Mini Review

Mini Review

Italian Studies and Graffiti, A Complex Relationship

Nicola Guerra*

Adjunct Professor School of Languages and Translation Studies, University of Turku ,Finland.

Nicola Guerra, Adjunct Professor School of Languages and Translation Studies, University of Turku , Finland.

Received Date: November 11, 2020; Published Date: December 15, 2020

Abstract

Despite its massive presence in our cities, the accusations of vandalism have caused scholars of Italian language and culture to shy away from the analysis of graffiti. Another factor might also have been a certain traditional elite perspective, to the detriment of ordinariness and of the everyday. In today’s society of widespread control of both physical and virtual spaces through capillary video surveillance and online monitoring which sees the usable spaces for dissent reduced graffiti art still represents an opportunity for free communication. Documenting and studying graffiti means participating in a work of democratization of linguistics, lightening it from the redundant burden of the classics, by the rigid reference to standard Italian compared to popular Italian (intended as a variety of speakers from the lower social classes characterized by poor social prestige), and by a certain purism that translates into fear of those evolutionary dynamics of the language that find representation in graffiti, not by chance creator and diffuser of numerous neologisms and linguistic contact.

Keywords: Graffiti; Italian studies; Street art; Italian linguistics.

Graffiti; Italian studies; Street art; Italian linguistics.

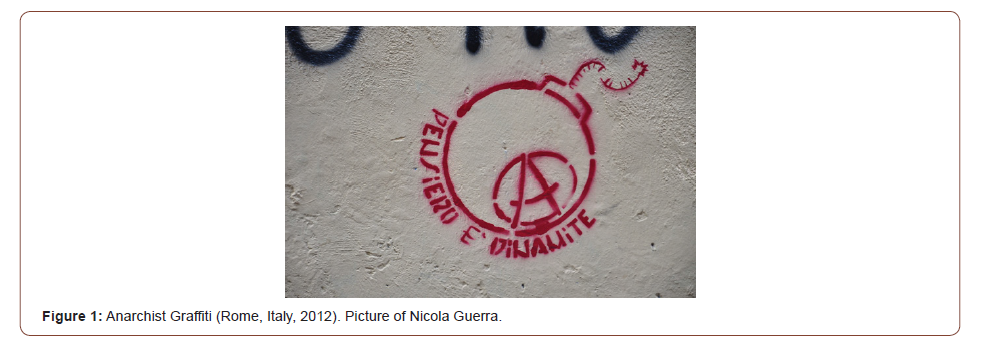

Both attributable to the birth of humanity and contemporary protagonist of the urban space, graffiti art does not find consensual definitions on either an artistic or a linguistic level. Despite its massive presence in our cities, the accusations of vandalism have caused scholars of Italian language and culture to shy away from the analysis of graffiti (Guerra [1], Guerra [2],Telmon [3], Radtke [4]. Moreover, this reticence to study them might also have been exacerbated by the fact that graffiti is used by subcultures that represent a counterpower to the organization of society. Another factor might also have been a certain traditional elite perspective, to the detriment of ordinariness and of the everyday Guerra [5] ,Zagrebelsky [6]; Williams [7]. Yet, a careful study of graffiti would help to follow the development of everyday language, to understand the dynamics of ‘young’ lingo, to grasp the sociolects of subcultures and metropolitan tribes, and to grasp the diametrical melting pot of the city, consisting of a kaleidoscope of communication channels in which orality and writing coexist and hybridize Guerra [1,5]; [2,8]. Figure 1. Anarchist Graffiti (Rome, Italy, 2012). Picture of Nicola Guerra.

An effective way of defining graffiti is to consider as such every intervention in which the semantic element, i.e. the set of graphemes, words and their articulation in texts, has the upper hand over the semiotic element represented by symbols, figures and abstractions, predominant instead in muralism Guerra [1,2,5] This definition takes into consideration how graffiti is a functional opportunity to blend linguistic and urban space Guerra [1]. As for the accusations of vandalism, we must not overlook the fact that contemporary graffiti have a counter-hegemonic essence, and although this is exercised by breaking the rules of urban decorum and disrespecting private property, it allows us to escape the stringent regulations required to access mass media communication classics such as newspapers and television. Therefore, graffiti can be seen as an exposed form of writing that communicates to the masses but not to the apparatus, because exercised in ordinariness and spontaneity, leaving the channels of high cultural and political control. It thus becomes a factor of communicative democratization. To put it in the manner of graffiti: «clean walls, silent people». Figure 2. Far Right Graffiti against techno-plutogracy (Rome, Italy, 2011). Picture of Nicola Guerra.

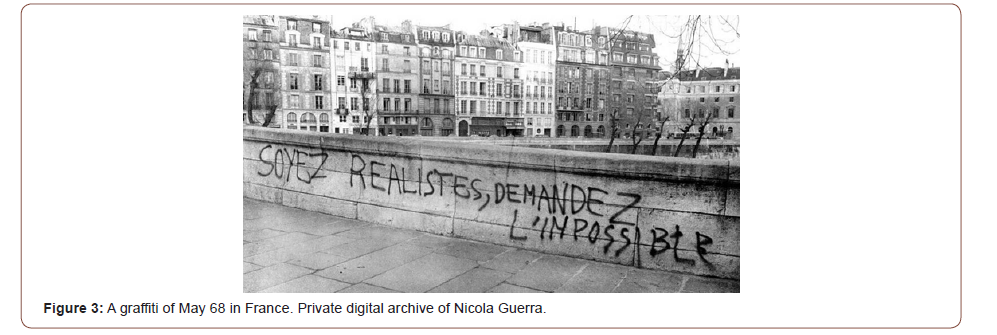

The walls speak

It is no coincidence that graffiti, together with paste-ups and poster-art, is the protagonist of the social and political revolt of May 68 in France Tesson & Barbery [9] Kugelberg and Vermès [10]; Rohan [11] and becomes an important channel of communication of the Protests of 1968 in Italy Guerra [8,12,13]. The post-war political scene in Italy, characterized by high technicalities and parliamentary equilibriums, was set apart by the use of a language generally known as ‘politichese’ (‘political-speak’), characterized by the tendency to mask rather than clarify contents, in which much-thought lexical choices gave a high register and a strong bureaucratic feel to political language Guerra [12,13,14]. If usually the overcoming of ‘political-speak’ is fixed at the year 1994, to the advantage of the ‘gentese’ (‘people-speak’) as a consequence of the political vacuum determined by «Mani Pulite», a more careful analysis shows how the reaction to it is antecedent to the events of the time and is undertaken by groups and political movements antagonistic to the system, starting from 1968 and for all the period known as Years of Lead Guerra [12,13]. Figure 3. A graffiti of May 68 in France. Private digital archive of Nicola Guerra.Figure 4. A Left Wing Graffiti with an Italian translation of the previous phrase from May 68 in France (Massa, Italy, 2020). Picture of Nicola Guerra. Those were years in which, also through graffiti, the use of a political language that moves from inhibition to participation and from cryptic to clear is asserted and consolidated, with the adoption of a linguistic register that maintains a certain intellectuality combined with usability and intelligibility, blending together instances of contestation, political propaganda, and civic sense within a high linguistic spontaneity Mori [15,16]. «We want it all», «Let’s take the city» - graffiti becomes an existential claim and affirmation of a different vision of the urban space, mirror of a new social order. If, too hastily, graffiti are considered works of a lower artistic level compared to murals, in which the semiotic element predominates and therefore the visual solicitation of the user, it is necessary to highlight how the artistic nature of graffiti is both linguistic and in the ability to condense, in the short time of realization and in the little space available, complex concepts that represent an ideology, a creed, a lifestyle Guerra [17,18]. The art of graffiti is mainly the art of language joined to graphic art in the choice of font and calligraphy. Both in the graffiti of 1968, more characterized by generational unity, and in those of the Years of Lead, pervaded by the dynamics of opposite extremisms fueled by social tension, the yearning for participation, clarity, social transformation and inclusion of those who were excluded from the strict logic of the party, parliamentary balancing acts, and a television dominated by control and censorship is loud and clear.

Documenting and studying graffiti means participating in a work of democratization of linguistics

In today’s society of widespread control of both physical and virtual spaces through capillary video surveillance and online monitoring which sees the usable spaces for dissent reduced Zuboff [19],Della Porta , Reiter [20] graffiti art still represents an opportunity for free communication. In the freely used and built urban space, graffiti offers an opportunity for expression to those who are excluded, in whole or in part, from institutional communication, as in the case of numerous heterogeneous subcultures: ultras, casuals, skinhead, hip-hop, rap, Hispanic and Latino gangs, political radicals, and ecologists. Documenting and studying graffiti therefore also means participating in a work of democratization of linguistics, lightening it from the redundant burden of the classics, by the rigid reference to standard Italian compared to popular Italian (intended as a variety of speakers from the lower social classes characterized by poor social prestige), and by a certain purism that translates into fear of those evolutionary dynamics of the language that find representation in graffiti, not by chance creator and diffuser of numerous neologisms and linguistic contact Guerra [1,2,5,8].

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflict of Interests

None.

References

- Guerra N (2012) Il graffitismo nello spazio linguistico urbano, la città come melting pot diamesico. Analele Universităţii din Craiova, Seria Ştiinţe Filologice Linguistică Nr 1-2: 89-92.

- Guerra N (2013) Lingua e città. Il graffitismo, lo stickerismo e le affissioni abusive come occasioni di studio delle dinamiche evolutive della lingua italiana. Mediterranean Language Review 20: 39-56.

- Telmon T (1996) Varietà In: Sobrero, AA (Eds.), Introduzione all’italiano contemporaneo. La variazione e gli usi. Roma-Bari: Laterza, pp. 93-149.

- Radtke E (1996) Varietà In: Sobrero, AA (Eds.), Introduzione all’italiano contemporaneo. La variazione e gli usi. Roma-Bari: Laterza, pp.191-235.

- Guerra N (2012b) Il labile discrimine tra spazio urbano e spazio linguistico. La città come dimensione spaziale costitutiva della variazione, del contatto e dell'innovazione linguistica. Il ruolo del graffitismo, del muralismo e dello stickerismo. Romance Languages: Italian and Sardinian Studies: 1-13.

- Zagrebelsky G (2010) Sulla lingua del tempo presente. Torino: Einaudi

- Williams R(1989) Resources of Hope:Culture,Democracy, Socialism.Londra eNew York:Verso.

- Guerra N (2013b) "Muri puliti popoli muti". Analisi tematica e dinamiche linguistiche del fenomeno del graffitismo a Roma. Forum Italicum 47(3): 570-585.

- Tesson P, Barbery B (2018) At the Heart of the Student Revolt in France. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

- Kugelberg J, Vermès P (2012) Beauty is in the street. A visual record of the May '68 Paris uprising. London: Four corners books.

- Rohan M (1988) Paris ' Graffiti, posters, newspapers and poems of the May 1968 events. London : Impact.

- Guerra N (2020) Il linguaggio degli opposti estremismi negli anni di piombo. Un’analisi comparativa del lessico nelle manifestazioni di piazza. Italian Studies (forthcoming).

- Guerra N (2020b) Il linguaggio politico di piazza della destra radicale e dei movimenti neofascisti negli Anni di Piombo. Mediterranean Language Review (forthcoming).

- Desideri P (1998) Metalanguage and rhetoric of attenuation in Aldo Moro's political discourse. In: Alfieri G, Cassola A (Eds.), The "language of Italy": public and institutional uses. Proceedings of the XXIX International Conference of the Italian Linguistic Society. Rome: Bulzoni, pp. 212-225.

- Mori L (2008) Gli anni Sessanta e la costruzione dell’identità linguistica europea. Sulla formazione della varietà comunitaria d’italiano.In: De Pasquale M, Dottoli G, Selavaggio M (Eds.), I linguaggi del Sessantotto. Atti del convegno multidisciplinare, Libera Università degli Studi “San Pio V”, Roma 15-17 Maggio 2008. Roma: Editrice Apes, pp. 531-544.

- Senf J (2008) Dall’inibizione alla partecipazione: l’apporto del Sessantotto alla glottodidattica. In De Pasquale M, Dottoli G , Selavaggio M (Eds.), I linguaggi del Sessantotto. Atti del convegno multidisciplinare, Libera Università degli Studi “San Pio V”, Roma 15-17 Maggio 2008. Roma: Editrice Apes, pp. 323-338.

- Guerra N (2020c) L'importanza e le modalità dello studio dei graffiti nel quadro generale dell'analisi delle sottoculture. Invited lesson at the University of Zagreb, Croatia.

- Guerra N (2020d) Il graffitismo come forma di espressione controegemonica e come occasione di documentazione e studio dell'innovazione linguistica. Invited presentation at XX settimana della Lingua italiana - istituto italiano di cultura di Zagabria.

- Zuboff S (2020) The age of surveillance capitalism. The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. New York : PublicAffairs.

- Della Porta D, Reiter H (2013) State power and the control of transnational protests. In: Olesen T (Eds.), Power and transnational activism. London: Routledge, pp. 91-110.

-

Nicola Guerra. Italian Studies and Graffiti, A Complex Relationship. Open Access J Arch & Anthropol. 3(1): 2020. OAJAA.MS.ID.000551.

-

Finely-carved, Beneath, Pontius Pilate, Jewish

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.