Opinion

Opinion

Design Drawing: Rapid Prototyping through the Design Process

Dr. Angela Finn*

School of Fashion and Textiles-Design, RMIT University, Australia

Dr. Angela Finn, School of Fashion and Textiles-Design, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia.

Received Date: June 01, 2020; Published Date: June 08, 2020

Abstract

In recent times the focus for designers has been to increasingly engage with technology to generate more realistic and highly finished graphic representations and even virtual reality [VF] simulations that reflect real-to-life versions of potential design outcomes. This paper explores the advantages of design drawing as a form of rapid prototyping. What might be lost as traditional design methods, such as design drawing, are replaced with the release of more accessible, less expensive, technological replacements? The concern for designers, and design education, should be the potential loss of tacit understandings that arise as a part of the traditional design process and the physical, hands-on environment of the studio. This paper argues that the excitement of seeing design ideas rendered in high-tech realism might be at the cost of leaner, more efficient design practice.

Keywords: Design; Drawing; Creative practice; Design education; Fashion design

Abreviation: VR – Virtual Reality; CAD – Computer Aided Design

Introduction

The continuing development of design software has been an exciting aspect of the design process and design communication over the past 30 years. The ability for designers to render their design ideas in full color, to print high quality illustrations and generate digital graphics on site was a game changer in the 1990s. More recently, the ability for design companies (and design students) to gain access to program suites such as Adobe Creative Suite through relative low-cost subscriptions has led to the use of design software becoming in-house for small to medium size businesses. At present, the evolution of the app is making high end graphics even easier to access. At the time of writing, an app is being promoted through social media channels and claims to change backgrounds on your images with a click of the button. The ability of the software to generate professional outcomes, for a fraction of the cost that would be involved in hiring a professional graphic designer, is seen by many as a great advantage for newer players in the market, particularly within fashion. However, there is little thought for what might be lost in adopting automated methods of representing design ideas. This is the topic for this paper and a question we should be asking as designers or indeed, as design educators: What is the value of methods such as sketching in a virtual, digital world?

Discussion

Essentially, within design disciplines and industry, the act of design drawing is to make a 2D representation of a potential outcome in order to produce it in 3D form. This is the method that has been gradually replaced with Computer Aided Design [CAD] equivalents since the 1980s; within fashion this was with programs such as those developed by Gerber Technologies™ to enable computer aided design illustration and patternmaking. In Architecture, Construction and Engineering, AutoCAD animation-delay to computerize traditional draftsmanship associated with these industries. The great investment in computer software during the time (the cost of purchasing software and hardware to set up CAD systems was very substantial during the period 1980s-1990s) was to enable reuse of elements within individual objects for new projects. For example: fashion companies would save individual pattern pieces by digitizing them as separate files that could be then formed into models. The pieces for a pocket might be used in 5 or 6 different styles. A marker (a printed map of where all the pattern pieces would be positioned) can be used again every time a style is cut, where before CAD the marker was made by tracing patterns onto paper that was placed on the top layer of fabric and was lost as the fabric was cut. While reuse is desirable, and a cost and resource saving achievement, the impact of these ‘advancements’ have not been evaluated in terms of the affect they may have on the design process and the quality of design outcomes. In fashion, this may even be connected to commentary that all fashion looks the same.

For centuries, the artist, designer, craftsman has used the method of mark-making to understand the world a little better and to generate ideas for innovations and inventions to make life easier. What we already know about maker knowledge is that a large part of this type of knowledge is Tacit Knowledge. Michael Polanyi explains this complex theory simply as ‘knowing more than we can tell’ [1]. The meaning for designers and makers is that there is more to making than the expert maker can explicitly explain [2]. We also know that the apprentice learns at the hand of the master because learning through doing is an essential aspect of mastering skill-based activities, especially achieving mastery within creative practices such as design. In Polanyi’s words: “By watching the master and emulating his efforts in the presence of his example, the apprentice unconsciously picks up the rules of the art, including those which are not explicitly known to the master himself” [1].The phenomenon is also accredited to the repeated action of undertaking a task so many times that the specifics of the action are lost. Polanyi explains this in several examples but most eloquently in his explanation of how we learn new things such as riding a bicycle in his article, The logic of Tacit Inference [3].

The generation of new knowledge is important in discussions of tacit knowledge. The act of repetition also, eventually, contributes to significant innovation within accepted processes. In the case of design, the practice itself (the repetition of the methods of design, aside from the design outcome) is how a practitioner may achieve expertise. Once a level of expertise is achieved, the mind can focus on the bigger questions: Why do we design this way? How can we improve the design or development processes? What would happen if (…)? These are some of the questions that experts can ask that artificial intelligence (at least for now) is not able to conceive. The practice for designers has traditionally been the sketch, the design drawing and repetitive drawing of the same design concept to ‘draw out’ any issues and resolve them before starting work on the first prototype. Polanyi [4] summarizes this aspect for designers by stating: “(...) to produce an object by following a precise prescription is a process of manufacture and not the creation of a work of art. And likewise, to acquire new knowledge by a prescribed manipulation is to make a survey and not a discovery [5].” By foregoing the traditional methods of design in fields such as fashion and accessory design, are we entering a period where all design becomes a survey of exciting fashion moments that have passed rather than generating new design narratives?

The idea that expert practice is achieved through an iterative and action-based process is now widely accepted. Schön was the first scholar to illuminate how expert practice is achieved within ‘the professions’ to write his theory of professional knowledge presented in his seminal book: The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action [6]. As design becomes democratized in our world of easily accessible information, what are the developing issues for design as a discipline and a practice? The question is, as digital tools become more widely used to generate design outcomes (such as sketches, diagrams and models) does the practice become linear and does the expertise develop in using the software rather than in the development of a quality design outcome? The idea of iterations being lost in the editing process is also being discussed in other creative fields such as creative writing and art, but what are the potential consequences for design practice?

The advantages of computer aided design and the emergence of ubiquitous design software (in the form of iPhone apps such as Snap Chat and Instagram) are obvious. Is it a matter of time before the ability to understand the processes of design itself becomes tacit knowledge? Before generational knowledge of design, and design processes is lost it is important to consider the real benefits of low-tech methods for design development and testing that have the potential to be less expensive and offer more successful design outcomes? The disadvantage of Computer Aided Design is that is reduces the design phase, or in the case of apps, eliminates it altogether. The advantage of ‘old school’ software like CAD and AutoCAD is to document design outcomes for potential future use. The new generation of applications, rising up via social media platforms in response to a world where everyone is a designer, is to achieve fast and dirty design without the life span that would reveal possible issues such as ability for integration or consideration of the potential risks or harm.

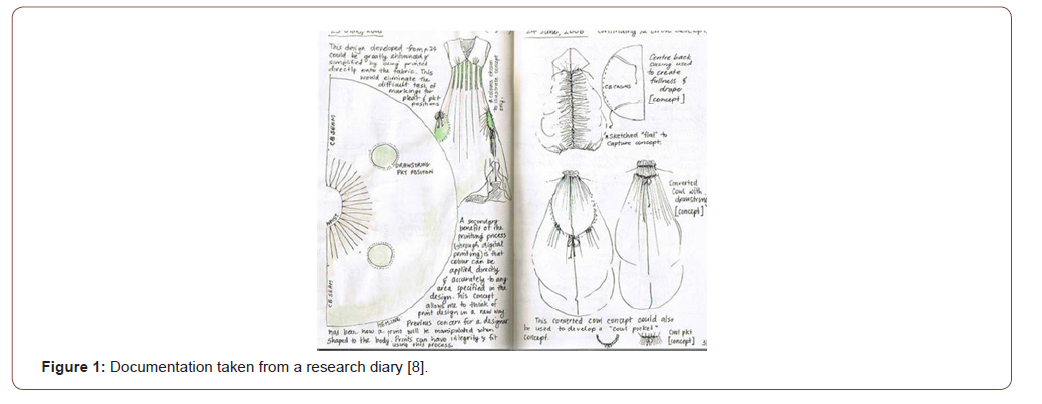

For designers, sketching is a method of both understanding and recording design ideas. The practice of creating sketches is not limited to recording details of the garments but is also a method of ‘seeing things’ as a designer or maker. These methods can be used to draw out forms of knowledge from the object, which may otherwise remain tacit, and also provide a means for deduction and speculation to occur from the perspective of the practitioner [7]. This is particularly relevant for developing fashion knowledge of design such as silhouette and proportion. The interpretation of a garment onto a figure through drawing captures the practitioner’s understanding of the design of the garment as it would relate to body and spatially. Figure 1 shows a page taken from a design journal. The drawing and journaling process becomes both a method of understanding the potential of a design concept but also a method of transferring knowledge of the design to other stakeholders. The sketch is able to record and communicate knowledge of the silhouette, the physical dimensions, the cut, the construction and the ‘feeling’ of the design. All of these factors form a part of fashion knowledge. However, the sketching process is also used to refine these aspects of the design, in respect of the designer’s expert and personal knowledge of fashion, design and make, in one stage of the design process – the design stage.

Reflection through replication or representation, the process behind creating a sketch, although largely tacit and intuitive, represents a deeper level of analysis than imagining or working with an initial idea. Drawings can be used to represent systems and processes as well as products themselves. Creating a digital sketch is a different process and experience. The action of ‘realizing’ a sketch using software is to focus on communication and accuracy rather than ‘play’ with a variety of options alternative solutions that might be more elegant, and better thought out, are likely missed if the process is not slower (and messier) than a version generated by computer. The use of the design drawing is a powerful tool to communicate design ideas quickly but also to bring teams into focus and provides an opportunity to discuss a way forward before committing to a plan of action too early in the design process. A quick sketch is ideal to communicate aims and goals for a project at a time where various stakeholders across the company can have an input into the design process.

Conclusion

For designers, who have been active within our disciplines in both industry and academia over the past 30 years, the digital revolution has been a rollercoaster, and one that was exciting to ride! The early CAD systems were such a life changing advancement for fashion design and graphic design in particular but as the technology has become more and more advanced, the potential impact on our knowledge of design, and the ability we have to use our process to eliminate potential problems and recognize the potential for one solution over another may be lost.

At the very least the technology can make the process longer and more arduous than putting pencil to paper and documenting design concepts and initial iterations using lean, low-tech, human centered methods. The physical documentation of design practice, and the use of design drawing and sketching to gain a deeper understanding of design concepts, also means that our ideas and ways of thinking – and our tacit understandings of design problems – might be preserved for future generations. Journals that survive the lives of great masters such Leonardo DaVinc. Such cases support the point being discussed here, that the value of a design journal full of hand-made drawings might as yet be unknown. The question for contemporary practitioners adopting digital documentation is: will future generations be able to see the reflection and development of your work in 500 years?

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Polanyi M (1962) Personal knowledge: towards a post-critical philosophy (2nd edn), London, England: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Polanyi M (1966) The tacit dimension. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Polanyi M (1966) The logic of tacit inference. Philosophy 41(155): 1-18.

- Polanyi M (1964) Science, Faith and Society. University of Chicago Press: Chicago & London, England, p. 96.

- Schon DA (1995) The new scholarship requires a new epistemology. Change 27(6): 26.

- Schön DA (1983) The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books, USA.

- Finn A (2014) Designing fashion: An exploration of practitioner research within the university environment. PhD thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Australia.

- Finn A (2008a) Black Moleskin Research Diary #1. Design Sketchbook/Research Diary. Brisbane/Auckland.

-

Angela Finn. Design Drawing: Rapid Prototyping through the Design Process. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech. 5(4): 2020. JTSFT.MS.ID.000620.

-

Design, Drawing, Creative practice, Design education, Fashion design

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.