Research Article

Research Article

Window Design of Fashion Storefronts: Its Impact on Consumer Behavior

Erhard Lick*

ESCE International Business School, Paris - INSEEC U Research Center, France

Erhard Lick, Department of Marketing, Communication & Business Sales, ESCE International Business School, Paris - INSEEC U Research Center, France.

Received Date: May 14, 2021; Published Date: July 12, 2021

Abstract

This article provides an overview of the literature examining the influence of window design of fashion storefronts on consumer behavior, like store entry propensity. While research has shed light primarily on the impact of store-interior cues (e.g. sound, color, scent, or design features) on consumer behavior, research on the influence of store exterior cues (wall-mounted flags, entrance, or parking) on consumer behavior, has only recently built up momentum. In view of storefront windows, not only design elements, such as mannequins, verbo-visual relations, and the number of products displayed, have been investigated, but also conceptual models have been devised. Future research should keep focusing on the store exterior, and especially, storefront windows. The use of smart technologies in storefront windows needs particular attention.

Keywords:Fashion stores; Storefront windows; Visual merchandising; Consumer behavior

Introduction

The objective of this article is to give an overview of the extant literature investigating the impact of storefront window design on consumer behavior, especially in view of fashion stores. In general, one distinguishes between the interior and exterior of retail stores. According to Kotler P [1] both store interiors and exteriors can arouse specific emotional responses in customers and, consequently, can have an important influence on their purchase behavior. Kotler [1] has coined the term ‘atmospherics’, which he has defined as “the effort to design buying environments to produce specific emotional effects in the buyer that enhance his purchase probability”.

Expanding on the term ‘atmospherics’, Bitner MJ [2] has developed the concept of ‘servicescape’. Bitner MJ [2] has created a framework describing the impact the built environment (i.e. the physical surrounding created by people, in contrast to the natural or social environment) may exert on consumers and employees in service organizations. In a revised version of her framework, Bitner MJ [3] has included the social environment as a determinant of the servicescape.

Gottdiener M [4] argues that the rise in competition has brought about an increase in themed servicescapes and illustrates his argument with examples of restaurants, shopping malls, and casinos. Likewise, Diamond J, et al. [5] emphasize the importance of the use of themes in visual merchandising, especially in the highend market. Foster J, et al. [6] have found that themed servicescapes are more effective in terms of shopping enjoyment, positive brand attitudes, and brand loyalty, compared to similar non-themed servicescapes.

Until recently, the research stream on retail environments and their impact on consumer behavior has largely concentrated on in-store cues, such as lighting, sound, color, design features, scent, and signage [7-18]. For a review, refer to Turley W, et al. [19] [48]. In view of the dominance of research conducted on in-store retail environments, Turley W, et al. [19] demand that more attention be paid to the exterior of retail environments. The reason is that the exterior usually represents the first cues which consumers experience. For Turley W, et al. [19] the effective management of exterior sensory cues is a prerequisite for customers’ approach behavior. In general, the store exterior consists of the storefront, storefront displays (A-boards, wall-mounted flags, column stands, standing flags), entrances (revolving-, manual-, sliding-, or automatic swing doors), display windows, parking, physical characteristics of the building (design, height, size, and color), location (congestion and traffic), surrounding area including landscaping and vegetation, as well as stores in the vicinity [20,21]. The need for more research on the external retail environment, and especially, storefront window displays, has been supported by Oh H, et al. [22], Moore CM, et al. [23], as well as Lange F, et al. [24]. Hence, in the following, the literature on storefront window displays and their influence on consumer behavior is presented. The literature review is divided into two parts: first, it sheds light on the design elements investigated; second, is points out in some detail the conceptual models which have been developed in this research stream.

Storefront Window Displays and Consumer Behavior

The visual appeal of the store exterior forms an immediate impression on the part of the customers and, therefore, represents an essential factor for customers to decide whether they enter a store or not [22] [34] (Oh and Petrie, 2012). What is more, store windows, due to their location at the point of purchase, potentially impact purchase decisions [25]. In addition, window display design reflects a retailer’s image [26]. Store windows may create entertainment, engagement and inspiration on the part of customers and may help them to establish an association and relationship with the retailer’s brand [27]. Window displays constitute a pivotal source of information in the external retail environment for the consumers’ decision-making process [25]. Several authors have focused on specific design elements of shop windows in their investigations on the relationship between window displays and consumer behavior.

Design elements

Edwards S, et al. [26] have ascertained that the size of window displays correlates positively with consumer interests: the larger the window displays, the higher consumers’ approach behavior. Cornelius et al. [28] have explored the impact of storefront displays (A-boards, wall-mounted flags, column stands, and standing flags) on store image. They have found that innovative displays achieve better image ratings than traditional ones. Furthermore, the presence of storefront displays generally exerts a positive influence on store image.

Yildirim K, et al. [29] have revealed that shoppers prefer flat windows over arcade windows in relation to promotion, merchandise and fashion, as well as show a higher store entry and purchase intention in relation to flat windows. This positive perception appears to be more pronounced among men than among women. Jain V, et al. [30] have stressed the importance for women to gain pleasure from shop windows, which they have referred to as “feel-good factor”. This factor is positively correlated to women’s purchase intent.

Velasco Vizcaíno F [31] have analyzed the influence of window signs on patronage intentions. In an experiment, subjects were randomly shown one of two pictures, each depicting the same restaurant storefront. The difference between these two pictures was that in one picture the storefront showed a special form of window signs, namely captions, promoting the menu and brunch specials, while in the other picture this was not the case. The results have demonstrated a positive connection between the application of captions and store patronage intentions.

The role of verbal elements in storefront windows has also been investigated by Lick E, et al. [32]. They argue that the use of verbal cues may not be confined to convey promotional messages, like ‘clearance sales’, but may be applied to generate a meaningful interplay with visual cues (e.g. mannequins and props). They determined three levels of complexity of verbo-visual interplays, with complexity being defined as the cognitive elaboration needed to decode the message of the store window. Their results have shown that store window designs of medium complexity lead to consumers’ relatively highest store entry propensity.

Lindström A, et al. [33] have sought to determine whether the presence or absence of a head on a mannequin in a shop window has an influence on shoppers’ purchase propensity. They contend that mannequins with heads seem to lead to higher purchase propensity of the merchandise displayed on mannequins compared to mannequins without a head. This effect appears to be particularly true for novice consumers, who have little fashion knowledge, since mannequins with heads help them to envision themselves wearing the clothes on display in the window. However, in the case of expert consumers, mannequins without heads seem not only to increase purchase intentions, but also to facilitate the envisioning of wearing the clothes on display.

Yim MYC, et al. [34] have explored the display height of mannequins as well as their distance to shoppers. They have concluded that for customers with a dominant hedonic shopping motivation (e.g. shopping for clothes or perfumes) a mannequin displayed up high produces higher purchase intentions compared to situations where mannequins are displayed down low or on the floor. For customers with a dominant utilitarian shopping motivation (e.g. shopping for sportswear), mannequins need to be positioned not only up high, but also close to customers.

Larceneux F, et al. [35] who investigated jewelers’ store windows, concluded that an increase in the number of products exhibited in a window has a positive effect not only on the price image but also on the customers’ feeling of having a large choice. However, an exceedingly large number of products negatively influences the attractiveness of the window, customers’ perception of quality and the originality of the products, as well as customers’ inclination to make a choice. Likewise, according to Mortelmans D [36], luxury boutiques and stores apply the strategy of emptiness in their windows to generate a connotation of luxury and exclusiveness of their store and brands.

Kernsom T, et al. [37] have revealed that in reference to jewelry and fashion products shown in store windows, the depiction of a presenter wearing the products for sale in the window, a large window size, and a decoration with props impact customers from an affective, cognitive, and conative perspective. Moreover, Somoon K, et al. [38] have found that both spotted lights and props are the most essential visual cues in relation to perceived complexity, purchase intent, and shop attractiveness. Somoon K, et al. [39] have concluded in their study on the window design of stores selling Thai crafts products that spotlighting and warm colors have the biggest influence on purchase intention.

Apart from the exploration of various design elements, other researchers have presented conceptual models and typologies with respect to storefront windows.

Conceptual models

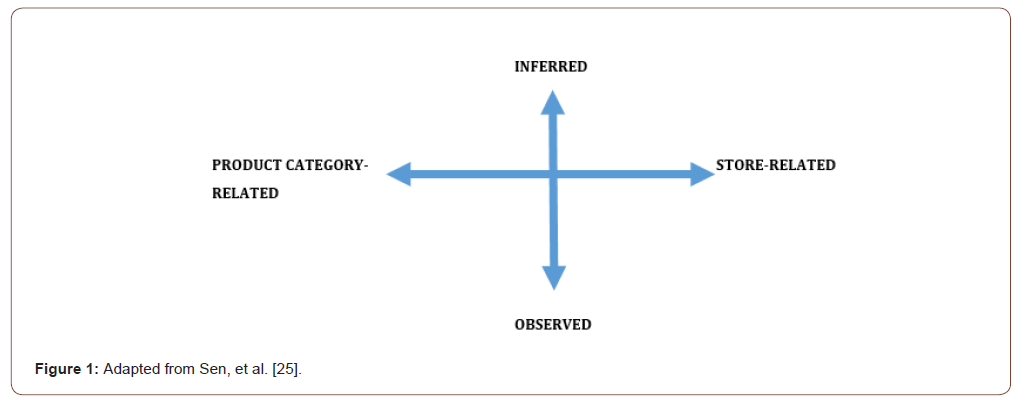

Sen S, et al. [25] distinguish between two dimensions of information which customers can acquire from store windows. The first dimension represents a continuum which goes from product category-related information (e.g. latest fashion trends/innovations, price level of products, brands, or quality of merchandise) to storerelated information (e.g. retailer’s image or retailer’s creativeness). The second-dimension ranges from observed information, which is obvious from the window (e.g. promotional announcements, such as ‘sale’ or ‘new arrivals’ and product features) to inferred information, derived from visual cues (e.g. retailer’s image or product-fit). Product-fit refers to customers who mentally try on the fashion items on display and infer whether they would fit them (Figure 1).

Sen, et al. [25] have concluded that customers seeking inferred information, such as store image and product-fit information, show a higher propensity to enter a store, compared to customers searching for observed information, like information on merchandise, promotions, and fashion. They argue that the search for information on the store image may entice customers to enter the store in order to browse and collect more information on the store and its merchandise, whereas the search for product-fit information may tempt them to examine and/or buy the items they have seen in the shop window. Moreover, their study has demonstrated that customers who gather product category-related information (e.g. new fashion trends) are more inclined to make purchases influenced by store windows. In contrast, customers who rather search for store image information show a higher propensity to enter the store, but are less likely to make purchases based on store windows.

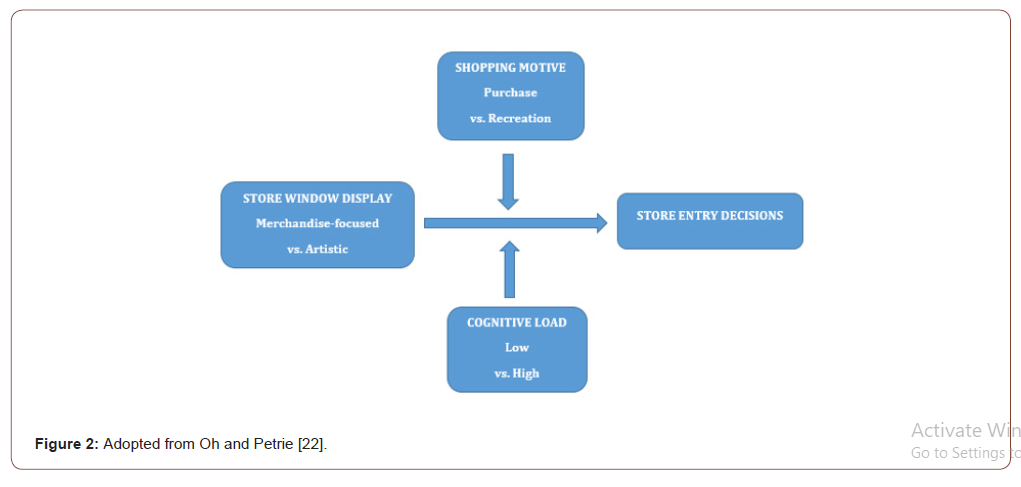

Oh H, et al. [22] have investigated how customer perception of store window displays interacts with both their shopping motives (purchase versus recreational) and the limits of their information processing capacity (low versus high cognitive loads) in relation to shop entry decisions (Figure 2). Oh H, et al. [22] have presented a dichotomy of two types of store window displays: merchandise-focused versus artistic displays. Merchandisefocused displays convey concrete messages and, therefore, enhance the comprehension of the merchandise itself, so that customers are lured into the store. In contrast, artistic displays convey abstract messages whose purpose is to arouse shopper curiosity and, subsequently, their urge to further explore the items on display in the store. The main goal of artistic window displays is to show the store image and to attract shopper attention. In fact, designers and merchandisers only have a few seconds to create curiosity [40,41] and to generate ‘stopping power’. Kernsom T, et al. [37] have compared the eye-catching power of store windows with that of magazine covers. Or as Alannah Weston, the deputy chairman of the high-end UK retailer Selfridges, has put it: “If Selfridges were a magazine, the windows would be the front cover”. Oh H, et al.’s [22] distinction of ‘purchase motives’ versus ‘recreational motives’, which they consider moderating variables in their framework, is based on Kaltcheva VD, et al. [13] typology of ‘taskoriented motivational orientation’ and ‘recreational motivational orientation’. While the first type of motives refers to consumers who are searching and shopping for specific products, services, and information, the second type of motives is based on the consumers’ aim to primarily gain inherent satisfaction from the shopping activity itself. Finally, Oh H, et al. [22] differentiate between high and low cognitive loads, with ‘cognitive load’ being defined as “the load on working memory used for information processing”. They created different cognitive load conditions in their study by asking the respondents to remember a two-digit number (low cognitive load condition) or a seven-digit number (high cognitive load condition). Subsequently, the respondents were asked to decide on their entry propensity with respect to two different store window displays they were shown [22]. They argue that customers’ mental capacities in relation to the decoding of messages shown in store windows constitute a moderating variable with respect to the influence of the window display type on store entry decisions. Their study has shown that in the case of low cognitive load conditions neither merchandise-focused nor artistic window displays have an impact on store entry decisions. Yet, under high cognitive load conditions the artistic shop window has a negative influence on store entry decisions, due to the fact that consumers may have difficulty in comprehending the meaning of the display [22].

Lange F, et al. [24] have demonstrated that the creative design of store windows has a positive influence on store entry. They argue that this effect can be explained by shopper attitudes towards the store window itself, their product beliefs towards the items displayed, and their perceived retailer effort. Moreover, the influence of creativity on store entry seems to be higher when the shopper visits the retailer less frequently. Similarly, Roozen I [42] has shown that ‘complex’, i.e. creative, window designs lead to higher store entry intentions compared to ‘simple’ window designs.

Table 1 provides, in chronological order, an overview of the literature about the influence of store window design on consumer behavior.

Table 1:Overview of the research about the relation between store window design and consumer behavior.

Smart Storefront Windows

Research on the use of smart technologies, like IoT (Internet of Things), in retailing has recently emerged [43-45]. According to Adapa S, et al. [46], shoppers’ perception of the advantage and innovativeness of smart retail technologies increases their perceived shopping value and, in turn, their store loyalty.

Hwangbo H, et al. [47] define smart fashion stores as offline retail stores which apply smart technologies (e.g. facial recognition, augmented reality, or interactive digital signage) to “create immersive, authentic user experiences for customers”. They distinguish between smart technologies employed in the store interior, like smart hangers or smart mirrors, and smart technologies used in storefront windows. In view of storefront windows, Pantano E [48] has found some evidence of consumers’ positive reactions to touch screens and other interactive technology mounted on windows of fashion stores. Consumers may derive both hedonic and functional benefits, e.g. the opportunity to choose an item before entering the store, from such a technology. Similarly, Lecointre- Erickson, et al. [49] have concluded that interactive window displays impact consumer arousal. More specifically, according to Pantano E, et al. [50], innovative interactive technologies increase consumer willingness to enter a store and create positive wordof- mouth. Cremonesi, et al. [51] have explored the effect of smart light technology in storefront windows on shopper experiences in comparing three different light configurations: static, dynamic, and interactive. They have found that interactive smart lights raise store attractiveness and shopper engagement as well as enhance shopping experiences.

Conclusion

While the retail literature has been traditionally examining which impact cues in the interior of fashion stores exert on consumer behavior, current research has paid particular attention to the influence of cues in the store exterior on consumer behavior. However, this article has given evidence that the literature on the role of window design in fashion storefronts is rather scarce. Moreover, the application of smart technologies, such as IoT, in storefront windows has only recently been put under investigation. Therefore, it can be concluded that future research should continue to focus on the store exterior, and especially, storefront windows. At the same time, research on the use of smart technologies in storefront windows needs to be intensified.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ibn-Mohammed T, Mustapha KB, Godsell J, Adamu Z, Babatunde KA, et al. (2020) A critical review of the impacts of COVID-19 on the global economy and ecosystems and opportunities for circular economy strategies. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 164: 105169.

- Khlaif ZN, Salha S, Fareed S, Rashed H (2021) The hidden shadow of Coronavirus on education in developing countries. Online Learning 25 (1): 269-85.

- El Said, Ghada Refaat (2021) How Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Affect Higher Education Learning Experience? An Empirical Investigation of Learners’ Academic Performance at a University in a Developing Country. Advances in Human-Computer Interaction.

- Darling-Hammond L, Flook L, Cook-Harvey C, Baron B, Osher D (2020) Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science 24(2): 97-140.

- Kim S, Seong H, Her Y, Chun J (2019) A study of the development and improvement of fashion products using a FDM type 3D printer. Fashion and Textiles 6: 9.

- Kwon YM, Lee YA, Kim SJ (2017) Case study on 3D printing education in fashion design coursework. Fashion and Textiles 4: 26.

- Papachristou E, Chrysopoulos A, Bilalis N (2020) Machine learning for clothing manufacture as a mean to respond quicker and better to the demands of clothing brands: a Greek case study. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology: 12.

- Singha K, Kumar J, Pandit P (2019) Recent Advancements in Wearable & Smart Textiles: An Overview. Materials Today-Proceedings 16(3): 1518-1523.

- Park M, Im H, Kim DY (2018) Feasibility and user experience of virtual reality fashion stores. Fashion and Textiles 5: 32.

- Shou D, Fan J (2018) An all hydrophilic fluid diode for unidirectional flow in porous systems. Advanced Functional Materials 28(36): 1800269.

-

Erhard Lick. Window Design of Fashion Storefronts: Its Impact on Consumer Behavior. 8(4): 2021. JTSFT.MS.ID.000695.

-

Fashion stores, Storefront windows, Visual merchandising, Consumer behavior

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.