Conceptual Paper

Conceptual Paper

An Alternative Approach to Sustainable New Fashion Consumption: Shopping in the Retail ‘Waste’ Economy

Lisa S McNeill, Department of Marketing, University of Otago, Fourth Floor, 60 Clyde St, PO Box 56, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand.

Received Date: September 25, 2019; Published Date: October 01, 2019

Abstract

The fashion and textile industry, at all levels, is a major contributor to social and environmental issues worldwide. Negative impacts of fashion span the entire lifecycle of a garment, from manufacture to consumer disposal, with all channel participants, including those tasked with legislature of the industry, contributing to the detrimental effects of clothing on the world. In response to this critical problem, a movement of fashion and textile producers and retailers who promote their goods as ‘ethical’ or ‘sustainable’ in production, process or human resource has emerged. Further, consumers of fashion and textile goods are questioning fast fashion’s dominance and practices and are less motivated to purchase products that recognized as ‘unsustainable’. However, despite this apparent concern regarding the industry generally, actual purchase behavior, unsustainable textile production and garment disposal continues to increase around the world. This paper thus considers the complexity of the problem from a consumer change perspective, offering a conceptualization of a consumer education model concerning fashion and textile choice in the modern world.

Keywords: Fast fashion; Conscious consumption; Retailing; Sales and marketing; Consumption ethics

Introduction

This paper takes a conceptual approach, combining current literature perspectives with findings of previous studies to develop a model of consumer change. Insights from extant theory are thus combined with secondary analysis of depth interview data collected on this topic over a five-year period. The resultant model is then critiqued in a reflexive fashion, considering the application of theory to practice. Lastly, a future direction for consumer change action is proposed, in reference to the fashion and textile industry. The core research question that directs this paper is: How can stubborn high-volume fashion consumers be educated to moderate their consumption behavior toward a more sustainable future?

Theoretical Framing

Sustainability and fashion are often seen as two contradictory terms; the former is concerned with longevity, the latter defined by increasingly short lifecycles. There are also significant public calls for consumers to reduce their consumption of well-known fastfashion brands and for the fashion industry generally to counter the massive textile waste problem the world is facing. China, USA, EU and India are the World’s top 4 global greenhouse gas emitters and they are also the World’s top 4 garment producers by volume [1]. However, the problem is not one of production and manufacturing alone. Approximately 15 percent of consumer used clothing is recycled, whereas more than 75 percent of pre-use textile is recycled by the manufacturers [2]. Global clothing production doubled from 2000 to 2014. The average person buys 60 percent more items of clothing every year and keeps them for about half as long as 15 years ago [3].

Fashion textiles can be defined as items of adornment that are culturally recognized and symbolic [4]. The acquisition of garments is thus closely linked to notions of economic, social or cultural capital [5]: ‘When I am out alone, I am much more controlled than when I am shopping with others. I guess then [buying fashion] is a social activity and therefore fun . . . Impulsive purchases have a lot to do with [my friends]’ [6]. Materialistic practices are thus a necessity of the process of identity construction and redefinition for many consumers, but particularly for young adult consumers: ‘I find that I buy clothes to look cool and to fit into whatever trend is in at that time. People judge people by what they wear and group them, so I dress to what group I want to be in’; ‘At this point in your life [youth] it is important to look good. [We] are on show . . . Everyone is judging everyone’. The marketing of clothing is therefore concerned with control over identity markers and the communication of a predetermined vision of ‘self’ to the consumer – this vision of self often one of constant change in response to fashion trends and cycles: ‘I find that I buy clothes to look cool and to fit into whatever trend is in at that time. People judge people by what they wear and group them, so I dress to what group I want to be in’ [6].

Fashion is an artefact of the extended self, and fashion items are used to develop, express and confirm identity socially [7]. This often means that large volumes of fashion products are consumed, with little conscious intention toward re-use or longevity. The very lifestyles of consumers supporting the acquisition of even more fashion-wealth: I have a very, very large number of dresses, like 21st [birthday] kind of dresses, and I don’t need them all, and every time I go shopping I will buy another one . . . you don’t want to be in the same dress in all the [social networking] photos’ [6]. When items of consumption are used to express identity, strong emotional attachments develop [8]. This attachment explains not only the significance of fashion goods in the lives of many consumers, but also highlights one of the key barriers to consumption behavior change: “I like to put effort into the way I dress, as I believe dressing well will have positive effect on how people receive me”; “I tend to purchase pieces that represent who I am and tell others about my personality” [9].

People are said to have become more aware of social responsibilities and concern for the impact that their consumption behavior will have on the world [10]. Much of this is driven by consumer notions of social categorization linked to observation and judgement of others – particularly among young consumers: ‘you couldn’t wear the same thing to class every day, or people would notice, because you are with them every day’; [It is] “very easy to compare yourself and if you feel underdressed in comparison, then I find that I actually do become quite conscious of what I am wearing [11]. Even generally understood topics, such as labor practice, don’t always influence behavior: “I’m very anti it, but there’s different levels of that labor now, and some of the people in it are happy. Like, they really wouldn’t have a job anywhere else. Well, not happy, but they’ve got to feed their families, so I guess they’re happy enough” [11]; “I mean I’ve heard of companies that have been accused of it before, Like Nike and Gap and those stores, but I don’t really think that in [my country] it reaches this far. But I guess it probably does, but [no] I don’t think it is something that influences me to be honest” [11].

Consuming fashion sustainably is a complex area, and definitions of sustainability suited to manufacture may not be suited to that of consumer use of fashion products. A definition of sustainable consumption suited to the perspective of the end consumer was suggested by Haugestad AK [12], who proposed that:

“our consumption pattern is sustainable if all world citizens can use the same amount of basic natural and environmental resources per capita as you do, without undermining the basis for future generations to maintain or improve their quality of life”

This definition highlights the critical areas of fashion consumption by end users where unsustainable practices warrant attention – that of over-consumption and disposal practices of clothing consumers.

Textile research focuses on sustainability has provided the world with novel alternatives to traditional fabrics, including plantbased textiles, plant-based leathers, recycled plastics (gathered from the ocean) and textiles designed to break down safely at disposal. However, rise in popularity of the sustainable clothing brand is contradicted by the actions of large segments of consumer in regard to the bulk of their fashion purchasing [13]: “I just feel that I need to update my clothes to get with the latest trends”; “after seeing fashion, you want to be a bit more funky and cooler with your fashion choices”; “It plays on your mind a bit and sort of frustrates you a wee bit that your current wardrobe doesn’t quite live up to that” [9].

Contributing to this gap between attitude and behavior, many consumers have limited awareness of the environmental impacts of clothing. Further, these consumers feel unable to make sustainable clothing choices, and have a lack of knowledge regarding ethical fashion: “I think that that is one of the biggest issues in sustainability, it’s that whatever decision you make, there will always be things that are acting against it. It is very difficult to evaluate information that is given, because obviously there is smoke and mirrors and lots of things in there, so how do you make decisions that are absolute?; “I feel slightly empowered [when I purchase sustainable fashion], but I realize it’s mostly a marketing gimmick. Companies realize there are neo-hippie liberals, like me, out there with pockets full of money wanting to make the ‘sustainable purchase’, so they develop general standards of sustainability to make me feel justified in purchasing their products. But I realize that any purchase I make goes against sustainability because purchase is an act of consumption and consumption is the antithesis of sustainability” [11]. Hence, the market for sustainable fashion products is small relative to other fashion categories [10].

Conceptualization

Ethically conscious fashion consumers are said to value style over trends, authenticity in fashion ethics claims, hold on to clothing longer, and are willing to pay a higher price for garments [14]. Nevertheless, research suggests that fashion consumers are trendbased, often consume trend-based garments at the lower price end of fashion and dispose of clothing products over at a rapid rate. The inextricable link between fashion and emotion encourages such behavior, despite knowledge of environment and social impact of such consumption: “I like the way that [fashion] makes you feel. It makes you feel confident if you’re up to date and things like that. It makes you feel like you fit in, and just that you look good, and you feel good” [15].

Young female consumers particularly are flexible, price conscious and aware of trends. They also discard garments rapidly. This behavior suggests potential for models of fashion exchange that re-sell, swap or share goods between users, however actual access to these models for most young female consumers is limited. Further, when consumers enter transitional or liminal life phases, such as the movement from teen to adulthood, consumption and fast discard of fashion products becomes part of the identity negotiation process: “maybe it’s just the age we’re at, or the whole [living away from home] thing. Everyone wants to like be accepted and, I don’t know, [everyone wants to be] cool?” [15].

Measures to change a consumer’s behavior can be classified as “hard” or “soft”, depending on the level of choice inherent within the system [16]. Hard measures tend to be restrictive and legislative, such as a government ban on fast fashion retail within a country. This type of measure has not, however, been considered particularly persuasive, with consumers seeking approaches to circumvent the imposed restrictions (for example, if fast fashion retail were banned in a particular country, consumers would likely still import products via overseas channels). Further, hard measures are punitive toward certain groups of consumers – in the theoretical fast fashion ban example, one can argue that the measure punishes those with limited finances.

“Soft” product usage behavior moderators take into account the personal needs and attitudes of the end user, as well as the sustainability needs of the environment and wider community, seeking to combine these in opt-in models tailored to specific subsets of consumers. These soft sustainability measures incorporate product-service systems (PSS) to facilitate and enable sharing of goods between consumers [17]. PSS allow a user to pay for the benefit of a product, without needing to own the product outright, and multiple products can be shared among multiple consumers. In the fashion and textile context, designer rental systems have long been popular to allow fashion orientated consumers of all socioeconomic profiles access to good previously considered outside of their reach.

A ‘Soft’ measure that could be applied in the fashion and textile context would be to educate consumers about how to purchase fashion more consciously – taking a more holistic perspective on what that actually means in the everyday lived experience context of the fashion consumer. If we accept that much fashion consumption occurs outside of the ‘sustainable’ (e.g. ethically produced) space, and accept that fashion consumption is often driven by emotional desire for trends, brands and the hedonic high of shopping, clear models that reduce purchase misconceptions, confusion and difficulty in choice are critical. Taking a view of conscious consumption that embraces all aspects of fashion acquisition behavior would thus propose ethical choice models that acknowledge behavior that sits outside of the standard sustainable or slow fashion sphere. This approach may also give consumers of all financial means the opportunity to construct ethical purchasing systems that work for them, in their own purchasing framework.

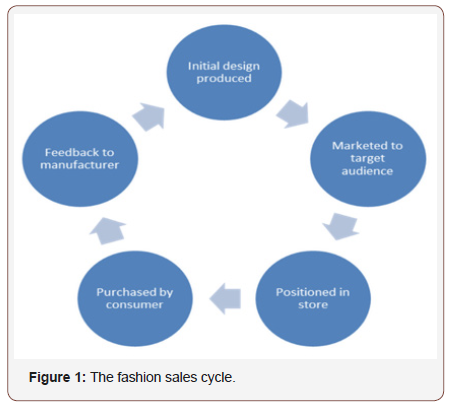

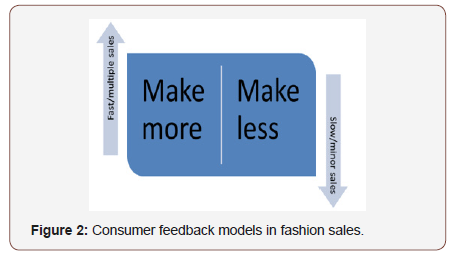

The first step in producing a workable model that deals with the unsustainable end of fashion purchasing is in helping consumers understand the fashion sales cycle, and what that means for the future of production. The critical element of the basic sales cycle in this context is the relationship between consumer purchase of current fashion goods and production of the next succession of garments (Figure 1). This component of the fashion sales cycle is represented as feedback to the retailer, and then to the manufacturer. It is a simple equation – the more that is purchased, the more that is produced; the faster it is purchased, the faster more is produced – but it is an equation that has resulted in increasingly short fashion cycles (in some fashion brands, up to 52 new product ranges per year) and still growing consumption and disposal of fashion goods worldwide (Figure 2).

From a sustainability perspective, the obvious solution to the interrupting the feedback loop is for consumers to purchase within alternative retail models, such as second hand, rental or nonmarket mediated clothing swap/lending programs. However, many young fashion consumers cite inherent issues with these alternative retail models. Unless items are specialist, such as vintage, rare or particularly unique, second hand fashion is often seen as too expensive (compared to cheap, imported, new fashion), not ‘in style’ (and the cohort has limited skills for re-making or alteration), too difficult to sort/seek (desired garment types compared to traditional retail) and standard used garment resale simply does not have an attractive image for many: “I would never take people’s second hand clothing, but if people can’t afford clothes, then they can have my old ones”; I only buy something in a second-hand shop if I really like it. Not because I know it’s good for someone or something else” [11]. Even those who exhibit positive opinions regarding second hand garment purchase are often influenced by peers to avoid this channel: “I always used to buy second-hand clothes, but my girlfriend doesn’t like it so that influences me and I don’t go to second-hand shops so much anymore” [11].

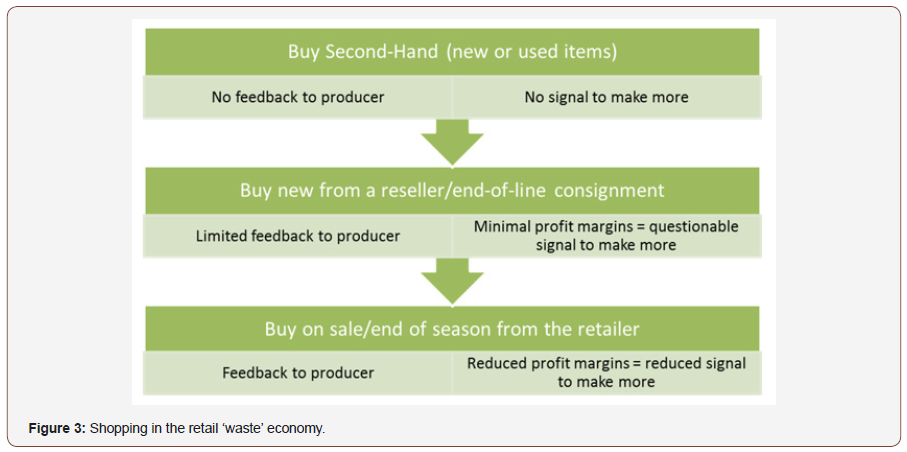

Prior studies have highlighted the disconnect between general sustainable behavior (e.g. recycling, reducing waste, making sustainable product/service choices etc.) and fashion acquisition or disposal behavior. Further, fashion sales continue to increase worldwide, at almost every level of production (from cheap, fast fashion to luxury) and at every point on the sustainable production spectrum. If some consumers are resistant to alternatives to buying new, and many of these consumers are unwilling or unable to purchase sustainably produced new fashion, a useful approach would be to educate these consumers as to how they can become more considered in their new garment choice process. This process draws on the importance of feedback in the marketing sales channel. As previously noted, positive feedback to the manufacturer or brand promotes production. The key question then is what forms negative feedback might take, that allow particular consumer groups access to desired items with less of a push toward sales growth in the channel? The following model is one approach to managing consumer choice and feedback in this sense (Figure 3).

The model presents a stepwise, tiered approach to consumption, that asks those consumers determined to buy new, non-sustainable fashion to be more conscious in the process of decision making they follow. At the first level, a consumer is challenged to seek suitable/ desirable products that are being re-sold by others. This should be the first stage of the consumption choice process. At the second level, the consumer is asked to consider the offerings of alternative retail channel providers before making a decision to buy from the retailer. At the third and final stage of the conscious choice model, the consumer is asked to limit retail purchases to items already deemed as ‘waste’ by the retailer. The model is simple; however, it is a challenging one for consumers who are conditioned to buy cheap, fast fashion as soon as they see it in store. Further, there are flaws to the model in that these garments are still part of the fast fashion retail cycle, there are still large volumes of products entering the market, and the model does not address attitudinal change toward fast fashion products. However, consumption attitudes and behaviors are many, and varied. Significant numbers of consumers are stubbornly resistant to change, and some do not see their contribution to the fashion industry as problematic. Models such as this are targeted towards particular segments of consumer, offering one pathway toward consciousness in buying behavior.

Conclusion

The consumer phase of fashion and textile lifecycles is a critical one in attempting to reduce the environmental and social burden of the garment industry worldwide. If we accept that a proportion of fashion purchases will continue, in at least the short term, to be made within the segment of the industry deemed the most unsustainable (e.g. fast fashion, designed short lifecycle products), it is vital to examine models for small aspects of behavior change that address this issue. The model for consumption within the retail waste sector proposed here is a starting point for consumer education within the stubbornly unsustainable fashion consumption segment. It is hoped that offering easy to adopt avenues for behavior change, that are not perceived to impact consumer choice as much as more stringent measures might, will be more readily adopted by this segment of the fashion population. Further, there may be ancillary benefits to this model of new garment purchasing, such as enabling access to more expensive brands that are more likely to be valued for longer and have a greater lifecycle once in the closet of the consumer. Extensions to the model would then logically address motivations to repair or care for garments, as well as motivations to re-sell, trade or gift higher values items. This may lead naturally into a focus on enabling consumers with the skills required for better garment care and textile repair or alteration, thus changing the current view of which textile skills are ‘outdated’ or ‘old-fashioned’.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- (2017) WRI CAIT Climate Data Explorer.

- (2018) The balance small business.

- (2018) Strike for the climate.

- Belk RW (1988) Possessions and the extended self. The Journal of Consumer Research 15(2): 139-168.

- Bourdieu P (1984) Distinction (Trans by Richard Nice), Routledge, London.

- McNeill LS (2014) The place of debt in establishing identity and self-worth in transitional life phases: young home leavers and credit. International Journal of Consumer Studies 38(1): 69-74.

- Either KA, Deaux K (1994) Negotiating social identity when contexts change: maintaining identification and responding to threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67(2): 243-251.

- Miles S, Cliff D, Burr V (1998) Fitting in and sticking out’: consumption, consumer meanings and the construction of young people’s identities. Journal of Youth Studies 1(1): 81-96.

- McNeill LS (2017) Fashion and women’s self-concept: a typology for self-fashioning using clothing. Journal of Fashion Marketing & Management 22(1): 82-98.

- Yan RN, Hyllegard KH, Blaesi LF (2012) Marketing eco-fashion: The influence of brand name and message explicitness. Journal of Marketing Communications 18(2): pp. 151-168.

- McNeill L, Moore R (2015) Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum- fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. International Journal of Consumer Studies 39(3): 212-222.

- Haugestad AK (2002) The Dugnad: Sustainable Development and Sustainable Consumption in Norway. 6th Nordic Conference on Environmental Social.

- Shaw D, Hogg G, Wilson E, Shui E, Hassan L (2006) Fashion Victim: The impact of Fair-Trade concerns on clothing choice. Journal of Strategic Marketing 14(4): 427-440.

- Payne AR (2013) Design, sustainability and Australian mass‐market fashion: Three case studies (Doctoral dissertation). Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane.

- McNeill L, Ventner B (2019) Identity, Self-Concept & Young Women's Engagement with Collaborative Fashion Consumption. International Journal of Consumer Studies 43(4): 368-378.

- Stopher PR (2004) Reducing road congestion: A reality check. Transport Policy 11(2): 117-131.

- Piscicelli L, Cooper T, Fisher T (2015) The role of values in collaborative consumption: Insights from a product-service system for lending and borrowing in the UK. J Clean Prod 97: 21–29.

-

Lisa S McNeill. An Alternative Approach to Sustainable New Fashion Consumption: Shopping in the Retail ‘Waste’ Economy. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech. 3(5): 2019. JTSFT.MS.ID.000575.

-

Fast fashion, Conscious consumption, Retailing, Sales and marketing, Consumption ethics

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.