Research Article

Research Article

Becoming the King’s Men – the Semiotic Molecule of Luxury Brand Heritage

Jan CL König*, Klaus-Peter Wiedmann, Janina Haase, Franziska Labenz and Nadine Hennigs

Leibniz University of Hannover, Germany

Jan CL König, Institute for Marketing and Management, Leibniz University of Hannover, Germany.

Received Date: June 09, 2020; Published Date: June 17, 2020

Abstract

In a spontaneous comparison, one might come to the conclusion that Savile Row shops sell real luxury, while on New Bond Street they simply sell expensive products. This conclusion includes reasons that can be understood by analyzing a typical traditional bespoke tailor shop with semiotic approaches. In our analysis, we applied Charles Peirce’s semiotic trichotomies to classify the signs of brand heritage, focusing on presented brand identities that appear in a structured construct that we call the molecule of the brand. Hence, the analysis leads to conclusions regarding what kind of signs produce a unique brand identity and how they refer to this identity concretely. Our findings offer a precise determination and evaluation of a luxury brand’s heritage management and presentation as well as a new understanding of heritage branding, the identity of brands, and the context in which they are created.

Keywords: Brand semiotics; Luxury brand management; Brand heritage; Brand identity; Luxury consumption; Myth; Framing

Introduction

London’s Savile Row is known worldwide for its bespoke tailors and hosts shops of traditional luxury [1], some of which can be regarded as being quietly legendary. Those shops are remarkable at creating an old-style luxury atmosphere using complex signs and textures to create a traditional luxury myth and address certain customers who identify themselves with the brand [2]. For the analysis of a luxury brand store with a traditional heritage, we apply a semiotic approach that eventually leads to a specific distinction of a unique brand heritage. Despite the increasing awareness of semiotic approaches in the marketing and management domains, current literature and case studies only use the surface of semiotics. We try to fill this gap and present a complex concept by applying the semiotic approach to the field of luxury brand management. Even though many different semiotic approaches exist, Charles S. Peirce’s philosophy is still one of the most complex, with three trichotomies and main subcategories, thus allowing for a precise analysis and a classification of meaningful significations. The design of a traditional luxury store was d to study the different simple and very complex structures of the sign meanings concerning the corporate culture of the luxury brand. Our results reveal the necessity of creating a traditional luxury store design using several complex and structured signs and meanings, including a narrative frame [3], thus leading to the myth of old-style luxury branding. With reference to the aforementioned concept of Peirce, our approach has the potential for further semiotic research not only for luxury fashion but also for several fields of marketing and management. Similarly, compiling a framework for brands with a traditional heritage must be a company’s core interest. Due to the compiled semiotic concept analyzing heritage framing, the implications of our study include advice regarding the use of signs for the creation of an elegant and old-fashioned atmosphere for luxury shops. The atmosphere of a luxury store can therefore represent the identity of a brand based on the specific meanings of signs. Nonetheless, the semiotic concept might also be a valid tool for further advertising or brand semiotics research in marketing and management.

Background

There is little consensus about the applied semiotic phenomena in luxury, although the semiotic concept seems to be an essential and inevitable part of luxury brand heritage. To have a better understanding of this phenomena, the principles of brand heritage from the luxury value perspective are discussed first and then followed by a brief introduction to Pierce’ semiotic philosophies, which will be the methodical background of our study.

Luxury values and brand heritage

The deep-rooted history of traditional craftsmanship in family business with well-known founding fathers is especially associated with luxury brands. It becomes evident that authenticity and emotions from the past represent relevant key elements of an advanced, well- positioned luxury brand, thus creating the core part of brand heritage. Urde M, et al. [4] define the heritage of luxury brands as “a dimension of a brand’s identity found in its track record, longevity, core values, use of symbols and particularly in an organizational belief that its history is important“. According to this, a brand with a strong heritage is assumed to be very genuine, dependable and trustworthy [5,6]. Regarding the wide range of the differentiation and authenticity due to the early roots, the heritage of luxury brands can be a significant value driver [7]. Through heritage, we can “define these brands today and add value, especially when they are re- interpreted in a contemporary light”. In the times of a fast-changing digital environment, luxury brands have to challenge the link between the past and the present in a way that is more meaningful, modern and history-charged [8].

As consumers are increasingly aware of a brand’s origin, the heritage of a luxury brand is an essential part of the relationship between the customer and the brand that is seeking the customer’s loyalty [9]. This also has effect on a brand’s shop architecture: “In a consumer-driven retail environment, brands seek to build strong customer relationships by providing dazzling stimuli […]” [10].

Existing research on the influence of brand heritage in the luxury industry found evidence for a causal relationship between brand heritage and brand luxury, as well as significant impacts on a customer’s perceived value and resulting effects on brand strength.

Indeed, a causal relationship can be observed between the brand, heritage, and luxury, as the impacts on perceived value and the effects on a brand’s strength are highly significant [11]. However, a luxury brand, which symbolizes and represents the customer´s lifestyle, is always required [12]. Overall, brand heritage may be regarded as one of the major components for building successful luxury brands, which is an assumption that leads to the creation of a sustainable unique brand personality, brand meaning, and core values and manifests in the tension between the past, present and future.

Semiotic approaches for the meaning of brand

The term semiotics is typically related to the antique Greek phrase of σημεῖον (semion), which means sign [13]. By deriving from an original phrase and referring to an academic concept, semiotics implies a specific meaning. Thus, the core characteristic of semiotics can be described and interpreted as the meaning of signs.

Unlike the traditional quantitative methods in marketing and management that imply the investigation of several stimuli and their effects, the qualitative semiotic approach examines the consistence and the creation of the stimuli – i.e., the signs. With representatives such as Charles Peirce in the early 20th century and Lévi-Strauss, Barthes, Eco, and Jakobson later on, semiotic studies in the humanities became very popular during the pragmatic turn. Many known disciplinary phrases in the humanities, especially the linguistic domain, have been influenced by the semiotic approach. Though there is a strong interest for marketing and management to identify the consistency and quality of signs for the creation of brands, semiotics was first recognized for marketing and management in the 1980s [14-17]. Nevertheless, quantitative approaches investigating stimulus-response models are the most commonly used, and the semiotic approach as a productive methodology has gained more importance in recent years [13,18- 26], as well as König, et al. [2] regarding luxury brand myths in reflection of Barthes’ approach). Nevertheless, “very few studies have focused on the concept of brand contract […], the discourse directly emitted by the brand, and the relevant methodology to analyse brand extendibility” [27].

Thus, there is a lack of studies investigating semiotics in the context of luxury marketing [28]. Starting from the ground, a differentiation between the trivial and the extraordinary luxury is of core interest in the field of luxury research. Though Vega-Sala/ Roux, et al. [27] and Kessou, et al. [29] did some prior research in this context before, there is much future research necessary.

Regarding the application of semiotics for marketing and management, we generally still have to face a methodological approach that is simplified to research markets, and concepts that are used to deal with simple numbers. Nevertheless, by starting with an approach that offers a broad range of differentiation, semiotics offers the possibility of introducing complex models for understanding the meaning of signs as creators of brand identity. Concerning the complexity of sign construction and its variables, Peirce’s model still may be regarded as the most differentiated and distinctive semiotic approach ever established [30,31]. While earlier semiotic marketing approaches and reflections only pay attention to the fact that signs represent specific meanings of brand, the adaption of Peirce’s classical model in the context of marketing offers the unique classification of what, where, and how signs create our reality. Within this trichotomy of signs that refer to brands in general and luxury in particular, we may observe the construct of how brand management can create values up to a unique and distinctive identity. “Brands are built over time and space. Since the day of their creation, brands shape and develop themselves. Their identity is created through successive communication campaigns year by year” [27].

Conceptualization and Propositions

Especially in the marketing and luxury industries, the signs of a brand identity can face consumers at any time. “The consumer world is a web of meanings among consumer and marketers from signs and symbols ensconced in their cultural space and time” [32]. Against this backdrop, the question arises as to what kind of consumers are confronted with signs, or more specifically, what kind of sign chains they associate with the brand. Based on a compilation of Peirce´s trichotomies, a conceptual framework, which we call the semiotic molecule, will be constituted. Finally, we will derive the propositions for the sign chains of luxury brand myths in terms of the aforementioned concept.

Defining the text: signs as textual phenomena

To determine the signs relating to luxury values, it should be realized that all the signs that are included in such a context can accumulate in a text that can be read. This holistic understanding of a text [33-35] simply relies on the assumption that we communicate with all of our senses. The sum of those signs creating a specific (up to complex) meaning in this way of communication can be defined as the semiotic text that consumers are able to read [36]. This idea can be exemplified by food in supermarkets, which is arranged as a textual sign chain with reference to specific values.

M&S [Marks & Spencer] utilize a style that defines the brand and values of the group, and in order to elevate the definition and significance of their food within the market, they adopt a modern approach to food marketing that utilizes a set of semiotic codes to reinforce and add symbolic value to their products [37].

Therefore, without neglecting other approaches of textual research, semiotic texts can be seen as multisensory complex sign chains, which is an assumption that builds the foundation for new approaches in future research. Concerning our observation and in favor of an easier intuition, only the visual signs will be brought into focus within the semiotic text.

Meaning of brand presentation: The semiotic molecule

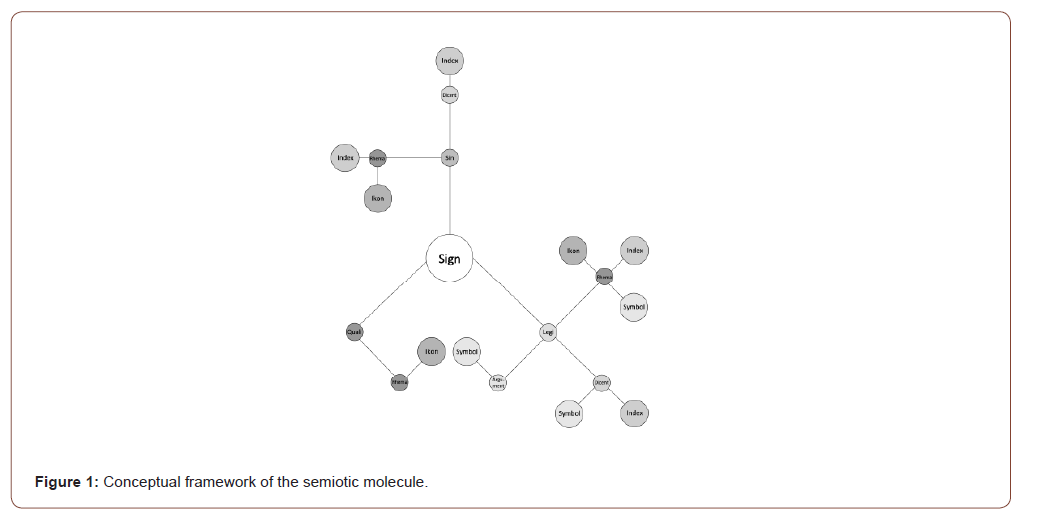

The semiotic approach of Charles Peirce offers the possibility to determine signs with a precision of three different perspectives concerning the Representamen, i.e., the relation of the Representamen to the signified object, and the relation between the sign and the Interpretant, i.e., the complexity of the sign for a reader. This trichotomy is divided into three different classes, which are Firstness (possibility), Secondness (existence), and thirdness (law). Representamen (which we will call signs in the following) may be divided into qualisigns, sinsigns, and legisigns, and object relations may be divided into icons (such as a statue or picture), indices (such as smoke referring to fire), or symbols (arbitrary signs). Interpretant relations may be divided into rhemas, dicents, and arguments, which represent the complexity of the meaning of a single word up to complex sign chains and systems [30,31,38]. Theoretically, these three trichotomies would result in 27 combinations (3x3x3), but due to some impossible combinations (a qualisign can only be rhematic and iconic), a total combination of ten main sign classes is possible. Within a semiotic framework, we call these ten possible combinations the semiotic molecule on which our world of signs is based (Figure 1).

The idea of a semiotic molecule of brands is also presented by Rossolatos G [39] and Santos FP [40], who compared a compilation of semiotic classifications with the structure of a molecule. This approach is related with a rather philosophical overview of brand construction rather than with textual brand creation. “Like a Gestalt, the wholeness of the elements and their dependent relationships shape the existence of a brand” [40]. Contrary to that approach, in our concept of a semiotic molecule, the combination of the trichotomies leads to paths in each specific main class. In a rather artistic illustration, the model appears to look indeed like a molecule. The core, representing a sign, is surrounded by the various possibilities, which eventually create specific classes and thus the qualities of signs (Figure 2).

Objectives of the semiotic approach

With reference to Peirce’s semiotic approach, two central issues will be addressed: first, the examination of the specific kinds of signs, and, second, the manner regarding how their consistence plays a role in value creation. Particularly with regard to the object relation and its representation to consumers, it is essential to investigate the following research questions:

RQ1: What signs are used to create a specific brand representation to customers?

RQ2: How do sign trichotomies refer to general luxury phenomena or an individual brand heritage?

Finally, using the example of a certain shop design, we will be able to conclude whether there is a relation to the brand’s identity, how this relation causes the brand to stand out from others, and what kinds of signs need to be set in order to accomplish such a communication of luxury brand heritage.

Semiotic Analysis of Luxury Brand Heritage and Myth

To get an idea of how a shop design can reflect luxury heritage and myth, the major phenomena and artifacts of an exemplary shop in London will be examined in the following sections. First, we will consider the possibilities of the aforementioned semiotic approaches to set a qualitative research method. Second, we will shortly introduce the company and its specific London quarter. Finally, the communicational artifacts that form the analyzed semiotic text will be determined. Having laid that groundwork, we will investigate the text according to Peirce’s trichotomies and, in this way, answer the stated research questions.

Semiotics as a method

Since the great semiotic scholars such as Barthes, Peirce, and others have constituted signs as philosophies (in terms of explaining phenomena with their specific linguistic approach), we will rely on their ideas and reversely apply them (similar to other linguistic approaches, such as rhetoric, which was actually developed to facilitate rather than to analyze effective speech). This procedure is well-established in linguistics and, therefore, can be assumed appropriate for a similar field of interest dealing with luxury marketing and management. The analysis concerning Peirce’s trichotomies will be presented in table form by only exhibiting relevant and exact matches.

No. 11 Savile row

The bespoke tailor Huntsman (H. Huntsman & Sons Ltd.) [41], which is located at No. 11 Savile Row, is one of the most traditional dressmakers in London and was established in 1849 [42]. Apart from its traditional English Savile Row tailoring [43-45] and its long heritage [46], the company is also famous for the luxury-seeking celebrities who have been purchasing their clothes at Huntsman for decades [47]. Consequently, the Huntsman shop at Savile Row, whose setup has hardly changed over the last century, provides an ideal instance to examine shop design, with reference to luxury and heritage, from a semiotic perspective.

Corpus: semiotic text of No. 11 Savile row

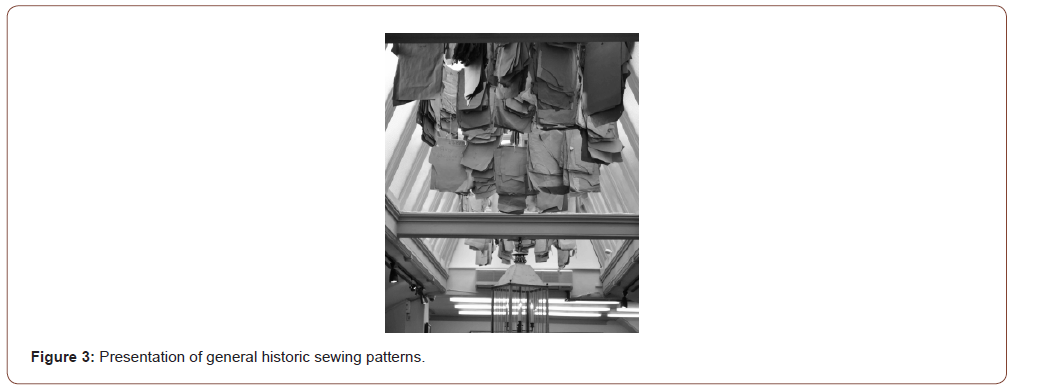

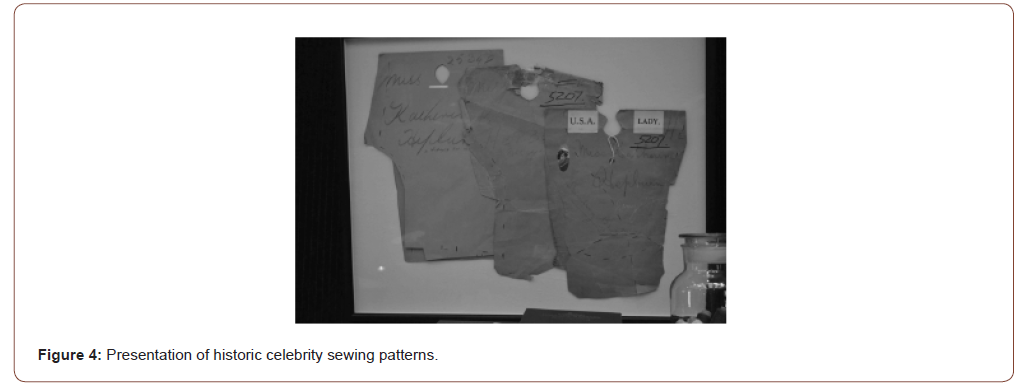

We chose five specific artifacts, or coherent presentations, that have a neutral position in the shop for our analysis. As communication is multisensory, all other communicational signs apart from the visual ones, which we concentrate on, had to be omitted. Thus, we will focus on the following items: the presentation of patterns for sewing (Figures 3&4) and of fabric samples (Figures 5 & 6), historical order books (Figure 7), old riding breeches in a glass cabinet (Figure 8), and, finally, double stag hunting trophies (Figure 9). To get a better impression of those sign components that cannot be read immediately, we additionally conducted an expert interview with Huntsman’s director of marketing and press.

Luxury brand molecules at No. 11 Savile row

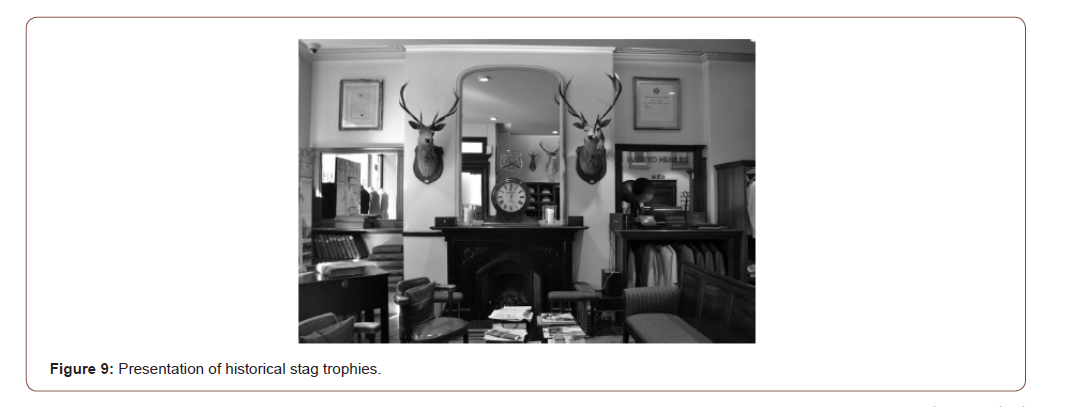

Our observation starts with the analysis of the historical sewing patterns presented in the shop (Figures 3 & 4). Patterns such as the ones presented are still in use today. We may distinguish between patterns in general and those of celebrities such as Gregory Peck and Katherine Hepburn. As a dicentic-indexical sinsign, individual sewing patterns present the long history of individual bespoke sewing. As a dicentic-indexical legisign, we find the signification of a long history of individual customer care. This leads into the meaning of the patterns as an argumentative-symbolic legisign representing Huntsman’s traditional craftsmanship for individual customers. By observing the specific celebrities’ patterns, this signified meaning changes. While specific celebrity patterns as a dicentic-indexical sinsign contain the signified representation of a specific prominent Huntsman customer, they also stand for Huntsman’s impressive historical celebrity customers and thus Huntsman’s luxury customers in general as an argumentativesymbolic legisign (Table 1).

Table 1:Semiotic Analytical Table – Historical Sewing Patterns.

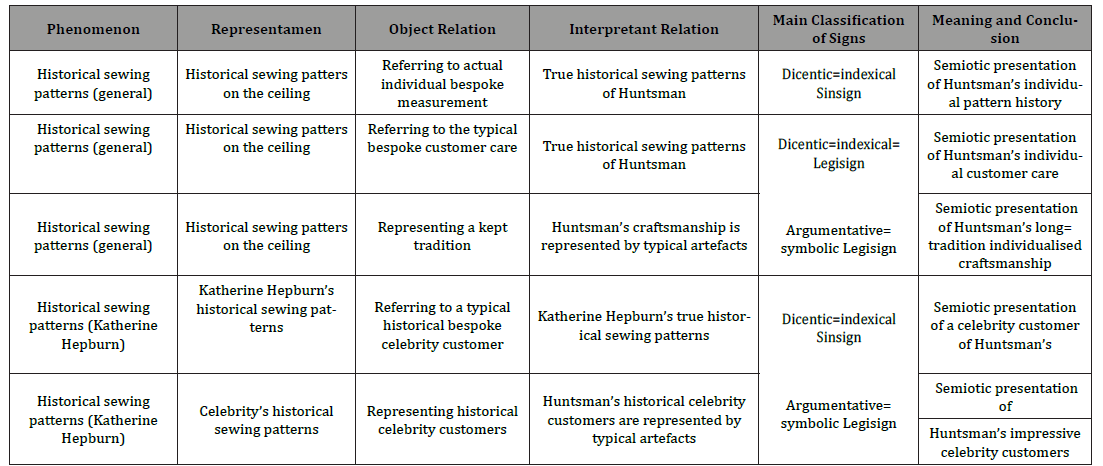

The second artifact presentation we chose for our analysis contains the fabric samples that can be observed in the shop either in (historical) sample books or as samples on a table (Figures 5 & 6). As a dicentic-indexical sinsign, we may regard the fabric samples on the table as a presentation of the specific luxury fabrics used at Huntsman. As a dicentic-indexical legisign, we may derive the meaning of fabrics that are typically luxury at Huntsman. Regarding the historical sample books, we found two different signified meanings. First, as a dicentic-indexical sign, the presentation stands for specific sustainable luxury fabrics that are used at Huntsman. Second, as an argumentative-symbolic legisign, the historical books represent the luxury and sustainability of materials that have been used at Huntsman consistently (Table 2).

Table 2:Semiotic Analytical Table – Presentation of Fabric Samples.

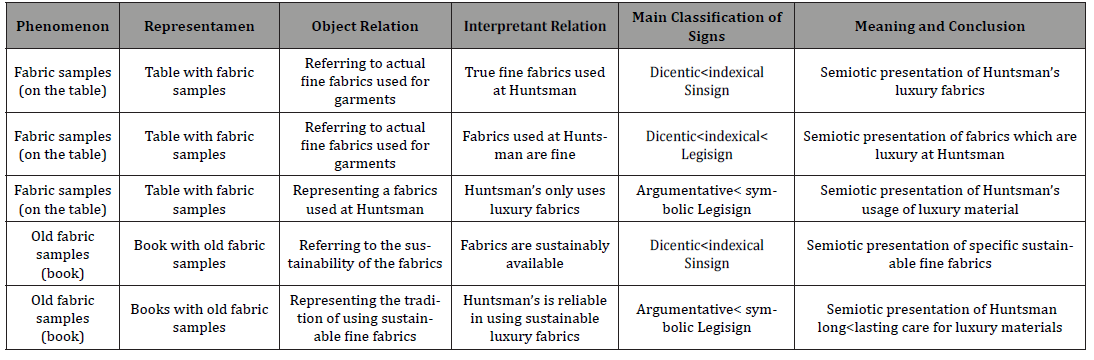

Our third selected artifacts in the shop are the historical order books (Figure 7). While today’s customers are recorded in a computer system, the order books had been used since the beginning of the company, and therefore for decades, for the filing of all customers. As a dicentic-indexical sinsign, we can derive that Huntsman has a long list of individual customers. Since some of them are famous, the books represent Huntsman as a tailor of luxury customers with a long tradition in general as an argumentativesymbolic legisign (Table 3).

Table 3:Semiotic Analytical Table – Order Books.

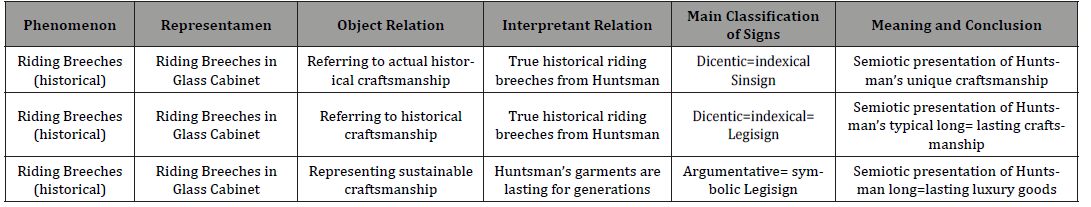

The fourth artifact can be observed immediately behind the cash register. It is a glass cabinet containing an old pair of riding breeches (Figure 8), which belonged to the son of the founder’s descendant who moved to Africa. The family returned in the late 20th century and gave the breeches back to Huntsman where they have been exhibited since. In the sense of a dicentic-indexical sinsign, we may expect the presentation of Huntsman’s unique craftsmanship regarding this one item. As a dicentic legisign, we can follow that Huntsman’s craftsmanship is typically long-lasting. As the most general signification, the breeches represent Hunstman’s extraordinary luxury quality in an argumentative-symbolic legisign (Table 4).

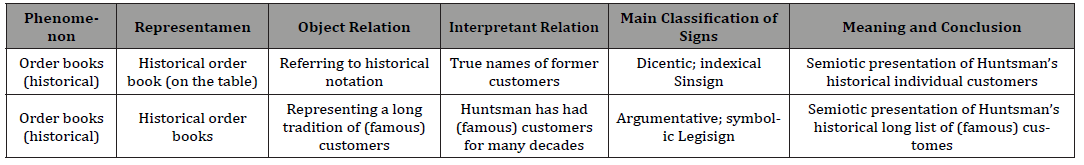

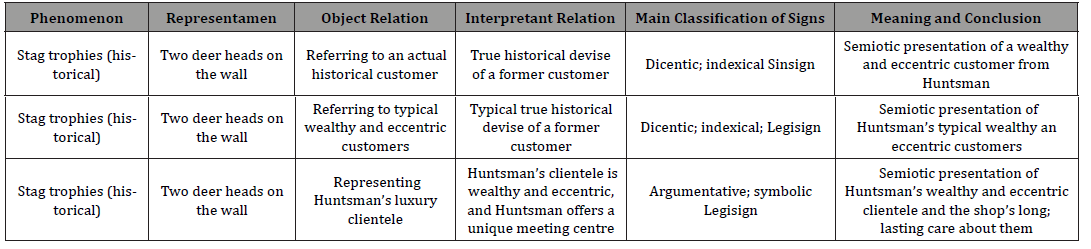

Our last examples for luxury semiotic signs at Huntsman are the double stag trophies in the shop’s front area (Figure 9). A previous Huntsman customer was obviously both quite wealthy and slightly eccentric, as the trophies as a dicentic-indexical sinsign represent. As a dicentic-indexical legisign, they refer to Huntsman’s typical wealthy and eccentric (or sophisticated) customers in general. Finally, the trophies create the final argumentative-symbolic legisign, thus representing Huntsman’s wealthy and eccentric clientele, as well as Huntsman’s own reliable customer care (Table 5).

Table 4:Semiotic Analytical Table – Riding Breeches in Glass Cabinet.

Table 5:Semiotic Analytical Table – Stag Trophies

Regarding our research questions, our analysis leads to the result that especially semiotic indices are used to create meanings of luxury, referring not only to luxury items in general but how they are represented by the brand specifically (RQ1). Those indices may appear as single examples (and are hence sinsigns) or also as a general reference to Huntsman’s craftsmanship, mainly in either the combination of dicentic-indexical sinsigns or dicentic-indexical legisigns (RQ1). They appear remarkably successful when they do not only refer to an event of the past, such as the order books, but when they link the individual luxury brand heritage with today’s craftsmanship, such as the fabric samples, sewing patterns, or stag trophies, regarding their reference to customer care (RQ2). In addition, by being general symbols of all three of Huntsman’s luxury craftsmanship, heritage, and customers, those artifacts signify argumentative-symbolic legisigns (RQ1). All signs refer to luxury items in general, as well as how they are represented by Huntsman specifically (RQ2). The individual brand heritage is represented with various individual artifacts that are linked to Huntsman’s history. Hence, they are not exchangeable but belong originally to Huntsman’s specific heritage (RQ2).

Discussion

Since the research questions have been answered and, thus, the underlying assumptions have been validated, the results prompt our discussion of the following question: What is the difference between a historical and a living (and therefore managed) heritage? This issue will be discussed in the following sections. Then, the limitations of this study and implications for future research are addressed.

Historical heritage vs. managed myth

Looking at the results, we can sum up that symbolic significations provide a broader frame and an explanation for the brand’s tradition, customers, and craftsmanship, while indexical significations support direct references to the brand’s actual culture. These findings lead to consequences that are important for sign presentations and combinations and that can be discussed with respect to the following examples.

From the perspective of luxury heritage, the represented sewing patterns are equal to their texture with the only exception being their affiliation. Most patterns belong or belonged to ordinary customers, while a few belonged to celebrities, such as Gregory Peck or Katherine Hepburn. Certainly, the latter is referred to as an index to Hollywood’s Golden Age and consequently as a symbol to Huntsman’s long tradition of high-class tailoring for the high society. Thus, such celebrity patterns are a representation of a glamorous consumer ship that Huntsman has been calling its own, but the question remains as to whether the reference counts only as a historical artifact. If so, this would lead to the conclusion that Huntsman refers indeed to its history but not its present, and it would create a myth referring to luxury only as a self- contained attribute or a relic kept behind glass. However, the major task for brand management is to build a bridge between the historical artifact and the lived present. Huntsman accomplishes this mission by presenting both celebrities’ and normal customers’ sewing patterns, as well as storing those of current customers in the back of the shop. This mission draws a perfect line between Huntsman’s heritage and its current daily luxury business, with signs having the same shape, material, and original usage that refer to the same luxury values. Hence, the referred-to tradition is alive, and the signified myth is not just a museum object but is an inherent part of Huntsman’s craftsmanship. Hence, according to Krappman’s theory of social identity by acting [48], the myth belongs to its brand identity. This coherent line is unsuccessfully created regarding the historical order books’ presentation. While the presentation indeed refers to Huntsman’s long tradition while all orders are filed in a computer system today, the order books remain historical artifacts. Compared with this, both the riding breeches and the stag trophies succeed in drawing a line between historical heritage and today’s luxury business since the breeches are framed by new clothes, which are presented as being as sustainable as the historical trousers and the stag trophies also represent a symbol for the current customer service.

Limitations and implications for future research

Although the current study examined sign chains with reference to their consistence, this method cannot substitute qualitative or quantitative approaches where especially the consumer perception to semiotic references or the impact on brand identity can be measured.

Against this background, future research should also investigate which aspects of luxury brand identity are most important for customers. An additional semiotic analysis examining those artifacts representing a cohesive brand myth would be convenient. However, the construct of the brand myth as a different phenomenon should be measured by several semiotic approaches rather than the chosen one.

With reference to the lessons that were learned, the semiotic study should be translated into a management concept in which a step-by-step approach for the creation of notable brand heritage (and eventually myths) is offered. At last, it has to be noted that the study only analyzed some artifacts, but for a comprehensive analysis, several artifacts of different luxury shops should be included as well. As the focus of our study was on visual signs, semiotics are highly related to all dimensions of communication and therefore to a multisensual approach. Regarding future research, a composition of a qualitative and quantitative approach is thus needed.

Conclusion

Joseph Campbell, who argued from a literary and ethnological perspective, characterizes myths with reference to their ability to form the perception of our environment.

Destruction of the world that we have built and in which we live, and of ourselves within it; but then a wonderful reconstruction, of the bolder, cleaner, more spacious, and fully human life- that is the lure, the promise and terror, of these disturbing night visitants from the mythological realm that we carry within [49].

Mankind has been confronted with signs as long as it has existed. Signs offer opportunities to create identities containing traditionally established manners, attributes, and values. With reference to luxury marketing and management, signs can communicate a brand’s roots and heritage and anchor specific associations to it. Nonetheless, in order to authentically improve a brand’s identity, signified references have to be genuine and match the brand’s own history.

The particular benefit of our study lies in the presentation and qualitative application of semiotic elements to the analysis of a luxury brand’s heritage creation. Our results provide evidence that a textual corpus, e.g., a luxury shop design, reflects specific luxury values. Furthermore, complex structures of diverse signs and sign chains may create a unique brand heritage if the signified artifacts are in line with the brand’s history and reflect its current operative business. As a result, our findings offer some remarkable implications for luxury brand management, as well as future research in brand semiotics, luxury fashion, brand management, and consumer experience. Concerning brand management, the design of a shop should be composed of artifacts that provide a direct link between its traditional heritage and current corporate culture, such as customer relationship and craftsmanship. With regard to future research, more semiotic approaches combining brand heritage and myths should be examined. Furthermore, it is of special importance to discover the heritage myth communicated by signs and, thus, to determine specific successful designs in luxury brand marketing. From a quantitative point of view, our results can be assessed with reference to the customer experience or multisensory sign chains.

In the future, a luxury market may be expected to be even more competitive than today. Consequently, it will be even more essential to establish unique and authentic brands. Semiotic approaches may facilitate the communication of true values and thus establish living brand heritage myths. Therefore, we agree with the statement of T.S. Eliot regarding history and presence. If brands possess an extraordinary heritage, then they have to perpetuate it, day by day.

“The historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence.“ (T.S. Eliot, American- British Author).

In-Shop Expert Interview with Poppy Charles, Huntsman Director Press and Marketing, on March 10th 2015 (Summary)

1. In the shop, one may notice several patterns for sewing – on the ceiling, in frames, in the back of the shop.

The patterns that are used for decoration belonged to earlier customers. Some of the more prominent customer patterns, as those of Gregory Peck or Katherine Hepburn, are framed for a better conservation. Patterns such as these are still used today and kept in storage for new orders. Each new customer gets individual patterns.

2. In the shop, one may notice also several fabric samples – in books (old books, samples stapled by hand), in fabric sample catalogues, on rolls, and even already cut into pieces.

We store all fabric samples. By doing this, we are able to look for the same or equivalent fabric, even after decades for repairs or renewals. Some of the books placed in the shop present very old fabric samples. They are still used to look for rare old samples.

3. In the shop, one may also notice several order books from different decades and centuries.

Some of the order books are more than a century old. Each customer was captured in those books. This is also why our most prominent customers, such as earlier peerage and celebrities, can be found in those books. The books represent our long history of sophisticated customers. Today, we have replaced the order books with a computer system.

4. As a single artifact, one may notice some riding breeches in a glass box behind the pay desk.

The riding breeches belonged to the son of our founder’s descendant who moved to Africa. When his family moved back, they returned the trousers to our shop for archiving. Though they are more than hundred years old, they were used up to the 1990s.

5. As another single artifact, one may notice two mighty deer heads in the shop’s front.

In the early 20th century, a new customer came to London and visited Huntsman. He asked to leave his luggage in the shop since he wanted to have lunch before returning for measuring. Therefore, he left those two stag heads, but he never returned. His name was unknown, and so the stags have remained in our shop until today. While those stags may be prominent and appear typical for traditional English leisure and sometimes both wealthy and eccentric customers, many customers even today leave their belongings in our shop when they visit London.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Claire Shih WY. Agrafiotis K (2017) Competitiveness in a Slow Relational Production Network: The Case of London’s Savile Row Tailors. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 35(3): 143-155.

- König JCL, Wiedmann KP, Hennigs N, Haase J (2016) The Legends of Tomorrow: a Semiotic Approach Towards a Brand Myth of Luxury Heritage. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science 26(2): 198-215.

- König JCL, Haase J, Hennigs N, Wiedmann KP (2018) …and they lived luxury ever after: storytelling as a driver for luxury brand perception and consumer behavior. Luxury Research Journal 1 (4): 283-302.

- Urde M, Greyser SA, Balmer JMT (2007) Corporate Brands With A Heritage. Journal of Brand Management 15(1): 4-19.

- Aaker DA (1996) Building strong brands. Free Press, New York, USA.

- George M (2004) Heritage branding helps in global market. Marketing News 4(13).

- Aaker DA (2004) Leveraging the Corporate Brand. California Management Review 46 (3): 6-18.

- Kapferer JN, Bastien V (2009) The Luxury Strategy: Break the Rules of Marketing to Build Luxury Brands Kogan Page, London.

- Ligas C, Crepaldi F (2013) Semiomarketing and fashion semiology: The business language of fashion and luxury. International Journal of Marketing Semiotics 1: 132-139.

- Bargenda A (2014) The paradox of contemporary bank architecture: Building a new model of brand identity. International Journal of Marketing Semiotics 2: 6-22.

- Wiedmann KP, Hennigs N, Schmidt S, Wüstefeld T (2012) The Perceived Value of Brand Heritage and Brand Luxury. Managing the Effect on Brand Strength, Diamantopoulos A, et al. (edts): Quantitative Marketing and Marketing Management – Marketing Models and Methods in Theory and Practice. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden, pp. 563–583.

- Wuestefeld T, Hennigs N, Schmidt S, Wiedmann KP (2012) The impact of brand heritage on customer perceived value. der markt 51: 51-61.

- Oswald L (2012) Marketing Semiotics: Signs, Strategies, and Brand Value. Oxford University Press, Oxford, USA.

- Umiker-Sebeok J (edt) (1987) Marketing and Semiotics-New Directions in the Study of Signs for Sale, de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany, p.568.

- Hoshino K (1987) Semiotic Marketing and Product Conceptualisation. Umiker-Sebeok J (edt), Marketing and Semiotics- New Directions in the Study of Signs for Sale, de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany, pp. 41-55.

- Kawama T (1987) A Semiotic Approach to the Design Process. Umiker-Sebeok J (edt), Marketing and Semiotics- New Directions in the Study of Signs for Sale, de Gruyter, Berlin,Germany, pp. 57-70.

- Nöth W (1987) Advertising: The Frame Message. Umiker-Sebeok J (edt): Marketing and Semiotics- New Directions in the Study of Signs for Sale, de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany, pp. 279-294.

- Aaker DA, Keller KL (1990) Consumer Evaluations of Brand Extensions. Journal of Marketing 54(1): 27-41.

- Park CW, Milberg S, Lawson R (1991) Evaluation of brand extensions: the role of product feature similarity and brand concept consistency. Journal of Consumer Research 18(2): 185-193.

- Loken B, John DR (1993) Diluting Brand Beliefs: When do Brand Extensions have a Negative Impact? Journal of Marketing 57(3): 71-84.

- Martinez E, de Chernatony L (2004) The effect of brand extension strategies upon brand image. Journal of Consumer Marketing 21(1): 39-50.

- Buil I. et al. (2007) Brand extension effects on brand equity: a cross-national study. Thought Leaders International Conference on Brand Management, Birmingham, UK.

- Hagtvedt H, Patrick VM (2009) The broad embrace of luxury: Hedonic potential as a driver of brand extendibility. Journal of Consumer Psychology 19(4): 608-618.

- Jung K, Tey L (2010) Searching for boundary conditions for successful brand extensions. Journal of Product & Brand Management 19(4): 276-285.

- Manning P (2010) The Semiotics of Brand. Annual Review of Anthropology 39: 33-49.

- Roper S, Caruana R, Medway D, Murphy P (2013) Constructing luxury brands: exploring the role of consumer discourse. European Journal of Marketing 47(3/4): 375-400.

- Veg-Sala N, Roux E (2014) A semiotic analysis of the extendibility of luxury brands. Journal of Product & Brand Management 23(2): 103-113.

- Calvin C, Hobbes H (2003) An Introduction to Calvinball. Marketing and Sport 2(4): 597-580.

- Kessou A, Roux E (2008) A semiotic analysis of nostalgia as a connection to the past. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 11(2): 192-212.

- Burks AW (1949) Icon, Index, and Symbol. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 9(4): 673-689.

- Sonesson G (2013) The Natural History of Branching: Approaching to the Phenomenology of Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness. Signs and Society 1(2): 297-325.

- Mick DG (1986) Consumer research and semiotics: exploring the morphology of signs, symbols and significance. Journal of Consumer Research 13(2): 196-213.

- Eco U (1978) A Theory of Semiotics. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, USA.

- Hess-Lüttich EWB (1985) Social Interaction and Literary Dialogue II. Schmidt, Berlin, Germany.

- König JCL (2011) About the Power of Speech. V&R unipress, Göttingen, Germany.

- Rastier F (1995) Communication ou transmission? Césure 8: 151-195.

- Tresidder R (2010) Reading food marketing: the semiotics of Marks & Spencer!? International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 30 (9/10): 472-485.

- Nöth W (2000) Handbook of Semiotics. Metzler, Stuttgart, Germany.

- Rossolatos G (2012) A structuralist semiotic approach to the threat of aberrant decoding and positioning. Proceedings of the 11th international conference on research in advertising (ICORIA).

- Santos FP (2013) Brands as semiotic molecular entities. Social Semiotics: a Transdisciplinary. Journal in Functional Linguistics, Semiotics, and Critical Theory 23(4): 507-516.

- Poppy C (sa) Huntsman. Savile Row, London, Est. 1849. Show Media, London, UK.

- (2015) Huntsman established 1849.

- Anderson F (2015) Fashioning the gentleman: a study of Henry Poole and Co., Savile Row tailors 1861–1900. Fashion Theory 4(4): 405-426.

- Ross P (1996) Selling uniqueness. Manufacturing Engineer 75(6): 260-263.

- Breward C (2004) Fashioning London: Clothing and the Modern Metropolis. Berg, Oxford.

- Hüetlin T (2009) Old Money. Global Village: Why business expands at the most expensive haberdasher in crisis-ridden London. Der Spiegel, p. 118.

- Sykes P (2013) The man who dressed Bing Crosby, Gregory Peck, Laurence Olivier and Dirk Bogarde. How was it that Huntsman, the great English tailor, was adopted by crème de la crème of 1950s Hollywood? The Spectator.

- Krappmann L (2010) Structural Dimensions of Identity. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart, Germany.

- Campbell J (2004) The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA.

-

Jan CL König, Klaus-Peter Wiedmann, Janina Haase, Franziska Labenz, Nadine Hennigs. Becoming the King’s Men – the Semiotic Molecule of Luxury Brand Heritage. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech. 5(5): 2020. JTSFT.MS.ID.000624.

-

Brand Semiotics, Luxury brand management, Brand heritage, Brand identity, Luxury consumption, Myth, Framing

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.