Research Article

Research Article

What’s in an Orange? Squeezing Value from Agricultural Waste into Sustainable Populuxury Fashion and IP Strategy

Marlena Jankowska1*, José Geraldo Romanello Bueno2 and Mirosław Pawełczyk3

1Director of the Center for Design, Fashion and Advertisement Law at the University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland

2Mackenzie Presbyterian University in São Paulo, Brazil; Member of the Center for Design, Fashion and Advertisement Law at the University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland

3Director of the Research Center for Public Competition Law and Sectoral Regulations at the University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland

Marlena Jankowska, Director of the Center for Design, Fashion and Advertisement Law at the University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland

Received Date: September 11, 2024; Published Date: November 21, 2024

Abstract

This study explores the integration of sustainability with luxury and premium fashion, coining the term “populuxury” to describe this phenomenon. By examining the strategic management of intellectual property among leaders like Orange Fiber, the research identifies how fashion brands are adapting to and promoting environmental stewardship. This approach is reshaping industry standards and consumer expectations, with implications for both market practices and academic theory on apparel consumption in the age of sustainability.

a) Purpose: This study examines the concept of “populuxury” within sustainable fashion, aiming to uncover how luxury strategies intersect with sustainability, thereby redefining contemporary fashion consumption and reshaping intellectual property practices.

b) Design/Methodology/Approach: Employing a desk-based research methodology, the study systematically analyzes data from various legal, commercial, and academic sources, including the WIPO, EUIPO and EPO databases, to understand the strategic management of intellectual property in the sustainable textile industry.

c) Findings: Results indicate that companies like Orange Fiber are pioneering the integration of sustainability into luxury fashion, using intellectual property strategies to secure their innovations and competitive edge. These efforts are setting new industry benchmarks and transforming consumer expectations toward sustainability in luxury goods.

d) Originality: The study introduces the concept of “populuxury,” providing a novel perspective on the evolving dynamics between luxury markets and sustainable practices. It contributes to both academic discourse and practical applications by detailing how luxury brands are navigating the increasing demands for sustainability.

Introduction – Populuxury Explained: Redefining Oranges and Luxury Through Sustainability

The term “populuxury” is an emerging concept in socioeconomic discourse, capturing the intersection between popular culture and luxury consumption. This term is particularly relevant in the context of globalized economies, where the boundaries between mass-market goods and luxury products are increasingly blurred. In recent decades, the luxury goods market has undergone significant transformation, driven by globalization, technological advancements, and shifting consumer behaviors. Traditional luxury, characterized by exclusivity, craftsmanship, and high price points, has historically been the domain of the elite. However, as consumer aspirations evolve and markets expand, a new form of luxury has emerged—one that is accessible to the masses yet retains an aura of exclusivity [1]. Populuxury also offers a compelling framework to address the advancements in sustainable fashion, particularly in the context of innovations such as clothing made from food by-products, floral-based textiles, and fashion technology (fashtech) [2-5]. For instance, Orange Fiber, an Italian company, has pioneered a method of producing high-end silk-like fabrics from the by-products of citrus juice production. This innovation not only addresses the issue of agricultural waste but also creates a sustainable luxury textile that has been embraced by luxury brands such as Salvatore Ferragamo [6]. Similarly, Vegea, another Italian innovator, produces vegan leather from grape marc, a by-product of wine production, which has been adopted by luxury fashion brands like H&M’s Conscious Collection and Bentley for their car interiors.

Another example is Pangaia, a brand that has revolutionized sustainable luxury by introducing clothing made from wildflowers, seaweed fiber, and other bio-based materials. Their FLWRDWN™ technology, which uses wildflowers instead of traditional down feathers, exemplifies how populuxury is not just about aesthetics but also about pioneering environmentally friendly alternatives that appeal to the modern, conscious consumer [7]. These advancements in sustainable fashion resonate strongly with consumer values, particularly among younger, more environmentally conscious demographics. According to recent studies, a significant portion of consumers, especially millennials and Gen Z, are willing to pay a premium for sustainable fashion. In a 2022 report by McKinsey & Company, nearly 67% of respondents indicated that they would be willing to pay more for products made from sustainable materials. This willingness to invest in sustainable luxury highlights the growing importance of ethical considerations in consumer purchasing decisions, aligning with the populuxury trend where luxury is not only defined by exclusivity and craftsmanship but also by its sustainability credentials [8-11]. In response, luxury brands are increasingly incorporating sustainable practices and materials into their offerings to meet this demand. Stella McCartney, a longtime advocate for sustainable fashion, has partnered with Bolt Threads to create luxury garments from Mylo™, a mycelium-based leather alternative that is both sustainable and luxurious [12]. This integration of innovative, eco-friendly materials into highend fashion exemplifies how populuxury is reshaping the luxury market.

Method

This study employs a rigorous desk-based research methodology to explore the concept of populuxury, with a specific focus on its implications within the realm of sustainable fashion. The methodology integrates qualitative methods, drawing on a wide range of secondary sources to provide a nuanced understanding of the intersection between luxury strategies and sustainability. The primary approach involved comprehensive desk-based research, systematically gathering and analyzing data from legal, commercial, and academic sources. Legal frameworks and intellectual property issues were examined through databases such as those of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), Eropean Patent Office (EPO) and the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO). These sources were instrumental in elucidating the legal protections surrounding innovations in sustainable fashion, such as those pioneered by Orange Fiber and Vegea, which are at the forefront of developing sustainable luxury materials. Concurrently, an extensive literature review was conducted, encompassing academic articles, industry reports, and case studies. This review provided a theoretical foundation for the study, particularly regarding the evolution of luxury markets, consumer behavior in relation to sustainability, and the impact of technological advancements on luxury branding. The synthesis of this literature facilitated a deeper understanding of how populuxury is reshaping traditional luxury paradigms. The qualitative method was employed to interpret the Green WIPO data, with a focus on capturing the intricate dynamics of textile brand strategies within the populuxury framework. This method allowed for an in-depth analysis of how brands are responding to these evolving consumer expectations.

To systematically document the current state of populuxury, a descriptive approach was utilized, detailing specific examples of sustainable innovations within the luxury sector, such as the use of food by-products in textiles, floral-based materials, and the integration of fashion technology. Furthermore, an interpretative approach was employed to analyze the broader implications of these innovations for the luxury market. This involved critically examining how the incorporation of sustainability is redefining luxury, making it more accessible to a broader audience while preserving its exclusivity. Data analysis was conducted with a focus on identifying patterns and trends that highlight the transformative impact of sustainability on luxury branding. The analysis also considered the legal and regulatory dimensions of these innovations, particularly the role of intellectual property in safeguarding the competitive advantage of sustainable luxury brands. By combining these methodological approaches, the study offers a comprehensive and sophisticated examination of populuxury, providing insights into how luxury brands are strategically navigating the increasing demand for sustainability within the context of contemporary luxury consumption. This methodological framework ensures that the research is both thorough and analytically robust, capturing the complexity of the populuxury phenomenon. The fashion industry, historically synonymous with luxury and aesthetic innovation, has reached a pivotal moment where its significant environmental impact can no longer be ignored.

Harvesting Innovation in the Age of FashTech

The early 2000s saw the meteoric rise of fast fashion, a business model spearheaded by industry giants like Zara and H&M. These companies revolutionized the way fashion was produced and consumed, making trendy clothing accessible to a global audience at unprecedented speeds. However, this rapid production cycle came at a high environmental cost, leading to increased pollution, resource depletion, and waste. The situation reached a critical point with the heightened visibility of ultrafast fashion around 2017, led by brands such as Boohoo and ASOS. These companies took the fast fashion model to new extremes, capable of adding between 100 and 45,000 new products to their online stores each day. While the term “ultrafast fashion” gained significant attention in 2017, the practices that define this model had been developing for several years prior. This hyper-accelerated production process further exacerbated the industry’s environmental footprint, drawing intense criticism from environmental scholars, activists, and consumers alike [13]. In light of these challenges, a transformative movement known as “FashTech” has emerged, seeking to reconcile the fashion industry’s need for innovation with its responsibility to the environment [2- 5].

FashTech represents a fusion of fashion and technology, focusing on sustainable advancements across three distinct categories:

a. Digital technology

b. Physical technology, and

c. Biological technology [14-16].

Digital technology within FashTech is revolutionizing how fashion operates on multiple levels, from production to consumer interaction. One of the most significant innovations in this area is the application of blockchain technology to the fashion supply chain. Blockchain allows for unprecedented transparency, enabling brands and consumers to trace the origins and journey of textile fibers with precision. This ensures that materials are sourced sustainably, from certified suppliers who adhere to ethical practices. For example, a blockchain system could track the entire lifecycle of organic cotton, from the farm where it was grown to the factory where it was spun into fabric, providing a verifiable chain of custody that guarantees the cotton’s organic status. Another key digital innovation is the development of AI-driven virtual fitting rooms. These systems allow consumers to try on clothes virtually, reducing the need for physical samples and lowering return rates, which in turn diminishes the environmental impact associated with overproduction and transportation.

Physical technology in FashTech focuses on material innovation and manufacturing processes that minimize waste and environmental harm. One of the most groundbreaking developments in this area is 3D printing, which allows designers to create garments with precision, using only the exact amount of material needed. This zero-waste approach eliminates the traditional cut-and-sew waste associated with garment production. For instance, a designer using 3D printing can produce a dress that fits the wearer perfectly, with no fabric scraps left behind. Additionally, advancements in nanotechnology are enabling the creation of textiles that are not only durable and biodegradable but also self-cleaning, significantly reducing the need for frequent washing and the associated water and energy consumption. These materials can repel dirt and moisture, ensuring that garments stay clean longer, thereby extending their lifespan and reducing the overall environmental footprint.

Biological technology represents the cutting edge of FashTech, where science meets sustainability to create entirely new materials and processes. Companies like Orange Fiber are at the forefront of this movement, developing innovative textiles from unexpected sources. Orange Fiber’s flagship product is a luxurious fabric made from citrus waste, specifically the byproducts of Italy’s extensive juice industry. This process involves extracting cellulose from the peels and pulp left over after juice production, which is then transformed into a soft, silk-like fabric suitable for high-end fashion. This innovation not only addresses the significant issue of agricultural waste but also provides an eco-friendly alternative to traditional textiles like cotton and silk, which are resourceintensive to produce [16,17]. The impact of Orange Fiber’s work has been recognized at the highest levels of the fashion industry. In 2015, the company was awarded the prestigious Global Change Award by the H&M Foundation, an accolade often referred to as the “Fashion Nobel Prize”. The H&M Foundation, in partnership with Accenture and the KTH Royal Institute of Technology, established the Global Change Award to identify and support the most promising innovations in sustainable fashion [18]. Orange Fiber’s recognition in this context underscores the transformative potential of biological technology in redefining how fashion can be both luxurious and environmentally responsible.

The Global Change Award has spotlighted numerous innovations that align with the principles of FashTech. In 2020, the award was given to “Tracing Threads”, a project utilizing blockchain technology to track and verify the sustainability of textile fibers throughout the supply chain. This innovation exemplifies the integration of digital technology with sustainability goals, ensuring that every step of the production process is transparent and accountable. Another 2020 winner, “Zero-Waste Tailoring”, introduced a revolutionary approach to garment production using 3D printing technology. This method allows for the creation of garments without any waste, with the added benefit that these garments can be melted down and recycled into new products, creating a closed-loop system that aligns perfectly with circular economy principles. These innovations, along with Orange Fiber’s citrus-based textiles, are not just incremental improvements—they represent a fundamental shift in how the fashion industry can operate sustainably. By leveraging advanced technologies across digital, physical, and biological domains, FashTech is paving the way for a future where fashion is not only synonymous with style but also with environmental stewardship and ethical responsibility.

As we move forward, the fashion industry’s ability to adapt and integrate these FashTech innovations will be crucial. Companies like Orange Fiber are demonstrating that it is possible to reconcile the demands of fashion with the imperatives of sustainability, setting a new standard for the industry. The recognition and success of such companies suggest that the future of fashion lies not in perpetuating the wasteful practices of fast and ultrafast fashion but in embracing a model that prioritizes innovation, sustainability, and transparency. This transformation is not just necessary for the health of the planet but also presents a significant opportunity for the fashion industry to redefine itself in the 21st century, aligning with the growing consumer demand for products that are both stylish and sustainable.

From Waste to Wear: Leveraging Innovation and IP to Revolutionize Sustainable Fashion

R&D and Genesis of the Collaboration

The collaboration between Orange Fiber and Politecnico di Milano was a deep and multifaceted partnership that played a critical role in transforming a visionary idea into a pioneering innovation in sustainable fashion. The idea for Orange Fiber was conceived by Adriana Santanocito, who was inspired by the vast amounts of citrus waste produced by Italy’s juice industry. Recognizing the potential for this waste to be repurposed into a valuable resource, she envisioned creating a sustainable textile from citrus byproducts [16,17-19]. However, turning this idea into reality required advanced scientific and technical expertise, particularly in the fields of chemical engineering and materials science, which led to the collaboration with Politecnico di Milano, one of Italy’s most prestigious technical universities [16,17-19]. The collaboration began in 2012 when Santanocito approached Politecnico di Milano, specifically working with the Department of Chemistry, Materials, and Chemical Engineering “Giulio Natta”. “Giulio Natta” refers to the Department of Chemistry, Materials, and Chemical Engineering at Politecnico di Milano, which is named after the Italian chemist Giulio Natta. Natta was a Nobel Prize-winning scientist renowned for his work in the field of polymer chemistry. He received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1963, along with Karl Ziegler, for their discoveries in the field of high polymers, specifically for the Ziegler- Natta catalyst, which is crucial in the production of polymers like polypropylene and polyethylene. The university provided access to cutting-edge research facilities and a team of experts specializing in polymer science, cellulose chemistry, and textile engineering. The department’s focus on innovative materials and chemical processes aligns well with the goals of creating new, eco-friendly materials from agricultural waste.

Developing the Extraction Process

One of the primary challenges was developing a method to efficiently extract cellulose from citrus waste, particularly from the peels and pulp left after juice extraction [20-22]. The research team at Politecnico di Milano worked closely with Orange Fiber to optimize the chemical process needed to break down the pectin and other complex polysaccharides present in the citrus waste. This involved experimenting with various solvents and enzymatic treatments to isolate the cellulose fibers in a form that could be spun into yarn. The process required overcoming significant technical hurdles. Citrus peels contain a high percentage of water and oils, which complicate the extraction of pure cellulose [21,23,24]. The university’s researchers most likely have focused on developing a multi-step process that included:

a. Pre-treatment: To remove oils and impurities that could interfere with the extraction process.

b. Cellulose Isolation: Utilizing a combination of chemical treatments and mechanical processes to break down the peels and separate the cellulose.

c. Purification: Refining the cellulose to achieve the necessary purity and consistency required for textile production.

These steps were meticulously refined through a series of trials and iterative experiments [22,25]. Politecnico di Milano’s facilities allowed for small-scale testing of the extraction process, enabling the team to fine-tune the chemical reactions and process parameters until they achieved the desired quality of cellulose.

Fiber Spinning and Textile Production

Once the cellulose extraction process was optimized, the next challenge was to transform this raw material into a fiber suitable for textile production. This involved another set of complex processes, including dissolving the cellulose in a solvent to create a viscous solution [21-25], which could then be extruded through a spinneret to form continuous fibers-a process similar to the production of viscose rayon. The collaboration at this stage required significant input from the university’s experts in polymer processing and fiber technology. They worked on developing the precise conditions under which the cellulose solution could be spun into fibers with the necessary properties for textile use, such as strength, flexibility, and smoothness. The resulting fibers were then tested for their physical properties, including tensile strength, elasticity, and dye uptake, ensuring that they could meet the demanding standards of the fashion industry.

Testing, Validation and Sustainability

Politecnico di Milano played a crucial role in testing and validating the fabric produced from the citrus fibers. This included assessing the fabric’s performance in terms of durability, comfort, and environmental impact [23]. The university’s laboratories were equipped to conduct a range of tests, including:

a. Mechanical testing to evaluate the fabric’s strength and resilience.

b. Chemical testing to ensure the fabric was free from harmful substances and could be safely worn.

c. Environmental impact analysis to assess the overall sustainability of the production process, including energy consumption, water use, and the potential for recycling.

Compared to the production of natural cellulose fiber from cotton, the current process offers significant economic and environmental benefits. Producing 1 kg of cotton textile typically requires around 11,000 liters of water, with 45% of that water used for irrigation. In contrast, producing 1 kg of yarn from citrus fruit waste requires only about 800 to 1,000 liters of irrigation water, significantly less than cotton. Additionally, citrus fruit cultivation demands far fewer pesticides, with approximately 1.6 grams needed for 1 kg of citrus-based yarn, compared to about 127 grams of pesticides required for 1 kg of cotton [22]. The results of these tests were critical in proving that the Orange Fiber fabric was not only sustainable but also commercially viable as a high-quality textile suitable for the fashion industry [22].

Intellectual Property and Strategies

The successful development of the citrus-based textile led to the filing of a patent in 2013, with significant contributions from Politecnico di Milano in documenting the innovative process. The patent covered not only the specific chemical processes used to extract and purify the cellulose, but also the methods for transforming it into textile fibers. This comprehensive approach to intellectual property protection was crucial in securing the international PCT extension, which allowed Orange Fiber to safeguard its innovation across multiple countries.

Ownership of IP

In university-industry collaborations, particularly those involving groundbreaking innovations such as sustainable textiles from agricultural waste, the ownership of intellectual property (IP) is a critical aspect [20]. Typically, when university researchers are deeply involved in the R&D process, the university retains partial ownership of the resulting patents. This joint ownership can take several forms, but the most common is the university holding specific rights to the patent, which ensures they benefit [26] from any future commercial success. For example, if a company develops a new material based on research conducted at a university, the university may retain a share of the IP. This means that while the company may have the exclusive rights to commercialize the product, the university is entitled to receive a portion of the revenue, often through royalties. These royalties are generally a percentage of the gross or net sales of the product that utilizes the patented technology. The precise percentage can vary depending on the negotiation but typically reflects the university’s contribution to the development. Furthermore, the university might also retain the right to use the patented technology for further academic research or educational purposes. This clause is common in IP agreements and ensures that the university can continue to innovate and educate without infringing on the company’s commercialization rights.

Licensing Agreements

To commercialize the technology developed in collaboration with a university, the company usually enters into a detailed licensing agreement. This agreement outlines the terms under which the company can use the university’s IP [27]. Licensing agreements are often complex, tailored to reflect the specifics of the collaboration, the market potential of the technology, and the respective contributions of the parties involved. For instance, the company might pay the university an upfront licensing fee for the right to use the technology. This fee compensates the university for its initial research investment. Beyond this upfront payment, the agreement typically includes provisions for ongoing royalties, which are calculated as a percentage of the revenue generated from the commercialized product. These royalties ensure that the university benefits directly from the product’s market success. In addition to financial terms, the licensing agreement may include performance milestones. These milestones could be tied to sales targets, product launch timelines, or market expansion efforts. For example, the agreement might stipulate that the company must achieve a certain level of sales within a specified period, or it could trigger additional payments if the product is introduced into new international markets. Such milestones are designed to align the company’s commercial goals with the university’s interest in the successful deployment of the technology.

Research Funding and Continued Collaboration

To maintain and enhance the technological edge provided by the university’s research, the company often commits to ongoing research funding. This funding supports continued innovation and refinement of the technology [20]. It is not uncommon for these collaborations to extend beyond the initial project, leading to long-term partnerships where the company funds specific research initiatives that align with its commercial objectives. For example, the company might fund a research lab at the university that focuses on further developing the material or exploring new applications for the technology. This funding typically covers the cost of laboratory facilities, research personnel, and any necessary equipment or materials. The university benefits by having a steady stream of funding that supports its academic mission and research agenda, while the company gains continuous access to cuttingedge innovations that can be rapidly integrated into their product lines. Moreover, this ongoing collaboration may also include joint development agreements (JDAs), where both the university and the company work together on further projects. These agreements often specify how any new intellectual property resulting from the joint work will be owned and managed, ensuring both parties share in the benefits of future innovations.

Equity Stakes and Spin-Off Dynamics

In some collaborations, particularly those leading to the creation of a spin-off company, the university may negotiate an equity stake in the new venture. This equity stake reflects the university’s contribution to the development of the technology and its potential future value. For instance, if a spin-off company is established to commercialize a new sustainable textile developed through university research, the university might receive shares in the company. This equity stake gives the university a direct financial interest in the company’s success, providing potential dividends and appreciating in value as the company grows. The university might also negotiate a seat on the company’s board, giving it influence over strategic decisions. Equity stakes are especially valuable in highgrowth scenarios where the spin-off is expected to scale rapidly. For example, if the company successfully raises venture capital or goes public, the university’s equity could significantly increase in value, providing substantial financial returns. This arrangement aligns the university’s long-term financial interests with the company’s success, encouraging both parties to continue collaborating closely.

Profit-Sharing and Long-Term Agreements

Beyond licensing fees, royalties, and equity stakes, some collaborations include profit-sharing arrangements that extend well into the future. These agreements may involve the company committing to share a portion of its profits with the university, especially if the university’s ongoing research continues to enhance the commercialized product [20,26-28]. For example, the company might agree to share a percentage of net profits from the sale of products derived from the university’s technology. This profitsharing could be structured to ensure that as the company grows and becomes more profitable, the university’s financial returns also increase. This type of agreement often includes provisions for auditing and transparency, ensuring that both parties have a clear understanding of how profits are calculated and distributed. In some cases, the company might also commit to funding additional research or educational programs at the university, further strengthening the long-term partnership. These commitments could include sponsoring scholarships, funding new research centers, or supporting faculty positions related to the technology’s field [29]. This ongoing support helps maintain a strong relationship between the university and the company, fostering an environment of continuous innovation and shared success.

Sip, Stitch and Sustain: Difficulties in Patenting Sustainable Solutions

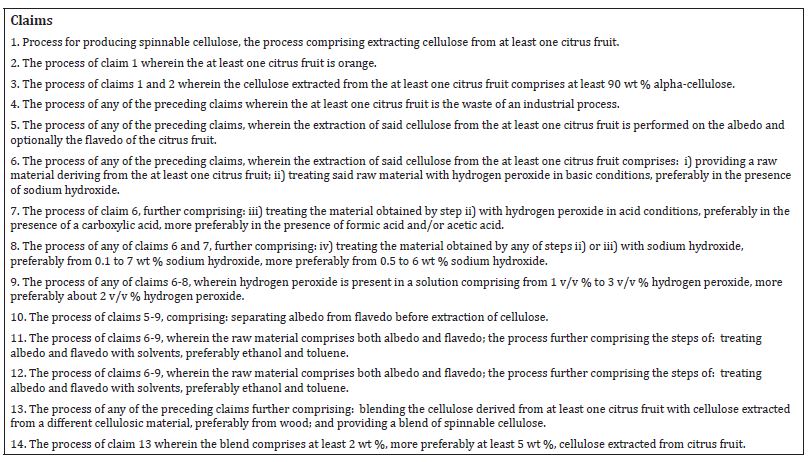

Patenting sustainable solutions, such as eco-friendly textiles like those developed by Orange Fiber, involves navigating a complex web of technical, legal, and ethical challenges [20,26-28,30]. The process of securing a patent in this context not only requires detailed technical documentation but also a deep understanding of multidisciplinary innovation and strategic management. In the case of Orange Fiber, the patented process for producing spinnable cellulose from citrus waste is an excellent example of how these challenges are met [30]. The company’s patent claims outline a series of specific steps that highlight the novelty and sustainability of the process. Below are the claims as outlined in their patent:

This section delves deeper into the intricacies of patenting such innovations, examining the interplay between multidisciplinary innovation, market dynamics, and strategic management.

Complexity of Innovation

The complexity of sustainable innovations like Orange Fiber’s citrus-derived textiles stems from the convergence of various scientific and engineering disciplines, each contributing to different stages of the product’s lifecycle. For example, the extraction of cellulose from citrus waste requires a deep understanding of biochemistry to break down the pectin and other components of citrus peels, a process distinct from typical plant-based cellulose extraction [31]. This step must then be integrated with chemical engineering processes to convert the cellulose into a usable fiber, a challenge that involves manipulating the molecular structure to ensure the fiber’s mechanical properties - such as tensile strength, elasticity, and durability - are suitable for textile production.

The patenting process for such a multidisciplinary innovation is not merely about protecting a novel idea but also about encapsulating the entire process in a legally defensible manner [30]. Companies must provide exhaustive technical documentation that not only describes each step of the process in detail but also explains how these steps interact. For example, Orange Fiber would need to detail the chemical reactions involved in the cellulose extraction, the machinery used for spinning the fiber, and the environmental conditions required for optimal production. Any oversight in this documentation could result in a weak patent that competitors could easily circumvent by tweaking certain process parameters, thereby achieving similar results without infringing on the patent. Moreover, the patent must be crafted in a way that anticipates potential challenges. For instance, if a competitor claims that the use of citrus waste for cellulose extraction is not novel, Orange Fiber would need to demonstrate not only that their specific method is unique but also that it offers superior results compared to existing methods. This could involve providing comparative data on the quality of the fibers produced, the efficiency of the process, and the environmental benefits, all of which add layers of complexity to the patenting process.

Prior Art and Novelty

Establishing the novelty of a sustainable innovation in a crowded market is a formidable challenge. The landscape of sustainable textiles is rapidly evolving, with numerous players— from startups to multinational corporations—developing new materials and processes [19,28]. In such a competitive environment, the line between innovation and incremental improvement can be blurry, making it difficult to demonstrate that a new process or material is genuinely novel and not just an obvious extension of existing technology. For example, while Orange Fiber’s innovation lies in using citrus waste to produce textiles, the broader concept of using agricultural by-products for textile production is not new. Competitors might be using pineapple leaves, banana fibers, or other plant-based materials, and these innovations could be cited as prior art during the patent examination process. To overcome this, Orange Fiber would need to present evidence that their process of extracting and processing cellulose from citrus waste is fundamentally different from, and superior to, these other methods. This might involve highlighting specific chemical pathways, the use of proprietary enzymes, or unique mechanical processes that differentiate their approach.

Additionally, Orange Fiber must navigate the global nature of patent law, where prior art from any country can impact the novelty of their invention [17]. This requires a comprehensive global search for similar technologies, which can be both time-consuming and costly. For example, an obscure academic paper published in a foreign language might describe a similar process, potentially jeopardizing the novelty of Orange Fiber’s patent. The company would need to engage in extensive legal and technical research, possibly hiring local experts in various countries to ensure that all potential prior art is identified and addressed in the patent application.

Ethical and Environmental Considerations

The ethical implications of patenting sustainable technologies add another layer of complexity to the decision-making process. While patents provide legal protection and a competitive advantage, they can also restrict access to environmentally beneficial technologies [22]. This tension is particularly acute in the context of global sustainability, where widespread adoption of green technologies is often more important than maximizing profits for any single company. For Orange Fiber, patenting their citrusderived textile technology could be seen as a double-edged sword. On one hand, securing a patent allows the company to control the use of its technology, ensuring that it is used in ways that align with their sustainability goals. This control could be vital in preventing misuse or degradation of the technology’s environmental benefits. For example, without patent protection, competitors might adopt a similar process but use cheaper, less sustainable methods that undermine the technology’s green credentials.

On the other hand, patenting the technology could limit its adoption, particularly in developing countries where textile manufacturers might not have the financial resources to pay for licensing fees. This could slow the global shift towards more sustainable textile production, counteracting the environmental benefits that Orange Fiber seeks to promote. The company must therefore consider alternative strategies, such as offering tiered licensing fees or open-source components of their technology, to balance their commercial interests with broader ethical considerations. From a strategic management perspective [28], Orange Fiber could adopt a hybrid approach to IP management [20,32]. They might patent the core elements of their technology to protect their competitive advantage while also licensing it under more flexible terms to encourage broader adoption. For example, they could implement a patent pool strategy, where multiple companies contribute patents to a shared pool that others can access under agreed-upon terms. This approach has been used successfully in industries such as telecommunications and could help Orange Fiber maximize the environmental impact of their innovation while still benefiting financially.

Cost and Resources

Securing a patent is a resource-intensive process that requires significant financial and managerial investment. The costs associated with patenting are not limited to the initial filing fees [22,28] but also include ongoing expenses such as legal fees, maintenance fees, and the costs associated with defending the patent against potential infringement [33]. For a small or mediumsized enterprise (SME) like Orange Fiber, these costs can be particularly burdensome. The initial patent application process alone can cost tens of thousands of dollars, with additional costs for filing in multiple jurisdictions. If Orange Fiber seeks global patent protection, they would need to file separate applications in each country or region where they wish to protect their innovation. This might involve translating the application into multiple languages, paying local filing fees, and hiring legal experts familiar with the patent laws of each jurisdiction.

Furthermore, maintaining a patent over its typical 20-year lifespan involves paying periodic maintenance fees [22], which can increase significantly over time. In some cases, the cumulative cost of maintaining a patent portfolio can exceed the initial investment in research and development. For example, a U.S. patent might require maintenance fees every 3.5 years, with costs increasing at each interval. For a company with multiple patents, these fees can quickly add up, straining financial resources that might otherwise be used for product development or market expansion. Defending a patent against infringement is another major cost consideration. In highly competitive markets, it is not uncommon for patents to be challenged by competitors seeking to invalidate them or design around them. Legal battles over patent rights can be lengthy and costly, often involving millions of dollars in legal fees and expert witness costs. For a company like Orange Fiber, which operates in the competitive and rapidly evolving fashion industry, the risk of patent litigation is significant. To mitigate this risk, the company might need to allocate substantial resources to building a robust legal team or partnering with a larger company that can provide legal support in exchange for a stake in the business or licensing rights.

Geographical Limitations

The territorial nature of patents means that protection is only granted in the countries where the patent is filed and approved. This creates a significant challenge for companies operating in global markets [28,30], as they must decide where to seek patent protection and how to allocate resources effectively. For Orange Fiber, the decision on where to file patents would involve a careful analysis of their target markets, manufacturing locations, and potential competitors. For example, the company might prioritize patent filings in major textile-producing countries such as China, India, and Bangladesh, as well as key consumer markets in Europe and North America [28]. Each of these regions presents different challenges in terms of patent law, enforcement, and market dynamics. In China, for instance, while the country has made significant strides in improving its IP enforcement in recent years, concerns about patent infringement and counterfeiting remain. Orange Fiber would need to assess whether the benefits of securing a patent in China outweigh the potential challenges of enforcement. Similarly, in the European Union, the company might need to navigate the complexities of the European Patent Convention (EPC), which allows for a unified patent application process but still requires validation in individual member states.

The cost of filing and maintaining patents in multiple jurisdictions can be prohibitively expensive, particularly for a growing company like Orange Fiber. To manage these costs, the company might adopt a phased approach to patent filing, focusing first on the most critical markets and then expanding to other regions as the business grows. This strategy would involve continuous market analysis and IP management, requiring a dedicated team to monitor global trends and adjust the company’s patent strategy accordingly.

To further bolster its IP strategy, Orange Fiber might also consider leveraging the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) process. The PCT allows the company to file a single international patent application that can later be used as the basis for seeking patent protection in multiple countries. By initially filing a PCT application, Orange Fiber can secure a priority date while delaying the high costs associated with filing in multiple jurisdictions. This approach gives the company additional time—typically up to 30 months from the initial filing date—to conduct market analysis, assess potential competitors, and determine which national or regional patents are most strategically valuable.

For example, after filing the PCT application, Orange Fiber could focus on key markets such as the United States, where patent US9771435B2 was eventually granted [22], and the European Union, where they have already secured protection through the EPO. The company might then evaluate additional filings in emerging markets or regions where textile manufacturing is prominent, such as Southeast Asia, while considering factors like local enforcement capabilities and the presence of potential infringers. This phased and strategic use of the PCT system allows Orange Fiber to manage costs effectively while maximizing the global reach and impact of its patent portfolio.

Balancing Innovation and Accessibility

The decision to patent a sustainable innovation like Orange Fiber’s textile technology involves a strategic trade-off between protecting intellectual property and promoting broader adoption of the technology. From a business strategy perspective, this decision impacts not only the company’s financial performance but also its brand reputation, market positioning, and contribution to global sustainability goals [32-34]. Brand’s management must consider whether the benefits of patent protection—such as exclusivity, potential licensing revenue, and market differentiation—justify the potential drawbacks, such as limiting access to the technology and slowing its adoption in markets that could benefit most from sustainable solutions [34]. For instance, if the company patents its technology and enforces it strictly, it might deter smaller textile producers from adopting the technology, particularly in emerging markets where the need for sustainable practices is greatest but financial resources are limited.

To balance these competing interests, a brand could explore alternative IP strategies that allow for both protection and accessibility. One option might be to implement a freemium model, where the basic version of the technology is made available for free or at a low cost, while premium features or additional services are offered for a fee. This approach could help the company establish a broad user base and promote sustainability while still generating revenue from more advanced or large-scale users. Another strategy could involve tiered licensing agreements, where different licensing terms are offered based on the licensee’s size, location, and intended use of the technology. For example, a brand can offer lower licensing fees or royalty rates to small or medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in developing countries, while charging higher fees to large multinational corporations [28]. This approach would allow the company to generate revenue from its technology while also supporting the broader adoption of sustainable practices. From a brand management perspective, these strategies can enhance brand’s reputation as a socially responsible company committed to global sustainability, potentially attracting customers, investors, and partners who value these principles. In an increasingly ecoconscious market, the ability to align business strategy with sustainability goals can be a significant competitive advantage, helping the company differentiate itself from competitors and build long-term brand loyalty.

Free Textiles: Innovation Without Patents

The landscape of sustainable textiles is characterized by a mix of patented innovations and non-patented developments, reflecting different strategic choices by companies and innovators. These examples illustrate how some modern sustainable textile innovations prioritize accessibility, collaboration, and brand development over securing patents, allowing for broader adoption and impact in the industry. Here are some examples of modern sustainable textiles that have not been patented:

a. Piñatex: Developed by Dr. Carmen Hijosa, Piñatex is a sustainable textile made from the fibers of pineapple leaves, a byproduct of the pineapple harvest. Instead of patenting the material, Dr. Hijosa chose to focus on branding and collaboration with ethical fashion brands. This decision has allowed the material to be widely adopted without the barriers that a patent might impose, helping to spread its use as a sustainable alternative to leather.

b. Mycelium Leather: Mycelium-based materials, made from the root structure of mushrooms, have gained popularity as a sustainable alternative to traditional leather. Several companies, like MycoWorks and Bolt Threads, have developed proprietary processes, but there are also open-source versions of mycelium leather production that are not patented. This openness has fostered a collaborative environment, encouraging broader experimentation and adoption in the fashion industry.

c. Recycled Polyester (rPET): While the technology for recycling PET (polyethylene terephthalate) into fibers is wellestablished, many brands have opted not to patent their specific processes for creating recycled polyester textiles. Instead, they focus on sustainability certifications and brand loyalty. This approach has made rPET a widely used material in sustainable fashion, with companies like Patagonia promoting its use through their environmental advocacy rather than through exclusive patent rights.

d. Tencel (Lyocell): Although the original lyocell production process is patented by Lenzing AG under the brand name Tencel, there are non-patented versions of similar sustainable cellulose-based textiles being developed. Some smaller producers focus on creating lyocell-like materials without patenting the process, emphasizing environmentally friendly practices and transparency over IP protection.

This section explores the reasons behind the lack of patents for many sustainable textiles, drawing on other business strategies and market dynamics.

Open-Source and Collective/Collaborative Ingenuity

In the area of sustainable textiles, open-source and collaborative development approaches are increasingly common, driven by the recognition that environmental challenges require collective action [28]. Many companies and organizations in this space prioritize the dissemination of their innovations over the exclusivity provided by patents, choosing to share their knowledge and technology freely to maximize their environmental impact. For example, the Fashion for Good initiative, a global platform for sustainable fashion innovation, encourages collaboration among brands, manufacturers, and startups to develop and scale sustainable technologies. Companies participating in this initiative often choose not to patent their innovations, instead focusing on creating industry-wide standards and best practices that can be adopted by all players. This open approach can accelerate the adoption of sustainable practices across the industry, as it removes the barriers associated with licensing fees and patent restrictions. One notable example is the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s Circular Fibres Initiative, which promotes the development of circular textile economies where materials are reused, recycled, and kept in circulation for as long as possible. Participants in this initiative, including major brands like H&M and Nike, share their research and development efforts openly, recognizing that the scale of environmental challenges requires industry-wide solutions rather than isolated innovations protected by patents. From a strategic management perspective, companies that engage in open-source development often rely on alternative business models to generate value [32-34]. For instance, they might focus on providing consulting services, training, or certification programs based on their innovations. By positioning themselves as thought leaders in sustainability, these companies can build strong brand reputations and foster customer loyalty, even without the exclusive rights conferred by patents.

Wisdom of the Ages: Traditional and Indigenous Knowledge

Many sustainable textile innovations are rooted in traditional and indigenous knowledge, which has been developed and refined over centuries [35,36]. These practices, often involving natural materials and processes, are typically considered part of the cultural heritage of the communities that developed them and are not patented [28,33]. Instead, they are passed down through generations and shared openly within and between communities. For example, the use of handwoven textiles dyed with natural indigo in India, known as “Khadi”, represents a sustainable practice that has been preserved and promoted as a symbol of India’s cultural and economic independence. The Khadi movement, popularized by Mahatma Gandhi, emphasizes the use of locally sourced materials and traditional hand-spinning techniques as a means of promoting self-reliance and sustainability. While these techniques could potentially be patented, doing so would conflict with the cultural and ethical values that underpin the movement.

The Pacific Islands and parts of Africa have a rich tradition of creating bark cloth from the inner bark of trees like the mulberry or fig [36-40]. This process, which involves soaking, pounding, and stretching the bark into sheets, is an early example of how natural fibers can be transformed into usable textiles. Similarly, in Southeast Asia and the Philippines [41-43], communities have historically crafted textiles from banana fibers and pineapple leaves. The production of Piña fabric from pineapple leaves [44] and Abacá [45] from banana fibers involves harvesting plant byproducts and processing them into strong, sustainable fabrics. These practices are not only sustainable but have also influenced modern innovations in sustainable fashion, such as the creation of fruit-based textiles like those made by Orange Fiber. The use of plant fibers, whether from trees, bananas, or pineapples, reflects a deep understanding of the natural environment and highlights how traditional methods can inform and inspire contemporary efforts to create eco-friendly textiles.

In the global context, indigenous communities in Latin America, Africa, and Asia have long used sustainable practices in textile production, such as the use of organic cotton, natural dyes, and hand-weaving techniques. These practices are often seen as communal knowledge, and efforts to patent them by outsiders have sparked controversy, as in the case of attempts to patent traditional Andean textile patterns. Such actions are viewed as a form of “biopiracy” [46], where corporations or individuals seek to profit from traditional knowledge without proper acknowledgment or compensation to the originating communities.

From a business strategy perspective, companies that incorporate traditional and indigenous knowledge into their products [47] often emphasize authenticity, cultural heritage, and ethical sourcing as key components of their brand identity. For instance, brands like Patagonia and Indigenous Designs highlight their partnerships with indigenous communities and their commitment to fair trade practices, using these values as a selling point to attract environmentally and socially conscious consumers. These connections underscore the importance of integrating indigenous knowledge into modern sustainable practices, demonstrating that innovation in textile production often builds on the wisdom of ancient, resource-efficient techniques.

Small-Scale or Local Production

Small-scale producers and local artisans play a crucial role in the sustainable textile industry, often creating high-quality, environmentally friendly products using traditional methods. These producers may not pursue patent protection for various reasons, including a lack of resources, knowledge, or interest in the formal IP system [28,33,34]. Instead, they rely on the uniqueness of their craftsmanship and the quality of their products to compete in the market. For example, small cooperatives in Southeast Asia and Africa produce textiles using organic cotton and natural dyes, often employing traditional weaving techniques passed down through generations. These products are marketed as premium, artisanal goods, with a focus on quality, sustainability, and cultural heritage. While these innovations could be patented, the producers often choose not to do so, either because they view the techniques as communal knowledge or because the costs and complexity of the patenting process are prohibitive. From a strategic management perspective [34], small-scale producers often focus on niche markets where consumers are willing to pay a premium for ethically produced, sustainable goods. These producers might also engage in direct-to-consumer sales through online platforms, bypassing intermediaries and maximizing their profits. By building strong relationships with their customers and emphasizing the story behind their products, these artisans can create a loyal customer base that values the authenticity and sustainability of their offerings.

Focus on Brand Identity Rather Than Patent Protection

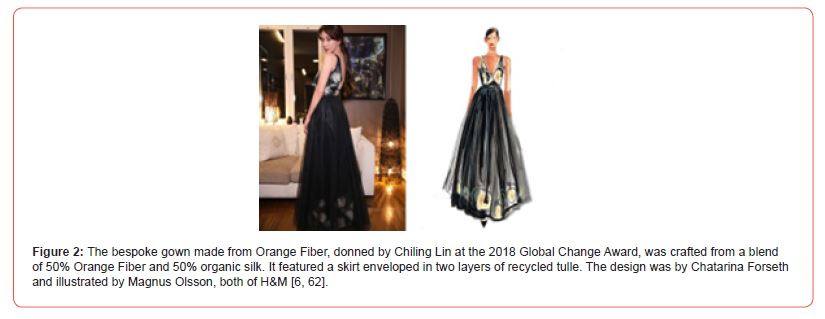

In the sustainable textile industry, some companies prioritize building a strong brand identity over securing patents for their innovations. By focusing on branding, these companies create a distinctive image and reputation that differentiates their products in the market, reducing the need for legal protections like patents. A prime example of this approach is Stella McCartney, a luxury fashion brand known for its commitment to sustainability and ethical practices [48]. While the brand has developed innovative materials and processes, such as vegetarian leather and recycled textiles, it has not focused heavily on patenting these innovations. Instead, Stella McCartney has built a strong brand identity around sustainability, positioning itself as a leader in eco-friendly fashion. The brand’s success relies on its ability to communicate its values and commitments to consumers, who are willing to pay a premium for products that align with their ethical beliefs (Figures 1 & 2).

Another example is Patagonia, a company that has built its brand around environmental activism and sustainability [49]. Patagonia’s approach to IP is unique in that the company often shares its innovations with competitors to promote sustainability across the industry. For instance, Patagonia publicly released its proprietary clean wool standards, encouraging other companies to adopt more sustainable practices. This strategy reinforces Patagonia’s brand as a leader in environmental responsibility while fostering goodwill and customer loyalty. From a strategic management perspective, companies that focus on brand identity over patents often invest heavily in marketing, public relations, and customer engagement. They use storytelling, transparency, and social responsibility as key components of their brand strategy, creating a strong emotional connection with their customers. This approach can be particularly effective in the sustainability sector, where consumers are increasingly looking for brands that align with their values.

Strategic Pathways: Business and IP Beyond Patents

When sustainable innovations are not patented, companies and inventors can employ a variety of alternative strategies to protect their intellectual property, maintain a competitive advantage, and ensure the long-term success of their business. This section explores these strategies in detail, drawing on business theory, realworld examples, and strategic management principles.

Trade Secrets

In the realm of intellectual property, trade secrets represent a powerful and often underutilized method for protecting innovations that a company chooses not to patent [50]. Unlike patents, which require public disclosure of an invention’s details in exchange for legal protection, trade secrets involve keeping crucial information about a product, process, or method entirely confidential [51]. This secrecy can cover a wide range of sensitive details, from manufacturing techniques and chemical formulations to proprietary software algorithms and customer lists. The legendary example of Coca-Cola’s formula highlights the effectiveness of this approach, where the recipe is safeguarded through a combination of stringent internal security protocols, restricted access, and legal agreements with suppliers, bottlers, and employees to ensure that the exact formula remains undisclosed for over a century [52,51].

For Orange Fiber, leveraging trade secrets could be particularly advantageous in protecting the intricate details of their citrus waste conversion process—a core element of their competitive advantage in the sustainable textile industry. The specifics of how they extract cellulose from citrus byproducts, refine it into spinnable fibers, and produce high-quality textiles are crucial to maintaining their market differentiation. By keeping these elements under wraps, Orange Fiber can prevent competitors from duplicating their methods without the need for a patent, which would require full disclosure of their process. To effectively implement trade secret protection, Orange Fiber would need to establish a multi-layered security framework. This could involve physically securing facilities where sensitive processes are conducted, such as limiting access to certain areas of their production plants to only those employees directly involved in the process. Advanced digital security measures would also be crucial, including the use of encrypted data storage for all technical documentation, process specifications, and proprietary software used in the production process. Additionally, Orange Fiber should enforce stringent non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) not just with employees, but also with any external partners, contractors, or suppliers who might gain access to sensitive information. These NDAs would need to be meticulously drafted to cover all potential scenarios of information leakage and include severe penalties for breaches.

Moreover, it’s essential for Orange Fiber to recognize that while trade secrets provide indefinite protection, they come with inherent risks. The primary risk is that trade secrets do not offer legal recourse if the information is independently discovered by a competitor, or if an employee or partner leaks the information, either intentionally or unintentionally [51]. Therefore, Orange Fiber must adopt a proactive approach to manage these risks. This includes regular audits of security measures, continuous monitoring of digital systems for potential breaches, and updating NDAs as the business expands or as new partnerships are formed. From a strategic business perspective, relying on trade secrets requires a company to focus intensively on continuous innovation and R&D [50,52]. The market is dynamic, and competitors are constantly evolving their strategies to gain an edge. By frequently enhancing their processes, introducing new technologies, and refining their methods, Orange Fiber can stay ahead of competitors who might attempt to reverse-engineer their products. This proactive innovation approach involves not only internal R&D efforts but also scouting for new technological advancements and potential collaborations with research institutions or other industry players to maintain their technological lead.

Trademarks and Branding

Orange Fiber deploys a comprehensive trademark strategy, reflecting their ambition to lead in the sustainable fashion industry. Orange Fiber has secured trademark protection in multiple jurisdictions, covering a variety of Nice classes that are critical to their operations. The Nice Classification is an international system used to categorize goods and services for the purposes of trademark registration, and Orange Fiber’s trademarks primarily fall within classes relevant to textiles and related materials [53].

a. International Trademark: The company holds an international trademark with protections extending to countries including the Russian Federation, Singapore, India, Japan, Korea (Republic of), China, Mexico, Ukraine, and the USA. This international registration is in force, covering Nice Class 24.

b. Singapore: Orange Fiber’s trademark was registered in Singapore on September 7, 2017, under the registration number 40201704385V in Nice Class 24, which covers textiles and textile goods.

c. Brazil: In Brazil, Orange Fiber registered their trademark on June 23, 2020, under registration number 911940405, also in Nice Class 24.

d. Italy: The trademark was first registered in Italy on October 28, 2015, under registration number 0001651954, covering Nice Classes 22, 23, and 24. These classes encompass fibers, yarns, and various textile goods, indicating a broad scope of protection within the country of origin.

e. United Kingdom: In the UK, Orange Fiber’s trademark was registered on March 30, 2015, under registration number UK00913452537. This trademark covers Nice Classes 1, 17, 22, 23, and 24, indicating an even broader scope that includes raw materials, chemicals used in industry, and textile fibers.

f. European Union: The company has also secured regional trademark protection in the European Union, with the trademark registered on March 30, 2015, under registration number 013452537. This registration covers Nice Classes 1, 17, 22, 23, and 24, similar to the UK registration, providing extensive protection across the EU member states.

g. United States: In the United States, the trademark was registered on March 6, 2018, under registration number 5415054, specifically in Nice Class 24.

h. Canada: A trademark application was filed by Riccardo Ciullo in Canada under registration number 1817984 covering Nice Classes 22 and 24, but this application has since ended, indicating that Orange Fiber may need to revisit its strategy in this jurisdiction.

The comprehensive trademark strategy employed by Orange Fiber reflects a deliberate approach to securing its brand and innovation on a global scale. By registering trademarks in key markets across Europe, North America, Asia, and Latin America, Orange Fiber ensures that its brand is protected in regions with significant textile production capabilities and consumer markets. The focus on Nice Class 24 (textiles and textile goods) across multiple jurisdictions highlights the company’s commitment to protecting its core products. Additionally, the inclusion of broader categories in the UK and EU registrations, such as Nice Classes 1 (chemicals) and 17 (rubber, gutta-percha, gum, asbestos, mica), suggests that Orange Fiber is positioning itself to protect not just the finished textile products but also the raw materials and intermediate goods involved in their production. This could provide a competitive advantage by safeguarding all stages of their innovative process. The strategic decision to hold international trademark protections [54,55] through the Madrid System—covering diverse markets such as the USA, China, and India—demonstrates Orange Fiber’s intention to secure its position in both established and emerging markets. This broad geographical coverage also suggests a proactive approach to mitigating the risk of counterfeiting and unauthorized use of their brand in regions known for intellectual property challenges.

However, the lapse in the Canadian trademark application indicates a potential gap in their global strategy that may need to be addressed, particularly if Canada becomes a more significant market for their products in the future.

In conclusion, Orange Fiber’s extensive and well-thought-out trademark portfolio is a testament to their strategic foresight in protecting their brand and innovation across critical global markets. This robust trademark protection not only secures their position in the competitive sustainable textile industry but also enhances their brand’s credibility and value as they expand their global footprint.

First-Mover Advantage

First-mover advantage is a strategic concept that refers to the competitive benefits gained by being the first to enter a new market or introduce a new product [56,57]. In the case of sustainable innovations, being the first to market can allow a company to establish itself as a leader in the field, build brand recognition, and capture market share before competitors have a chance to respond. This early entry into the market provided several strategic advantages, including the ability to set the standards for the industry. As pioneers, Orange Fiber could dictate the terms of market engagement, set pricing benchmarks, and influence consumer perceptions of sustainable luxury. The company’s ability to forge early partnerships with high-profile fashion brands further solidified its market presence and credibility. However, the firstmover position also demanded substantial upfront investment in R&D, aggressive marketing to educate consumers, and rapid scaling of production capabilities [56]. These efforts are necessary to capitalize on the initial market lead and to create significant entry barriers for competitors. Additionally, first movers must be prepared for competitors to learn from the first mover’s successes and failures and potentially offer improved or lower-cost alternatives [58]. To sustain their first-mover advantage, Orange Fiber could focus on continuous innovation, regularly introducing new products, improving their existing offerings, and expanding their market presence. By maintaining their leadership position, they can create barriers to entry for competitors and continue to dominate the sustainable textile market [56-59].

Partnerships and Licensing

Strategic partnerships and licensing agreements are vital mechanisms for companies like Orange Fiber to extend their technological reach while safeguarding intellectual property. By licensing their citrus waste conversion technology to select textile manufacturers, Orange Fiber can monetize its innovation through royalties, while maintaining stringent control over how and where the technology is deployed [60]. This method enables rapid market penetration across multiple regions, scaling the impact of their innovation far beyond what internal production capabilities could achieve [60]. Licensing also mitigates the financial risks associated with direct market entry by transferring the burden of production and market adaptation to local manufacturers. For instance, by licensing their technology [61] to manufacturers in key textileproducing countries like China or India, Orange Fiber can capture market share without the capital investment and operational complexities of establishing their own production facilities in these regions.

The receipt of the Global Change Award was instrumental for Orange Fiber in advancing their research and development efforts, culminating in a pilot production run that yielded over 10,000 meters of fabric. This fabric was exclusively procured by Salvatore Ferragamo, who utilized it to introduce their pioneering Ferragamo Orange Fiber Collection. At the 2017 Green Carpet Fashion Awards Italia, Salvatore Ferragamo showcased several exclusive items crafted from this innovative material, including an evening dress, a handbag from the Museo Salvatore Ferragamo collection, and “F” wedge sandals, notably adorned by the renowned model Karolina Kurkova.

Conclusions

This study underscores the transformative potential of sustainability within the luxury and premium fashion sectors, introducing the concept of "populuxury" as a framework for understanding this evolution. By bridging luxury with environmental consciousness, brands like Orange Fiber demonstrate how innovation and strategic intellectual property (IP) management can redefine the landscape of fashion consumption.

Key takeaways:

a. Integration of Sustainability and Luxury:

The research highlights a paradigm shift where luxury brands incorporate sustainable practices, not as a niche effort but as a central pillar of their identity. This alignment satisfies evolving consumer preferences for ethical and environmentally conscious products while maintaining exclusivity and premium appeal.

b. Strategic Intellectual Property Management:

Companies leveraging IP strategies, such as patents, trademarks, and trade secrets, are not only protecting their sustainable innovations but also establishing leadership within the industry. Orange Fiber’s practices exemplify how IP serves as both a defensive tool and a market differentiator.

c. Redefining Consumer Expectations:

The fusion of sustainability and luxury is reshaping consumer expectations, compelling brands to balance ecological responsibility with high-quality, aspirational products. This shift is fostering a more informed and environmentally aware luxury clientele.

d. Industry Benchmarking and Academic Implications:

The emergence of "populuxury" sets new standards for sustainability in luxury fashion, encouraging broader industry adoption of eco-friendly practices. Academically, this concept offers a novel lens to analyze sustainable consumption trends and the role of IP in fostering innovation within high-end markets.

e. Practical Applications:

The findings offer actionable insights for fashion brands aiming Citation: Marlena Jankowska*, José Geraldo Romanello Bueno and Mirosław Pawełczyk. What’s in an Orange? Squeezing Value Page 14 of 15 from Agricultural Waste into Sustainable Populuxury Fashion and IP Strategy. to integrate sustainability with luxury, emphasizing the importance of innovation, IP management, and alignment with consumer values to achieve competitive advantage.

In conclusion, “populuxury” represents a meaningful intersection of sustainability and luxury, redefining industry norms and consumer behavior. This study lays the groundwork for further exploration into how intellectual property can drive sustainable innovation, inspiring future research and guiding practical applications within the fashion sector.

Acknowledgment

This research was funded in whole by the National Science Centre in Poland, grant “Brand Abuse: Brand as a New Personal Interest under the Polish Civil Code against an EU and US Backdrop”, grant holder: Marlena Maria Jankowska-Augustyn, number: 2021/43/B/HS5/01156. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC-BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript (AAM) version arising from this submission.

References

- McNeil P, Riello G (2016) Luxury: A rich history. Oxford University Press, UK.

- Seyed T (2019) Technology Meets Fashion: Exploring Wearables, Fashion Tech and Haute Tech Couture. In Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems pp. 1-5.

- Casciani D, D Itria E (2024) Fostering Directions for Digital Technology Adoption in Sustainable and Circular Fashion: Toward the Circular Fashion-Tech Lab. Systems 12(6): 190-223.

- Bolzan P, Regaglia A (2022) Fashion-tech and growing materials: challenges and opportunities facing bacterial cellulose. Future of fashion-tech alliance pp. 24-34.

- Horvath J, Hoge L, Cameron R, Horvath J, Hoge L, et al. (2016) Fashion Tech. Practical Fashion Tech: Wearable Technologies for Costuming, Cosplay, and Everyday pp. 3-12.

- (2019) H&M. Orange Fiber. Retrieved from H&M Foundation.

- PANGAIA (n.d.). FLWRDWN™ + FLWRFILL™.

- Amed I, Balchandani, A, Beltrami M, Berg A, Hedrich S, et al. (2021) The state of fashion 2022. McKinsey & Company, United States.

- (2018) Accenture. Circular x fashion tech: Trend report 2018.

- Amed I, Berg A, Balchandani A, Hedrich S, Rölkens F, et al. (2020) The state of fashion 2020: Navigating uncertainty. McKinsey & Company, United States.

- Bell A (2020) Future consumer. WGSN. https://createtomorrowwgsn.com/1927340/14/.

- Jones A (2023) Stella McCartney awarded CBE for her sustainable fashion work. Species Unite, NY.

- Bennie F, Gazibara I, Murray V (2018) Fashion futures 2025: Global scenarios for a sustainable fashion industry. Forum for the Future: Action for a Sustainable World. Levi Strauss & Co.

- Jung S, Jin B (2014) A theoretical investigation of slow fashion: sustainable future of the apparel industry. International journal of consumer studies 38(5): 510-519.

- Jankowska M, Pawełczyk M, Kania J (2023) A fashion brand caught in the crossfire: A tale of the US fashion act, sustainability, consumer trends and their legal implications. Przegląd Ustawodawstwa Gospodarczego 4(1): 19-26.

- Wood J (2019) Bioinspiration in Fashion-A Review. Biomimetics (Basel, Switzerland) 4(1): 16-20.

- Aishwariya S (2020) Textiles from orange peel waste. Science & Technology Development Journal 23(2): 508-516.

- (2020) H&M Foundation. (n.d.). Global Change Award - reinventing fashion.

- Capitani G, Comazzetto G (2021) The concept of sustainable development in global law: Problems and perspectives. Athens Journal of Law 5(1): 35-46.

- Anguelov N (2021) The sustainable fashion quest: innovations in business and policy. Productivity Press.

- Liu Y, Shi J, Langrish TAG (2006) Water-based extraction of pectin from flavedo and albedo of orange peels. Chemical Engineering Journal 120(3): 203-209.

- Santanocito AM, Vismara E (2015) Production of textile from citrus fruit (WO2015018711A1) [Patent]. World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

- Mat Zain NF (2014) Preparation and characterization of cellulose and nanocellulose from pomelo (Citrus grandis) albedo. Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences 05(01): 2-4.

- Sachidhanandham A (2020) Textiles from orange peel waste. Science and Technology Development Journal 23(2): 508-516.

- Kieckens E (2021) Citrus fabric gives fashion industry a vitamin boost. Innovation Origins.

- Todeschini BV, Cortimiglia MN, Callegaro-de-Menezes D, Ghezzi A (2017) Innovative and sustainable business models in the fashion industry: Entrepreneurial drivers, opportunities, and challenges. Business horizons 60(6): 759-770.

- Witzburg FM (2021) Fashion Forward: Fashion Innovation in the Era of Disruption. Cardozo Arts & Ent LJ 39(2): 705-734.

- Van Santen S (2023) Changing the Fast Fashion Paradigm: The Role of Intellectual Property and Sustainable Entrepreneurship. SSRN pp.1-37.

- Weinswig D (2017) Fast fashion speeding toward ultrafast fashion. Fung Global Retail & Technology.

- Ranka S, Raj S, Sikchi P (2023) RELEVANCE OF PATENTS IN THE GROWING FASHION INDUSTRY. Russian Law Journal 11(1S): 99-107.

- Pal H, Sonia RS Futuristic Trends for Sustainable Fashion: Innovations in Material, Technology and Concepts. Fashion & Textile Industry 4.0-Opportunities & Challenges for Education 4.0, 41.

- Henninger CE, Niinimäki K, Blazquez M, Jones C (2022) Sustainable fashion management. Routledge.

- Charter M, Pan B, Black S (Eds.). (2023) Accelerating sustainability in fashion, clothing and textiles. Routledge.

- Weiss C, Trevenen A, White T (2014) The branding of sustainable fashion. Fashion, Style & Popular Culture 1(2): 231-258.

- Ling TC, Inta A, Armstrong KE, Little DP, Tiansawat P, et al. (2022) Traditional knowledge of textile dyeing plants: A case study in the chin ethnic group of western Myanmar. Diversity 14(12): 1065-1075.

- Junsongduang A, Sirithip K, Inta A, Nachai R, Onputtha B, et al. (2017) Diversity and traditional knowledge of textile dyeing plants in northeastern Thailand. Economic Botany 71(1): 241-255.

- Chantamool A, Suttisa C, Gatewongsa T, Jansaeng A, Rawarin N, et al. (2023) Promoting traditional ikat textiles: ethnographic perspectives on indigenous knowledge, cultural heritage preservation and ethnic identity. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication pp. 1-20.

- Sharrad P (2020) Fabricating Identity: Textiles in the Pacific. A Companion to Textile Culture pp. 187-200.

- Addo PA (2017) Geographies of textile authenticity: Marking Tongan temporal and social relationships in diasporic cultural production. Pacific Studies 40(1-2): 18-30.

- Kuchler S, Were G (2014) The art of clothing: a Pacific experience. Routledge.

- Ho CM (2005) Biopiracy and beyond: a consideration of socio-cultural conflicts with global patent policies. U. Mich. JL Reform 39(3): 433-542.

- Maxwell R (2012) Textiles of Southeast Asia: Trade, tradition and transformation. Tuttle Publishing, Vermont, US State.

- Novellino D (2006) Weaving traditions from Island Southeast Asia: Historical context and ethnobotanical knowledge. In IVth International Congress of Etnobotanical (ICEB 2005). Ethnobotany: At the Junction of the Continents and the Disciplines. Istanbul, Turkey pp. 307-316.

- Montgomery M (2017) Traditional Textile Revival: Demonstrating the Potential of Piña Fabric for Apparel. Master's thesis, Oklahoma State University, United States.