Research Article

Research Article

A Multi Theory Approach for Studying Presumed Ritual Pottery - The Stirrup Spout Bottle as a Case Study from the Pre-Hispanic Andes

Detlef Wilke1* and Ina Wunn2

1Dr. Wilke Management & Consulting GmbH, Wennigsen, Germany

2Seminar for Religious Studies, Leibniz University Hannover, Germany

Detlef Wilke, Dr. Wilke Management & Consulting GmbH, Wennigsen, Germany.

Received Date: September 28, 2019; Published Date: October 23, 2019

Abstract

Anthropological art and culture theory, neurobiological cognition theory, comparative religious studies, form-function analysis as well as archaeological and pictorial scenic context information are used to identify the hitherto unknown functionality of the stirrup spout bottle, a predominant pre-Hispanic vessel type at the Peruvian north coast, and to allocate this and further spouted bottle types to its presumed cultural domain: the religious-cosmological realm. The inferential limits of ethnographic analogy and of traditional art historical approaches of artifact interpretation are considered, as well as the caveats of meta-level inferences from archaeological finds without written context, and how to deal with the epistemological ambiguity of material produces as results of human intentional acts. Ethnographic, ethnohistorical and the limited archaeological evidence points to ritual consumption of hallucinogenic drugs in the pre-Hispanic Andes, which the spouted vessels may have been involved in as containers and administering devices. However, in the absence of residue analyses and without proof of psychoactive alkaloids or its degradation products, even an occasional use of the spouted bottles as containers for drug storage and administration stays hypothetical.

Keywords:Anthropological art theory; Culture theory; Religious studies; Ethnographic analogy; Scenic context analysis; Ritual drug consumption

Introduction

“Ritual Pottery” was the special theme of the 51th International Symposium on Ceramic Research, Sibiu, Rumania, September 23-28, 2018, where selected topics of this paper have been presented [1]. In medieval and modern Central Europe with foremost Christian tradition ritual objects made from clay were extremely rare, mainly for the generally quite restricted use of ritual paraphernalia in Christian rite, but also for the preference of more valuable raw materials like precious metals. By contrast the likelihood of encountering ritual objects in prehistoric, small-scale, non-Western societies with presumed close nature-environment related religious-cosmological worldviews is much higher, whether made from stone, metal, clay, or perishable materials.

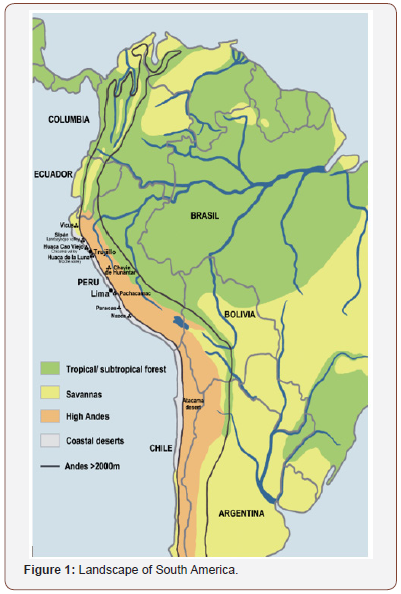

As a concrete example for the challenges the out-group observer is faced with, when trying to identify suspected ritual items in past non-written cultural contexts, the “stirrup spout bottle” is taken, which in pre-Hispanic Peru and adjacent countries has been archaeologically proven for almost 3000 years (Figure 1). Valdivia and Mayo-Chinchipe style bottles in Ecuador date to about 2000 BC, and Ecuador is considered as the origin of the bottle form [2]. The term is artificial and refers to the strange arc and spout outlet of the vessel, which reminds of a colonial Spanish stirrup. In early 20th century German “Altamerikanistik” the term “Gabelhalsflasche”, literally “fork neck bottle”, was used, but has later been abandoned in favor of the English/Spanish term (“botella asa estribo”).

The vessel type together with its specific surface decoration, spout form and other stylistic features is virtually the “Leitfossil” [3], one of the most important diagnostics find categories in Peruvian archaeology [4-8]. Its complex form is achieved by using molds for individual parts of the vessel and composing them to assemble the complete bottle, thus a reasonably complicated craft item [9]. However, its specific function and role in ancient individual and social life is unknown. Its form with the forked neck/ spout looks strange, “it must be symbolic” (cf. [10]). The stirrup spout bottle is often referred to as a “symbol of status” or “symbol of power” [11,12], thus addressing secondary functionality without knowing its primary function. If field archaeologists are asked for the content of the stirrup spout bottle as an obvious container, the answers vary from water, chicha (alcoholic corn fermentation product), no material content at all, to “we do not know”, which is the most reliable response, whereas the still vague mentioning of hallucinogenic potions is exceptional [13].

Highly decorated stirrup spout bottles have predominantly been excavated as funerary gifts in supposed elite tombs and in special rooms of ritual/ceremonial/administrative centers [14], but simple, less elaborate specimens have also been found, making its use by ordinary people and peasants living in the rural hinterlands of urban settlement agglomerations likely as well [15]. At least there is no indication that ownership of the vessel type as such was socially controlled or restricted. If the social status of its owners was inferred by either contemporary spectators or by modern observers, then probably from the artisanal elaboration of the artifact and the amount of high quality, fine ware ceramics and metal items deposited as grave goods, respectively, but not from the mere possession of the object type itself. Most of all stirrup spout bottles acquired by museums and private collections in the 20th century, both in Peru and worldwide, were derived from looting, and its archaeological find context is unknown.

Latest since the 1980s archaeologists acknowledge that stirrup spout bottles and other decorated fineware pottery were not just funerary offerings, since sherds are also found in household contexts, though at far lower ratio compared to utilitarian pottery remains [15-20]. Most probably, if not deposited in caches, special architectural features, cult centers and sanctuaries [14], intact stirrup spout bottles have been passed into the tomb of its respective owner as his/her personal property being indispensable in the afterlife. Moreover, if special artifacts had intrinsic power (see below: animated objects with agency), there may have even been an obligation to preclude such items from unauthorized, dangerous use by burying them together with the deceased person. Indeed, finds of intact stirrup spout bottles in domestic urban contexts are very rare [21].

Ritual vs. Ceremonial and Profane Utilitarian Objects

The primary task of this study is to evaluate whether the vessel type of the stirrup spout bottle is a ritual item, a ritual paraphernalia. The term “ritual” therefore needs to be defined (cf. [22]). In religious studies a ritual is a set or sequence of proscribed acts in a rite. Ritual and rite are almost synonymous. Typically, the sequence of the individual acts, if it is not just one, is not deliberate but binding. Rituals are thought to be founded in myth and tradition, established by ancestors or predecessors of the actual performers. The practitioner may be a ritual specialist or an ordinary person, elite member or non-elite, performing the ritual in private space or in public, with or without others joining him as a group of performers. In an ethnographic/anthropological context a ritual is more than a mere habit, performance or play, but has a serious purpose and task. Hence there is an interface between ritual and magic, since both have in common that the performance must be exactly followed in order to guarantee its intended outcome.

Ritual is also considered as a regular (re)enactment, recall and (re)presentation of religious traditions, concepts and myth. In such cases the aspect of efficacy may be less prominent. Ritual may then have an interface with ceremony in order to perform a certain socio-political task, e.g. establishing and reinforcing political power in public performances/spectacles [23-25], and reinforcing the ideological coherence of the social group, similar to Durkheim’s [26] Marxist notion of what religion is good for in society. When ritual works as (re)enactment of religion and myth, it may be a very stable cultural phenomenon with invariant, almost anachronistically looking elements, providing culture historians with long term insights into continuity and change [27]. Indeed, the colloquial definition of rite includes both religious and other solemn performances, and thus ceremonies without obvious religious aspects as well. According to this broader definition of rite, ritual objects or ritual paraphernalia would then be part of both the sphere of the religious-sacred and of the mundane-profane.

Such broader ritual term predominates in the social sciences, where any repeated, patterned or coordinated doing by more than one individual is called a ritual (e.g. Interaction Rituals: all encounters between individuals have a ritual-like quality, [28]). Even more colloquially social scientists talk about the daily attendance of TV news as a ritual, or about a “breakfast ritual” individuals or households are performing [29]. The coffee pot would then be a ritual item, which obviously does not make much sense for the purpose of prehistoric artifact analysis

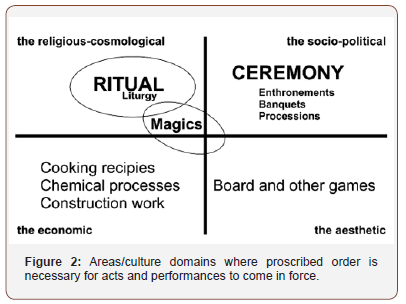

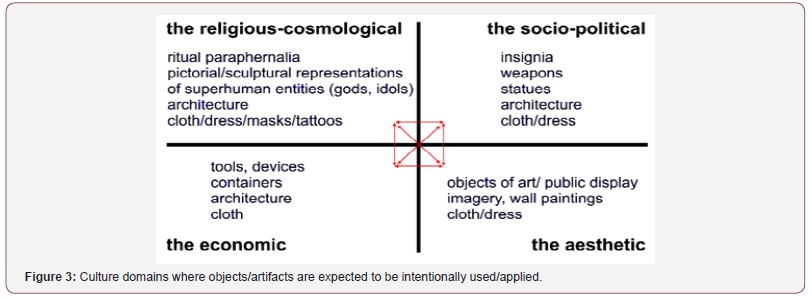

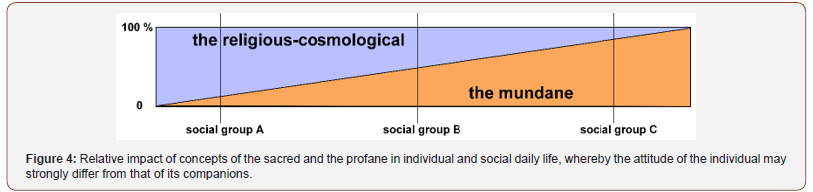

In archaeology, particularly if scholars have a strong educational background in the social sciences, the term is sometimes specified as “religious ritual” [27,30], which others may call a pleonasm. As Whitehouse [10] pointed out in this context, terms are used either with a range of meanings which are never made clear, or with a definition so broad that virtually no aspect of human behavior is excluded. In the following the ritual term is restricted to proscribed or standardized performances in the religious-cosmological domain, with its purpose located in this domain (e.g. worship of superhuman entities, matters concerning the afterlife) or beyond (e.g. divinations, safeguarding of food and fertility, hunt and war output). By contrast if executed in the socio-political realm without strong religious-cosmological context such performances will be referred to as ceremonies, and in the profane/mundane/ economic domain as processes, procedures or routines (Figure 2). Unconscious and unintentional, regularly repeated acts are considered as habitual behavior or habits. These narrow definitions use dichotomies for mere analytical purposes, and do not deny the many interfaces and gradual moves of observed phenomena from one domain to the other (Figures 3&4), nor the contingent incompatibility of Western binary analytical thinking with the more holistic cosmological concepts of small-scale societies [31,32].

As far as colloquial language is concerned it is important to recognize that in a post-enlightenment attitude scholars from the late 18th to the early 20th century have used terms like ritual, magic and symbol with pejorative, discriminating, and derogatory connotations, ritual and magic being irrational or superstitious and its outcome without causal reason [33,34]. “Symbolic” as an attribute was often used to describe a proforma or “as if” act with a perceived, but nonreal output. The term “symbolic” is still in frequent use as an attribute for the description of a scene or an artifact which the modern out-group observer is not familiar with, but concludes that the strange looking thing must be highly loaded with ideological content/value, or that rituals and rites have more (attributed) meaning/content than to be expected from the mere sequence of acts. The term “symbolic” is then used metaphorically for supposed, but undisclosed intentional meaning. By contrast, however, the agent/performer has intentions when performing a ritual, but does not necessarily attribute meaning to an act, like meaning is attributed to a word symbol which without such attribution would have no meaning at all. Following ethnographer Alfred Gell’s anthropological theory of art [35] the symbol term is almost totally dispensable in anthropological art and artifact description. Indeed, it is better restricted to linguistics, speech and writing, and a few other true symbol systems like those used in mathematics and chemistry.

The colloquial term “art interpretation” is adopted from literary studies, where it is used as a method for detecting nonobvious, hidden connotations, meaning, thoughts, intentions and messages of the author regarding any expression, character, and happening described in the text. Umberto Eco [36] has propagated the unrestricted, free interpretation of literary texts, a kind of speculation, which is well accepted in many disciplines like philosophy, and in general on behalf of the religious believer, but is exactly the opposite of what is needed in anthropological artifact study. Therefore, the conventional term of art interpretation is avoided here, and replaced by the narrow term of artifact description. The intentions of the agent, the artifact maker/ user, and the conclusions which a contemporary in- or out-group onlooker of the artifact may have drawn, are tried to be enumerated as a set of hypothetical inferences from form, shape, content, and context, which can be ranked by probability (see further below).

Whitehouse [10] has distinguished six types of ritual objects- Sacra (the actual objects of worship), Votaries (representations or stand-ins for people making offerings to deities or other supernatural beings), Offerings (food items or objects intended for the deity’s use or glorification), Objects used in rites (items of equipment utilized in religious ritual), Grave goods (objects placed with the dead), and Amulets (personal possessions used for ritual purposes, often worn on the body). The category of amulets can be extended by other body ornaments and modifications, namely tattoos [37], cloth, dresses and masks (Figure 3). For an anthropological study of ritual objects, the importance of ritual, magic, worship, and offerings as measures for managing human life with limited access to cause-effect based, scientifically fortified survival strategies cannot be overestimated.

Cultural Domains

A key issue in archaeological theory debate is the question whether immaterial religion can be inferred from (supposed) ritual objects or from archaeologically detectable traces of (supposed) ritual performances [27,38]. Criteria to allocate archaeological findings to either the domain of the religious or the profane then get even more important, particularly for the study of pre-literate time periods and other contexts without written documentation. Even if such distinctive criteria would have consensually been defined, its identification in the archaeological record may be difficult or almost impossible. Any simple tool, instrument, or vessel can be designed for a particular function in a cultural domain (Figure 3), but the agent may also situationally shift its use from one domain with one functionality to another domain with the same or different tasks (e.g. “ritual domestic wares” [15] ). Most funerary offerings on a global scale through time, e.g. the various ash and bone containers, ollas, pots, urns, have probably not been destined by the potters as specialized (sacred) grave goods, but were made and used for an ordinary utilitarian task, and only later in its use-life, and demand driven, these artifacts have been applied in another context and domain [10,39].

Other objects may no longer be practically applicable for a utilitarian purpose due to its inappropriate material composition, size, unstable or excessive decoration, but its utilitarian descent is still obvious from its characteristic form/shape. Rather few types of objects may have unique form/shape features which are unparalleled in any mundane context and may have been specifically invented and further improved in a ritual context to assist a religious-cosmological task. Wooden snuff trays and tubes for nasal inhalation of powdered hallucinogenic plants for divinatory purposes are such a class of implements, for which no utilitarian application can be imagined at all, and which is thus one of the few undebated types of ritual objects in South American ethnography and archaeology [40-43] (Figures 3&4).

Anthropological Background Theories

Anthropological culture theory

By necessity anthropology tends to overestimate the role of the individual when ritual, religion, cosmology and its broad socio-cultural implications are studied, whereas sociology tends to overestimate the role of the group when describing its sociopolitical function. Ritual is one of the infinite self- and otherreferential mental and physical interactions of the individual which constitute the anthropological culture theory of ethnographer Franz Boas [44]. Boas’ anthropological culture definition is fully in line with agency theory, where the agent is the intentionally acting individual [35,45]. Artifact making in the sense of Boas is a cultural interaction, namely the interaction of the agent with his/ her material environment (stones, clay, plant fibers etc.). Artifacts as well as speech and writing are products of cultural interactions, but artifacts as such neither are nor do they constitute culture [44]. Hence in a terminologically puristic sense there is neither “visual” nor “material culture”, but only visual, auditory, sensory, and material results and produces, respectively, of human cultural interactions. Basic survival measures like eating, drinking, dressing for cold protection, as well as propagation are biological self- and other-referential interactions, which only get the status of cultural interactions, when intentional variant formation increases beyond the mere evolutionary habitual needs

Anthropological art theory

Ethnographer Alfred Gell has developed an anthropological art theory for what he called “ethnographic art” [35]. His core thesis is that art is an index of social agency. It is neither surprising nor new that art and artifacts as results of human intentional acts (cultural interactions in the sense of Boas) can serve as an index/indicator of exactly this intentional activity. As stated by Alfred Schütz [46] a cultural object cannot be understood without referring it to the human activity from which it originates. If applied to archaeological material remains the theory acknowledges the primacy of the anthropological quality of art and artifacts vs. its mere diagnostic use as surrogate markers for relative chronology of its ancient makers/users, as sources of inference on its ethnic and cultural affiliations, or as “material indices of ideological programs” [15], whether religious-cosmological or socio-political. Drawing inferences from artifacts on meta-level aspects of society and culture, but without knowing the primary use and role by and for its ancient makers/users would be speculative. Using artifacts as indicators of rank, status, gender, occupational specialization or for distinguishing between profane and sacred spaces makes only sense after prior confirmation of its indexical appropriateness in the socio-cultural context. Besides the analytical tools which Gell has developed he stated that ethnographic art, i.e. non-industrial, non-Western art, cannot be adequately described and understood in terms of the intentionality of its original makers/users when applying modern Western aesthetic art concepts, nor as being symbolic, nor as an intentional, active information system, nor being narrative and readable like a text [35]. As Nicholas Thomas pointed out in his preface to Gell´s Art and Agency, “it is axiomatic for many scholars, and indeed in much common-sense thinking about art, that art is a matter of meaning and communication. Gell, however, suggested that art is instead about doing” (Thomas in [35]: ix, emphasis original).

Neurobiological cognition theory

Another important background theory for studying both religion and artifact making is neurobiological cognition theory. In the late 1960s Humberto Maturana developed the so-called constructivist cognition theory [47,48]. Whereas cognition theories historically fall into the domains of psychology and analytical or epistemological philosophy, Maturana’s neurobiological theory of thought and awareness/consciousness describes the mechanistic aspects of human cognition, which meanwhile have been principally confirmed by experimental neurophysiology and neural imaging. In its most provocative thesis the theory points out, that the brain has no direct access to the outside world but is a “closed”, “autonomous” organ within the human body (the notion of the brain as an “autopoietic” [autonomous self-replicating] system as originally stated by Maturana & Varela [49] was a terminological mistake). In contrast to our common perception (in its colloquial sense) we do not see, hear, and feel “directly”, but the incoming sensory signals received by the sensory organs are triggering biochemical and cellular neural reactions, from which the brain is constructing complex internal cell and tissue-based networks, the mental or thought constructs - visual, auditory and sensory mental images/representations. A perceived perception is not a “real” perception in the sense of a naïve “direct” realism [50,51], but sensory perception and the construction of awareness are two different neuronal operations. The neuronal constructs generating awareness and consciousness are clearly distinct from the sensory signal input receivable or effectively taken from outside phenomena but provide internal mental representations of the outside world which are extremely fast and sufficiently reliable and accurate in order to let the individual survive in an even harmful environment. Though the mental representations are constructed, they are by no means arbitrary, as the postmodern notion of “narratives” may suggest, and it would not make much sense to try to deconstruct them.

Neurobiological cognition theory has numerous important conceptional implications for culture studies, but only three of them are referred to here

(i) There is no collective (social) consciousness as the “consciousness of consciousnesses” which Emile Durkheim has stipulated in his idealistic view of society [26]. Similarly, “group feeling” is a colloquial expression for the awareness of the individual being part of a group and sharing this experience with others. Rather consciousness is a highly individual phenomenon, and the obvious harmonization of consciousness and the resulting joint worldview among group members is the outcome of numerous revolving selfand other-referential interactions, including those of education and learning in early childhood which makes youngsters familiar with the meaning of terms (word symbols in a syntax), with concepts, actions, and things [52]. Neurobiological cognition theory therefore confirms Boas’ focus on the individual as the actor/interactor/ agent in cultural anthropology, whereas it contradicts Geertz critique of Boas and Malinowski “attempting to interpret cultural materials as though they were individual expressions rather than social institutions” [53]. Neurobiologically speaking “mind” is the cover term for awareness, consciousness, experience, knowledge, and memory, which are neuronal-neural constructs generated and conserved in the brain by biochemical and cellular reactions. These constructs are triggered by external stimuli and modulated by the body’s own hormonal-endocrine metabolites as well as through psychoactive compounds/drugs, creating intentions, desires, volition, as well as notions, tasks and strategies, whether conscious or unconscious.

(ii) Neuronal constructs and mental representations can also be generated without any actual sensory input, e.g. by recalling previous states of consciousness (memory) or by unconscious brain activity (dreams). The brain is also in a position, to establish mental neuronal networks representing new concepts, ideas, forms, shapes etc. without any outside prototype and signal at all. In the mundane-profane sphere such prototype-less mental representations are known as inventions and “fantasy” of all kinds, in the religious-cosmological domain as mental imagery of non-visible supernatural/superhuman entities and its properties and deeds. Mental representations without sensory input of external prototypes can be created by recombination/reshuffling of established neuronal constructs, but the degree of creativity is strongly enhanced in states of trance and upon psychoactive drug consumption [54].

From comparative religious studies and ethnography we know that in small-scale societies living in close contact with its natural environment, supernatural/superhuman entities, which must be contacted/interacted with for safeguarding human welfare and survival, frequently have animal or plant [55-59], sometimes also geomorphological shape/guise [60]. Even if such social groups recognize supreme beings like a creator god, these entities are typically thought to be silent/absent after the creation act has been completed (“deus otiosus”, [61]). Such deities are therefore not responsible for human welfare, and thus not contacted or worshiped concerning the daily needs of the religious believers. On the other hand, addressing unknown superhuman entities indifferently as deities or gods (or beasts, devils and demons), probably mistakes the religious-cosmological concepts of many small-scale societies, particularly when strong Western connotations of the term God are involved [61].

Concerning the religion of the “Mochica“ at the Peruvian north coast (ca. 100-800 CE), Larco Hoyle [5] stated that they have developed the old feline deity of the north coast into a supreme deity, Ai Apaec, with fanged mouth and wrinkled face. He had adopted the term Ai Apaec from the vocabulary of Padre Don Fernando de la Carrera working in the diocese of Trujillo, Moche river valley, who in the early 17th century has drafted a bilingual confession manual for his fellow clergy. In the grammar chapter Fernando de la Carrera [62] took as an examples chicopaec, for Spanish el criador, and aiapaec, Spanish el hacedor, both literal translations of “the maker”, “the creator” or Christian God into the local contemporary language. Though Rowe [63] strongly opposed to the adoption of the linguistic construct of Fernando de la Carrera by Larco Hoyle for describing ancient “Moche” religion, the term Ai Apaec established for some time as denomination of therianthrope beings with fanged mouth. Inca religion as the beliefs of a more stratified society, and in line with Bellah’s [64] developmental concept of religion paralleling the level of socio-political complexity [65,66], comes closer to the worship of god-like entities [67], but there is still a lot of Western/ Christian/Spanish prejudice in the terminology applied by the early chroniclers [68].

The superhuman entities to be interacted with are frequently thought as animated, i.e. having mind and intentionality, again including geomorphological structures like stones, mountains, springs etc. Whether an object like an idol in the awareness of its beholder is just physical material or has intentionality is a matter of brain operations, and the qualities of the object may change situationally. If animal beings are depicted, or animal beings with human features and vice versa (therianthropes), they may represent such animated superhuman entities, figurativepictorial representations of mythical ancestors with animal guise, or performers reenacting myth and generation tales. Following Hultkrantz [56] the worshiped animals are typically derived from the immediate environment of the social group but are stably preserved over generations even after a move of the group to a different ecological zone, where the particular species/genus may no more be present. In case of the Andes a tribe formerly living in the eastern tropical slopes of the Andes with the jaguar as the mightiest animal in the forest can be considered, which afterwards moved to the high Andes or to the coastal desert valleys, where only small felines live, but still continues with the imagery of the large animal with its characteristic black spotted skin.

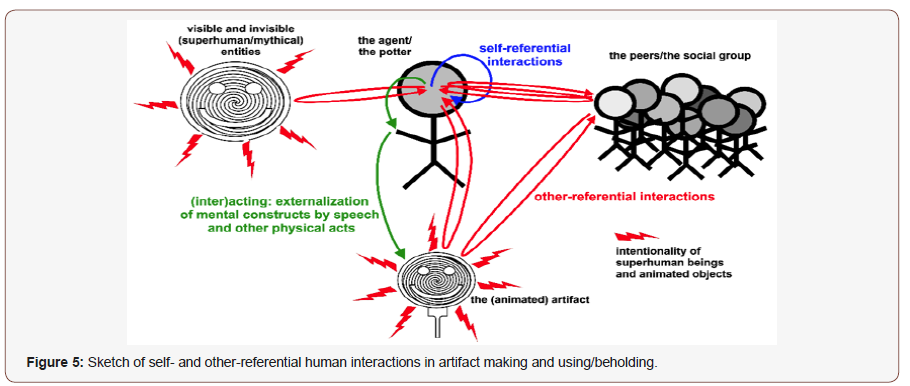

(iii) Neurobiological cognition theory also provides us with a mechanistic explanation for artifact making, i.e. the generation of mental templates of visible and invisible entities in the brain/ mind of the agent/artisan (e.g. the potter) and its externalization by materialization. The culturally most important externalization of mental representations is by speech acts and writing, respectively. If the artisan is for instance modelling an animal figurine based on a visual prototype from his environment, this is not an act of direct copying of the prototype, but a fast, repeated other-referential interaction between his/her brain and the material, mediated by hands and fingers as the tools for forming and shaping (Figure 5). The template of the artifact is not the physical prototype, but its mental representation, regardless whether a visible animal or its memory exists or whether there is no visible prototype at all. The shaping process is one of many sources of variant formation of form and shape of artifacts, i.e. depending on the technical skills of the artisan in properly externalizing his mental template in material form.

In neurobiologically quite accurate terms the Spanish captain D. Bernardo de Vargas Machuca [69] reported in the context of coca, jopa [vilca, Anadenanthera spec.] and tobacco chewing, when the Indians lose their consciousness and the devil talks to them: “This is what people tell about the Indian hechiceros [sorcerers], mohanes [medicine men/shamans] and santeros [makers or sellers of religious images], representing them [the idolatrous prototypes] in thousand different figures, and in the form, which appears to them, they make the figure from gold, clay or cotton, which they worship with reverence (translation by the first author).”

Supportive Methods

Iconography and the narrative approach

As will be exemplified below, the pictorial and low-relief decorations of stirrup spout bottles and other fine ware pottery are an important source of information about the use context of the stirrup spout bottle in non-funerary contexts. In many of the scenes therianthrope actors or participants are depicted, which may represent superhuman beings, enactors of such entities in ritual scenes, or actual human beings exhibiting the depicted qualities, features and characteristics by genealogical descent or by profession. For instance, a ritual expert/shaman may have derived his power from an ancestral custodian or predecessor, a primordial shaman [70-72]. It is the advantage of artifact making that the artisan can represent the entities as they are, whereas the participant in a ritual or ceremony is restricted to body paintings, dresses, head masks, and insignia to outline such superhuman or ancestral qualities.

However, without written context, the characters of such beings are difficult to identify, since figurative-pictorial representations cannot be read like a text [73,74]. Reading pictures and paintings like a text is at best a metaphorical expression, as “reading a landscape like a book” is a literary trope. Art historian Ernst Gombrich has cited Pope Gregory the Great (540-604 CE) who acknowledged the didactic potential of images like church murals: “Painting is to those who cannot read what letters are to those who can” [75]. Unfortunately, the Pope´s analogy is very weak since the illiterate needs first to listen to the biblical words in order to grasp the sense of the represented pictorial scenes and the names and characters of its participants, whereas the reader gets this abstract content information immediately from the text. Illustration, therefore, does not substitute speech or text, nor is it possible to “decipher” the text from its iconic representation [76]. Rather the term iconography would better be restricted to true iconic writing systems. Similarly, text illustration performed by an artist who has visual knowledge or imagination of the actors and the scene, provides distinct additional form and shape information on the subject matter, which is difficult to describe by word symbols in syntax.

Thus it is more than questionable whether Moche style pictorial scenes (see below), which are an important context source, can be considered as graphic scripts composed of semasiographic signs establishing a syntax like discursive system, as suggested by Jackson [77], nor to infer a system of proto-writing from outside pottery mold marks and incisions [78], which rather look like potter’s marks for sorting the numerous molds, the artisan had in use at the same time. Supporting the notion of a “visual culture” it was stated that Moche imagery is more than just pictorial representation, but contains value-laden icons, elements with iconic meaning [77]. However, it is difficult to prove whether the contemporaneous onlooker has attributed to a pictorial element, which he could identify by form/shape, more than his personal contextual associations, e.g. a ritual knife being related to a ritual sacrifice, which does not constitute a symbol system, nor does it provide a noticeable epistemological surplus, as can be inferred from the most extensive, however finally futile seriation efforts of “Moche deities” by Lieske [79] and Golte [80]. Even if artisans relied on a conventional, standardized set of motifs, a “lexicon” or “tool-box” of scenes and pictorial elements as also compiled by Larco Hoyle [7] in the 1930s for numerous animal and plant motifs, “writing” needs a consensual code of combination of such elements, which for pre-Hispanic South America is not detectable.

Rather the archaeological record speaks against a structured arrangement of iconic signs or motifs, like in case of the arm and hand tattooing of a body found in a Pacatnamú grave showing a variety of animal and therianthrope beings ([3], Figures 36 & 36a). Indeed, the excavator on the first instance compared them with hieroglyphs and recognized, that they are very similar to pictorial elements found on Moche style pottery [3], but the drawing of the tattoo does not disclose any syntactic structure, nor does it tell a story. Rather the shapes of the beings may have been depicted on the skin as a kind of protection of the body as supposed for, though geographically totally unrelated, ethnographic parallels [37]. Similarly, typical publicly visible complex arrangements of iconic elements at the Peruvian coast like on the wooden statue in the religious-administrative center of Pachacamac close to present Lima nor on the shrine mural of the Huaca Cao Viejo pyramid in the Chicama valley, which was considered as a “ceremonial calendar” [81], disclose any obvious syntactical or other compositional structure between the alleged graffiti-like icons.

Rather the archaeological record speaks against a structured arrangement of iconic signs or motifs, like in case of the arm and hand tattooing of a body found in a Pacatnamú grave showing a variety of animal and therianthrope beings ([3], Figures 36 & 36a). Indeed, the excavator on the first instance compared them with hieroglyphs and recognized, that they are very similar to pictorial elements found on Moche style pottery [3], but the drawing of the tattoo does not disclose any syntactic structure, nor does it tell a story. Rather the shapes of the beings may have been depicted on the skin as a kind of protection of the body as supposed for, though geographically totally unrelated, ethnographic parallels [37]. Similarly, typical publicly visible complex arrangements of iconic elements at the Peruvian coast like on the wooden statue in the religious-administrative center of Pachacamac close to present Lima nor on the shrine mural of the Huaca Cao Viejo pyramid in the Chicama valley, which was considered as a “ceremonial calendar” [81], disclose any obvious syntactical or other compositional structure between the alleged graffiti-like icons. persuasion” [82]. Identification of the conventional meaning by iconographical analysis is only possible if the represented scene and its actors exhibit characteristic, unique morphological features which fit with the features of known themes. It is evident that what is referred to in art history as the iconographical method fully depends on the knowledge of a written or oral tale. Methodological reference to Panofsky for the interpretation of prehistoric iconic representations, e.g. of pre-Hispanic fine line paintings [79,80,83- 86] is therefore erroneous (cf. [39] for a critical compilation). As art historian Oskar Bätschmann pointed out it is always the text which provides the iconologist or the iconographer with the comfortable safety that “he got what was meant” [76].

Ethnographic analogy

Hence there is no direct answer to the professional question of the archaeologist or (art) historian “What did this act/ performance, participant or object meant to them?”, if prehistoric contexts are concerned or written documentation is otherwise missing. Meaning can only be attributed by empathy or intuition of the modern observer, which is a scientifically illegitimate approach. Ethnographic or ethnohistoric analogy [87,88], or the Direct Historical Approach [89,90] as a general method of inference is inadequate as well, since it is supposed to fail whenever variant formation and change through space and time has to be expected [91,92] As Boas [93] has argued, a generalization that the same ethnological phenomena are always due to the same causes is not tenable. The spatiotemporal continuation of form/shape and practice applied by a certain socio-cultural group may be archaeologically proved, but content (both physical and abstract) might have diverged in time or space. Form often continues, though content changes, and vice versa. Any legitimate extrapolation in time and space by inductive inference from a known dataset to unknown study objects, whether established for in-group or for out-group contexts, depends on the quasi homogeneity of cultural consciousness, intentionality, and practice of the respective practitioners, an assumption which in the majority of socio-cultural conditions cannot be taken for granted.

Therefore, in a strict epistemological sense the reconstruction of “meaning” of ancient art and artifacts with the objects as the sole source of information is impossible, and at least in nonliterate contexts the search for “authentic meaning” as a provable/ falsifiable result must end in agnosticism.

Inference theory

Both ethnographic analogy and any attempts of “preiconographic” description and identification of characters, implements, performances and the presumed intentions of its participants thus do not provide proof-like results, but sets of realistic probabilities in a continuum of cultural variant formation and resulting form/shape/content ambiguity. The methodological approach to deal with this ambiguity is inference theory, like IBE, Inference to the Best Explanation, a universal concept applicable to such diverse fields like archaeometry [94], philosophy [95], and theology [96]. Inductive inference is a matter of weighing evidence and judging likelihood, not of proof [97], and the evaluation of likely causalities, resulting in plausible hypotheses, gets as more profound, the larger the pool of potential explanations is [96].

Clear-cut inferences or conclusions from observed phenomena are only possible, if its correlation is monocausal, which is exceptional in culture studies. Rather any result may have multiple causes, motivations, driving forces and the like. This ambiguity, however, can be compiled and structured in a contingency matrix, typically consisting of four fields/quadrants and its multiples, respectively [35,98,99], like for instance the above Figure 3 for four culture domains or domains of the cultural consciousness. The contingency matrix as a heuristic tool provides a set of reasonable cause-effect, act-intention, form-function or shape-character variants, and the more encompassing the empirical ethnographic knowledge of the modern analyst, the more comprehensive the theoretically possible correlates will be covered by the matrix. The contingency matrix itself does not prejudice probabilities, but probability assessment is the next step by comparing each quadrant’s suggestions with the available archaeological context, ethnographic, historical, iconic, often only analogous information. Such plausibility assessments, which are open for revision as soon as additional data get available, finally result in well supported hypotheses, but proof-like statements will be exceptional.

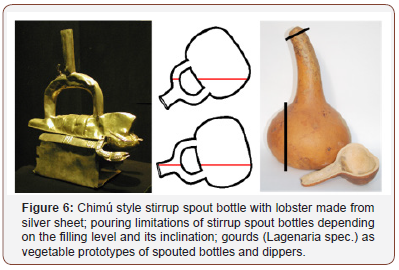

Form-Function Analysis of the Stirrup Spout Bottle

The suitability of an artifact does not predict its factual use function or the intentional acts of its contemporaneous maker/user, which the artifact was involved in. Summarized in a contingency matrix it provides the search frame, or frame of reference [100], for additional data supporting or excluding an individual suitability for its factual contemporary use. The careful plausibility check of all suitabilities of an artifact results in a hypothesis of its likely use function(s) for its ancient makers/users, whereas the mere statement of a single function, whether based on prima vista inference, intuitive reasoning, or analogy is a scientifically invalid speculation. Proof-like results are still the exception, and only its “unsuitabilities”, i.e. those potential functions which the artifact or type of artifact due to form or compositional constraints is unable to fulfill, can be taken for granted. There is a single published Cupisnique style stirrup spout bottle with perforations in the cylindrical body, which cannot serve as liquid container ([101], Figure 80), just a few bottles with an additional spout or hole in the body and base, respectively [102], and only few miniature stirrup spout bottles [103], thus pointing to a dominant, very persisting form of the vessel type through time. Similarly, the number of stirrup spout bottles composed of metal sheets is small, and whether they were initially tight, is unknown (Figure 6).

The stirrup spout bottle is prima vista a container, but with unknown content. Its stirrup shaped arch handle makes it convenient for handholding and carrying, but its fragile, mostly thin walled, low fired ceramic composition is inappropriate to carry it directly on the body, like for instance medieval stoneware pilgrim bottles for (sacred) water. Indeed, there is only a single published fine line painting, where a supposed woman carries a stirrup spout bottle on a shoulder sling ([18], Figures 1.17 and 4.50). It has repeatedly been remarked that the pouring behavior of the stirrup spout bottle is very restricted (Figure 6), releasing only small sips of liquid, and that they may have served for mere aesthetic decorative purposes only [104,105]. Filling of the vessels with potions also does not look trivial. As a powder container, due to lump formation, it would be almost inappropriate. Small, free flowing grains or kernels could be imagined as potential content, or a few small pebbles to use it as a rattle but have never been found in an archaeological context.

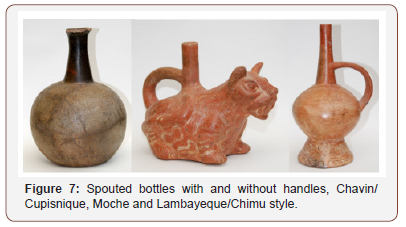

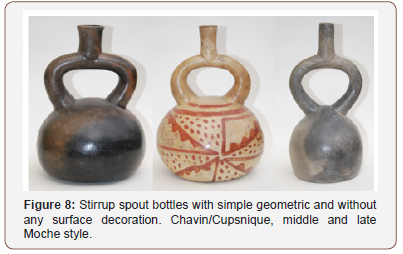

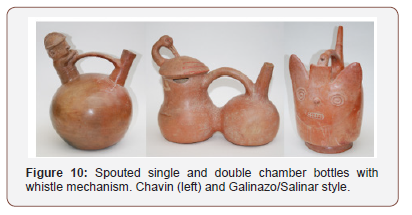

Finally, the stirrup spout bottle may have been a mere carrier or “canvas” for figurative-pictorial decoration, but there are also numerous undecorated specimens (Figure 8 and many other Cupisnique/Chavin style bottles with simple or no decoration, cf. [106]) which point to a practical function as a liquid container. Furthermore, the bottle type does not stand alone in its almost 3000 years of production time at the Peruvian north coast but is accompanied by similar single spouted bottles with and without handle (Figure 7), as well as various kinds of double spouted bottles with bridge handle (Figure 9). Among the bottles with bridge handle are numerous double chamber vessels with either a very simple, or a highly elaborated internal whistle mechanism (Figure 10, cf. [107]). Many of these whistle bottles not only produce a whistle sound, when blown through the spout, but also a very fine, bird-like sound, when water is poured out. These whistling bottles as well as the double-spout-and-bridge bottles, which often have very thin, tapering, easily breaking spout endings, suggest a more delicate container function than just for plain drinking water, whereby filling seems to be even more difficult than of vessel types with larger openings.

The Search for the Liquid Content

When considering more exotic liquids the historic and ethnographic information after the Spanish conquest of the South American Pacific coast can be taken as a generator of ideas [108- 112]. Chicha and fermented fruit juices, as an alternative to plain water, may have served as the liquid basis, and probably were not only brewed in workshops [113], but also on a household scale [114,115]. Meanwhile several scholars have considered the use of hallucinogenic plants and plant seeds, respectively, to have been used in a ritual context of pre-Hispanic societies at the Peruvian north coast up to Northern Chile [116-123], and even animal derived compounds like from the Spondylus oyster [124]. Chicha, the alcoholic corn beer, has been described by the chroniclers, but chicha has also been enhanced in its potency with intoxicating, hallucinogenic plant extracts. In Chapter 36 of his “Inca religion and customs” chronicler Father Bernabe Cobo referred to the diviners and how they summoned the devil. „For these consultations and conversations with the devil, they performed countless ceremonies and sacrifices. The most important one was to get drunk on chicha which had the juice of a certain plant called vilca added to it” [125]. Subsequently he mentioned the oracle or cult center of Pachacamac. Vilca is identified with the Legume tree Anadenanthera spec., the powdered seeds of which have also been snuffed, as mentioned above. Chewing of coca leaves with lime (alkali for cleaving the pro-drug in the saliva), which is still practiced at some places in the eastern slopes of the Andes, is clearly identifiable in Moche style vessel paintings, and coca leaves as well as supposed lime containers have frequently been found in archaeological contexts [126,127].

Concerning other highly active hallucinogenic potions there is ethnographic evidence from modern Peru about achuma [123,128], as well as ethnohistorical information by chronicler Anello Oliva [55]. The ethnographic record describes how short parts of the San Pedro cactus, Echinopsis [Trichocereus] pachanoi, were sliced like a loaf of bread, placed in a five-gallon can of water, and then boiled for seven hours. The completed brew is placed near the curandero’s (healer, shaman) other power objects, which as a group, are referred to as a mesa (“table”). From depictions of San Pedro-like candelabra cacti on pre-Hispanic stone carvings, pottery including stirrup spout and single spout bottles with handle Sharon & Donnan [128] concluded, that the magical-religious use of San Pedro can be documented over a span of more than 3000 years in the Andean area. Chronicler Anello Oliva has condemned the diabolic superstition of chieftains, who drink achuma potions, as the San Pedro drug is called in Quechua, for visions and divinations, which they get from the devil. However, there is no specific form/ shape information about the containers which have been used for keeping and administering the cactus juice in post-conquest times

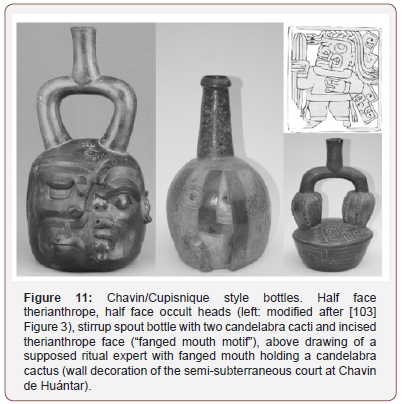

Figure 11 depicts a stone carving from the ceremonialadministrative center of Chavin de Huántar in the high Andes with a superhuman being, probably a ritual expert with the supernatural properties of his mythical predecessor - fanged mouth and snake headdress, and carrying a presumed San Pedro cactus in a procession-like manner. The cactus itself has also been modelled on pottery vessels, and Chavin/Cupisnique style stirrup spout bottles have frequently been decorated with fanged therianthrope beings and candelabra cacti (Figure 11, cf. [106]). Furthermore, two bottles are shown which suggest the representation of cult experts in a state of trance, or in the “jaguar-shaman transformation state”, as it was sometimes called, when therianthrope beings were depicted with feline morphological features [129]. Even if we conclude that the depicted cacti represent the San Pedro cactus we still cannot unambiguously infer from the decoration of the bottles to its liquid content, though the function of these bottles as containers for achuma or other hallucinogenic potions used in séances is at least not totally unrealistic. In the absence of residue analyses of psychoactive alkaloids in archaeologically recovered, uncleaned stirrup spout bottles, as has been succeeded in wooden snuff trays [42], even an occasional use as containers for drug storage and administration, respectively, stays hypothetical.

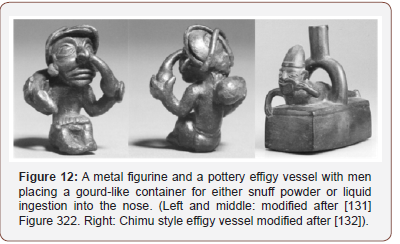

When using ethnographic and ethnohistoric analogy, supported by at least some archaeological evidence of hallucinogenic drug consumption in pre-Hispanic Peru (powder snuffing, coca chewing and nicotine consumption), we still do not know, how hallucinogenic (or other) potions may have been administered. Among the extremely rare examples of an administration scene is a small copper effigy with a person placing a gourd-like vessel into his nose. It is important to recognize that ethnographically both snuffing of powders and ingestion of liquids into the nose is documented, and the small gourd may have contained either a powder or a potion (Figure 12). The scene is important because it gives at least a hint how the thin tapering double spouted bottles may have been used: for pouring a thin, fine beam into the mouth (or anywhere else), or for nasal ingestion of a potion. A stirrup spout bottle with the same motif is also known. The person has been described as a “swimmer”, but it is much more likely, that he is practicing a séance. Interestingly both scenes with nasal positioning of gourd-like vessels do not exhibit any ritual-like aspects. The scenes may represent divinatory drug consumption in a very private atmosphere or perhaps even for profane psychedelic states [130].

Scenic Context Information

In its broadest sense context is not only the physical site where the artifact has been found but any spatial association with other material items, like physical content or content residues in vessels, but also use or wear traces of tools, objects, textiles and the like, which would confirm or support certain use functions. In the absence of archaeological records beyond funerary contexts and as deposits in selected architectural features, a limited set of figurative-pictorial representations of stirrup spout bottles with accompanying items is available, almost exclusively on Moche style pottery dating between ca. 400 and 700 CE. A large body of monographs on Moche style fine line drawings on stirrup spout bottles and floreros (“flowerpots”, kantharos-like bowls with flaring rim and fine line paintings) has accumulated over the last century attempting to identify and classify its subject matter, inter alia [18,133-136], and the work of Rafael Larco Hoyle on his museum collection. Only few of the many thousand vessels, however, depict pottery, and even less the stirrup spout bottle, which so far have not been studied explicitly with respect to its possible contextual use function.

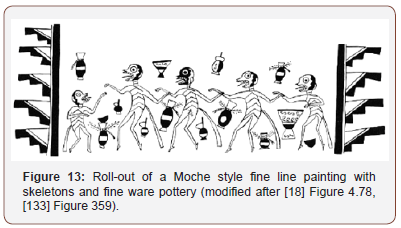

Several of these scenes depict skeletons in a dancing or feasting position and accompanied with typical Moche style fine ware pottery assemblages like spouted bottles with handle, stirrup spout bottles with base rim, large jars with ropes, as they are also depicted as transport charge on maritime reed boats, and floreros (Figure 13). Such scenes may exemplify the need of the deceased for feasting equipment, which he/she may have possessed during earthly life, and which was attached to the corpse as grave goods.

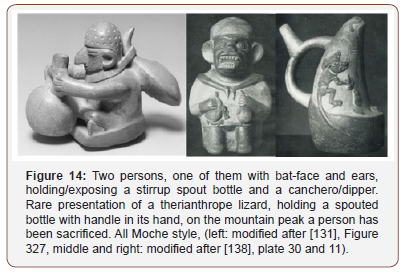

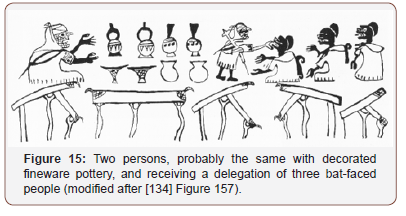

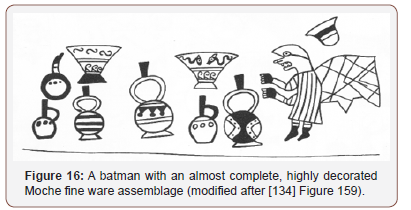

A few stirrup spout bottles in effigy form represent persons carrying or exposing a stirrup spout bottle and a so-called canchero, a pottery form resembling a large, half-cut gourd (Figures 6,14). The beings, repeatedly with bat features (Figures 15,16 with an almost complete set of fine ware vessels), have earlier been addressed as pottery dealers, which however is not very convincing. The canchero has previously also been called “corn roaster”, i.e. a kind of pan for roasting corn. However, many pieces of cancheros have outside fine line paintings, which contradicts its routine placement into the fire. Another possible use function is as a ladle or dipper, e.g. for filling drinking vessels with liquid from large storage or processing jars like for fermentation of smashed corn. The reason for the repeated joint presentation of the two vessel types, stirrup spout bottle and canchero, is not obvious, nor the role of the batman. Perhaps the bat was just one of the powerful animal genera in Andean cosmology like the felines [137] and potting at some time may regionally have been related to the skills of a bat-faced professional predecessor.

A stirrup spout vessel with a figurative batman carrying two large open mouth jars on his shoulder is decorated with a fine line scene of a similar pottery assemblage in front of a seated person (Figure 15). A second person which may be the same in a different situation receives three visitors with bat faces. The lower floor of the scene is made up of five wooden huts or shrines. The bat-faced persons point to a ritual happening like a séance, divination or healing performance where a group of clients has visited a ritual expert with his paraphernalia in front of him, as described for the mesa in Sharon & Donnan’s [128] ethnographic report. The left part of the scene has also been interpreted as a potter’s workshop exhibiting his produce for sale, which again is not very convincing.

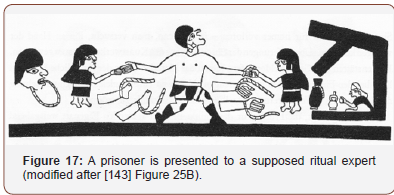

Huts or simple shrines are a frequent component of scenes with processions or individuals and groups of prisoners brought to an authority sitting/residing under its roof. The person in the shrine is sometimes accompanied by pottery vessels including a stirrup spout bottle. In the fine line painting of Figure 17 in addition to the prisoner a decapitated head as well as arms and legs are depicted, probably referring to a (ritual) sacrifice, which the captive will suffer soon. The large jar with rope in front of the person sitting under the roof of the shrine has been considered as a container for human blood or chicha, but without proof. Indeed, the supposed sacrifice of the prisoner may be part of a formalized ritual, with the pottery being paraphernalia which the authority or ritual expert needs for a proper performance. Whether sacrifice and decapitation scenes are always actual happenings or mere representations of mythical deeds, is unknown, but both at the Peruvian north and south coast caches with trophy heads and disembodied limbs, respectively, have been found [139-141], and pre-Hispanic mountain sacrifices are found throughout the High Andes from Peru to Chile and Argentina. Sacrifices in mountain landscapes are frequent motifs of effigy vessels [142], and on a bottle shaped in the form of five mountain peaks with a sacrificed victim on top of the highest peak, like Figure 14 (right), five stirrup spout bottles are depicted ([83], Figure 182), supporting the notion of spouted bottles as paraphernalia in human (and animal) sacrifices.

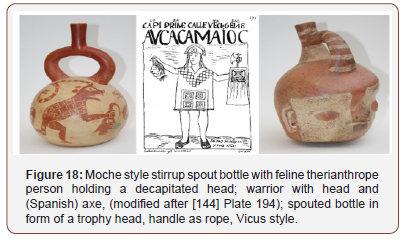

Therianthrope beings holding or exposing a knife (tumi) and a decapitated head, or “trophy head” when already fixed at a rope, are frequent themes of effigy bottles and fine line paintings (Figure 18). Following chronicler Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala [144] warriors among former Inca tributaries still by the end of the 16th century practiced the same pose (since it is unlikely that Poma de Ayala had an archaeological effigy as prototype for his drawing). Both in the far north (Vicus style) and in the south of present Peru (Nazca style) vessels with trophy head design have been produced.

The crown of a rare copper staff or scepter (Figure 19), similar to the staff carried in a procession scene depicted by Kutscher ([134], Figure 153), and to the scepter crowned by a shrine with courtyard from the elite tombs of Sipán [145] depicts a two-storied shrine. In the upper store, which is reached by a ladder, a person, probably a ritual expert, sacrifices a deer-like animal. At the backwall of the basement of the shrine three vessels are placed on a wallboard, a rimmed pot flanked by two double-spout-and-bridge bottles. The assemblage may be taken as a confirmation that the depicture of pottery items in huts and shrines is not just an aesthetic decorative element but is related to the acts and activities performed in these architectural structures.

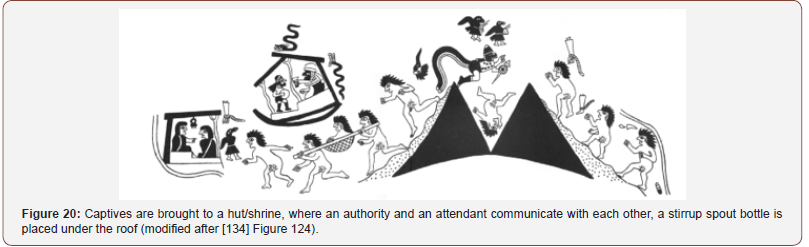

In a further scene with naked captives (Figure 20), one of them is thrown into a mountain gorge, another, probably the chieftain of the defeated opponents, is carried in a litter towards a hut, where two ordinarily dressed persons are in communication, one of them sitting on an elevated pedestal with a stirrup spout bottle placed under the roof. Bird-faced helpers and a fox or feline faced warrior with large tail are accompanying the scene. In a second hut, also resembling an audience-like situation, an elaborately dressed person seems to welcome a visitor offering him a large beaker or small florero.

The nature of these bellicose scenes, whether actual territorial wars or ritual/ceremonial encounters for reenacting and stabilizing the cosmic and the social order, is unknown (cf. [178]). Though the depicted scenes with prisoners brought and presented to an authority as part of a subsequent (ritual) sacrifice, look small in scale of the performance, they may just resemble the primordial prototype, or a “cut-out” with the most important ritual element of what has also been performed on a much larger scale with numerous participants on both sides, spectators as well as victims. The pyramidal ceremonial-administrative centers at the Peruvian north coast, Huacas, provided plenty of public space in courtyards, with shrine-like structures at one of the court walls, where the political, and probably often in personal union religiouscosmological leader may have resided during the spectacle [146]. The polychrome murals, “running” wall paintings, of the courtyard of Huaca Cao Viejo in the Chicama valley, for example, represent a “chain” of naked prisoners and a therianthrope “decapitator” being with an axe (tumi) [147], which may have been the “executive” ritual expert or its mythical prototype, similar to the representations on many effigy vessels. Both victims as well as attendants/spectators of these highly visible large assemblies may thus have already been tuned by the mural decorations on what will follow, the wall paintings thus not only providing the public space with sacredness, but also being “program”, both colloquially as well as on a metalevel description of this frequent architectural feature [148].

Whereas the same theme on murals was visible to a larger audience and the public, respectively ([149] Figures 6&7 for typical fine line painting scenes on murals), the pottery items itself and the subject matter of the fine line paintings were only recognizable for small distance onlookers like the owner/user and his/her peers in rituals, ceremonies, receptions, and reunions. Thus, if authorities supervising a fine line pottery workshop have intended to decorate stirrup spout bottles with ideologically laden themes and use them as vehicles for political propaganda, its outreach in terms of the number of affected people must have been quite limited.

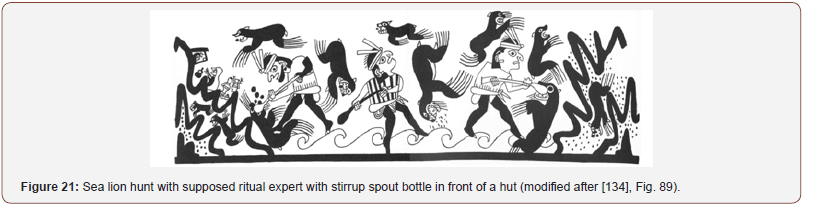

In Figure 21 a sea lion hunt is depicted. The dressed hunters seem to fight face by face with the animals which probably was rather dangerous. On both edges of the scene already killed animals have been deposited on the shore. On the left side, also on the beach, a person, probably a woman, has a stirrup spout bottle in front of herself and two large jars and further equipment in the back. Whether the small structure she is oriented to, is a shrine or hut is difficult to decide. In very similar scenes, but without a depicted stirrup spout bottle, the hut is well identifiable with a person sitting under the roof ([134], Figure 88, [150], Figure 305b). The scene may represent a divination ritual where the cult expert, facilitated by the consumption of a psychoactive potion, communicates with a superhuman being, e.g. the mythical master of the sea lion population, to ask for permission as the prerequisite of a safe and successful hunting outcome. Based on ethnographic analogy it is said that the bullets in front of the mouth of the sea lions are pebbles which the animals have swallowed, and which may have been considered as sacred, and ritually collected ([150], [151], Figure 212).

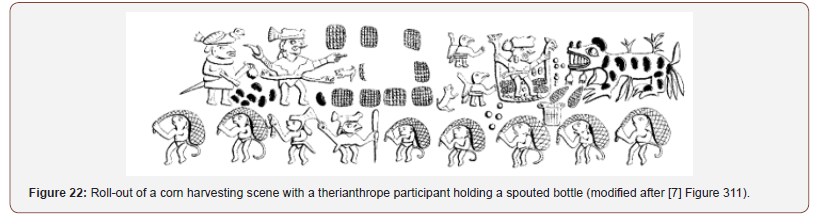

Probably related to ritual crop procurement activities a relief scene on a late Moche style spouted bottle with handle represents a mythical corn harvest or its reenactment (Figure 22). A supposed supervisor with condor headdress carries a similar spouted bottle in his left hand. Two additional therianthrope persons with fanged mouth (Larco Hoyle’s Ai Apaec) and snake belts are depicted, the left one holding a gourd or gourd-like vessel, but without identifiable use function. The fanged mouth being on the right side of the roll out stands on a double-headed snake-like animal and keeps its both heads with stretched arms in his hands. Such presentation poses where the human or superhuman agent keeps two snake heads, two felines or two corn stalks with cobs in both hands are a frequent motif on late Moche and early Chimu relief bottles [59]. Without overstressing the inference from the figurative representation, the right being surrounded by the double headed snake may very well have been considered as the mythical predecessor, and the left, less attributed one as its actual representative, enacting or reenacting the harvest ritual.

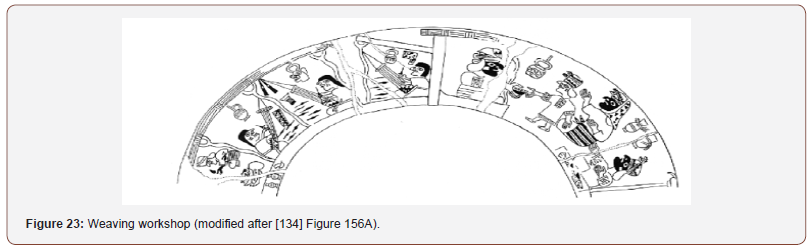

The next scene is referred to as the pictorial representation of a weaving workshop (Figure 23). It is more than a mere repeat of the same element, but a larger architectural complex with a kind of reception place with a well-dressed authority welcoming a delegation of similarly elaborately dressed persons. The (female) weavers work in roofed huts or courts, and each of them is accompanied by spouted and stirrup spout bottles, respectively. All bottles are decorated and positioned close to the roof, perhaps on wallboards which have not been depicted for technical reasons. Weaving may have been a sacred activity, but it is difficult to comprehend, what role the pottery may have played in this artisan working context. Rather it seems that the whole workforce of the workshop belonged to a social group which had access to nicely decorated spouted bottles, and these items were their personal belongings, indicating that they both worked and lived in this building.

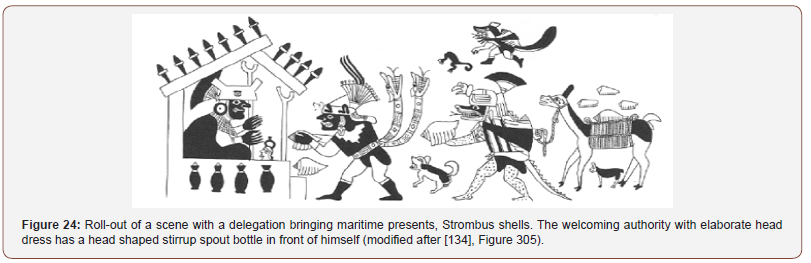

A further audience-like scene shows a chieftain or ruler receiving a delegation of elaborately dressed visitors, one of them with animal face (Figure 24). A llama was brought for transportation of Strombus shells, probably used as highly esteemed, sacred trumpets in rituals and ceremonies. In front of the authority which resides in a shrine which is decorated with war clubs (porras), a stirrup spout bottle modelled as a human head is positioned, probably his personal (sacred) item. Traces of abrasion at the bottom of stirrup spout bottles compatible with this positioning have been studied by Mogrovejo Rosales [17].

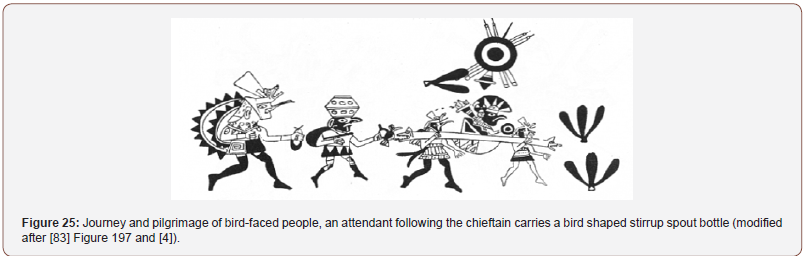

Next a presumed journey or pilgrimage scene is shown, where the chieftain or head of the group is carried by two attendants in a litter (Figure 25). All five human beings have bird heads and thus may be understood as birdmen or bird warriors. From the fine line painting it cannot be inferred whether the scene represents a mythical procession in the past, its ritual reenactment, or the actual journey of bird people to attend a meeting, ceremony, or a ritual battle (above the chieftain a war club with spears is positioned), where the artisan has depicted the beings as they are, whereas the actual travelers had to wear bird masks and dress elements. Most impressive is the attendant following the litter, who carries a stirrup spout bottle modelled as a bird figurine. The bottle must have been extremely valuable, and of course quite fragile, justifying an individual carrier following immediately behind the chieftain of the birdmen group.

In 16th century Quechua the term huaca/guaca signified sacred/holy/admirable items [152], which the chroniclers have often translated as idol with its pejorative connotation of devil’s work [144]. At the time of the conquest each Inca house pertained of a guaca for talking with the devil [153]. The huaca term was also used as term for mountain sanctuaries and for the monumental architecture and its remains, the partially eroded adobe pyramids in the coastal dessert valleys. The context of the figurative stirrup spout bottle in the birdmen scene is fully compatible with a huaca, idol or “fetish”, which has high spiritual value for its owner, though we have no proof for its primary function as a supposed liquid container.

How the bird-faced chieftain has used his stirrup spout bottle is not disclosed in the pictorial. Keeping the long duration of the vessel type in mind, its sole use as an idol/figurine is unlikely, since the complicated, mold formed bottle [107,154] would then probably have been replaced by technically more simple figurines without spout and container function. For sure, contemporary (small distance) observers may have drawn conclusions from the elaborate artifact on its owner. The chieftain may have been a ritual expert himself or may have used his idol in private séances for contacting his professional master or a genealogical ancestor in a state of drug induced trance. As a birdman he may have placed his idol, the bird shaped stirrup spout bottle, which may well have been animated and powerful, in front of himself in his hut or shrine, and got in contact with his counterpart in an Alter Ego like identification mode [155]. However, this and similar hypotheses, as plausible they may be, lack confirmation by chemical content analysis of at least a few well conserved spouted bottles from an undisturbed archaeological context. The semiarid climate at the Peruvian north coast is predestined for conservation of even chemically fragile heterocyclic secondary metabolites derived from hallucinogenic plants.

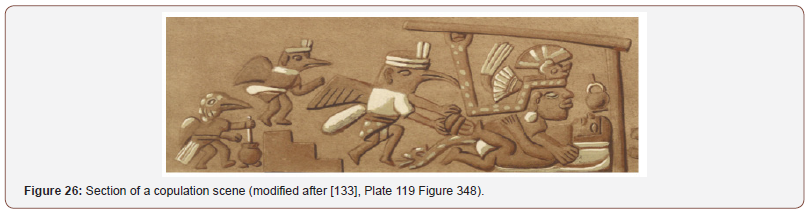

It is often impossible or at least extremely speculative to describe both the concrete themes as well as to infer the intentions or the mythical background of many of these scenes, which is one of the reasons why archaeologists and anthropologists are so reluctant to earlier pre-Hispanic art descriptions by art historians. As a risk of misunderstanding reference is made to the re-evaluation of socalled erotic scenes on pre-Hispanic pottery as part of gender and diversity studies [156-158]. Obviously scholars want to infer sexual practices and diversity from scenes where already the primary subject matter is difficult to be identified, roll-out drawings may be imprecise, and where hints on superhuman qualities of the actors make it highly uncertain, whether the scenes were representations of mythical deeds of ancestors, of its ritual reenactment, or of actual sexual practices of elites and commoners at the time of artifact making. Figure 26 shows such a sexual intercourse scene depicted on Moche style pottery (cf. [59], Figure 4, [159], Figure 3.10).

The roll-out has been selected, since in this quite standardized scene, which supports a persisting mythical theme, under the roof of the shrine a stirrup spout bottle is placed. Moreover, on the left part of the relief a bird-person/servant is obviously preparing something in a pot, perhaps a liquid extract as has been suggested by Chapdelain ([160], Figure 12) for a very similar, but not identical roll-out of a jar found in a tomb near plaza I of Huaca de la Luna in the Moche valley. Another bird-faced attendant is placing an object, which cannot be precisely identified in any of the published roll-outs and probably is not a stirrup spout bottle, on the back of the male participant. Provided that the object is a liquid container, (sacred) potions may also have been administered for supporting fertility in acts of (ritual) copulation.

Summary and Conclusion

If a broad ritual term is applied, embracing both religious and non-religious proscribed or otherwise standardized acts and performances, the stirrup spout bottle is without doubt a ritual implement, because it has been encountered as a frequent grave offering at the Peruvian north coast over a period of almost 3000 years, and funerals are typically considered as solemn performances followed by the mourners in a certain rite or procedure, one of a few universalities in culture studies. However, the ritual term then would neither specify, why this special vessel type has been developed, why it got used as a funerary gift, nor what role and position it played in the daily life of people, since stirrup spout bottle fragments were also found in special architectural as well as domestic contexts.

Obviously, there is a discrepancy between the enormous number of Moche style stirrup spout bottles, which have been produced and recovered (including the looted ones without archaeological context) and its rare representation on effigy bottles and in fine line drawings. The plain bottles and its content were probably considered as indispensable tools and vehicles to achieve a certain task, rather than as a central object of desire on its own. The limited scenic context can be divided into three basic cases

• A few effigy bottles and drawings present characters carrying or exposing a stirrup spout bottle together with a canchero/dipper or being accompanied by a whole assemblage of fine ware pottery, which earlier stimulated its identification with pottery sellers or workshops.

• A similarly low number of representations shows travelers or pilgrims carrying their vessel in a huaca/idol-like fashion, as if they cannot miss it when being abroad or joining a reunion with others.

• The predominant pictorial and probably physical correlation as well, however, is “stirrup spout bottle and hut/ house/roofed court/shrine”, i.e. architectural structures for living, working, and various ritual or ceremonial performances like receiving visitors, clients or captives.

This points more to a practical use than to social signaling, because inside the house or under the roof of the hut visibility is restricted. Similarly keeping double-spout-and-bridge bottles on a wallboard beneath the roof looks more like a safe storage of the implements when not in use, rather than as an ostentatious presentation of artefacts for its aesthetic or prestigious value. Since quite unspectacular spouted bottles have also been found, the social signaling effect is probably secondary and depends on the quality and thematic subject matter of the effigies. Most probably the aspect of social representation of even decorated pottery is generally overestimated in archaeological and art historian artefact analysis due to its relative predominance in the find contexts. The practical use and application of the stirrup spout bottles in the depicted architectural structures may have addressed both the profane and the sacred realm, but a mundane utilitarian purpose for using this complicated, not at all practical vessel form which nevertheless persisted for almost 3000 years, is not at all evident.

Culture, art and agency theories point to the intentional doing the unknown artifact must have been part of in ancient human activities. Form-function analysis narrows the range of use functions, but only content analysis and use-wear traces can specify factual uses, which are still missing. Comparative religious studies suggest that the numerous therianthrope beings depicted on pre- Hispanic artifacts in the Andes, are not just an outlet of excessive aesthetic creativity, but represent superhuman entities, and thus point to religious-cosmological tasks of the human agents in a broader sense, which the bottles may have been involved in. The religious-cosmological sphere including interaction with ancestors, divinations, fertility procurements, and ritual sacrifices may thus have been the primary task of application rather than the sociopolitical, the economic, or the aesthetic domains.

The spouted bottles, difficult to fill, and releasing its content only in small doses, may have at least occasionally, but perhaps even predominantly been used as liquid container for “special potions” including hallucinogenic brews of various potency, which were used by ritual specialists for all kinds of divinations, but most probably also by commoners for contacting superhuman beings, ancestors and predecessors, in states of trance. When appropriately shaped or decorated the bottles may have provided its owners the opportunity to be simultaneously used as personal huacas/idols, and on top exhibited a certain social signaling effect when visible to others, indicating both social status and spiritual power, e.g. interacting in reverence with mighty animal guised spirits. An extension of this still weak hypothetical result as a kind of “archaeological analogy” to other time periods and geographic regions in the almost 3000 years of occurrence of the stirrup spout bottle, beyond the “Moche” time span would fall under the same restrictions like the unconditioned application of ethnographic analogy: form may have survived, but content and use may have changed. However, the repeated representation of candelabra cacti and superhuman beings with “fanged mouth” on Chavin/ Cupisnique style spouted vessels and architectural sculptures strongly supports this proposal for the early period of pottery making in Peru as well.

Keeping in mind the phenomenon of infinite variant formation in human cultural interactions and the ambiguity, which results from multicausal correlations between human intention and physical-material output, managing this ambiguity is probably the biggest challenge in the functional analysis and description of (pre)historic artifacts. Besides various anthropological theories, ethnohistorical and ethnographic analogies can supply “cases”, which have effectively been realized by real people in real situations, but theoretical reasoning about undocumented possible causes and reasons is also valuable for filling the contingency matrices. Careful comparison of the numerous resulting contingencies with the material items and the archaeological record may then lead to a ranking of reasonable probabilities, resulting in well-founded hypotheses, but seldom in proof-like conclusions.

Some typical inferential pitfalls need to be mentioned. When figurative-pictorial scenes are used as major context information, there is a risk of “cherry picking”. The scholar may focus on those scenes which fit to what he/she wants to prove. Indeed, there are numerous other scenes particularly on Moche style pottery, which lack any context information concerning supposed ritual paraphernalia, but depict obvious ceremonial, socio-political performances, healing scenes without any religious-cosmological hints, as well as plant, animal and geometric motifs, which the modern out-group observer would qualify as mere aestheticdecorative design elements. Concerning the thematic shaping and surface modification of pottery vessels and of the stirrup spout bottle in particular, the question thus arises “What did that mean to them?”, or in an anthropologically more accurate language, what was the motivation/intention of the potters and their sponsors/ commissioners/clients, to make and get access to vessels with such designs. The answers may reach from “direct labelling of usefunction” via “supportive motifs for use” to “aesthetically appealing designs, which did not distract from intended use”.

When ethnographic analogy is used for the hypothetical classification of artifacts, the classified artifact type may afterwards be used for proving a certain cultural phenomenon exhibited by the agents responsible for the archaeological record, which, however, bears the risk of circularity. In the special case of ethnographic and ethnohistorical information supporting ritual drug consumption in pre-Hispanic South America, the supposed ritual paraphernalia itself are no proof of drug consumption at its find location. Rather drug consumption would only be proven by chemical drug identification in such containers, and ultimately by forensic drug identification in human tissue remains, as has already been proven for coca and tobacco/nicotine consumption [161-163] as well as ayahuasca-type alkaloids [164].

Another traditional pitfall is inference of meta-level information from the presence of an artifact class, without prior proof of its indexicality for the cultural or socio-political information in question. Reference is made to the inference of political organization from style. Since the early days of Pre-Columbian archaeology and art analysis around 1900 [165,166] stylistic features of decorated pottery have been used for defining “cultures” and ethnicities and inferring its alleged territorial expansion and political influence. This erroneous notion ultimately goes back to the short, but very persistent diffusionist “Kulturkreislehre” of the Frankfurt school of Leo Fresenius [167,168], in concert with the admiration of the concept of nation building in European historical studies in the 19th century. In particular, “Moche style” pottery in its various stylistic facets, all under the notion of a “Moche culture” [7], has been used to establish the idea of a Moche civilization, society, state, kingdom, and almost empire, and to pinpoint its territorial expansion from its first archaeological encounter in the Moche river valley near Trujillo through time.