Research Article

Research Article

Increasing Consumer Participation in Textile Disposal Practices: Implications Derived from an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour on Four Types of Post- Consumer Textile Disposal

Rozanne Henzen1* and Sara Pabian2

1Antwerp Management School, Belgium

2University of Antwerp, Belgium

Rozanne Henzen, Sustainable Transformation Lab, Antwerp Management School, Belgium.

Received Date: November 05, 2019; Published Date: November 19, 2019

Abstract

Consumers decide when, where and how they dispose of their textiles and therefore determine their lifespan, destination and potential of textiles. An extended Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) that includes personal norm regarding textile recycling; industry awareness regarding the negative issues surrounding the textile industry; and knowledge of textile recycling has been used to explore the drivers of four consumer textile disposal intention categories: incentive and non-incentive-based textile disposal, extending the lifespan of textiles and binning unwanted textiles between household waste. The online survey (n = 491) showed that there is a gap between knowledge on the disposal method, previous behaviour and intention. In addition, it showed that subjective norm, personal norm and industry awareness all have a positive influence on the intention to dispose without incentive, while personal norm and industry awareness have a negative influence on the intention to bin unwanted textiles between household waste. The variables are insignificant predictors of the intention to dispose of textiles in exchange for an incentive and the intention to extend the lifespan of textiles. Besides, the incentive-based textile disposal has the lowest intention score, indicating that current incentives, such as a 10% discount on a subsequent purchase, do not sufficiently stimulate consumers to bring back their unwanted textiles. Based on the findings, some suggestions are made to the textile industry, government organizations and policymakers to strengthen their promotional campaigns and textile disposal methods. Contrary to previous research results, knowledge of textile recycling is not a significant predictor of consumer textile disposal intention. In addition, the results show that perceived behavioral control, one of the original TPB variables, is not a significant predictor of any of the behavioral intentions. This suggests that perceived behavioral control could be excluded from the TPB model in research on textile disposal behaviour.

Keywords: Textile disposal; Textile recycling; Textile waste; Theory of planned behaviour; Consumer behaviour; Recycling intention; Disposal intention; Quantitative research

Abbreviations: TPB: Theory of Planned Behaviour

Introduction

Sustainable clothing consumption and consumer behaviour has been studied by many researchers, but less attention has been given to the last stage in consumer behaviour: the disposal of textile products. For the purpose of this research textiles are defined as clothing (including underwear, swimwear, socks, hats); shoes; leather goods (handbags, belts); bed and bath linen (sheets, duvet covers, pillowcases, blankets, towels, washcloths), mattresses excluded; and decorative textile (e.g., curtains), carpets excluded [1]. ‘Disposal’ refers to getting rid of unwanted textiles at the end of life stage with their current owner, regardless of whether the item is disposed of as waste, for recycling, or reuse [2].

Since 2000, the global clothing production has been doubled [3]. In recent years consumers and the industry have become increasingly aware of the negative issues surrounding the textile industry. Several brands and global retailers started addressing environmental and social challenges, either in their supply chain or in their communication. However, this does not directly tackle the root cause of the textile industry’s wasteful nature: low clothing utilization and low rates of post-consumer recycling. The textile industry only recycles 13 percent of their total material input. Most of this is downcycled into insulation material, wiping cloths, and mattress stuffing, all of which are very difficult to reuse, thus creating the material’s final usage. Furthermore, the industry recycles less than 1 percent of the total material input used to produce clothing in order to create new clothing [3]. The sum of yearly discarded textiles in the European Union is 2.29 billion kilograms [4].

Consumers decide when, where, and how they dispose of their textiles, and therefore determine their lifespan, destination, and potential. Currently, across Europe, it is estimated that consumers dispose between 80 and 85 percent of their unwanted textiles between regular household waste, resulting in incineration or landfilling [5]. This is causing environmental problems, increased carbon emissions, monetary and other losses for themselves and the industry.

Laitala K [2] stated in her synthesis of research results on consumers’ clothing disposal behaviour between 1980 and 2013, that the majority of the studies concentrated on disposal destinations and motivations behind the selection of specific disposal methods, followed by demographics. Fewer studies have been conducted with a focus on the reasons behind textile disposal. The studies within these categories mainly focus on factors like policy change, interest in fashion, sustainable consumption, emotional value, the accessibility of disposal methods, or a combination between them [2]. The intention to engage in textile disposal behaviour is not part of the four identified research topics identified in the research synthesis. Besides, multiple studies left out male respondents and the root cause of textile waste: the binning of textiles. Additionally, none of the studies used consumer experiments. More importantly, most of the research conducted on this topic occurred before or during the rise of the fast fashion industry and the Rana Plaza disaster in 2013.

Morgan LR, et al. [6] argued that the unawareness of the need for clothing recycling is thought to be a result of lack of media coverage. Four years after their research, sparked by the Rana Plaza disaster, international attention and media coverage increased. Brands and retailers pledged to change their way of working, major global retailers implemented take-back schemes and created collections made from organic, sustainable or recycled materials. Hereby we could argue that consumers should be more aware and more informed about the environmental and social impact of clothing manufacturing and disposal, than during most of the research conducted on textile disposal. Consumers should consequently be more aware of the need for clothing recycling.

The present study will try to overcome the aforementioned shortcomings by taking the whole range of disposal methods into account, questioning males and females from all age categories and concentrating on multiple disposal motivations. As behavioral intention is the immediate precedent of the actual behaviour, we will use the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) as a starting point. The intention to engage in textile disposal can be studied and measured through a survey and used as a predictor for the actual textile disposal behaviour. Besides, to make the disposal of textiles more tangible, we included a picture scenario into the survey.

The Theory of Planned Behaviour

The theory of planned behaviour (TPB)

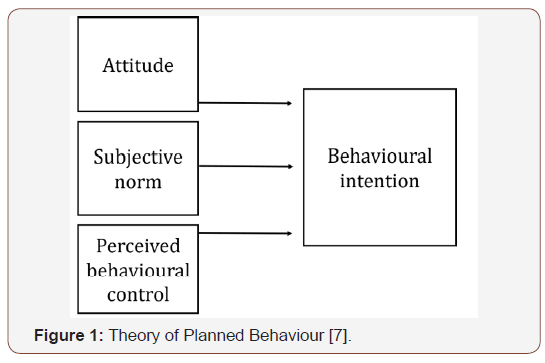

TPB provides a theoretical framework to predict an individual’s intention to engage in a certain behaviour over which they are able to exert self-control [7]. It posits that individual behaviour is driven by behavioral intentions. Therefore, it is assumed that behavioral intention is the immediate precedent of that behaviour. The stronger the intention, the more likely the behaviour of interest will be executed. TPB distinguishes between three types of beliefs: behavioral, normative and control. Where behavioral beliefs refer to attitude; normative beliefs refer to a person’s perception of the social and subjective norms surrounding the behaviour of interest; and control beliefs refer to an individual’s perception of factors that may ease or obstruct the degree to which they have control over the execution of the behaviour of interest. These three believes are the key determinants of behavioral intention (Figure 1).

TPB and textile disposal behaviour

Whilst TPB is one of the most used theories in research on general household recycling, it has hardly been used in the context of consumer textile disposal behaviour. Pieters RG [8] used the Theory of Reasoned Action, which is the precursor of TPB, to identify the determinants of the actual disposal behaviour, which are perceived benefits and costs, motivation (attitude and intention) and the ability to engage in disposal behaviour (knowledge and habit) [8]. Weber S, et al. [9] used TPB as a foundation for their survey on consumer textile waste management, noting that the survey will reflect the intended behaviour and not the actual behaviour itself9. It showed that consumers with a higher score on fashion interest and shopping frequency have a lower disposal rate than consumers with a lower score. The researchers argued this is due to the fact that increased consumption does not increase the tendency to ’throwaway’ clothes but indicated a positive attachment to clothing. Consumers with a higher score are therefore more interested in reselling, take-back schemes and swapping their unwanted clothing. Stols M [10] combined the TPB with the Norm- Activation Theory to investigate the relationship between female consumers’ pro-environmental textile disposal motivation and intention to dispose of textiles by donating, reselling, reuse and recycling. The strongest predictor of textile disposal intention is attitude and perceived behavioral control was the weakest significant

As noted earlier, the TPB has been used extensively to explain general household recycling. These studies might provide indications for the usability of the theory to explain the behaviours under study, namely different forms of textile disposal behaviour. The goal of the recycling of household waste is to use less raw materials by keeping the already used materials in the production and consumption cycle as long as possible. Recycling consists of finding new functions for materials that have lost their original function for their first user or of finding a new user8. Waste must be sorted, prepared and stored, therefore the actual disposal of waste and the corresponding behaviour requires a notable effort. Consequently, a decision to engage in recycling is presumably complex. To identify that behaviour or its behavioral intention, a number of different factors must be taken into consideration. As TPB identifies these factors, it is no surprise this theory has often been applied. During a study in Turkey, where recycling is still relatively rare and unknown, Ari E, et al. [11] obtained a self-named model, the Housewives’ Recycling Model, which could be used to explain housewives’ recycling behaviour: positive perceived behavioral control and surrounding social norms had a positive impact on guiding recycling behaviour, whereas attitude toward recycling did not statistically affect the recycling intention.

Mahmud S, et al. [12] investigated the precedent of recycling intention among secondary school students by using the basic TPB model. They also found perceived behavioral control to be the strongest predictor of recycling. However, subjective norm was also an important predictor of intention behaviour, but to a lesser degree. Meanwhile, attitude was an indirect predictor of intention behaviour, via the mediation of subjective norms and perceived behaviour control.

Despite the fact that there are many cogent research results by using TPB within disposal behaviour, several researchers have argued the basic TPB model does not explain this particular behaviour accurately enough and have proposed alternative, extended frameworks with additional variables. Botetzagias, et al. [13] extended the TPB with moral norms and demographics. They found that perceived behavioral control was the most important predictor of recycling intention and moral norms have a larger effect on behavioral intention than attitude. Besides, the demographic characteristics and subjective norms were not significant predictors at all. Chen MF, et al. [14] also extended the TPB with moral norms, besides recycling consequences, while focusing on municipal solid waste management. They successfully adopted perceived lack of facilities as a moderator for behavioral intention. It showed that an individual’s attitude, subjective norms, moral norms, and recycling consequences positively affect consumers’ recycling intentions. However, they revealed that perceived behavioral control was not a significant predictor.

White KM, et al. [15] extended the basic TPB model with selfperception items and the personality factor conscientiousness. Self-perception, instead of conscientiousness, turned out to be a significant predictor of recycling intention, but not a determinant of the actual behaviour. Besides, attitude and subjective norm, but not perceived behavioral control, are also predictors of recycling intention. Ramayah T, et al. [16] found that environmental awareness had a significant impact on attitude. Subsequently, attitude and social norms significantly influenced behavioral intention.

In sum, previous research has provided evidence for the predictive value of the attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control, to explain intention to general household disposal. First evidence has also been found for a more specific form of household disposal, namely textile disposal behaviour. However, post-consumer textile disposal should be studied separately from other forms of disposal [17]. Besides, no study has investigated yet how current knowledge on recycling, awareness on the state of the textile industry and consumer’s personal norms influence consumer’s disposal behaviour.

The Present Study

The main aim of the current study is to test whether knowledge on recycling, awareness on the state of the textile industry and consumer’s personal norms regarding the disposal of textiles will positively influence consumer’s textile disposal behaviour. This study has extended the original TPB model with three additional variables (Figure 2):

Personal norm regarding textile recycling;

Awareness of the negative issues surrounding the textile industry;

Textile recycling knowledge (Figure 2).

Like previously mentioned, the main research topics on consumers’ clothing disposal and behaviour are divided into four major categories: destination of waste (disposal methods), motivation for choosing a specific method, reasons why the textile item is disposed of and demographics [2]. The present study covers all categories, except for demographics, by using an extended TPB framework. In doing so, we can focus on the influence of attitudes, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control and the external factors of the TPB model, on the intention to engage in textile disposal behaviour. To take all types of disposal methods into consideration, we separated the disposal intention into four categories: textile disposal in exchange for an incentive; textile disposal without an incentive; extending the lifespan of textiles; binning unwanted textiles between household waste.

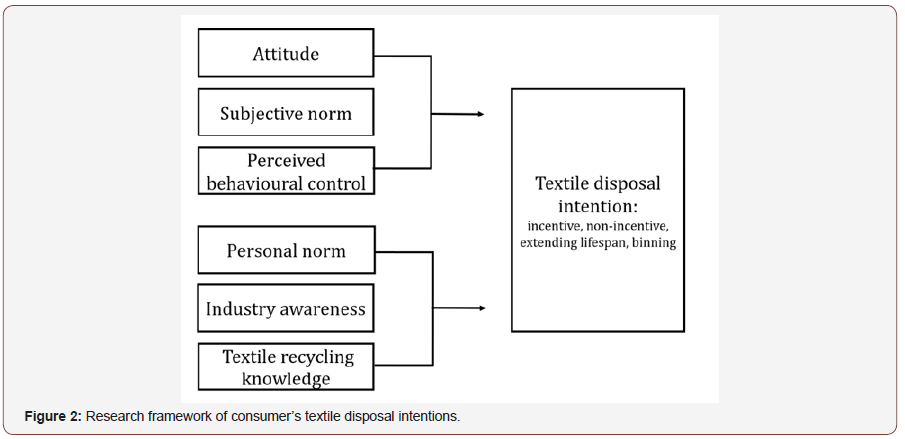

To establish a sufficient framework for the reuse and reduce of textile waste, we identified eleven textile disposal methods and three types of post-consumer recycling. Secondly, we identified three types of post-consumer textile recycling: yarn, fibre and polymer recycling. Combined with the Waste Hierarchy [18], a priority order of what constitutes as the best environmental option in waste treatment, they form the Textile Disposal Framework created to give a clear overview of the subject (Figure 3).

Following the assumptions of the theory, we expect a positive relation between the variables of the extended TPB and the four disposal intention categories.

Hypothesis 1:

The variables of the extended TPB model are significant predictors of the intention to dispose of textiles in exchange for an incentive.Hypothesis 2:

The variables of the extended TPB model are significant predictors of the intention to dispose of textiles without an incentive.Hypothesis 3:

The variables of the extended TPB model are significant predictors of the intention to extend the lifespan of textiles.Hypothesis 4:

The variables of the extended TPB model are significant predictors of the intention to bin unwanted textiles.Hypothesis 5:

The independent variables added to the original TPB model make a statistically significant contribution to consumer textile disposal intentions (Figure 4).Method

Sample

Data was collected in Flanders and the Netherlands by means of an online, self-report questionnaire survey in Qualtrics. The sample consisted of 491 respondents (77.2 percent female, 22.6 percent male, average age of 36.83, SD = 14.35, 40.9 percent Flemish, 56.6 percent Dutch). The sample was a convenience sample recruited via a researcher in charge of the data collection by using University email, industry network and social media. The necessary sample size (n) to apply our conclusion to a general population is 385, with a 95 percent confidence level, a 5 percent margin of error, a standard deviation of 0.5 and a population size of 23.000.000, which is approximately the total population of Flanders and the Netherlands.

Procedure

All survey respondents were informed about the subject. Their anonymity was guaranteed, and they were asked for their consent, before the start of the survey. Only if they agreed to participate, the online survey appeared. For those who did not agree, the survey ended. For all others, the survey started with a section of social-demographic questions, followed by the examination of the examines the original TPB variables: attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control. Next, they were questioned on the extended TPB variables: personal norm, industry awareness and textile recycling knowledge. Subsequently, we introduced the eleven textile disposal methods, questioned the respondents’ past experience and determined their familiarity with them. Next, the respondents had to indicate how many textile items they disposed of over the last year. Before the last phase of the survey, we introduced the four different disposal categories and connected them to the disposal methods: disposal in exchange for an incentive (take-back schemes, selling, swapping and temporary disposition); disposal without an incentive (donation, giving, textile bin and upcycling); extending the lifespan of textiles (keep and mending); and binning unwanted textiles between household waste (binning).

Instruments

A seven-point Likert-scale response format was used, from totally disagree, very unwilling or very unlikely

(1) to totally agree, very willing or very likely (7) and four as a neutral midpoint. If necessary, the items were recoded, so that the higher values indicated a positive stance towards the scales. The seven-point scale provides a wider range of stimuli and is therefore more accurate and easier to use. It leads to better decision making and is a better reflection of the respondent’s true evaluation, which may improve reliability and validity [19]. All instruments were translated from statistically significant scales from English to Dutch, if needed. We used Cronbach’s alpha in order to estimate the internal validity and reliability of our scales. Cronbach’s alpha is sensitive to the number of items in a certain scale. It is common to find low alphas on short scales (α<.5), with fewer than ten items. As all our scales are short, we will also report the mean inter- item correlation of items when the Cronbach’s alpha showed to be insufficient. Pallant J [20] recommends the optimal range of the inter-item correlation must lie between .2 and .420. Before administering the survey, a pilot study was carried out among a convenience sample of four males and six females to test in particular whether the survey questions were understood.

Attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control: The measurement scales of the TPB (attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control) adopted for this study, were validated in already existing scales developed by Davies J, et al. [21], Knussen C, et al. [22], Ramayah T, et al. [16], White KM, et al. [15], Ioannou T, et al. [23] and Oztekin C, et al. [24], who used TPB to examine consumer recycling intention. Some items were adapted to the requirements of textile recycling and all items were translated from English to Dutch. The attitude scale (ATT) has two items and showed a Cronbach’s alpha of .67, which is acceptable. The subjective norm scale (SBJN) also consists of two items and has an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α = .69). The perceived behavioral control scale (PBC) consists of four items and has good internal consistency (α = .77).

Personal norm, industry awareness and textile recycling knowledge: The scales composed for the extended part of our TPB model (personal norm, industry awareness and textile recycling knowledge) are based on validated items by Koch K, et al. [25], Davies J, et al. [21], Weber S, et al. [9] and our own items, using key elimination criteria for unnecessary items by Shimp and Sharma [26]. The personal norm scale (PRSN.NRM) consists of two items and showed good internal consistency (α =.76). The initial knowledge of recycling and knowledge of the fashion industry scales lacked internal consistency and where subjected to a principal component analysis with varimax rotation, to examine whether we had to create new. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) value was .67, exceeding the recommended value of .620 and Bartlett’s test of Sphericity was significant (p < .050). Using a scree plot, we kept a two-component solution with high factor loadings on both components (component one α = .62 and of component two α = .66). The two-component solution explained 33.2 percent of the total variance, against 21.3 percent of the one-component solution. We decided to use two separate scales, industry awareness (AW. TEX) and textile recycling knowledge (KNW.TR), instead of the two initial scales.

Textile disposal intention: We formulated six scenarios, including a corresponding picture, about different textile items: old socks, ripped sheets, a dress and a suit, a Hugo Boss shirt, jeans with a broken zipper and worn-out sneakers. The intention to dispose with incentive scale consists of five-items (α =.87); the intention to dispose without incentive (α = .76) consists of five items; the intention to extend lifespan scale consists of six items (α = .65) and the intention to bin scale has six-item (α =.76). Respondents had to indicate which of the disposal methods in the four intention categories they used in the last year. Lastly, we used the four intention categories to measure the respondents’ intention to engage in the four textile disposal categories. We set an explicit time frame, ‘over the next year’, to make sure all respondents considered the same time period [7]. The respondents had to indicate on a seven-point Likert-Scale how likely they were to dispose of the item in the coming year in all four disposal categories. During the survey termination respondents could fill in their email address if they were interested in the results of the study.

Data analysis

The collected data was analysed using SPSS version 24. We used different techniques such as descriptive statistics, scale reliability analysis, bivariate correlation, principal component analysis, hierarchical multiple regression and bootstrap regression. A Pearson product-moment correlation (r) was run to determine the relationship between the independent extended TPB variables and dependent intention variables. No assumptions were violated, and four outliers were deleted by means of the critical chi-square value and the maximum Mahal. Distance. Second, we used hierarchical multiple regression and bootstrap regression to determine the influence of the original and extended TPB variables on the level of intention to engage in the four different textile disposal categories

Results

On average respondents disposed of 27.49 pieces of unwanted textiles over the past year (SD = 21.16). 53.6 percent of the respondents was responsible for the disposal of their own textiles, 35.5 percent was also responsible for those of their family and only 10.8 percent was not responsible for their unwanted textiles at all.

Textile disposal in exchange for an incentive

67.4 percent of the respondents did not dispose part of their unwanted textiles in exchange for an incentive.

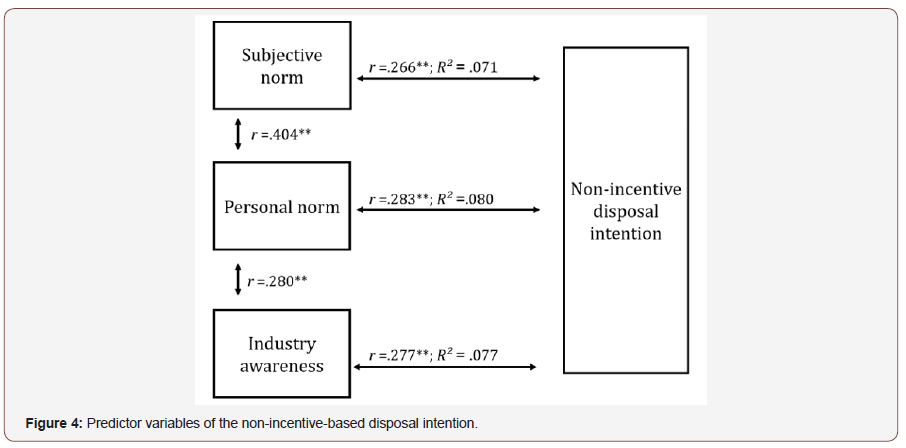

57.2 percent of the respondents are familiar with take-back schemes, but only 16.5 percent brought their unwanted textiles back to a store. 83.7 percent of the respondents know they can sell their unwanted wearable textiles but only 21.8 percent of the respondents actually sold some. Almost half of the respondents (48.7 percent) are familiar with swapping, but yet again a lot of less respondents took part in it over the last year: only 8.4 percent. This gap between knowledge of disposal method and past disposal behaviour also occurs with temporary disposition, where 26.5 percent of the respondents know it is a possibility but only 1.4 percent did it. This intention category has the lowest intention score of all the categories: 2.49 on a scale from zero to seven (strongly disagree to strongly agree). The intention to dispose of unwanted textiles in exchange for an incentive only significantly correlates with industry awareness (r = .09, p < .05), not with any of the other extended TPB variables. However, this correlation was very weak and does not influence the behavioral intention. Using a bootstrap regression, to remediate the violation of the normality and homoscedasticity assumption, the original TPB model explained 0.7 percent of the variance (R² = .007, p = .332), with none of the variables being a statistically significant predictor for the intention to dispose of unwanted textiles in exchange for an incentive. The extended TPB variables (R² = .021, p = .092) also do not make a statistically significant contribution to a higher intention level (p > .050). Therefore, the extended TPB framework is not a statistically significant predictor (F (6) = 1.66, p = .130) of the intention to dispose of unwanted textiles in exchange for anincentive (Figure 4).

Textile disposal without an incentive

Only 6.1 percent of the respondents indicated they did not dispose part of their unwanted textiles without an incentive. Although 92.9 percent of the respondents are aware of the donation method, only 51.9 percent actually donated part of their unwanted textiles to good will. 60.7 percent of the respondents gave their unwanted textiles to friends, family or acquaintances, in contrast to a 95.9 percent familiarity. The gap between familiarity and the actual behaviour was smaller regarding the textile bin (94.5 percent versus 71.1 percent). Almost half of the respondents (48.4 percent) are familiar with upcycling, but only 13.4 percent used part of their unwanted textiles in the upcycling process. The average score on the intention to dispose of textiles without an incentive, achieved the highest intention score of all four categories: 3.94, on a scale from zero to seven. The perceived behavioral control scale correlates significantly with the intention to dispose of unwanted textiles without an incentive (r = .17, p < .01). This was surprising, as perceived behavioral control was not a significant predictor of any of the intention variables, both in the original and the extended framework. The original TPB variables explained 9.7 percent of the variance (R² = .097, p <.050), with only attitude (p < .050, ß = .17) and subjective norm (p < .050, ß = .19) being significant variables. The extended TPB framework (R² = .140, p < .050), predicting the intention to engage in textile disposal without an incentive was a statistically more significant predictor than the original TPB framework (F (6) = 12.832, p < .050). Three main variables are significant predictors of the intention to dispose of unwanted textiles without an incentive: subjective norm (p = .006, ß =.15), personal norm (p = .007, ß = .14) and industry awareness (p = .001, ß = .16) (Figure 4).

Extending the lifespan of textiles

Only 14.3 percent of the respondents indicated they did not extend the lifespan of their textiles. 307 out of the 491 respondents (62.5 percent) did extend the lifespan of their textiles through mending, whilst 82.5 percent was familiar with it. 83.7 percent of respondents know they can keep some of their unwanted textiles in case they may end up being useful or back in style again, 60.5 percent actually did that. The average intention to extend the lifespan of textiles score has the second highest intention score: 3.60, on a scale from zero to seven. The original TPB model explained 2.7 percent of the variance (R² = .027, p = .004), with only attitude being a significant variable (p = .003, ß = .14). The variance explained by the extended TPB model was 4.2 percent (R² = .042, p = .073), with attitude being the only significant variable (p = 010, ß =.15). However, overall, the extended TPB was a statistically insignificant predictor (p = .073) of the intention to extend the lifespan of textiles.

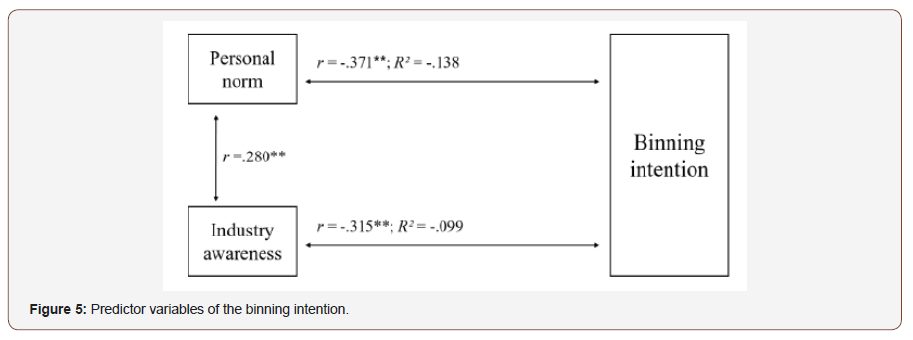

Disposal of unwanted textiles between household waste

79.4 percent of the respondents indicated they are familiar with binning and almost all of them (71.3 percent) said they threw part of their unwanted textiles between household waste for various reasons. A little over half of all respondents (50.7 percent) said they binned their unwanted textiles, because they are in such a bad state that no one can wear or use them again. This was followed by 193 respondents (39.3 percent) who think there is no other option for their old socks, underwear or tights. 10.2 percent (50 respondents) feel like other options cost a lot of effort and are timeconsuming, for them binning is the easy way out. 39 respondents (7.9 percent) want to get rid of their unwanted textiles immediately, 3.5 percent feels like their unwanted textiles have no value and are out of fashion. Only 1.4 percent thinks there is no other option (7 respondents) and .4 percent (2 respondents) indicated they don’t want anyone else using or wearing their unwanted textiles. The average binning intention score is 3.56, which is almost as high as the average score on the intention to extend the lifespan of textiles. The gap between knowledge of disposal method and past disposal behaviour, which occurs at all the other intention categories, does not occur at the intention to bin unwanted textiles. The perceived behavioral control scale correlates significantly with the intention to bin unwanted textiles (r = -.15, p < .01). Again, this was surprising, as perceived behavioral control was not a significant predictor of any of the intention variables. The original TPB model explained 12.2 percent of the variance (R² = .122, p < .050). The total variance explained by the extended TPB framework was 21.0 percent (R² = .210, p < .050). The framework predicting the intention to bin textiles between household waste was statistically significant (F (6) = 21.01, p < .050). Two main variables are statistically significant predictors of the intention to bin unwanted textiles: personal norm (p < .050, ß = -.22) and industry awareness (p < .050, ß = -.22), (Figure 5). Attitude and subjective norm are significant in the original TPB model, but do not remain significant in the extended TPB framework.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to test whether the variables of the extended TPB framework positively influence consumer’s textile disposal behaviour. Our results indicated that there is a gap between knowledge on the disposal method, previous behaviour and intention. In addition, it showed that subjective norm, personal norm and industry awareness all have a positive influence on the intention to dispose without incentive, while personal norm and industry awareness have a negative influence on the intention to bin unwanted textiles between household waste. The variables are insignificant predictors of the intention to dispose of textiles in exchange for an incentive and the intention to extend the lifespan of textiles. The intention to dispose in exchange for an incentive has the lowest intention score.

Increasing consumer participation in textile disposal in exchange for an incentive

This intention category had the lowest intention score of all categories and both the original and extended TPB variables are insignificant predictors of the intention. This is surprising, as many brands and retailers start their own take-back schemes with an incentive-based nature and the basic ‘law of behaviour’ is thought to be that higher incentives, lead to higher performance and more effort [27]. However, the incentive should be large enough to compensate the needed consumer effort in engaging in a certain demanded behaviour. If not, the incentive could counteract. So, if the incentive for disposing textiles is not high enough to compensate the needed consumer effort, consumers could avoid these disposal methods and the incentive counteracts its purpose.

Increasing consumer participation in textile disposal without an incentive

Subjective-, personal norm and industry awareness are the positive behavioral drivers for the intention to dispose of textiles without an incentive: the more aware consumers are of the negative environmental and societal aspects of the textile industry, the more positive personal norms a consumer has regarding textile disposal. If textile disposal is looked upon as the norm instead of binning and if people believe their friends or family would approve of their textile disposal behaviour, people will consider textile disposal as the standard instead of binning. This influences subjective norm, which all together leads to an increase in the intention to dispose of textiles without the exchange of an incentive. While some researches declare that attitude is also a main predictor of recycle intention16, this was not the case with textile disposal without an incentive. Thus, the key to increasing consumer participation in textile disposal without an incentive is anticipating on industry awareness and appealing to the consumers’ subjective norms, which will both influence personal norm. This could be achieved by informing consumer through an informative campaign about the negative effects of textile waste and what they can do to change it. Besides, if messages and corresponding images like ‘my friends and I…, or ‘in my family we…’ are incorporated in the communication, the consumers’ subjective norm will be triggered and thereby increases their personal norm, which will lead to an increased positive intention.

Increasing consumer participation in extending the lifespan of textiles

Like Ramayah et al. (2012) [16], Stols [10] affirms the significance of attitude. The research showed that attitude was the strongest predictor of the intention to donate, to resell and to reuse. In contrary to Stols’ research outcome, attitude was only a significant predictor of the intention to extend the lifespan of textiles in the original TPB model and not in the extended TPB framework, as the extended variables are statistically insignificant predictors. The Waste Framework Directive (2008) classified the extending options (mending and keep) in the prevention of waste section [18]. However, we included them in the list of disposal methods. Therefore, it might be possible that different predictor variables, specifically targeting the prevention of textile waste instead, could make a statistically significant contribution to the intention to extend the lifespan of textiles.

Decreasing consumer participation in binning unwanted textiles

According to Botetzagias I, et al. [13] feelings of moral obligation or personal norms have a larger effect on the behavioral intention of general recycling than attitude. This was confirmed by our research as personal norm was a significant predictor of binning, while attitude was not. A positive personal norm decreases the intention to bin unwanted textiles between regular household waste. Industry awareness also negatively influences the intention to bin unwanted textiles between regular household waste. Industry awareness and personal norm showed a weak correlation (r = .280), it indicated that the more aware consumers are about the negative issues surrounding the textile industry, the higher their feelings of moral obligation or responsibility regarding textile disposal is and thus the lower their intention to bin. If the textile industry, governmental organizations or policy makers would anticipate on industry awareness and adapt their informative campaigns or communicative strategies to them, personal norm would increase, and the yearly amount of textile waste could decrease.

Remarkably, textile recycling knowledge was not a significant predictor of any of the behavioral intentions regarding textile disposal. This was also supported by the descriptive analysis which showed that there was a gap between familiarity with the eleven textile disposal methods and past behaviour. However, in addition the conclusion of Morgan [6], Pieters [8] determined that ability, consisting of recycling knowledge and habit, was one of the main determinants of disposal behaviour. Ekström KM, et al. [28] stated that besides focusing on environmental policy measures to change consumer textile disposal habits, we must also focus on increasing consumer knowledge of recycling and reuse. So, contrary to what previous research stated, this research showed that textile recycling knowledge is not a significant behavioral driver of the four textile disposal intention categories and that there is gap between knowledge, past behaviour and behavioral intention. Besides textiles recycling knowledge, perceived behavioral control was also a statistically insignificant predictor of the behavioral intentions regarding textile disposal. This was in line with previous findings [21,29] and can therefore be excluded from the TPB model in research on textile disposal behaviour.

Research limitations and suggestions for future research

Although this research was carefully prepared, we are aware of its limitations. First of all, we did not run a factor- or scale reliability analysis with the pretest results to detect items that threatened validity and reliability. We only started this process after the survey was terminated.

Second, the research sample was obtained by means of a convenience sample. This is a non- probability sampling technique; therefore, we were unable to control the representativeness of the sample. The lack of control may have led to a biased sample; therefore, the generalizability of the research results should be approached with caution. In addition, our sample consisted of an uneven gender distribution, which also may have led to a biased sample and influenced our research results. It would be interesting for future research to study this topic with an all-male sample. Especially because none of the previous studies concentrated on men’s textile disposal behaviour with an all-male sample [2].

Although we did question our respondents on their socio- and demographic characteristics, we did not use them in the analyses. We intended to test our hypotheses on the controlling or mediating effects of gender and age but decided against it in a later research stage. We would suggest this step for future research, as gender, age or other socio-demographic characteristics might influence the behavioral intention regarding textile disposal practices.

We did not question the respondents’ proximity to the eleven textile disposal options. We are aware of the fact that for some of these methods’ availability is still very low [2]. This could be an explanation for the gap between knowledge, past experience and intention for some of the disposal methods such as swapping or temporary disposition. Other explanations could be the kind of incentive offered, the needed consumer effort (high and low) or the kind of textile that is disposed of. The knowledge-behaviour gap which occurred at multiple disposal methods would be an interesting topic for future research.

It was remarkable to see that the variables of the original and extended TPB framework are statistically insignificant predictors of the intention to engage in textile disposal in exchange for an incentive. As previously mentioned, an incentive could counteract the intended behaviour if the incentive is disproportionate to the effort needed to engage in a certain behaviour [27]. The incentive needed to activate consumers to engage in textile disposal would be a very interesting topic for future research.

Besides, our research showed that the intention to extend the lifespan of textiles might have different predictor variables then the ones we included in the extended TPB. We already stated that extending the lifespan of textiles falls in the prevention of waste section of the Waste Hierarchy18. This suggest that extending the lifespan of textiles should not have been categorized within the eleven disposal methods but should have formed a separate prevention of disposal list. Studying the prevention of post- consumer textile disposal and the behavioral drivers of its prevention options, such as keep and mending, is also a suggestion for future research.

Conclusion

There are many benefits and opportunities in reducing textile waste. However, if the industry and its consumers continue their current pace, textile waste will increase by 61 percent in in 2030 [30]. This research is therefore not only relevant for the academic world, but also for the textile industry and governmental agencies. The results point out that the four behavioral intention categories regarding the disposal of textiles have different behavioral drivers and are therefore in need of separate consumer strategies. Besides, this research made two theoretical contributions to the usage of the TPB in the field of post- consumer textile disposal. Perceived behavioral control was not a statistically significant predictor of any of the behavioral intentions and therefore not for the actual textile disposal behaviour. This suggest that perceived behavioral control could be excluded from the TPB model in research on textile disposal behaviour. Lastly, for some intention categories the original TPB variables are significant in the original model, but do not remain statistically significant in the extended TPB framework. Attitude was a significant predictor for the intention to dispose of textiles without an incentive in the original TPB model, but not in the extended version. Both attitude and subjective norm were significant predictors of the intention to bin unwanted textiles in the original TPB model, but do not remain statistically significant in the extended TPB framework. We would therefore argue that, while studying consumer textile disposal by means of the TPB, an extended TPB is a better research model than the original TPB.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- OVAM (2017) Textile sorting guide.

- Laitala K (2014) Consumers’ clothing disposal behaviour – a synthesis of research results. International Journal of Consumer Studies 38(5): 444-457.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017) A new textiles economy: redesigning fashion’s future.

- Eurostat (2014) Generation of waste by waste category, hazardousness and NACE Rev. 2 activity.

- European Parliamentary Research Center (EPRS) (2019) Environmental impact of the textile and clothing industry. What consumers need to know.

- Morgan LR, Birtwistle G (2009) An investigation of young fashion consumers’ disposal habits. International Journal of Consumer Studies 33(2): 190-198.

- Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50(2): 179-211.

- Pieters RG (1991) Changing Garbage Disposal Patterns of Consumers: Motivation, Ability, and Performance. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 10(2): 59-76.

- Weber S, Lynes J, Young SB (2017) Fashion interest as a driver for consumer textile waste management: reuse, recycle or disposal. International Journal of Consumer Studies 41(2): 207-215.

- Stols M (2017) The influence of pro-environmental motivation and intent on female consumers' apparel disposal behaviour (Master’s thesis). Consumer Science, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

- Arı E, Yilmaz V (2016) A proposed structural model for housewives' recycling behavior: A case study from Turkey. Ecological Economics 129: 132-142.

- Mahmud S, Osman K (2010) The determinants of recycling intention behavior among the Malaysian school students: an application of theory of planned behaviour. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 9: 119-124.

- Botetzagias I, Dima A, Malesios C (2014) Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior in the context of recycling: The role of moral norms and of demographic predictors. Resources Conservation and Recycling 95: 58-67.

- Chen MF, Tung PJ (2010) The Moderating Effect of Perceived Lack of Facilities on Consumers’ Recycling Intentions. Environment and Behavior 42(6): 824-844.

- White KM, Hyde MK (2012) The role of self-perceptions in the prediction of household recycling behavior in Australia. Environment and Behavior 44(6): 785-799.

- Ramayah T, Chow Lee JW, Lim S (2012) Sustaining the environment through recycling: an empirical study. Journal of environmental management 102: 141-147.

- Shim S (1995) Environmentalism and consumers’ clothing disposal patterns: an exploratory study. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 13(1): 38-48.

- Waste Framework Directive (2008) Directive 2008/98/EC on waste.

- Finstad K (2010) Response Interpolation and Scale Sensitivity: Evidence Against 5-Point Scales. Journal of Usability Studies 5(3): 104-110.

- Pallant J (2011) SPSS Survival manual. A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS (4th edn) Crow’s Nest: Allen & Unwin.

- Davies J, Foxal G, Pallister J (2002) Beyond the intention–behaviour mythology. An integrated model of recycling. Marketing Theory 2(1): 29-113.

- Knussen C, Yule F, MacKenzie J, Wells M (2004) An analysis of intentions to recycle household waste: The roles of past behaviour, perceived habit, and perceived lack of facilities. Journal of Environmental Psychology 24(2): 237-246.

- Ioannou T, Zampetakis L, Lasaridi K (2013) Psychological determinants of household recycling intention in the context of the theory of planned behavior. Fresenius Environmental Bulletin 22(7): 2035-2041.

- Oztekin C, Teksöz G, Pamuk S, Sahin E, Kilic DS (2017) Gender perspective on the factors predicting recycling behavior: Implications from the theory of planned behaviour. Waste Management 62: 290-302.

- Koch K, Domina T (1997) The effects of environmental attitude and fashion opinion leadership on textile recycling in the US. Journal of Consumer Studies and Home Economics 21(1): 1-17.

- Alvarado-Herrera A, Bigne E, Aldas-Manzano J, Curras-Perez R (2017) A Scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility Following the Sustainable Development Paradigm. Journal of Business Ethics 140(2): 243-262.

- Gneezy U, Meier S, Rey-Biel P (2011) When and Why Incentives (Don’t) Work to Modify Behavior. Journal of Economic Perspectives 25(4): 191-210

- Ekström KM, Salomonson N (2014) Reuse and recycling of clothing and textiles – a network approach. Journal of Macromarketing 34(3): 383-399.

- Boldero J (1995) The Prediction of Household Recycling of Newspapers: The Role of Attitudes, Intentions and Situational Factors. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 25(5): 440-462.

- (2017) Global Fashion Agenda and The Boston Consulting Group, Inc. Pulse of the fashion industry.

-

Rozanne Henzen, Dr. Sara Pabian. Increasing Consumer Participation in Textile Disposal Practices: Implications Derived from an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour on Four Types of Post-Consumer Textile Disposal. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech. 4(2): 2019. JTSFT. MS.ID.000581.

-

Textile disposal, Textile recycling, Textile waste, Theory of Planned Behaviour, Consumer behaviour, Recycling intention, Disposal Intention, Quantitative research

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.