Research Article

Research Article

Generational Cohort Comparisons of Fashion Disposal and Hoarding Behaviors

Hyun-Mee Joung*

School of Family and Consumer Sciences, Northern Illinois University, USA

Hyun-Mee Joung, School of Family and Consumer Sciences, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL, USA.

Received Date: October 01, 2021; Published Date: October 19, 2021

Abstract

The aim of this research was to compare post-purchase behaviors of fashion items focusing on participation in recycling, hoarding tendencies, keeping unworn items in the closet, and discarding among Millennials, Generation Xers, and Baby boomers. This study applied generational cohort theory to post- purchase behaviors of fashion items. A nationwide representative sample of U.S. consumers was used to collect data. A total of 443 respondents consisting of millennials (N=114), generation Xers (N=115), and baby boomers (N=214) completed a web-based survey questionnaire. MONOVA was used to compare participation in recycling, hoarding tendencies, keeping unworn fashion items in the closet, and discarding them among the three generations. Results revealed that millennials hoarded significantly more unwanted fashion items than generation Xers and baby boomers. Baby boomers participated significantly less in recycling than millennials and generation Xers. No significant mean differences were found in keeping unworn fashion items in the closet and discarding among the three generational cohorts. This study suggests that regardless of generational cohort memberships, the public media should educate consumers emphasizing the importance of recycling, featuring the recycling process and benefits. Marketing campaigns should promote consumers to participate in recycling. A fashion item is a semi-durable product that needs to be disposed of at the final stage of consumption. Although consumers are encouraged to participate in recycling to protect the environment, little attention is paid to fashion post-purchase behaviors. Comparing differences in participation in recycling, hoarding tendencies, and discarding behaviors among Millennials, Generation Xers, and Baby boomers is a new research area.

Keywords:Fashion disposal; Generational cohort; Hoarding; Post-purchase; Recycling

Introduction

A disposal behavior is the last step of consumption. After purchase and subsequent wear/use, consumers may no longer want their old fashion products (e.g., apparel, shoes, accessories) due to wear out, taste change, out of fashion, boredom, poor fit, etc. Jacoby, et al. developed a conceptual taxonomy of disposal options; 1) keep the product to extend the life of the product to serve the original purpose or to convert into a new purpose, 2) get rid of it permanently by discarding, donating, trading or reselling it, and 3) get rid of it temporarily by lending it [1]. The rate and length of fashion item usage before disposal is influenced by various personal factors (e.g., age, gender, attitudes, motivations) and product related factors such as fashion change, initial cost, quality, durability, and quantity [2]. It has been noted that an average lifetime of a cloth is approximately three years and five months [3]. How do consumers manage or get rid of unwanted old fashion items?

Consumers dispose of unwanted clothing through a variety of channels including donation, reuse, resale, pass-on, and discard. Researchers have identified factors that motivate and influence clothing disposal behaviors. Consumers resell unwanted clothing for economic gains, donate them for charity and environmental concerns, and throw them in a garbage can for convenience [4,5]. Previous research found that clothing disposal behaviors are influenced by environment attitudes, general recycling attitudes, and subjective norms of family members and friends [5-8].

Although previous researchers have identified clothing disposal methods and its influencing factors and motivations, there is still lack of understanding of fashion post-purchase behaviors. After a comprehensive review of clothing post-purchase behavior research, Laitala K [9] argued that studies on clothing disposal behaviors have reported inconsistent results and were limited to young college student samples with an overrepresentation of females. Laitala suggests that clothing disposal behavior needs additional studies focusing on heterogeneous samples including different demographic groups to generalize the finding [9]. Consumers in different age groups show different attitudes, interests, and activities, which affect consumption behavior [10]. This study applies generational cohort theory to better understand fashion disposal behaviors [11].

A generation cohort is a group of individuals who share similar cultural and historical experiences and unique common characteristics [12-14]. Consumers in different generations have different beliefs, values, and shopping behaviors [13]. Millennials are those who born between 1980 and 1996, are highly educated and defined as the first high-tech generation [14]. The millennial uses social media to interact with others and concerned about social responsibility and environmental issues [12]. Generation Xers are those born between 1965 and 1979 are highly educated and in the prime of their careers with high spending power [10,13,14]. Generation Xers are known as cynical and sophisticated about products and shopping. They purchase high quality products and are less influenced by fashion trends than millennials. Baby Boomers born between 1946 and 1964, are parents of millennials and have entered the retirement stage [13]. Baby boomers have a high level of education, are hard workers, and live in good economic times [10,13]. They influence others in consumption and trendsetting and are open-minded and willing to adopt new products/services [15]. Though it is believed that a generation is a strong determinant of post-purchase behaviors, virtually no study has compared postpurchase behaviors of fashion items among different generations. The aim of this research was to compare participation in recycling, hoarding tendencies, keeping unworn fashion items in the closet, and discarding them among Millennials, Generation Xers, and Baby boomers.

Review of Literature

A report indicates that though almost 100% textile wastes are recyclable, the average U.S. consumer throws away about 82 pounds of clothing and other textiles annually, and the waste makes up landfills [16,17]. In a study of fashion clothing disposal behaviors, Birtwistle and Moore note a throwaway fashion attitude is growing among the young fashion consumer [18]. Consumers throw away to get rid of unwanted clothing, because it is convenient, there is no recycling information available, and it saves time and energy to deliver it to a recycling center or station [4,7,9]. In a study of environmentalism and consumers’ clothing disposal patterns, Shim surveyed college students and found convenience-oriented discarding behavior is negatively related to environmental attitudes [5]. Further, researchers have identified reasons of why consumers throw away unwanted clothing. Consumers throw unwanted fashion items in the trash, if they are worn-out, damaged (stained/ holed/ripped) or not wearable by others [18-22]. In a focus group interview on clothing sustainable consumption, Goworek H, et al. [6] found that consumers perceived clothing that was cheap and made of low quality as ‘throwaway clothes’ and discarded it in the trash. Shim S [5] noted that clothing may be thrown away if the current value of the clothing is less than the current cost of the clothing or if the cost of keeping the garment exceeds the costs of disposing of the clothing. Norum PS [23] studied reasons of why consumers trashed clothing as a way of disposal and found that consumers discarded clothing that was too big or too small, no longer liked, going out of style, and no interest. Norum also reported that younger consumers threw away clothing much more than older consumers [23]. A discarding behavior is related to shopping orientation. Park, et al. studied influence of shopping orientation on discarding behaviors of fashion products and found that rational-oriented shoppers were less likely discard than hedonic oriented ones [8]. Previous research has also reported that discarding behavior is related to garment types such as underwear [20]. In a recent study, Norum PS [22] interviewed 24 females on why consumers use trash as a clothing disposal option and found that consumers threw underwear (panties and bras) in the trash due to intimate relationship of the garment to the body.

Consumers keep unwanted fashion items, even though they do not wear/use due to hoarding tendencies. Hoarding is defined as the “acquisition of, and failure to discard, possessions which appear to be useless or of limited value” [24]. It has been noted that on average, women wear 20-30 percent of their wardrobes, and others remain in the closet or are disposed of [25,26]. Although it has been suggested that any clothing that is not worn for a year should be disposed of, 21 percent of annual clothing purchases stay in the house [27]. A few studies have reported that why consumers keep, even though they do not ware clothing [18,28]. In a study of fastfashion post-purchase behavior, Joung [27] found that even though consumers did not wear or use, they liked to keep fashion items that had values; if fashion items were expensive, name brands, and made of high-quality materials (e.g., silk, wool, leather). Similar findings were reported in other studies; consumers were likely to keep expensive clothing that was rarely worn, because they felt guilty about disposing of them [18,22,30]. Bye E, et al. [28] studied why consumers keep clothes that do not fit. Results included that adult females kept unfitting garments, because they perceived weight management (“I keep thinking I’ll lose weight”), investment value (“I paid good money for it”), sentimental value (“It reminds me of a lovely time”), and aesthetic value (“I just really love it”). A hoarding tendency is also related to materialism. Joung studied college students’ clothing post-purchase behaviors and compared hoarding tendencies between materialists and non-materialists. Findings indicated that materialists hoarded more fashion items than non-materialists [29].

Consumers get rid of unwanted fashion products through participation in recycling such as donation to charities, passing-on to family members and friends, resale to second-hand stores, reuse for other purposes, swap with other consumers, and others. Koch K, et al. conducted a mail survey with a list of disposal options and asked how often consumers used each option. Findings indicated that the most frequently used disposal methods were donation to Salvation Army or Goodwill, followed bypass-on to family and friends, and used as rags [30]. Advantages or benefits of recycling are well documented [16,22,31]. Recycling reduces the need for landfill space, help others, save resources, and protects the environment. As noted earlier, nearly all textile items are recyclable; old fashion items recycled by donations are resold at charities’ secondhand stores and sent to developing countries. It has been noted that more than 70% of the world’s population uses secondhand clothing [32]. Old textiles can be also used as wiping cloths used in manufacturing industries and processing back into new fibers. In addition, recycling protects the environment. Most fabrics are made with dyes and chemicals that can contaminate the soil and water in the ground. Discarding textiles adds landfills; clothes can take up to 40 years to decompose [31]. Recycling textiles reduces the number of resources, such as water and chemicals needed, to produce new clothing. For example, it takes 700 gallons of water to make a cotton shirt and 1,800 gallons of water to make a pair of jeans [32].

Since environmentalism has become a key issue in businesses, organizations, and consumers, several researchers have studied clothing recycling behavior in conjunction with environmentalism [4,5,33-36]. These studies have consistently found a positive relationship between environmental attitudes and clothing recycling behaviors; consumers who are concerned about the environment are likely to participate in donation and reuse. In a similar study focusing on effects of environment awareness on disposal behaviors, Bianchi and Birtwistle compared consumers’ disposal behaviors of two countries, Scotland and Australia, and found that environmental awareness was related to clothing disposal behaviors of giving to family and friends in Austria, whereas it was related to donation to charities in Scotland [37]. Furthermore, attitudes toward general waste recycling (e.g. paper, glass, plastic, etc.) are strongly related to clothing disposing behaviors [5,37]. Morgan and Birtwistle [21] found that consumers who had habits of recycling glass, plastic, and paper were more likely to donate unwanted clothing to charities. This finding was confirmed with Goworek, et al. [4] that sustainable practices of existing habits and routines influenced clothing disposals.

A few studies have attempted to identify motivations for participation in recycling. For example, Ha- Brookshire and Hodge conducted in-depth interviews on used clothing donation behaviors and found that motivation for consumer donations of used clothing was related to a need to create space in the closet and to alleviate feelings of guilty that came from purchase clothing that was unworn and from past purchase mistakes [20]. Another study conducted by Joung and Park-Poaps focusing on consumer motivations for participation in recycling found that consumers resold unwanted clothing to second-hand stores for economic gain and environmental concern, donated them to charities for environmental concern, and reused them for economic gain [4]. Based on a review of literature, the study compared four aspects of post- purchase behaviors of unwanted fashion items among millennials, generation Xers, and baby boomers; 1) participation in recycling, 2) hoarding tendencies, 3) keeping unworn fashion items in the closet, and 4) discarding unwanted fashion items.

Methods

A self-administered web-based survey questionnaire was developed and contained four constructs of post-purchase behaviors including consumer’s hoarding tendency, participation in textile recycling, keeping unworn items in the closet, and number of fashion items discarding. For hoarding tendencies, seven items were adopted from previous studies and measured using a 7-point Likert type scale (1=strongly disagree; 7=strongly agree) [38-40]. An example of the item was that “I have problems with collecting fashion items.” For participation in textile recycling, six different options [4] were adopted and measured using a 7-point Likert type scale (1=never, 7=always). The six recycling options are 1) swap with family members and friends, 2) use recycling Websites (e.g., freecycle.org) to make available to others for free, 3) reuse for other purposes, 4) pass-on to family members and friends, 5) resale through consignment shops/eBay/garage or yard sales, and 6) drop-off to clothing/shoe collection bins to be used for other purposes. Two questions asked to indicate percentage of unworn fashion items in the closet in the past year and number of fashion items discarding in a year approximately. The questionnaire also contained questions asking how much was spent on fashion items and demographic information. Prior to collecting data, the survey questionnaire was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the researcher’s university.

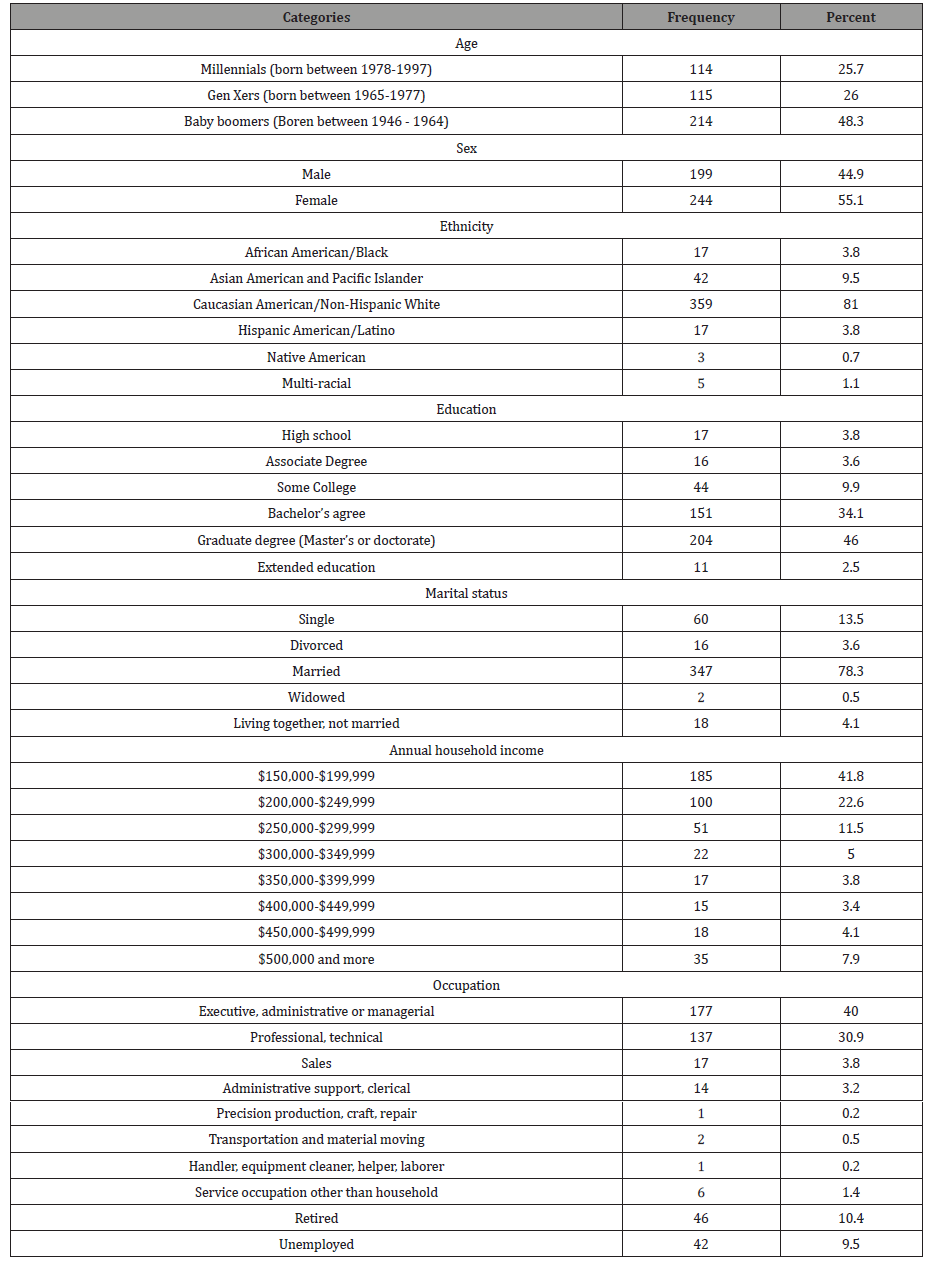

A nationwide representative sample whose annual household income was $150,000 or more was purchased from a sampling company. This study used high income consumers. It is believed that high income consumers have a large disposable income, which leads them purchasing more fashion items and being engaged in more disposals than other consumer groups [22,41]. A total of 443 respondents (199 males and 244 females) completed the online survey. For data analysis, IBM SPSS statistics 24 was utilized and a summary of the sample is presented in Table 1. The majority of the respondents were Caucasian (81.9%) and married (78%), had bachelor’s or graduate degrees (80%) and an annual income ranging from $150,000 to $249,999 (64.4%), and worked in executive, administrative, managerial, or professional fields (70.9%). On average, the respondent spent $2,000 -$2,500 on fashion items.

Table 1:Demographics of the Sample (N=443).

Results

Construct validity and reliability tests

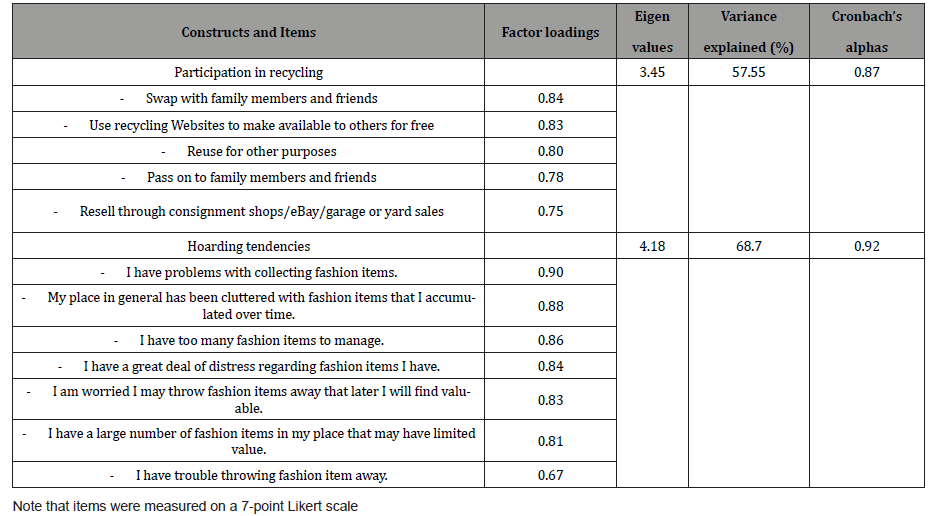

Principal Components Factor Analysis with Varimax rotation was employed on multi-items measuring the two constructs: participation in recycling and hoarding tendencies. Cronbach’s coefficient alpha was calculated to measure internal consistency of item loadings. A minimally acceptable reliability for the study was established at .70. A summary of the factor analysis with Cronbach’s alphas is presented in Table 2. For participation in recycling, of all six items, five were loaded on a single factor with scores ranging from .84 to .75, which accounted for 57.55% of the total variance. An item asking for dropping off fashion products to clothing and/ or shoe collection bins to be used for other purposes was excluded for further analysis. A coefficient alpha for the five items was .87, indicating acceptability. After the five items were summed and averaged, it is labeled as “participation in recycling.” Results of a factor analysis on hoarding tendencies indicated that all six items were loaded on a single factor with scores ranging from .90 to .67, which accounted for 68.70% of the total variance. A coefficient alpha for the six items was .92, indicating acceptability. After all items were summed and averaged, it is labeled as “hoarding tendencies”.

Table 2:Results of factor analyses of research constructs.

Descriptive statistics were conducted to summarize the constructs. The results showed that, overall, lower mean scores on hoarding tendencies (M = 3.12) and participation in recycling (M = 3.10) on a 7-point scale. On average, the respondents discarded about 10 fashion items per year and kept 20% - 30% of unworn old fashion items in their closet.

Group comparison analyses

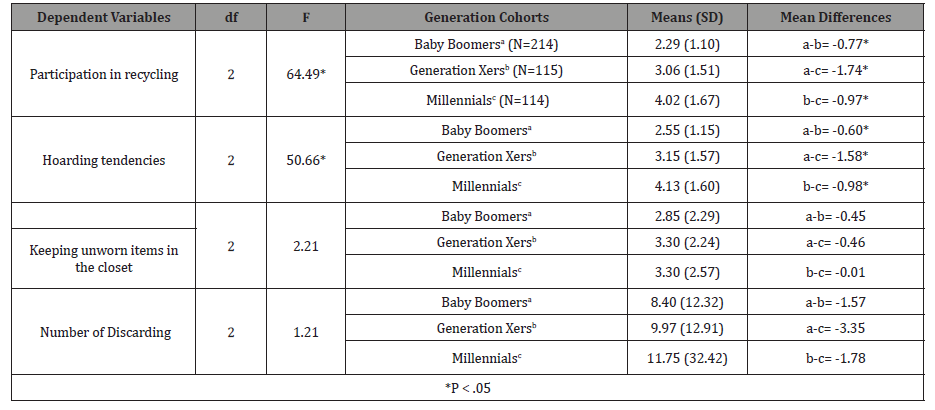

The sample were divided into three groups for further analyses: Millennials (N=114), Generation Xers (N=115), and Baby Boomers (N=214). Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was employed to compare differences in participation in recycling, hoarding tendencies, percent of keeping unworn fashion items in the closet, and numbers of fashion items discarding among the three groups. Table 3 summarizes findings. Statistically significant mean differences were found in hoarding tendencies (F= 50.66, p < .001) and participation in recycling (F=64.49, p < .001), whereas no differences were found in percent of keeping unworn items in the closet numbers and number of discarding fashion items among the three groups.

Table 3:Results of factor analyses of research constructs.

Post-hoc analyses using Scheffe test revealed that Baby Boomers exhibited a statistically lower mean score on hoarding tendencies than Millennials (ΔX baby boomer-millennials = -1.58, p < .05) and Generation Xers did (ΔX baby boomer-generation xers = -.60, p < .05). Generation Xers had a lower score on hoarding tendencies than Millennials did (ΔX generation xers -millennials = -.98, p < .05). For participation in recycling, Baby Boomers showed a statistically lower mean score than Millennials (ΔX baby boomermillennials = -1.74, p < .05) and Generation Xers did (ΔX baby boomer-generation xers = -.77, p < .05). Generation Xers had a lower score on participation in recycling than millennials did (ΔX generation xers -millennials = -.97, p < .05).

Conclusions and Implications

A fashion item is a semi-durable product that needs to be disposed of at the final stage of consumption. Little research has focused on how consumers to get rid of unwanted fashion items. This study applied generation cohort theory to post-purchase behaviors of fashion items and compared participation in recycling, hoarding tendencies, percent of keeping unworn fashion items in the closet, and number of discarding fashion items among millennials, generation Xers, and baby boomers.

Millennials showed a higher level of hoarding tendencies than generation Xers and baby boomers did. This may be related to fashion purchases. Millennials are trendy seekers who purchase more fashion items than generation Xers and baby boomers. However, an interesting finding was that baby boomers participated significantly less in recycling than generation Xers and millennials did. This was inconsistent with a previous study that older adults, aged 45-64 years, were more likely to participate in textile recycling [30]. An additional study focusing on baby boomers may be warranted. A future study should examine consumer knowledge of recycling regarding benefits and how/where to dispose of their unwanted fashion items.

Note that, overall, regardless of the generations, the respondents showed a high level of discarding behavior; they threw away about 10 fashion items per year. A similar finding was reported in Norum’s study [23] that one-third of the sample used trash as a clothing disposal method [23]. This discarding behavior could be related to lack of knowledge and information on how important recycling is. In an earlier, Domina and Koch noted that consumers are unaware of the need for clothing recycling and lack of knowledge of how and where clothing was disposed of [7]. Education is needed to make sustainable consumption. In a study of effects of education on recycling behaviors, Stall-Meadows and Goudeau surveyed consumers’ recycling behaviors before and after education and found that education changed consumer attitudes toward recycling; after the education, donating unwanted clothing to church or charities became the most preferred option and throwing in the trash became the least desirable option [42]. The public media and communities should actively educate consumers and promote participation in recycling featuring the recycling process and benefits of textile recycling such as helping others, saving materials/energy, protecting the environment and so on.

The fashion retailer/brand manager should promote consumers by offering incentives such as discount coupons. According to Jacobs and Bailey, any type of incentive, especially monetary incentives, increases consumer recycling behavior [43]. Currently few retailers (e.g., Patagonia) have offered discount coupons when consumers bring back old fashion items. This practice should be implemented in nationwide fashion retail stores. A future study may examine consumer attitudes toward retailers/brands who promote consumers participated in recycling or collect their old fashion items.

It should note that this study has limitations and suggestions for future studies. This study used a sample of high-income consumers. Though it is believed that high income consumers purchase more fashion products, which lead more disposal behaviors than lower income families, lower income families also consume fashion products and engage in disposals. A similar study should focus on low-income consumers’ disposal behaviors. Another study may compare fashion post-purchase behaviors using other demographic characteristics such as different ethnicities/races, gender, and cultures to generalize the finding.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Jacoby J, Berning CK, Dietvorst TF (1977) What about disposition? The Journal of Marketing 41(2): 22-28.

- Winakor G (1969) The process of clothing consumption. Journal of Home Economics 61(8): 629-634.

- Fletcher K (2008) Sustainable Fashion and Textiles. Design Journeys London, UK.

- Joung HM, Park-Poaps H (2013) Factors motivating and influencing clothing disposal behavior. International Journal of Consumer Studies 37(1): 105-111.

- Shim S (1995) Environmentalism and consumers’ clothing disposal patterns: an exploratory study. Clothing & Textiles Research Journal 13(1) 38-48.

- Goworeck H, Fisher T, Copper T, Woodward S, Hiller A (2012) The sustainable clothing market: an evaluation of potential strategies for UK retailers. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 40(12): 935-955.

- Domina T, Koch K (2002) Convenience and frequency of recycling - implications for including textiles in curbside recycling programs. Environment and Behavior 34(2): 216-238.

- Park HH, Choo TG, Ku YS (2016) The influence of shopping orientation on difficulty discarding and disposal behavior of fashion products. Fashion and Textile Research Journal 18(6): 833-843.

- Laitala K (2014) Consumers' clothing disposal behaviour–a synthesis of research results. International Journal of Consumer Studies 38(5): 444-457.

- Schiffman LG, Wisenblit J (2019) Consumer Behavior (12th edn), Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA.

- Ryder NB (1965) The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. American Sociological Review 30(6): 843-861.

- Eastman J, Iyer R, Thomas SP (2013) The impact of status consumption on shopping styles: an exploratory look at the millennial generation. Marketing Management Journal 23(1): 57-73.

- Edmunds J, Turner B (2005) Global generations: social change in the twentieth century. Br J Sociol 56(4): 559-577.

- Norum PS (2003) Examination of generational differences in household apparel Expenditures. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 32(1): 52-75.

- Rahulan M, Troynikov O, Watson C, Janta M, Senner V (2015) Consumer behavior of generational cohorts for compression sportswear. Journal of Fashion Merchandising and Management 19(1): 87- 104.

- (2018) Council for Textile Recycling

- Hawley J (2001) Textile recycling: a system perspective.

- Birtwistle G, Moore CM (2007) Fashion clothing-where does it all end up? International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 35(3): 210-216.

- Ekström KM, Salomonson N (2014) Reuse and recycling of clothing and textiles-A network approach. Journal of Macromarketing, 34(3): 383-399.

- Ha-Brookshire JE, Hodges NN (2009) Socially responsible consumer behavior? Exploring used clothing donation behavior. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 27(3): 179-196.

- Morgan LR, Birtwistle G (2009) An investigation of young fashion consumers’ disposal habits. International Journal of Consumer Studies 33(2): 190-198.

- Norum PS (2017) Towards sustainable clothing disposition: exploring the consumer choice to use trash as a disposal option. Sustainability 9: 1-15.

- Norum PS (2015) Trash, charity, and secondhand stores; an empirical analysis of clothing disposition. Family and Consumer Science Research Journal 44: 21-36.

- Frost RO, Gross RC (1993) The hoarding of possessions. Behav Res Ther 31(4): 367-381.

- Joung HM (2013) Materialism and clothing post-purchase behaviors. Journal of Consumer Marketing 30(6): 530-537.

- Smith RA (2013) A closet filled with regrets. Wall Street Journal, D1.

- Claudio L (2007) Waste couture: environmental impact of the clothing industry. Environ Health Perspect 115(9): A448-A454.

- Bye E, McKinney E (2007) Sizing up the wardrobe-why we keep clothes that do not fit. Fashion Theory 11(4): 483-498.

- Joung HM (2014) Fast-fashion consumers’ post-purchase behaviors. International Journal of Retail & Distribution management, 42(8): 688-697.

- Koch K, Domina T (1999) Consumer textile recycling as a means of solid waste Reduction. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 28(1): 3-17.

- Hawley JM (2006) Digging for diamonds: a conceptual framework for understanding reclaimed textile products. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 24(3): 262-275.

- Planet Aid (2016) 8 little known facts about our clothing habits.

- Leblanc R (2018) The basics of textile recycling.

- Domina T, Koch K (1998) Environmental profiles of female apparel shoppers in the Midwest, USA. Journal of Consumer Studies and Home Economics 22(3): 147-161.

- Koch K, Domina T (1997) The effects of environmental attitude and fashion opinion leadership on textile recycling in the U.S. Journal of Consumer Studies and Home Economics 21(1): 1-17.

- Bianchi C, Birtwistle G (2011) Consumer clothing disposal behavior: a comparative Study. International Journal of Consumer Studies 36(3): 335-341.

- Yee LW, Hasnah H, Ramayah T (2016) Sustainability and philanthropic awareness in clothing disposal behavior among young Malaysian consumers. SAGE Open 6: 1-10.

- Frost RO, Hartl TL, Christian R, Williams N (1995) The value of possessions in compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther 33(8): 897-902.

- Frost GO, Kim H, Morris C, Bloss C, Murray-Close M, Steketee G (1998) Hoarding compulsive buying and reasons for saving. Behav Res Ther 36(7-8): 657-664.

- Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G (2007) An open trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther 45(7): 461–1470.

- Lang C, Armstrong CM, Bannon LA (2013) Drivers of clothing disposal in the US: an exploration of the role of personal attributes and behaviours infrequent disposal. Journal of Consumer Studies 37(6): 706-714.

- Stall-Meadows C, Goudeau C (2012) An unexplored direction in solid waste reduction: household textiles and clothing recycling. Journal of Extension: 50

- Jacobs HE, Bailey JS (1982) Evaluating participation in a residential recycling program. Journal of Environmental Systems 12: 141-152.

-

Hyun-Mee Joung. Generational Cohort Comparisons of Fashion Disposal and Hoarding Behaviors. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech 9(2): 2021. JTSFT.MS.ID.000710.

-

Fashion disposal, Generational cohort, Hoarding, Post-purchase, Recycling

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.