Opinion

Opinion

Right-Sized Consumption: Should Doughnut Economics Inform the Textile and Apparel Industry?

Jana Hawley, College of Merchandising, Hospitality and Tourism, University of North Texas UNT, USA.

Received Date: September 01, 2021; Published Date: September 13, 2021

Abstract

One of the toughest challenges the textile and apparel industry faces is how to Right-Size Consumption in a way that supports our environment while at the same time sustains profitable businesses. Companies are scrambling to find the right balance that meets this consumer shift while at the same time endures the demands of shareholders in a capitalist marketplace. Right-sized consumption is embedded in important economic, political, and social issues. Major corporations measure their success by stock market performance and constantly strive to sell more and more so that shareholders are happy. On the other hand, consumers are moving away from excessive consumption behavior to a more mindful approach that honors substance and sense of purpose [1]. As this shift occurs, a new economic model needs to be considered that allows businesses to flourish in an environment where sustainability becomes more important than quantity of sales. The purpose of this concept paper is to inspire a discussion on how ITAA scholars can begin to develop an economic model of sustainability where environment, economics, and humans not only co-exist- but thrive.

Keywords:Consumption; Sustainability; Behavioral Economics; Capitalism; Textiles; Apparel

Opinion

Depending on your point of view, often influenced by your political leanings, consumerism can be fundamental and benign or rampant and dangerous. No doubt, it is often a hot debate. A few years ago, the marketplace drove our consumption behavior with monikers such as “retail therapy” or “shop ‘til you drop”. More recently, however, consumers have begun to replace over-the-top consumption with mindful and intelligent consumption.

One of the toughest challenges the textile and apparel industry faces is how to Right-Size Consumption in a way that supports our environment while at the same time sustains business profitability. Companies are scrambling to find the right balance that meets this consumer shift while at the same time endures the demands of shareholders in a capitalist marketplace. Right-sized consumption is embedded in important economic, political, and social issues. Major corporations measure their success by stock market performance and constantly strive to sell more and more to satisfy shareholder expectations. On the other hand, consumers are moving away from excessive consumption to a more mindful approach that honors substance and sense of purpose [1]. As this shift occurs, a new economic model needs to be developed that allows businesses to flourish in an environment where sustainability becomes more important than quantity of sales. The purpose of this concept paper is to inspire a discussion on whether Raworth’s [2] doughnut economics theory can be used as a better economic model of sustainability where environment, economics, and humans not only co-exist can be--but thrive. I do not purport to be an economist, or even to understand it beyond the basic theories. However, I argue here that the basic teachings of economics fail to include the important concept of environment and nature. Here I have illustrated how two global apparel companies fit into Raworth’s Doughnut Economics model.

The Challenge of Neoclassical Economic Theory

Today’s dominate microeconomic theories is the neoclassical approach which relies on supply and demand to explain an individual’s rationality and ability to maximize utility or profit. For most of the 20th century, growth was widely thought to be the remedy for all economic problems. For example, to solve poverty, simply grow the economy and watch wealth trickle down. Unemployment issues are answered by increasing demand for goods and services thereby opening the job market. Environmental degradation is resolved with the Kuznets curve [3]. This approach to economics focuses on the determination of good, outputs, and income distribution. Originally introduced by Thorstein Veblen [4], neoclassical economics has three central assumptions:

1. People have rational preferences that are associated with values.

2. Individuals maximize utility and firms maximize profits.

3. People act independently based on full and relevant information.

From these three basic assumptions, neoclassical economists have built widely accepted theories that purport to explain the allocation of scare resources among alternative ends. Neoclassical economists have given us additional theories including the theory of the firm, demand curves, factors of production, and marginal productivity to name a few. Furthermore, neoclassical economists assert that human nature is self-interested, competitive, and calculating. This result is the goal of endless growth but with a result of those who win and those who lose.

For decades, critics have identified problems inherent in neoclassical economic theories, stating that too much emphasis is given to mathematical models without enough attention to whether these actually describe the real economy. Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz argued:

“One cannot ignore the possibility that the survival of the [neoclassical] paradigm was partly because the belief in that paradigm, and the policy prescription, has served certain interests” [5].

Nordaus, the 2018 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences argued that nature dictates the main constraints on economic growth [6] and Dasgupta [7] argues that nature is fundamental to human well-being and thus, nature should be part of economic reasoning and theory development and Raworth argues that neoclassical economics has a sociological and ecological void [8]. She argues that instead of economic growth we should start our understanding with the fundamentals that we care about: People and planet. In other words, we should end the assumption that an environmental agenda is somehow separate or opposed to basic economic principles such as distribution of resources.

Conventional economic theory is rooted in the belief that there are no limits to growth. They believe that human ingenuity is infinitely substitutable for limited naturel resources. Traditional economic models are based on using up resources in ways that accurately reflect the tastes and preferences of individual consumers. Society, the environment, and even preferences for no-consumption goods are considered external to the economic decision-making process. These theories go back to the days of Rostow [9] where economic growth was outlined through 5 easy steps leading, finally, to high-mass consumption. However, the paradigm of the 20th century no longer holds true in today’s world. We must recognize that economies do not exist in a void. Rather the economy is part of a “subsystem of the finite biosphere that supports is” [3]. Furthermore, if economic expansion happens too quickly or without controls, the natural capital (fish, fossil fuels, waters) suffers. If we don’t heed the warnings, we may be faced with an ecological catastrophe. Daly HE [3] points out that conventional macroeconomists do not have an analogous ‘when to stop’ rule. They argue that growth is unlimited. But I contend that even though many economists still do not agree, we must make the transition to a sustainable economy- one that considers the limits of the natural environment .

A Sustainable Economy

Sustainability discussions have received much attention among ecologists, environmental engineers, textile and apparel scholars, and other members of the scientific and business community. In recent years, environmental sustainability has become a key managerial issue with both researchers and practitioners assigning attention to the issue as they face the challenge of achieving balance between economic needs and environmental concerns. Often times, these needs and concerns seem at loggerheads with each other. Yet, companies are held responsible for environmental and social problems and we must find a right-sized solution. Grimsley [10] defined a sustainable economy as one that “attempts to satisfy the needs of humans but in a manner that sustains natural resources and the environment for future generations”.

It is well documented that the textile and apparel industry has very high environmental and social impact. It accounts for 9.3% of the world’s employees [11] (World Trade Organization, 2008) and the production processes, in particular dyeing/drying/finishing, generate high environmental impact [12]. In addition, both natural and synthetic fibers have inputs (e.g. water, fertilizers, pesticides, petroleum, energy, toxic waste) that impact the environment. Significant impacts are also made when considering the global scale of the industry as the transport of goods from low-labor cost countries to consumers in US and Europe demands high inputs [13].

The emergence of sustainability as a major public issue reflects a fundamental challenge to the assumption of unlimited growth. Sustainability is people-centered [14]. It is about sustaining a desirable quality of life for future generations. The United Nations notes that climate change is now affecting every country on the continent, disrupting national economies, affecting lives, and costing people and communities [15]. The UN Sustainable Development Summit of 2020 adopted the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) but placed in into a COVID recovery framework. It calls on facts, data, and opportunities we have as a human family to reimagine and reshape the future (https://www.un.org/ sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/). A commentary in The Lancet argues that we must think about ‘wellbeing’ rather than sustainability where well-being depends on enabling every person to lead a life of dignity and opportunity, while safeguarding the integrity of Earth’s life-supporting systems [16].

Doughnut Economics: A New Economic Model of Sustainability

It has become clear that 20th century economic theories of unlimited growth no longer make sense in a world where environmental degradation warnings are commonplace. More and more consumers care about a healthy ecosystem. Yet, collectively, we have not made significant progress on reducing the damage business does across the globe. Reliable metrics that measure business impact on the environment have not been well-developed. We need to get to a point of “true cost accounting”- where successful companies are synonymous with sustainable business. In other words, we need to put a price on the priceless [17].

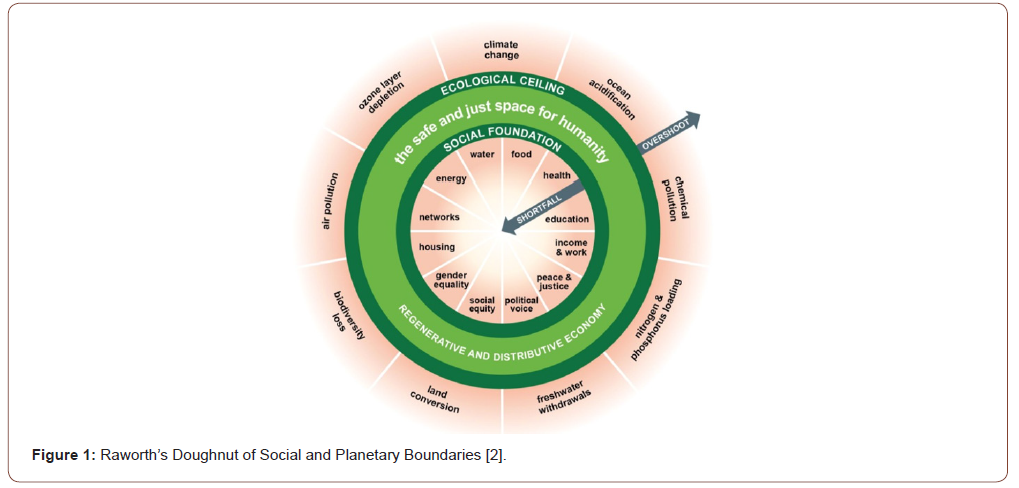

In an April 2018 TedTalk [18], Oxford economist, Kate Raworth proposed the Doughnut Economic Model for the 21st century. She argued that growth economics no longer work and proposed a new doughnut-shaped model. The doughnut model suggests that we transform our capitalist worldview obsessed with growth into a more balanced, sustainable perspective that allows both humans and our planet to thrive. The central premise to her theory is that we must meet the human rights of all people within the capacity of Earth’s life-support systems. She calls this the “sweet spot” between social and planetary boundaries [19]. While Raworth’s work certainly takes a giant step forward in rethinking economics, as professionals in textiles and apparel, we must ask whether the doughnut model fits with the sustainability and economic issues of the textile and apparel industry.

In Raworth’s [2] description of doughnut economics, she asks, “What enables human beings to thrive”. She calls on the 2015 United Nations Sustainability Goals to define the human social needs then surrounds this with the ecological ceiling. The result is the doughnut. Figure 1 Illustrates Raworth’s Doughnut Theory (Figure 1).

For most of the 20th century, economic thinking told us that GDP growth was the measure for progress, with upward trend lines that supported this claim. But with fair warning from climate scientists, we must change the direction of the trend lines and come into a ‘dynamic balance” [2] that supports human well-being and Earth’s boundaries.

Doughnut Economics for the Textile and Apparel Industry?

Textile and apparel companies are in constant negotiation between daily operating procedures and meeting shareholder expectations. Neoclassical theories would claim that markets determine what makes a firm efficient. This has often resulted in companies that push the limits of the law and the boundaries of our planet to maximize shareholder values.

The real challenge is to create a cultural shift where consumers consume less. In spring 2021, Levi Strauss & Co launched a new ad campaign that addresses a fundamental contribution that consumers can make to support environmental causes. At the same time, the “Buy Better, Wear Longer” campaign argues that better quality will also support the profits that Levi’s expects to run a successful business (https://www.levistrauss.com/2021/04/22/ levis-launches-buy-better-wear-longer-campaign/). To view a selection of their ads, please see https://www.levi.com/US/en_ US/. This campaign contradicts our long-held ideals of marketing and economic growth [20]

The conceptual idea of mindful consumption is embedded in ‘happiness’ literature. Sheth JN, et al. [21] (2011) found that happiness is not necessarily obtained from having more things or to consume more. Berntsson, et al. [22] argued that the millennial generation may provide the tipping point that moves consumption behavior to one that values sustainability over ‘shop ‘til you drop’.

It is time for textile and apparel scholars to come together to develop its own model of economic sustainability. Our programs are often deeply connected to industry as we prepare our students for careers. So how do we balance the need for new perspective at the same time we steward are relationships with industry? How do we nudge industry to make better decisions that support social and planetary needs? How do we muster the ethical courage required to make sure that our industry thrives well into a long-view of the future?

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Havas Global Comms (2010) 72% are shopping more carefully and mindfully than they used to.

- Raworth K (2017) Doughnut Economics: 7 Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Daly HE (2005) Economics in a Full World. Sci Am 293(3): 100-107.

- Veblen T (1900) The Preconceptions of Economic Science- III. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 14(2): 240-269.

- Stiglitz J (2001) Nobel Prize lecture. Information and the change in the paradigm in economics.

- Nordhaus WD (2019) Facts- 2018. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB.

- Dasgupta P (2001) Human Well Being and the Natural Environment. Oxford: Oxford University Press, UK.

- Meaning EY (2017) A call to creativity from Kate Raworth’s. ‘Doughnut Economics’.

- Rostow WW (1959) The stages of economic growth. The Economic History Review 12(1): 1-16.

- Grimsley S (2018) What is sustainable economic growth? Study.com.

- World Trade Organization (2008) International Trade Statistic.

- De Brito MP, Carbone V, Blanquart CM (2008) Towards a sustainable fashion retail supply chain in Europe: Organization and performance. International Journal of Production Economics 114(2): 534-553.

- Caniato F, Caridi M, Crippa L, Moretto A (2012) Environmental sustainability in fashion supply chains: An exploratory case based approach. International Journal of Production Economics 135(2): 659-670.

- Ikerd JE (1997) Toward an economics of sustainability.

- UN World Commission (2020) Our Common Future Report.

- The Lancet (2017) A doughnut for the Anthropocene: humanity’s compass in the 21st

- Chouinard Y, Ellison J, Ridgeway R (2011) The Sustainable Economy. Harvard Business Review.

- Raworth K (2018) A healthy economy should be designed to thrive, not grow [TedTalk].

- Raworth K (2012) Want to get into the doughnut? Tackle inequality.

- (2020) United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

- Sheth JN, Sethia NK, Srinivas S (2011) Mindful consumption: A customer-centric approach to sustainability. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science 39: 21-39.

- Berntsson S, Forsgren S (2018) The millennial mind: A qualitative study on how to communicate sustainability to reduce consumption (Unpublished master’s thesis). The Swedish School of Textiles. University of Boras, Sweden.

-

Jana Hawley. Right-Sized Consumption: Should Doughnut Economics Inform the Textile and Apparel Industry?. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech 9(2): 2021. JTSFT.MS.ID.000707.

-

Consumption, Sustainability, Behavioral Economics, Capitalism, Textiles, Apparel

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.