Research Article

Research Article

Sustainability Transitions in Disclosures in the Fashion Industry: Comparative Insights into Social Sustainability, Circularity and Systemic Shifts

Marlen Gabriele Arnold* and Katja Beyer

Chemnitz University of Technology, Germany

Marlen Gabriele Arnold, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Corporate Environmental Management and Sustainability, Chemnitz University of Technology, Thüringer Weg 7, Chemnitz 09126, Germany.

Received Date: April 24, 2020; Published Date: May 28, 2020

Abstract

The fashion industry is the second largest global industry and constantly involved in local, regional and global affairs including environmental harm and social abuse. Stakeholder engagement, rising public consciousness and responsibility as well as economic pressure and entrepreneurial creativity have been resulted in nascent social and circular business strategies in the fashion industry as well as evolutionary steps towards sustainability in general. By respecting planetary boundaries circular economy is one approach the fashion industry is also facing at. Although circular economy is associated with benefits for society, social sustainability-related issues are not automatically addressed and integrated. But how are ideas and approaches mirroring social sustainability, circular strategies and systemic shifts embedded in the fashion industry? Conducting a software-based content analysis by means of LeximancerTM, social sustainability concepts in the fashion industry were compared for three groups at three different times. Therefore, academic publications, two large and internationally operating fashion companies, and stakeholder communication concerning sustainable and circular fashion were investigated. The findings reveal that social issues are underrepresented in the concept of circular economy in the fashion industry and limited to standard topics. Systemic shifts are mainly addressed by academia and stakeholders. We strongly recommend to integrate social sustainability concepts from the very first into approaches of circular economy in order to strengthen a sustainable development in the fashion industry.

Keywords: Social sustainability; Sustainability transitions; Circular economy; Fashion industry; Stakeholder; Software-based content analysis; LeximancerTM

Introduction

Sustainability in the global textile, apparel and fashion industry is becoming more and more important. This industry, characterized by long, complex and global value chains, and embracing a wide range of stakeholders and interest groups, is confronted with multiple sustainability challenges due to prevalent linear production and consumption patterns. Next to environmental impacts such as water pollution, chemicals, waste accumulation or rainforest destruction [1,2], the industry is also responsible for social harm and crises across the world including human rights abuses, child labour or worker discrimination [3].

The recent Covid-19 global pandemic illustrates the still-existing deficits and paradoxes, multi-faceted and intricate sustainability challenges in the industry in an impressive way. The unprecedented outbreak of the pandemic has led to the cancellation of orders in Asia by some of the largest fashion companies in Western countries, thereby leaving garment workers in factories located in countries such as Bangladesh or Cambodia unpaid and weakened in their working and living conditions [4,5]. The temporary closure of retail shops and consumer shutdown in particularly western textile consumption hubs is creating enormous economic and financial difficulties involving lower income and short-time working for employees, while retailers continue to encourage online shopping [6]. At the same time, the sustained outsourcing of parts of textile production to low-cost production countries now being deemed as essentially relevant such as medical face masks and components or provision of fabrics illustrates the dependence of entire (primarily western) societies on stable global value chains, commodity flows, transport and logistics networks, and, of course, mutual goodwill. However, the pandemic also offers opportunities for reorientation and change towards greater social sustainability, awareness and respect for the ecological foundations of society. Terms closely linked to social sustainability such as solidarity, cohesion, responsibility, cooperation (instead of competition), commitment, localism, integrity and transparency take on special meaning in these times and promote new movements such as #FairFashionSolidarity. They, however, also require joint and ‘true’ sustainability solutions on a global scale.

Social sustainability is concerned with managerial strategies and processes concerning positive and negative impacts of corporate activities on people and communities [7]. Müller-Christ G [8] differentiates different dimensions of social sustainability embracing opportunities for shaping and promoting living spaces that enable decision-making, responsibility and action based on reciprocal rather than asymmetrical relationships. With regard to the global textile, apparel and fashion industry, particularly the collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh in 2013 forged the implementation of social sustainability and compliance [9-11]. This implies also calls for systemic and radical changes concerning prevailing production and consumption patterns requiring also non-technological innovations [12-14]. One way of fostering such shifts and transitions towards sustainability is represented by the circular economy concept [15]. But how are ideas and approaches mirroring social sustainability, circular strategies and systemic shifts embedded in the fashion industry?

Against this background, based on a multiple-pillar conceptual framework, this research addresses the following research questions:

• RQ 1: What concepts assigned to social sustainability, circular strategies and systemic shifts are covered in the sustainability reports of fashion companies?

• RQ 2: How do these aspects deviate from disclosures in academia and broader society?

Firstly, an overview of the circular economy as a core concept for driving sustainability and sustainable development will be presented. It is followed by the description of material collection and data analysis employed in the present study. We then illustrate and discuss the findings of our software-based content analysis by highlighting particularly concepts mirroring social sustainability and concepts indicating change, shifts and transitions as communicated by different actors closely linked with the textile, apparel and fashion industry.

Sustainability Transitions towards the Circular Economy

This section summarizes conceptual and theoretical foundations related to the concept of circular economy as well as sustainable and circular business models. Against the background of the study’s research questions, particular attention has been given to highlighting aspects concerning social sustainability in circular strategies as emphasized in extant literature.

“Sustainability transitions are long-term, multi-dimensional, and fundamental transformation processes through which established socio-technical systems shift to more sustainable modes of production and consumption” [16]. The move towards a circular economy can be considered to spur such transition processes. It is aimed at a paradigm shift towards innovative and other paths of economic interaction, productions systems, consumption behavior and habits, and business models refocusing from mainly linear practices, like exploit-make-take-waste, to a regenerative, circular and green economy [17-19]. Several issues are particularly emphasized, such as closing loops, reduction of resource consumption, decoupling of wealth from ecosystem harm, cradle-to-cradle and investing in social and ecological longterm resilience [20-22]. So, respecting ecosystem capacities and planetary boundaries by reorganizing economic activities towards a reuse, repair, remanufacture and recycling of goods and services are key objectives in a circular economy. Shifting towards a circular economy aims at systemic redesign, organizational and institutional changes resulting in sustainability profits [20,23-25,15]. Although it is a promising concept vital criticism is found. Currently, practical implementation is critical as well as a lack of industry-specific solutions and specifications [23,18,25,26]. Consequently, clarifying and guiding research is necessary.

Especially in light of the criticism of being too vague there are several parallels between the concepts of circular economy and sustainability / sustainable development. Both stress intraand intergenerational aspects, an integration of criteria that goes beyond economic factors for change and the entrepreneurial responsibility for transitions [21,27-29]. Main differences are to be found concerning key objectives, criteria, methods and impacts. Circular economy mainly focuses on ecological and economic harmonization whereas sustainability also integrates social issues by integrating and harmonizing social, environmental and economic concerns as well as broad stakeholder interests [30]. In circular economy concepts social aspects often are of inferior significance being considered only indirectly [31,22]. This has already been criticized in the scientific community [32]. Indeed, potentials for incorporating social sustainability include value-based changes of the overall global economic system as well as the establishment of new ways of non-ownership, low consumption, decent work, etc., and may enable creating new value [32-34].

Transforming value chains, business models as well as business models innovations are a pivotal goal for a circular economy in the fashion industry and are demanded by several stakeholders [35- 37]. Although particular issues related to social sustainability are addressed, e.g. sustainable consumption, sufficiency or system change, circular strategies do not embrace all pillars of sustainability. As social sustainability concepts are underrepresented in circular economy approaches, this study will analyse and contrast socialrelated concepts in the fashion industry from a multi-stakeholder perspective.

Method

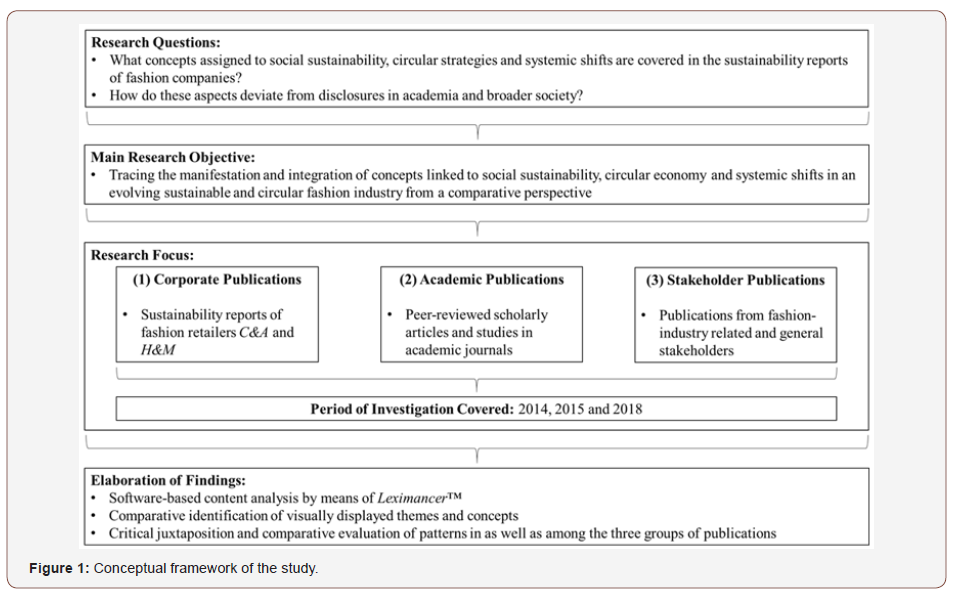

Our study builds on a multiple-pillar conceptual framework and analyses three different groups of publications from a comparative perspective. These disclosures include corporate sustainability reports of two fashion retailers, academic publications, as well as reports and documents issued by stakeholders. Thereby, the study covers not only practical and theoretical perspectives, but also discourses in the broader public. The following section describes the process of identifying, collecting and evaluating relevant material as well as the method of data analysis chosen. Figure 1 presents the overall analytical and conceptual framework of our research.

Material collection

The first group of publications involves corporate sustainability reports since they are acknowledged and extensively used in corporate disclosure [38]. They provide information on sustainability-related themes including issues, measures and projects concerning social and environmental sustainability as well as strategies relating to circular economy. In the present research, focus is made on corporate sustainability reports of the two European-based fashion retailers C&A and H&M. Given differences in corporate sustainability disclosure practices, we included only reports available and downloadable across both companies in the final analysis. In total, 9 corporate sustainability reports between 2014 and 2018 was collected from each of the companies’ sustainability websites. These include 4 reports of C&A as well as 5 reports issued by H&M. The results presented below reflect the analysis of the sustainability reports of each company in 2014, 2015 and 2018. Eventually, both companies were selected for the following four reasons.

1. Economic scope of activity: Both C&A as well as H&M are two of the top-ten European fashion brands. C&A, a Dutch brand with headquarters in Belgium and Germany, operates internationally employing 51,000 people across 21 countries. The company has around 1,900 stores [39]. The H&M Group, based in Stockholm (Sweden), is the 2nd largest fashion retailer across the world with about 177,000 employees and around 4,900 stores in 72 markets (H&M 2019) [40].

2. Efforts concerning the integration of sustainability measures and circular economy: Both companies have repeatedly been communicating about their efforts to foster the implementation of sustainability and circular concepts in the fashion industry. Exemplarily, C&A has been pioneering product innovations with regard to the concept of cradle-tocradle. According to the company’s 2018 sustainability report around 4 million pieces of cradle-to-cradle certifiedTM apparel have been marketed. Moreover, by 2020, the company seeks to source 100% certified organic cotton or Better Cotton (C&A Global Sustainability Report 2018). In a similar vein, in April 2017 H&M announced its strategy turnaround of becoming 100 % circular and renewable by 2030. Furthermore, according to its latest sustainability report, 95% of cotton used is sustainably sourced (H&M Sustainability Report 2018).

3. Highlighted in previous academic articles and studies: Both companies have been in the spotlight of previous scholarly publications on sustainability-related issues [41-44].

4. Coverage in the media and broader public: Both companies face quite adverse corporate reputations mainly due to sweatshop scandals in low-cost production countries as well as accusations of green washing in their sustainability efforts. In a similar vein, C&A is associated with a low-budget image whereas H&M usually epitomizes the term fast-fashion. Both retailers can be considered to spur a certain culture of consumerism and supporting the conventional linear model of fashion production as well as consumption [45].

The second group of documents analysed covers scholarly publications. When identifying and selecting relevant articles we followed the methodological procedure employed in systematic literature reviews [46-50] such as setting up several inclusion and exclusion criteria concerning database selection, date and type of publication and language [24,51-53].

Searching scientific peer-reviewed papers, we used the databases Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost, EconLit with Full Text, Google Scholar and Science Direct. In line with the selected timeframe (2014, 2015 and 2018) English language published academic papers containing the following main keywords were collected: circular/ethical/sustainable fashion, sustainable business model innovations as well as the global fashion industry [54]. As the study is of exploratory nature and the searched keywords are often rephrased or aligned with synonyms a wideranging list of keywords, search Booleans and strings was organized including terms such as clothing care, clothing disposal behaviour, clothing donation, clothing longevity, collaborative consumption, customized apparel, eco-conscious consumption, fashion renting, fashion waste, green fashion, slow fashion, sustainable design. Thus, diverse article search strategies were used, e.g. ‘snowballing’- technique [55,48,56], publications by field experts or screening reference lists for further relevant articles. Then, all found papers were grouped by the published year. In this preliminary sample all articles were examined concerning their thematic appropriateness by reading the abstract or the whole paper. All papers out of focus were deleted from the sample, such as articles mainly focusing on non-economic disciplines, e.g. engineering, chemistry and manufacturing; thus, resulting in a final sample of 130 scientific articles (33 papers in 2014, 32 publications in 2015, and 65 papers in 2018).

For the third group of publications we collected supplementary secondary material, namely publications issued by stakeholders in the broader public. This was considered highly useful for two reasons: First, from a methodological viewpoint this group of publications enables a critical juxtaposition particularly with the practice perspective providing for internal validity of our study. Second, from a content-wise perspective, this approach was deemed important since particularly the development of the circular economy is largely driven by practitioner reports [26]. Aiming at highly qualitative and quantitative material, in a first step a wide range of stakeholders was identified. Doing so, we looked for significant stakeholders in line with the topic, for instance in academic papers and books as well as respective reference lists and conference presentations. The final selection of the stakeholders was based on the following criteria: closely thematically linked to the fashion industry, themes of sustainability, social responsibility and circular economy, scope of independence, range of activities, and reputation [57-59]. The final sample of stakeholders comprises approximately 100 actors including various media (e.g. BBC News), non-governmental and activist organizations (e.g. WWF), political and consultancy agencies (e.g. OECD and BCG), textiles and fashion certification labels or standards (e.g. GOTS) and circular economyrelated supporting organizations (e.g. FWF) and multi-stakeholder boards (e.g. SAI).

Therefore, the database Google was used for a first free search using the three keywords ethical fashion, sustainable fashion and circular fashion, followed by a deeper investigation of the respective websites for gaining further relevant data. Data was included when offering English language, appropriate date, open access and open online source. In line with the organization of grey literature as recommended by Adams RJ, et al. [60] and our academic objectives, we excluded press releases and any type of advertisement and marketing, book reviews, working papers, speeches, as well as other new and social media-related contents. All relevant data and documents were saved as pdf files. In line with categorization process of the academic publications, the data was collected and presented for the year 2014, 2015 and 2018 after screening their appropriateness, trustworthiness, and validity. The final sample comprises 415 publications (89 publications in 2014 and 2015 as well as 237 publications in 2018).

Data analysis

The multi-stakeholder approach aims at a contrasting analysis by means of the software-assisted tool LeximancerTM (version 4.50). As a text-mining and data visualization tool it enables content analysis and data mapping for various disciplines [61], and has already been used and applied in the context of sustainability and for industries, like as mining and apparel [62,63]. Addressing challenges in the context of manual coding, like human framing, subjectivity and stability of inter-coder reliability, this tool mitigates these challenges on the one hand by a programmed lexicographical analysis applying a Bayesian machine-learning technique [64- 66]. On the other hand, an enormous quantity of documents and written data can be analysed in a very reasonable time, far quicker than human analysis. Searching for main concepts and themes in an inductive and iterative procedure LeximancerTM uses elements of descriptive statistics as frequencies, (co-)occurrences and interrelations of words and sentences [61,67,65,68]. Linking all collected sources and grouping words or subsets in underlying texts concepts are created. So, the software can provide a thematic conceptual-based analysis, visualized as core concepts, as well as a semantic or relational examination, presented as connections and relations between the respective concepts [69,70]. A concept map pictures clusters of related concepts – the similar, the closer [61,70] (Harwood et al. 2015; Thomas and Maddux 2009). Themes include often co-occurring concepts and are termed with the most representative concept in the cluster. Moreover, semantic relations between concepts and themes are visualized by relative positions of the concepts – the stronger, the closer. Proximal and overlapping themes denote a closer relation of the respective text documents [33]. Consequently, despite software-based support, interpretation is still challenging and needs to be done carefully and inter subjectively traceable.

In the present research, several concept maps were generated by means of Leximancer™ for all the three groups of publications separately for the years 2014, 2015 and 2018. Overall, the analysis by Leximancer™ revealed 477 concepts among all three groups of publications investigated.

Results and Discussion

In order to enable adequate handling and to address the research questions posed, the overall group of concepts was organized into several subgroups and presented in tables. These subgroups represent different thematic foci of the concepts identified. In line with the research objectives in the study, they relate to (1) social sustainability, (2) general attributes indicating a shift towards a more sustainable and circular fashion industry, and (3) geographical areas. The findings of this classification are presented below.

Concepts relating to social sustainability in the fashion industry

In alignment with previous literature on social sustainability 114 concepts out of the total number of concepts were identified as social sustainability-related. By further fine-graining and narrowing down this initial list 83 concepts were selected for a subsequent detailed examination. The analysis revealed several concepts such as “circular”, “local”, “responsible”, “standards” and “management” that play a role in each of the three groups of publications. Concepts that are relevant to only the group of corporate sustainability reports are for instance “commitment”, “communities” and “partnership”. As opposed to this, concepts such as “education” are included in the groups of academic and stakeholder publications only.

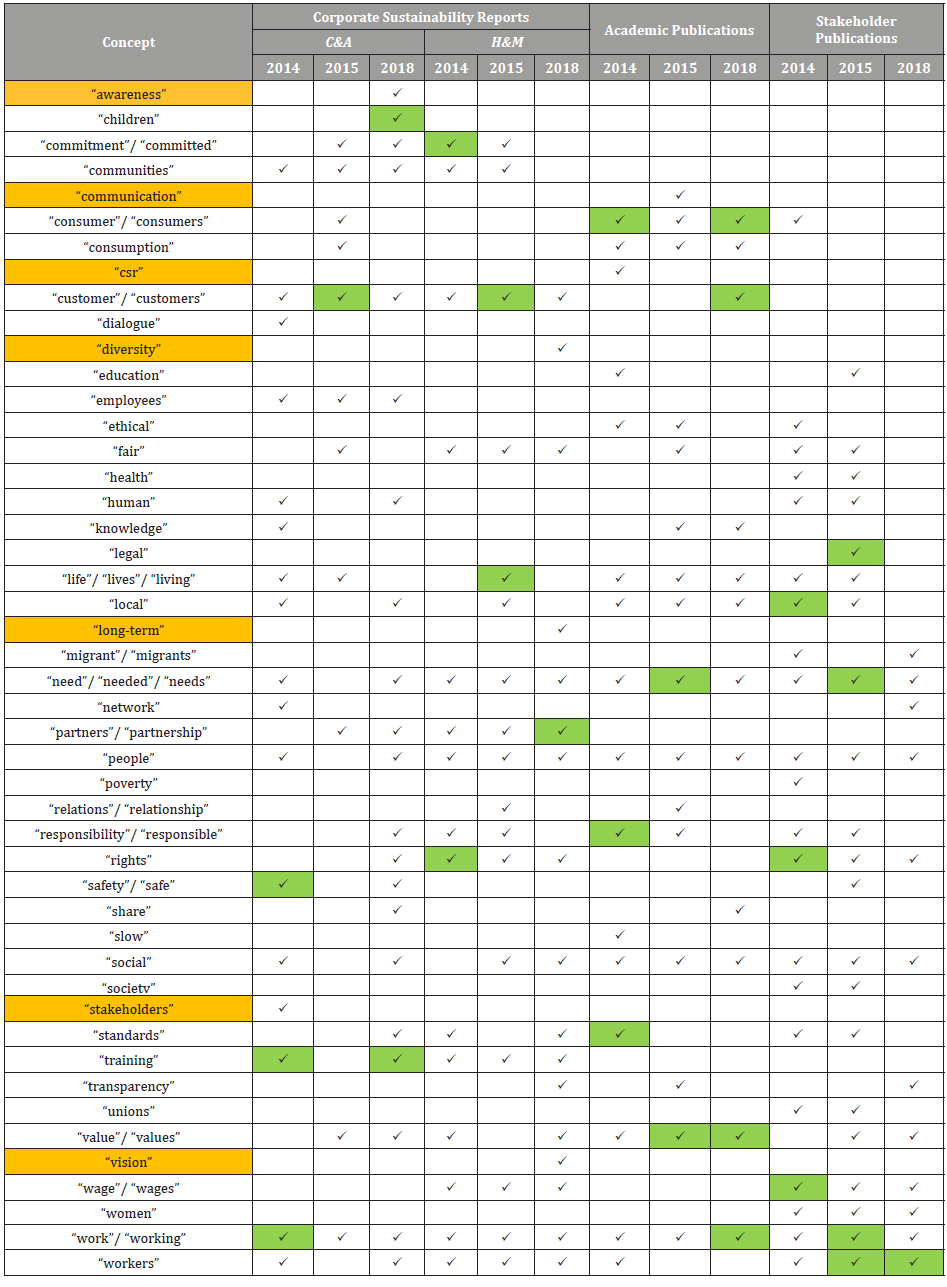

Table 1 illustrates the temporal appearance of selected main concepts closely linked to social sustainability per each group of publication. Exemplarily, the concepts “awareness” and “children” appear only in the concept map of C&A in 2018. They do not appear in any other concept map of H&M or the remaining two groups of publications or in any other year. Vice versa, the concept “diversity” is represented in only the concept map of H&M in 2018. Put differently, it does not play any role in any other concept map of the other groups nor in any other year. Next, when considering the entire period of investigation covered, an increase of visualized concepts in the concept maps generated by LeximancerTM can be noticed for C&A from 20 concepts in 2014 to 28 concepts in 2018. In contrast, the number of concepts visualized for H&M has raised in the same period from 19 concepts in 2014 to 23 concepts in 2018. By referring to academic publications, a decrease of the amount of concepts can be retraced from 22 concepts in 2014 to 18 concepts in 2018. An even more dramatic decline of concepts pictured can be observed in the concept maps of the group of stakeholder publications, thereby falling from 28 concepts in 2014 to 17 concepts in 2018. In addition, as shown in Table 1, there are several concepts that exercise a special role from a time-related perspective:

• The concept “employees” is displayed only consecutively in the concept maps of C&A in all three years (2014, 2015 and 2018).

• The concept “social” is visualized only consecutively in the two groups of academic and stakeholder publications.

• Only the group of stakeholder publications consecutively mirrors the concept “women”.

• The concept “wages” can be found consecutively in the concept maps of H&M and stakeholder publications.

• Only the concept map of C&A in 2018 pictures the concept “children” and even as a single theme. Vice versa, only the concept map of stakeholder publications in 2015 displays the concept “legal” as a concept and even as a single theme.

• The concept “consumption” can be retraced consecutively just in the group of academic publications.

• The concepts “ethical” and “responsible / responsibility” are visualized in academic and stakeholder publications in 2014 and 2015 solely.

• The concept “partners / partnership” appears only consecutively in the concept maps of H&M. In 2018 it is presented even as a single theme.

• With regard to the three concepts “education”, “training” and “knowledge” the following time-related patterns can be deduced. The concept “education” is displayed only in the years 2014 and 2015 in the concept maps of academic and stakeholder publications. In contrast, the concept “training” is visualized in the concept maps of C&A in 2014 and 2015 as a single theme. A consecutive presentation of the concept can be retraced only in the concept maps of H&M. With regard to the concept “knowledge” this is mirrored only in the concept map of C&A in 2014 as well as in the concept maps of academic publications solely in 2015 and 2018.

Furthermore, there are social sustainability-related concepts appearing particularly at the end of the investigation period (2018) that seem to describe, relate or point to a general shift in the industry towards more (social) sustainability and circularity. These concepts include “awareness”, “long-term”, and “network”, “transparency”, “share, standards” or“vision (Table 1).

Table 1:Summary of time-related evolution of main social sustainability-related concepts (Note: Fields marked in green represent themes in the final LeximancerTM concept maps; orange marked concepts are relatively underrepresented).

In sum, however, the concept maps generated by LeximancerTM for the three groups of publications do not embrace a great number of ideas and notions closely associated with social sustainability. These include aspects that refer to social sustainability not only in a cultural sense, but also in a human sense such as “justice”, “care” and “solidarity” [71]. This finding confirms an underrepresented role of the social dimension in sustainability in general and in the wider public compared to other main sustainability dimensions.

Concepts relating to a general trajectory towards a sustainable and circular fashion industry

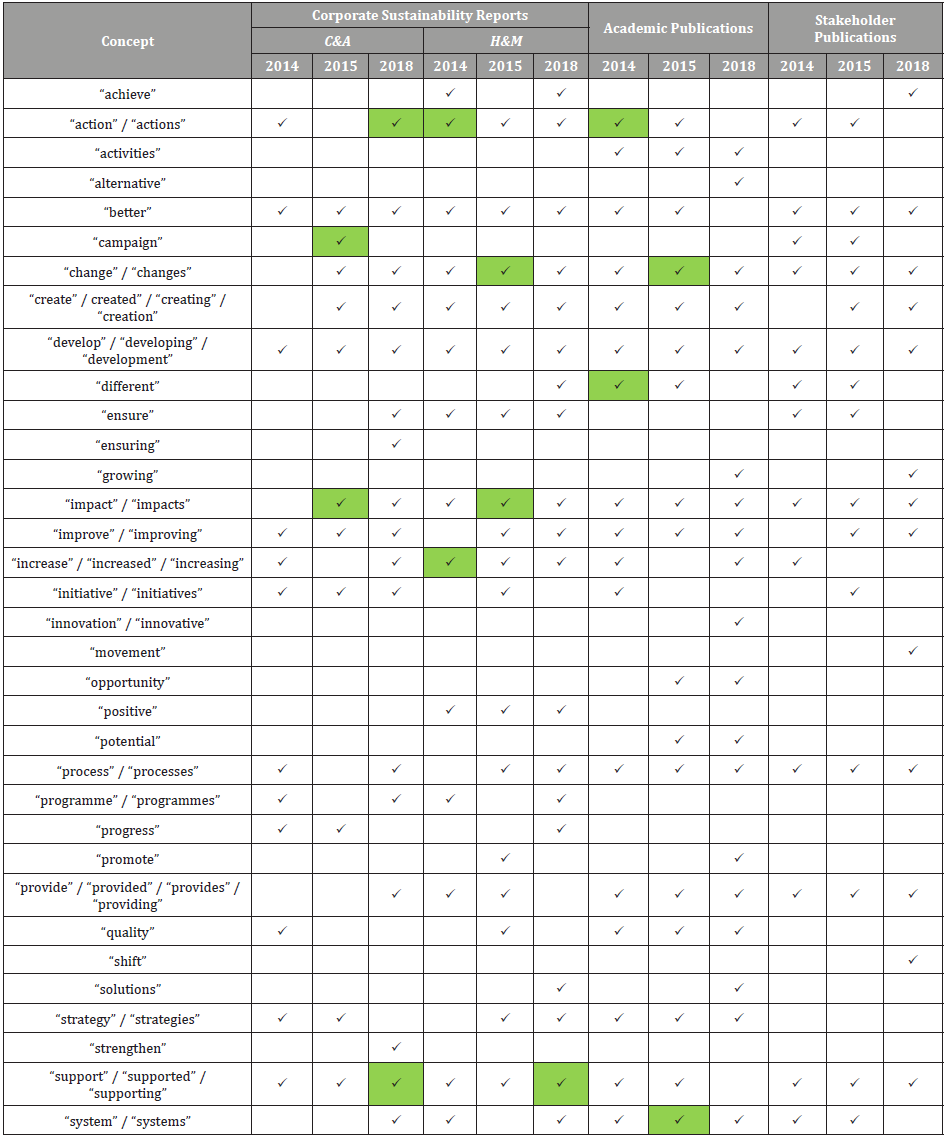

Table 2:Overview of concepts concerning general trajectories towards circular economy (Note: Fields marked in green represent themes in the final LeximancerTM concept maps).

Table 2 depicts those concepts that appear to reflect a wider transformation in the fashion industry. These include concepts such as “development”, “strategies”, “shift”, “progress”, “potential” and “solutions”. The concepts included are to be set in context of the fashion industry’s efforts towards more sustainability and circularity. Exemplarily, the concept “change” appears almost consecutively in all three groups of publications across the period investigated (11 times). This finding proves true also for the concepts “development”, “impact / impacts” and “support” (11 times for each) as well as “improve / improving” (10 times) (Table 2).

In general, however, in comparison to the group of corporate sustainability reports and stakeholder publications, concepts indicating change and transition are increasingly covered in the group of academic publications. This might imply that science is seen as a driving force when it comes to stimulating new approaches, offering solutions for implementing them in practice and evaluating them retrospectively in order to derive general potential, ambiguities, trade-offs and conclusions that are of systemic importance. For example, the concepts “system” and “strategy” are consistently found in all three concept maps throughout the entire period of investigation in the present study. Moreover, the concept “system” is visualized even as a topic in the concept map in 2018 in the group of academic publications. Interestingly, the concept “innovation” also only appears in the concept map of academic publications in 2018.

At the same time, the analysis also reflects the importance of practice as a starting point for change towards sustainability. Companies are confronted with changing external conditions and rising public pressure to which they must respond. In the concept maps generated by LeximancerTM in the present study, this was mirrored by concepts such as “solutions” and “strategy” appearing in the concept map of H&M’s corporate sustainability report in 2018. Even more, the concept “system” was represented in the concept maps of both C&A and H&M in 2018.

In contrast to these findings, the role of stakeholders appears to be less important here – at least as revealed in the concept maps generated by LeximancerTM. Here, only the concepts “changes”, “development” and “shift” were identified in the year 2018; however, some of these concepts appear already earlier in the other groups of publications and do not necessarily refer to larger, interrelated transitions.

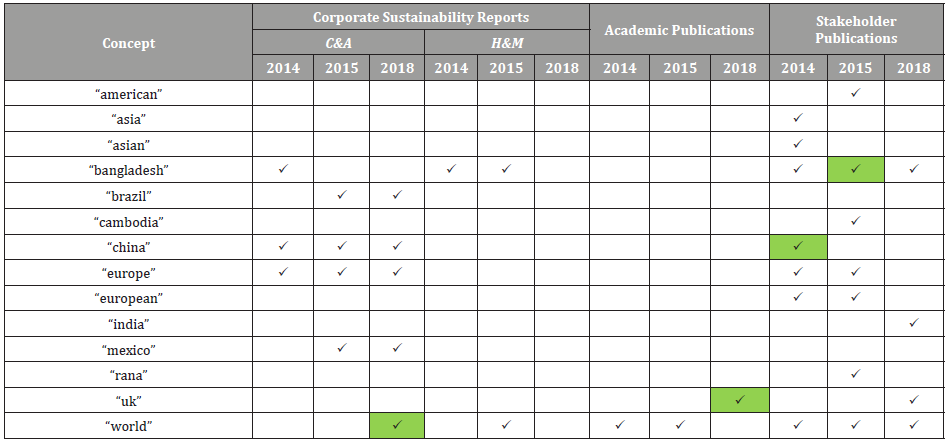

Concepts relating to geographical areas in the fashion industry

Against the background of globally dispersed fashion value chains concepts relating to countries and regions were identified. An overview of these concepts can be depicted from Table 3. These concepts include “Asia”, “Brazil”, “China”, “India” and “Mexico”. Furthermore, the concept “UK” is included, indicating a European focus in the analysis. Both companies analysed, C&A and H&M, display “Bangladesh” as concept in their concept maps of 2014. One year later, in 2015, it can only be still retraced in the concept map of H&M. Interestingly, the concept “Rana” does not appear in any of the concept maps for both companies during the period investigated. Compared to this, the concept maps of stakeholder publications present the concept “Bangladesh” across all three years investigated, in 2015 it appears even as a theme. Furthermore, the concept “rana” is also included, though only in the concept map of 2015. In sharp contrast to this finding, the group of academic publications does not refer to any of the two concepts “Bangladesh” and “rana”. In total, the group of stakeholder publications displays a greater number of concepts with geographical focus, thereby focusing on Asian countries. The concept maps of C&A depict more concepts with a specific regional focus across the period analysed, including “Europe” as well as the countries “brazil”, “Mexico” and “china”. Compared to this finding, H&M appears to emphasize Bangladesh in its sustainability reports. Other regions and countries seem to be not of prior concern. Similar to this finding also academic publications are not related to a particular geographic scope (Table 3).

Table 3:Overview of geographical concepts visualized in concept maps* (Note: Fields marked in green represent themes in the final LeximancerTM concept maps).

Conclusion

The purpose of the study was to explore the evolution and integration of social sustainability-related concepts from a multistakeholder perspective in the fashion industry progressing towards sustainability and circular economy. In doing so, we focused on three different groups of publications including corporate sustainability reports of the two fashion retailers C&A and H&M, academic literature, and stakeholder publications.

Implications

The study makes a number of theoretical contributions. It sheds light on the integration of social sustainability in the transition towards sustainability and circular economy in the fashion industry from a comparative perspective. The manifestation and integration of aspects closely linked to social sustainability, circular economy and systemic shifts are identified and analysed to assess their trajectories of development towards more sustainability and circularity in the fashion industry. Findings prove that social issues are limited to standard understandings in cultural and human senses, but do not inspire the overall discussion further. From a theoretical standpoint, social aspects, not appearing in the concept maps as discussed above, could further be explored. Especially the geographical findings show a wide-spread focus in the fashion industry - partly mirroring countries that are often in the public eye when social injustice, disruptions and mismanagement in fashion companies and their supply chains are witnessed. A stronger connection between regions, their peculiarities and global standards needs to be elaborated. Another avenue for future research could imply the analysis of how social sustainability-related themes and concepts can be aligned to specific components of circular business models of fashion retailers. Moreover, the role of the wider public could be further discussed in a more differentiated way.

Recommendations

As the results show there are differences in themes and concepts between the three groups of publications investigated concerning social sustainability. This invites to greater communication and share of information between the actor groups on the one hand. On the other hand, a clear global framework on social sustainability is needed, so every actor has to integrate basis social standards in daily labour activities. This seems to be pivotal as the geographical scope of the three groups is extremely diverse. Transition has to take into consideration different levels, global, regional, national and local, but only the stakeholder group has recognized this aspect as most important (see Table 3). This is in line with the findings that systemic and ground-breaking transformative concepts are absolutely underrepresented. The concept of a circular economy can initiate revolutionary changes towards a regenerative fashion industry, even including globally operating social standards. However, at this point in time, it fails to do so. As the pushing concepts, like “alternative”, “ensuring”, “innovative”, “movement”, “opportunity”, “potential” and “shift”, are to be found within the academic and the stakeholder group, a clear practical implementation of those concepts into the business world needs to be supported and strengthened by policy, legislation and companies themselves as well as consumers. Concepts of circular economy need to integrate social sustainability issues from the early beginning to enable a sustainable transition from the very outset.

Limitations

Notwithstanding, the present study involves several limitations. First, data is limited to written information and interpreted based on themes, patterns and relations, that can be discussed, yet, cause-effect-relations or causalities are not part of the study and cannot be provided. When focusing on written communication implications on real business activities cannot be drawn, so, the way the data relates with green- and social-washing remains unclear. From a methodological viewpoint further research may employ manual content and discourse analysis [51] (e.g., Mayring 2015) in order to reevaluate patterns and conclusions concerning findings in this study. In addition, interviews with representatives and experts from each of the three groups could be conducted. In this vein, it could also be discussed whether the different patterns concerning concept maps of corporate sustainability reports of C&A and H&M are influenced by different reporting standards employed. Moreover, the entrepreneurial perspective is limited to two companies. Further companies need to be included in the sample representing all sizes and areas of the globe. The results are thus limited to internationally operating companies, and the patterns need to be reflected carefully. In addition, there might be potential flaws in the group of stakeholders since all stakeholder publications retrieved were merged into one group. Though several selection criteria for publications were set up in advance (e.g. year of publication, reputation, same keywords used for search), this determination could be too restrictive. Moreover, the group of stakeholder publications includes only documents in English. While this was considered to be consistent with the methodological criteria set up for the other remaining groups of publications, however, involving stakeholder publications in any other language in a future analysis might deepen this study’s findings and may add further details. Another language constraint is the selection of academic literature by access. Non-accessible documents could provide essential information we did not consider in this study. Language per se limits the variety of information. A further limitation of this research relates to an only small period of investigation. This is partly due to given restrictions concerning the availability of full corporate sustainability reports in English of C&A. Here, further representative companies need to be analysed in order to enhance the reliability of the results. Finally, the interpretation of the concept maps retrieved by LeximancerTM as well as the alignment of concepts to certain thematic foci is partly a matter of researchers’ subjectivity and possibly biased by an implicit knowledge of relevant publications.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Patten LA (2019) Insight into emerging opportunities for sustainable-led strategies in textiles. Journal of Textile Science & Fashion Technology 4: 1-3.

- Siegle L (2019) Burning issue: how fashion's love of leather is fuelling the fires in the Amazon.

- Köksal D, Strähle J, Müller M, Freise M (2017) Social sustainable supply chain management in the textile and apparel industry: a literature review. Sustainability 9(1): 100.

- Human Rights Watch (2020) Brands abandon Asia workers in pandemic.

- Kelly A (2020) Garment workers face destitution as Covid-19 closes factories.

- Fashion Revolution (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on the people who make our clothes.

- UN Global Compact (2019) Social sustainability.

- Müller-Christ G (2001) Sustainable Resource Management: An Economic Ecological Foundation. Marburg, Metropolis.

- Fifka MS (2018) CSR and fashion. Sustainable management in the clothing and textile industry. Heinrich P (edt), Springer, Berlin, Germany, pp. 13-26.

- Turker D, Altuntas C (2014) Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion industry: an analysis of corporate reports. European Management Journal 32(5): 837-849.

- Henninger CE, Alevizou PJ, Oates CJ (2016) What is sustainable fashion? Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 20: 400-416.

- Bidmon CM, Knab SF (2018) The three roles of business models in societal transitions: new linkages between business model and transition research. Journal of Cleaner Production 178: 903-916.

- Hirscher AL, Niinimäki K, Joyner Armstrong CM (2018) Social manufacturing in the fashion sector: new value creation through alternative design strategies? Journal of Cleaner Production 172: 4544-4554.

- Austgulen MH (2016) Environmentally sustainable textile consumption – what characterizes the political textile consumers? Journal of Consumer Policy 39: 441-466.

- Lüdeke-Freund F, Gold S, Bocken NMP (2018) A review and typology of circular economy business model patterns. Journal of Industrial Ecology 23(1): 36-61.

- Markard J, Raven R, Truffer B (2012) Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Research Policy 42(6): 955-967.

- De Angelis R, Howard M, Miemczyk J (2018) Supply chain management and the circular economy: towards the circular supply chain. Production, Planning & Control 29(6): 425-437.

- Hopkinson P, Zils M, Hawkins P, Roper S (2018) Managing a complex global circular economy business model: opportunities and challenges. California Management Review 60(3): 71-94.

- Nußholz JLK (2018) A circular business model mapping tool for creating value from prolonged product lifetime and closed material loops. Journal of Cleaner Production 197(1): 185-194.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2019) Concept: What is a circular economy? A framework for an economy that is restorative and regenerative by design.

- Lahti T, Wincent J, Parida V (2018) A definition and theoretical review of the circular economy, value creation, and sustainable business models: where are we now and where should research move in the future? Sustainability 10(8): 2799.

- Geissdoerfer M, Savaget P, Bocken NMP, Hultink EJ (2017) The circular economy: a new sustainability paradigm? Journal of Cleaner Production 143: 757-768.

- Tura N, Hanski J, Ahola T, Ståhle M, Piiparinen S, et al. (2019) Unlocking circular business: a framework of barriers and drivers. Journal of Cleaner Production 212: 90-98.

- Merli R, Preziosi M, Acampora A (2018) How do scholars approach the circular economy? A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 178: 703-722.

- Levänen J, Lyytinen T, Gatica S (2018) Modelling the interplay between institutions and circular economy business models: a case study of battery recycling in Finland and Chile. Ecological Economics 154: 373-382.

- Kirchherr J, Reike D, Hekkert M (2017) Conceptualizing the circular economy: an analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation & Recycling 127: 221–232.

- Geissdoerfer M, Morioka SN, Monteiro de Carvalho M, Evans S (2018) Business models and supply chains for the circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production 190: 712-721.

- Bocken NMP, de Pauw I, Bakker C, van der Ginten B (2016) Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering 33: 308-320.

- Bocken NMP, Miller K, Weissbrod I, Holgado M, Evans S (2017) Business model experimentation for circularity: driving sustainability in a large international clothing retailer. Economics and Policy of Energy and the Environment (EPEE) 1: 85-122.

- Arnold M (2017) Fostering sustainability by linking co-creation and relationship management concepts. Journal of Cleaner Production 140(1): 179-188.

- Manninen K, Koskela S, Antikainen R, Bocken N, Dahlbo H, et al. (2018) Do circular economy business models capture intended environmental value propositions? Journal of Cleaner Production 171: 413-422.

- Moreau V, Sahakian M, van Griethuysen P, Vuille F (2017) Coming full circle: why social and institutional dimensions matter for the circular economy. Journal of Industrial Ecology 21(3): 497-506.

- Korhonen J, Honkasalo A, Seppälä J (2018) Circular economy: the concept and its limitations. Ecological Economics 143: 37-46.

- Lieder M, Rashid A (2016) Towards circular economy implementation: a comprehensive review in context of manufacturing industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 115(1): 36-51.

- Global Fashion Agenda (GFA) (2020) A manifesto to deliver a circular economy in textiles.

- German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ) (2019) Circular economy in the textile sector.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017) A new textiles economy: redesigning fashion’s future.

- Ruhnke K, Gabriel A (2013) Determinants of voluntary assurance on sustainability reports: an empirical analysis. Journal of Business Economics 83: 1063-1091.

- C&A (2019) About C&A: Caring for generations.

- H&M (2019) At a glance: H&M Group.

- Shen B (2014) Sustainable fashion supply chain: lessons from H&M. Sustainability 6: 6236-6249.

- Hansen EG, Schaltegger S (2013) 100 per cent organic? A sustainable entrepreneurship perspective on the diffusion of organic clothing. Corporate Governance 13(5): 583-598.

- Graafland JJ (2002) Sourcing ethics in the textile sector: the case of C&A. Business Ethics: A European Review 11(3): 282-294.

- Kolk A, van Tulder R (2002) The effectiveness of self-regulation: Corporate codes of conduct and child labour. European Management Journal 20: 260-271.

- Hansen EG, Schaltegger S (2016) Mainstreaming of sustainable cotton in the German clothing industry. In: Muthu SS, Gardetti MA (edts) Sustainable fibres for fashion industry: environmental footprints and eco-design of products and processes. Springer, Singapore, pp. 39-58.

- Homrich AS, Galvão G, Gamboa Abadia L, Carvalho MM (2018) The circular economy umbrella: trends and gaps on integrating pathways. Journal of Cleaner Production 175: 525-543.

- Buliga O, Scheiner CW, Voigt KI (2016) Business model innovation and organizational resilience: towards an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of Business Economics 86: 647-670.

- Gerritsen-van Leeuwenkamp KJ, Joosten-ten Brinke D, Kester L (2017) Assessment quality in tertiary education: an integrative literature review. Studies in Educational Evaluation 55: 94-116.

- Schallehn H, Seuring S, Strähle J, Freise M (2019) Customer experience creation for after-use products: a product–service systems-based review. Journal of Cleaner Production 210: 929-944.

- Camacho-Otero J, Boks C, Pettersen IN (2018) Consumption in the circular economy: a literature review. Sustainability 10(8): 2758.

- Ansari ZN, Kant R (2017) A state-of-art literature review reflecting 15 years of focus on sustainable supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production 142(4): 2524-2543.

- Quarshie AM, Salmi A, Leuschner R (2016) Sustainability and corporate social responsibility in supply chains: the state of research in supply chain management and business ethics journals. Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 22(2): 82-97.

- Rajeev A, Pati RK, Padhi SS, Govindan K (2017) Evolution of sustainability in supply chain management: a literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 162: 299-314.

- Ritala P, Huotari P, Bocken N, Albareda L, Puumalainen K (2018) Sustainable business model adoption among S&P 500 firms: a longitudinal content analysis study. Journal of Cleaner Production 170: 216-226.

- Neutzling DM, Land A, Seuring S, Machado do Nascimento LF (2018) Linking sustainability-oriented innovation to supply chain relationship integration. Journal of Cleaner Production 172: 3448-3458.

- Tukker A (2015) Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy: a review. Journal of Cleaner Production 97: 76-91.

- Gwilt A (2018) A practical guide to sustainable fashion, 3rd (edn). London, New York, Bloomsbury, USA.

- Eins B (2018) Bestenliste Consulting.

- Diekamp K, Koch W (2010) Eco Fashion: Top-labels entdecken die Grüne Mode. Stiebner Verlag GmbH, Germany.

- Adams RJ, Smart P, Huff AS (2017) Shades of grey: guidelines for working with the grey literature in systematic reviews for management and organizational studies. International Journal of Management Reviews 19(4): 432–454.

- Harwood I, Gapp RP, Stewart HJ (2015) Cross-check for completeness: exploring a novel use of Leximancer in a Grounded Theory Study. The Qualitative Report 20: 1029-1045.

- Kim D, Kim S (2017) Sustainable supply chain based on news articles and sustainability reports: text mining with Leximancer and DICTION. Sustainability 9(6): 1008.

- Ranängen H, Lindman Å (2017) A path towards sustainability for the Nordic mining industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 151: 43-52.

- Antikainen M, Valkokari K (2016) A framework for sustainable circular business model innovation. Technology Innovation Management Review 6: 5-12.

- Young L, Wilkinson I, Smith A (2015) A scientometric analysis of publications in the Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing 1993–2014. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing 22(1-2): 111-123.

- Bryman A (2015) Social research methods. Oxford, Oxford University Press, USA.

- Gautami Fernando A, Suganthi L, Sivakumaran B (2014) If you blog, will they follow? Using online media to set the agenda for consumer concerns on ‘Green washed’ environmental claims. Journal of Advertising 43(2): 167-180.

- Angus D, Rintel S, Wiles J (2013) Making sense of big text: a visual-first approach for analysing text data using Leximancer and Discursis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 16: 261-267.

- Bigi A, Bonera M, Bal A (2016) Evaluating political party positioning over time: a proposed methodology. Journal of Public Affairs 16(2): 128-139.

- Thomas DA, Maddux CD (2009) Analysis of asynchronous discourse in web-assisted and web-based courses. The Researcher 22: 1-16.

- Mayring P (2015) Qualitative content analysis: basics and techniques. Weinheim, Basel, Beltz.

-

Marlen Gabriele Arnold, Katja Beyer. Sustainability Transitions in Disclosures in the Fashion Industry: Comparative Insights into Social Sustainability, Circularity and Systemic Shifts. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech. 5(3): 2020. JTSFT.MS.ID.000615.

-

Social sustainability, Sustainability transitions, Circular economy, Fashion industry, Stakeholder; Software-based content analysis, LeximancerTM

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.