Research Article

Research Article

Investigating the Role of Perceiving and Applying Genre Characteristics in the Process of Source Text Reading and Target Text Production

Lara Burazer*, PhD

Assistant professor, Department of English, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia

Lara Burazer, PhD, Assistant professor, Department of English, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia

Received Date: October 26, 2022; Published Date: December 01, 2022

Abstract

In this paper, we focus on the comparison of the processing of text between translation students and law students, who are expected to be exposed to different linguistic content. The postulated thesis that, due to their greater exposure to legal texts, law students would demonstrate better grasp of perceiving and applying macro-textual characteristics, while students of translation would excel better at micro-textual features is confirmed. The findings are supported by the analysis of the answers provided by students in a short questionnaire, as well as by the analysis of the features employed in their translations. Another important factor in text processing is highlighted in the paper - the concept of expectations. Processing of linguistic content is based on previous experience with texts, whereby expectations are created, which are either confirmed or refuted through further experience with texts. If confirmed, the expectations are strengthened and may even grow into norms, if not, new expectations are formed. Based on these findings, we were able to conclude that the appropriate use of macro-textual elements may be critical to achieving quality of the text and it is therefore crucial to teach them in translation programs, ensuring that through an appropriate amount of exposure to specific content students will form relevant expectations in accordance with which they will subsequently produce acceptable (target) texts.

Working Hypothesis

The aim of the investigation presented in this article was to reveal which characteristics of text genre readers of the genre recognize and remember in the process of reading a text, and subsequently apply in the process of producing a text of the same genre. The processes of reading and producing a text in this case refer to the two basic activities of a translator: reading of the source text and the production of the target text (the translation).

The investigation was based on an example of a legal text in Slovenian (a part of an employment contract - specifically an article on trade secrets) which was given to 39 students (28 of which were students of translation studies and 11 law students; cf. also section 3 below for a more detailed description of the student groups) to read and then answer a short question on what they were able to recall about the text. We postulated the following thesis:

‘In the process of reading a specific text genre the reader will remember some macro-textual (e.g., informativity or register) as well as micro-textual features (e.g., specific terminology or lexicogrammatical patterns), depending on their prior experience with texts of the particular genre.’

The starting point of this investigation was to emphasize the double-tier translator’s processing of texts for translation, who in the initial stage of the process acts as the reader of the source text, and in the consequent ones as the creator of the translation or the target text. What served as a starting point was also the importance of the double-tier processing of text on two separate and at the same time closely interwoven levels of the text: at microand macro-textual levels. One of the goals was the discovery of the relevant translation competences required to identify these dualities, therefore, the study led to the investigation of the effects of focusing attention on the analysis of the text at these levels and verification of compliance with the findings of the analysis in the production of the target text.

However, since translation - in reference to its essence of reading and writing texts - is primarily a form of mediating in communication between people, it is essential that one does not neglect its principal agent or actor - translator, as by conducting research in the field of translation, we verify at least some possible ways in which the reader understands the text, which is reflected in the production process of the target text by the translator.

Theoretical Background

The importance of involving the reader in the process of adopting the text is not a new approach to the study of linguistic communication. Already in the seventies of the previous century certain theories emerged which emphasized the importance of involving the reader in the interpretation of meanings, such as reader response theory (Rosenblatt [1], Iser [2]), and a whole series of authors in the field of functional approaches to the study of language and content of text analysis, for example: de Beaugrande 1977, Brown and Yule [3], Kintsch [4], Halliday [5,6], Van Dijk [7], which have contributed significantly to the modification of approaches in translation studies, mainly by shifting attention to investigating the supra-sentential level of texts, the study of the text as a whole.

Textual approaches and the Reader Response Theory shed light on the importance of processes associated with the individual’s previous experience with texts. Linguists, such as Brown and Yule (1983: 59), have pointed this out extensively, which drew attention to the importance of “local interpretation” of the text, the interpretation of meaning of the text within the relevant factors in their environment and in the context of their general knowledge about the world, which also includes experience with texts.

In this paper, we therefore focus on the comparison of the processing of text between translation students and law students, who are expected to be exposed to different linguistic content. Due to their greater exposure to legal texts, we expected that law students would better detect and identify macro-textual characteristics, while students of translation would detect and identify micro-textual features better, except the group with the textual pretreatment. This thesis was checked against the answers provided by students in a short questionnaire immediately after the experiment, as well as by the features in their translations, which is in line with the theory of discourse analysts (e.g., Cumming and Ono ‘[8]), stressing the importance of the frequency of text when processing a text. The final phase of the experiment involved an evaluation of the translations by experts from various fields. We expected the results would render the extent to which appropriate use of macro-textual elements may be critical to achieving quality of the text.

Another important factor is highlighted in text processing: expectations. Expectations are a concept which has been increasingly emerging in the recent decades in the fields of linguistics and translation theory. Processing of linguistic content is based on previous experience with texts, whereby expectations are created, which are either confirmed or refuted through further experience with texts. If confirmed, the expectations are strengthened and may even grow into norms; if not, new expectations are formed.

According to Van Dijk-a [7], in the process of communication we look for patterns which we as a community share with other members of society (the so-called ‘assumption about normality of the world’). Our expectation in the study was that law students would adopt the text for translation as appropriate to the genre of legal texts and properly transfer the recognized genre characteristics of the legal texts from previous experience to the translation. The most obvious of such macro features in the selected text was the level of formality.

The factor of previous experience with texts at this point connects with memory characteristics, where an important role is played by the translator’s short-term and long-term memory. It was therefore interesting to our study that the first three tested groups were composed of students of translation, which are supposedly not exposed to professional legal texts daily, and we therefore assumed that their “legal discourse” was not in a stand-by mode (cf. Kintsch [4]). On the other hand, these students are supposedly exposed to English texts daily, which led us to the conclusion that it would contribute to a higher level of readiness of their general foreign language content and skills. Of course, this does not mean that lawyers have their legal expert content, and translators their linguistic content constantly in the stand-by mode, but that the communicative situation triggers the relevant expectations which are then in the stand-by mode [9-11].

Contrary to this, we assumed that the students of the fourth group, law students, are exposed to expert legal texts daily, and we therefore expected that when reading the text for translation, expectations in relation to language and discourse characteristics of legal texts would be triggered and in the state of readiness. This would mean that they would find the text for translation more familiar in content than the students of translation. On the other hand, law students are supposedly not exposed to foreign language (in our case English) content daily, which could cause problems when processing the text for translation, which was in English.

In Toury’s words, socio-cultural factors subconsciously affect the translator’s behavior, but are extremely difficult to study. Thus, in Gutt’s words, people in certain social groups share thoughts, so it is possible to consider the receiver of the text, at least indirectly. As the creators of the target text, translators can build on this premise and anticipate the expectations of their target audience. It is also necessary to consider the relevance principle, which has been extensively researched by Sperber and Wilson [9]. If this principle is properly observed in the course of communication, with an infinite number of possible inferences, we assume that it will help the receiver extract those messages that the communicator had in mind. As the relevance principle is based on the ‘cost-benefit’ relation, we follow the principle of minimal energy input for text processing with the greatest possible benefit to the reader [12-15].

Experiment

Description and Method of Investigation

The investigation involved 39 students, of which 28 were from the Department of translation (University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Arts), with no more than 3 or 4 years of translation experience into their mother tongue within the university, and 11 law students with practically no translation experience, but with considerable experience with the legal text genre. The task was a translation of an article on trade secrets from an employment contract into their mother tongue - Slovenian (cf. appendix 1).

The students of the Department of Translation, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, were all junior and senior year students who had had translation subjects in all previous years of study, theoretical (such as Translation Theory) as well as practical (Translation Practice Classes from and into the selected foreign language, translation modulus of various text genres), where they received instruction on translation tools and various translation approaches. In this respect the translation students held an advantage over the law students in terms of certain expert translation knowledge, while the law students held an advantage over the translation students in terms of recognizing the legal genre on account of them having been exposed to numerous legal genre texts in the course of their studies (the legal group was composed of students of all 4 years of study).

The Reasons for the choice of students and choice of text genre

The reasons for the choice of students where mainly expert ones since the investigation is based on comparison of different ways in which experts from different fields (in this case the fields of translation and law) process an expert non-literary text. The processing of a legal text would therefore require expert linguistic and translation studies knowledge as well as expert legal knowledge.

The reasons for the choice of the legal text genre were several. On one hand there were several expert reasons, such as:

a) Given the choice of countless text genres, the legal genre represents a relatively unfamiliar area. By this we mean that people are generally vaguely familiar with legal texts; they have come across them but have not been closely familiarized with them (this is, of course, a general impression based mainly on subjective experience of the author with teaching text genres to students as well as on direct response of translation students at the Department of Translation (Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana), especially in English Text Formation Classes). Incidentally, the general expectation is that students will have a formed opinion about the genre. (This expectation is based on teaching experience of the author as well, specifically on student response - whenever given the choice, they would choose to discuss any other text genres to legal, such as promotional, scientific, journalistic genres, even horoscopes and medical texts were preferred to legal genre.)

b) There seems to be a general opinion among students that legal texts are ‘difficult’ or ‘complex’. Judging by their descriptions, they seem to perceive legal texts as dull and too complicated at times (this finding is based on the results of a short survey among the students of translation and those from the English language Department, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana).

c) This is a specialized genre with recognizable characteristics, nevertheless people often seem to think that being familiar with legal terminology will suffice to become an expert in the field (as is the case with many ‘technical’ fields). However, experts in the field of writing as well as translating such expert texts are usually aware, based on prior experience with texts, that being familiar with terminology alone will not suffice, on the contrary, becoming an expert in a particular field requires additional knowledge, linguistic (specific microas well as macro-textual discourse characteristics) as well as expert subject field knowledge.

d) This type of discourse enables the researcher to isolate a section of the text for the purposes of investigation, which plays an important role in facilitating the experiment. One of the many textual characteristics of the legal genre is that cohesion is not achieved through the use of reference items, such as pronouns, ellipsis or substitution, but rather relies on achieving clarity through the use of repetition. Therefore, a section of the text can easily be separated from the rest without reducing the level of clarity, or the level of understanding textual details. In most cases, on macro-textual level legal text are organized into wellrounded short units, such as chapters, articles, and paragraphs, which results in better clarity as well as independence of individual parts of the text in terms of textual characteristics.

Group structure

For the purpose of the investigation, the selected students were organized into 4 groups: group1, group2, group3 and group4.

Group1 was a control group consisting of 9 senior year translation students. Group2 was an experimental group consisting of 10 senior year and one junior year translation students. This group was subjected to micro-level legal terminology treatment. Group3 was also experimental, consisting of 8 senior year translation students, subjected to a treatment with macrotextual characteristics of legal texts. Group4 was another control group consisting of 11 law students, of which 2 were freshmen, 2 sophomore, 5 junior and 2 senior year students.

In the two control groups the students were from the Faculty of Arts (University of Ljubljana) and the Faculty of Law (also University of Ljubljana). They were not subject to any pretreatment within the experiment; they only received instructions for the translation task (see appendix 2). The reason for choosing to have two control groups from two different faculties was that we were aiming for a comparison of the level of acceptability of translations/ texts between students with a strong background in linguistics and Translation Studies on one hand, and those with a strong background in law and legal discourse on the other. In examining the results of the experiment, we were then able to investigate how previous knowledge of linguistics and TS and the law reflects on the level of acceptability of translations.

The remaining two groups were experimental and therefore subject to pre-treatment. In one of the two groups, an extensive discussion of legal terminology in both English and Slovene was carried out prior to the experiment. The students had to do a few exercises on legal terminology (see appendix 3), such as completing the text with appropriate prepositions (collocations, phrases) and choosing the appropriate terminology (multiple choice gap fill). While doing these exercises, the students also encountered certain terminological expressions, which were later on used in the translation text (for instance: disclosure, trade secrets, third party).

In the other experimental group, we carried out a discussion about legal discourse, specifically focusing on textual features of legal texts (see appendix 4) prior to the experiment. Special emphasis was placed on general discourse characteristics of the genre, such as impersonal style of expression, decontextualization, use of certain grammatical structures, modality, and the like. However, in the course of this discussion they did not encounter any of the specific legal expressions that could benefit them in the translation task. The purpose of the intended difference in the selected treatments was to direct the students’ attention toward the specific micro- as well as macro-level textual features of the genre. This way we could investigate the effects of focusing on specific (micro- and macro-textual) aspects of legal discourse on the quality as well as acceptability of translations.

Immediately after the treatment, both groups were given the selected text to translate (see appendix 1). All groups received the same text for translation, and they were all given 60 minutes for the task, which was more than enough time for the short article on the protection of business secrets of the employment contract.

At the end of the translation task, the students were asked to answer one question, which was: What do you remember from the text that you have just finished translating? Our expectations were that the students who had been directly exposed to the treatment with legal terminology prior to the translation task would mostly remember the legal terms used in the text, irrespective of the language. In accordance with the latter, the students from the other experimental group, who were exposed to the treatment with the textual features of the legal genre would remember large portions of the text or more general information on the text as a whole.

We have classified the collected answers into four categories. The first category represents the macro-textual features that relate to the overall understanding of the text or the informativity on the inter-sentential level (cohesive) level, for example the message of the text. The second categories are the micro-textual features, which relate to the use of lexical grammatical structures, for example specific grammatical patterns and terminology. The answers that relate to other forms of text perception on micro-textual level, such as the use of specific structures, the use of dictionaries and other translation tools, were also classified in this category.

The third category of responses were summaries or interpretations of the text for translation, where the students in their own words loosely described the content of the text, while not strictly following the sequence of the information given in the text and not using technical terms to describe the content, but rather describing the content in the form explanation or interpretation.

The fourth category were translations, as some students in their description of the contents very carefully followed the source text and presented it in a way that is characteristic of translation rather than summary. This means that they used appropriate Slovenian structures and terminology corresponding to the relevant English structures and terminology used in the text for translation.

The reason for ranking the students’ responses in four categories described above is that we were primarily looking at differences in responses regarding the perceived characteristics of the text, which were originally divided into two basic categories: micro and macro textual features. However, in the review and analysis of the responses it seemed reasonable to distinguish those answers which contained more concise passages from those which were presented in the form of bullet points or where it was merely a list of terms. However, it is important to stress that the category of summary or interpretation of the text is regarded as one of macro-textual categories, because the summary represents the student’s perception of the text message as a whole, and it is therefore justifiable to classify it at the macro-textual level, not at the level or micro-textual features or individual lexical units (words or phrases). This interpretation was also taken into account in the interpretation and analysis of the responses received, so we classified summaries or interpretations as perceived macro-textual features.

In the category of translation, the classification of responses into the category of macro or micro-textual features was harder. On the one hand, we can speak of the interpretation in favor of micro-textual characteristics, because the student had in the production process of translation also considered the following: phrases, single words, sentence structure, search for translation equivalents in the target language, and the like. On the other hand, the translation can be interpreted in the context of the perception of the reader at macro-textual level as perception at the level of the full text is necessary for the production of an adequate translation. In categorizing responses into micro or macro-textual features we placed translations into the micro-textual category because students clearly did not manage to extract the message from the text for translation, but they wrote down the entire text or most of it as an answer.

Drawing a demarcation line between micro- and macrotextual elements

When we talk about micro-textual level language investigation, it usually refers to language study out of context, on a lexicalgrammatical level. It is, therefore, not unusual to deal with legal terminology without relying on any specific text. Or you can deal with the use of the passive voice at the level of general syntax differences between Slovenian and English, for example, without having to cite concrete examples.

On macro-textual level, the investigation of concepts is always in context, and it addresses their specific functions in the co-text. Strict separation between micro and macro textual elements can pose a problem, as it is in the macro concepts, such as register, where we are looking into the use of certain linguistic elements that out of context, as separate words, act as micro-textual elements. Treatment of modal verbs, for example, is possible at microtextural level, but they can be treated at the macro-textual level as well. We can, for instance, consider the impact of the use of respective modal verbs to create the tone of the specific text. Of course, with reading, understanding, and interpreting the text we are always dealing with a complex process, which operates simultaneously on two levels, both micro (in conjunction with the individual concepts, details of the text) as well as macro-textual (in conjunction with the expressiveness of the text which the reader develops through a hermeneutic process of text perception).

In general, the distinction between macro and microtextual levels of text represents a controversial area if we take under consideration the fact that perception, interpretation and understanding of lexical units representing micro-textual level is closely linked to perception, interpretation and understanding of the context or text, which represents macro textual level of language study. For the purposes of this study, we decided to simplify the interpretation of these two categories, which is in line with general practice in the field of education and teaching in reference to development of text features recognition skills. In the context of these programs (Translation Studies and Law) students encounter these categories particularly in the programs of the Department of Translation, specifically in the courses on Text Production, Discourse Analysis, Word Formation, Idiomatic and Stylistics, where the study of text is approached at both the level of individual lexical units, as well as at the level of the text as a whole. Within the framework of programs at the Faculty of Law, students encounter legal terminology in a foreign language in the second year of study. The subject of general or macro-textual content in a foreign language is not in the curriculum, therefore it would be difficult to say that law students receive instruction on the macrotextual features of legal texts in a foreign language. Their program does, however, include a number of subjects with specialized legal content, where students are likely to familiarize themselves with macro-textual features of legal texts in their mother tongue.

Structuring the Data

The data compiled with the questionnaire, where the students only had to answer the question ‘What do you remember about the text that you have just read?’ were structured into two basic categories:

a) The category of macro-textual characteristics relating to the general understanding of the text or its informativity on supra-sentential - cohesive level (e.g., the text message; this category also contains examples of students providing a whole summary of the text); and

b) The category of micro-textual characteristics relating to the use of lexicogrammatically structures (e.g., specific grammatical patterns or terminology; here we included also the examples where students produced a translation of almost the entire text - this indicates that the student was not able to process the text on a supra-sentential macro level which would have resulted in merely the summary of the text; the student was evidently processing the text on the micro level which resulted in producing a detailed translation).

Result of the Investigation

Based on the collected answers to the questionnaire and collected translations of all groups of students, we examined the hypothesis raised.

When reading the selected text genre, the reader (generally speaking) remembers some macro-textual features (e.g., the informativity, register) and some micro-textual characteristics (e.g., specific terminology and other lexical-grammatical patterns), in line with their previous experience: the second group of students of translation studies will remember more micro-, while the third group will remember more macro-textual elements.

On the basis of the replies to the questionnaire on perceived characteristics of the selected text genre, we were able to check hypothesis, which refers to the impact of the pre-treatment intended to draw the attention of the students to the topics discussed during their reading activities.

Analysis of Result

The first part of the results of the experiment relates to the analysis of the responses to the question about what the students in particular groups remembered in the process of reading the selected legal text. Analysis of the responses revealed a wide range of interesting findings.

With the first group, which was the control group, we did not have specific expectations relating to the design of the experiment. We did, however, have lay speculations that students of translation studies may be more inclined to focus their attention on both the general text characteristics as well as the terminology, unlike the law students who were expected to focus more attention on the message of the text.

Given the fact that all the students of the first group were in the last year of the translation study programme, we could assume that they had already received formal instruction in both language areas (discourse analysis in the subjects of Word Formation and Idiomatic and Stylistics; grammar and other linguistic content in the subjects of English grammar, Grammar Practice Classes, English Language Practice Classes, and other).

Thus, we have observed in the analysis of their responses that two students replied to the question about what they remembered from the text with a brief summary of the full text, which is in accordance with the focus and the substance of the courses that the students attend mainly in the first and second years of their study program (particularly in Translation Practice Classes). Due to the fact that our experiment was designed as a translation practice test, it is realistic to conclude that the expectations of students were similar to their previous experiences with Translation Practice Classes, where it is normally expected of students to either summarize or translate the text in accordance with the instructions given in each case.

Three students responded with a text that would partially correspond to the category of summary and partially to the category of translation, which means that some parts of the text were clearly specified (which is characteristic of translation), while some interpreted (which is characteristic of summary). We can look for possible reasons for such combination of summary and translation in either unclear instructions, diverse understanding, or interpretation of the task by students, or even in the lack of skills or knowledge of students who accidentally wandered from summary into translation or vice versa.

In response to the question of what they remembered four students wrote down several items of English legal terminology that had remained fresh in their memory, only one student wrote down Slovenian legal terminology. In this case the interpretation of the responses requires we look back at previous experience of the students, particularly in subjects with linguistic content, where students are often required to read the text at the terminological level. Such a task essentially requires of students to search for new or unfamiliar lexical units that are being considered at the level of meaning interpretation; it involves finding synonyms, searching for cases of illustrative use, collocations, and the like. Since our text for translation was a professional text with appropriate terminology, it is realistic to expect that some students did not understand certain terms, on account of which certain terminology remained fresh in their memory; or that they remembered certain words because they are rarely used in the texts they commonly discuss in class, which is why they seemed more interesting. The table below shows the structure of the responses of students from the first group tested: (Table 1).

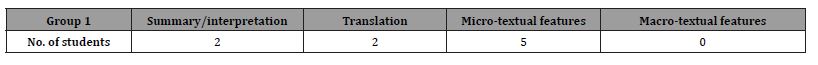

Table 1: response structure of Group1

In view of the fact that we decided to treat summaries or interpretations of the text provided by the tested students as macro-textual treatment of the text, it is possible to interpret the results obtained as follows: the students’ perception of the text was mainly at the micro textual level, as evidenced by the 5 reported cases of citing terminology and 2 cases of text that would fit the category of translation, which also points in the direction of text perception being on a detailed level, rather than at the level of loose interpretation using their own words. We would, therefore, speak of having reported 7 out of 9 cases of micro-textual perception and 2 cases of macro-textual perception.

These results may also speak in favor of one of the reasons for the selection of the text for translation, which are listed above in Section 3.1, namely the thesis that there is a prevailing opinion among students (perhaps even among people in general) that professional texts and language used in them differ from everyday language or from the more commonly discussed genres of texts in everyday life, particularly on the level of terminology. Therefore, there is a common belief that if you acquire the terms that typically occur in certain specialist texts, then it somehow follows that you have mastered the discourse of a particular professional field overall.

The perception of the text at a level that is higher than mere terminology demands a certain level of maturity in a student, which is achieved by acquiring the relevant content in the academic program, as well as via experience with text genres. This maturity is reflected above all in the perception of the function of texts in real-life situations, in knowing that general understanding of the text by the reader, as well as accepting the text as adequate, both at the level of sentence structure and single lexical units as well as at text level, results in certain responses of the target reader; it results in successful or unsuccessful completion of activity performed by the author of the text, for instance. The success rate of the author of the text with the target audience is dependent on the perception of the text as adequate at the level of both macro-textual as well as micro-textual features of the text.

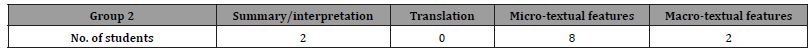

Table 2: response structure of Group 2

In the second group, which received the pre-treatment with legal terminology, one student responded to the question by stating Slovenian terminology, 4 students indicated a few English expressions and the modal verb SHALL, 2 indicated the general content, 3 mentioned collocations and structures, but without giving any specific examples, one mentioned the use of dictionaries and grammatical structures, and 1 complained about incomprehensibility of the structures with ‘WHICH’ and cited specific words (violation of secrets, kršenje skrivnosti). The results were categorized as follows: (Table 2).

In the case of the second group, the results blatantly confirm our hypothesis that the pretreatment in the form of terminology exercises would largely draw the attention of the students to the micro-textual level of the text. Of course, it is debatable whether the terminology exercises played a decisive role in directing their attention or did the exercises trigger the students’ expectations that the answers should be terminologically colored. Perhaps their expectation was also that we were testing their short-term memory, and they therefore invested particular effort into listing a whole series of terms from the given text. Regardless of the numerous possible interpretations listed above, the results indicate that the majority perceived the text primarily at the level of micro-textual features.

One-third of the students still stated macro-textual features or summaries of the text in their responses, which is due to the deliberate vagueness of the question (What do you remember from the text?) and again due to their prior experience with similar exercises in translation, where they were probably expected to demonstrate a deeper understanding of the text. And this is precisely the category including summaries and descriptions of the individual parts of the text ‘using one’s own words.

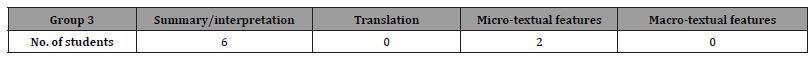

In the third group, which had been subjected to the pretreatment with textual characteristics of legal texts, one student stated legal terms pogodbena določila, poslovne in tržne skrivnosti, delavec/predsednik uprave, razkritje, tretja oseba, pogodba o zaposlitvi, zakon o nelojalni konkurenci). 6 students wrote down general content, where we recorded a number of errors in both English (2 students) as well as in Slovenian versions (4 students). One student did not answer the question (this student is not included in the table). One student mentioned the ‘terms’ but stated none (this is included in the table under the category of microtextual characteristics). The results were categorized as follows: (Table 3).

Table 3: response structure of Group 3

These results again support our thesis that the students who received pre-treatment with macro-textual characteristics would mainly perceive those in the process of their translation task and those are the features that would be reflected in their answers to the general question. So, with the exception of two students, they did not state individual terms in their answers, but focused their attention on understanding of the text or parts of the text as a whole, which they then described using their own words.

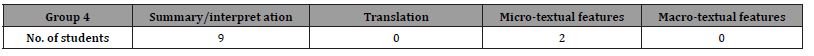

In the fourth group, 9 out of 11 law students wrote a summary of the text as a response to the question; they were mainly focusing on the interpretation of the text, which they defined as a combination of a non-compete clause and provisions on trade-secrets. One student paid specific attention to Article 2 of the text. We have also noticed focusing on terminology (podjetje, menedžer, varovati zaupne informacije, prenehanje delovnega razmerja). Some students (2) remembered mostly terminology, both Slovenian and English (provisions, business and trade secrets, unfair competition, disclosure, possible translations of the word ‘manager’: direktor, upravnik, poslovodja, delavec; writing the word ‘company’ with a capital letter). Here are the results: (Table 4).

Table 4: response structure of Group 4

Although the fourth group only included law students, the results are comparable to those we have seen with students of translation, which were given the pre-treatment with textual features. This information is quite telling, given the fact that in the description of the experiment we established the hypothesis that law students would in the process of reading the text focus their attention to the text as a whole, which means that we anticipated that they would focus primarily on understanding the message of the text, the text’s informativity and the function the text ‘performs’ in real life. For the most part, the law students tested did not go into detail about the meaning of individual terms (this is probably rooted in the belief that law students are supposedly much more familiar with these expressions than students of translation).

This confirms our thesis that students of translation will focus primarily on micro-textual and macro-textual linguistic elements, for their primary focus of study within the department programme is the study of language. One of the main curricular objectives of their study programs is to be able to produce an appropriate and acceptable translation from their mother tongue into a foreign language or vice versa. This means that they are tackling the challenge of mastering their mother tongue in addition to two other foreign languages, which all need to be mastered at all levels for successful completion of study. On the other hand, law students encounter language in legal texts at different levels, especially at the level of understanding of the message of the text, rather than on the level of specific linguistic elements. Also, the objectives of their study are slightly offset from the micro-level and are focused more on understanding, explication, and interpretation of the text, which represents a macro level of language.

Discussion

The expectations that we included in the thesis were checked on the basis of the collected answers from students of all tested groups and to the question that we asked at the end of the experiment: Please describe briefly what you remember from the text you have just translated. The question was deliberately designed so that the students’ responses would involve a wide range of possible interpretations. Given the fact that the students were exposed to different pre-treatments prior to the experiment, we did not want to lead them in answering the question.

With the purpose of obtaining responses from the students which would be as neutral as possible, we were aware of the fact that it is extremely difficult to predict human expectations: how our words and actions affect the way human expectations are formed or triggered.

We received very diverse answers, which were roughly divided into the categories used in the tables above (summary / interpretation, translation, micro-textual features macro-textual characteristics), reflecting the diversity and unpredictability of human nature.

In formulating scientific questions in the context of the thesis we had to rely on the presumption / hypothesis that students in general are a focused group; in our case the translators are more focused on monitoring the linguistic features when reading a text, while lawyers are focused more on the interpretation of the meaning, the actual function that the text is expected to perform in the real world, in real communication.

This assumption is also based on the observation that the process of acquiring the skills to translate technical texts within the context of translation studies is focused on gaining experience with specific technical texts and learning terminology, which is often considered separately from the text as a whole, while law students deal with legal texts primarily at the level of their communicative functions such as acquiring information and knowledge which are the basic social functions of discourse. Students of translation are, on the other hand, also burdened by the fact that dealing with technical texts at the level of textual features is subject to testing their translation skills in both mid-term and final exams. Perhaps it is for that reason that it seems that they are easier to deal with on micro-textual level, when it comes to the treatment of individual structures or vocabulary, which is somehow more manageable - it seems that there is a finite number of possible matches. When reading texts at macro-textual level, it seems that, given the diversity of human language use and comprehension, the number of possible translations is infinite.

Equally ungrateful are the assumptions about the language in which respondents would answer, given that they were dealing with two languages in the experiment. Despite the fact that all stages of the experiment were conducted in Slovenian, that almost all the tasks were set out in Slovenian, excluding the text for translation (the second group of students also had some of the tasks of terminology in English, students of the third group were given one text in English), some students responded in English. Perhaps the choice of language was affected by the following:

a) The fact that the researcher was from a foreign language department

b) The fact that some tasks were in English (although some of the law students responded in English as well)

c) The fact that they had to deal with the field (students of translation), which they generally find unfamiliar in their mother tongue, at the level of terminology as well as discourse features.

It is worth pointing out that it is very difficult to distinguish between macro and micro-textual characteristics; dealing with one without considering and mentioning the other is probably not even possible, which is why the present research employs simplified categories, which are at close inspection undoubtedly partly intertwined.

In the process of categorization into micro- and macro-groups we discover quite a few gray areas that fall partly in one and partly in another category. We usually speak of micro-textual characteristics when the reference is to single words, short lexical units and the like, but it is again difficult to determine the precise length of lexical units that still falls into the category of micro-textual features. At some point this length coincides with one corresponding to the category of macro-textual features. In addition, macro-textual features consist of micro textual elements. One such example would be the use of pronouns or the definite article, which operate on macro-textual level, but are themselves micro-textual elements. The same treatment could be applied to ellipsis and substitution, where we discuss individual cases by emphasizing their cohesive functions at the level of the text.

Our final conclusion at this point is that the thesis has been confirmed. This is supported by the fact that, unlike other groups, the third group in the majority wrote summaries, which means that their attention was directed to the full text, rather than individual parts, even though not many responses were recorded in the section of macro-textual characteristics; it just means that these features were not specifically and terminologically highlighted or named, but it is evident from the submitted summaries and interpretations that they did observe them.

Conclusion

The study was based on assumptions derived from everyday experience with teaching students of translation and evaluating their translations, which showed some problems in employing macro-textual features. From this perspective, the comparison between translation and law students was particularly interesting, since the latter are expected to be the experts of legal discourse. This led to the thesis that they will find it easier to recognize legal discourse features of the selected text and take them into account in the process of translation, even if they lack experience in translation.

The survey results are largely consistent with this thesis. In line with our predictions, the students who received the treatment with legal terminology prior to the experiment were much more focused on micro-textual characteristics, which is evident from the questionnaire, as well as their translations. While the law students and the group which was subjected to the discourse treatment prior to the experiment focused more on macro-textual features and employed them in their translations - they mentioned them in their replies in the questionnaire.

The survey results led to some important conclusions. Among the first was the realization that language as a subject of study is an elusive category, especially in cases where we have to classify parts of it into various categories. In our case it was a demarcation line between micro- and macro-textual characteristics, which is not an easy separation, such as one between verbs and nouns, for example, but rather a complex distinction between linguistic categories, which are intimately intertwined. Formally speaking, macro-textual features in fact consist of micro-textual elements, but they differ significantly in the treatment of uses and functions within a text. With macro-textual characteristics we are referring to those linguistic features of the text which contribute to the register, which is the category that contributes to the development of the genre. Strict separation between these two categories is therefore a virtually impossible task.

One of the main problems of linguistic scientific research is also the fact that language is idiosyncratic and formed in accordance with an individual’s life experiences, which are largely diverse. This results in significant differences in the use and interpretation of linguistic content. In research and evaluation in particular we may therefore rely solely on established norms, which are not binding for the language users, but only act as guidelines for acceptable language use.

The research findings suggest that language cannot be meticulously distributed into categories, so it follows that both micro- and macro-textual features should be carefully addressed and taught. However, it is important to emphasize that those micro-textual features - and their appropriate use - acting on macro-textual level (such as specific terminology) construct the register of the text and indirectly shape the genre features. And it is acceptability of register and genre that triggers a response on the acceptability of the whole text in the target audience. From this perspective, one may assume that the target audience is more forgiving to unacceptable solutions of the author on microtextual level, rather than at the level of macro-textual features, as unacceptable micro-textual solutions will not affect the register and genre characteristics of the text and the message will be left intact or more acceptable at textual level.

Experience shows the opposite, however, namely that people are much more likely to notice errors at micro-textual level, where the reference is to the use of ‘wrong words or grammar mistakes, while macro-textual features are perceived purely on an intuitive level when ‘something seems off’, or ‘does not sound right’.

In the past, the teaching of language content, in translation studies as well, focused primarily on micro-textual features and words. With the emergence of discourse analysis, the tendency for changes in the approaches to teaching of translation studies also emerged. Discourse linguistic content at the level of text is increasingly at the forefront, but it is nevertheless necessary to point out that even in translation studies the micro level of language should not be neglected if we are aiming to achieve a high level of acceptability of translations as texts.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Rosenblatt, Louise (1976) Literature as Exploration. (4th edn)., The Modern Language Association of America, New York.

- Iser, Wolfgang (1978) The Act of Reading. Baltimore, MD (Eds.), Johns Hopkins University Press, USA.

- Brown, Gillian, Yule, George (1983) Discourse analysis. In: Teun Van Dijk (edt.). Discourse as Structure and Process. London: Sage 35-62.

- Kintsch, Walter (1988) The role of knowledge in discourse comprehension: a construction - integration model. Psychological Rev 95(2): 163-182.

- Halliday, Michael A K (1978) Language as a Social Semiotic. Longman, London, and New York.

- Halliday, Michael A K (1996) Functional Grammar. Arnold: London.

- Van Dijk, Teun (1977) Text and context. Longman, London.

- Cumming, Susanna, Ono, Tsuyoshi (1997) The study of discourse. In: Teun Van Dijk (Eds.), Discourse as Structure and Process. Sage, London, pp. 1-34.

- Sperber, Dierdre, Wilson, Dan (1997) Remarks on relevance Theory and the Social Sciences. Multilingua 16: 145-152.

- Beaugrande, Robert Alain de (1996) The story of discourse analysis. In: Teun Van Dijk (Eds.), Introduction to Discourse Analysis. Sage, London, pp. 35-62.

- Burazer, Lara (2011) Zaznava in upoštevanje besedilnih značilnosti ob prevajanju ter njihov vpliv na sprejemljivost prevoda. Dissertation text - Faculty of Arts, Department of translation, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

- Gutt, Ernst August (1991) Translation and relevance: cognition and context. Blackwell, Oxford, Uk.

- Toury, Gideon (2000) The nature and role of norms in translation. In Lawrence Venuti (Eds.), The translation studies reader. Routledg, London, pp. 198-211.

- Toury, Gideon (1999) A handful of paragraphs on 'translation' and 'norms'. In Christina Schaffner (Eds.), Translation and norms. Multilingual Matters, Philadelphia, pp. 9-31.

-

Lara Burazer*, PhD. Investigating the Role of Perceiving and Applying Genre Characteristics in the Process of Source Text Reading and Target Text Production. Open Access J Arch & Anthropol. 3(5): 2022. OAJAA.MS.ID.000574.

-

Lexico-grammatical, Macro-textual, Legal discourse, Decontextualization, Micro-textual

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.