Research Article

Research Article

An Evaluation of the Quality of Mens 100% Cotton Jersey Knit White T-Shirts

Jeanne Badgett, Department of Retailing and Tourism Management, Textile Testing Lab, University of Kentucky, USA.

Received Date: June 12, 2020; Published Date: June 22, 2020

Abstract

An evaluation of the quality of design, materials, construction, appearance, and performance of men’s 100% cotton jersey knit t-shirts from three retail categories: mass merchant (Brand MM), fast fashion (Brand FF), and better (Brand B) was performed. White t-shirts from each category were tested according to ASTM and AATCC standards and specifications [1]. Evaluations and measurements were conducted before washing, and after one, five, ten, and twenty laundry cycles. The t-shirts were evaluated for fabric weight, fabric count, color change, whiteness change, crocking, smoothness appearance, bursting strength, pilling, dimensional stability, and skewness. In appearance and performance testing, the ‘mass merchant’ t-shirts had the most results with ratings and measurements that would be considered the ‘best’ or more desirable. But from a statistical standpoint, none of the results for the ‘mass merchant’ retail category were significantly (p < 0.05) better than the ‘fast fashion’ or ‘better’ categories. In conclusion, the decision to purchase a t-shirt from these retail categories may depend on consumer expectations [2].

Keywords: Quality; T-shirt

Abbreviations: MM: the t-shirt brand purchased from a mass merchant retailer; FF: the t-shirt brand purchased from a fast fashion retailer; B: the t-shirt brand purchased from a retailer classified as ‘better’; ASTM: Society for Testing and Materials; AATCC: American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists

Introduction

Is there really a difference between a $5 white t-shirt and a $125 white t-shirt? Lifestyle reporter, Julia Brucculieri J [3], posed this question to textile experts and learned that, although there are several factors that determine the price of a white t-shirt, quality is not directly linked price, and the value assessment is up to the consumer [3].

Apparel price is inherently defined by how a brand needs to position its product relative to where the competition is, but pricing is also heavily dependent on consumer expectations [4,5]. Consumers are value driven and expect more for what they are prepared to pay [6]. Because the relationship between product pricing, positioning, branding, and perceived quality is complex, it is crucial that an ap parel retailer finds the right balance between these criteria in order to remain profitable and satisfy the consumers’ desire for value [7].

Consumers benefit by understanding the different features in products because they are bombarded with a plethora of brands of the same merchandise in varying degrees of quality [8]. Under the vast umbrella of fast fashion retailers and traditional retailers, apparel quality and pricing can be so indiscriminate in nature; it is difficult for consumers to distinguish differences in order to ascertain its value [9,10]. Therefore, manufacturers, brands, and marketers use quality as a concept to differentiate their product from their competitors [11]. Chowdhary U [8]states, “Quality products tend to meet or exceed the consumer expectation”. Consumers want price tags that are commensurate with the quality, yet apparel retailers are not consistently delivering on that desire because product pricing and positioning is not a reliable indicator of quality [12,13]. Some apparel companies have resorted to altering production methods to remain profitable [14]. And as a result of rapidly changing productions methods and quality being in the eye of the beholder, gone are the days when the retailer and cost of apparel indicate quality [15,16].

Purpose

The purpose of this research was to evaluate the quality of design, materials, construction, appearance, and performance of Mens 100% cotton jersey knit white t-shirts from three retail categories: mass merchant, fast fashion, and better.

Research objectives of this study were to:

1. Identify and compare the product specifications of men’s 100% cotton jersey knit white t-shirts at three retail categories.

2. Measure and compare the appearance and performance characteristics of men’s 100% cotton jersey knit white t-shirts at three retail categories before and after home laundering.

3. Compare the appearance and performance characteristics of men’s 100% cotton jersey knit white t-shirts at three retail categories to the ASTM D4154 Standard Specification requirements[ 17].

Review of Literature

Introduction

T-shirts are “mundane, quite unobtrusive…and amongst the commonest of mass-produced garments” [18]. Worn day or night, in both leisure and luxury contexts, t-shirts are considered “a basic, all purpose form of clothing which is universal in application” [18]. And their omnipresent nature has enabled these garments to become a global phenomenon. Some t-shirts have unisex sizing while others can reflect fashion trends through oversized or fitted styling, deep armholes, and varied lengths [19]. The year round, season less appeal of t-shirts is achieved with simple changes in the color, fabric weight, or sleeve length [20].

At the turn of the twentieth century, the US Navy began to issue undershirts to be worn under service Mens’ uniforms, leading to the crew wearing just the undershirt to avoid soiling their uniforms while performing chores and dirty jobs. Undershirts soon became available to the public and were quickly adopted by farmers and more laborers as the garments were inexpensive and easy to maintain. The undershirt as outerwear was further popularized in the 1950s when worn on-screen by the virile actors Marlon Brando and James Dean as they portrayed characters with defiant spirits in the movies A Streetcar Named Desire and Rebel without a Cause. It has since materialized as a multifunctional garment that can be easily worn by anyone regardless of gender, age, race, fashion taste, social status, income, profession [18,20].

Comfortable, durable, and versatile, t-shirts have mass appeal because they may be worn as outerwear or underwear [21]. T-shirts are the most purchased Men’s clothing item[22]. Worldwide approximately 3,800 t-shirts are sold every minute, creating a market worth over three billion dollars. Because a t-shirt can cost so little, it is a clothing option for consumer’s at all social and economic levels. The adaptability of the t-shirt has made it the “everyday garment for so called under classes, but in other social contexts it can be a high fashion product with a chic designer logo for which an affluent consumer will pay an exorbitant price” [18]. But even though “there are many different classes of t-shirts, but they can themselves be without absolute links to class”[18].

Over the years, Mens undershirts have functioned as t-shirts, especially the classic white crew neck t-shirt. But as the technical definitions of a t-shirt and undershirt are not the same, some manufacturers have confused things further by interchanging the terms t-shirt and undershirt in their promotion and packaging. They are both marketed and consumed to be worn alone or under another shirt. Some purists would argue that an undershirt is not a t-shirt because they believe undershirts are meant to be worn solely as undergarments. Undershirts tend to be made of thinner fabrics, and sometimes feature moisture wicking properties (“Why You Should Care about what’s Under There,” n.d.). The purpose of an undershirt is to absorb sweat and to provide a defensive layer between the wearer and his more expensive clothing. An undershirt can also provide insulation when needed, and some styles offer compression to the torso area to provide a slimmer appearance [23]. In these instances, the undershirt may be designed around function instead of form (“Why You Should Care about what’s Under There,” n.d.). Ingham’s viewpoint that “t-shirts are thicker than undershirts because they are designed to be worn on their own and not necessarily as a layer under something else” is limited because “textile technology has developed fabrics that look heavy without the weight” [24].

T-shirts can be manufactured with varying degrees of quality and construction methods. And, the wide range of prices at which they are sold may not always be consistent with the quality level [20,22,23]. Glock RE, et al. [20] state that “undershirts have more consistency between price and quality; whereas outerwear t-shirts vary widely in quality in price and sometimes rely more on emotional appeal than intrinsic quality”. But through this wide variety of t-shirts, the needs and expectations of consumers can be met [25].

T-shirt manufacturing is typically dominated by large companies that produce high volumes. Because the t-shirt is a basic apparel item [26], it can be continuously manufactured and remain relatively unchanged over multiple fashion cycles. This allows for high levels of automation and specialized equipment [27]. T-shirt fabrics are primarily 100% cotton or cotton and polyester blends; all cotton is generally used in making better quality t-shirts, but other factors such as yarn type, fabrication, design treatments, and fabric finishes can also affect quality. Styling variations that impact quality may be seen in the neckline, trims, the inclusion of pockets, or applied design.

The quality properties of cotton fibers and fabrics make 100% cotton t-shirts more desirable for daily wear. A 2015 Cotton Incorporated survey of 500 consumers indicated that 79% agree that cotton fibers make better quality clothing [28]. However, the influence of sportswear on everyday fashion has resulted in more t-shirts with blends of man-made fibers that provide performance features (“A comparison of men’s t-shirts”). It is also because of escalating cotton prices that some brands and retailers began incorporating more man-made fibers into clothing. “Cotton dominant clothes (containing 51% cotton or greater) declined 11.8 percent in 2011 compared to 2010, while imports of predominantly manmade apparel increased 8.3 percent” [28]. Rising cotton prices have put pressure on manufacturers to raise t-shirt prices, use lower quality cotton, or incorporate a cotton blend (Smith, 2014). But ultimately, fabric quality is impacted by the combination and interaction of properties and characteristics of each component used to produce and finish the fabric [29].

Fabric weight is a factor that determines cost and quality, as well as its suitability for the intended use and comfort of the wearer [30]. However, “there isn’t necessarily a correlation between the thickness of a t-shirt’s fabric and its quality” [35]. Mens fashion blogger, Jamie Rice [27] relates higher fabric weight to “cheap undershirts [made with] thicker cotton that has bulkier neck and arm seams” [27]. And although thicker, heavier weight t-shirts may not move as freely, they may be more durable, which is perceived as a quality attribute [27]. Conversely, lightweight t-shirts may be luxuriously thin, produced with fine yarns using costly methods to attain a delicate fabric weight. But smaller, finer yarns tend to be weaker, and lightweight t-shirts may drape too limply over the body. Although fabric weight is measureable way to compare t-shirts and “fabric itself provides a foundation for quality, a high-quality fabric does not guarantee and high quality garment”.

The characteristics for a perfect t-shirt depend on the desires of the consumer. Quality perceptions and preferences “guide the choices for t-shirts that are fitted or relaxed, thick or thin, long or short, and crisp or worn”. The pursuit of manufacturers to provide a perfect t-shirt has led to higher prices for some shirts. And according to Jeffrey Silberman, professor and chair of the Fashion Institute of Technology’s Textile and Development Marketing program, “you’re not going to get [high quality] properties with a shirt that sells for $5.99”. Yet cost does not always reflect aesthetic or durability benefits [30] and quality is a multidimensional construct that cannot measured by a single attribute.

Methodology

The purpose of this research was to evaluate the quality of design, materials, construction, appearance, and performance of men’s 100% cotton jersey knit t-shirts from three retail categories: mass merchant, fast fashion, and better. Retail categories were represented by brand “MM”, brand “FF”, and brand “B” respectively. The ‘mass merchant’ brand (MM) is made by an American company and is sold at a variety of national big-box retailers as well as department stores. The ‘fast fashion’ brand (FF) is made by a publically traded international company with stores in over 60 countries. The ‘better’ brand (B) is a privately-owned company established over 200 years ago with stores in over 70 countries.

A quantitative, quasi-experimental design was utilized to evaluate the t-shirts according to industry standards and procedures. The t-shirt sample set was chosen based on the assumption of a positive relationship between price and quality and the extended connection between price and retail category [31,32]. Although one impetus for this research is derived from the view that the retail category is no longer indicative of quality, Fasanella [17] states that [based on retail category], “quality levels typically increase or decrease accordingly”.

All of the t-shirts were 100% cotton jersey knit with short sleeves and a crewneck style without pockets or other adornments. White t-shirts and navy t-shirts from each retail category were selected to provide diversified data. The white t-shirts were sold in a pack of multiples, while the navy t-shirts of each brand were sold individually. The t-shirts were marketed to be worn alone or as an under layer. In all, there were 78 t-shirts: 13 white MM, 13 navy MM, 13 white FF, 13 navy FF, 13 white B, and 13 navy B. The 13 t-shirts within each grouping were identical. This quantity provided enough fabric and enabled observations and measurements to be collected from the t-shirts before laundering, and after the t-shirts were washed and dried one, five, ten, and twenty times. However, due to the large amount of data collected, only the data and results from the navy t-shirts are presented here.

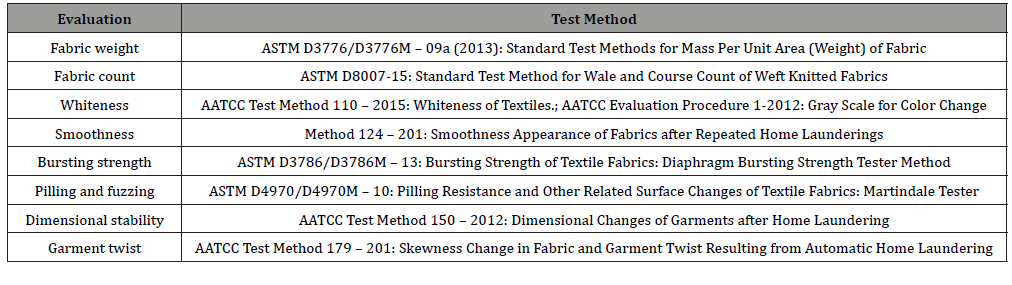

Table 1:Test methods.

Key variables of the experimental segment included the recommended test methods designated in the ASTM D6321/D6321M-14: Standard Practice for the Evaluation of Machine Washable T-Shirts. Test methods are listed in Table 1 and a detailed experimental design is included in the original thesis. Instruments used for direct testing of the apparel were the specified textile testing equipment located in the University of Kentucky Textile Testing Laboratory. When required, samples and specimens were conditioned for a minimum of four hours in an atmospheric chamber, registering 70° ± 2° Fahrenheit and with a relative humidity of 65% ± 5%, prior to testing and evaluation, as set forth by the ASTM D1776 Standard Practice for Conditioning and Testing Textiles [17].

The t-shirt care labels were reviewed to establish washer and dryer cycles that would closely mimic a consumer’s laundry habits. T-shirts were laundered, face-side out, in residential washers and dryers for 20 cycles, with testing before the first cycle, and after the first, fifth, tenth, and twentieth cycles. Two identical top-load, center- agitator washers, and two identical electric tumble dryers were used. The white t-shirts were laundered separately from the navy t-shirts. Both loads were washed in ‘large level ’of‘ warm water (40 °C / 104 °F), on a 35-minute ‘Colors/Regular’ cycle, using 40 grams of a national brand of liquid detergent. The t-shirts were dried on a medium, ‘timed dry’ cycle for 60 minutes.

The t-shirt design specifications were evaluated by comparing the sizing and fit of the new t-shirts to the technical measurement specifications and tolerances for men’s size large t-shirts, sourced from The Apparel Design and Production Hand Book [33]. Materials were evaluated through fabric weight at all five testing intervals and fabric count was collected initially and after the final laundering cycle. The construction specifications were evaluated on the t-shirts before laundering. Differences in stitch types, seam and hem types, and the order of garment assembly were compared.

Changes in appearance were evaluated instrumentally and subjectively. The whiteness index was measured with a spectrophotometer. Ratings for subjective change in whiteness and smoothness retention were assigned by the researcher, according to the AATCC reference standards. A visual inspection of all stitches, seams, hems, and necklines was conducted initially, and after laundry cycles one, five, ten, and twenty, to assess each shirt’s ability to maintain its original appearance. Durability and performance were assessed by measuring bursting strength, pilling propensity, dimensional stability, and skewness.

Data analysis

Numerical data was entered into Excel software to calculate descriptive statistics. For data analysis, Excel data was imported to Minitab statistical software to complete a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A 95% confidence interval with a significance level (α) of 0.05 was used to determine the statistical significance. To interpret results, data were grouped by testing interval and retail category. The data was statistically analyzed after washes FIVE and TWENTY to ascertain differences and similarities and to provide rankings according to the garment specifications. Results from select tests were compared to the ASTM D4154–14: Standard Performance Specification for Men’s and Boy’s Knitted and Woven Beachwear and Sports Shirt Fabrics to determine if the t-shirts met voluntary minimum ratings. Numerical data and statistical significance are presented in Tables 2-5.

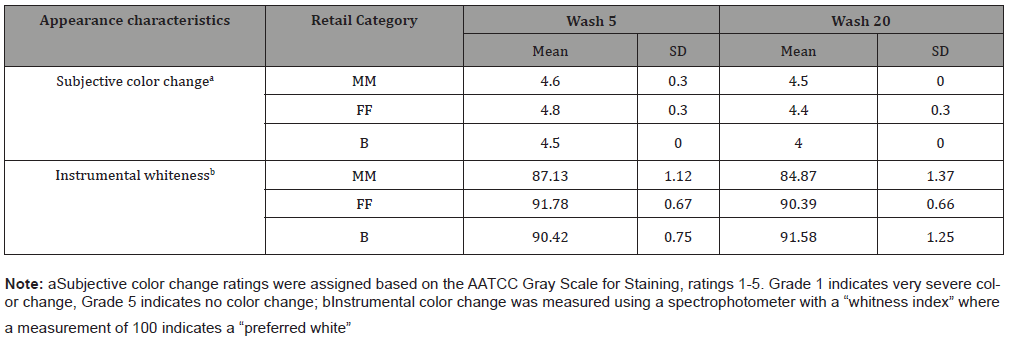

Table 2:Descriptive data for appearance characteristics, White T-Shirts.

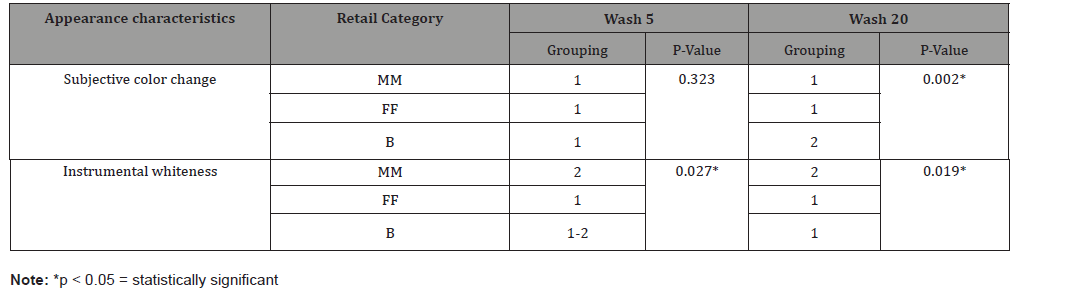

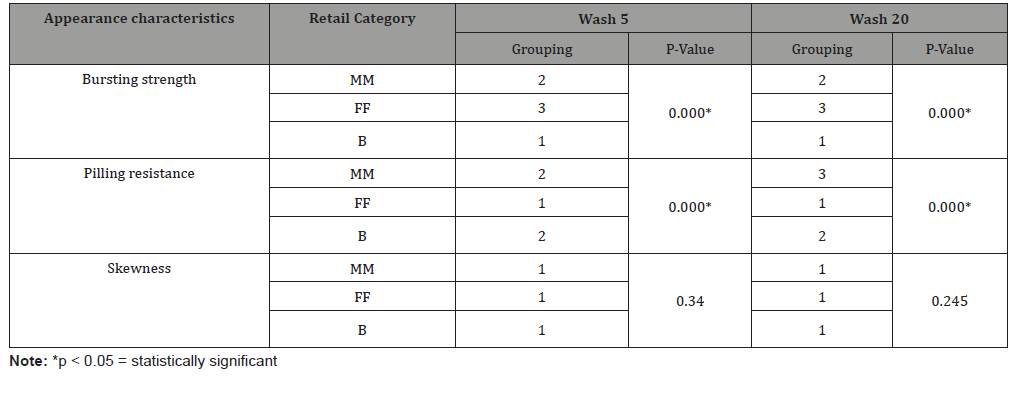

Table 3:Statistical significance of appearance characteristics data, White T-Shirts.

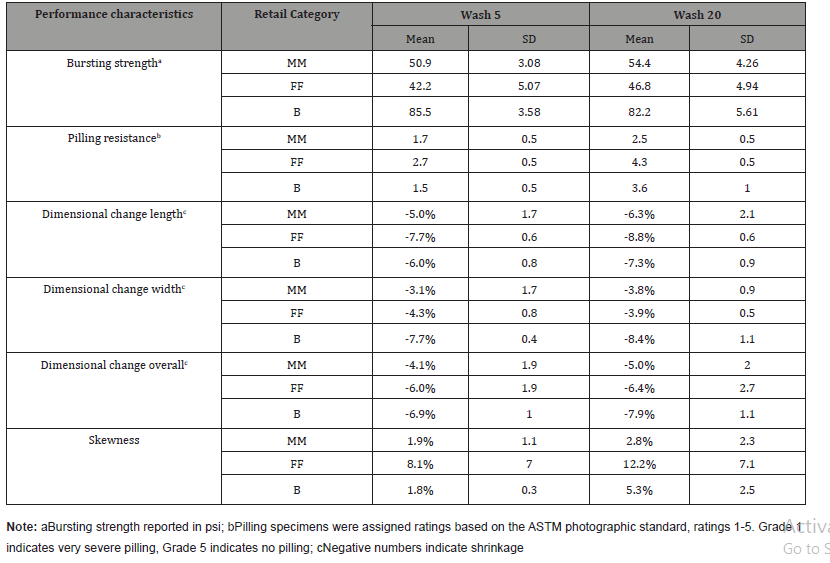

Table 4:Descriptive data for performance characteristics, White T-Shirts.

Table 5:Statistical significance of performance characteristics data, White T-Shirts.

Results and Discussion

The purpose of this research was to evaluate the quality of design, materials, construction, appearance, and performance of Mens 100% cotton jersey knit t-shirts from three retail categories: mass merchant, fast fashion, and better[34]. Observations and measurements were collected from new t-shirts, and after the t-shirts were washed and dried one, five, ten, and twenty times. The t-shirts evaluated in this study were easily differentiated by brand and price; but as a result of this research, the t-shirts were also differentiated by design, materials, construction, appearance, and performance.

Due to the large sample size and data set, the focus of this discussion and statistical analysis is the data collected from the white t-shirts after washes five and twenty. Data for the navy t-shirts are presented in a previous Journal of Textile Science & Fashion Technology article published on July 09, 2019 http://dx.doi.org/10.33552/ JTSFT.2019.03.000557. A product tested after five washes should reflect how it will function after residual and/or temporary finishes are removed. Results after twenty washes are an indication of the expected serviceability of a garment throughout its wear. Tables in Appendix B of the full thesis present the detailed data for both white and navy t-shirts collected at all five testing intervals. When applicable, results are discussed in comparison to the ASTM D4154–14: Standard Performance Specification for Men’s and Boy’s Knitted and Woven Beachwear and Sports Shirt Fabrics.

Design and materials specifications

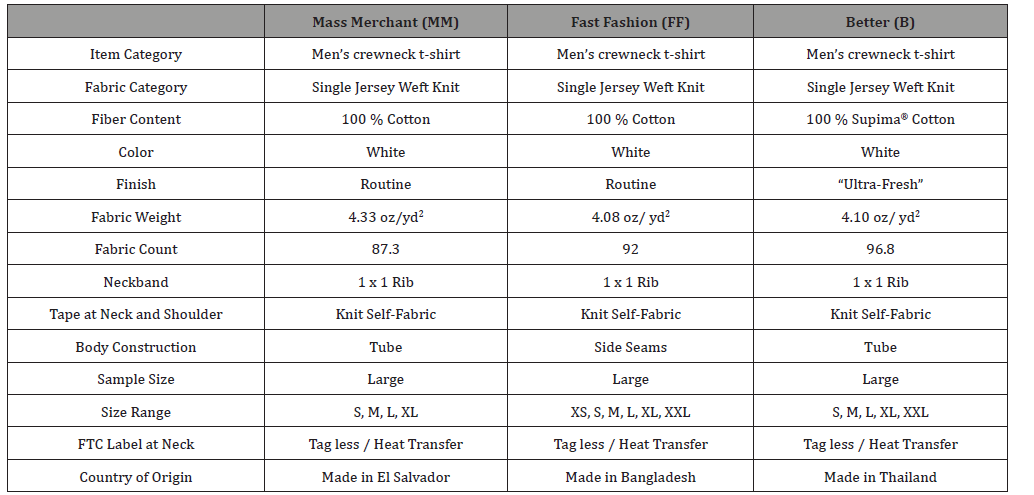

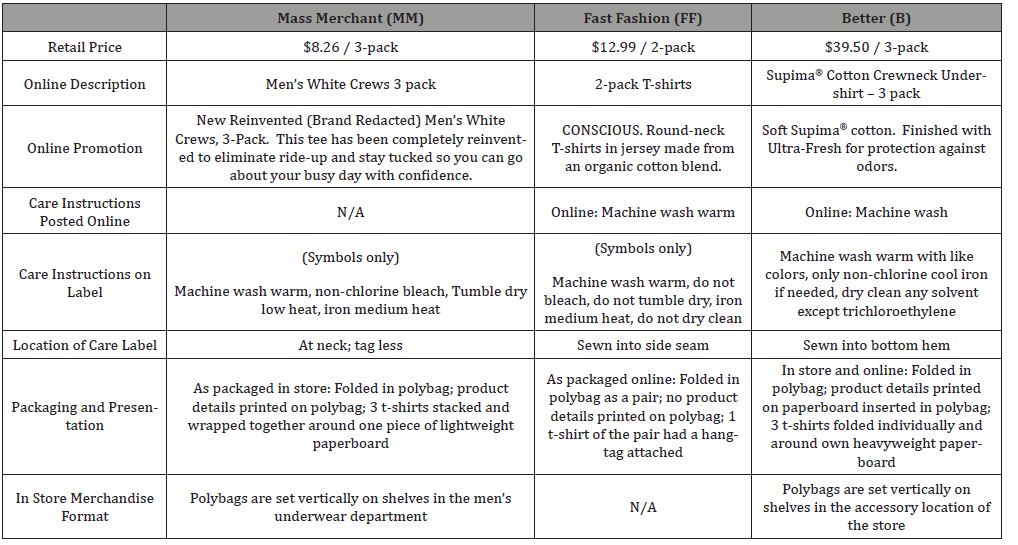

A summary of style and materials, as well as price and promotion details, are outlined in Tables 6 &7.

Table 6:Style and materials summary, white T-Shirts.

Table 7:Price, Promotion, and Packaging Details, White T-Shirts.

Size and fit: All t-shirts exhibited a wide range of size and fit measurements, with many of them outside the tolerances specified in The Apparel Design and Production Handbook: A Technical Reference, pp. 4•127, 7•10 [35]. Three essential measurements that impact fit are body length, chest width, and neckline circumference. For a men’s size large t-shirt, the technical specification of the body length is 30” with a tolerance of ± 3/4”. All three t-shirt retail categories were within that tolerance. The technical specification of the chest width is 48” with a tolerance of ± 1/2”. All three categories of t-shirts had chest widths smaller than 48 ±1/2” tolerance. The technical specification of neckline circumference is 20 1/2” with a tolerance of ± 3/8”. The B t-shirts were within the tolerance range. The MM and FF t-shirts were greater than the 20 1/2 ± 3/8” tolerance. The B t-shirts were smaller than 20 1/2 ± 3/8”.

Fiber content and finish: All of the t-shirts were labeled as having“100% cotton” fiber content. This was verified with a chemical fiber analysis. However, the B t-shirts identified the variety of cotton used as Supima®, which is considered to be higher quality because its long, staple fibers produce softer, smoother, and stronger fabrics. The B t-shirts were also described as being finished with “’Ultra-Fresh’ for protection against odors.”

Fabric weight: Fabric weight is a factor that determines cost and quality, as well as its suitability for the intended use and comfort of the wearer. However, “there isn’t necessarily a correlation between the thickness of a t-shirt’s fabric and its quality”. All of the fabric weight specimens were within a typical “light top weight t-shirt” range of 4 to 6 oz/yd² [4]. The t-shirts with the lightest fabric weight after five and twenty washes were the FF at 4.43 oz/yd² and 4.27 oz/yd² respectively. The t-shirts with the heaviest fabric weight after five and twenty washes were the B at 4.83 oz/yd² and 4.78 oz/yd² respectively. The final fabric weights of all t-shirts increased after washing and drying as a result of shrinkage.

Fabric count: For all t-shirts, the initial fabric counts ranged from 87.3 to 96.8. After twenty washes, the fabric counts ranged from 93.5 to 107.0. Similar to fabric weight, the increase in fabric count was due to shrinkage. MM t-shirts had the lowest fabric counts and B t-shirts had the highest fabric counts.

Construction specifications

Stitch types: A garment constructed of a jersey knit fabric, such as that used in the sample, would typically have a stitch length of 10 to 12 SPI [36]. The MM t-shirts included stitching that ranged from 9 to 13 SPI, the FF t-shirts included stitching that ranged from 10 to 12 SPI and the SPI of the B t-shirts ranged from 13 to 15.

There were four classifications of stitches used in the construction of the t-shirts: 101 (chain stitch), 406 (cover stitch), 504 (3 thread over edge), and 514 (4 thread over edge). Seams with different classifications are noted here. The MM and B t-shirts used a class 504 stitch to close the underarm seam, while the FF t-shirts used a more-costly class 514 stitch for this operation. The MM t-shirts used a class 504 stitch in the armscye seem and the FF and B t-shirts used a class 514 stitch. The neckband topstitching, which was used only on the MM t-shirts, was a class 406 stitch. The body of the MM and B t-shirts were a tube construction, therefore only the FF t-shirts had side seams, and they were constructed with a class 514 stitch.

Seam and hem types: All three retail categories featured the same seam classifications. The FF and B t-shirts (constructed with side seams) utilized a superimposed seam for the closure. The placket creating the side vent on the B t-shirts included an edge finish and a lapped seam. All t-shirts were constructed with the same edge finish on the sleeve and bottom hems, however, the width of the hems varied between 11/16” (MM category) to 1” (B category). In general, wider hems tend to hang more smoothly and are less prone to roll when the fabric is stretched. Therefore, higher quality garments tend to have wider hems than those on lower quality garments. Because wider hems require more fabric, they can cost more (Keiser & Garner, 2012).

Assembly: There was a difference in the order in which the underarm seams and sleeve hems were constructed. The sleeve hem of the MM t-shirts was constructed first, followed by the closure of the underarm seam. This can result in a visible underarm seam that extends to the edge of the sleeve, possibly causing discomfort to the wearer. Contrarily, the t-shirts from FF and B closed the underarm seam first, and then finished the sleeve hem. This is a desirable, yet more expensive, process to construct a sleeve hem [36]. Finally, because the body of the FF t-shirts was constructed with side seams, the sleeves inserted first, followed by the closure of the side seam [37].

Appearance specifications

Subjective whiteness change: After five washes, there was no statistically significant difference (p=0.323) between the whiteness change ratings of all retail categories (MM 4.6, FF 4.8, B 4.5). After twenty washes, the B t-shirts were perceived to have the most change in whiteness (4.0) and this was significantly different (p=0.002) than the whiteness change for the MM t-shirts (4.5) and the FF t-shirts (4.4).

Instrumental whiteness change: After five washes, the whiteness index of the MM t-shirts (87.13) was significantly lower (p=0.027) than the whiteness index of the FF t-shirts (91.78). There was no significant difference between the whiteness index of the B t-shirts (90.42) and the MM and FF t-shirts. After wash twenty, the whiteness index of the MM t-shirts (84.87) continued to be the lowest, but after this interval, it was significantly lower (p=0.019) than both the FF (90.39) and B (91.58) t-shirts. There was no significant difference in whiteness between the FF and B t-shirts.

Appearance of stitches/seams/hems/neckline after laundering: After washing, there was puckering and roping in the armscye seams on all of the t-shirts. The narrow hem depths on the MM t-shirts contributed to hem rolling after laundering, detracting from the appearance.

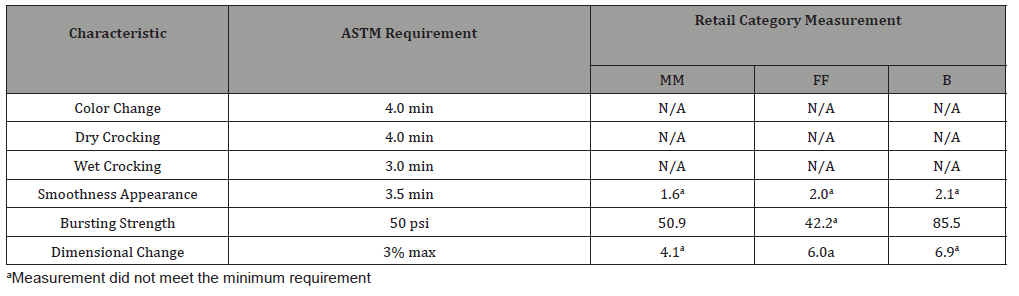

Smoothness appearance: After five washes, the MM t-shirts had the lowest rating (1.6) and the B t-shirts had the highest rating (2.1). After twenty washes, the MM t-shirts continued to have the lowest rating (2.6) and the FF and B t-shirts had the same, higher rating (3.0). Smoothness appearance improved for all t-shirts and this can be attributed to the relaxation of the fabric yarns and the removal of any sizing finishes during laundering. A minimum smoothness rating of 3.5 is specified by the ASTM D4154 standard. None of the white t-shirts in these retail categories met this minimum. Data for smoothness appearance was not statistically analyzed because of the low number of replications (Table 8).

Table 8:ASTM D4154 Specification Requirements Compared to T-Shirt Data, After 5 Washes, White T-Shirts.

Performance specifications

Fabric bursting strength: The initial bursting strengths for the t-shirts, from lowest psi to highest psi, were as follows: FF 46.8, MM 50.9, and B 82.5. After five washes, the differences in bursting strength were statistically significant (p=0.000) for all three t-shirts; lowest psi to highest psi was: FF 42.2, MM 50.9, and B 85.5. After twenty washes, the differences in bursting strength were statistically significant (p=0.000) for all three t-shirts; lowest psi to highest psi was: FF 46.8, MM 54.4, and B 82.2. Only the MM and B t-shirts met the ASTM D4154 minimum bursting strength of 50 psi at all intervals.

Pilling and fuzzing: After five washes, the difference in the pilling rating of the FF t-shirts (2.7) was statistically significant (p=0.000) compared to the MM (1.7) and B t-shirts (1.5). And after wash twenty, the ratings for the t-shirts improved due to the removal of short fiber ends on the fabric surface, resulting in a statistically significant difference (p=0.000) between all t-shirts. The FF had the least degree of pilling (4.3) and the MM had the worst degree of pilling (2.5), while the B t-shirts were rated in between (3.6). Although the ASTM D4154 standard does not specify a minimum pilling rating, guidelines published in 2010 set forth by Brand FF Quality Standards & Requirements for knit tops require minimum pilling ratings of 3.0 after five washes. None of the retail categories met that minimum requirement at washes five [38].

Dimensional stability: After five and twenty washes, the FF t-shirts exhibited the highest change (shrinkage) in length (7.7% and 8.8%), while the MM shirts exhibited the least percent shrinkage (5.0% and 6.3%). Decrease in t-shirt width was the highest for the B t-shirts after five and twenty washes (7.7% and 8.4%), while the MM shirts exhibited the least percent change in width (3.1% and 3.8%). The results for overall dimensional change, show that, after five and twenty washes, the B t-shirts exhibited the highest overall shrinkage (6.9% and 7.9%), while the MM shirts exhibited the least percent overall shrinkage (4.1% and 5.0%).

A 3% change in either shrinkage or growth is the ASTM D4154 maximum for dimensional change. None of the white t-shirt retail categories met this requirement.

Garment twist: After five washes, there was no statistically significant difference (p=0.340) in the skewness change between the MM (1.9%), FF (8.1% [SD 7.0]), and B t-shirts (1.8%). And after twenty washes, there was no statistically significant difference (p=0.245) in the skewness change between the MM (2.8%), FF (12.2% [SD 7.1]), and B t-shirts (5.3%). Maximum skewness change is not specified by the ASTM D4154 standard; however, guidelines published by Brand FF recommend skewness to be less than 5%. Using these suggestions as a guide, the white FF t-shirts exceeded the maximum rating after washes five and twenty (8.1% and 12.2%), and the B t-shirts exceeded this after wash twenty (5.3%).

Conclusion

The purpose of this research was to evaluate the quality of design, materials, construction, appearance, and performance of Mens 100% cotton jersey knit t-shirts from three retail categories: mass merchant (brand MM), fast fashion (brand FF), and better (brand B), in the colors of white and navy. Due to the large data set, remarks for only the white t-shirts are concluded below (the complete narrative for both colors of t-shirts is in the original thesis).

Research objectives of this study were to:

Identify and compare the product specifications of men’s 100% cotton jersey knit t-shirts at three retail categories

All of the t-shirts featured the same basic T design. The bodies of the MM and B t-shirts were a tube construction. The body of the FF t-shirts was assembled with side seams. All of the t-shirts were 100% cotton. However, the B t-shirts were advertised as made with Supima® variety cotton and treated with an “ultra fresh” to yield an odor resistant fabric. With the differences in cotton variety and fabric finishes, the B fabric could be perceived by the consumer to be of higher quality. There was no difference in the fabric weights of the t-shirts and they all increased from the initial weight, over the course of washing and drying, and measured heavier after wash twenty.

The ‘fast fashion’ category t-shirt (brand FF) was constructed with the same, more durable, types of stitches as the ‘better’ t-shirt category (brand B)[39]. However, the stitches per inch (SPI) were the highest in the ‘better’ t-shirt (brand B). Stitch length directly relates to the amount of labor required to sew a garment. Garments with a lower SPI can be sewn in a shorter period of time, impacting the cost of manufacturing. A higher SPI is associated with higher quality apparel. Topstitching was only used on the MM t-shirt. This is also an indicator of better-quality garments. The t-shirt order of assembly varied among the retail categories of white t-shirts. The ‘mass merchant’ t-shirt sleeve hem was constructed first, followed by the closure of the underarm seam. By finishing the hem before closing the underarm seam, a lower cost production method was used for the ‘mass merchant’ t-shirt [36]. Contrarily, the ‘fast fashion’ and ‘better’ underarm seams were closed first, followed by the finish of the sleeve hem. Second, the ‘fast fashion’t-shirt’s sleeves were inserted first, followed by the closure of the side seam.

Measure and compare the appearance and performance characteristics of Mens 100% cotton jersey knit t-shirts at three retail categories before and after home laundering

Before laundering, the appearance of the three categories of t-shirts was similar. The whiteness of the t-shirts was perceived to be similar according to AATCC Gray Scale for Staining. Instrumental whiteness data showed the MM t-shirts were the least white according to the whiteness index. With regard to performance, a consumer is unlikely to perceive much difference if the t-shirts were worn before laundering. This research tested bursting strength on the t-shirts initially, and the FF retail category had abursting strength psi measurements (46.8 psi) that was below the ASTM D4154 minimum requirement of 50 psi. Pilling would be least noticeable on the FF t-shirt if worn before laundering.

After washing, there was puckering and roping of the armscye seams on all of the t-shirts. The neckband width of the white FF t-shirts was narrow and lacked topstitching, which caused it to roll. Also, the narrow hem depths on the MM and B t-shirts contributed to hem rolling after laundering, detracting from the appearance.

As a group of white t-shirts, the subjective change in the whiteness after laundering was not apparent. Instrumental values reported that, after twenty washes, the B t-shirts were the ‘whitest’ (91.58), however, a difference in whiteness was perceived only when the white t-shirts from each brand were placed next to each other. If a consumer were to compare the appearance of pilling on the surface of the t-shirts after laundering, they would probably be most satisfied with the t-shirts in ‘fast fashion’ t-shirts.

Bursting Strength after laundering changed less than 1% for the FF and B t-shirts. The MM bursting strength increased by 6.9%. Only the MM and B retail categories met the minimum requirements for bursting strength. And although the B t-shirts had the highest bursting strength, it was not significantly better than the MM category. A consumer is unlikely to be disappointed with the bursting strength of any of the t-shirts [41].

The dimensional change in length was the highest in the FF t-shirts, and the highest change in width was in the B t-shirts. The percent decrease in length and width would impact the size or fit of the t-shirt. The least percent change in the overall size was exhibited in the MM t-shirts. The MM t-shirts also exhibited the least percent skewness, followed by the B t-shirts. This is unusual because the MM and B t-shirts were constructed with a tubular knit fabric. The circular knitting process used to achieve the tubular construction of the MM and B fabric has a propensity to experience distortion.

Compare the appearance and performance characteristics of Mens 100% cotton jersey knit t-shirts at three retail categories to the ASTM D4154 Standard Specification requirements

The ASTM D4154 standard specifications applicable for white t-shirts are smoothness appearance, bursting strength and dimensional change. Only the minimum bursting strength psi of 50 was met after five washes by the MM t-shirts (50.9) and the B t-shirts (85.5).

Implications

This assessment of Mens 100% cotton jersey knit t-shirts in three retail categories provided an objective comparison of similar merchandise. The selection of a homogenous sample of a basic apparel item, that was not as dependent on fashions and trends [27], supports this objectivity. Furthermore, the sample set was not limited by end use; a “dilapidated t-shirt can be as much a leisure choice for the wealthy, as a necessity for the poor” [18].

In appearance and performance testing, the ‘mass merchant’ t-shirts had the most results with ratings and measurements that would be considered the ‘best’ or more desirable. But from a statistical standpoint, none of the results for the ‘mass merchant’ retail category were significantly (p < 0.05) better than the ‘fast fashion’ or ‘better’ categories. In conclusion, the decision to purchase a particular t-shirt from these three retail categories depends on consumer expectations and their perception of quality and value.

Limitations and Recommendations

This research was restricted due to a non-randomized, convenience sample, without control over the manufacturers’ lots from which the materials originated. Additionally, the evaluations and data provide a comparison among only t-shirts in three retail categories, as opposed to other styles of garments or other retail categories. To simplify the experimental design and to replicate the laundry habits of a typical consumer, all the t-shirts were laundered using the same wash and dry parameters. A 40 °C, “warm water” wash was used, followed by a drying cycle on medium heat. However, the care label of the MM and B t-shirts recommended a drying cycle on low heat and the FF t-shirts recommended avoiding the dryer. Had the t-shirts been laundered according to the specified care instructions, results may have differed. And although the suitability of the t-shirts’ designs, materials, construction, appearance, and performance was evaluated before and after laundering, the t-shirts were never worn. Speculation about consumer satisfaction was inferred based on results collected in a laboratory setting. The t-shirts may perform differently if exposed to other environmental stressors, including wearer usage, soiling, and individual home laundering methods. In the realm of apparel testing [41], it is not always known how a textile fabric will be used by consumers, and because of the variability of consumer behavior [42], even when the end use is known, the actual performance expectations may not be well understood [43].

Recommendations for future research are to include a wear study to supplement data acquired through test methods that are limited by a laboratory setting. Also, because exposure to body oils and environmental soils during wear may impact the appearance of the t-shirt fabrics, the addition of soil ballast to the wash cycle would help simulate this. The ability to obtain samples from different production lots would aid in the randomization of the experimental design. And the degree of accuracy could be improved if more samples were included at each testing interval. Other recommendations are to introduce variables in the laundering conditions. Finally, with the increasing popularity of the slow fashion movement, which focuses on quality-based instead of time-based fashions [44-46]? A study comparing t-shirts from this quality-based production method to the MM, FF, and B sample would be informative.

Acknowledgement

Thank you to Dr. Elizabeth Easter and the university of Kentucky textile testing lab for supporting this research.

Conflict of Interest

There are no known conflicts of interest in this research.

References

- AATCC (2016) AATCC technical manual. Research Triangle Park, NC: American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists: 91.

- (2016) Impact of fast fashion on the retail industry.

- Brucculieri J (2018) The difference between a $5 white tee and a $125 white tee.

- Bubonia J (2014) Apparel quality: A guide to evaluating sewn products. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Inc, USA.

- Carroll M (2012) How fashion brands set prices.

- De Klerk HM, Lubbe S (2008) Female consumers’ evaluation of apparel quality: Exploring the importance of aesthetics. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 12(1): 36-50.

- D’Arienzo B (2016) Reshoring success stories: What’s branding got to do with it?

- Chowdhary U (2002) Does price reflect emotional, structural or performance quality? International Journal of Consumer Sciences 26(2): 128-133.

- Kim H, Choo HJ, Yoon N (2013) The motivational drivers of fast fashion avoidance. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 17(2): 243-260.

- Romeo L (2009) Consumer evaluation of apparel quality (master’s thesis).

- Swinker ME, Hines JD (2006) Understanding consumers’ perception of clothing quality: a multidimensional approach. International Journal of Consumer Studies 30(2): 218-223.

- Joung H-M (2014) Fast-fashion consumers’ post-purchase behaviours. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 42(8): 688-697.

- Walters G (2014) Why men’s shirts today fall apart after 30 washes.

- Hallstein J, Doyle K (2014) The myth of “maxxinista”: The dirty little secret behind discount and outlet stores.

- (2005) Comparison of men’s t-shirts: How do I recognize good quality?

- (2014) Decline of quality clothes: This is frugal finery.

- ASTM (2016) Annual book of ASTM standards. West Conshohocken, PA: American Society for Testing and Materials: 7.01-7.02.

- Maynard M (2004) Dress and globalization. New York, NY: Manchester United Press, USA.

- Siegle L (2011) To die for: Is fashion wearing out the world? London: Fourth Estate.

- Glock RE, Kunz GI (2005) Apparel manufacturing: Sewn product analysis (4th edn). New Jersey: Pearson, USA.

- (2015) Fast fashion garners fast growth.

- Smith R (2014) Finding the perfect t-shirt: Why is something so simple so hard to get right? The Wall Street Journal.

- Centeno A (2013) A man’s guide to undershirts: History, styles, and which to wear.

- Keiser SJ, Garner MB (2012) Beyond design: The synergy of apparel product development (3rd edn), New York: Fairchild Books, USA.

- Kadolph SJ (2010) Textiles (11th edn), New Jersey: Prentice Hall, USA.

- Mehta PV (1992) An introduction to quality control for the apparel industry. New York: ASQC Quality Press.

- Brown P, Rice J (2001) Ready-to-wear apparel analysis (3rd edn), Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, USA.

- Salfino C (2012a) The quality conundrum Quality conundrum. Cotton Incorporated Supply Chain: Insights.

- Kadolph SJ (2007) Quality assurance for textiles and apparel (2nd edn), New York: Fairchild Publications, Inc, USA.

- Stamper AA, Sharp SH, Donnell LB (1991) Evaluating apparel quality (2nd edn), New York: Fairchild, USA.

- Norum PS (2003) A comparison of apparel garment prices by national, retail, and private labels. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 21(3): 142-148.

- O’Donnell J, Kutz E (2008) Cheap clothes make for a bad long-term investment. USA Today.

- Fashiondex (2001) The apparel design and production hand book [Technical Reference]. New York, NY: The Fashiondex, Inc, USA.

- Kendall GT (2009) Fashion brand merchandising. New York: Fairchild Books, USA.

- Johnson MJ, Moore EC (2001) Apparel product development (2nd edn), New Jersey: Prentice Hall, USA.

- Lee J, Steen C (2014) Technical sourcebook for designers (2nd edn), New York: Fairchild Books, USA.

- Holmes E (2014) Fashion brands’ message for fall shoppers: Buy less, spend more. The Wall Street Journal.

- Kiplinger K (2010) Fashionistas take a hit in the wallet. Kiplinger’s Personal Finance 64(10): 15.

- Cline EL (2012) Overdressed: The shockingly high cost of cheap fashion. New York, NY: Penguin, USA.

- Gross M (1987) Consumer Saturday: Confusing clothing categories. The New York Times.

- Bain M (2016) Bigger Faster Cheaper: One chart shows how fast fashion is reshaping the global apparel industry.

- Fasanella K (2009) Apparel price point categories.

- Collier B, Epps H (1999) Textile testing and analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, USA.

- Watson MZ, Yan R-N (2013) An exploratory study of the decision processes of fast versus slow fashion consumers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 17(2): 141-159.

- Halzack S (2016) Why are sales suffering at so many women’s stores? They made bad clothes. The Washington Post.

- McKay B, McKay K (2015) The best damn guide to men’s t-shirts on the internet.

-

Elizabeth Easter, Jeanne Badgett. An Evaluation of the Quality of Mens 100% Cotton Jersey Knit White T-Shirts. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech. 5(5): 2020. JTSFT.MS.ID.000625.

-

Quality, T-shirt, Brand, Consumer, Fashion, Merchant Retailer, Pricing, Positioning

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.