Research Article

Research Article

Early Evidence for Alcohol Consumption in Iron Age Messapia (Southern Italy) through Organic Residue Analysis, Use-Alteration Traces and Vessel Morphology

Florinda Notarstefano1,2*, Serena Perrone2, Francesco Messa2, Grazia Semeraro1

1Dipartimento di Beni Culturali, Università del Salento, Italy

2Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie Biologiche ed Ambientali (Di.S.Te.B.A.), Università del Salento, Italy

Florinda Notarstefano, Dipartimento di Beni Culturali, Università del Salento, Via Dalmazio Birago 64, 73100, Lecce, Italy.

Received Date:May 01, 2023; Published Date:July 08, 2024

Abstract

The paper presents the results of an interdisciplinary investigation aimed at clarifying the function of local matt-painted pottery through organic residue analyses of vessels recovered from two Iron Age sites in southern Italy, Castello di Alceste and Castelluccio (Brindisi). Both sites are part of the Iapygian culture of the Salento peninsula, where since the 8th century B.C. the native populations were engaged in processes of settlement expansion, socio-economic differentiation and elite proliferation, including commercial relationship and cultural transmission with the Greek world, as evidenced by the presence of imported vessels.

The major role played by ceremonial practices that possibly could have involved alcoholic beverages, particularly in feasting contexts, is suggested by the rich corpus of local matt-painted ceramics and the reoccurring set of drinking vessels in many Iron Age settlements. The specific content of these vessels has never been investigated by organic residue analyses although the morphology of some pottery shapes and the use alteration traces on their interior walls show comparisons with those observed in ceramic vessels used for alcohol fermentation reported in many ethnoarchaeological studies. Organic residues analysis was carried out by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) on 21 samples allowing the identification of Pinaceae products (resin/pitch), beeswax, plant waxes together with fermentation biomarkers. Based on integrated studies, we suggest that the vessels were used for the preparation and/or consumption of cereal- or other plant-based fermented beverages. These preliminary results give the earliest direct evidence of the actual use of local matt-painted vessels and represent a starting point for a large-scale investigation of local pottery assemblages by organic residue analysis, in order to better understand ceremonial practices within the social development of the native communities of southern Italy during the Iron Age.

Keywords:Iron Age, Organic residue analysis, Pottery, Fermented beverages, Feasting, Iapygian culture, Messapia

Introduction

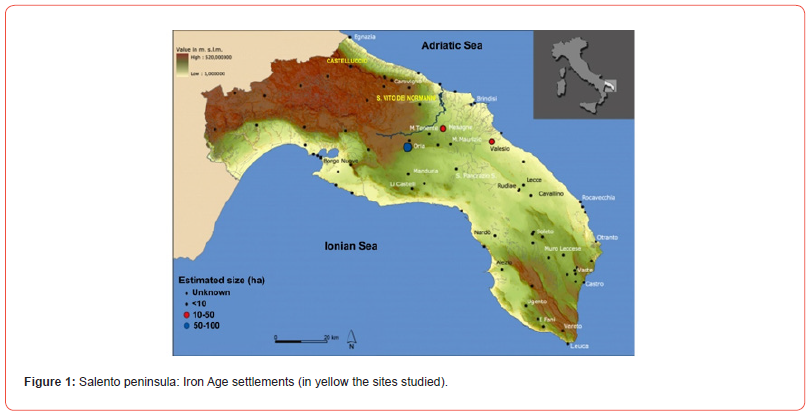

Over the course of the first millennium, the geographical location of Messapia (Figure 1), between the Ionian and Adriatic seas, enabled the development of constant relations within the framework of Mediterranean mobility. During the Iron Age, the Salento peninsula was at the center of traffic and migrations that led to the foundation of the Greek town of Taranto in the late 8th century BC. This period also witnessed the development of the Messapian population in southern Puglia, with different traits than the Daunians in the north and the Peucetians in the center of the region.

The archaeological investigations carried out in the Iron Age settlements of the Salento peninsula evidenced processes of settlement expansion, socio-economic differentiation and elite proliferation among the native populations between the 8th and the 6th century BC, including commercial relationship and cultural transmission with the Greek world, also confirmed by the presence of imported vessels [1-3]. This period witnessed in fact a growing mobility within the region and the emergence of new settlements. The native communities were kinship based and developed greater social and political complexity over time, especially as a consequence of the interaction with the Greeks. Culture contact was a major factor in local socio-economic development and recent studies have focused on the complexity of this interaction and on the active role played by the natives in their own cultural and social development, emphasizing also the emergence of ceremonial and feasting practices [4-6]. Evidence of commensal practices that could have involved the consumption of alcoholic beverages is suggested by the rich corpus of local matt-painted pottery and the reoccurring set of drinking vessels (bowls, jugs, askoi, globular and long-necked jars) in the ritual contexts identified in the settlements of Roca [7-8] and Vaste [9-10], where local ceramics are associated with numerous Greek vessels for wine consumption. In these contexts, the distribution and consumption of food and alcoholic beverages probably helped to shape and enforce social and ideological cohesion among people from different settlements. In many past societies, the consumption of food and alcoholic beverages was in fact a fundamental part of everyday life as well as integral to ritual and feasting events. Therefore, alcohol drinking was likely associated with cultural and economic changes, and played an integrative role in constructing communities’ identity, political power and maintaining social cohesion [11-13].

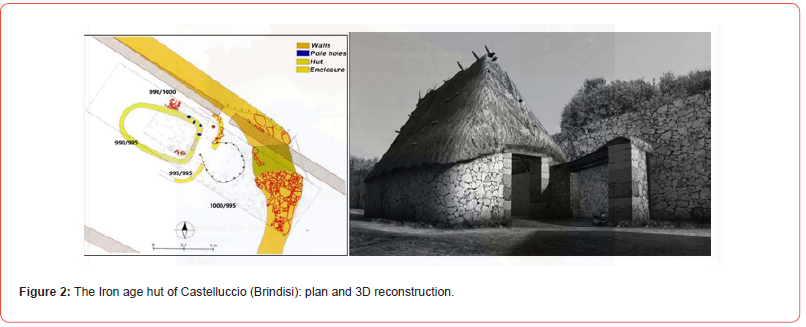

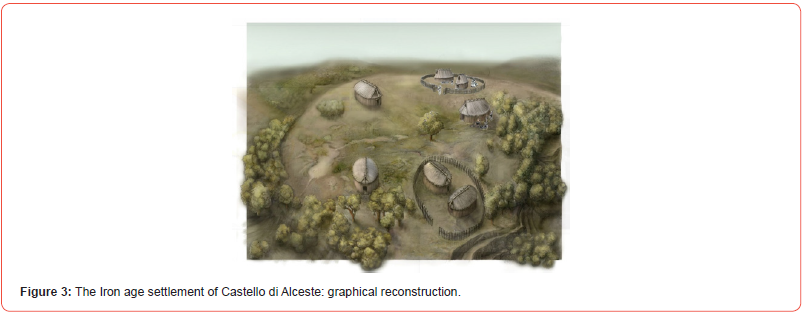

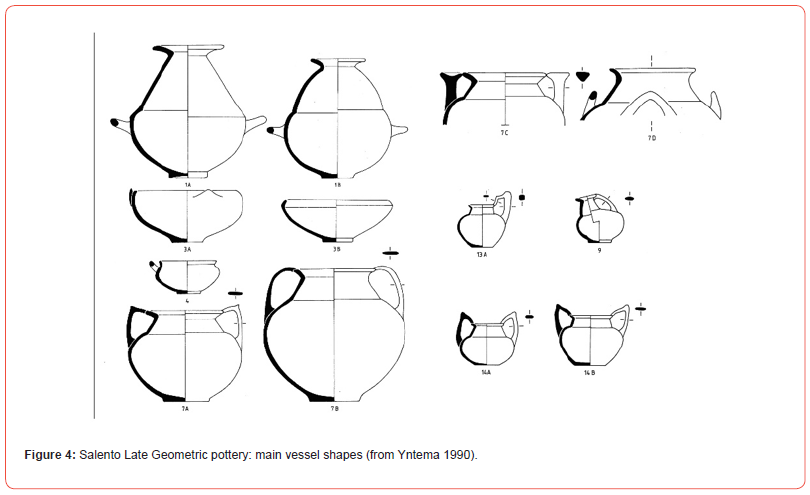

This study focuses on two key sites of the Late Iron Age of southern Puglia, Castello di Alceste (S. Vito dei Normanni) and Castelluccio (BR). Both these sites belong to the series of new settlements founded during the 8th century B.C., located on the top of heights and surrounded by enclosure walls. These settlements were characterised by oval or apsidal dwellings delimited by low walls and arranged by kinship related clusters (Figures 2-3). Greek imported ceramics also arrived in these small villages not far from the Adriatic coast, suggesting an interaction with coastal communities and, through them, with overseas trade. The Greek imports are found together with storage vessels, coarse ware containers and hundreds of fragments of local matt-painted ceramics. The geometric decorative patterns on this handmade local pottery class (Salento Late Geometric, Figure 4) reflect local traditions but new ornaments inspired by Greek ceramics appear on the vessels in the later 8th century, also because of the increase of the imports of Corinthian and West Greek wares [14]. Low forms (bowls and beakers) can be associated with drinking and serving vessels, while high forms (jars) can be associated with serving, food and drink preparation, transport and storage. Based on their typological characteristics and the presence of use alteration traces, such pottery types are commonly regarded as alcohol-related vessels, but there is a lack of scientific analysis to understand their functions. The jars have narrow necks and globular bodies, similar to ethno-archaeological flask/jug form, a vessel type known for alcohol production [15]. The internal walls often show the presence of pitting and corrosion, particularly in the upper part. According to experimental and ethnoarchaeological studies, the chemical attack of the ceramic paste by the acidic components of fermented beverages causes characteristic alterations in the form of superficial cracks and detachment of the ceramic surfaces [16]. These alterations are clearly observable as they leave irregular depressions or circular pits on the interior walls of the ceramic containers [17].

Our aim was to investigate the content of local matt-painted pottery in order to verify a possible use related to the production and consumption of fermented beverages. To test the hypothesis, organic residue analyses by GC-MS were carried out on 21 pots showing the presence of use alteration traces.

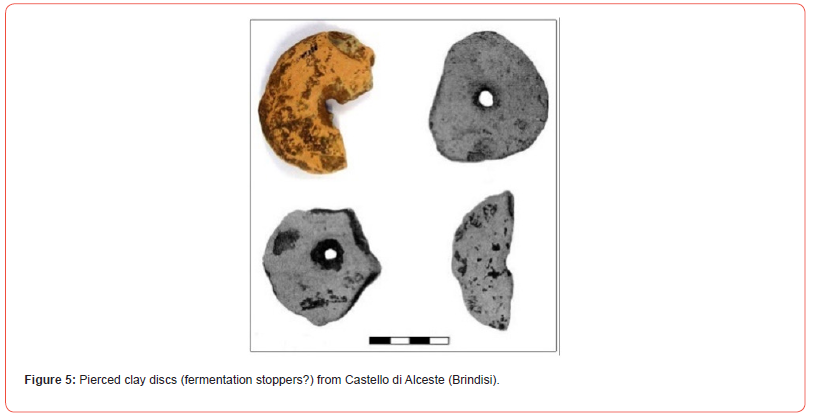

The samples from Castello di Alceste come from different contexts of the Iron Age settlement where the rich concentrations of matt-painted and coarse ware vessels indicated domestic/craft activities. In these contexts some pierced clay discs (Figure 5) were found, similar to the fermentation stoppers - a system that allows gasses given off by fermenting beverages to escape - documented in the ancient Near East [18].

The samples from Castelluccio were recovered in the levels of the apsidal Iron Age hut brought to light near the enclosure wall. The ceramic assemblage found there was particularly rich in local matt-painted pottery and big storage vessels, probably placed in a small enclosure outside the hut. Stratigraphic and archaeobotanical analyses allowed recognising considerable amounts of legumes and cereals, providing important information on the agricultural exploitation of the territory in this period. In the same context, which reflects a high social level of the householder, a precious Greek geometric jug with traces of an ancient restoration made with an organic pitch was also found [19].

Materials and Methods

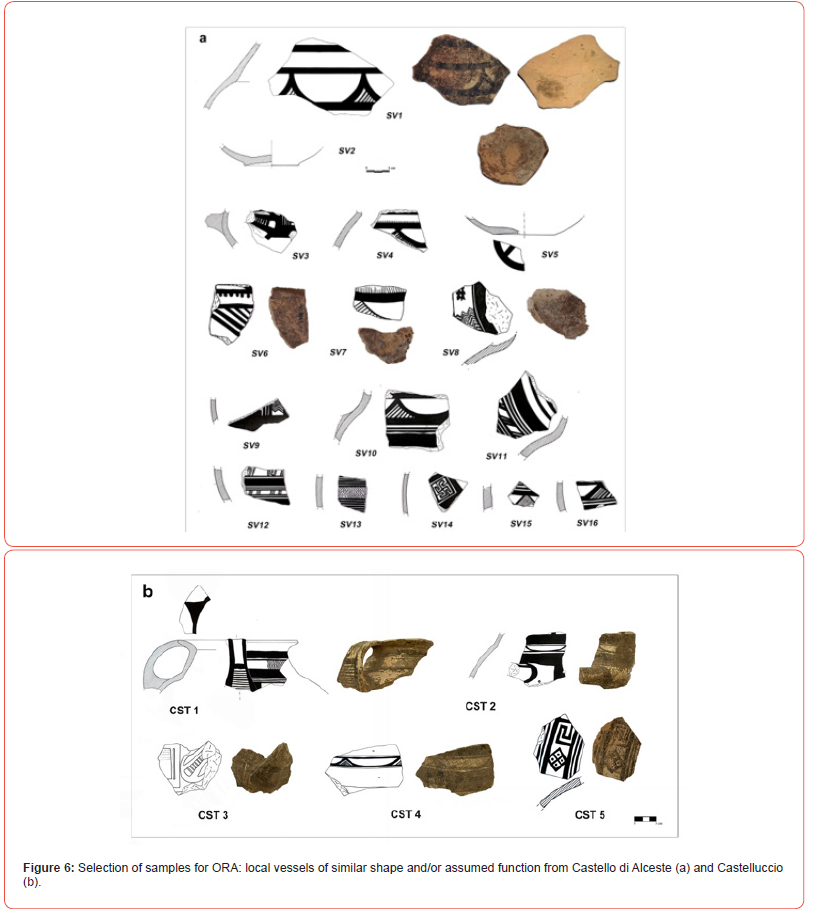

Twenty-one ceramic fragments were analysed by gas chromatography mass spectrometry: 16 samples came from Castello di Alceste (Figure 6a) and 5 from Castelluccio (Figure 6b). The selection of archaeological samples took into consideration the archaeological and stratigraphic context, the overall vessel shape and the presence of use-alteration traces.

For this preliminary study, we selected only high forms (globular and long-necked jars) associated with serving, food and drink preparation by traditional typological studies. The long-necked jugs are distinctive by wide out turned rims, tall conical necks, low rounded bodies, with two horizontally attached tube shaped handles. The globular jars have out turned rims, short conical necks and two vertical band handles from rim to shoulder. All the vessels have flat bases and matt-painted geometric decorations on their external surfaces. The geometric ornaments usually cover the vessels from top to bottom, in particular on neck and shoulder. We also sampled small sherds pertaining to undetermined vessel shapes characterized by the presence of thick signs of pitting and corrosion on their interior walls. External surfaces or soil samples from the burial contexts were sampled to control for exogenous contamination.

Potsherds were pulverised and 0.5 ml of a standard solution of nonadecane (1 mg/ml), required for the quantification of lipid extract, was added to the powdered sherd samples. Charred surface residues were removed using a sterile scalpel and powdered. Extractions then proceeded as for the powdered sherds.

Lipid extraction of powdered sherds (1-2 g) was performed

following two different protocols: extraction with chloroform:

methanol (a) to obtain a total lipid extract [20] and alkaline

extraction (b) to identify short-chain carboxylic compounds which

can be present in high quantities in fruit products [21].

a) The so-called total lipid extract (TLE) of each sample

was obtained by adding a chloroform/methanol mixture (2:1

v/v, 5 mL). Extraction was performed twice by ultrasonication

(30 min at 40° C). After centrifugation, half of the TLE was

evaporated under a gentle stream of nitrogen and hydrolysed

by adding 5 ml of NaOH/MeOH+H2O (9:1) and heating at 70° C

for 1 hour in ultrasonic bath. The liquid fraction was acidified

with HCl (1 M) and extracted twice with chloroform (5 ml). The

solvent was then evaporated under a gentle stream of nitrogen.

b) 1 g of the powdered sample was extracted with 4 mL of

KOH (1M) in distilled water by ultrasonication at 70° C for 90

min. After centrifugation, the liquid fraction was acidified and

extracted twice with ethyl acetate (3 ml). The extract was then

evaporated using a gentle stream of nitrogen.

All the extracts were derivatized with 50 μl of N,Obis( timethylsilyl)tetrafluroacetamide (BSTFA, Sigma) at 70° C for 30 min and analysed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

The GC-MS analysis were carried out at the Laboratory of Synthetic Organic Chemistry of the University of Salento, in the Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences and Technologies, using an Agilent Technologies 6850 II series gas chromatograph with a fused silica capillary column (5% phenylpolymethylsiloxane, 30 m, internal diameter 0.25 mm x 0.25 μm film thickness) with a split/splitless injection system operating in the splitless mode and maintained at 300° C, coupled with an Agilent 5973 Network mass spectrometer operated in electronic ionisation (EI) mode (70 eV). The mass range was scanned in the range of m/z 50 - 600 in a total cycle time of 1 s. The oven temperature of the GC was kept at 50° C for 1 min, and then raised of 10° C/min until 300° C and kept constant for 15 min. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1 ml/min. Compounds were identified partially by their retention time, based on comparisons with analysed reference compounds, and by their mass spectra, interpreted manually with the aid of the NIST Mass Spectral Library.

Results and Discussion

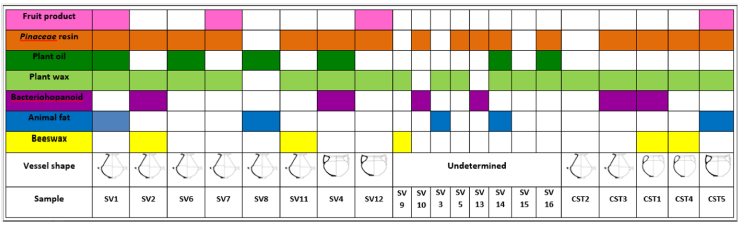

Organic compounds were preserved in most of the samples except for a few sherds containing low lipid content, probably due to degradation or a short life use of the vessels. Different mixtures of organic substances were present in the investigated pottery shapes (Table 1): fatty acids, terpenes, carboxylic compounds, sterols.

Table 1:Organic substances identified in the local matt-painted pottery from Castello di Alceste (SV) and Castelluccio (CST) according to vessel shapes.

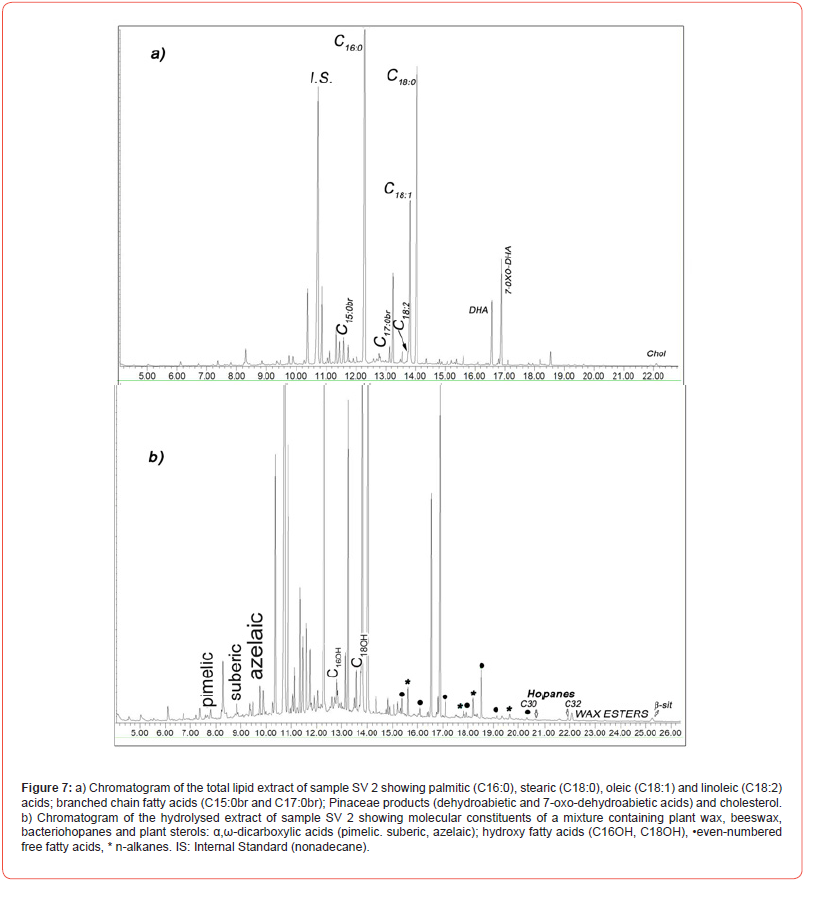

The analyses of the total lipid extracts (a) show appreciable concentrations of oleic acid (C18:1), followed by palmitic (C16:0) and stearic (C18:0) acids, together with plant sterols, mainly stigmasterol and β-sitosterol. The detection of α,ω-dicarboxylic acids, with a dominance of azelaic acid, a degradation product usually deriving from oleic acid, together with hydroxycarboxylic fatty acids, considered oxidation products of unsaturated fatty acids, suggest the presence of lipids derived from plant waxes, which are commonly present in the leaves of fruits, vegetables and cereals [22]. Their presence along with the simultaneous occurrence of oleic and linoleic acids in some samples, could indicate a plant derived oil [23, 24]. These samples display also an abundance of saturated fatty acids together with branched chain fatty acids and cholesterol, suggesting the presence of animal fats [25] (Figure 7a).

The detection of odd-numbered n-alkanes (C₂₁–C₃₃, with C27 dominant), even-numbered free fatty acids (C₂₂–C₃₀), long-chain palmitate wax esters (C₄₀–C₅₂) in five samples (Figure 7b) indicates the presence of beeswax [26], which could have been used for flavouring the content or waterproofing the vessels. Its presence could also suggest the use of honey for the production of mead as a fermented beverage, although the low quantities identified would exclude this hypothesis.

Moreover, in the majority of samples diterpenoid compounds were identified: dehydroabietic acid, didehydroabietic acid and 7-oxo-dehydroabietic acid, the major constituents and transformation products of Pinaceae resins [27]. Resins could have been used as a sealant to waterproof the ceramic containers or as an additive to preserve the content.

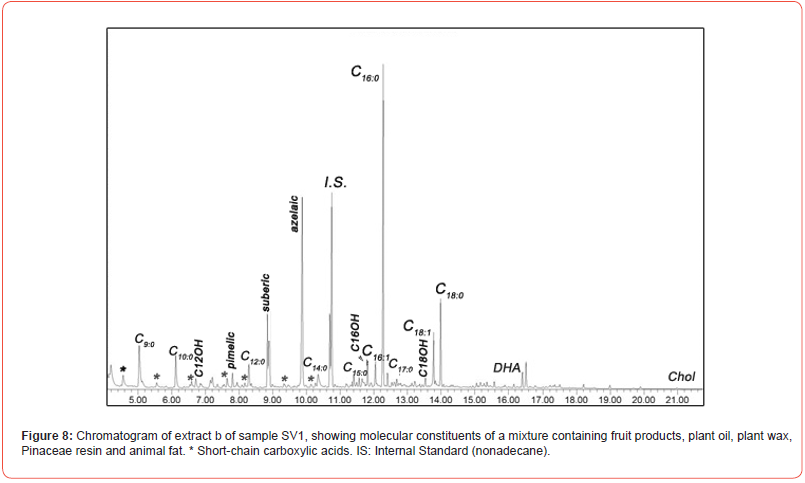

Short-chain carboxylic acids (succinic, fumaric, malic and vanillic acid) indicating the presence of fruit products were identified only in four samples in the absence of exogenous contamination (Figure 8). Considering that these biomarkers are ubiquitous compounds highly soluble in water, their presence in a few samples cannot be diagnostic for fermented beverages but it can simply indicate the addition of fruits or a reuse of the vessels. For these reasons, the identification of compounds as biomarkers of alcoholic beverages needs to be corroborated by further analyses on more archaeological samples together with the analyses of samples allowing negative control [28].

More interesting is the identification of a series of compounds corresponding to hopanes in the lipid extracts obtained from the interior surface of five vessels (Figure 7b). These compounds were absent in the exterior surfaces and sediment control samples. Bacteriohopanoid markers generally occur in bitumen [29], but they have been recently associated with bacterially-fermented alcoholic beverages such as pulque from Agavaceae plants [30], and beer from millet or barley [31]. The identification of hopanoids in vessels for liquid consumption recovered from stratigraphic contexts associated with tableware and commensal activities supports the hypothesis of the presence of fermented beverages rather than bitumen. Furthermore, use wear analyses evidenced pitting and corrosion on the interior walls of the pottery sherds in which bacteriohopanoids were identified. The association with plant oil/wax, Pinaceae resin and/or beeswax, indicates the variety of ingredients that could have been used in the production of fermented beverages, probably a beer preparation, considering the large quantities of cereals attested in the botanical record.

Conclusion

This preliminary study on Iapygian consumption practices through organic residue analyses gave the earliest evidence on the possible production and consumption of fermented beverages among Iron Age native communities of southern Italy, as suggested also by pitting and corrosion observed on the interior surfaces of the vessels. Different natural organic products have been identified, including plant waxes and oils, Pinaceae products, beeswax, indicating the ingredients used in the preparation of a possible cereal-based fermented beverage. Although no specific cereal biomarkers were identified in the analysed samples, the detection of bacteriohopanoids in the samples with corroded internal walls and the botanical data support the hypothesis of beer preparation. The archaeological identification of beer is difficult due to the low content of stable chemical lipid compounds. However, carboxylic acids and hopanoids can be markers for a bacterial induced fermentation.

The presence of beeswax and Pinaceae products indicates the addition of other ingredients, while plant waxes can be associated to the original plant products used to prepare the beverage. The presence of animal fats and fruits can also be related to vessel reutilization.

Further analyses on a larger corpus of locally produced wares integrated with botanical data and use wear study probably will contribute to reinforce these preliminary results providing also comparative data to identify consumption practices related with the status of social groups and the use of feasting spaces through the spatial distribution of the vessels.

The adoption of this interdisciplinary approach also will allow investigating the role of commensal practices and alcohol production/consumption within the emergence of social distinction, cultural expansion and exchange among the native communities of the Salento peninsula.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank staff members of the Laboratory of Synthetic Organic Chemistry of the University of Salento for their assistance in the analysis of the samples.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest

References

- Semeraro G (2015) Organizzazione degli abitati e processi di costruzione delle comunità locali nel Salento tra IX e VII sec.a.C. in: Burgers GJ, Saltini Semerari G (eds.), Social Change in Early Iron Age Southern Italy. Proceedings of the International Workshop, Rome 5-7 May 2011, Papers of Royal Netherlands Institute in Rome, Rome, Italy 63: 204-219.

- Semeraro G (2017) Dinamiche relazionali ed identitarie nell’orizzonte iapigio di età Contesti e materiali: l’area messapica settentrionale. In: Atti Taranto 54, Taranto 25-28 Settembre 2014, Taranto, Italy, pp. 317-329.

- Semeraro G (2022) Methods and practices in studies of the economy of Messapia, in D'Andria F, Semeraro G (eds.), Messapia: Economy and Exchanges in the Land between Ionian and Adriatic Sea: Panel 3.9, Heidelberg: Propylaeum, 2022 (Archaeology and Economy in the Ancient World – Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Classical Archaeology, Cologne/Bonn 2018, Band 12), pp. 3-16.

- Semeraro G (2016) Nuovi orizzonti per nuove comunità. Qualche riflessione sui processi di definizione delle società arcaiche della Puglia meridionale. In L Donnelan, V Nizzo, GJ Burgers (eds.), Contexts of Early Colonization Acts of the Conference, pp. 351-370.

- GJ Burgers, JP Crielaard (2016) The Migrant’s Identity: ‘Greeks’ and ‘Natives’ at L’Amastuola, Southern Italy, in L Donnellan, V Nizzo, GJ Burgers (eds.), Conceptualising early Colonisation, Bruxelles-Brussel-Roma, 2016, pp. 225-238.

- G Semeraro (2019) Archeologia delle cerimonialità nelle comunità preromane della Puglia meridionale. Contesti e materiali, in I. E. Buttita, S. Mannia (edd.), Il sacro pasto. Le tavole degli uomini e degli dèi (Atti del Convegno internazionale, Noto 26-28 ottobre 2017), Palermo, pp. 467-473.

- A Corretti, G Dinielli, M Merico (2010) Roca Indizi di attività cerimoniali dell’età del Ferro, in ASNP, s. 5, 2(2): 160-180.

- A Corretti, G Dinielli, M Merico (2017) L’età del Ferro nel sito di Roca: la ripresa delle relazioni transadriatiche e le evidenze di attività rituali, in Preistoria e Protostoria della Puglia (Studi di preistoria e protostoria 4), Firenze 2017, pp. 565-571.

- F D’Andria (2012) Il Salento nella prima Età del Ferro (IX-VII sec. a.C.): insediamenti e contesti, in ACMG L, Taranto, pp. 551-592.

- R Caldarola (2012) Ricerche archeologiche a Vaste, Fondo Melliche: l’età del Ferro, in R D’Andria, K Mannino (a cura di), Gli allievi raccontano, Atti dell’incontro di studio, Cavallino, 29-30 gennaio 2010, Galatina, 2012, pp. 65-78.

- Dietler M (2006) Alcohol: Anthropological/Archaeological Perspectives. Ann Rev Anthrop 35(1): 229-249.

- Dietler M, Hayden B (Eds.), (2001) Feasts: Archaeological and Ethnographic Perspectives on Food, Politics, and Power. Washington, D.C, USA.

- Wilson TM (Ed.) (2005) Drinking Cultures: Alcohol and Identity. Oxford.

- Yntema DG (1990) The Matt-Painted Pottery of Southern Italy, Ultrecht.

- Arthur JW (2002) Pottery Use-Alteration as an Indicator of Socioeconomic Status: An Ethnoarchaeological Study of the Gamo of Ethiopia. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 9(4): 331-355.

- Forte V (2022) Use activities, wear mechanisms and residues: the use alterations variability on pottery in light of the latest research advancements. Pottery Function and Use: A Diachronic Perspective (Ed. J Vuković and V Bikić), Belgrade, pp. 13-36.

- Arthur JW (2003) Brewing beer: status, wealth, and ceramic use alteration among the Gamo of south-western Ethiopia. World Archaeology 34(3): 516-528.

- MM Homan (2004) Beer and Its Drinkers: An Ancient near Eastern Love Story. Near Eastern Archaeology 67(2): 84-95.

- Semeraro G, Notarstefano F (2011).

- Mottram HR, Dudd SN, Lawrence GJ, Stott AW, Evershed RP (1999) New chromatographic, mass spectrometric and stable isotope approaches to the classification of degraded animal fats preserved in archaeological pottery. Journal of Chromatography A 833(2): 209-221.

- Pecci A, Giorgi G, Salvini L, Cau MÁ (2013) Identifying wine markers in ceramics and plasters using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Experimental and archaeological materials. JAS 40(1): 109-115.

- Ribechini E, Modugno F, Colombini MP, Evershed RP (2008) Gas chromatographic and mass spectrometric investigations of organic residues from Roman glass unguentaria. J Chromatography A 1183(1-2): 158-169.

- Copley MS, Bland MA, Rose P, Horton M, Evershed RP (2005) Gas chromatographic, mass spectrometric and stable carbon isotopic investigations of organic residues of plant oils and animal fats employed as illuminants in archaeological lamps from Egypt, Analyst 130(6): 860-871.

- Cramp L, Evershed R (2015) Reading the residues: chromatographic and mass spectrometric techniques for the reconstruction of artefact use in Roman Antiquity.’ In Ceramics, Cuisine and Culture, Oxford: Oxbow books.

- Pollard AM, Carl P Heron (2008) Archaeological Chemistry. Cambridge.

- Regert M, Colinart S, Degrand L, Decavallas O (2001) Chemical alteration and use of beeswax through time: accelerated ageing test and analysis of archaeological samples from various environmental contexts. Archaeometry 43(4): 549-569.

- Colombini MP, Modugno F, Ribechini E (2005) Direct exposure electron ionization mass spectrometry and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry techniques to study organic coatings on archaeological amphorae. Journal of Mass Spectrometry 40(5): 675-687.

- Drieu L, Rageot M, Wales M, Stern B, Lundy J, et al. (2020) Is it possible to identify ancient wine production using biomolecular approaches? STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research 6(1): 16-29.

- Connan J, Nieuwenhuyse OP, van As A, Jacobs L (2004) Bitumen in early ceramic art: bitumen-painted ceramics from Late Neolithic Tell Sabi Abyad (Syria). Archaeometry 46(1): 115-124.

- Correa-Ascencio M, Robertson IG, Cabrera-Corte´s O, Cabrera-Castro R (2014) Evershed RP. Pulque production from fermented agave sap as a dietary supplement in Prehispanic Mesoamerica. PNAS 11(39): 14223-14228.

- Rageot M, Mötsch A, Schorer B, Bardel D, Winkler A, et al. (2019) New insights into Early Celtic consumption practices: Organic residue analyses of local and imported pottery from Vix-Mont Lassois. PLoS ONE 14(6): e0218001.

-

Florinda Notarstefano*, Serena Perrone, Francesco Messa, Grazia Semeraro. Early Evidence for Alcohol Consumption in Iron Age Messapia (Southern Italy) through Organic Residue Analysis, Use-Alteration Traces and Vessel Morphology. Open Access J Arch & Anthropol. 5(4): 2024. OAJAA.MS.ID.000619.

-

Mineralogical, Petrographic groups, Emperor Claudius’, Phyllite, Tripod-bowls studied

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.