basing relation. Thus causation and human disposition can be understood in counterfactual terms which as a process take at least five steps for each Basing-History or Basing- Sustaining justification of an already established belief [12].

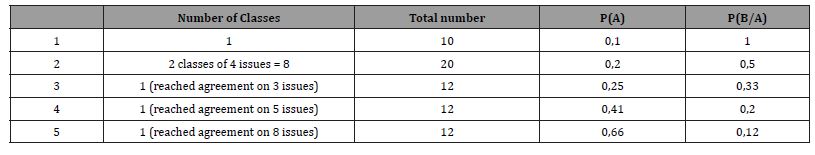

It is supposed that because of the different human dispositions and reasoning (through counterfactual expressions) the harmonization of the basic knowledge about a given issue will take considerable time. Yet it is not what in the formal knowledge is known as a recurrent relation which states that each point of a particular set (difference in opinions in this case) has to be visited in order to make a complete cycle of the process of harmonization of metaphors. Instead, it is sufficient that one or more dispositions or reasoning in the Basing-History or the Basing-Sustaining relations (ibidem) will appear as good enough for all the parties participating in a given discussion. In such a case it is plausible to assume that these knowledge harmonizing relations will establish loose relationships between different bodies of knowledge and human dispositions. In order to model their behavior in a dynamically changing environment it would be enough to consider an example of having three sets, each of which consist of 10, 12 and 20 different issues. Each of these sets matters in a given discourse of harmonizing intersubjective beliefs. There are two scenarios for reaching agreement in every one of these cases. Let us suppose that it is enough to reach agreement on 1 out of 10 issues of different opinions in order to reach an overall agreement in establishing practical belief. The absolute probability for reaching this “easy” outcome will be 0,1 while the conditional one (only if agreement on one issue has already been reached) will be 1. The next more difficult task will be what are the absolute and conditional probabilities for reaching agreement if it has already been established in one class out of two classes each of which consists of 4 issues out of total number of 20 different issues. In table 3 these and three more cases are presented. In the column ‘Number of Classes’ the number of conditional terms are given. The third column presents the total number of issues on which agreements have to be reached. The next two columns present the absolute P(A) and conditional P(B/A) probabilities respectively (Figure 4).

Table 3: Probability distribution of three different cases of reaching agreement.

This means that the local individual and community based process of harmonizing knowledge over a particular issue goes through a number of ‘meta-levels’. These ‘meta-levels’ may be defined as a higher order human cognitive practices that involve dispositions and reasoning of an epistemological basing relation. Although such a relation consists of few logical rules [12] the possibility for variation among different combination of these rules constitutes an enormous variety of practical options for reaching harmonization of knowledge and correct identification of metaphors. Thus the loosely defined hierarchical structures of ‘meta-levels’ remain relatively stable and exhibit little or no change when scaling up and down their hierarchy and over long periods of time. For example, the continuous persistence in preference of different lithic raw materials of two Neolithic communities living in less than ten kilometers apart from one another (Orlovets and Koprivets sites) shows that they both identify the symbolic difference between them imposed by this material expression. Such examples remain visible if this local pattern of preference of flint raw materials is scaled up to regional and supra-regional levels. At other sites there is an enormous range of degrees of acceptance and rejection of this type of symbolic material expression governed by the locally established hierarchies of meta-rules. The gradual establishment and accumulation of these meta-rules correlates with a kind of “symbolic outbreak” in late Neolithic communities which started to produce a great variety of symbolic objects and features.

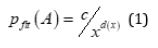

In order to check whether the scatterplot of absolute P(A) and conditional P(B/A) probabilities of such an epistemic relation has a fractal-like behavior (fat-tail distribution) it was fit by its corresponding values of P(A) calculated by scale dependent exponents’ assessment of the P(A) [13]. The difference between the values of conditional P(B/A) and those of the Scale Dependent Exponents (SDE) are sought to be minimized. The approximate assessment of the values of P(A) can be done by setting the following power expression.

The best fit between the values of P(A) and P_fit (A) determins the value of c to be equal to 0,1.The new values of x can be calculated from this expression (column 3 in table 4). The best fit is obtained by scaling dependent exponent.

Table 4: Calculation of scale dependent exponents and their fit with the values of P(B/A).

where α=0,8. In addition an overlay scatterplot of P(A), P(B/A) and P(SDE) values is made. It shows that the formal process of establishment of an epistemic basing relation behaves in a fractallike manner. A question arises as to what it means if the process of harmonization of different metaphors approximates a scale-free behavior. This result calls an intuitive notion of arbitrary process of assigning notions and values to material expressions made by conscious or unconscious crafting of prehistoric artisans [8]. There exist, however, limitations imposed on this process. They involve the interplay between the pure belief (extreme example of unconditional belief represented by the Absolute Probability P(A) in this case) and the belief conditioned by at least one proof (Conditional Probability P(B/A)). In Figure 5 it is visible that the values of conditional probability do not decrease sharply and form a long tail. From archaeological point of view this means that new issues from various discourses constantly come up into the spot of intersubjective interaction. They become objects of epistemic basing relations till they evolve into understandable for all parties harmonized metaphors. Thus the formation of ‘conditional beliefs’ is a long process that is qualitatively different from short-term formation process of ‘pure beliefs’ in intersubjective discourse. This theoretical standpoint allows to preview that symbolic facts are dynamic phenomena that appear as patchy, dispersed and overlapping spatial and temporal distributions.

An example of the spatial distribution of nephrite artefacts during the Neolithic and Eneolithic periods

According to the above theoretical considerations the expectation for spatial distribution of artefacts made of symbolic materials such as flints and nephrite would form loose temporary concentrations with wide sparsely populated periphery and tend to change their geographic position over time. An example that illustrates this dynamic behavior is taken from the publication of the so far identified nephrite artefacts in Bulgaria [14]. Indeed, the spatial distribution of the Neolithic nephrite artefacts differs from the Eneolithic one (Figure 6). The Neolithic nephrite artefacts form two loose groups. The first is in southwestern Bulgaria where there are no flint outcrops and all flint materials are imported from considerable distance. The second one is the Thracian plain where despite the abundance of local flint sources the Neolithic communities preferred the imported high-quality flint varieties. On this ground it is possible to make a conclusion that there is a certain spatial and symbolic correlation between the spread of the nephrite and high-quality flint artefacts. This conclusion is supported additionally by the fact that there are three other small occurrences of nephrite artefacts in northeastern Bulgaria where most of the sources of high-quality flint varieties occur. The Eneolithic distribution shows different pattern. In the first place the number of nephrite artefact occurrences is two times smaller than those in the Neolithic. Also, they are more evenly distributed than the Neolithic ones along the direction: Southwest – Northeast. At the opposite regions situated to the northwest and southeast there is an absence of nephrite artefact despite the occurrence of high-quality flint artefacts. If this rough regionalization of the occurrence of nephrite artefact is further scaled down a similar mosaic (presence/absence) pattern will emerge.

On this ground it is also plausible to assume that prehistoric settlements and the fields between them were populated by people practicing diverse crafts and skills. A traveler crossing a field would have the opportunity to turn at any step in a direction that most suits his/her needs to meet a particular person with whom to share some knowledge and learn something new about a particular topic. This new possibility of multi-directionality at small discrete steps forms densely populated cognitive places. The movement of a traveler through this network will depend on his/her interest of meeting particular learned and skilled people and the travel itself would outline the accumulation of the required knowledge so that this person to be able to take up a particular social position after his/her return to his/her own village. This way of acquiring diverse and abstract knowledge would be objectivized through tokens made of different symbolic materials such as particular flint varieties, nephrite and other materials. The acquired through these travels knowledge will enable a person to take a life-long social position (e.g. farmer with special knowledge about growing some plants, healer, leader in rituals, in festivities and guardian of religious and belief objects). The widening range of fluid personal identities based on knowledge and skills opens wide the possibility for more efficient than in previous times integration of new practices and human groups into the already established social networks [15,16].

Conclusion

The basic question that has been explored in this study is the conceptualization in a novel way of the population movement of the Neolithic communities in the eastern Balkans. The simulation of the quantified features of a likely epistemic basing relation reveals that the nature of the greater variation of symbolic facts has a scale free-like behavior. The general conclusion is that the longtail distribution outlines a boundary which qualitatively separates the knowledge based on proofs and the one based on ‘pure’ beliefs. The difference between them lies in the perceptual experiences and creation of mental models grounded on spatial differences along the discrete way of accumulation of knowledge (through travels). This means that the Neolithic travelers carefully planned and executed their journeys. The most general cause of these movements is the possibility for acquiring knowledge and skills that were objectified by various symbolic materials and objects. Once exposed to this complex perceptual experience travelers would have been able to take up higher social positions in their own communities and, most importantly, these practices allowed integration of other people into their social networks.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Leary J, Kador Th (2016) Movement and mobility in the Neolithic. In: Leary, J. and Kador, Th. (Eds.), Moving on in Neolithic studies: Understanding mobile lives. Neolithic Studies Group Seminar Papers 14: 3-20.

- Weber MJ, Grimm SB, Baales M (2011) Between warm and cold: Impact of the Younger Dryas on human behavior in Central Europe. Quaternary International 242(2): 277-301.

- Bentley AR, Price TD, Lning J, Gronenborn D, Wahl J, et al., (2002) Current Anthropology 43(5): 799-804.

- Tsonev Ts (2015) Archaeological approach to linear transformation of Surfaces (kriging, arcgis geostatistical analyst) and its potential for expanding archaeological interpretation. In: Papadopoulos C, Paliou E, Chrysanthi A, Kotoula E and Sarris A (Eds.), Archaeological Research in the Digital Age. Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology - Greek Chapter, Rethymno, Crete, Greece 6(8): 36-45.

- Hamilakis Y (2008) Time performance and the production of a mnemonic record: from feasting to archaeology of eating and drinking.

- Papa M, Halstead P, Kotsakis K, Bogaard A, Fraser R, et al., (2013) The Neolithic site of Makriyalos, northern Greece: a reconstruction of the social and economic structure of the settlement through a comparative study of the finds. In: Voutsaki S, and Valamoti SM (Eds.), Diet, Economy and Society in the Ancient Greek World, towards a better Integration of Archaeology and Science. Proceedings of the International Conference held at the Netherlands Institute at Athens, Leuven-Paris-Walpole, Ma: Peeters, pp: 77-89.

- Zlateva-Uzunova R (2009) Early Neolithic Stone Assemblage from Ohoden-Valoga Site, Building N 1. In: Ganetsovski, G. (Eds.), Ochoden an Early Neolithic Site, Excavations 2002-2006, Sofia, pp: 62-75.

- Layton R (1991) The Anthropology of Art. (2nd edn), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Bourdieu P (1998) Practical Reason. Polity Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Brewer B (2004) Realism and the nature of perceptual experience. NOUS 14(1): 61-77.

- Todorova H, Vajsov I (1993) The Neolithic in Bulgaria. Nauka I Izkustvo, Sofia, Bulgeria.

- Bondy P (2015) Counterfactuals and Epistemic Basing Relations. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly.

- Koleva, M. (2012) Boundedness and Self-Organized Semantics: Theory and Applications. Hershey: IGI Global.

- Kostov R (2013) Nephrite-yielding Prehistoric Cultures and Nephrite Occurrences in Europe: Archaeomineralogical Review.

- Feldman D (2015) Fractals and Scaling. ‘Complexity Explorer’.

- DAIS (2008) The Aegean Feast: Proceedings of the 12th International Aegean Conference / 12e Rencontre Égéenne Internationale, University of Melbourne, Centre for Classics and Archaeology, pp. 3- 19.

-

Tsoni Tsonev*. Least Cost Path Analysis and Conditional Perception of Prehistoric Travelers. Open Access J Arch & Anthropol. 4(1): 2023. OAJAA.MS.ID.000579.

-

Mythological, Ritualistic, Palaeolithic, Neolithic, Supra-regional significance

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.